March 12 - 18 2023: Issue 575

Ringtail Posse: 2 - March 2023

Kevin Murray: Tawny Frogmouth - Kayleigh Greig: Red-Bellied Black Snake - Bec Woods: Australian Water Dragon - Margaret Woods: Owlet-Nightjar - Hilary Green: Butcher Bird - Susan Sorensen: Wallaby

Definition from

Ringtail: from the 'Common Ringtail Possum' which is not so common anymore in urban areas. The Common Ringtail Possum is found along the entire eastern part of Australia and south west Western Australia. They are also found throughout Tasmania. The western ringtail possum is a threatened species under State and Commonwealth legislation. In Western Australia the species is listed as Critically Endangered fauna under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016.+

Posse: noun. 1 : a large group often with a common interest 2 : a body of persons summoned by a sheriff to assist in preserving the public peace usually in an emergency 3 : a group of people temporarily organised to make a search (as for a lost child) 4 : one's attendants or associates.

In recent approved DA’s Council is listing as a requirement of consent in Assessment reports to look after the other residents of this area, the wildlife. On blocks where people wish to remove large amounts of trees that are clearly homes for local fauna a wildlife expert must assess these prior to any removal taking place, nesting boxes are required to be installed afterward and Ecologists must be on site during their removal. Other recent examples and instances are:

Bandicoot/Penguin (Avalon)

Long-nosed Bandicoots & Little Penguins – Best Practices for Residents

Residents are encouraged to follow a number of Best Practices to assist with the protection and management of the endangered populations of Long-nosed Bandicoots and Little Penguins:

Long-nosed Bandicoots, Little Penguins and other native animals should never be fed as it may cause them nutritional problems, hardship if supplementary feeding is stopped, and it may increase predation.

Feral cats or foxes should never be fed or food left out where they can access it, such as rubbish bins without lids or pet food bowls, as these animals present a significant threat to Longnosed Bandicoots, Little Penguins and other wildlife.

The use of insecticides, fertilisers, poisons and/or baits should be avoided on the property.

Garden insects will be kept in low numbers if Long-nosed Bandicoots are present.

When the North Head Long-nosed Bandicoot Recovery Plan is released it should be implemented where relevant.

Dead Long-nosed Bandicoots or Little Penguins should be reported by phoning Manly Council on 9976 1500 or Department of Environment and Conservation on 9960 6266.

Please drive carefully as vehicle related injuries and deaths of Long-nosed Bandicoots and Little Penguins have occurred in the area. Care should also be taken at night in the drive way when moving cars as bandicoots will seek shelter beneath vehicles.

Cat/s and or dog/s that currently live on the property should be kept indoors at night to avoid disturbance/death of native animals. Ideally, when the current cat/s and/or dog/s that live on the property no longer reside on the property it is recommended that they not be replaced by new dogs or cats.

Report all sightings of feral rabbits, feral or stray cats and/or foxes to N B Council.

And;

Dead or Injured Wildlife (Palm Beach)

If construction activity associated with this development results in injury or death of a native mammal, bird, reptile or amphibian, a registered wildlife rescue and rehabilitation organisation must be contacted for advice.Protection of Habitat Features

All natural landscape features, including any rock outcrops, native vegetation and/or watercourses, are to remain undisturbed during the construction works, except where affected by necessary works detailed on approved plans.

Reason: To protect wildlife habitat.

The Reason given in all instances is: To protect native wildlife.

This follows on from the 2022 Local Government NSW Conference where a Motion was passed - That Local Government NSW lobby the NSW Government to:

- In conjunction with industry associations, introduce enforceable standards for the preparation of flora and fauna management plans.

- Consider Codes of Practice and Guidelines for handling native wildlife and other best practice and animal welfare laws in development of the standards.

- Consult with Councils, National Parks and Wildlife Service, Ecological Consultants Association of NSW, wildlife rescue organisations and other relevant agencies in the preparation of standards.

Such a standard should include requirements for:

- Pre-clearance surveys to be carried out to establish which species are present on the site, including identification of any threatened and native species.

- The identification of suitable nearby areas where wildlife could possibly be relocated.

- The provision of possum, glider and bat boxes sufficiently in advance of vegetation clearing to allow wildlife time to discover the boxes and become familiar with them.

- Compliance with the NSW Code of Practice for Injured, Sick and Orphaned Protected Fauna and the licencing requirements contained in the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016.

- Best practice for wildlife handling and care (including contact with local wildlife rescue groups).

- Reporting of injured or killed fauna to the NSW Department of Planning, Industry and Environment to enable the data to be used in statewide biodiversity monitoring programs.

The premise of this is that mandatory pre-clearance surveys to establish what wildlife lives there before works commence, and to document this in a formal way, should be required on any site that has vegetation and for which a DA has been approved. The experience is that often vegetation is removed before an application is submitted, often leaving wildlife with no home. Wildlife then ends up on roads dead or dies after being displaced/evicted.

One wildlife carer cited a recent Pittwater case of a powerful owl pair site that had had vegetation removed to make the development more likely to proceed – the nest and two babies were destroyed.

‘It’s hard to prove wildlife is/was present after the clearing as they aren’t there.’

‘Once trees and vegetation are removed the problem is where do these animals go?’

Powerful Owls are also not so common anymore in urban areas.

However it's clear human residents of this LGA have a deep and abiding love for and connection to these other furry, scaled, finned and feathered beings. We listen for them during the night, happy when we hear their footsteps scampering across our rooves or their soft hoots across the valleys.

Human residents are distressed when they find injured wildlife or witness wildlife being attacked.

Data kept by the NSW Environment Department, although only listing incidents from June 2013 to June 30 2020, shows that 28,542 wildlife animals have been rescued in our area between June 2013 and June 30 2020. That's well over 4000 each year. Of these 41 were threatened species (504 threatened animals rescued - only 111 threatened animals released).

''This study draws on 469,553 rescues reported over six years by wildlife rehabilitators for 688 species of bird, reptile, and mammal from New South Wales, Australia.... Of the 364,461 rescues for which the fate of an animal was known, 92% fell within two categories: ‘dead’, ‘died or euthanised’ (54.8% of rescues with known fate) and animals that recovered and were subsequently released (37.1% of rescues with known fate).''In total, there were 872,087 records reported during the six-year (2013–14 to 2018–19) study period. Just over 97% of these came from three animal groups–birds, mammals, and reptiles. Of the total number of records, 402,534, (46%) were excluded from the descriptive analysis because they: a) did not contain any information about the animal, or the animal’s identification was ambiguous and could not be placed within a group (e.g. an ‘unidentified animal’); b) contained only sightings of animals and were not attended to in some way by a wildlife rehabilitator; c) were records of amphibians (373 records) or non-vertebrate fauna (e.g. spiders, insects, etc.); d) were non-avian marine vertebrates such as whales, seals, sharks, rays, fish etc; e) were reported as floating, drowned, or washed up animals (deemed an ambiguous cause for rescue, n = 48); f) contained both an ‘unknown’ cause for rescue and an ‘unknown’ fate; or f) were an introduced or spurious species (e.g. extinct, or out of known range). These exclusions resulted in a dataset for descriptive analysis of 469,553 records i.e. 54% of the initially reported amount.''

Data to 30 June 2021 lists of the 5, 235 animals rescued during that 2020 to 2021 period just 1,573 were released.

Many people state we are the generation witnessing the extinction of urban wildlife. There has been generation after generation of humans living alongside and with wildlife, until this one.

It's not just the Pittwater koalas that have gone, other species, like the ringtail possum or long-nosed bandicoot are disappearing, along with their joyful snuffles and squeaks, from our urban backyards and the trees that tower over them.

There is a growing silence at night for those species that forage for food then - possums, wallabies, owls. The same is occurring for those that are active during daylight.

Although many point to the impacts of cat and dog attacks due to irresponsible owner, there is also what is termed the 'inconvenient possum' in a roof or garden shed, because its home tree has been cut down. These are caught by those hired, some of whom have little knowledge or scruples, and release them into areas out of their home range - a death sentence for that possum as this species is territorial, along with requiring certain food trees in order to eat, to survive.

There is predation by other introduced species - readers regularly send in photos and videos of foxes roaming and killing at night.

There are roadkill black spots, places where wallabies or turtles or possums used to cross the area where a road has been cut through and a speed limit that means death for wildlife. There are no 'speed humps' in place, and no plan at a local, state or federal government level to istall these. Residents and wildlife rescuers have reported some drivers 'aiming straight for' a stricken animal.

There is the razing of blocks of land for development prior to any required assessment of the environment taking place to circumvent those requirements so a report can state 'nothing present'. There is nothing present because its habitat has been cleared or the wildlife killed by these actions.

Our local wildlife carers are getting exhuasted, state there have been so many, too many so far this summer - they are increasingly heartbroken with all the babies they lose, they cry every day, and then pick themselves up and get on with trying to save the next critter, and the next.

Wildlife carers are all volunteers - they do the rescues, sometimes horrific rescues, run to and fro from the great local vets who help out trying to save them, they gather or pay for the food, for the milk, for the petrol, for the electricty to keep bubs warm. There are no grants or funding for Australia's wildlife carers - they have to raise funds through running events, raising awareness, collecting cans for a 10 cent return.

Similarly we are not in denial that all our local wildlife feels and thinks - they cry when their babies are killed in front of them, mourn the loss of a mate - people who have heard this or seen this never forget.

This year a celebration of residents' favourite wildlife will run as Profiles across 2023 - simply to allow those who love their chosen 'critter' to speak for them a little, to remind us of what is here and what we feel connected to has feelings too.

Information about these species and how many or why we are losing them will also be included - just so we can think about how we, as individuals and as one community, can turn around that growing silence and emptiness closing in around us and these other ones we love.

Ultimately the founders of the Ringtail Posse are hoping everyone here chooses to become a Member of the Ringtail Posse and keep their other loved one ever present in their heart.

Reason?: To Protect Local Wildlife so it becomes 'common' and safer for our wildlife to be everywhere once more.

To join in please email us with 'Ringtail Posse' in the subject line - with so many local species of wildlife, vital insects and seals flopping around on the sand, there are several on the lists that haven't been claimed for guardianship yet - what's yours?

Round 2 of Ringtail Posse Profiles includes the following now officially joined Members:

Kevin Murray

Tawny Frogmouths

“Build it and they will come”, so they say. So, after we demolished our backyard pool, we filled the space with a mini-rainforest - and they came... frogs, possums, bandicoots, lorikeets, magpies, Brush Turkeys, kookaburras. But the one animal we really wanted to visit had eluded us for years. Until…

We heard him long before we saw him. The soft but distinctive “oom oom oom...” of his night-time call hinted at his presence, but the Tawny Frogmouth producing that sound remained hidden by the darkness at night, and by his superb camouflage during the day.

And then, one evening we saw him... perched atop our backyard fence-post, as if he were a slightly ruffled extension of that same post. We were so excited that he had chosen our backyard to rest, albeit temporarily. Or so we thought. The very next evening we heard a soft chirruping noise outside our bedroom window, occasionally interrupting the now-familiar “oom oom oom...”. After our eyes had adjusted to the growing darkness we saw our Tawny friend sharing a tree branch with two others, one almost as large as him, and another quite a bit smaller. A family? We just had to investigate further.

A little research told us that Tawny Frogmouths are often mistaken for owls, but are more closely related to nightjars. By day they roost on the branches of trees, usually choosing greyish-coloured limbs to match their greyish, mottled plumage. To make the most of this deceptive camouflage they rarely move and, in fact, stay even more still when startled, closing their yellow eyes and raising their substantial beak skywards, truly becoming one with the tree. They feed at night, eating everything from insects to snails; from frogs to lizards. Some prey, such as moths, they catch in flight, sometimes resulting in them being hit by cars while chasing insects illuminated in the headlights.

Tawnies mate for life. Our pair of Tawnies have a nest somewhere nearby, precariously made of sticks wedged in the fork of a tree, where the male sits on eggs during the day and the female shares incubation duties by night. After hatching the young are fed by both parents, and can develop half their adult weight in the month-long fledging period. The small Tawny we saw was most likely a fledgling, just learning to fly. How lucky are we in having this family share our backyard with us?

Tawny in Kevin and Glenys Murray backyard. Photo: Kevin Murray

In this LGA 103 Tawny Frogmouths have been rescued and 29 released in the June 2020 to June 2021 period. Collisions with motor vehicles and ‘unsuitable environment’ are listed as the primary reasons for the birds coming into care. Disease, listed as an ‘internal parasite’ is also listed.

Tawny frogmouths will often perch at the sides of roads where streetlights attract moths. Another reason to slow down on our local roads.

The tawny frogmouth (Podargus strigoides) is a species of frogmouth native to the Australian mainland and Tasmania and found throughout. It is a big-headed, stocky bird, often mistaken for an owl, due to its nocturnal habits and similar colouring, and sometimes, at least archaically, referred to as mopoke, a name also used for the Australian boobook, the call of which is often confused with that of the tawny frogmouth.

Tawny frogmouths are carnivorous and are considered to be among Australia's most effective pest-control birds, as their diet consists largely of species regarded as vermin or pests in houses, farms, and gardens. The bulk of their diet is composed of large nocturnal insects, such as moths, as well as spiders, worms, slugs, and snails but also includes a variety of bugs, beetles, wasps, ants, centipedes, millipedes, and scorpions. Large numbers of invertebrates are consumed to make up sufficient biomass, as are reptiles and frogs, and birds.

The conservation status of tawny frogmouths is "least concern" due to their widespread distribution. However, a number of ongoing threats to the health of the population are known. Many bird and mammalian carnivores are known to prey upon the tawny frogmouth. Native birds, including ravens, butcherbirds, and currawongs, may attempt to steal the protein-rich eggs to feed their own young. Birds of prey such as hobbies and falcons, as well as rodents and tree-climbing snakes, also cause major damage to the clutches by taking eggs and nestlings. In subtropical areas where food is available throughout the year, tawny frogmouths sometimes start brooding earlier in winter to avoid the awakening of snakes after brumation. Since 1998, a cluster of cases of neurological disease has occurred in tawny frogmouths in the Sydney area, caused by the parasite Angiostrongylus cantonensis, a rat lungworm.

Kayleigh Greig

Sydney Wildlife Rescue Carer

Red-Bellied Black Snake

What is your favourite local wildlife species?

One of my favourite animals here in Sydney has to be the Red-Bellied Black Snake.

Why do you like the Red-Bellied Black Snake?

I love red bellies because, as venomous creatures, they could pack a punch if they wanted to, but really they are very shy, gentle creatures. I remember seeing one swimming beside me while kayaking once and I couldn’t help but think how adorable it was, enjoying the sunshine and the water.

How long have seen or heard this animal?

Seeing a red belly is a rare treat and I’ve only seen them a few times in the wild, mostly while bushwalking. Of course, Mom has also rescued many over the years that I’ve been lucky enough to see!

Have you noticed any changes in the number of these animals in your local neighbourhood?

Red bellies are hard enough to spot in the first place because they like to keep to themselves, so it’s hard to tell how many are out there. I do know that as human territory continues to expand, snakes are increasingly hit on roads, caught in netting or find themselves having to get creative with their living spaces when there’s no bush left for them, so it’s more important than ever for people to be accepting of snakes in the garden, to keep providing safe habitat for them, and to appreciate the privilege of seeing such a fascinating and beautiful creature :)

Kayleigh with mum Lynleigh Greig, January 2023

There were 93 'front fanged' snakes rescued in the LGA during the 2020 to 2021 reporting period, of which 50 were released. Being attacked by cats lists highest as the cause, followed by 'unsuitable environment'. Unfortunately 'intentional harm by human' accrues at least 1 record, as does human interference. Entrapment and netting are also causes of impacts on front fanged snakes in our area.

Snakes are active when their body temperatures are between 28 and 31 °C . They also thermoregulate by basking in warm, sunny spots in the cool, early morning, possibly on roads, and rest in shade in the middle of hot days, and may reduce their activity in hot, dry weather in late Summer and Autumn.

Harmless Pythons were rescued 122 times in the same reporting period, with just 64 released. Although 'unsuitable environment' is listed highest as the cause for rescues, collisions with vehicles impacts these as well.

The red-bellied black snake (Pseudechis porphyriacus) is a species of venomous snake in the family Elapidae, indigenous to Australia. Originally described by George Shaw in 1794 as a species new to science, it is one of eastern Australia's most commonly encountered snakes. Averaging around 1.25 m (4 ft 1 in) in length, it has glossy black upperparts, bright red or orange flanks, and a pink or dull red belly. It is not aggressive and generally retreats from human encounters, but can attack if provoked. Although its venom can cause significant illness, no deaths have been recorded from its bite, which is less venomous than other Australian elapid snakes. The venom contains neurotoxins, myotoxins, and coagulants and has haemolytic properties. Victims can also lose their sense of smell.

Common in woodlands, forests, swamplands, along river banks and waterways the red-bellied black snake often ventures into nearby urban areas. It forages in bodies of shallow water, commonly with tangles of water plants and logs, where it hunts its main prey item, frogs, as well as fish, reptiles, and small mammals.

Red-bellied black snake. Photo: Oliver Neuman

The red-bellied black snake is generally not an aggressive species, typically withdrawing when approached. If provoked, it recoils into a striking stance as a threat, holding its head and front part of its body horizontally above the ground and widening and flattening its neck. It may bite as a last resort.

In Spring, male red-bellied black snakes often engage in ritualised combat for 2 to 30 minutes, even attacking other males already mating with females. They wrestle vigorously, but rarely bite, and engage in head-pushing contests, where each snake tries to push his opponent's head downward with his chin. The diet of red-bellied black snakes primarily consists of frogs, but they also prey on reptiles and small mammals. They also eat other snakes, commonly eastern brown snakes.

Bec Woods

Sydney Wildlife Rescue Carer

Eastern Water Dragon

What is your favourite local wildlife species?

Eastern Water Dragon (Intellagama lesueurii lesueurii)

Why do you like this animal/bird/reptile/aquatic species?

These friendly lizards are scattered throughout the northern beaches- I often see them along my favourite walking tracks near bodies of water, like Irrawong Reserve and Narrabeen Lake. They’re curious and friendly, and so beautiful to have in care. One of my most frequently rescued and cared for animals are water dragons- everything from tiny little babies through to big adult males (with their bright red chests).

How long have seen or heard this animal?

They’ve been around the area as long as I can remember!

Have you noticed any changes in the number of these animals in your local neighbourhood?

Unfortunately not everyone loves our local wildlife- I have noticed less young dragons in my local spots. Last year on Australia Day I was called to a rescue where a young couple had called our rescue hotline (Sydney Wildlife Rescue) with reports of water dragons who had darts sticking out of their bodies. Myself and other rescuers captured 2 dragons with darts (from a blow gun or similar) and lots of darts littered around the area. Disturbingly some darts were even homemade. The next few weeks were spent combing through the lake and bushland looking for more dragons, and often finding more darts. The incident was reported to the police and news channels, gaining lots of engagement and community outrage. This incident definitely further sparked my love for water dragons- so sad how cruel people can be.

There have been 390 Water Dragons rescued locally during the reported period of June 2013 to June 2021, 134 were released. In the data period of June 2020 to June 2021 72 were rescued and 31 released. Being attacked by dogs accounts, by far, for the highest 'common reason for rescue'. Unfortunately a dog will grab a water dragon around the neck and shake it from side to side violently, so even if they do not die from the bites and subsequent infections, their small bones have been fractured or dislocated beyond healing. The highest count for this locally occurred during the 2019 to 2021 timeframe - during the Covid lockdowns. In comparison, just two were lost due to car strikes.

Physignathus lesueurii lesueurii, the Eastern Water Dragon. Photographed in Careel Creek 31.10.2013. Picture by A J Guesdon.

Margaret Woods

Sydney Wildlife Rescue Carer

Owlet-Nightjar

What is your favourite local wildlife species?

Owlet- Nightjar

Who couldn’t love those big eyes and that cute whiskered face. They have a small bill and a wide gape, open mouth is as wide as their head. For such a little bird it has a rather large tail and a big presence.

This is the smallest Australian nocturnal bird. It is hard to spot as it is tiny, well camouflaged, nocturnal, and great at hiding. It will only be seen during the day if it looks out of a nesting hollow.

You would be lucky to see it at night even if you found its roost or it was out hunting. Their large brown eyes do not reflect light. They eat Insects. They catch them flying or jump on them on trees or on the ground.

I had been told by many other bird loving friends that they are living in the tree hollows around the northern beaches. Unfortunately, I hadn’t been able to spot one.

Why do you like the owlet nightjar?

I love all sorts of wildlife. I have photographed lots of wildlife especially birds over many years in our local area.

As a registered and trained volunteer with Sydney Wildlife Rescue my family and I have rescued and cared for a lot of injured, orphaned, or displaced wildlife over the past years.

I consider myself lucky to be a volunteer on the Sydney Wildlife Rescue Mobile Care Unit. My special role is to take photos of our patients for their vet records. Sometimes there is an opportunity that allows some beautiful photos, so I snap as many as possible.

Recently I had the absolute pleasure of seeing a gorgeous Owlet- Nightjar.

This patient was found on the ground and was rescued by a Sydney Wildlife Rescue volunteer carer. With concern about its condition, the carer made an appointment. Lucky for me I was there on the day it was examined by our volunteer vets.

How long have seen or heard this animal?

Only this once and I consider myself lucky to have such a chance to see one.

Have you noticed any changes in the number of these animals in your local neighbourhood?

I wish there were more. I think everyone would fall in love with them. We need more suitable tree hollows that they would live in but sadly with the rate of tree loss there will be less and less places for these little ones to live.

Apart from habitat loss the threats come from predators such as cats and fox that hunt and eat them.

.jpg?timestamp=1678540048345)

Margaret Woods at Aussie Ark, January 2023

Just 4 owlet-nightjars have been rescued locally with 1 released from 2013 to June 2021 and 298 recorded as rescued across the whole of NSW during the same time frames with 121 released. The low data numbers would, as Margaret states, be attributed to them rarely being seen. Cat attacks show as the highest cause of mortalities during the 2017 to 2019 years, however, ‘orphaned birds’ and ‘fallen from nest’ as well as ‘unsuitable environment’ showed up in the 49 rescued, 24 released stats for the 2020 to 2021 data. 2 were lost due to ‘human interference’.

The Australian owlet-nightjar (Aegotheles cristatus) is a nocturnal bird found in open woodland across Australia and in southern New Guinea. It is colloquially known as the moth owl.

The Australian owlet-nightjar feeds at night by diving from perches and snatching insects from the air, ground or off trunks and branches, in the manner of a flycatcher. It may also feed on the wing. It feeds on most insects, particularly beetles, grasshoppers and ants. During the day they roost in hollows in trees, partly for protection from predators and partly to avoid being mobbed by other birds that mistake them for owls.

The Australian owlet-nightjar nests mainly in holes in trees (or in other holes and crevices), which is provisioned with leaves by both of the pair. It is thought that the frequent addition of eucalyptus leaves is because they act as a beneficial insecticide. Three or four eggs are laid, and incubated by the female for just under a month. Both the adults feed the chicks, which fledge after a month. The young birds are reported to stay close to the parents for several months after they fledge.

Australian owlet-nightjar mainly nests in tree hollows. Photo: JJ Harrison

Hilary Green

The Greens, 2023 Candidate For Pittwater

The Butcher Bird

When the butcher birds herald the day with their clear, strong musical calls, I can’t help but wake up smiling. These clever little natives are rarely seen but often heard. They are so clever with their song - the Aboriginal name is Wadowadong. One of their tunes is Caw caw cooka cook. They mimic other birds and animals - even mobile phone rings and car alarms.

Hear and watch this amazing little fellow at his music making -

They are charming to see and hear, but they do butcher their prey. Feral pigeons, mice and rats are a treat for them, but alas, so are other small birds, lizards and insects. That’s wildlife!

They are very family oriented. The females build the nests and incubate their eggs. The males and other members of the groups forage for their supper.

Hilary with Butcher bird by Michael Fairweather

The chicks stay with their mother for about a year, and help nurture the next generation of chicks. Apparently, they squeak incessantly while following the mum around. Year-round, they live in the same territories, which they defend quite aggressively. They come in a variety of colours. Here are some pics from https://www.flickr.com/.

A demanding young Pied Butcherbird (ipost4u) Black Butcherbird (Chris Wiley)

Black backed Butcherbird (LiewMoiLoy Vincent) Silver-backed Butcherbird, Kakadu (Anne Collins)

Butcher birds are survivors. They can be found in a range of different habitats including arid, semi-arid and temperate zones, but are absent from the deserts and monsoon tropics. They have adapted well to city life. Hence, the butcher bird is not listed as vulnerable, or threatened, by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Sadly, 135 bird species in NSW, are either critically endangered, endangered or vulnerable, whilst 14 bird species in NSW have become extinct.

I have probably always heard these beautiful birdsongs, but they have only been brought to my attention in the last few years. And now I’m fascinated by them. They sing outside my window, all through the wetlands and forests, and can be heard any time during the day, but especially in the morning. They have been called the Break-o’-day-boy.

So, back to the music!

This, from the Pittwater Ecowarriors, will make you smile, I’m sure;

And so will this amazing duet, if you have time;

Susan Sorensen

Animal Justice Party, 2023 Candidate For Wakehurst

Wallaby

Wallabies die on Wakehurst Parkway

At a time when native wildlife need all the help they can get, it appears that wildlife corridors and native animal bushland homes are being sidelined. While the Lizard Rock development may be taken off the table for the time being, and is a monumental win for all who lobbied against its destruction, this is an election promise only at this stage and all other bushland at 5 other sites, as part of that original Development Delivery Plan approved, is still approved for development proposals - much of it surrounding the Wakerhurst Parkway and Narrabeen State park, where the roadside carnage of wildlife continues.

Susan Sorensen, the Animal Justice Party Candidate for Wakehurst states, ‘Native animals are being displaced and their habitats lost as a result of residential activity and roads having been built through their bushland homes. There have been 4 deceased Wallabies sighted on the Wakehurst Parkway by Animal Justice Party members in one month alone.’

The CSIRO states ‘a conservative estimate of 4 million Australian Mammals are killed each year on Australian Roads’. Insurance Australia estimates that '10 million animals are struck and killed by cars across Australia each year’. There are risks to humans also with 5% of fatal accidents relating to collisions with animals.

Susan says, ‘it is disheartening to see so many animals being hit by cars and left to die alone on the side of the road, often with a joey in pouch. We need renewed responsibilities for the relationships we humans have with animals, we need many more wildlife crossings and further education on safe dawn to dusk driving to save the lives of animals and humans alike.’

If elected at the state election on March 25, Susan will campaign for investment in mass trials of virtual fencing and more wildlife crossings such as green bridges, underpasses and exclusion fencing installed along roads built through bushland.

‘If we remain idle and do nothing at all without any protections put in place for our local native wildlife, we will soon become an area devoid of native animals.’

Susan Sorenson with an orphaned joey

The NSW Wildlife Rehabilitation dashboard states 89 wallabies and kangaroos were rescued in our area the period from June 2020 to June 2021 and just 10 released, with 5 of these being babies that had been rescued. Car collision is listed as the most common cause of death, although habitat alteration is also mentioned.

Since the records have been kept in 2013, 808 kangaroos and wallabies have been recorded as ‘rescued’ in this LGA and just 40 released. Collision with vehicle accounts for the bulk of the deaths and the Wakehurst Parkway and Mona Vale road are where these mortalities occur. Wallabies foraging at the sides of roads during the dusk and dawn and at night indicates these should be slow down, not speed up times, for humans residents.

There is also a growing number of red foxes being seen in our area, which will attack local wallabies. Local wildlife rescuers and carers saved one last year from being degloved by a fox and spent months caring for the attacked wallaby before it was healed enough to be realeased.

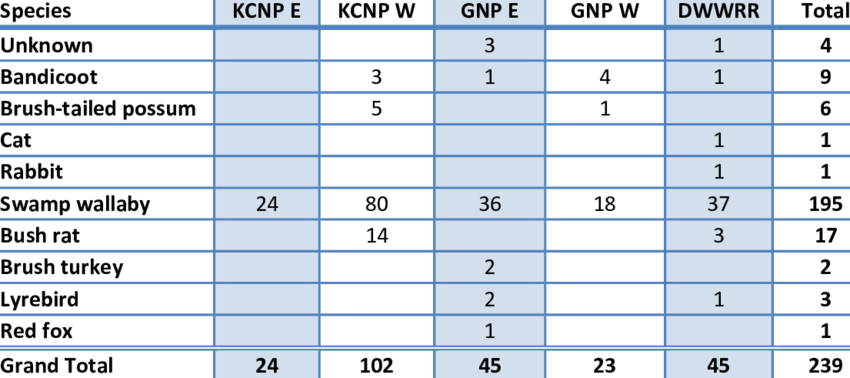

Number of individuals captured by cameras during the study across the study area, encompassing Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park (east and west), Garigal National Park (east and west) and the Dee Why West Recreation Reserve. From; Impact of roads on swamp wallaby populations on Sydney's Northern Beaches, August 2014. DOI:10.13140/2.1.4896.0640 Report number: Final report to the Roads and Maritime Services Affiliation: Centre for Compassionate Conservation, University of Technology, Sydney Authors: Daniel Ramp, University of Technology Sydney; Eric Dougherty, University of California, Berkeley; Gilad Bino, UNSW Sydney.

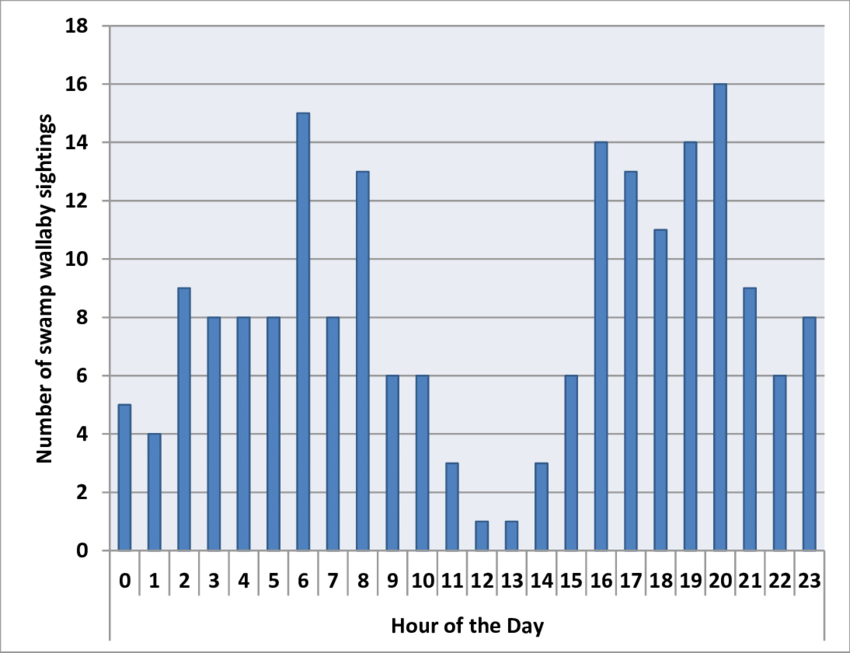

Number of wallaby sightings per hour sampled across all locations in the study area.

Some of our local wallabies are now also being listed as dying from disease. The Australian Registry of Wildlife Health has been investigating an emergent disease syndrome in swamp wallabies.

Initial reports were received from NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service Rangers that several swamp wallabies with erosive ear lesions were frequenting the camp grounds of Mimosa Rocks National Park on the NSW/QLD border. On visiting the area and surrounds Nov 2017, several swamp wallabies and a few red-neck wallabies were found to have eroded ears and cloudy corneas. One affected animal was emaciated and had a draining tract from a facial abscess (lumpy jaw), and it was euthanised on welfare grounds and to facilitate an investigation.

An unusual single celled parasite was found within the ear lesions of this animal and the organism is being further characterised.

Another swamp wallaby from Lovett Bay, Pittwater was more recently submitted for post mortem examination. The animal had severe corneal oedema (cloudy corneas), eroded ear margins, and a lacerated tongue suggestive of seizure activity. Impression smears of the ear lesions contained a similar single celled parasite to that seen in the Mimosa rocks animal.

They have also received reports of multiple swamp wallabies from Newport and Elvina Bay with neurological signs, but have not been able to follow that up to see if it is related.

So we seem to have something potentially new, that may have a fairly wide geographic range in NSW. Additional work is required to demonstrate that the parasite is causing the lesions, rather than just present in the blood of the wallabies.

They would be interested to examine additional animals that may be affected.

Please don’t hesitate to contact the Australian Registry of Wildlife Health if you have animals that you think might fit this syndrome.

Contact them on: Phone: 02 9978 4749 or 02 9978 4788 or Australian Registry of Wildlife Health

The Swamp Wallaby (Wallabia bicolor) or Black Wallaby is a small, stocky wallaby. They live in thick, forest undergrowth or sandstone heath. The swamp wallaby becomes reproductively fertile between 15 and 18 months of age, and can breed throughout the year. Gestation is from 33 to 38 days, leading to a single young. The young is carried in the pouch for 8 to 9 months, but will continue to suckle until about 15 months.

The swamp wallaby is typically a solitary animal, but often aggregates into groups when feeding. It will eat a wide range of food plants, depending on availability, including shrubs, pasture, agricultural crops, and native and exotic vegetation. It appears to be able to tolerate a variety of plants poisonous to many other animals, including brackens, hemlock and lantana.

The ideal diet appears to involve browsing on shrubs and bushes, rather than grazing on grasses. This is unusual in wallabies and other macropods, which typically prefer grazing. Tooth structure reflects this preference for browsing, with the shape of the molars differing from other wallabies. The fourth premolar is retained through life, and is shaped for cutting through coarse plant material.

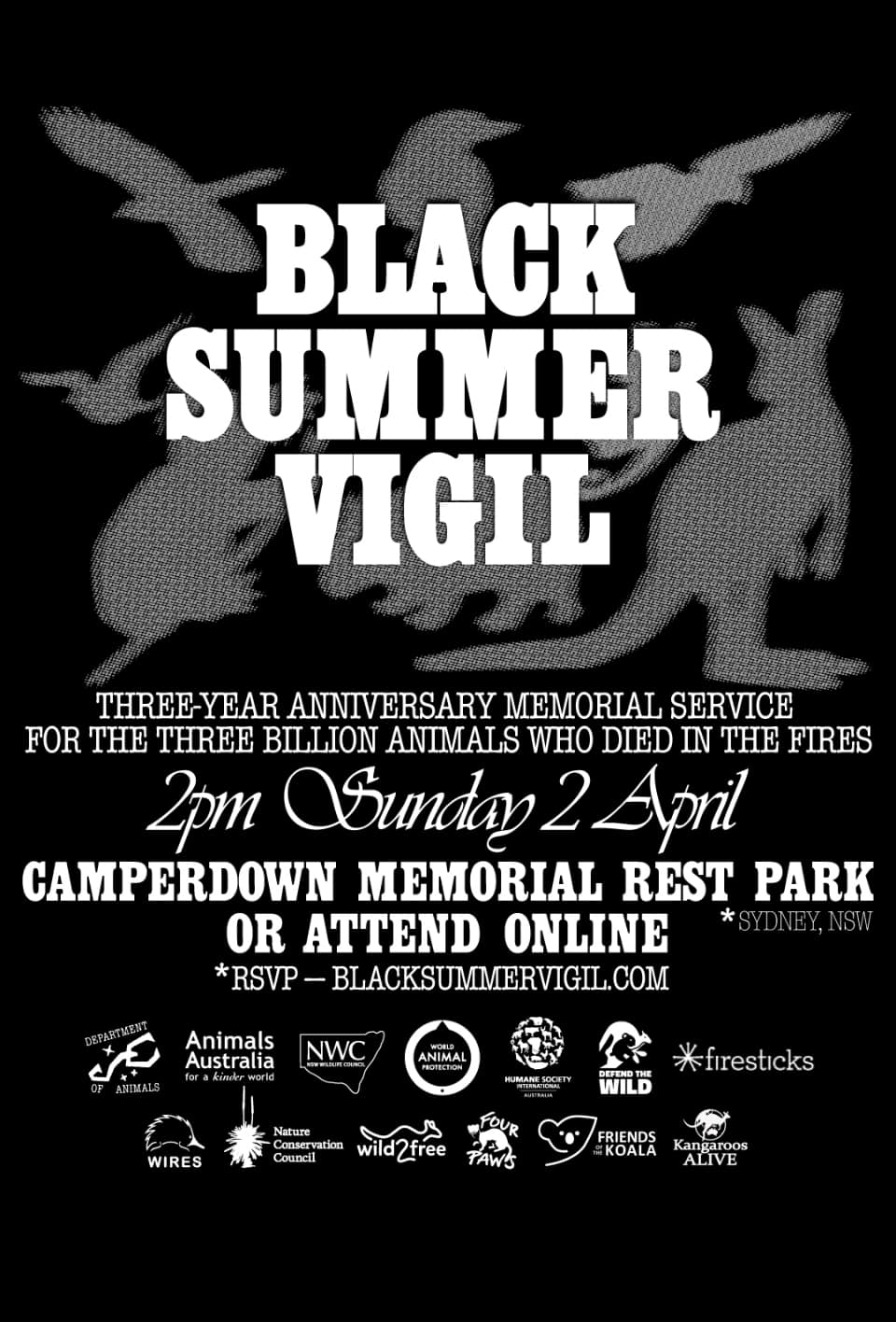

Black Summer Vigil For Wildlife

The New South Wales Wildlife Council invites all wildlife carers, wildlife vets, vet nurses, first responders and supporters to the upcoming Black Summer Vigil for Wildlife on Sunday April 2nd 2023 starting at 2pm.

Please join us for the Black Summer Vigil, a three-year anniversary memorial service for the three billion animals who lost their lives in the fires – “one of the worst wildlife disasters in modern history”.

Attend online or in-person at Camperdown Memorial Rest Park (Sydney).

RSVP at: blacksummervigil.com

You’ll hear personal stories from the NSW Wildlife Council, Southern Cross Wildlife Care and other first responders across wildlife rescue, rural fire service, photojournalism, Aboriginal custodianship, veterinary medicine, ecology and more.

+ Performance and Ceremony by Jannawi Dance Clan, sharing a Dharug cultural perspective to honour the Ancestors and bring the spirit of the animals into our midst.

Join us to honour the animals who perished – and in doing so, celebrate the unique and extraordinary wildlife of these lands.

Speakers include:

Greg Mullins, Former Commissioner, Fire and Rescue NSW; Climate Councillor and founder, Emergency Leaders for Climate Action. Greg warned Australia's then–Prime Minister in April 2019 that a bushfire catastrophe was coming. He pleaded for support and was ignored, then risked his life dealing with the ramifications on the ground. “You couldn’t see very far because of the orange smoke. Everything was dark. It was probably 2 o’clock in the afternoon but it was like night. Then I saw something moving on the side of the road and I walked closer. It was a mob of kangaroos. The speed of that fire with its pyroconvective storm driving it in every direction, they had nowhere to go. They came out of the forest, on fire, and dropped dead on the road. I’ve never seen that. Kangaroos know what to do in a fire. They’re fast animals. Climate change, driven by the burning of coal, oil, and gas is driving worsening bushfires across Australia, and putting our precious, irreplaceable wildlife in danger.”

Internationally recognised ecologist and WWF board member, Professor Christopher Dickman oversaw the work calculating the animal deaths from Black Summer. A Fellow of the Australian Academy of Science, Professor Dickman already wore the heavy task of being an ecologist during the sixth mass extinction, in the country that has the worst rate of mammalian extinction in the world. On 8 January 2020 media around the world shared his finding that Black Summer fires had killed one billion animals. Sadly, the fires continued for two more months, and his team's final count was three billion. This does not include invertebrates: it is estimated 240 trillion beetles, moths, spiders, yabbies and other invertebrates died in the fires.

Coming up from the South Coast, owner of Wild2Free Kangaroo Sanctuary Rae Harvey, as seen in The Bond and The Fire. She is in the sad position of having personally known and cared for a number of Black Summer's victims: many of the orphaned joeys she cared for were killed in the fires. (She nearly died herself too.) For three years, she has been unable to even speak their names. Now, for the first time, she will tell the story of the joeys she lost.

Cultural burning practitioner and Southern NSW Regional Coordinator with Firesticks Alliance, Djiringanj-Yuin Custodian Dan Morgan. Dan practises using Aboriginal knowledge to heal Country. He has worked for 18 years with the NSW National Parks & Wildlife Service and is on the board of management for the Biamanga National Park, a sacred area home to the last surviving koalas on the NSW south coast – which was partly destroyed by the fires of Black Summer. “The animals that live on our sacred sites are our Ancestors, it's our Cultural obligation to protect them. We have evolved with our Country over thousands of years, nourishing and protecting all living species. Our Country represents our people. So when the fires came, it was devastating to see the aftermath, and the feeling of helplessness was truly traumatising for our people, due to the denial of our Cultural right to manage Country as our Ancestors did for thousands of years prior to colonisation. Australia needs to make legislative changes that allow us to heal Country and our community through the fire knowledge and to stop incinerating ecosystems with destructive 'hazard-reduction' burns."

Head of Programs & Disaster Response at Humane Society International (HSI), Evan Quartermain was one of the first responders on Kangaroo Island where nearly 40% of the island burnt at high severity: “Those were some of the toughest scenes I’d ever witnessed as an animal rescuer: the bodies of charred animals as far as the eye can see. Every time we found an animal alive it felt like a miracle.” As a result of this firsthand experience, HSI commissioned a report into the state of Australia's disaster response for wildlife, which we'll also hear about.

+ More to come.

The Black Summer Vigil is brought to you by the Department of Animals, Animals Australia, the NSW Wildlife Council, World Animal Protection, Humane Society International and Defend the Wild, with support from WIRES, Firesticks Alliance, Nature Conservation Council of NSW, Wild2Free Kangaroo Rescue, Four Paws, Friends of the Koala and Kangaroos Alive.

More In:

- Ringtail Posse: 1 – February 2023; Anna Maria Monticelli: King Parrots/Water Dragons - Jacqui Scruby: Loggerhead Turtle - Lyn Millett OAM: Flying-Foxes - Kevin Murray: Our Backyard Frogs - Miranda Korzy: Brushtail Possums

- Ringtail Posse 2023: The Generation Witnessing An Extinction Of Urban Wildlife

- Motion To Have Fauna Management Plans In Local Council Comply With The NSW Code Of Practice For Injured, Sick And Orphaned Protected Fauna To Be Presented At LGNSW 2022 Conference - Some FMP's Passed Allow For Wildlife To Be Killed Where Their Homes Are Felled

- Spring Carnage For Our Wildlife: Out Of Date Data Shows At Least 4000 Local Rescues Annually - Lack Of 'Responsibility' Facilitates Extinctions

- Masked Lapwing Plover Chicks Were In Danger: Now They're Dead Because No One Is 'Responsible' For Wildlife In Council Areas

- Protected Water Dragons Targeted By Illegal Blow Darts In Warriewood: Disgraceful Cruel Act On Our Wildlife - Police Appeal For Information - January 2022

- Water Dragons Attacked By Blow-Darts At Warriewood Wetlands: Update - February 2022

- NSW Wildlife Rehabilitation dashboard: Wildlife rehabilitation data current to 30 June 2021. Retrieved from https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/topics/animals-and-plants/native-animals/rehabilitating-native-animals/wildlife-rehabilitation-reporting/wildlife-rehabilitation-data

Addresses To The October 2022 Council Meeting

by Birdlife Australia’s Urban Bird program coordinator, Dr Annie Naimo, and wildlife carer and retired toxicologist Edwina Laginestra

My name is Edwina Laginestra, I’m a local wildlife carer, and retired-scientist specialising in toxicology

Rodenticides – both first generation and second generation anti coagulants – are used to kill “pest rodents” but increasingly it is harming our wildlife. Especially in winter, many unwanted creatures come into our homes and other buildings for warmth and food. People see ratbait as an easy and out-of-mind solution but don’t generally think about other impacts. Our wildlife is affected both directly (as I have treated both brushtail possums and blue tongue lizards for ratbait) and indirectly (as predators such as raptors eat the baited rodents which are sick and an easy catch and have residual poison concentrations). Many pets are also affected. SGARs have been banned in other countries due to longevity in the environment.

Treating baited wildlife is horrific and most do NOT survive. Rodents take around 3 to 9 days to die, but animals with slower metabolisms, such as our marsupials, take longer. Regarding SGARs it takes 14 days for symptoms to show in a possum and 21 days for it to die (from NZ research). If we can get it early we have a chance and have to treat the possum for 6-8 weeks (volunteer carers pay for treatment, and vets may charge us at cost only). However, sometimes we do not know what we are dealing with and by the time the symptoms show it is too late. I have treated well over a dozen brushtail possums. I think only 3 survived – 2 were young and OK with treatment in captivity. One was an adult male who was in care for 3 months – ratbait treatment then physio and containment for regaining muscle strength. The Koagulon he was treated with cost $150. Often we get in a beautiful mum that has been baited and have to try and save the joey that may already be bleeding internally.

Earlier this year I picked up a beautiful barn owl that was sitting in the middle of Seaforth Oval – a dog had attacked it even though the owner was quick to realise what was happening. But the owl was now badly injured. Why could the dog attack it and break a wing and pelvis? Because it was already unwell with eating baited rodents. What an horrific end of life. We have been picking up boobooks and Tawny Frogmouths that were likely baited but it is only recently there has been funding to test for harmful chemicals.

I have also picked up many ringtail possums that have eaten tips of freshly sprayed hedges. They foam at the mouth and spin as they die (which can take more than 8 hours). I spoke to Yates about systemic treatments in some plants for psyllids. They felt the poison may be active within the plant (and leaves) for up to 6 months. So although ringtail possums rarely take SGARs, they are very vulnerable to herbicides. However yesterday I had a ringtail die suddenly – he’d been in care for 5 days, but suddenly he was very thirsty and dizzy. I administered fluids and antibiotics (as he’d had surgery) but he died with blood coming out of his nose, paws and abdomen. He was probably already dying for a week before coming into care. He may have eaten bait due to habitat and food loss.

Photo: brushtail joey un-emerged rodenticide, image supplied

Wildlife carers are the volunteers that spend most money on their volunteering. We also already have quite a number of patients already in care. Giving drugs and physio adds extra time to our care load. We also spend time taking them to the vet who are also pressed for time and often treat wildlife for free. Sometimes we simply do not know what we are dealing with and administer treatment too late or incorrectly and we can make symptoms worse. This causes great anxiety as well. If there are actions others can take to avoid wildlife coming into care that would be most helpful – regarding pest management there are many other options in the cities – including the natural pest management our wildlife provides. Watching an animal get worse and die in care is tough emotionally and physically.

Barn Owl that died from Ratbait secondary poisoning. Image supplied

Dr Annie Naimo, Urban Bird Program Coordinator, BirdLife Australia

I’m writing on behalf of BirdLife Australia to support your motion to phase out the use of Second-generation Anticoagulant Rodenticides (SGARs).

BirdLife Australia is an independent non-partisan science-based bird conservation charity with over 300,000 supporters. Our primary objective is to conserve and protect Australia’s native birds and their habitat. We are the national partner of BirdLife International, the world’s largest conservation partnership.

Second-generation anticoagulants pose an extreme threat to native birds and wildlife. SGARs take several days to kill pests, and in this time accumulate in the body of poisoned animals.

SGARs persist in the body for a long duration, and in carcasses after death- posing additional risk to wildlife that may prey upon poisoned animals.

In greater Sydney, research undertaken by BirdLife Australia has found fatal levels of SGARs in dead Powerful Owls, a vulnerable species. Further Australian studies have shown similar fatal levels of SGARs in other birds of prey, such as Southern Boobooks and Wedge-tailed Eagles.

Other Australian wildlife are also at risk and have had documented instances of SGAR poisoning, including marsupials, native rodents, and reptiles, as well as pet cats and dogs.

Because of the clear evidence and risks, SGARs have been heavily regulated in Europe, Canada, and the USA. Many other local governments areas in NSW are already phasing out SGARs in their community, including Randwick, Wollongong, Tweed Shire, Port Macquarie-Hastings and Kiama.

Importantly, there are alternative pest control products available (e.g. first-generation anticoagulant rodenticides, non-anticoagulant rodenticides including cholecalciferol) that are similarly as effective as SGARs, but pose significantly less environmental risk when administered correctly.

To support you in your transition away from SGARs, BirdLife Australia has developed an Action Kit for Councils.

The Action Kit details how SGARs threaten wildlife and pets, provides effective ways that councils can move to alternative pest control methods, and includes links to additional resources to help you to keep your local community safe.

Rat Poisons Are Killing Our Wildlife: Alternatives

BirdLife Australia is currently running a campaign highlighting the devastation being caused by poison to our wildlife. Rodentcides are an acknowledged but under-researched source of threat to many Aussie birds. If you missed BirdLife's rodenticide talk but would like to know more, share data and comment on the use of rodenticides in Australia please visit: https://www.actforbirds.org/ratpoison

Owls, kites and other birds of prey are dying from eating rats and mice that have ingested Second Generation rodent poisons. These household products – including Talon, Fast Action RatSak and The Big Cheese Fast Action brand rat and mice bait – have been banned from general public sale in the US, Canada and EU, but are available from supermarkets throughout Australia.

Australia is reviewing the use of these dangerous chemicals right now and you can make a submission to help get them off supermarket shelves and make sure only licenced operators can use them.

There are alternatives for household rodent control – find out more about the impacts of rat poison on our birds of prey and what you can do at the link above and by reading the information below.

Let’s get rat poison out of bird food chains.

Powerful Owl at Clareville - photo by Paul Wheeler

Pesticides that are designed to control pests such as mice and rats cane also kill our wildlife through either primary or secondary poisoning. Insecticides include pesticides (substances used to kill insects), rodenticides (substances used to kill rodents, such as rat poison), molluscicides (substances used to kill molluscs, such as snail baits), and herbicides (substances used to kill weeds).

Primary poisoning occurs when an animal ingests a pesticide directly – for example, a brushtail possum or antechinus eating rat bait. Secondary poisoning occurs when an animal eats another animal that has itself ingested a pesticide – for example, a greater sooty owl eating a rate that has been poisoned or an antechinus that had eaten rat bait.

Rodenticides are the most common and harmful pesticides to Australian wildlife. Though no comprehensive monitoring of non-target exposure of rodenticides has been conducted, numerous studies have documented the harm rodenticides do to native animals. In 2018, an Australian study found that anticoagulant rodenticides in particular are implicated in non-target wildlife poisoning in Australia, and warned Australia’s usage patterns and lax regulations “may increase the risk of non-target poisoning”.

Most rodenticides work by disrupting the normal coagulation (blood clotting) process, and are classified as either “first generation” / “multiple dose” or “second generation” / “single dose”, depending on how many doses are required for the poison to be lethal.

These anticoagulant rodenticides cause victims of anticoagulant rodenticides to suffer greatly before dying, as they work by inhibiting Vitamin K in the body, therefore disrupting the normal coagulation process. This results in poisoned animals suffering from uncontrolled bleeding or haemorrhaging, either spontaneously or from cuts or scratches. In the case of internally haemorrhaging, which is difficult to spot, the only sign of poisoning is that the animal is weak, or (occasionally) bleeding from the nose or mouth. Affected wildlife are also more likely to crash into structures and vehicles, and be killed by predators.

An animal has to eat a first generation rodenticide (e.g. warfarin, pindone, chlorophaninone, diphacinone) more than once in order to obtain a lethal dose. For this reason, second generation rodenticides (e.g. difenacoum, brodifacoum, bromadiolone and difethialone) are the most commonly used rodenticides. Second generation rodenticides only require a single dose to be consumed in order to be lethal, yet kill the animal slowly, meaning the animal keeps coming back. This results in the animal consuming many times more poison than a single lethal dose over the multiple days it takes them to die, during which time they are easy but lethal prey to predators. This is why second generation poisons tend to be much more acutely toxic to non-target wildlife, as they are much more likely to bioaccumulate and biomagnify, and clear very slowly from the body.

Species most at risk from poisons

Small Mammals

Small mammals including possums and bandicoots often consume poisons such as snail bait, or rat bait that has been laid out to attract and kill rats, mice, and rabbits. Poisons such as pindone are often added to oats or carrots, and lead to a slow, painful death of internal bleeding. Australian possums often consume rat bait such as warfarin, which causes extensive internal bleeding, usually resulting in death.

There is a very poor chance of survival. Possums are also known to consume slug bait, which results in a prolonged painful death mainly from neurological effects. There is no treatment.

Small mammals can also be poisoned by insecticides. Possums, for example, can ingest these poisons when consuming fruit from a tree that has been sprayed with insecticide. Rescued by a WIRES carer, the brushtail possum joey pictured below was suffering from suspected insecticide poisoning. Though coughing up blood, luckily the joey did not ingest a lethal dose as he survived in care and was later released.

Large Mammals

Despite their size, large mammals including wallabies, kangaroos and wombats can also fall victim to pesticide poisoning. Wallabies and kangaroos have been known to suffer from rodenticide poisoning, while poisons often ingested by wombats include rat bait from farm sheds, and sodium fluroacetate (1080) laid out to kill pests such as cats and foxes.

Australian mammals are also impacted by the use of insecticides. DDT, although a banned substance, has been reported as killing marsupials.

Birds

Birds have a high metabolic rate and therefore succumb quickly to poisons. Australian birds of prey – owls (such as the southern boobook) and diurnal raptors (such as kestrels) – can be killed by internal bleeding when they eat rodents that have ingested rat bait. A 2018 Western Australian study determined that 73% of southern boobook owls found dead or were found to have anticoagulant rodenticides in their systems, and that raptors with larger home ranges and more mammal-based diets may be at a greater risk of anticoagulant rodenticide exposure.

Insectivorous birds will often eat insects sprayed with insecticides, and a few different species of birds may be affected at the same time. Unfortunately little can be done and death most often results.

Organophosphates are the most widely used insecticide in Australia. Birds are very susceptible to organophosphates, which are nerve toxins that damage the nervous system, with poisoning occurring through the skin, inhalation, and ingestion. Organophosphates can cause secondary poisoning in wild birds which ingest sprayed insects. Often various species of insectivorous birds are affected at the same time as they come down to eat the dying insects. After a bird is poisoned, death usually occurs rapidly. Raptors have also been deliberately or inadvertently poisoned when organophosphates have been applied to a carcass to poison crows.

Organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) are persistent, bio-accumulative pesticides that include DDT, dieldrin, heptachlor and chlordane. OPC’s have been used extensively in the agriculture industry since the 1940s. Some of the more common product names include Hortico Dieldrin Dust, Shell Dieldrex and Yates Garden Dust. Although no OCP’s are currently registered for use in the home environment in Australia, many of these products still remain in use on farms, in business premises and households. OCP poisons remain highly toxic in the environment for many years impacting on humans, animals, birds and especially aquatic life. They can have serious short-term and long-term impacts at low concentrations. In addition, non-lethal effects such as immune system and reproductive damage of some of these pesticides may also be significant. Birds are particularly sensitive to these pesticides, and there have even been occasions where the deliberate poisoning of birds has occurred. Tawny frogmouths are most often poisoned with OCP’s. The poisons are stored in fat deposits and gradually increase over time. At times of food scarcity, or during any stressful period, such as breeding season or any changes to their environment, the fat stores are metabolised, and with it, the poison load in their blood streams reaches acute levels, causing death.

Although herbicides, or weed killers, are designed to kill plants, some are toxic to birds. Common herbicide glyphosate (Roundup) will cause severe eye irritation in birds if they come into contact with the spray. Herbicides also have the impact of removing food plants that birds, or their insect food supply, rely on. Birds can also readily fall victim to snail baits, either via primary or secondary poisoning.

Reptiles and Amphibians

As vertebrate species, reptiles and amphibians are also at risk of pesticides. Though less is known about the effects of pesticides on reptiles and amphibians, these animals have been known to fall victim to pesticide poisoning. Blue-tongue lizards, for example, often consume rat bait and die of internal bleeding. A 2018 Australian study also found that reptiles may be important vectors (transporters) of rodenticides in Australia.

How to keep pests away and keep wildlife safe

Remember, pesticides are formulated to be tasty and alluring to the target species, but other species find them enticing, too. It is safest for wildlife, pets and people for us to not use any pesticides, and prevent or deter the presence of pests practically, rather than attempt to eliminate them chemically.

Tips to prevent and deter wildlife deaths from poisoning:

- Deter rats and mice around your property by simply cleaning up; removing rubbish, keeping animal feed well contained and indoors, picking up fallen fruits and vegetation, and using chicken feeders removes potential food sources.

- Seal up holes and in your walls and roof to reduce the amount of rodent-friendly habitat in your house.

- Replace palms with native trees; palm trees are a favourite hideout for black rats, while native trees provide ideal habitat for native predators like owls and hawks which help to control rodent populations.

- Set traps with care in a safe, covered spot, away from the reach of children, pets and wildlife. Two of the most effective yet safe baits are peanut butter and pumpkin seeds.

- To control slugs, terracotta or ceramic plant pots can be placed upside down in the garden or aviary. Slugs and snails will seek the dark, damp area this creates, and can be collected daily. They can then be drowned in a jar of soapy water. You can also sink a jar or dish into the soil and fill it with beer. The slugs are attracted to the yeast in the beer, fall in and then drown.

Poisons kill dogs too

Because of their poisonous nature, pesticides pose a risk to animals and people alike, including pets and children. Roaming pets like cats and dogs are most at risk of being poisoned, with one 2016 study at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences finding that one in five dogs had rat poison in its body, and a 2011 study by the Humane Society in the United States finding that 74% of their pet poisoning cases are due to second-generation anticoagulants such as rat baits.

It is best to avoid the use of all pesticides, or otherwise use them sparingly, carefully and only after researching each poison and its correct usage. Always supervise pets and children, keep poisons locked out of their reach, and be vigilant in public spaces where pesticides may have accumulated, e.g. poisons can accumulate in streams or puddles where herbicides have recently been sprayed.

If you suspect your pet has been poisoned, seek veterinary help immediately.

If you suspect your child or another adult has been poisoned, do not induce vomiting and call the NSW Poisons Information Centre on 13 11 26 for 24/7 medical advice, Australia-wide.

References

Lohr, M. T. & Davis, R. A. 2018, Anticoagulant rodenticide use, non-target impacts and regulation: A case study from Australia, Science of The Total Environment, vol. 634, pp. 1372-1384.

Lohr, M. T. 2018, Anticoagulant rodenticide exposure in an Australian predatory bird increases with proximity to developed habitat, Science of The Total Environment, Volume 643, pp.134-144.

Lohr, M. T. 2018, Anticoagulant Rodenticides: Implications for Wildlife Rehabilitation, conference paper, Australian Wildlife Rehabiliation Conference, awrc.org.au

Olerud, S., Pedersen, J. & Kull, E. P. 2009, Prevalence of superwarfarins in dogs – a survey of background levels in liver samples of autopsied dogs. Norwegian University of Life Sciences, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and Life Sciences, Department of Sports and Family Animal Medicine, Section for Small Animal Diseases.

Healthy Wildlife, Healthy Lives, 2017, Rodenticides and Wildlife, healthywildlife.com.au

Society for the Preservation of Raptors Inc. 2019, Raptor Fact Sheet: Eliminate Rats and Mice, Not Wildlife!, raptor.org.au/factsheetpests.pdf

W.I.R.E.S. Poisons and baits don't just kill rats.

.jpg?timestamp=1590728675788)

Barking Owl (Ninox connivens connivens)- photo by Julie Edgley - this nocturnal animal will eat mice and so become a victim of poisons through them