May 21 - 27 2023: Issue 584

Ringtail Posse 4 - May 2023

Andrew Gregory: Powerful Owl, Marita Macrae: Pale-Lipped Or Gully Shadeskink, Jools Farrell: Whales & Seals, Nicole Romain: Yellow-Tailed Black Cockatoo

Definition from

Ringtail: from the 'Common Ringtail Possum' which is not so common anymore in urban areas. The Common Ringtail Possum is found along the entire eastern part of Australia and south west Western Australia. They are also found throughout Tasmania. The western ringtail possum is a threatened species under State and Commonwealth legislation. In Western Australia the species is listed as Critically Endangered fauna under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016.+

Posse: noun. 1 : a large group often with a common interest 2 : a body of persons summoned by a sheriff to assist in preserving the public peace usually in an emergency 3 : a group of people temporarily organised to make a search (as for a lost child) 4 : one's attendants or associates.

In recent approved DA’s Council is listing as a requirement of consent in Assessment reports to look after the other residents of this area, the wildlife. On blocks where people wish to remove large amounts of trees that are clearly homes for local fauna a wildlife expert must assess these prior to any removal taking place, nesting boxes are required to be installed afterward and Ecologists must be on site during their removal. Other recent examples and instances are:

Bandicoot/Penguin (Avalon)

Long-nosed Bandicoots & Little Penguins – Best Practices for Residents

Residents are encouraged to follow a number of Best Practices to assist with the protection and management of the endangered populations of Long-nosed Bandicoots and Little Penguins:

Long-nosed Bandicoots, Little Penguins and other native animals should never be fed as it may cause them nutritional problems, hardship if supplementary feeding is stopped, and it may increase predation.

Feral cats or foxes should never be fed or food left out where they can access it, such as rubbish bins without lids or pet food bowls, as these animals present a significant threat to Longnosed Bandicoots, Little Penguins and other wildlife.

The use of insecticides, fertilisers, poisons and/or baits should be avoided on the property.

Garden insects will be kept in low numbers if Long-nosed Bandicoots are present.

When the North Head Long-nosed Bandicoot Recovery Plan is released it should be implemented where relevant.

Dead Long-nosed Bandicoots or Little Penguins should be reported by phoning Manly Council on 9976 1500 or Department of Environment and Conservation on 9960 6266.

Please drive carefully as vehicle related injuries and deaths of Long-nosed Bandicoots and Little Penguins have occurred in the area. Care should also be taken at night in the drive way when moving cars as bandicoots will seek shelter beneath vehicles.

Cat/s and or dog/s that currently live on the property should be kept indoors at night to avoid disturbance/death of native animals. Ideally, when the current cat/s and/or dog/s that live on the property no longer reside on the property it is recommended that they not be replaced by new dogs or cats.

Report all sightings of feral rabbits, feral or stray cats and/or foxes to N B Council.

And;

Dead or Injured Wildlife (Palm Beach)

If construction activity associated with this development results in injury or death of a native mammal, bird, reptile or amphibian, a registered wildlife rescue and rehabilitation organisation must be contacted for advice.Protection of Habitat Features

All natural landscape features, including any rock outcrops, native vegetation and/or watercourses, are to remain undisturbed during the construction works, except where affected by necessary works detailed on approved plans.

Reason: To protect wildlife habitat.

The Reason given in all instances is: To protect native wildlife.

This follows on from the 2022 Local Government NSW Conference where a Motion was passed - That Local Government NSW lobby the NSW Government to:

- In conjunction with industry associations, introduce enforceable standards for the preparation of flora and fauna management plans.

- Consider Codes of Practice and Guidelines for handling native wildlife and other best practice and animal welfare laws in development of the standards.

- Consult with Councils, National Parks and Wildlife Service, Ecological Consultants Association of NSW, wildlife rescue organisations and other relevant agencies in the preparation of standards.

Such a standard should include requirements for:

- Pre-clearance surveys to be carried out to establish which species are present on the site, including identification of any threatened and native species.

- The identification of suitable nearby areas where wildlife could possibly be relocated.

- The provision of possum, glider and bat boxes sufficiently in advance of vegetation clearing to allow wildlife time to discover the boxes and become familiar with them.

- Compliance with the NSW Code of Practice for Injured, Sick and Orphaned Protected Fauna and the licencing requirements contained in the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016.

- Best practice for wildlife handling and care (including contact with local wildlife rescue groups).

- Reporting of injured or killed fauna to the NSW Department of Planning, Industry and Environment to enable the data to be used in statewide biodiversity monitoring programs.

The premise of this is that mandatory pre-clearance surveys to establish what wildlife lives there before works commence, and to document this in a formal way, should be required on any site that has vegetation and for which a DA has been approved. The experience is that often vegetation is removed before an application is submitted, often leaving wildlife with no home. Wildlife then ends up on roads dead or dies after being displaced/evicted.

One wildlife carer cited a recent Pittwater case of a powerful owl pair site that had had vegetation removed to make the development more likely to proceed – the nest and two babies were destroyed.

‘It’s hard to prove wildlife is/was present after the clearing as they aren’t there.’

‘Once trees and vegetation are removed the problem is where do these animals go?’

Powerful Owls are also not so common anymore in urban areas.

However it's clear human residents of this LGA have a deep and abiding love for and connection to these other furry, scaled, finned and feathered beings. We listen for them during the night, happy when we hear their footsteps scampering across our rooves or their soft hoots across the valleys.

Human residents are distressed when they find injured wildlife or witness wildlife being attacked.

Data kept by the NSW Environment Department, although only listing incidents from June 2013 to June 30 2021, shows that 33,391 wildlife animals have been rescued in our area between June 2013 and June 30 2021 and just 8, 812 released again. Of these 42 were threatened species.

''This study draws on 469,553 rescues reported over six years by wildlife rehabilitators for 688 species of bird, reptile, and mammal from New South Wales, Australia.... Of the 364,461 rescues for which the fate of an animal was known, 92% fell within two categories: ‘dead’, ‘died or euthanised’ (54.8% of rescues with known fate) and animals that recovered and were subsequently released (37.1% of rescues with known fate).''In total, there were 872,087 records reported during the six-year (2013–14 to 2018–19) study period. Just over 97% of these came from three animal groups–birds, mammals, and reptiles. Of the total number of records, 402,534, (46%) were excluded from the descriptive analysis because they: a) did not contain any information about the animal, or the animal’s identification was ambiguous and could not be placed within a group (e.g. an ‘unidentified animal’); b) contained only sightings of animals and were not attended to in some way by a wildlife rehabilitator; c) were records of amphibians (373 records) or non-vertebrate fauna (e.g. spiders, insects, etc.); d) were non-avian marine vertebrates such as whales, seals, sharks, rays, fish etc; e) were reported as floating, drowned, or washed up animals (deemed an ambiguous cause for rescue, n = 48); f) contained both an ‘unknown’ cause for rescue and an ‘unknown’ fate; or f) were an introduced or spurious species (e.g. extinct, or out of known range). These exclusions resulted in a dataset for descriptive analysis of 469,553 records i.e. 54% of the initially reported amount.''

Data to 30 June 2021 lists of the 5, 235 animals rescued during that 2020 to 2021 period just 1,573 were released. Across NSW during that same year a total 120, 927 animals were rescued and just 28, 805 released - 5, 122 of these were were threatened species (104 kinds) of which just 1,180 were released.

These figures and data do not take into account all the wildlife found deceased beside or on roads or elsewhere.

Many people state we are the generation witnessing the extinction of urban wildlife. There has been generation after generation of humans living alongside and with wildlife, until this one.

It's not just the Pittwater koalas that have gone, other species, like the ringtail possum or long-nosed bandicoot are disappearing, along with their joyful snuffles and squeaks, from our urban backyards and the trees that tower over them.

There is a growing silence at night for those species that forage for food then - possums, wallabies, owls. The same is occurring for those that are active during daylight.

Although many point to the impacts of cat and dog attacks due to irresponsible owner, there is also what is termed the 'inconvenient possum' in a roof or garden shed, because its home tree has been cut down. These are caught by those hired, some of whom have little knowledge or scruples, and release them into areas out of their home range - a death sentence for that possum as this species is territorial, along with requiring certain food trees in order to eat, to survive.

There is predation by other introduced species - readers regularly send in photos and videos of foxes roaming and killing at night.

There are roadkill black spots, places where wallabies or turtles or possums used to cross the area where a road has been cut through and a speed limit that means death for wildlife. There are no 'speed humps' in place, and no plan at a local, state or federal government level to istall these. Residents and wildlife rescuers have reported some drivers 'aiming straight for' a stricken animal.

There is the razing of blocks of land for development prior to any required assessment of the environment taking place to circumvent those requirements so a report can state 'nothing present'. There is nothing present because its habitat has been cleared or the wildlife killed by these actions.

Our local wildlife carers are getting exhausted, state there have been so many, too many so far this summer - they are increasingly heartbroken with all the babies they lose, they cry every day, and then pick themselves up and get on with trying to save the next critter, and the next.

Wildlife carers are all volunteers - they do the rescues, sometimes horrific rescues, run to and fro from the great local vets who help out trying to save them, they gather or pay for the food, for the milk, for the petrol, for the electricity to keep bubs warm. There are no grants or funding for Australia's wildlife carers - they have to raise funds through running events, raising awareness, collecting cans for a 10 cent return.

Similarly we are not in denial that all our local wildlife feels and thinks - they cry when their babies are killed in front of them, mourn the loss of a mate - people who have heard this or seen this never forget.

This year a celebration of residents' favourite wildlife will run as Profiles across 2023 - simply to allow those who love their chosen 'critter' to speak for them a little, to remind us of what is here and what we feel connected to has feelings too.

Information about these species and how many or why we are losing them will also be included - just so we can think about how we, as individuals and as one community, can turn around that growing silence and emptiness closing in around us and these other ones we love.

Ultimately the founders of the Ringtail Posse are hoping everyone here chooses to become a Member of the Ringtail Posse and keep their other loved one ever present in their heart.

Reason?: To Protect Local Wildlife so it becomes 'common' and safer for our wildlife to be everywhere once more.

To join in please email us with 'Ringtail Posse' in the subject line - with so many local species of wildlife, vital insects and seals flopping around on the sand, there are several on the lists that haven't been claimed for guardianship yet - what's yours?

Round 4 of Ringtail Posse Profiles includes the following now officially joined Members:

Andrew Gregory – Australian Geographic Photographer, Spirit Of Adventure Awardee, Powerful Owl Project Volunteer: Powerful Owl Ninox Strenua

Nesting Season about to commence for Powerful Owls

Get involved at Powerful Owl Project: The Powerful Owl Project, in collecting data, helps land managers look after owls in their neighbourhoods. If you can help by letting the Powerful Owl Project coordinators about those you hear or see near you, they can all go on the register and in doing so you will have contributed to the conservation of these wonderful owls.

If you are interested in becoming a volunteer in Sydney, you would like to report a sighting, or would like to collaborate to help keep owls in the urban space, please contact powerfulowl@birdlife.org.au and keep up to date with the latest news by following the Powerful Owl Project Facebook page.

What is your favourite local wildlife species?

The Powerful Owl, although I also have an appreciation for all our owl species; I’ve had encounters locally with Barking Owl, Boobook Owl, Barn Owl and Masked Owl.

Why do you like the Powerful Owl?

Because they are an alpha predator they have status, and they are so magnificent and impressive. However, the old saying “as wise as an owl” applies to this species, they can live over 50 years, have favourite roost spots, are dedicated to their nest trees and form family bonds, these owl families are very close and exceptionally gentle with each other. The male and female also have distinct roles, the female is locked down in the hollow for months while the male feeds her.

I am familiar with all our local pairs and they all have different personalities. I have spent years gaining the trust of these birds, I’m very methodical and predictable and they know me by sight, they talk to me and have let me watch intimate moments and I have documented activity not seen before, such as bathing and hunting on the ground, taking prey into the nest hollow and many unusual vocalisations. I often describe them as being like big cats, like lions.

There are so many issues facing this species and they just keep struggling on, I suppose that’s what’s talking to my soul. Our local community should have learnt so many lessons from the loss of our koalas, however I’m seeing it happen again with this species.

How long have seen or heard the Powerful Owl?

I was always a casual observer, I started to really notice them when I began photographing at night but the reality is the owls found me and I’ve been observing them continually for 8 years now. I’ve spent countless hours over many years observing what’s going on, also using camera traps. I work with birdlife and the Powerful Owl project Sydney wide, gathering data and rescuing and releasing owls. I’m also a WIRES raptor volunteer and take injured owls to Taronga Zoo Hospital for rehabilitation and have released owls locally. I released a fledgling in Avalon that was originally rescued by Tom McGee, another local WIRES rescuer. A year later it was hit by a car and survived, it had moved 25kms away, I picked it up from Taronga and released it a second time. Young owls may form small adolescent groups in areas where it is easier to catch prey, such as golf courses. It takes a long time for an owl to learn to be a proficient hunter. I’ve watched young owls who are frustrated and hungry because they are not able to catch prey.

I’ve documented all our local nest trees and have captured some amazing footage. Locations of these nest trees are kept secret. During nesting season the owls are easily spooked, and have abandoned nest trees when disturbed, they like to hide and are harassed by other birds when discovered.

Have you noticed any changes in the number of Powerful Owls in your local neighbourhood?

Last year was the worst season ever, Powerful Owl numbers are down 30% Australia wide. The fledgling rate is less than 1, so not every pair that breeds will have a successful fledgling. Young owls can die in the hollow from lack of food or other causes. They also have to contend with land clearing (sometimes by bush regeneration and hazard reduction which can burn out hollows).

Deaths and injury can be due to car and window collisions, including glass pool fences, rat poison (from taking poisoned rats), entanglement and animal attack. Young owls are heavy and poor flyers, they spend the first few weeks on or near the ground and are easy prey. Current council policy means our wildlife isn’t protected in wildlife protection areas and much of our potential habitat (not just for owls but all species) is not being utilised.

Our local pairs now rarely have 2 fledglings, whereas 5 years ago it was common. Our fledglings also leave the local area when they are about 6 months old. I have access to a lot of data so it’s possible to work out what’s going on, generally numbers for all local species are down, also by observing the prey taken by owls we can consider the state of other species. Over the last few years in Pittwater so many trees have been taken out that loss of canopy has left gaps in our wildlife corridors, including backyard habitat.

I always get a sense of awe looking at a young owl looking out of a hollow (that may in a tree hundreds of years old) for the first time and being conscious that they may live for 50 years. I still remain optimistic that Pittwater can retain enough wildlife to have a balanced and sustained eco system, that still allows us to live with this magnificent species.

Editor's notes:

There is not one record for Powerful Owls either rescued and released or not for our area in the published NSW Department of Planning and Environment data, even though there are multiple records within our area by wildlife carers of rescuing these birds, which is recorded in their data, along with those kept by this news service, sometimes to take them to local vets or Taronga zoo for help. This underlines another 'missing' part of accurately assessing just how much wildlife we are losing across the LGA when the records do not reflect what is actually occurring in the area. As found by the study ''Trends in wildlife rehabilitation rescues and animal fate across a six-year period in New South Wales, Australia'', around 50% of data is being excluded even though those wildlife species are actually being rescued, with most of those species rescued either dying or being euthanised due to the extent of their injuries.

These same records state 3 emus/cassowaries have been rescued locally - a desert bird in the first case, and one that lives in northern Queensland and New Guinea in the other (?!) - certainly not common on the northern beaches of Sydney and must have 'winged it' from a cage somewhere - it's a jailbreak! - only 2 survived.

However, there are records for other owls species named by Andrew in the 2013-2021 data. There have been 146 Hawk Owl rescues, just 35 released. Eastern Barn Owls, Masked Owls and Sooty Owls account for 28, just 5 released; 2 of these are threatened species.

The Tawny Frogmouth, although not an owl, accounts for 861 rescues and just 222 releases.

This means we have lost at least 773 nocturnal bird species that have not been 'excluded' from the data; or an average of 100 a year, or one is being killed every 3rd day, and 2 each week.

If you are not hearing the soft calls of owls at night as much any longer - there is a clear reason why and why we need to stop cutting down their homes, the trees.

Marita Macrae OAM - Co-Founder Pittwater Natural Heritage Association, Ruth Readford Lifetime Achievement Award (2013): Pale-Lipped Or Gully Shadeskink Saproscincus Spectabilis

What a name! Saproscincus - say SAP-roh-SKINK-uss -meaning "rotten skink" in reference to their use of decaying leaf litter as a microhabitat. 'Spectabilis' means able to be seen, spectacular, remarkable - not particularly suitable for this species as neither its discreet colours nor retiring habits make it eye-catching. Its skin is speckled various browns, without stripes or obvious markings, except for a paler lip.

Gully shade skink Saproscincus spectabilis Skink Avalon. Photo: Marita Macrae

It is one of Australia's 459 skink species, of which the biggest skink is the familiar Blue-tongue. This one reaches about 10cm.

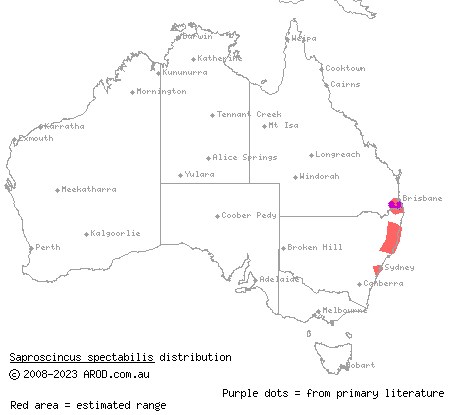

Saproscincus-spectabilis-range-distribution-map. Distribution map from: https://arod.com.au/arod/reptilia/Squamata/Scincidae/Saproscincus

You won’t see this skink on sunny fences or darting about out in the garden. It likes shade and moist areas with decaying leaf litter. Here are its prey of tiny insects and hiding places from its predators such Kookaburras and Magpies.

While sun-loving skinks are very quick to react to movement, rushing to shelter out of sight, this skink has a calmer temperament. It will allow an observer to come quite close, raising its head on an elegant neck, turning to look at you steadily with a wary yellow eye.

Gully Shade Skink. Photo: Marita Macrae

Several live on or near my shady front and back porches. It can easily slip under the screen doors and come into the house, presumably helping with control of tiny insects, so is a welcome visitor.

Gully Shade skink inside. Photo: Marita Macrae

Strong claws on front and back feet enable it to climb up onto shady vegetation and up the vertical rendered wall at the back of the house, from where it can move onto the various pot-plants. Once I found a pair in a conjugal embrace among the roots of a moth orchid.

Gully Shade skinks mating. Photo: Marita Macrae

At this colder time of year I don’t see these skinks so much, as they are undergoing brumation, a resting state for reptiles comparable to hibernation in warm blooded animals.

I do enjoy seeing this engaging native animal in and around the house.

Editor's notes:

There have been 23, 916 skinks rescued across the whole of NSW during the 8 year data period, and 6, 833 released after being cared for, with 4 listed as threatened species among this number - of these threatened species, 36 were rescued and just 12 released. In our area 913 have been rescued across the data period and 239 of these were returned to their homes. The bulk of skink rescues in our area are blue-tongued lizards due to animal attacks - pet cats and dogs - and basking on warm roads and being run over. The infections from bites are hard to treat and take wildlife carers a long time to help them with, if they can be. Disinfecting and dressing changes each day for weeks are required - as well as specialist food.

Having skinks around will help control crickets, moths and cockroaches. The larger blue-tongued lizard will eat snails - a good reason not to use pesticides and insecticides in your garden as this will kill them, especially snail pellets.

If you want to encourage skinks of all shapes and sizes to take up residence in your garden and gobble up all those cockroaches, install some nice basking rock areas, some bark and a log and place these near dense bushes or shelter so they have a bolt hole when predators happen by.

Jools Farrell - Captain Paul Watson Foundation: Whales & Seals

What is your favourite local wildlife species?

First question well really hard to just pin down one as I am sure you would know, but for me it's Marine Mammals such as Whales and Seals.

Why do you like whales and seals?

2The whales are just so majestic and such a delight to see them on their migration up the east coast especially the southern migration when they have calves with them just love the activity from the young whales when Mum is teaching them behaviours such as breaching.

I have had quite a lot of contact with whales especially the Humpback, the most memorable and also most heart breaking was sitting out with a juvenile Humpback which had become entangled in a shark net at Whale Beach a few years ago. I spent 5 hours sitting in a small boat monitoring this Humpback whilst waiting for the disentanglement team from NPWS to arrive, which they did, and this young whale was freed with no injuries.

In regards to seals I monitor the colony of fur seals at Barrenjoey and also have monitored various fur seals and also leopard seals who have hauled out on our local beaches for a rest just love seeing them thermoregulating in the water at Barrenjoey which is normal behaviour for them.

How long have seen or heard whales and seals?

I have been aware of whales and seals for as long as I can remember but did become very aware of them when I started my nursing training at MVDH in the early 70’s.

Have you noticed any changes in the number of whales and seals in your local neighbourhood?

In regards to numbers of these marine mammals, yes I have definitely seen an increase in both the whale and seal populations and they are increasing in numbers every year.

I'm happy to speak out about the net situation especially the shark nets which are a nightmare and death traps for many marine creatures, as for ghost nets and fishing gear; this is also a nightmare.

Boat strikes are also an issue especially with the population of whales and seals increasing.

Seismic testing; well don’t get me started on that, it is just awful what this does to the marine creatures, it disturbs their sonar/hearing even bursting their eardrums, causing death and also strandings.

Offshore wind farms are also a nightmare with the noise which is created in the ocean. We have plenty of land here in Australia where these wind farms can be built, they don’t need to be in the ocean.

A Barrenjoey Seal

Nicole Romain - Founder Save The Northern Beaches Bushlands (Lizard Rock): Yellow-Tailed Black Cockatoos Calyptorhynchus funereus

What is your favourite local wildlife species?

One of my favourite wildlife species is the yellow-tailed black cockatoos and all the variations of black cockatoos including red-tailed and glossy black cockatoos.

Why do you like yellow-tailed black cockatoos?

I love it’s bird call and hearing a flock fly over. When I first moved to Belrose there was a large flock of yellow-tailed black cockatoos fly over making their call and was amazing to see and hear. It touches my soul by its magnificent call and graceful flying normally in at least three or more in a flock and just knowing they are here and currently in our local environment and area.

How long have seen or heard yellow-tailed black cockatoos?

I see them often when I have been on bushwalks in Belrose and quite close to where I live.

Have you noticed any changes in the number of yellow-tailed black cockatoos in your local neighbourhood?

Although I have not noticed a decline in numbers locally due to our natural environment remaining intact and not interfered with by further developments or loss of habitat, should this be removed we would lose the food trees for these wonderful birds. It has been acknowledged right across NSW and Australia this bird is in rapid decline due to native habitat clearance, with a loss of food supply and nest sites.

Editor's notes:

There have been 3, 819 parrots rescued across this LGA according to the 2013 to 2021 data made available, or just over 477 a year during this 8 year data period, and 823 released, meaning we have lost just over 8 parrots every single day during the 8 year data period available. Across the whole of NSW 83, 124 have been rescued and after those that were released are deducted we are losing 177 each day.

Yellow-tailed Black-Cockatoos were once content to feed on the seeds of native shrubs and trees, especially banksias, hakeas and casuarinas, as well as extracting the insect larvae that bore into the branches of wattles. Now, after the establishment of extensive plantations of exotic Monterey Pines, the cockatoos may feed more often by tearing open pine cones to extract the seeds. The population on South Australia’s Eyre Peninsula is now reliant on the seeds of the Aleppo Pine, a noxious weed, as its preferred habitat, as its Sugar Gum woodlands has become extensively fragmented.

Research featured in the ‘State of Australia’s Birds 2015‘ headline and regional reports indicates a significant decline for the Yellow-tailed Black Cockatoo (and some other parrot species) in the East Coast.

BirdLife Australia lists habitat destruction as the primary risk to this bird.

The Yellow-tailed Black-Cockatoo inhabits a variety of habitat types, but favours eucalypt woodland. The favoured food is seeds of native trees and pinecones, but birds also feed on the seeds of ground plants. Some insects are also eaten. They are often spotted in small family groups in native forests, heathland and pine plantations, where they feed on wood-boring larvae and seeds. They tend to congregate in larger flocks during the breeding season, which runs from March to August in NSW. The male yellow-tailed black cockatoo courts by puffing up his crest and spreading his tail feathers to display his yellow plumage. Softly growling, he approaches the female and bows to her three or four times. His eye ring may also flush a deeper pink.

Nesting takes place in large vertical tree hollows of tall trees, generally eucalypts, which may be living or dead. A 1994 study of nesting sites in Eucalyptus regnans forest in the Strzelecki Ranges in eastern Victoria found the average age of trees used for hollows by the yellow-tailed black cockatoo to be 228 years. The authors noted that the proposed 80–150 year rotation time for managed forests would impact on the numbers of suitable trees.

Both sexes construct the nest, which is a large tree hollow, lined with wood chips. The female alone incubates the eggs, while the male supplies her with food. Usually only one chick survives, and this will stay in the care of its parents until the next breeding season.

Like other cockatoos, this species is long-lived. A pair of yellow-tailed black cockatoos at Rotterdam Zoo stopped breeding when they were 41 and 37 years of age, but still showed signs of close bonding.

Yellow-tailed black cockatoos are one of two species of black cockatoos found in NSW. The other is the much less common south-eastern glossy black cockatoo, a species in decline, particularly after losing crucial habitat during the severe bushfires of 2019/2020, and listed as vulnerable nationally in August 2022.

The south-eastern glossy black cockatoo is a specialist eater and feeds on she oaks, which is why we will sometimes see them in Pittwater and why we need to stop cutting down their food; the trees.

Glossy Black-cockatoo, Calyptohynchus lathami, at Clareville - photo by Paul Wheeler, this species also visits McKay Reserve, Palm Beach, annually to feed on these trees