March 24 - 30, 2013: Issue 103

Australian Grey Butcher Bird

A pair of Grey Butcher Birds were harassing a small young possum in our backyard on Thursday afternoon. Their songs of alarm, and perching in two trees around the possum, indicates the tree climbing egg eating possum was considered a threat to their nearby nest and any eggs it may contain. A Pied Currawong, called in by the noise, perched in a taller tree beside them, watching the show. The breeding season of Grey Butcher birds in commences in July and continues through to January so these may have simply been warning the possum from going near new young. Nests are built in forks of trees, usually at least 5 metres above the ground and is a bowl shaped construction made from twigs.

A pair of Grey Butcher Birds were harassing a small young possum in our backyard on Thursday afternoon. Their songs of alarm, and perching in two trees around the possum, indicates the tree climbing egg eating possum was considered a threat to their nearby nest and any eggs it may contain. A Pied Currawong, called in by the noise, perched in a taller tree beside them, watching the show. The breeding season of Grey Butcher birds in commences in July and continues through to January so these may have simply been warning the possum from going near new young. Nests are built in forks of trees, usually at least 5 metres above the ground and is a bowl shaped construction made from twigs.

When not warning off potential predators these birds are renowned for their beautiful warbling song. Some people have even captured them imitating other bird’s song of their habitats. Sociable, unafraid of humans, or at least accustomed to us smiling at them, this pair frequent our trees on a daily basis and have for years now.

The Grey Butcherbird (Cracticus torquatus) is a widely distributed species endemic to Australia and occurs in every state. It has a characteristic ‘rollicking’ birdsong. It appears to be adapting well to city living, and can be encountered in the suburbs of many Australian cities including Sydney. The Grey Butcherbird preys on small vertebrates including other birds and their name stems from a habit of spiking their food onto small twigs from which to eat it; kind of like a larder for birds l;ikened to traditional butcher's shops. Other birds in the same family include the Australian Magpie, the Currawongs, Woodswallows and other members of the Butcherbird genus Cracticus. This is perhaps why you see them quite happy in each other’s company and some have heard the butcher bird imitating their songs.

They have a black crown and face and a grey back, with a thin white collar. Their wings are grey, with large areas of white and their underparts are white. Their legs and claws are also grey. The grey and black bill is large, with a small hook at the tip of the upper bill which is not always obvious so that they are sometimes mistaken for small kingfishers. Dark brown eyes blink brightly at you. Both sexes are similar in plumage, but the females are slightly smaller than the males. Young Grey Butcherbirds resemble adults, but have black areas replaced with olive-brown and a buff wash on the white areas.

The Butcherbird was first described by the ornithologist John Gould in 1837 as Vanga nigrogularis, the type specimen collected near Sydney. It is one of six (or seven) members of the genus Cracticus known as butcherbirds. Within the genus, it is most closely related to the Tagula and Hooded Butcherbird. The three form a monophyletic group within the genus, having diverged from ancestors of the Grey Butcherbird around five million years ago.

Many Australian composers have been inspired by and written music incorporating the songs of Butcherbirds, including Henry Tate, David Lumsdaine (who described it as "a virtuoso of composition and improvisation"), and John Williamson. In the dance 'Birdsong' by Siobhan Davies, the main central solo was accompanied by the call of an Australian Pied Butcher bird and this same sound provided great inspiration to much of the dance, including the improvisational aspects.

MY NATIVES AND I. No. 28 : Friends in the Wilderness.

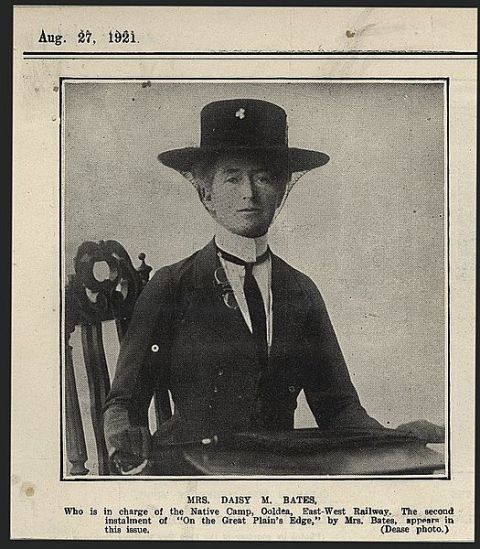

By DAISY M. BATES.

During her years at Ooldea Mrs. Daisy Bates, C.B.E., cultivated friendships not only among the aborigines but ' with the numerous birds and reptiles who soon learnt that the precincts of her tent were sanctuary. This chapter of her memoirs relates these and other experiences.

GIVEN in the wilderness of Ooldea I could yet gather wealth. to my mind, find solace in the solitude. Those who have passed the siding in the west-bound express know all there is to know — four little boxes of fettlers' huts in an arid monotony of sandhills and low scrub on the rim of the desolate plain, yet not so desolate, for I found my recompense in Nature, who smiles on me always. I might be solitary, but I was never lonely. The breakwind that enclosed my garden of sand was a veritable sanctuary of wild life. The birds and the quaint little borrowing creatures were all my friends. They, too, came to Kabbarli. I invariably rose just at sunrise, when the days are at their most glorious, and the whole world is full of beauty and music and dreaming, waking from its’ slumbers under the mists. I made my toilet to a chorus of impatient twittering. It was a fastidious toilet, for throughout my life I have adhered to the simple but exact dictates of fashion as I left it, when Victoria was queen —a neat white blouse, stiff collar and ribbon tie, a dark skirt and coat, stout and serviceable, trim shoes and neat black stockings, a sailor hat and a fly-veil, and, for my excursions to the camps, always a dust coat and a sunshade. Not until my person was in meticulous order would I emerge from my tent, dressed for the day.- My first greeting was for the birds. In myriads they came to the water vessels ranged about the camp, ready for the showers that never came and daily replenished from my water-cart. All through the 14 hours of stark daylight there were visitors to my crumb-ground, for which I saved every morsel. To my 120 native dialects, I now added the language of the birds. I welcomed them in their own sweet accents, and knew them always by the aboriginal names that in many instances are a triumph of onomatapola(from Greek; ‘name I make’), infinitely more delightful than the stilted English or the sonorous Latin of the ornithologists. With a flash of bright wings and an excited chattering they were all about me. Melga I loved above all. These little spotted and chestnut-backed ground thrushes became tame as chickens, and would walk sedately through my tent as I sat reading and writing and preen themselves in the sunny doorway until Jaggal, the bicycle lizard, came along. Miril-yiril-yiri, the blue-backed, black backed and white-backed wren, and Minning-minning, his wife, were other cherished friends. Three separate wren families lived with me in perfect harmony, and allowed me to feed the babies with white ants and other writhing morsels. Nyiri-nyiri the finches came in hundreds, drinking four kerosene tins full on a hot day, and taking shelter beneath my stretcher. Jindirr-jindirr, the wagtail, and I sang duets together. Burnburn-boolala, the Central Australian bellbird, was a gifted ventriloquist. He could stand on the top rung of my ladder observatory, and pretend to be miles away. Juln-juin, the babbler, was insulting. 'Yaa! seel Yaat seel' he would call in derision, then fall into a recital of cheap slander. Koora, the magpie, with itsliquid throaty warble of extraordinary beauty, Beelarl,. the pied bell-magpie, with his double note, and Koolardi the butcherbird, ringing the mellow changes, set mea task in musical exercises, while Gilgilga, the love-birds, and baadl-baadl, allthe smaller varieties of many coloured parrots, furled then gay wings on the'boggada' mulga above me and made cave-shelters from the heat in the shaded sands. Geergin and other hawks I discouraged; they were a menace to the little birds, and I was not too friendly to Kogga-longo, the white cockatoo. Kalli-jirr-jirr, the black-breasted plover, lays four speckled eggs in a small shallow place' on the Plain with no cover —the speckles are its protection in that mottled limestone— but the fussiness of Kalli-jirr-jirr drew the attention of hawk and butcher-bird, and she would appear at my tent-flap with a shriek, 'Come and save my eggs!' Weeloo, the curlew, had more than one group totem all to himself throughout Central Australia, but, saddened by his weight of legends, he was ever mournful, and there was that about the hard cold eye of Rool, the sacred kingfisher, that is fatal to the natives. A lone pilgrim, he wanders where he will, and is the Bird of Death. Birds have memories, quite apart from their instinct. Koolardi, Burn-burn, and all those others whom I mimicked would return the following season, and repeat their challenge. It is one of life's gayest surprises to be greeted by an old acquaintance among the wild birds, with a familiar hail and a flick of the tail after a long absence. MY NATIVES AND I. (1936, April 15). The West Australian(Perth, WA : 1879 - 1954), p. 21. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article25140902

GIVEN in the wilderness of Ooldea I could yet gather wealth. to my mind, find solace in the solitude. Those who have passed the siding in the west-bound express know all there is to know — four little boxes of fettlers' huts in an arid monotony of sandhills and low scrub on the rim of the desolate plain, yet not so desolate, for I found my recompense in Nature, who smiles on me always. I might be solitary, but I was never lonely. The breakwind that enclosed my garden of sand was a veritable sanctuary of wild life. The birds and the quaint little borrowing creatures were all my friends. They, too, came to Kabbarli. I invariably rose just at sunrise, when the days are at their most glorious, and the whole world is full of beauty and music and dreaming, waking from its’ slumbers under the mists. I made my toilet to a chorus of impatient twittering. It was a fastidious toilet, for throughout my life I have adhered to the simple but exact dictates of fashion as I left it, when Victoria was queen —a neat white blouse, stiff collar and ribbon tie, a dark skirt and coat, stout and serviceable, trim shoes and neat black stockings, a sailor hat and a fly-veil, and, for my excursions to the camps, always a dust coat and a sunshade. Not until my person was in meticulous order would I emerge from my tent, dressed for the day.- My first greeting was for the birds. In myriads they came to the water vessels ranged about the camp, ready for the showers that never came and daily replenished from my water-cart. All through the 14 hours of stark daylight there were visitors to my crumb-ground, for which I saved every morsel. To my 120 native dialects, I now added the language of the birds. I welcomed them in their own sweet accents, and knew them always by the aboriginal names that in many instances are a triumph of onomatapola(from Greek; ‘name I make’), infinitely more delightful than the stilted English or the sonorous Latin of the ornithologists. With a flash of bright wings and an excited chattering they were all about me. Melga I loved above all. These little spotted and chestnut-backed ground thrushes became tame as chickens, and would walk sedately through my tent as I sat reading and writing and preen themselves in the sunny doorway until Jaggal, the bicycle lizard, came along. Miril-yiril-yiri, the blue-backed, black backed and white-backed wren, and Minning-minning, his wife, were other cherished friends. Three separate wren families lived with me in perfect harmony, and allowed me to feed the babies with white ants and other writhing morsels. Nyiri-nyiri the finches came in hundreds, drinking four kerosene tins full on a hot day, and taking shelter beneath my stretcher. Jindirr-jindirr, the wagtail, and I sang duets together. Burnburn-boolala, the Central Australian bellbird, was a gifted ventriloquist. He could stand on the top rung of my ladder observatory, and pretend to be miles away. Juln-juin, the babbler, was insulting. 'Yaa! seel Yaat seel' he would call in derision, then fall into a recital of cheap slander. Koora, the magpie, with itsliquid throaty warble of extraordinary beauty, Beelarl,. the pied bell-magpie, with his double note, and Koolardi the butcherbird, ringing the mellow changes, set mea task in musical exercises, while Gilgilga, the love-birds, and baadl-baadl, allthe smaller varieties of many coloured parrots, furled then gay wings on the'boggada' mulga above me and made cave-shelters from the heat in the shaded sands. Geergin and other hawks I discouraged; they were a menace to the little birds, and I was not too friendly to Kogga-longo, the white cockatoo. Kalli-jirr-jirr, the black-breasted plover, lays four speckled eggs in a small shallow place' on the Plain with no cover —the speckles are its protection in that mottled limestone— but the fussiness of Kalli-jirr-jirr drew the attention of hawk and butcher-bird, and she would appear at my tent-flap with a shriek, 'Come and save my eggs!' Weeloo, the curlew, had more than one group totem all to himself throughout Central Australia, but, saddened by his weight of legends, he was ever mournful, and there was that about the hard cold eye of Rool, the sacred kingfisher, that is fatal to the natives. A lone pilgrim, he wanders where he will, and is the Bird of Death. Birds have memories, quite apart from their instinct. Koolardi, Burn-burn, and all those others whom I mimicked would return the following season, and repeat their challenge. It is one of life's gayest surprises to be greeted by an old acquaintance among the wild birds, with a familiar hail and a flick of the tail after a long absence. MY NATIVES AND I. (1936, April 15). The West Australian(Perth, WA : 1879 - 1954), p. 21. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article25140902

Daisy May Bates, CBE (16 October 1859 – 18 April 1951) was an Irish Australian journalist, welfare worker and lifelong student of Australian Aboriginal culture and society. She was known among our indigenous people as 'Kabbarli' (grandmother).

References:

Daisy Bates (Australia). (2013, March 11). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Daisy_Bates_(Australia)&oldid=543500100

Grey Butcherbird. (2013, March 14). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Grey_Butcherbird&oldid=544133537

Pied Bucther Bird imitating other birds, filmed at Seal Rocks by Noddy107 at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KfaplSc5ieM

Schodde, R. & Mason, I.J. (1999). The Directory of Australian Birds : Passerines. A Taxonomic and Zoogeographic Atlas of the Biodiversity of Birds in Australia and its Territories. Collingwood, Australia: CSIRO Publishing.

Photos by A J Guesdon, March 2013.