The 25-year-old Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act has been repeatedly criticised for failing to stem Australia’s biodiversity decline. These national laws are meant to protect threatened species and scrutinise some developments over the damage done to ecosystems.

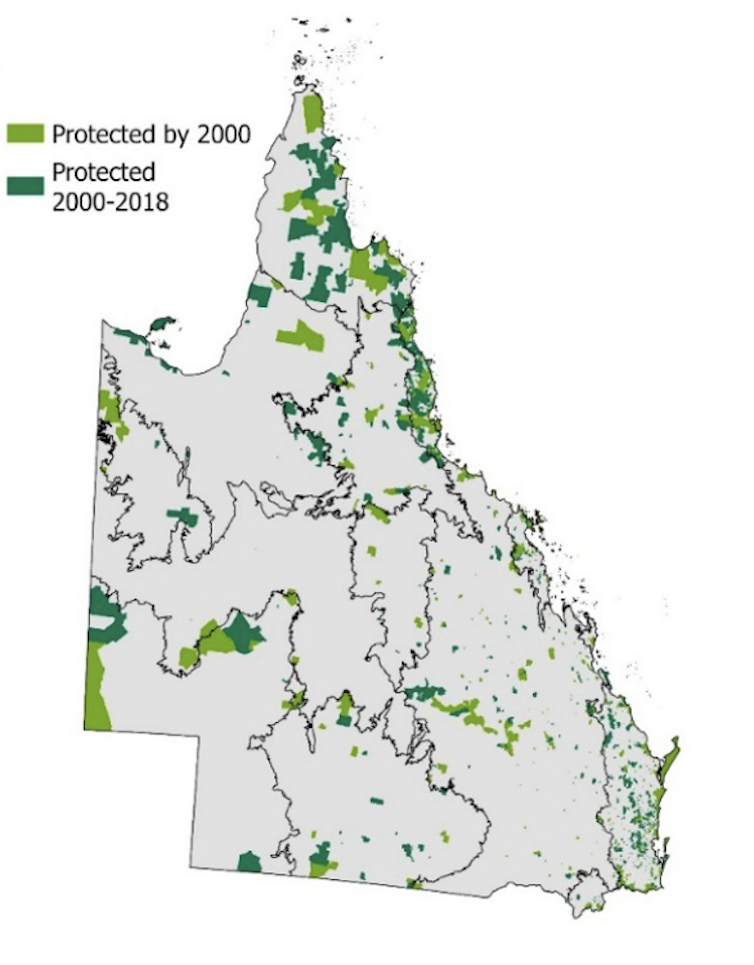

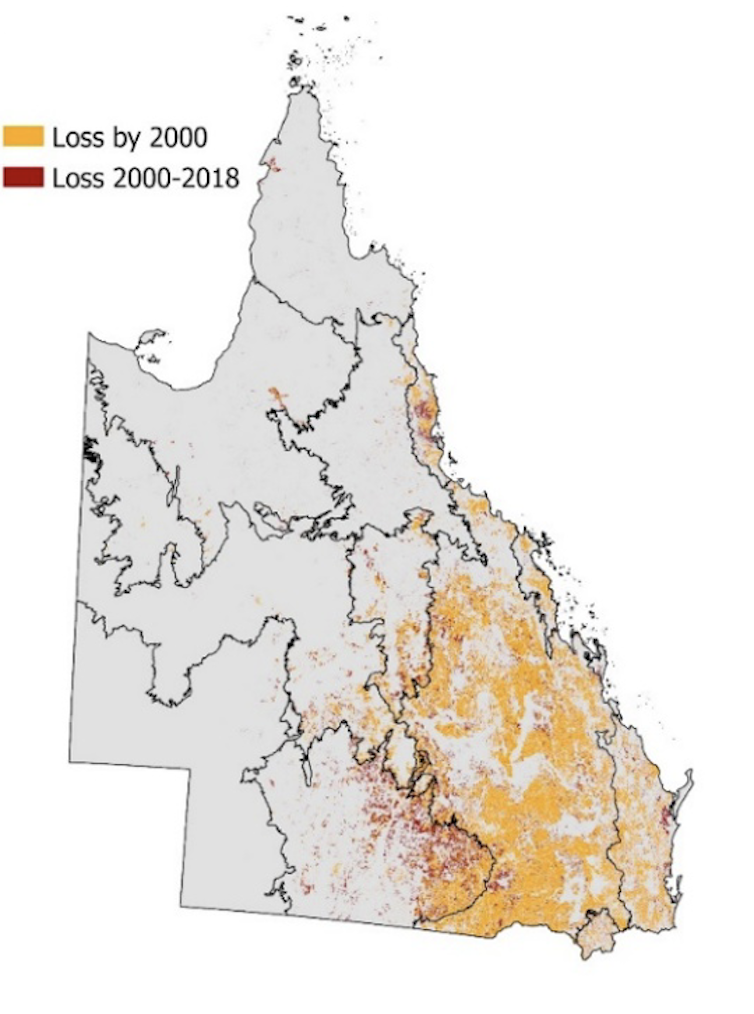

But they haven’t worked. Species have kept going extinct, land clearing in Queensland and the Northern Territory has continued at high levels, and threatened species have declined every year since 2000.

The act’s flaws were laid bare in the 2020 Samuel Review. Lead author Graeme Samuel and his technical panel also laid out a reform blueprint.

Labor promised to overhaul these laws in its first term, using this blueprint as a guide, but ran into intractable political challenges.

Today, the government has tried again, tabling a reform package in parliament that includes bills to reform environmental protection and establish a national environmental protection agency.

Environment Minister Murray Watt has pitched the reforms as a win for both the environment and for business, which would benefit from faster approvals. It remains to be seen whether the legislation will get the support it needs to pass into law.

Could these draft laws really stop the steady decline of Australia’s unique species? My assessment is that some good features are included, but signs of compromise are everywhere.

Ministerial discretion wound back, no national standards yet

A key criticism of the existing laws is the almost unfettered discretion given to the environment minister of the day. A project found likely to cause significant environmental harm by the environment department can still be given a green light by the minister.

The Samuel Review recommended this discretion be tightened up by developing National Environmental Standards to help promote the survival of threatened species.

The minister’s decision would need to be consistent with these standards unless, as the review states, there was a “rare exception, justified in the public interest”.

On these grounds, the draft laws aren’t enough. The reforms would let the minister make standards, but not require them to be developed. The standards would be statutory instruments rather than laws, and are under development, according to the government.

This is a glaring absence, given the standards were described by Samuel as the “centrepiece” of his reform proposal.

If standards are created, they will have some effect on decisions. Under the new bill, the minister must not approve an action unless satisfied the approval is “not inconsistent” with them. The same requirement would apply to a state government if a decision is delegated to them.

This seems promising. But the use of the term “satisfied” means the minister still retains more discretion than Samuel intended. Much also depends on the standards themselves.

More positively, the bill addresses the question of unacceptable impacts. For instance, if a developer wants to build a new suburb on grasslands that represent one of the last remaining tracts of habitat for a critically endangered species, this could be considered an unacceptable impact.

Under the bill, the minister must not approve a development unless satisfied it will not have unacceptable impacts. Again, the word “satisfied” makes it a subjective assessment, but the inclusion of unacceptable impacts is an improvement over the current law.

This amendment is already shaping up to be unpopular with the mining lobby, so it’s yet to be seen if it becomes law. Mining company pushback was influential in killing Labor’s reform efforts in its first term.

Finally, all of these slight improvements in discretion can be overridden if the minister deems it to be in the “national interest”, a phrase not defined in the act.

Offsets still too prominent

The existing laws have long been criticised for their overreliance on biodiversity offsets, where a development doing damage to habitat can offset this by buying or restoring equivalent habitat elsewhere.

In his review, Samuel noted offsets had become the default option, rather than a last resort. It’s far better if damage can be avoided in the first place.

Unfortunately, offsets are still front and centre. The reform bill doesn’t require project developers to explore avoiding or reducing damage before moving to offsets under the so-called mitigation hierarchy. The minister must ‘consider’ the hierarchy, but is not obliged to apply it.

The bill tabled today also introduces “restoration contributions”. These essentially allow applicants to pay money into a offset fund rather than doing it themselves. A New South Wales scheme like this has attracted controversy as the fund has amassed money that can’t be spent as there’s no suitable replacement habitat. Without proper safeguards, these contributions are likely to become a payment for doing harm.

Offsets should only be used where habitat is actually replaceable. Despite this, the reform bill doesn’t require consideration of whether offsets are feasible for a project. The minister can’t apply offsets to unacceptable impacts, but again, this is a matter of discretion.

A new national EPA with few teeth

Today’s amendments provide for the creation of a new National Environmental Protection Agency. This seems like an improvement, as there’s no federal watchdog at present.

But at this stage, its proposed powers would extend only to compliance and enforcement, not environmental approvals as originally proposed last year. Giving an independent body power to approve or refuse projects proved highly unpopular with the mining lobby. The amendments do include some strengthened compliance and enforcement powers to be administered by the EPA.

Who will sign off?

The reforms allow the federal minister to delegate environmental decision making to the relevant state or territory government. This greatly concerns environmental groups, as it would avoid the existing extra layer of federal oversight of controversial proposals.

To delegate, the minister must be satisfied the state process is not inconsistent with any national environmental standard, and meets other requirements. The minister must also be sure any actions will be approved in accordance with the planned federal standards and that they will not have unacceptable impacts.

The reforms also allow for planning at a regional scale. This allows governments to zoom out to the landscape scale and zone areas for development and conservation. If done well, regional planning can be a good way to provide certainty for developers, while stemming the trend of habitat being carved up into smaller, disconnected islands. The devil will be in the detail – any new regional plans will need to be scrutinised carefully.

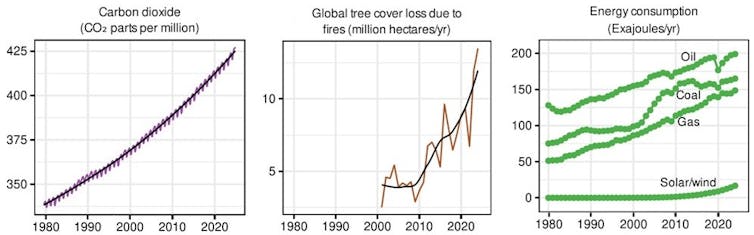

What about climate change?

Environment groups and the Greens have repeatedly called for the reforms to contain a “climate trigger”. This has been roundly rejected by two independent reviews of the act and by government.

A climate trigger would mean proposed projects would have their impact on the climate thoroughly assessed, which would increase scrutiny of coal and gas projects.

As anticipated, the amendments provide only a small concession to climate change considerations. Project developers will be required to provide an estimate of their direct emissions, but the minister doesn’t have to consider these. There’s no mention of the very large Scope 3 emissions caused by the burning of Australian coal or gas overseas.

Some progress amid many compromises

These environmental reforms are unsurprisingly a product of significant compromise due to the intensely political environment and past failures to progress reform. Even so, they face a rocky path to become law.

While the proposed reforms fail to fix some of the most problematic parts of the current laws, creating a federal EPA and legislating unacceptable impacts could lead to some improvement for the environment if other weak spots are addressed.![]()

Justine Bell-James, Professor, TC Beirne School of Law, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

%20(1).jpg?timestamp=1675893929686)

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

''

''

Shorebird Identification Booklet

Shorebird Identification Booklet