Sea surface temperatures (SSTs) in the southern hemisphere, including areas around Australia, are expected to be warmer than average during the Winter of 2025. The Bureau of Meteorology indicates that day and night temperatures are likely to be above average across Australia for this time of the year.

The BOM reports that areas off the south-west Australian coastline may be more than 3°C warmer than average.

The warm ocean temperatures surrounding Australia are a key contributor to the ongoing abnormal heat and are expected to continue until at least mid-Spring.

The additional heat in the ocean contributes to warming the air above the surface, leading to warmer winds and influencing the local environment.

The BOM states the sea surface temperatures (SSTs) in the Australian region during May 2025 were +0.62 °C above the 1991–2020 average; the warmest May on record since observations began in 1900. Since July 2024, SSTs have been the warmest or second warmest on record for each respective month.

The SST analysis for the week ending 8 June 2025 shows warmer than average waters around most of the Australian coastline, except for parts of the north. Large parts of the coastline are up to 2 °C warmer than average, with small patches off the south-west Australian coastline more than 3 °C warmer than average.

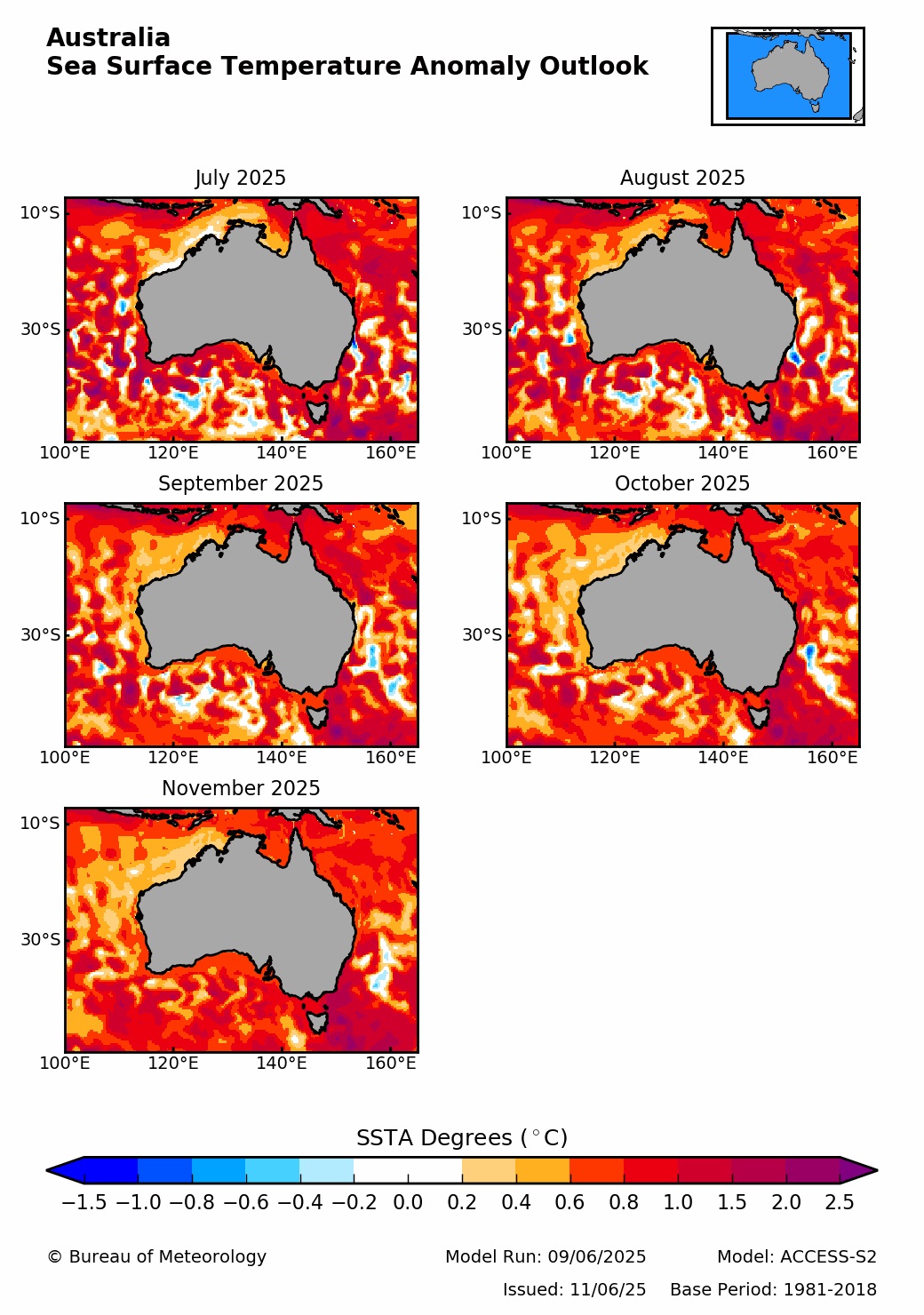

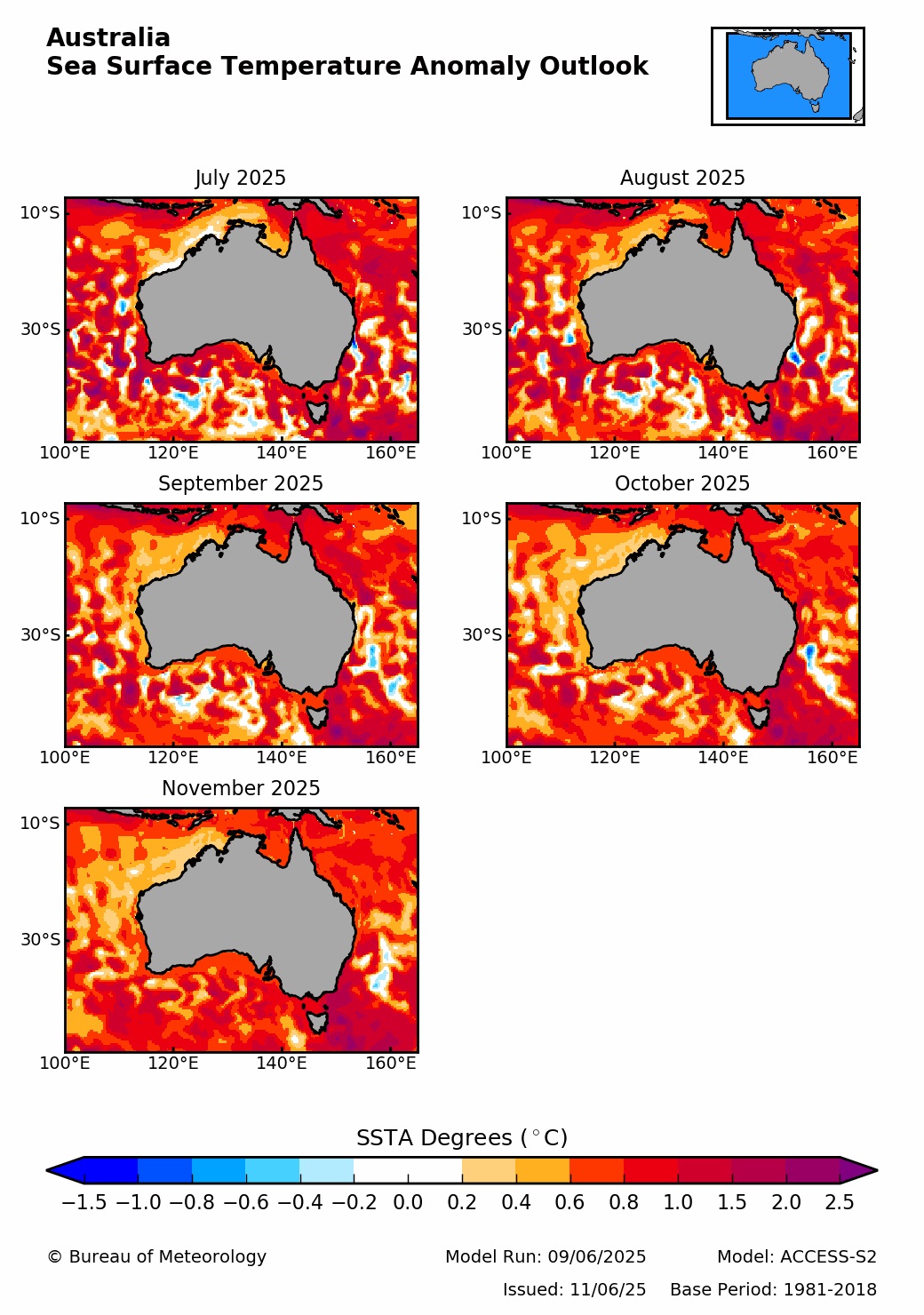

BOM: Sea surface temperature forecast maps update June 11 2025

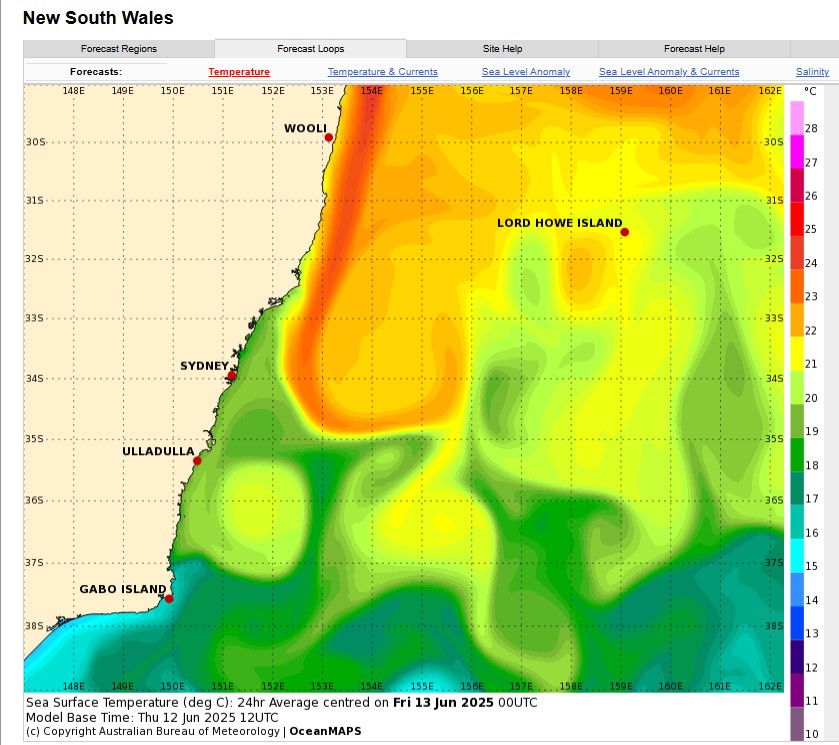

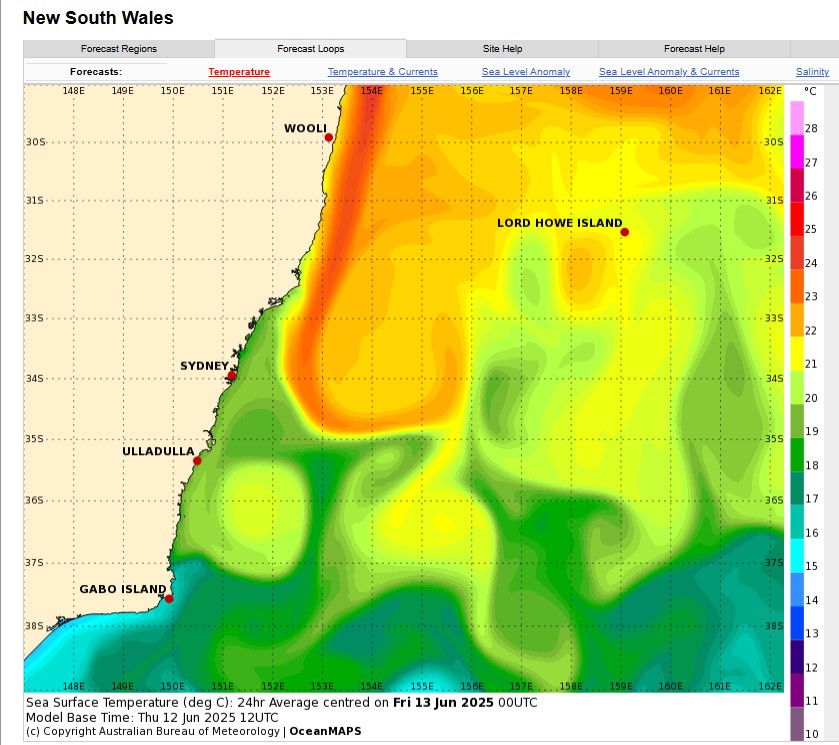

BOM: NSW sea temperature update June 12 2025:

Global SSTs remain substantially above average. Monthly averaged SSTs in 2025 have been the second warmest on record for each respective month, second only to temperatures recorded in 2024.

The CSIRO and the Australian Bureau of Meteorology State of the Climate Report 2024, released every two years, found Australia’s weather and climate has continued to change, with an increase in extreme heat events, longer fire seasons, more intense heavy rainfall, and sea level rise.

The report recorded our oceans have heated up by 1.08°C on average since 1900. In fact, Australia’s oceans are warming faster than the global average. But the oceans off south-east Australia and the Tasman Sea are a particular hotspot and are now warming at twice the global average.

The report records the average annual carbon content embedded in Australia’s fossil fuel exports between 2010 and 2019 (1,055 megatonnes) was more than double the average annual national carbon emissions over the same period (455 Mt). However, the emissions of these carbon exports are accounted in the countries where the fossil fuels are used, so Australia is heating up the planet much more than the report can record.

CSIRO Research Manager, Dr Jaci Brown, said in 2024, when the report was released, warming of the ocean has contributed to longer and more frequent marine heatwaves, with the highest average sea surface temperature on record occurring in 2022.

"The East Australian Current is shifting further south because of changes to the winds and the winds change because of changes to the surface temperature of the ocean," Dr Brown explained

"There's these feedbacks between the atmosphere and the ocean as they talk to each other. As one thing changes, it changes something in the other one which feeds back to the atmosphere."

“Increases in temperature have contributed to significant impacts on marine habitats, species and ecosystem health, such as the most recent mass coral bleaching event on the Great Barrier Reef this year,” Dr Brown said.

Impacts on species and habitats

One recurring change witnessed the past several years has been the deaths of thousands birds off our coasts through starvation - birds that rely on zooplankton for food. Zooplankton can survive in warm waters, however, they thrive in cooler waters. Marine heatwaves have been causing shifts in where and when zooplankton occur, and how large they grow.

See: Shearwaters washing up on local beaches for third year in a row: Mass mortalities of Starving Birds attributed to Australia's Lose-Lose Policy on the Australian Environment - October 2024

Another is local seagrasses - the nurseries for marine life in estuaries.

On March 27 2025 the NSW Marine Estate reported on how they will respond to these rising temperatures.

'Fisheries Scientists have explored this question for the seagrass, Zostera muelleri (also known as eelgrass), common in estuaries from Tweed Heads on the north coast all the way down to Eden in southern NSW.' the release states

'The Fisheries team from the Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development (DPIRD) tested the effects on eelgrass of water temperature elevated by 3 degrees C.'

'Surprisingly, the study found no consistent change in the density of seagrass, its size, or growth rate, despite the warmer water.

Instead, seasonal changes, sediment characteristics (the amount of organic matter present) and shading from dense leaves had far greater effects on seagrass growth than warmer water.

These encouraging results suggest that eelgrass on the central NSW coast can tolerate the warming expected by 2090 under future climate models.

'More work is needed to test whether eelgrass might be affected by increasing water temperatures in northern NSW, where this species is getting closer to its upper temperature limit.'

The research has also highlighted the importance of considering other factors that can influence seagrass growth when testing for the impacts of future climate change.' NSW Marine Estate said

You can read the full report, Sediment Properties and Seagrass Density Influence the Morphological Plasticity of Seagrass Zostera muelleri More Than Elevated Temperatures, as published in Estuaries and Coasts Journal.

In Pittwater, Posidonia australisis often fringed by the seagrass species Zostera muelleri.

Zostera muelleri is a perennial species, meaning populations of it endure year round. They are mostly found in places such as littoral or sublittoral sand flats, sheltered coastal embayments, soft, muddy, sandy areas near a reef, estuaries, shallow bays, and in intertidal shoals.

Eelgrass (zostera muelleri) can be found in estuaries from Tweed Heads on the NSW north coast down to Eden in the south, including Pittwater. Photo: Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development

Seagrasses are flowering species, but they can reproduce both sexually and asexually. Reproducing sexually increases genetic variation, which can enhance a plant's ability to adapt to a changing environment, but asexual reproduction requires less effort and is what Z. muelleri typically uses to maintain its population.

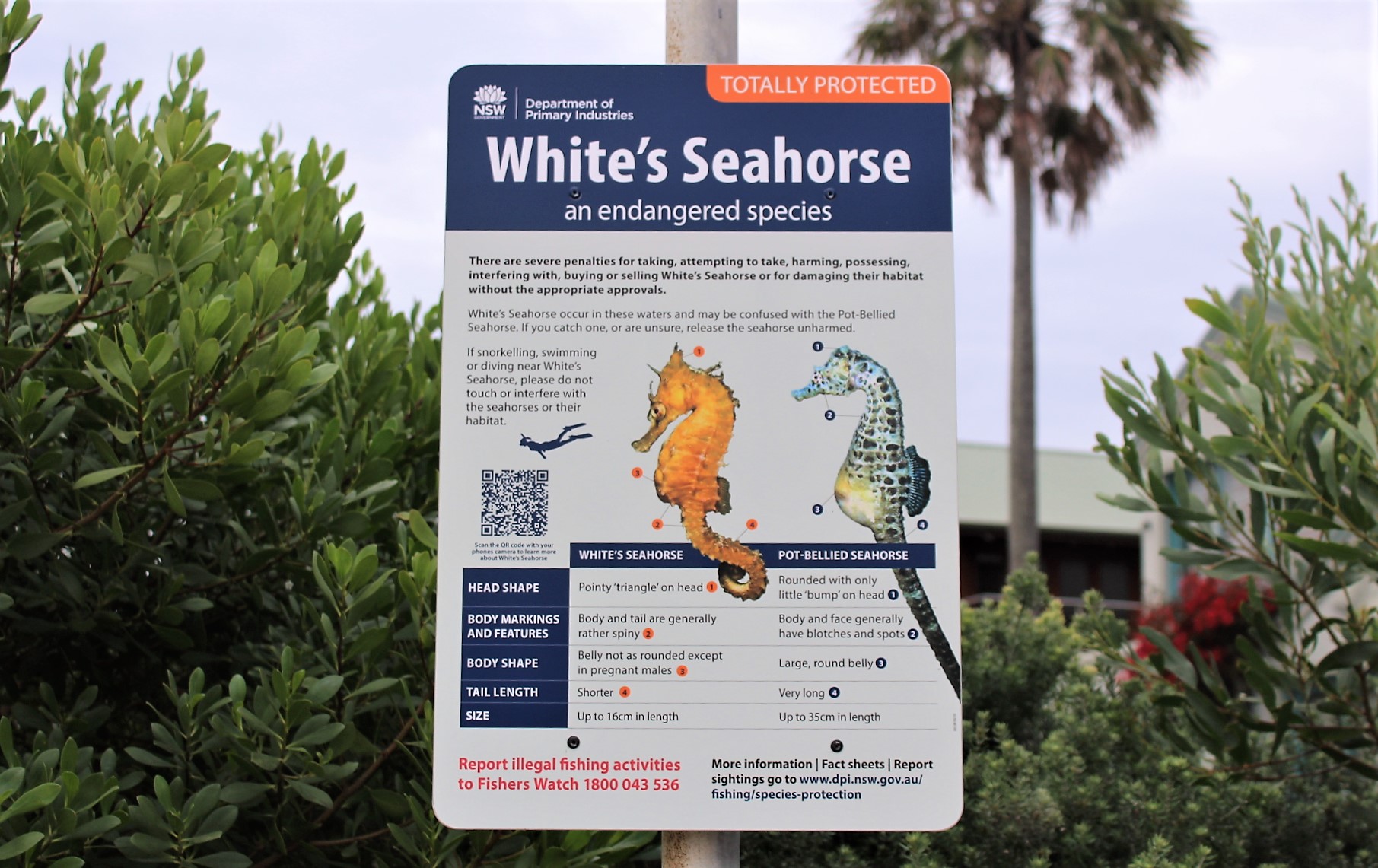

This species, and Posidonia australis, form an essential nursery habitat for various marine species, from our local seahorses and the Barrenjoey to Narrabeen Weedy Seadragons to commercially important species such as snapper and blue swimmer crabs.

See: Study shows what stresses Pittwater's seagrass meadows (and the fish that love this estuary habitat) + Jetty design review to protect seagrass and Weedy Seadragons Citizen Scientist Project Needs More Eyes On The Seas, Sands + Shores: The SeadragonSearch Project

Citizen scientists uncover climate shifts in marine species

On June 3 2025 the NSW Marine Estate stated a decade of citizen science observations has revealed shifts in marine life along Australia’s coast - highlighting the invaluable contribution of everyday ocean users in tracking these striking changes.

Divers, snorkellers and fishers reported observations of more than 200 marine species between 2013 and 2022, using platforms like Redmap Australia, iNaturalist and Reef Life Survey.

Marine Estate Management Strategy (MEMS) scientists, Drs Curtis Champion, Tom Davis and Melinda Coleman, are among a national group of researchers who have analysed that data.

Their research paper, ‘Continental-Scale Assessment of Climate-Driven Marine Species Range Extensions Using a Decade of Citizen Science Data,’ shows that nearly 40% of the 200 marine species investigated were spotted beyond their historical range limits.

''Warming oceans are acting as an invisible conveyor belt, causing species to move so they can keep within their preferred temperature ranges. Some species had shifted more than 1,000 kilometres beyond their historical distribution limits.

''The findings demonstrate the unique value of citizen science in filling critical knowledge gaps, with more than 90% of the range extensions reported in the study, not previously documented in traditional scientific literature.''

As ocean ecosystems respond to changing environmental conditions, everyday observations made by ordinary people are proving extremely valuable in detecting the early signals of change.''

This MEMS research project has also created a strong new framework to assess how confidant we can be about reported shifts in the ranges of various species. It’s hoped the framework will guide future studies on species movement in other parts of the world.'' NSW Marine Estate stated

Each summer, tropical juvenile fish, carried by the East Australian Current appear along the New South Wales coast. Now, these tropical recruits are being spotted much further south than previously reported, for example the Bluespine Unicornfish (Naso unicornis) near Narooma, has been seen about 340 km south of its previously known range limit. (Photo: A Green)

Ocean Warming Good for Tourism - unless the Ocean Burns everything in it

On January 1 2025 the NSW Marine Estate released news headed 'Ocean warming increases chances of spotting manta rays and zebra sharks in NSW - and that’s good news for tourism'

The release went on to state:

''Climate change may be giving a surprising boost to the NSW dive tourism industry, with new research predicting manta rays and zebra sharks could spend up to 4 months longer at popular dive sites on the central NSW coast over coming decades.''

''The study published in the journal Marine & Freshwater Research highlights how warming ocean temperatures are expected to extend the seasonal migrations of these iconic species and it could be good news for the dive and snorkel tourism sector where manta rays and zebra sharks are a powerful drawcard.

Tourism is already the largest industry in the NSW marine estate, contributing an estimated A$4.3 billion to this sector during the 2021–22 period according to Deloitte’s 2023 report: ‘NSW marine estate economic contribution and market insights’.

In NSW dive and snorkel tourism is an important player in the tourism sector as more people flock to coastal areas for immersive marine experiences such as snorkelling, scuba-diving and dolphin and whale watching.''

“Our research identified that the timing of manta ray and zebra shark seasonal migrations along the NSW central coast, is likely to be extended by ocean warming,” explained Research Scientist, Dr Tom Davis, from the Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development.

Longer migration seasons could generate increased commercial opportunities for dive tourism businesses, particularly for operators in the central coast region that take customers out for encounters with manta rays and zebra sharks.

And it’s not just speculation, “The intense social media interest generated by a recent sighting of a manta ray off Manly, Sydney highlights the importance that these findings will have for NSW dive tourism operators and the public,” Dr Davis observed.

Screenshot of Manta Ray post on Instagram

Harmless Zebra sharks are not the only shark species lingering in waters they would once have left by now.

In March of this year the news service reported Bull sharks, which usually leave our waters once they drop below 19C and head north, ae also staying in the warm waters off our coasts.

See: It's a 'Bit Sharky' out there: 5 Tagged Bull Sharks Pinged at North Narrabeen on Same Day - Bull Shark spotted at Bayview

And of course, apart from the projected rise in sea levels this also signals must be occurring as ice melts over the planets polar caps, the increase in ocean temperatures leading to an increase in tourism dollars won't last long if what is still occurring a little further south persists - and spreads - as is forecast for this Winter, and Spring:

![]()