Councils Approving DA's in Known Flood Zones - NSW Government's Proposed Climate Change and Natural Hazards State Environmental Planning Policy (SEPP): Have Your Say + Emergency Services Levy reform

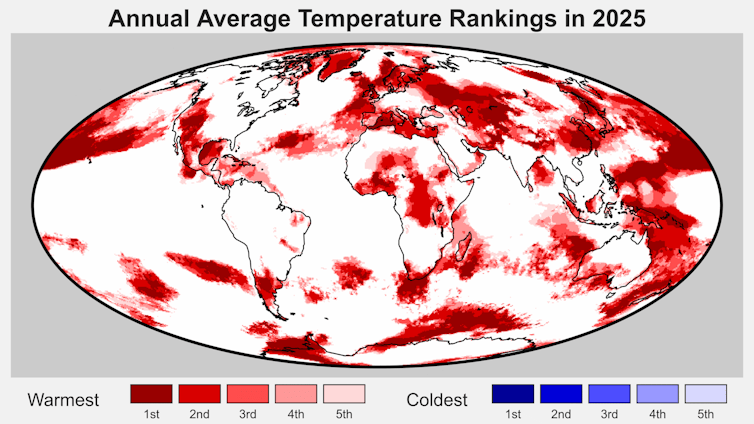

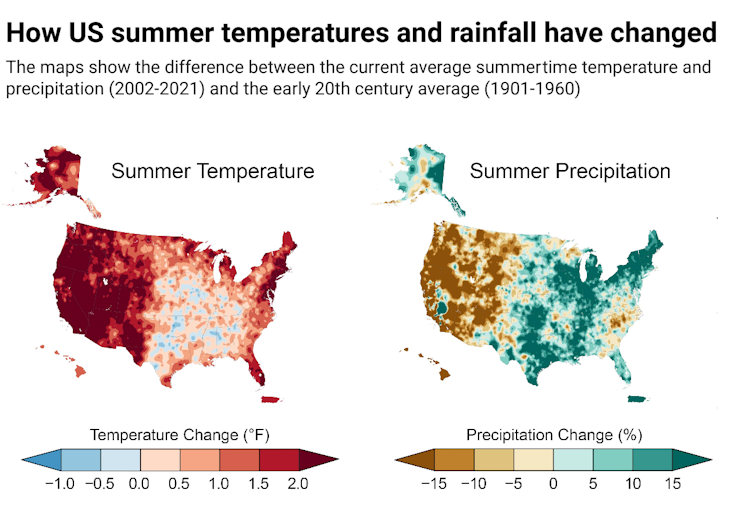

On Tuesday February 17 2026 the Minns Government announced it is 'further streamlining planning approvals, while making sure new homes and infrastructure are built to better withstand the extreme weather impacts and natural disasters caused by climate change'. The government stated this while announcing it is seeking feedback on the 'Climate Change and Natural Hazards SEPP' until March 17 2026.

Local and state environment groups state the Climate Change and Natural Hazards SEPP supports more buildings to go in areas that should not be built in, which creates more hazards and greater impact again on the natural environment.

Concurrently, the government has opened feedback until February 27 on its Draft Sydney Plan, where, once again, not destroying the environment is not a high priority. In fact it is listed as 5th out of 7 Priorities. This was made available December 12 2025, when most people had clocked off for the year. Visit: www.planningportal.nsw.gov.au/draftplans/exhibition/sydney-plan

This had been preceded by a Sunday February 15 announcement on the State Government's 'Next steps for Emergency Services Levy reform' which reads as though those who chose not to build on a floodplain (or the sand), or in a bushfire zone, via approved state government legislation, or 'supported' by councils development proposals, can now pick up the tab for these decades of government policies and councils decisions, some of which continue being approved to the present day, for those who did buy into such properties.

The Emergency Services Levy (ESL) in NSW is a charge on insurance policies and local council rates used to fund roughly 85% of the operating budgets for critical emergency services. It primarily supports Fire and Rescue NSW, the NSW Rural Fire Service (RFS), and the NSW State Emergency Service (SES).

The NSW Government collects the majority of the ESL (about three-quarters) through insurance companies, which add it to home, contents, and commercial property insurance policies.

While the levy is not directly charged to residents on rate notices, local councils are required to contribute 11.7% of the total cost of NSW emergency services, so ratepayers are funding it. By May 1 2024 the NB council stated its Emergency Services Levy had increased to $9.3 million, the equivalent of $90 per ratepayer.

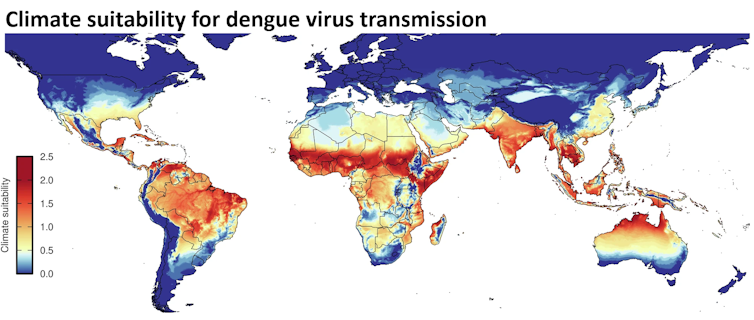

Major Australian insurers have been restricting or pausing the sale of new home insurance policies in specific high-risk, flood-prone, and bushfire-prone areas, particularly in Queensland and New South Wales. This is part of a broader industry trend where insurers are managing their exposure to risk following an increased frequency of natural disaster events.

Suncorp, one of those major insurers, has cited the need for improved flood mitigation infrastructure from local and state governments and the high cost of claims, often stating they cannot provide coverage in areas prone to repeated damage.

The released statement reads:

'Options to reduce household insurance costs and fix an unfair funding model for emergency services will be put to a NSW parliamentary inquiry.

While emergency services benefit everyone, most of their funding comes from a levy not everyone pays. The Minns Labor Government is committed to removing this Emergency Services Levy (ESL) and replacing it with a simple and transparent levy spread across all properties.

Currently, the burden of paying the ESL is unfairly placed only on those who take out property insurance. The cost of this levy for residential insurance has increased 48% from 2017-18 to 2023-24, adding pressure on household budgets.

All mainland states, apart from NSW, have implemented property-based levies to fund their emergency services.

In November 2023, the Minns Labor Government committed to reforming the ESL. The parliamentary inquiry will build on extensive public consultation carried out since then, and seeks to develop a consensus and strengthen support for the reform’s direction.

To inform the inquiry process, the Government will release an options paper which includes five levy model options. This follows a comprehensive collection of property level insurance policy data and land classifications performed by local councils under legislative amendments.

The Government thanks the insurance industry and local councils for their cooperation with this critical exercise for modelling reform options.

In designing the reform, the Government is also committed to protecting pensioners and vulnerable members of the community and ensuring a revenue-neutral model for sustainably funding emergency services agencies.

This is part of the Minns Labor Government’s commitment to cut red tape, remove unnecessary duplication across government and ease cost-of-living pressures on NSW households.'

Treasurer Daniel Mookhey said:

“This is an important step in moving funding for emergency services to an equitable and sustainable footing that cuts the cost of insurance. The parliamentary inquiry will provide an open and transparent forum to test the proposed framework and ensure stakeholder perspectives are meaningfully considered.

“We want to work with the Opposition and the crossbench to plot the last leg of this journey. This system funds services that protect all of us – and it is time for all politicians to work together to reform it.”

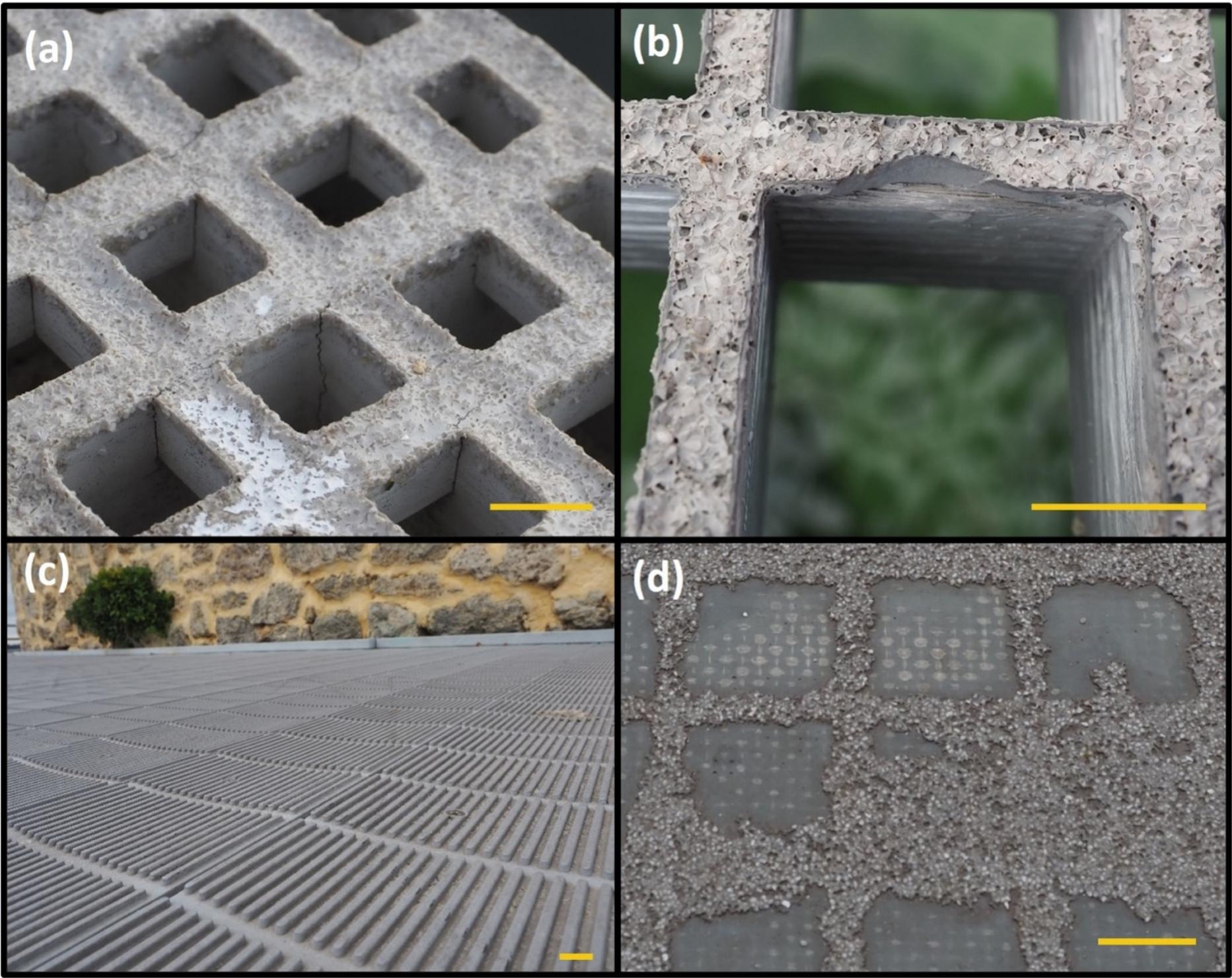

DA's in Flood Zones-Floodplains-Bushfire Zones being 'supported' - Approved

The insurance industry has urged the government to strongly consider climate risks and natural hazards in planning approvals to avoid future financial exposure.

While there have been moves to restrict development in the most dangerous areas, new projects continue to be approved in flood-prone regions, and on mapped floodplains, including in Pittwater.

The NSW Government has stated it is 'navigating a complex balance between addressing an acute housing shortage and managing the high risks associated with building on floodplains', particularly in Western Sydney and the Northern Rivers.

Despite stating on 29 October 2023:

'The NSW Government is delivering on its election commitment to no longer develop housing on high-risk flood plains in Western Sydney. The Government is today announcing it has rezoned parts of the North-West Growth corridor to ensure NSW does not construct new homes in high-risk areas. The Government is also releasing the Flood Evacuation Modelling report for the Hawkesbury-Nepean Valley, which informed the rezoning decisions.' Report is a PDF- 6.3MB

Earlier this month the NSW government green-lit almost 1000 new homes for a flood-prone north-western Sydney suburb. The proposed development at Marsden Park North, comprising 960 homes, is in the Hawkesbury-Nepean Valley, considered by the state government to have Australia’s highest unmitigated flood risk exposure.

Residents state the developers are in charge and the state government and local councils simply work to facilitate their proposals, which will pass the costs of future mitigation on to residents. Councils are charged with ignoring the still in place Development Control Plans for proposals in and on known flood zones, floodplains and in bushfire zones.

The 2023 NSW Government 'Flood risk management manual-The policy and manual for the management of flood liable land', states:

In regards to 'Your council's role' the state government says

'Your local council has 2 key responsibilities:'

- They carry out studies to understand flood risk, examine options to manage it, and keep the community informed about flooding, supporting emergency management planning.

- They take flooding into account when controlling the development of flood-prone land and in carrying out management actions, such as the investigation, design, construction, operation and maintenance of flood mitigation works.

The same document ensures councils that support DAs in flood zones cannot be sued afterwards, stating:

Section 733 of the Local Government Act 1993 provides local councils and statutory bodies representing the Crown, and their employees, with a limited legal indemnity for certain advice given, or things done or not done, relating to the likelihood of flooding or the extent of flooding

While DA's being lodged for these zones are progressed by councils, and lead to those who must deal with the impacts, and added costs - such as the seawall at Collaroy the forced amalgamation of all three councils has made the financial burden of everyone across the LGA - a belief by those who have objected to such projects being approved, is residents knowledges is ignored and they have been treated with contempt by the councils that 'support' these proposals before, during, and after they have 'worked with' developers to pass them.

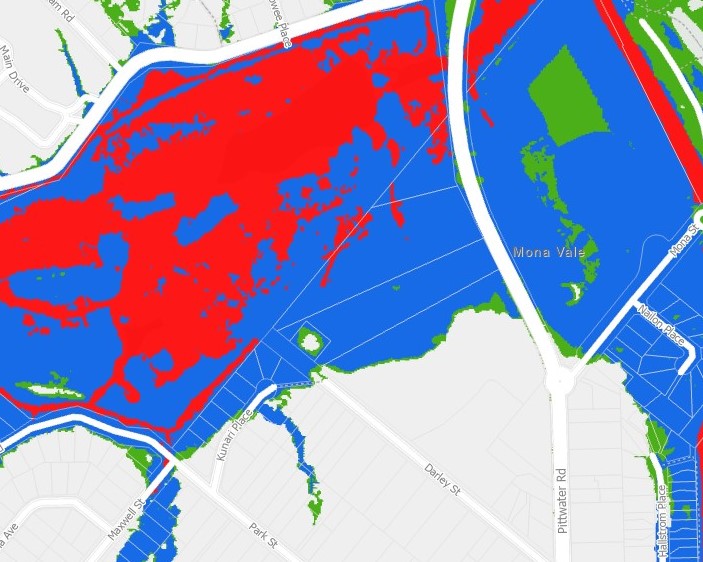

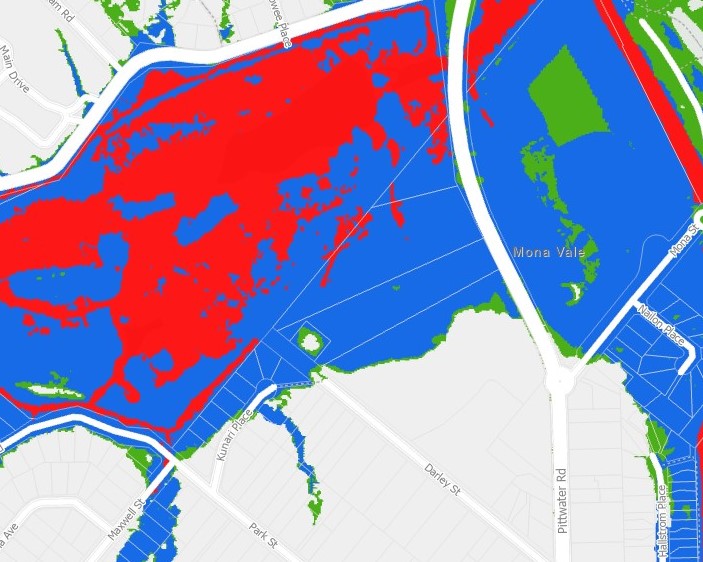

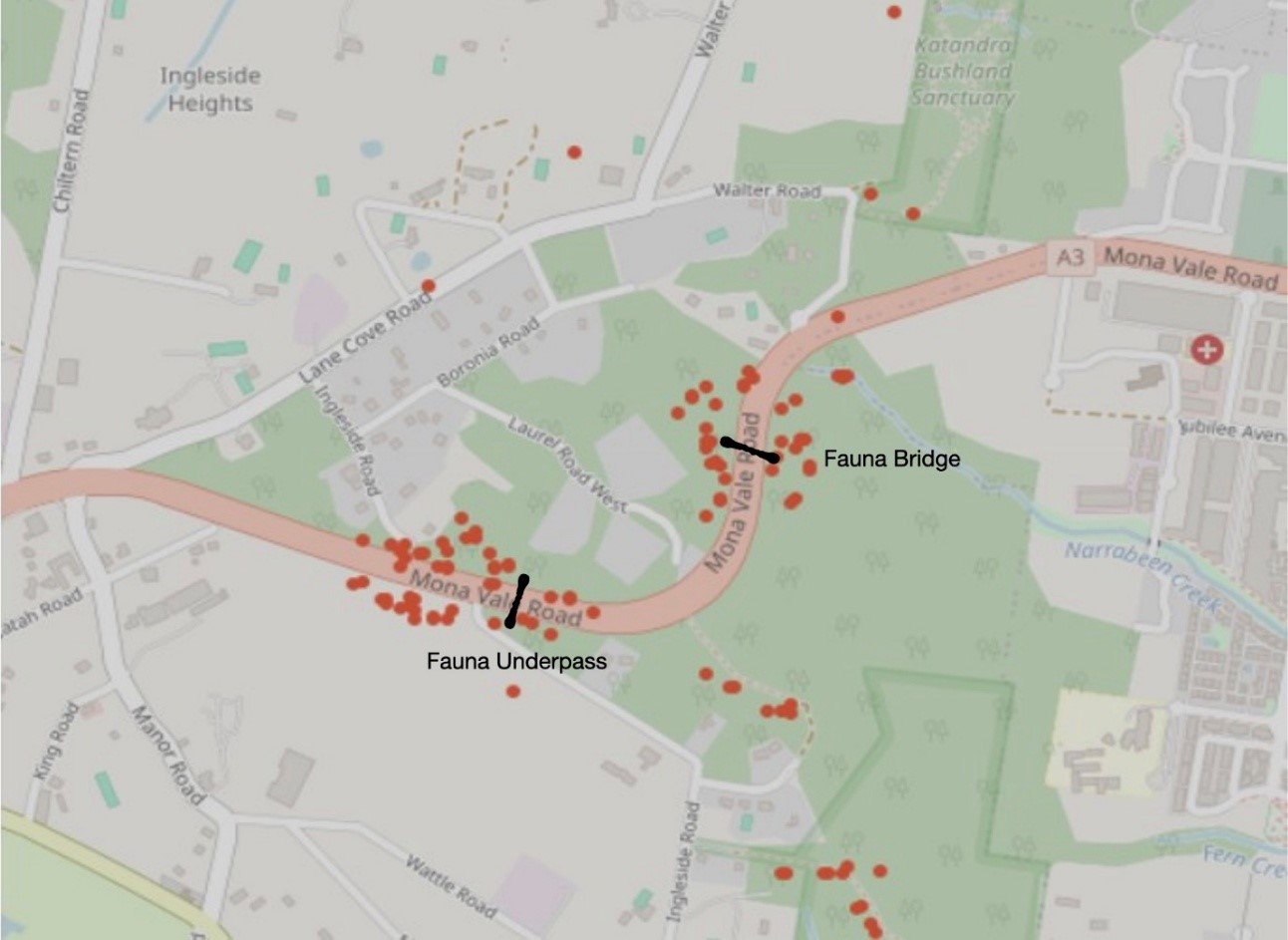

One local example is the council supporting construction of a 4-storey residential flat building with a 2 level basement on the corner of Kunari Place and Park Street, Mona Vale.

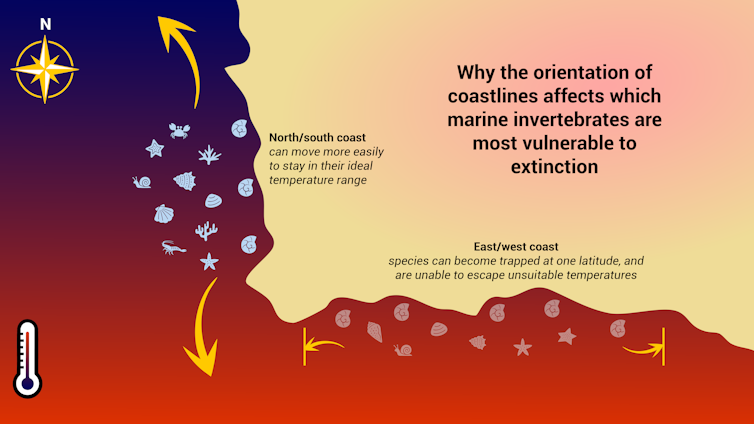

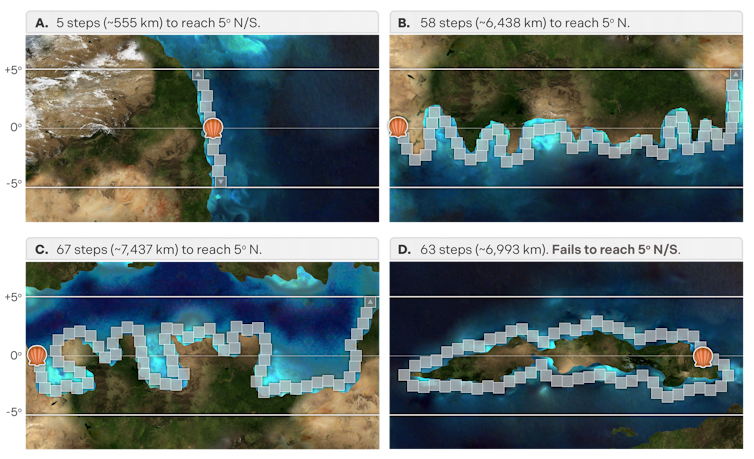

Overland flooding, especially in areas or as part of a known flood-affected area zone can be exacerbated by installing structures into the earth, and through their channels - disrupting the flows.

Underground carparks significantly alter local hydrology by acting as large, impermeable barriers that force surrounding groundwater to move around or underneath them. As urban development covers natural, porous ground, stormwater and groundwater cannot flow freely, causing the soil to saturate and exert intense "hydrostatic pressure" on the underground structure.

Because the concrete structure is impermeable, water that would naturally percolate through the soil is instead forced to move through the remaining surrounding earth, impacting those 'downstream' or around the property.

Due to being below the water table, these structures are highly susceptible to flooding from rising groundwater or runoff entering via ramps.

This DA went to the Land and Environment court with the February 6 2026 Decision by Acting Commissioner of the Court, G Kullen’s Judgement noting:

A signed s 34 agreement with Annexure A and the amended plans were filed with the Court on 25 November 2025. A set of corrected conditions of consent was filed with the Court on 15 December 2025. The s 34 agreement is supported by an agreed statement of jurisdictional prerequisites.

Under s 34(3) of the LEC Act, I must dispose of the proceedings in accordance with the parties’ decision if the parties’ decision is a decision that the Court could have made in the proper exercise of its functions. In making the orders to give effect to the agreement between the parties, I was not required to, and have not, made any merit assessment of the issues that were originally in dispute between the parties.

The parties’ decision involves the Court exercising the function under s 4.16 of the EPA Act to grant consent to the DA.

Those who had objected to this DA were not provided with any of the amended plans or conditions of consent.

Additionally, the DA was made in reliance upon Chs 2 and 6 of State Environmental Planning Policy (Housing) 2021 (Housing SEPP) and proposes that 5 apartments be used for the purposes of affordable housing.

The five apartments are one-bedders of very small size, what others would term 'bed-sits', at the back of the development.

Under this scheme the Height of Buildings may be increased if such 'affordable housing' is included.

Pursuant to cl 4.3 of LEP 2014, the Site is subject to an 8.5m HOB (Height of Building) control. However, s 179(2)(e) of the Housing SEPP prescribes a non-discretionary development standard of 9.5m - which was applied atop that LEP HOB.

The parties (developer and the NB council) then advised the court that:

Section 16(3) of the Housing SEPP permits an additional building height equal to the percentage of additional FSR available under s 16(1) of the Housing SEPP. As the proposed development achieves the full 30% FSR incentive, the maximum permissible building height increases by 30%, resulting in a maximum building height of 12.35m.

Another 4 metres over the Pittwater Council LEP equates to another storey on these buildings.

The NSW Government Planning Department stated last year:

'Further amendments were made on 14 February 2025 to uphold the original policy intent of the in-fill affordable housing provisions. Developments seeking in-fill affordable housing bonuses can only use a local bonus if it meets relevant LEP provisions. The bonuses, unless otherwise specified, do not override or remove the requirement to comply with any land and development controls that apply. No other amendments were made.'

The now passed DA also approves the removal of 24 trees from the property.

An October 2025 published report out of the University of Sydney states: 'The chance of large-scale flooding in a specific catchment area can increase by as much as eight-fold if widespread deforestation has occurred.'

“Australia, and the rest of the world, must wake up to the new dangers floods are posing. These dangers will only increase as warming intensifies, bushfires become more frequent, and storms larger as the atmosphere holds more moisture than before.” - Professor Lucy Marshall, School of Civil Engineering, said

In assessing the proposal prior to the Land and Environment judgment the council, in its 'Natural Environment Referral Response - Flood', stated:

‘’This proposal is for the demolition of existing dwellings across three lots and the construction of two, four-story apartments. The proposal is assessed against Section B3.11 of the Pittwater DCP and Clause 5.21 of the Pittwater LEP. The proposal is located outside of the Flood Planning Precinct and is not subject to flood-related development controls. The proposal generally complies with Section B3.11 of the Pittwater DCP and Clause 5.21 of the Pittwater LEP. The proposal is therefore supported.’’

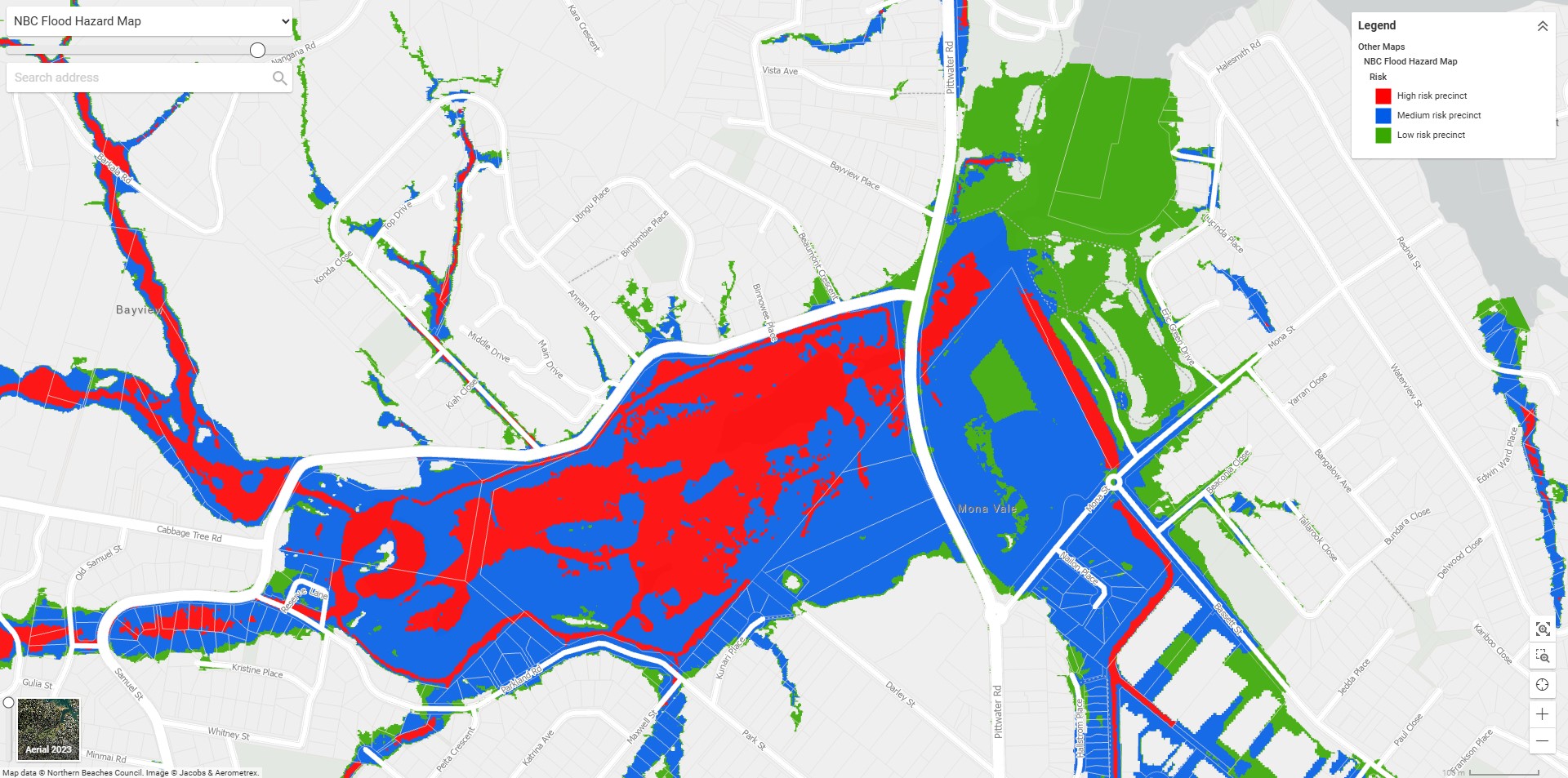

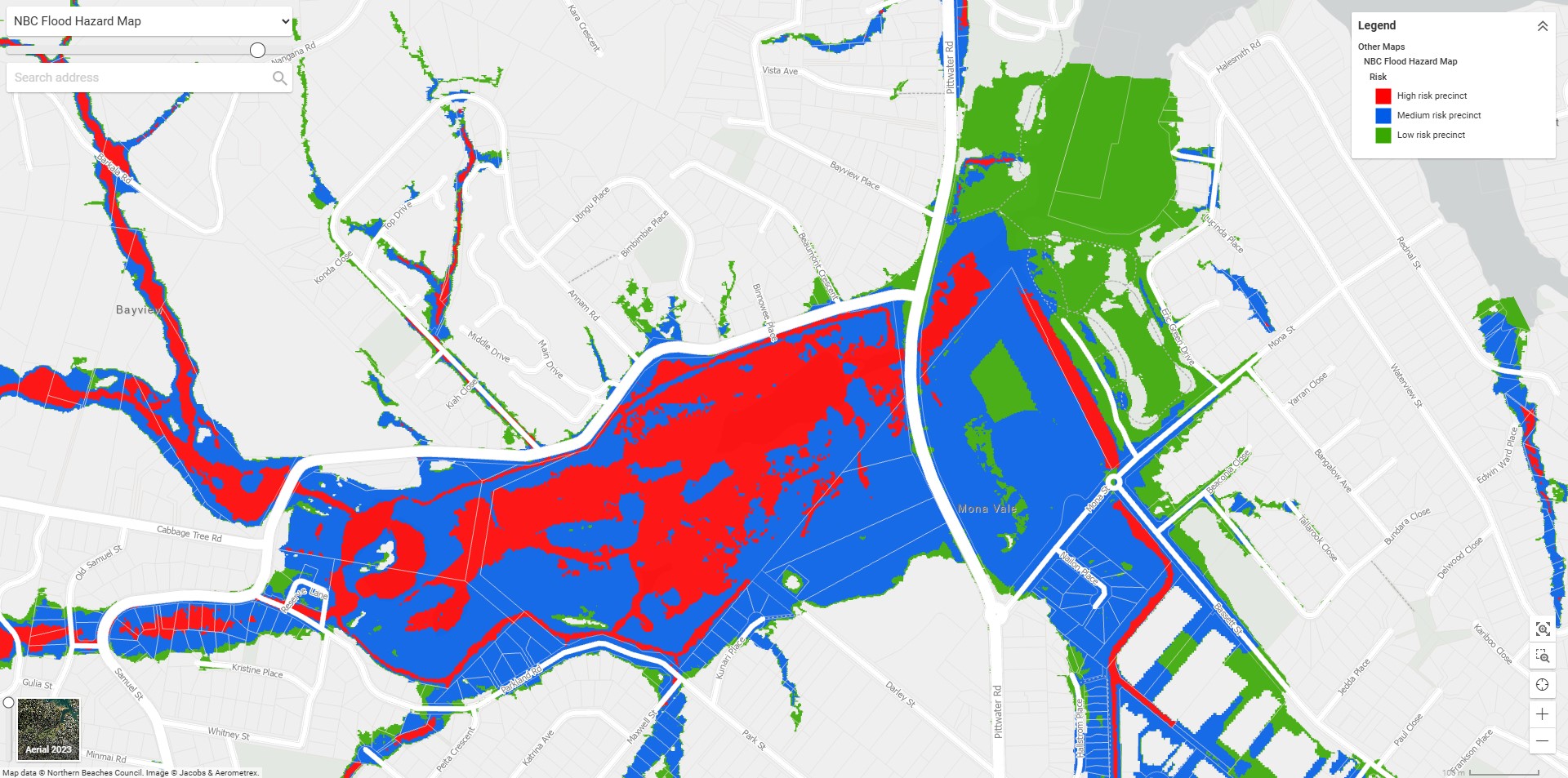

A 2023 NBC Flood Hazard Map does show that that corner, of Park streets and Kunari Place, is not within a known flood zone - on one side of that street:

screenshot of 2023 NBC Mona Vale Floodplain map and - Sections from -:

.jpeg?timestamp=1771390604386)

The NB council states on its Local Environmental Plan and Development Control Plan webpage that:

'On 14 October 2025 the NSW Government advised that the Planning Proposal for the draft Northern Beaches LEP may proceed subject to a range of matters including certain amendments and details for Council to apply prior to the public exhibition of the Planning Proposal in 2026. The new, consolidated LEP for the Northern Beaches will be complemented by a new comprehensive Development Control Plan (DCP), which is being developed in parallel to the LEP.'

As such the Pittwater Council LEP and DCP are still the determining documents and requirements applicable. These were informed by reports and studies commissioned by Pittwater Council which include, but were not limited to, the Mona Vale / Bayview Floodplain Risk Management Study and Plan 2008 Volume 1 and Volume 2- produced by Cardno Lawson Treloar for Pittwater Council.

The Pittwater Council DCP provides that, in regards to:

FLOOD EFFECTS CAUSED BY DEVELOPMENT

Development shall not be approved unless it can be demonstrated in a Flood Management Report that it has been designed and can be constructed so that in all events up to the 1% AEP event:

(a) There are no adverse impacts on flood levels or velocities caused by alterations to the flood conveyance; and

(b) There are no adverse impacts on surrounding properties; and

(c) It is sited to minimise exposure to flood hazard.

Major developments and developments likely to have a significant impact on the PMF flood regime will need to demonstrate that there are no adverse impacts in the Probable Maximum Flood.

CAR PARKING requirements are:

D1 Open carpark areas and carports shall not be located within a floodway.

D2 The lowest floor level of open carparks and carports shall be constructed no lower than the natural ground levels, unless it can be shown that the carpark or carport is free draining with a grade greater than 1% and that flood depths are not increased.

D7 All enclosed car parks must be protected from inundation up to the Probable Maximum Flood level or Flood Planning Level whichever is higher. For example, basement carpark driveways must be provided with a crest at or above the relevant Probable Maximum Flood level or Flood Planning Level whichever is higher. All access, ventilation and any other potential water entry points to any enclosed car parking shall be at or above the relevant Probable Maximum Flood level or Flood Planning Level whichever is higher.

However, the NB council has been working to update the Mona Vale Floodzones and Floodplain documents. The council webpage for that states:

‘’Following the completion of the McCarrs Creek, Mona Vale and Bayview Flood Study project in 2017, Council recently commissioned engineering consultants BMT to complete a comprehensive Floodplain Risk Management Study for the McCarrs Creek, Mona Vale and Bayview catchments.

This study will consider a range of flood management measures, such as structural options (levees, detention basins etc.), emergency management improvements, community awareness activities and land use planning. The options will be assessed to understand the potential impacts and benefits, with a final suite of recommended options presented in the McCarrs Creek, Mona Vale and Bayview Floodplain Risk Management Plan. This project is supported by the NSW Government’s Floodplain Management Program.’’

The 'Project Lifecycle' and 'Updates' provides

April 2019 - Project update: We would like to get your thoughts and suggestions on flood management options to reduce flood risk and improve emergency response planning for the catchments of McCarrs Creek, Mona Vale & Bayview. This short survey is your opportunity to contribute local knowledge to help with our future planning for the area. Please complete the survey online.

Timeline item 1 – complete; Data Collection, Review and Community Consultation - June 2019. Comments close 16 June 2019. Further opportunities to comment on flood management options during the public exhibition of the draft Study and Plan later in the year.

Updates: May 2020 - Study being prepared

Timeline item 2 - incomplete; Public Exhibition of Draft Flood Risk Management Study; Expected in 2024

Following the council announcing residents of Belrose, Davidson, Frenchs Forest, Forestville, and Killarney Heights can share their views on its draft Middle Harbour Flood Study in the first week of February 2026, on Tuesday February 10 2026 the news service inquired of the council when the 'Public Exhibition of Draft Flood Risk Management Study' for Mona Vale would be available.

Council responded on Friday February 20, stating:

''Council continues to progress important flood management work across the Northern Beaches. Several Flood Studies and Flood Risk Management Plans are under way and/or programmed with the McCarrs Creek, Mona Vale and Bayview Floodplain Risk Management Study and Plan scheduled for public exhibition and adoption in the 2027/28 financial year.

Council has already completed the following work for McCarrs Creek, Mona Vale and Bayview:

- Stage 1: Flood information assessments and community consultation

- Stage 2: Risk assessment and emergency management arrangements

- Stage 3: Assessment of preferred flood risk management options

The remaining steps involve finalising the Draft Floodplain Risk Management Study, undertaking public exhibition and then presenting the Study and Plan to Council for adoption.'

No indication of what was in that feedback provided in 2019 is available yet, or whether that would have changed any of the DA's since 'supported' by the council if its original timeline for updating the Mona Vale-Bayview-McCarrs Flood Risk Management been realised.

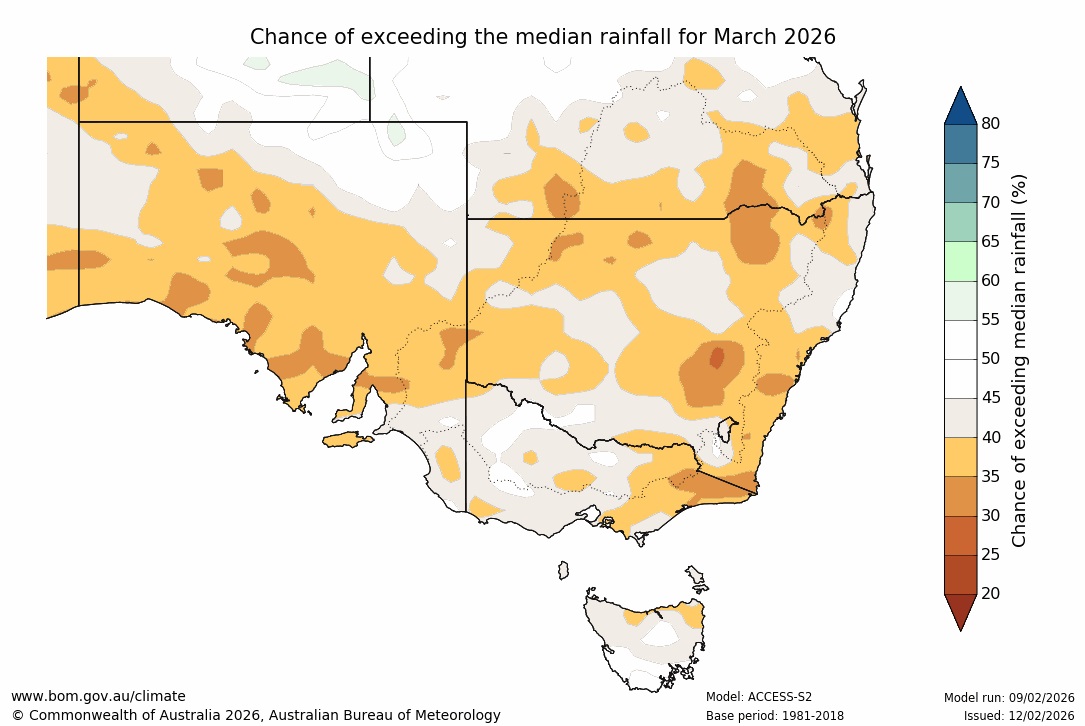

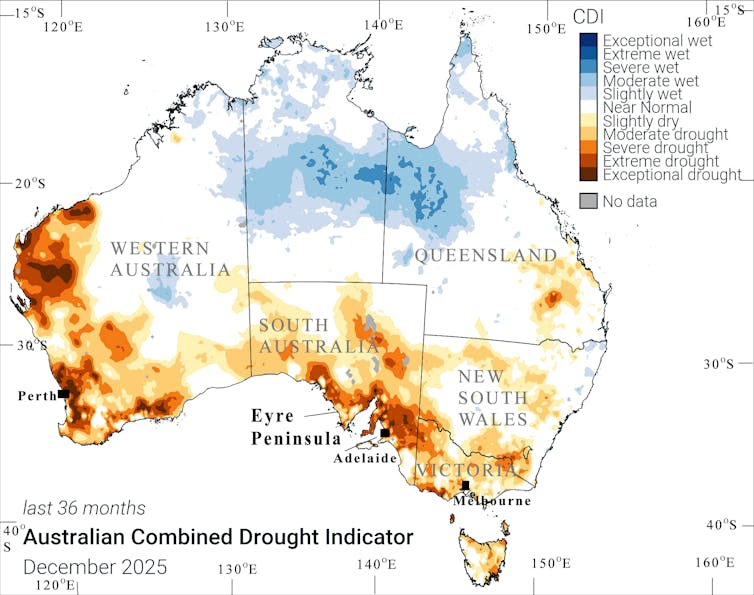

However, residents of Mona Vale state they are well versed in where water flows across this former floodplain and wetland, and have kept records of their own, some of these stretching back generations. They have said the cumulative impacts of climate-change driven weather events are already here and occurring on a larger scale more frequently.

The recently released NSW State Disaster Mitigation Plan estimates that by 2060 Sydney's northern beaches will have the highest Total Average Annual Losses in NSW by 2060, with estimated losses of close to $1 billion dollars per annum to the built environment alone.

During the ‘Ability of local governments to fund infrastructure and services’ NSW Parliament Inquiry a question to the Chief Financial Officer, Northern Beaches Council revealed a deficit of almost $8million in costs sustained by weather events.

The CFO's Answers to Questions on Notice the response to 'What types of costs are incurred in response to a natural disaster?' was:

The Northern Beaches is highly exposed to a raft of natural hazards with current data indicating:

- Over 22,000 properties are affected by flood;

- 19,000 properties are bush fire prone;

- 63,000 properties exposed to moderate to high geotechnical risk, and

- close to 5000 properties affected by coastal hazards.

See:

Some residents have communicated that when the council chooses to participate in a Section 34 conciliation conference, this practice effectively denies due process to the community in relation to the observance of the Pittwater LEP and the interests of the community in the proper consideration of D/A’s. They have observed that the NB council will spend Pittwater ratepayers money to defend the same in the former Warringah council area.

See:

The council is not the sole driver of support for DA's residents state will 'obviously cause more flooding and distress and leave us with a huge and ongoing bill'. No matter how quickly councils may be able to update their mitigation structures to reflect what is happening on the ground, other policies at a state government level are increasingly overriding democracy within local government, and even placing delays on council actions - from informed studies and data-driven knowledge.

In October 2017 the then Coalition NSW government the draft Greater Sydney Region Plan was released which named Mona Vale as a 'Town Centre'.

This had been preceded in 2016 by the then installed by the Coalition Government Administrator, when Pittwater was forcibly amalgamated with Warringah and Manly, publishing another 'new' version of the prior Pittwater Council's 'Mona Vale Place Plan' which it had been working on when destroyed.

Although abandoned by that Administrator, as it was clearly being taken up by the NSW Government the following year, this stated it would, now, reflect what has been passed by successive Liberal and Labor governments.

At an October 2016 Meeting community leaders stated:

''Our community involvement has now been muddied by a place planning process that we were largely not included in. We have before us a plan that has a complete disconnect to the workshops held, a draft Plan that challenge’s what our ideas for Mona Vale were. Did we really, say, that we wanted six story buildings? Did we really, say, that we wanted a night time economy like Manly? No, we did not. In fact, one of the big points of difference that we identified to our neighbours in the south, was our low-rise landscape and the human scale and village character of our town centre. We identified as being an area of important low key tourism along with our village neighbours to the north and could see this as an attraction to tourists, investors and talent that could help build our economy. Six storey high buildings are not part of the character that we envisage for Mona Vale and will destroy our village feel. We do not wish to see developers coming in and developing whole precincts, setting a precedent for development in surrounding localities.''

''We already have the real estate agents spruiking the increases to property prices with a revamped Mona Vale and there is still no evidence that Mona Vale needs greater housing stock. Affordable housing does not equate to six storey high buildings.

We still do not know what the economic/environmental cost of population growth equates to in our area. What we do know however is that there is no reference to increased infrastructure in the plan. Only an improved bus service. There is no reference to an upgrade of the sewerage works or water systems and drainage. No reference to our crowded schools. With the continued development of Warriewood and the large land release in Ingleside, the introduction of town house legislation, and the interest in secondary dwellings on the peninsula, it does not paint a pretty picture. We need to respect the carrying capacity of our area when planning for our future.''

This place plan does not represent the communities’ desires. The process has been politically managed and PR dominated. Six thousand hits on a website does not constitute meaningful consultation. The State Government, The Property Council of NSW, The Future Cities group, local real-estate agents, mortgage brokers and banks, the developers waiting in the wings, should not be responsible for the evolution of Mona Vale. Nor should an unelected council executive who are pushing for densification and changes to our LEP.''

See:

The incumbent Labor NSW Government is in the process of changing that 2017/2018 GSRP to 'The Sydney Plan'. The draft Sydney Plan sets out how the NSW Government will manage growth across the Sydney region over the next 20 years. Once finalised, it will replace the Greater Sydney Region Plan – A Metropolis of Three Cities (2018) and associated district plans as the first of a new generation of regional plans outlined in A New Approach to Strategic planning: Discussion Paper. The draft Sydney Plan is currently on exhibition and open for feedback until 5 pm, 27 February 2026.

Mona Vale was maintained as a 'Town Centre' and approved for 6-storey buildings up to 24 metres under the State Government's Low and Mid-Rise policy announced on Friday February 21 2025.

Sites were selected considering the following criteria:

- Access to goods and services in the area

- Public transport frequencies and travel times

- Critical infrastructure capacity hazards and constraints

- Local housing targets and rebalancing growth

The buses in the B-line, newly finished upgraded Mona Vale Road East, already ticked off 'Mona Vale Town Centre' prior to feedback, and the council continuing this through its own housing policy, as required at a state level, outweighed what this will do to this part of Pittwater and all those who buy into it.

However, with councils bypassed through NSW Government State Significant Development (SSD's), developers are now taking that minimum Height of Buildings as the baseline, zones for areas as irrelevant, and applying to fill whole blocks with proposals almost three times over the limit, in, once again, known flood zones or on sand.

See:

Residents have stated they are outraged any state government or council expects them to pick up the tab for their past, current and future policies to enable developers greed to be prioritised at the expense of community safety, and approval of environment destruction.

Another factor has become more apparent in the past few weeks.

The cost of construction has increased so much that developers are abandoning projects in the western suburbs of Sydney in favour of builds in Pittwater and surrounds where the profit margins make these more attractive.

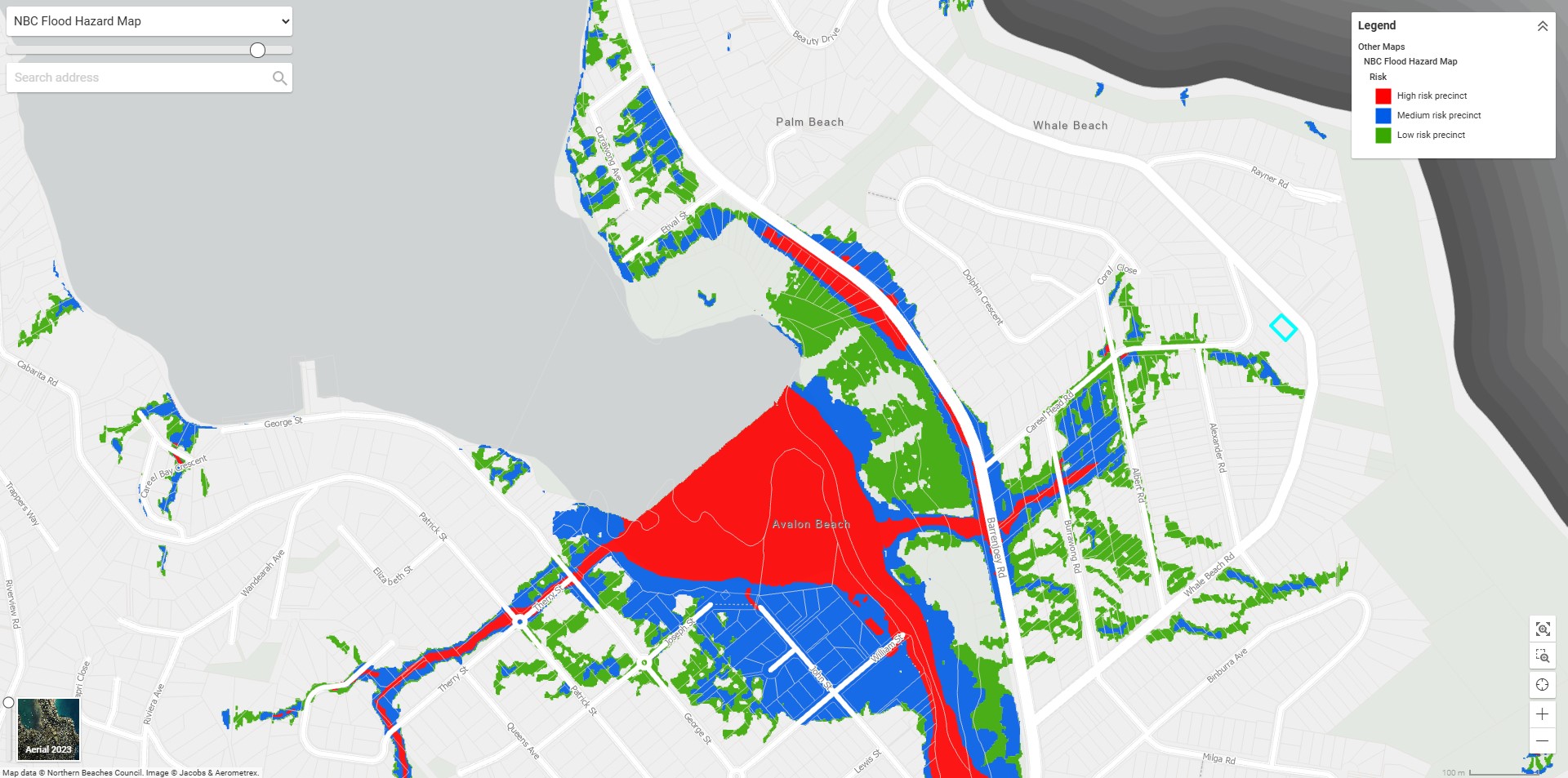

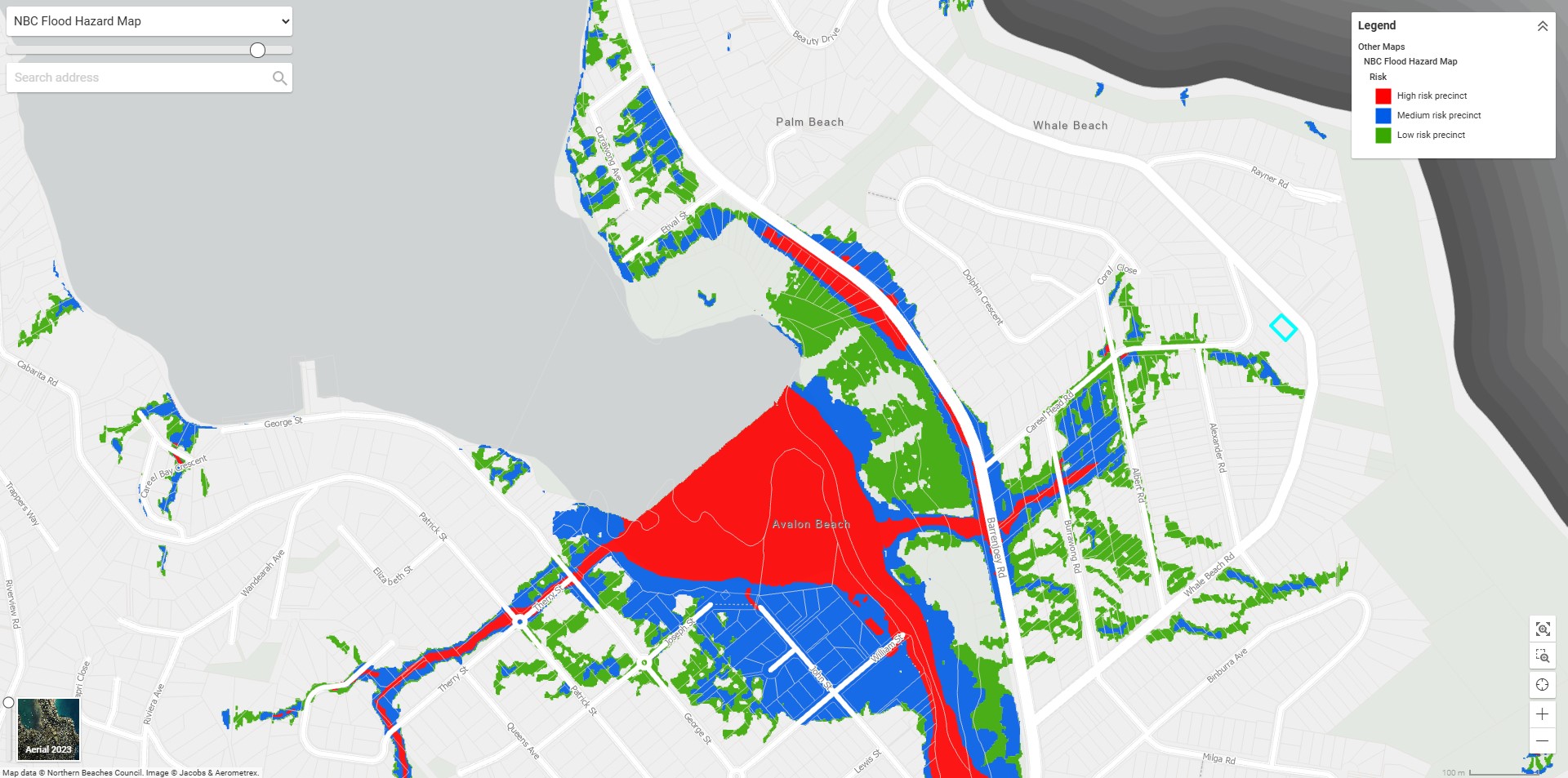

The approval of another underground carpark on the corner of Careel Head and Barrenjoey road in a DA, in another known high risk flood area, where people are seen weekly blowing refuse, into the gutters and blocking drains, and still unchallenged despite reports to the council, is already increasing the level of flooding and inundation of properties alongside this flood zone.

Critics argue that building on or adjacent to floodplains or known flood zones puts lives at risk and, obviously, increases insurance costs - which is, as seen above, is set to be imposed on all residents, not the developers profiting from the same, and as the councils cannot be sued for 'supporting' the same, the huge loss of environment, costs levied on all residents, and ongoing mitigation costs to those who buy into such developments is being sacrificed so developers may profit.

The view north from Careel Head Road, North Avalon in 2022: This frequently flooded corner was causing drivers to cross over the lines into the other lanes to avoid the flooded section.

Careel Head-Barrenjoey Road section, January 17 2026 - more flooding, more often. Photo: Adam L'G/FB

screenshot of 2023 NBC Careel Head Road and Careel Bay Floodplain risk map - does this need updating again, already?

Housing Targets Rejigged

On May 29-31, 2024, the NSW Government released 5-year housing completion targets for 43 local councils across Greater Sydney, Illawarra-Shoalhaven, Central Coast, and Lower Hunter. These targets aim to deliver 377,000 new homes by 2029 to align with the National Housing Accord, focusing on infill development near existing infrastructure. The State Government is going to these lengths to ensure everyone has a roof over their heads.

Analysts agree Australia's housing crisis stems from a significant imbalance where demand far outstrips supply, driven by rapid population growth (including migration and international students), insufficient new construction (hampered by complex planning and high costs), decades of underinvestment in social housing, and housing being treated as an investment commodity rather than a basic need or human right, leading to soaring prices and rents.

The Northern Beaches Council had already set a target of almost 12,000 new dwellings by 2036 in 2021 under the previous government's requirements. It adopted this at the meeting held on 27 April 2021. Areas for high-density development include Dee Why, Mona Vale, Frenchs Forest, and Brookvale.

The NB council proposed, at that time, a locally specific medium density complying development model as an alternative to the Low-Rise Medium Density Housing Code. Additionally Council proposed seniors and affordable housing as an alternative to the new Housing SEPP (formerly the Affordable Rental Housing 2009 and Seniors and People with a Disability 2004 SEPPs) which were not supported by the then Coalition Government.

The department’s requirements meant the council cannot pursue everything in its strategy. This included exemption from the Housing SEPP which provides for different housing types such as seniors living and boarding houses.

The 2024 target made the NBC LGA quota 5,900 new completed homes by 2029. In comparison, Mosman Council must supply 500 new complete homes, although that may soon change.

See: Sale of Bulk of HMAS Penguin Site Approved - Pristine Angophora Forest Likely to be Destroyed, Wildlife Killed, Another People's Parkland stolen: Pittwater Annexe will be retained

Councils that meet or exceed these targets can access a $200 million grant pool for community infrastructure like parks and sports facilities.

Concerns are that these targets, focused on completions rather than approvals, may be difficult for councils to control, and that rapid development could affect building quality or the pressure on councils to meet their assigned targets by supporting proposals that will impact homes and residents already in these places - as exampled in the Mona Vale DA's being lodged and passed, as well as the SSD's now seeing proposals to increase what had already been approved, in one instance, in these flood zones.

See: Doubling of prior Bassett Street Mona Vale DA proposal under NSW government SSD's provides stark illustration of impact on local environment of laws written 'for developers' - Community Objections Being silenced or Ignored

New guide to support councils in identifying land for affordable housing

In addition to the CCNH SEPP, this week, on Wednesday February 18, the NSW Government announced its release of a new guide to support councils in undertaking their own land audits to identify vacant operational council land that could be used to deliver affordable housing projects.

The Council Led Affordable Housing on Operational Land Guide released by the Office of Local Government provides step-by-step guidance for councils on identifying and managing affordable housing sites utilising operational land – from planning through to construction and delivery.

'A major barrier to building more affordable housing is the high cost of acquiring well-located land. Council owned sites such as former depots or unused facilities that are well serviced and close to public transport can be ideal locations for affordable housing to support low-income households.' the statement reads

'The guide provides detail on delivery options available to councils to release and manage operational land for affordable housing and how councils can form partnerships with entities such as government agencies and housing providers to maximise the impact of affordable housing.'

It also includes case studies showcasing successful affordable housing projects led by councils to meet the needs of their communities. For example, Shoalhaven City Council transformed surplus council land in Bomaderry into 39 affordable housing units, while Lismore City Council is partnering with Landcom, Homes NSW and a community housing provider to construct 56 new affordable housing units.

'The NSW Government has set five-year housing completion targets for 43 local government areas in Sydney, the Illawarra-Shoalhaven, the Lower Hunter and Central Coast, and a single housing target for Regional NSW. In the draft Sydney Plan, out on exhibition at the moment, local affordable housing contribution schemes have been mandated for all councils in Sydney to increase the delivery of affordable homes within their communities.'

'This guide also supports the objectives of the National Housing Accord by encouraging councils to increase housing supply and affordability at the local level.

By harnessing under-utilised operational land in partnership with the NSW Government and community housing providers, councils can make a substantial impact in addressing the state’s housing crisis and deliver access to homes for people in need.'

The guide is available at: https://www.olg.nsw.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/Guide-for-Council-Led-Affordable-Housing-on-Operational-Land.pdf

Minister for Planning and Public Spaces Paul Scully said:

“All levels of government need to play their part to help address the housing shortage. The Minns Labor Government’s land audit has identified several sites that are no longer being used that can deliver thousands of new homes, with the support of this new guide, we’re asking councils to do the same.

“This builds on the work of our successful Infill Affordable Housing Scheme, the delivery of 400 build-to-rent homes for essential workers on land audit sites in Annandale and Chatswood and mandated minimum affordable housing inclusions for new developments in Transport Oriented Development areas.”

Minister for Local Government Ron Hoenig said:

“Former council depot sites and other surplus buildings often sit on valuable land that could be better utilised for much-needed housing.

“This new guide provides councils as key partners in delivering housing, with the information and tools to address housing affordability in their area.

“Affordable housing is critical for fostering community diversity, boosting local economies and promoting long-term sustainable housing, and councils can help free up unused land to create homes for our key workers and future generations.”

Minister for Housing and Homelessness Rose Jackson said:

“This is what solving the housing crisis looks like – it means looking at it from every angle, pulling down barriers at every turn.

“We’re working constructively with many councils who want to build more affordable housing for their communities, but sometimes it can be hard to know where to start.

“That’s where this guide comes in. We’re providing the tools to help councils get more projects off the ground, doing their bit to build a future for young Australians."

Have your say: Climate Change and Natural Hazards SEPP

The NSW Government is seeking feedback on its proposed Climate Change and Natural Hazards State Environmental Planning Policy (SEPP).

''The proposed policy introduces a clear, consistent framework for tackling current and future risks, including climate change and natural hazards (coastal hazards, flooding, bushfires, and urban heat), and rebuilding after natural disasters''. the webpage states

'By bringing climate change and natural hazard frameworks together in one place, the policy makes planning controls easier to access, understand, and apply.

The policy will support the new object in the Environmental Planning & Assessment Act 1979 to better respond to these risks and make decisions that reflect the level of risk involved'.

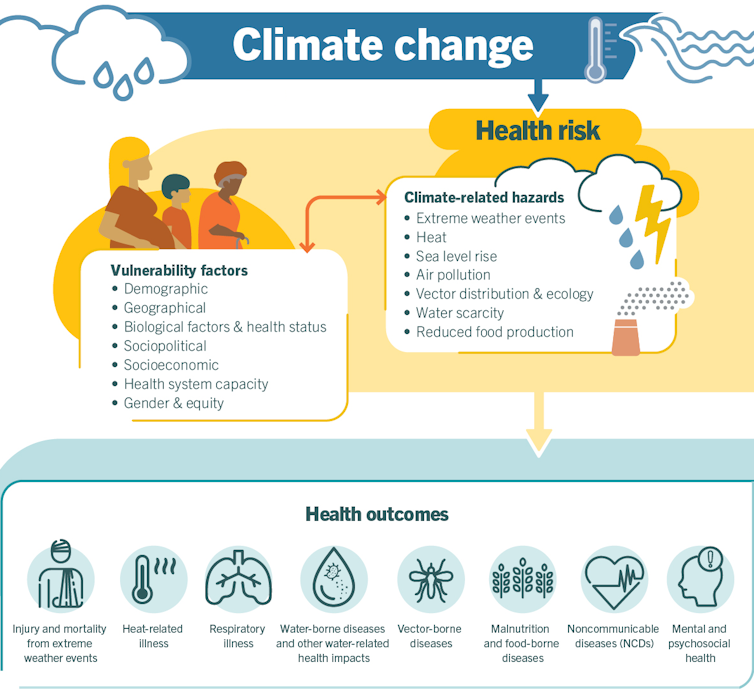

The government states the proposed policy will:

- Introduce new guidelines for managing natural hazards and update existing natural hazards controls to streamline decision-making.

- Focus on climate risks, rebuilding after natural disasters, coastal hazards, flooding, bushfires and urban heat.

- Establish a consistent approach for assessing climate risk and natural hazards throughout development assessment.

- Provide an all-hazards approach to planning to ensure communities and developments are resilient to both current and future risks.

- Help consent authorities, such as local councils, assess climate and natural hazard risks for different development types and guide decisions based on acceptable risk levels.

As part of the exhibition, the government is also seeking feedback on:

- Draft Climate Change Scenario Guidelines outlining climate scenarios to be used with natural hazard frameworks.

- Draft Urban Heat Policy Statement detailing objectives and planning principles to build resilience to urban heat.

The proposed SEPP will replace the existing State Environmental Planning Policy (Resilience and Hazards) 2021.

''Your feedback is valuable and will help inform the making of the Climate Change and Natural Hazards SEPP. A submissions report will be available on this page once the review is complete.'' the webpage states

Read the Explanation of Intended Effect

Related documents

The proposed policy is on exhibition through an Explanation of Intended Effect until 5pm on Monday, 16 March 2026.

Documents and Feedback page at: www.planningportal.nsw.gov.au/draftplans/exhibition/have-your-say-climate-change-and-natural-hazards-sepp

A 'tolerable level of risk'

The 'intended effect' document states:

'Supporting planning and consent authorities to consider future climate risk should not slow the development process or add unreasonable cost. The proposed CC&NH SEPP will consider climate and natural hazard risks early in planning decisions to reduce risk, deliver economic benefits, including minimising future costs associated with insurance and recovery after a disaster, and ensure homes are delivered in the right locations. There are existing natural hazard frameworks that require consideration of individual hazards, such as for flood, coastal hazards and bush fire.

However, anecdotally, there is often uncertainty about how these frameworks relate, how they should inform the decision-making process and whether they are targeting risk at an appropriate point in the planning cycle. Additionally, other natural hazards and climate change impacts, such as heatwaves and urban heat, have less mature planning system responses and frameworks in place.

Given human nature, there is also often a perception that the most recent hazard faced should be the most important consideration.

This EIE outlines proposals to remove provisions in existing environmental planning instruments and replace them with consolidated provisions in the CC&NH SEPP. It also proposes a new Ministerial Direction to complement the CC&NH SEPP at the rezoning stage, a new NSW Urban Heat Policy for Land Use Planning (Urban Heat Policy) and seeks feedback on potential urban heat provisions that would extend the emerging natural hazard framework for heatwaves and urban heat.

The CC&NH SEPP will seek to help planning and consent authorities consider a development proposal based on that proposal’s scale and context, recognising that different developments will have different risk profiles over time, with the aim of delivering a final decision that represents a tolerable level of risk. To achieve this, the CC&NH SEPP will include the following overarching principles:

- planning decisions consider future climate risk and relevant natural hazards

- planning decisions reduce future exposure and vulnerability to natural hazards and climate risk

- planning decisions appropriately balance and manage future costs and risk to life from natural hazards and climate risk

- planning decisions improve the health of Country (therefore Aboriginal communities) in a changing climate.

The CC&NH SEPP will apply state-wide through existing natural hazard frameworks. Provisions for individual hazards will continue to apply to areas as mapped or identified as applicable to specific hazard clauses. It will also apply to local development, State significant development and State significant infrastructure.'

Page 13 of the 'Intended Effect' document states:

‘’SI LEP clause 5.22 – special flood considerations It is proposed to move clause 5.22 (optional) into the CC&NH SEPP. Currently, clause 5.22 applies in 42 LEPs across NSW. As part of submissions to this EIE, councils are encouraged to identify if they would like to opt in to clause 5.22 in the CC&NH SEPP. The CC&NH SEPP will not make clause 5.22 mandatory, and this EIE seeks feedback on the local government areas to which the new clause will apply under the CC&NH SEPP. It is proposed to update the clause to standardise the sensitive and hazardous land uses to which it applies, and to consider updates relating to risk-based decision making, co-incident flood and coastal hazard impacts, consideration of shelter-in-place and other evacuation related issues.’’

Flood prone land mapping

Flood prone land maps are published and maintained by councils or where relevant, State Government. These maps identify where planning processes must consider flooding. It is proposed to include a clause in the CC&NH SEPP giving effect to flood prone land maps prepared by each council or planning authority. The CC&NH SEPP will not include these maps, but these should be available on the relevant council website and/or on the NSW State Emergency Service flood data portal.’’

Worth noting is Planning circular, Issued 1 March 2024 'Update on addressing flood risk in planning decisions' ;

This states:

'As outlined in the Considering flooding in land use planning guideline, councils should also update their development control plans (DCPs) to indicate the relevant flood planning levels and flood planning areas that have been identified through the FRM process and where they apply.'

Development assessment

Before determining a development application (DA), the consent authority is required to undertake an evaluation of the proposed development in accordance with relevant legislation, plans, development controls, policies and guidelines. Provisions that may be applicable to flood-related planning assessment include:

- section 4.15 Evaluation (EP&A Act) – Identifies matters to consider when determining DAs, including associated LEP and DCP requirements that may include flood-related development controls

- clause 5.21 Flood Planning (Standard Instrument – Principal Local Environmental Plan (SILEP)) – Compulsory LEP provision with considerations and requirements for development proposed within the flood planning area

- clause 5.22 Special Flood Considerations (SILEP) – Optional LEP 2 provision with requirements for sensitive and hazardous development on land between the flood planning area and the PMF, and other development on land that may present a flood safety risk.

Acronyms: Probable Maximum Flood (PMF) and Flood Risk Management (FRM).

Proposed Climate Change and Natural Hazards SEPP welcomed by insurers

Insurer Suncorp welcomed the New South Wales Government’s proposed reforms of its planning framework, which it states would strengthen the assessment of climate and extreme weather risks when approving new homes.

The announcement comes after Suncorp released its public policy paper, Affordable and Resilient Private Housing Supply, at the insurer’s Future Housing Roundtable in Canberra in October 2025.

Suncorp’s roundtable brought together leaders from insurance, housing, and government to develop practical solutions to build affordable homes better equipped to withstand extreme weather events.

Suncorp CEO Steve Johnston said the proposed Climate Change and Natural Hazards State Environmental Planning Policy (SEPP) represents a significant step forward in building resilience to extreme weather across NSW and sets a new national benchmark for climate-responsive planning.

Suncorp CEO Steve Johnston said:

“We have seen the results of fragmented legislative and regulatory frameworks lead to a concerning number of new homes being approved in floodplains, bushfire-prone areas and coastal regions exposed to inundation,"

“We commend the Minns Government for taking action to deliver more sustainable and climate-resilient housing across the state.”

Mr Johnston said past decisions to allow unsuitable construction in floodplains and bushfire-prone greenfield sites were directly contributing to cost-of-living pressures for homeowners.

“Insurers are dealing with the fallout. In the past five years alone, insured losses in Australia from extreme weather have reached an estimated $22.5 billion — up 67 per cent from the previous five-year period — and the risks continue to rise,” Mr Johnston said.

"When thousands of homes are built in high-risk areas, higher insurance premiums and greater financial exposure for households and the government are the inevitable result. This is why it is essential to factor climate and natural hazard risk into new housing approvals.” Mr Johnston said.

Meanwhile, residents of Pittwater state they are still waiting on due process, and getting out the gum boots when more rain is forecast to be heading their way.

![]()

.jpeg?timestamp=1771390604386)

The powerful owl (Ninox strenua), a species of owl native to south-eastern and eastern Australia, is the largest owl on the continent. It is found in coastal areas and in the Great Dividing Range, rarely more than 200 km (120 mi) inland.

The powerful owl (Ninox strenua), a species of owl native to south-eastern and eastern Australia, is the largest owl on the continent. It is found in coastal areas and in the Great Dividing Range, rarely more than 200 km (120 mi) inland.

%20(1).jpg?timestamp=1675893929686)

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

.jpg?timestamp=1770949312135)

%20smaller.jpg?timestamp=1770949793984)

%20smaller.jpg?timestamp=1770950747924)

%20smaller.jpg?timestamp=1770950809955)

.jpg?timestamp=1770950842729)

.jpg?timestamp=1770950870338)

.jpg?timestamp=1765592323370)

%20smaller.jpg?timestamp=1769645602951)

%20smaller.jpg?timestamp=1769645638078)

%20smaller.jpg?timestamp=1769645668722)

%20mumma%20smaller.jpg?timestamp=1769645238812)

%20smaller.jpg?timestamp=1769644965301)

.jpg?timestamp=1769645711165)

%20smaller.jpg?timestamp=1769645775148)

.jpg?timestamp=1769645809209)

.jpg?timestamp=1769645866040)

Shorebird Identification Booklet

Shorebird Identification Booklet