“Humble” is not a word my colleagues would use to describe me, especially early in my career.

In fact, when word got around that I was researching humility, I suspect more than a few choked on their coffee.

And even though I have spent over a decade exploring the concept as an attribute and as a practice, it wasn’t until I recently reflected on my own professional challenges that I truly understood how to embrace humility.

I want to share my journey, but first it is important to understand what humility is – and isn’t. It’s been extolled as a virtue for centuries, but it’s often mischaracterized.

In today’s culture, it can be mistaken as a humblebrag, which disguises a boast as modesty – for example, “I really hate talking about myself, but people keep asking how I managed to run a marathon while working full time.” Or it can resemble impostor phenomenon, the persistent experience of feeling intellectually or professionally fraudulent despite clear evidence of competence or success.

But research shows that humble people hold accurate views of their own abilities and achievements. They openly acknowledge their mistakes and limitations and are receptive to new ideas. Overall, they recognize their places within a larger whole and genuinely appreciate the value of others.

Humility doesn’t always earn praise. Sometimes the humble may be seen as meek, subservient or self-abasing.

For instance, many people praised former New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern’s empathetic, self-effacing leadership during the COVID-19 pandemic, with an openness and deference to experts. But some critics dismissed it as weak or soft. These negative views show the various ways people “see” humility.

Generally, though, when humility is understood as grounded self-awareness rather than self-erasure, it’s viewed as something worth cultivating and practicing. We see openness, curiosity, acknowledgment of others and a lack of ego in fictional characters like Ted Lasso, hero of the same-titled Apple TV series; Samwise Gamgee in the “Lord of the Rings” books; and Jean-Luc Picard, commander of the USS Enterprise in “Star Trek: The Next Generation.”

Humility is also evident in public figures, such as former President Jimmy Carter, children’s television host Fred Rogers, and Nelson Mandela, the Black nationalist who served as the first Black president of South Africa.

I’m a sociologist with a focus on medical education and health care providers. At Arizona State University’s Edson College of Nursing and Health Innovation, I explore issues including causes of burnout, elements of team-based care and opportunities for emphasizing the human side of health care. In recent years, my work has focused on humility.

From my research and my own experience, I’ve learned that true humility isn’t self-erasure. It’s a sense of security and confidence that your value doesn’t depend on recognition and that you are just one member of a larger system with a multitude of contributors. By removing the need to dominate, humility fosters openness to collaboration, innovation and an awareness of how the systems around us work.

Still, in a world of Instagram likes and LinkedIn accolades, humility can be the virtue everyone seems to admire but few practice It’s the one we say we want – until it requires us to confront the parts of ourselves that crave affirmation.

Climbing the professional ladder

I tend to stand out in a crowd. I’m 6-foot-4, with close-cropped hair, a heavy beard and tattoos. I also push myself to stand out professionally.

Starting in graduate school, I was determined to make my voice heard and sought after. I pursued nearly every opportunity, committee and position that came my way. No role was too small for me to accept.

I strived to present my work in top-tier journals and at conferences, and I cold-called prominent scholars to propose working together. And I constantly shared my findings and thoughts on social media.

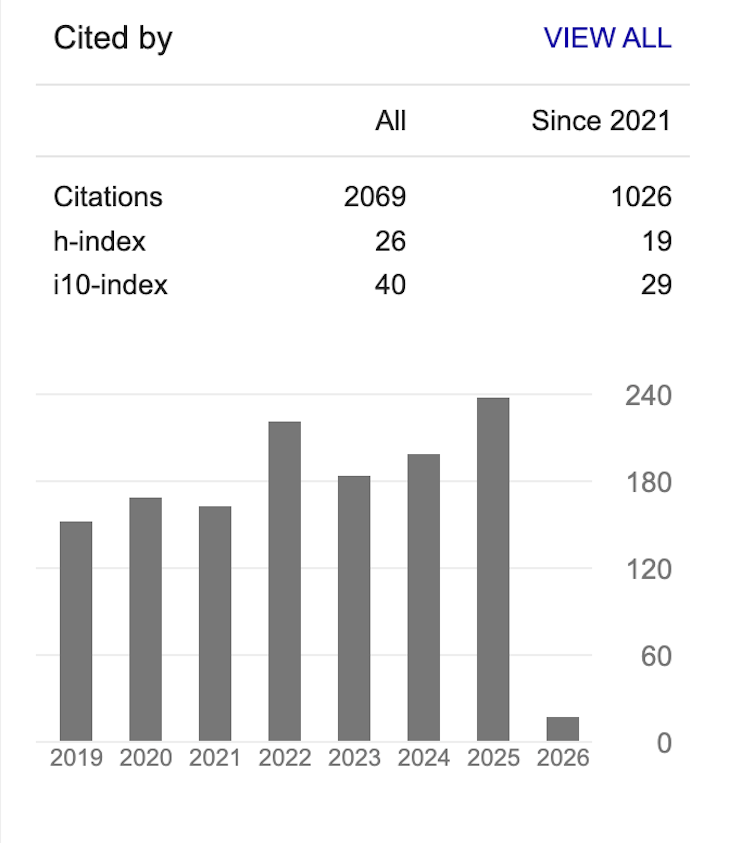

Like many workplaces, the academic world has a set of defined success metrics, such as publications, citations of your work, grant funding and teaching evaluations from students. School culture and leadership influence what each college or university considers more or less valuable among those measures. To advance and get promoted, particularly to get tenure, it’s important to learn at an early stage what one’s department, college or university truly prioritizes.

I wanted to get tenure but also to be seen as an active citizen of academia – energetic, outspoken and unafraid to push boundaries. When my department chair described me as having my hair on fire, I took it as a compliment. I called it “making positive noise.”

Initially, the system rewarded that noise. I earned tenure at the University of Delaware and received departmental, college and national awards. I also was appointed to serve as associate dean and to direct a new research center. I felt validated, visible and valuable.

The sociology department at the University of Delaware had a typical academic culture that’s often summarized as “publish or perish.” The most important measures of scholars’ work were writing, publishing their work in respected journals and having other researchers cite those studies. Securing external funding from government, private companies or foundations was valued but was not as high a priority as publishing.

A new beginning that felt like an end

In 2020 I received a new opportunity at Arizona State University, a much larger school that branded itself as a hub of innovation and entrepreneurship. I was offered the chance to direct the Center for Advancing Interprofessional Practice, Education and Research and to step into the shoes of a leader I deeply admired. I arrived expecting to be a big fish in a bigger pond.

I couldn’t have been more wrong.

I showed up imagining there’d be a bit of buzz around my arrival given my time at the University of Delaware. But reality didn’t match the script: no greeting, office or nameplate marked my place when I arrived.

Early conversations with administrators weren’t about my research or teaching visions – the things that I thought set me apart. Instead, I felt they tended to focus on how much external funding I could raise from foundations and government agencies. My new colleagues often spoke in a shorthand of grant-based acronyms when referring to what projects they were working on, a “language” I was woefully unfamiliar with.

To make matters worse, I arrived during COVID-19, with classes either canceled or taught online and faculty members working mainly from home. The hallway chatter, open doors and spontaneous collaboration that I was accustomed to were absent. I began to feel alienated and disoriented as a scholar.

Even after ASU resumed in-person classes in the fall of 2021, I felt like the silence and distance lingered. No students waited for office hours. I struggled to make connections with my colleagues. I eagerly proposed collaborations when really everyone was just trying to find their footing in this new era of education.

My proposals for new classes and curricular programs hit up against institutional barriers I was unaware of. At one point, a college administrator asked, “How do we get you on other people’s grants?” – a question that I took to imply that they felt my research wasn’t strong enough.

It appeared that my colleagues in Edson College were accustomed to these values and spoke the language. I was a stranger in a strange land. Although I was producing some of my best work, measured in terms of publications and citations, I felt no one seemed interested. I had come from an environment where I felt known and valued to one where I seemed to be a nobody.

I felt as though I needed to staple my resume to my forehead and parade around the hallways asserting, like Ron Burgundy in the movie “Anchorman,” “I’m not quite sure how to put this, but … I’m kind of a big deal. People know me.”

The impact of feeling unseen

For people who have built careers by being highly engaged and visible, suddenly feeling unseen can be devastating. In any profession, a fear that you don’t belong at your workplace can be debilitating and make you question your own value.

I sought advice from peers and college leaders, and even hired a professional coach. Things only worsened. Curricular proposals were stalled or turned down. My center was shuttered in a restructuring, although it was meeting its goals and earning international recognition.

At first, I blamed ASU and Edson College for my feelings of disconnection. I thought the leadership structure and style was dysfunctional; that many colleagues were cold, unfriendly and conformist; and that the college’s stated values were inauthentic.

This series of what I came to call “unacknowledgments” sent me into a personal and professional tailspin. Negativity and self-doubt consumed me, and I truly worried that my career was over. Had I been blackballed? Why did it feel as though no one cared?

When the noise turns inward

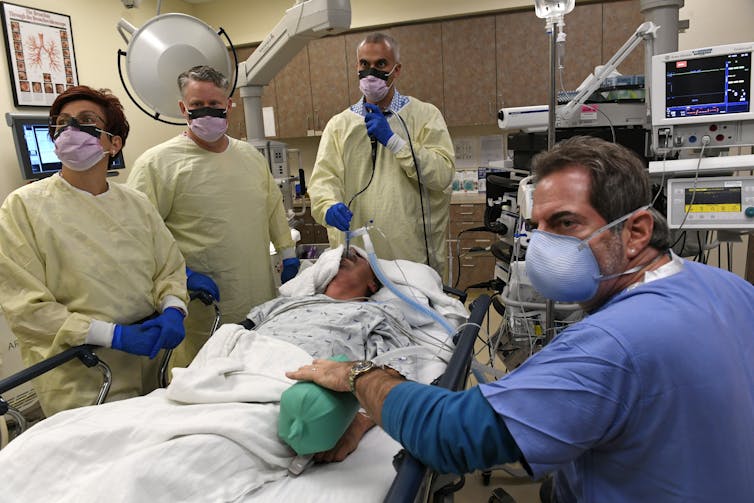

I had spent years studying empathy – the ability to understand and feel what someone else is feeling – and how to cultivate it among health care professionals and students in order to support more patient-centered care. To that end, at the University of Delaware I had developed a program designed to foster empathy across health professions. It aimed to help students see one another as collaborators, build shared respect and recognize their collective role on the same health care delivery team.

But when I further analyzed the program’s outcomes from my office at ASU, I realized that empathy wasn’t enough. It could help students feel with others, but it didn’t necessarily help them see themselves, or others, differently.

I realized that what I really wanted the students to develop was humility. This step would require them to recognize their limits, accept that they were fallible, see themselves as part of a larger team and value others’ contributions.

That realization changed my research trajectory – and eventually, my professional life.

Research becomes a mirror

Initially, I approached humility solely as a scholar. I examined the history of the concept and gaps in existing research on it, and I analyzed how humility was connected to uncertainty and the impostor phenomenon. I explored how humility could enhance team-based care and developed a new way to define humility among health care professionals in order to promote more collaboration and patient-centeredness.

As my own professional world began to unravel, and as I dived deeper into the concept of humility through my research, something unexpected happened. I realized that humility wasn’t just an idea to study – it was becoming a mirror that made me rethink my own perspective.

Slowly, I began to see how pride and insecurity were entwined in my reactions to my new setting at ASU. I realized that my need to be noticed, and my insistence that others validate my worth, represented my own kind of arrogance.

Perhaps my ambition had been less about contributing and more about gaining external validation. I had lost the selfless wonder and awe that drive scholarly inquiry and curiosity. And now I had to confront what remained when the spotlight dimmed.

Humility, I began to understand, wasn’t just an abstract concept to explore “out there” among others. I needed to hone it internally by thinking beyond myself. By decentering my ego, I realized that I could nurture and sustain curiosity in its own right.

In short, I needed to practice what I was preaching. It wasn’t an easy lesson. I assume that cultivating humility never is.

To that end, I felt that it was essential to develop a program to help build humility “muscles.” In 2024 I developed HIIT for Humility, an online training package for individuals or groups, modeled after the fitness concept of high-intensity interval training. This program provides evidence-based strategies to help users start building “habits of humility,” such as acknowledgment of others and self-awareness.

Just as physical exercise requires consistency to produce results, so does the cultivation of humility. Leaning into HIIT for Humility workouts gradually eased my sense of alienation and defensiveness. I became more appreciative of others, less quick to judge and better able to listen to others’ perspectives. In doing so, I started to feel more confident and secure.

While I still took pride in my work, I began to see that my contributions were not the only ones that mattered. I also found that I could stretch into unfamiliar but necessary tasks, such as working harder to win federal and foundation grants and seeing the value of my colleagues’ contributions to science.

Why am I here?

Only a few years into this process, I can see that ASU and Edson College have unintentionally taught me humility by signaling, often quietly, which contributions are deemed essential and which forms of success carry the most weight. Navigating stalled proposals, shifting priorities and structural reorganizations have required me to recalibrate my ego, expectations and identity.

Not being seen as a “big fish” and being expected to persist without consistent recognition have required me to understand my work as part of a larger system with differing values and, at times, challenging constraints. Shifting to ASU forced me to rethink my identity as a professor and to reevaluate my sense of purpose from the inside out.

A colleague of mine often asks students who he feels are coasting along, “Why are you here?” Lately, I’ve taken that question personally. What is the point of being a professor – writing papers, submitting grant proposals, teaching courses? Why did I choose this path in the first place?

When I feel unseen, unheard or unappreciated, pondering why I’m here helps ground me. For anyone who is struggling to feel visible or valued at work, I strongly recommend considering this simple question.

Over time, I’ve stopped needing to be the big fish in the pond and measuring my worth in titles and awards. I now see that my responsibility as a scholar, teacher and human being is to stay curious, listen more deeply and make space for others’ voices.

Embracing humility, and consistently using my humility muscles, have helped me realize that I’m here to be part of the creative energy of academia, do the work and cultivate curiosity in my students, my peers and myself.![]()

Barret Michalec, Research Associate Professor of Nursing and Health Innovation, Arizona State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The powerful owl (Ninox strenua), a species of owl native to south-eastern and eastern Australia, is the largest owl on the continent. It is found in coastal areas and in the Great Dividing Range, rarely more than 200 km (120 mi) inland.

The powerful owl (Ninox strenua), a species of owl native to south-eastern and eastern Australia, is the largest owl on the continent. It is found in coastal areas and in the Great Dividing Range, rarely more than 200 km (120 mi) inland.

Biba was a London fashion store of the 1960s and 1970s. Biba was started and run by the Polish-born Barbara Hulanicki and her husband Stephen Fitz-Simon.

Biba was a London fashion store of the 1960s and 1970s. Biba was started and run by the Polish-born Barbara Hulanicki and her husband Stephen Fitz-Simon.

The National Library of Australia provides access to thousands of ebooks through its website, catalogue and eResources service. These include our own publications and digitised historical books from our collections as well as subscriptions to collections such as Chinese eResources, Early English Books Online and Ebsco ebooks.

The National Library of Australia provides access to thousands of ebooks through its website, catalogue and eResources service. These include our own publications and digitised historical books from our collections as well as subscriptions to collections such as Chinese eResources, Early English Books Online and Ebsco ebooks.

Ingleside Riders Group Inc. (IRG) is a not for profit incorporated association and is run solely by volunteers. It was formed in 2003 and provides a facility known as “Ingleside Equestrian Park” which is approximately 9 acres of land between Wattle St and McLean St, Ingleside. IRG has a licence agreement with the Minister of Education to use this land. This facility is very valuable as it is the only designated area solely for equestrian use in the Pittwater District.

Ingleside Riders Group Inc. (IRG) is a not for profit incorporated association and is run solely by volunteers. It was formed in 2003 and provides a facility known as “Ingleside Equestrian Park” which is approximately 9 acres of land between Wattle St and McLean St, Ingleside. IRG has a licence agreement with the Minister of Education to use this land. This facility is very valuable as it is the only designated area solely for equestrian use in the Pittwater District.

Legal Aid NSW has just published an updated version of its 'Fined Out' booklet, produced in collaboration with Inner City Legal Centre and Redfern Legal Centre.

Legal Aid NSW has just published an updated version of its 'Fined Out' booklet, produced in collaboration with Inner City Legal Centre and Redfern Legal Centre.