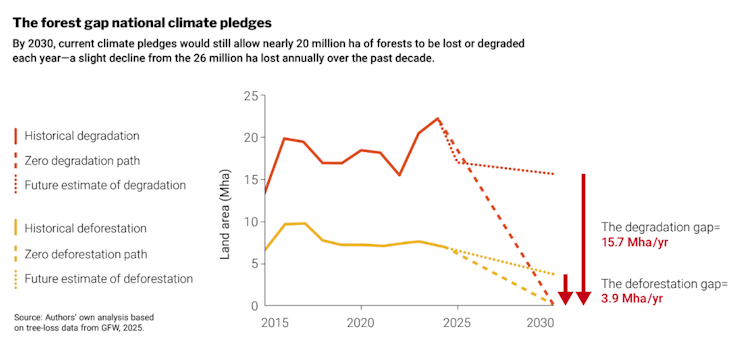

Destruction of 670 trees and baby birds during nesting season for transmission infrastructure proves biodiversity offsets are nature negative - you cannot 'offset' a tree that's 200+ years old

December 2, 2025

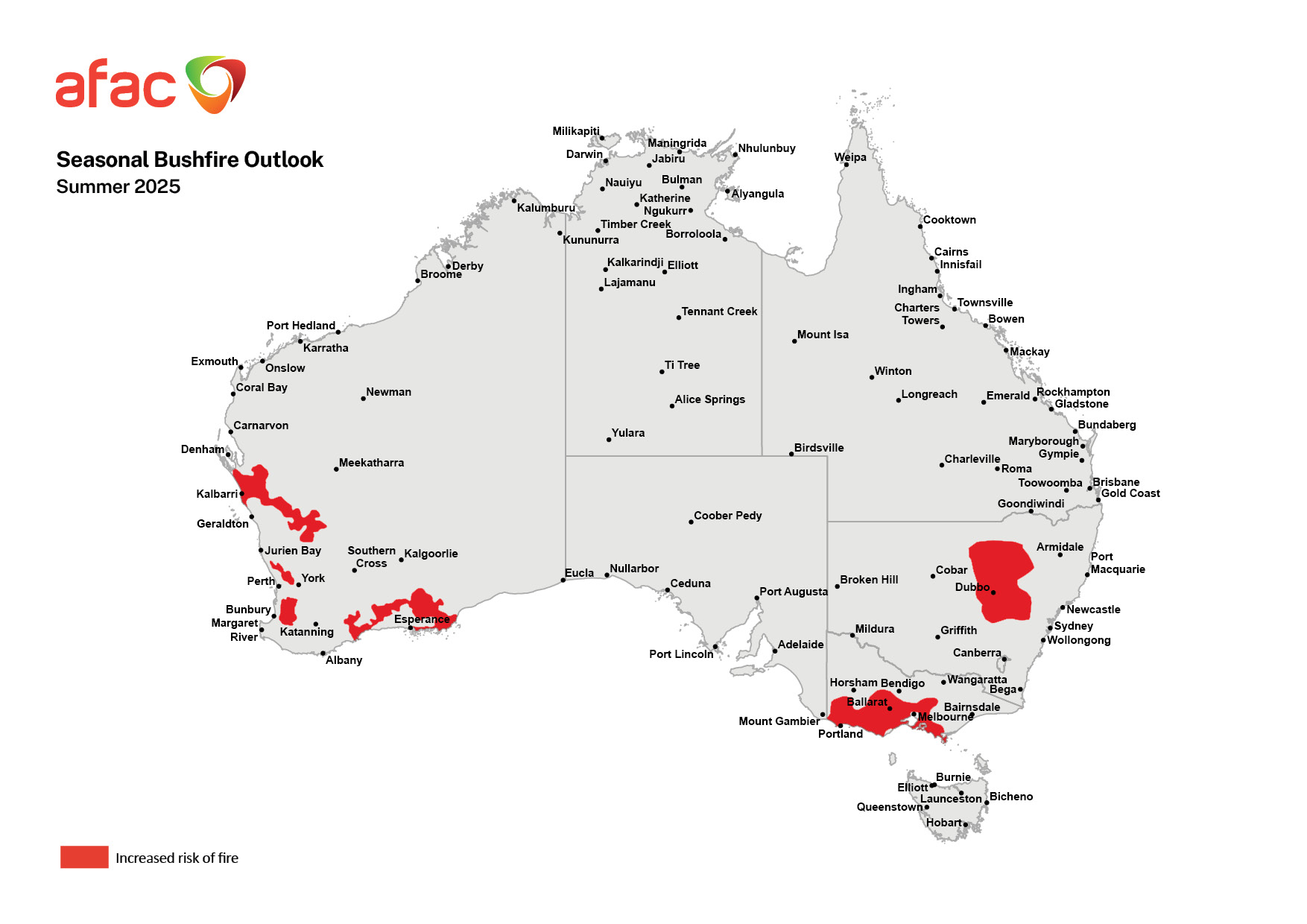

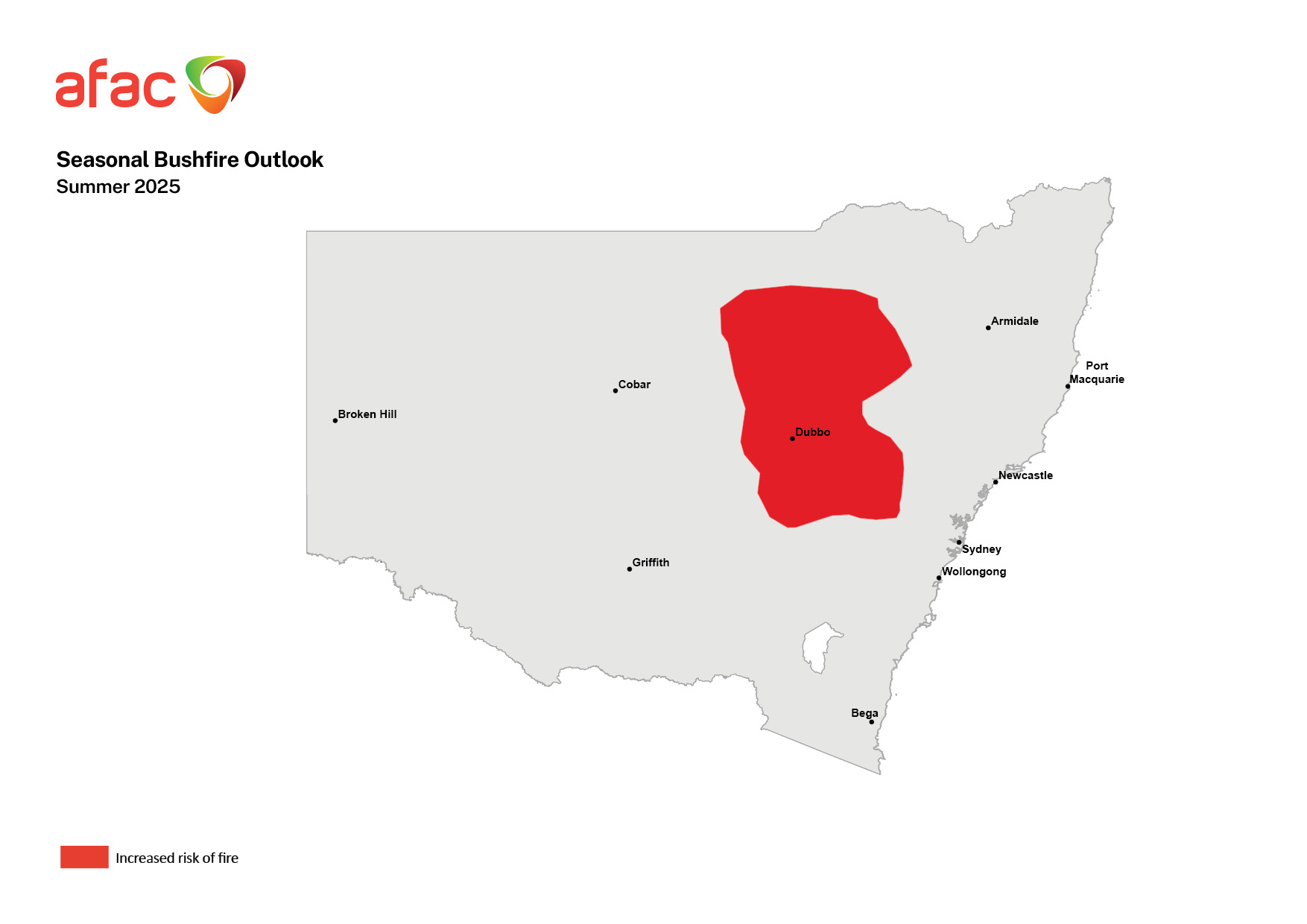

Labor Premier Chris Minns and Environment Minister Penny Sharpe, who has been in Japan for the week, are facing criticism from multiple sides of local government, wildlife carers, a cycle group and politics over their handling of the Central West Orana Renewable Energy Zone (REZ) following revelations that native vegetation has been cleared to make way for a renewable energy project during nesting season.

An estimated 670 trees have been cleared, including critically endangered hollow bearing trees hundreds of years old, which make up habitat for koalas, glossy black cockatoos, little eagles, squirrel gliders and eastern pygmy possums. This destruction of native vegetation has resulted in the displacement of at least 60 chicks and dozens of threatened baby birds.

Mudgee Vet Hospital said about 60 hatchlings, including kookaburras, kestrels, rosellas and galahs had been brought in by workers since late October.

"We were inundated without any warning and just horrified at the numbers," veterinarian Paige Loneregan said.

"It's very distressing for all our staff, we've never had this many baby birds ever."

Some chicks had to be euthanised because of broken bones.

Mid-Western Regional Council said it was told five weeks ago that renewable energy company ACEREZ would be removing 670 established trees from a roadside north of Mudgee. The clearing sparked community outrage after images of the displaced baby birds emerged.

The council's general manager Brad Cam said the community and council had been lobbying for more than 12 months to prevent the land clearing.

"[It's] exactly what I thought was going to happen, so very disappointed, very frustrated that we weren't listened to, or it was certainly dismissed as not a critical event," he said to the ABC

"It could have been avoided and it hasn't because it's just poor planning."

Central West Cycle Trail, which maps out quiet country roads, had raised concerns about plans to remove the vegetation and wrote to the state government months ago suggesting the road be built on adjacent EnergyCo-owned land which would not require clearing.

The NSW government's EnergyCo referred all media queries to ACEREZ and provided a media release about a $140 million biodiversity offset program.

The release, from October 2025 when the tree-killing commenced, reads "the Minns Labor Government is showing that renewable energy and nature conservation can go hand-in hand" and states how it will invest in biodiversity offsets in the region and include creating wildlife corridors and habitat connectivity.

In a statement, an ACEREZ spokesperson said it is "liaising with WIRES and working with Taronga Wildlife Hospital at Dubbo … to care for any birds displaced by the clearing required".

"Ecologists and fauna spotters are also onsite to ensure the birds can be safely relocated or taken to vets or wildlife carers," the spokesperson said.

However, critics have pointed out that you cannot have so many baby birds coming into care if fauna spotters and ecologists have already checked the trees, and you cannot replace trees that are hundreds of years old and producing the hollows so many species need as a home. Even if they could be transplanted to the destroyed area, there aren't enough trees that are hundreds of years old left to enable this.

Central West Cycle Trail's Barbara H, whose photos run below, stated on November 29:

''It has been a very sad time receiving many baby birds from the removal of the trees, shown below !! I am a volunteer carer at Mudgee and one of the team the manages the CWC . So when I received young birds in and ‘Merotherie” and “tree felling“ was written on the information sheets with the birds, I knew exactly where they had come from. ''

''[this is] A terrible injustice for the wildlife out there !! And many died after being taken in care as they had many injuries their little bodies didn’t show.''

Rosellas

Kestrels

More rosellas

Galahs

Kookaburras

ACEREZ is a partnership of ACCIONA, COBRA, and Endeavour Energy, which has been appointed by EnergyCo as the network operator to design, build, finance, operate, and maintain the Central-West Orana REZ transmission project.

The Central-West Orana Renewable Energy Zone (CWO-REZ) is Australia’s first officially declared REZ, covering approximately 20,000 square kilometres. It is expected to generate around 6 gigawatts of renewable energy, powering more than 3 million homes and attracting billions of dollars in investment. The REZ will connect large-scale solar, wind, and energy storage projects to the grid, providing long-term economic benefits for regional communities, including the Mudgee Region.

Mid-Western Regional Council (MWRC) engaged PwC to assess the impacts of additional population on services, infrastructure and housing as a result of State Significant Development (SSD) projects within and immediately surrounding the Mid-Western LGA (MWR LGA).

The report provides a point-in-time analysis based on the best data available to assess the cumulative impacts of additional population on services, infrastructure and housing as a result of major projects within and immediately surrounding the MWR LGA.

A series of issues were identified and potential recommendations have been developed to mitigate the impacts for each service sector. The actions and recommendations also identify longer-term opportunities and legacy projects with many focused on utilities infrastructure.

Managing the impact of State Significant Development(PDF, 3MB).

As of October 2023, 36 SSD projects were identified for development in and around the MWR LGA

More information is available at the Central-West Orana Renewable Energy Zone and in the NSW Planning documents

The ''Central-West Orana Renewable Energy Zone Transmission project Technical paper 4 – Biodiversity Development Assessment Report’’ dated September 2023 states:

Biodiversity: The overall direct impacts to PCTs and habitat for the various threatened species is estimated at approximately 1,031.63 ha.

The document lists critically endangered species that will be removed is at; ‘’576 hectares of White Box – Yellow Box – Blakely’s Red Gum Grassy Woodland and Derived Native Grassland in the NSW North Coast, New England Tableland, Nandewar, Brigalow Belt South, Sydney Basin, South Eastern Highlands, NSW South Western Slopes, South East Corner and Riverina Bioregions’’.

The key components of the project include: — a new 500 kV switching station (the New Wollar Switching Station), located at Wollar to connect the project to the existing 500 kV transmission network — around 90 kilometres of twin double circuit 500 kV transmission lines and associated infrastructure to connect two energy hubs to the existing NSW transmission network via the New Wollar Switching Station — energy hubs at Merotherie and Elong Elong (including potential battery storage at the Merotherie Energy Hub) to connect renewable energy generation projects within the Central-West Orana REZ to the 500 kV network infrastructure — around 150 kilometres of single circuit, double circuit and twin double circuit 330 kV transmission lines, supported on towers, to connect renewable energy generation projects within the Central-West Orana REZ to the two energy hubs — thirteen switching stations along the 330 kV network infrastructure at Cassilis, Coolah, Leadville, Merotherie, Tallawang, Dunedoo, Cobbora and Goolma, to transfer the energy generated from the renewable energy generation projects within the Central-West Orana REZ onto the project’s 330 kV network infrastructure — underground fibre optic communication cables along the 330 kV transmission lines between the energy hubs and switching stations — a maintenance facility within the Merotherie Energy Hub to support the operational requirements of the project.

A letter dated July 15 2025 letter and available on the NSW Planning webpage for the project refers to SODA – and that this was the first to secure a 'Strategic Offset Delivery Agreement'.

‘’the NSW Government has recently established a new conservation measure that enables eligible projects to use a SODA as a way to deliver biodiversity offsets.

The first Strategic Offset Delivery Agreement (SODA) was secured by NSW's Environment Agency Head for the Central-West Orana Renewable Energy Zone (REZ). This agreement, valued at $27 million, was with EnergyCo to secure over 14,000 biodiversity credits, which will be delivered by local landowners to offset environmental damage from the renewable energy project. This is a key step for NSW's renewable energy projects to meet their biodiversity offset obligations while also supporting local landholders.'' the poject webpage documents state

However, as with trees that are hundreds of years old and provide homes, food and critical habitat, biodiversity credits cannot be granted when and where there is no biodiversity left.

And baby birds that survive their wounds cannot be reunited with parent birds over such a large area - even if they could, where would they have a home with theirs now removed.

Upper Hunter Shire Council comments, in responses to proposal: November 6 2023, stated

1. Impacts on agricultural activities: Council notes that the construction area for the project is circa 3,660 hectares, which will be unavailable for agricultural use during construction, and that around 825 hectares of agricultural land will be permanently removed from service due to the establishment of permanent infrastructure. The Social Impact Assessment (SIA) appears to have given little weight or consideration to the social effects of the interruption of traditional agricultural activities. Mitigation measures need to be in place, and we request that the Department ensure that the landowners and the public in general have access to information and assistance through transparent and easily accessible channels.

2. Accommodation strategy The technical paper on social impacts provides a chapter on construction assessment which notes that the entire construction workforce (peaking at 1800) will be housed in accommodation camps in Merotherie and Cassilis. Council requests that further consultation is undertaken to develop a detailed accommodation strategy which addresses community concerns and outlines the methodology for construction and operation of the camps.

3.Traffic and Transport a) We note that Technical Paper 13 – Traffic and transport does not consider the traffic impacts of the project on transport routes outside the project area. In this regard, Section 5.1.5 states that construction of the project would require the transportation of large and/or heavy equipment via road that would constitute OSOM movements. The majority of OSOM vehicle would travel from the Port of Newcastle to the energy hubs via the Hunter Expressway and Golden Highway. As the Golden Highway passes through Merriwa, it is likely that construction traffic will adversely impact the efficiency and capacity of roads within Merriwa as well as impacting local amenity. At this stage, the extent of these impacts is unclear. In addition, given the number and scale of projects planned for the Central-West Orana REZ over the coming years, the material cumulative traffic and transport impacts on Merriwa could be significant. In our view, further investigation of the potential cumulative traffic and transport impacts is warranted including an assessment of the capacity of Merriwa’s main street and potential impacts on local roads that are currently used as a OSOM heavy vehicle bypass. b) We note that there are several local roads that form part of the construction routes that have not been quantitatively assessed, given that they would primarily function to provide access to the transmission lines’ access gates only (Appendix A of Technical Paper 13 – Traffic and transport). Construction vehicles utilising the transmission line access gates would typically be limited to 32 vehicles per hour (12 light vehicles and 20 heavy vehicles) during the peak period. Technical Paper 13 states that these low additional demands (an arrival of approximately one vehicle every two minutes) are not likely to adversely impact the performance and capacity of the road network. These roads would be subject to the routine road condition inspection discussed in Section 5.2.6. Council is concerned that the increase in vehicle movements, particularly heavy vehicles, on local roads is significant and will adversely impact the condition of the roads, increasing maintenance requirements and shortening the life of road pavements. As such, it is recommended that the developer be required to undertake detailed pavement investigations of local roads that form part of the construction routes to determine if upgrades are required to meet the proposed traffic loadings. In addition, Council requires assurance that the nominated local roads will be maintained by the developer, at the developer’s cost, during the construction phase of the project. c) Appendix A of Technical Paper 13 identifies Ancrum Street, Cassilis as a local road that will be utilised by construction vehicles. We note that Ancrum Street is a narrow residential street without footpaths that provides access to a local school. The street contains a 40km/hr school zone. Council is concerned that the increase in vehicle movements along Ancrum Street during the construction phase of the project will pose a safety hazard for local school children. Accordingly, consideration should be given to the implementation of local traffic management measures in Cassilis such as the construction of a footpath along Ancrum Street and the installation of flashing lights at each end of the school zone to ensure the safety of pedestrians including school children. d) Council wishes to see project consent conditions stating that the proponent must: i) upgrade local roads, bridges, grids, intersections and other related road infrastructure that will be impacted by the project and which require modification in the reasonable opinion of Council, in accordance with plans approved by Council, prior to any project construction work commencing; and ii) if, during the life of the project, Council provides evidence of significant increases in traffic volumes or vehicle types on other roads in the locality that can be directly attributable to the project, the proponent agrees to reach a negotiated settlement with Council to provide additional funds for road repair, maintenance or upgrade works.

4. Community Engagement The community has expressed its disappointment that there were no drop-in sessions regarding the EIS in Cassilis, despite a number of social impacts on the Cassilis community being given a high to medium rating. Overall, there has been very little consultation with the Cassilis community despite the engagement requirements specified in the SEARS.

5. Waste generation Council has very limited capacity to accept waste in the project area within Upper Hunter Shire. We request that a detailed Waste Management Plan be prepared in consultation with Council staff prior to the start of construction. We trust the above comments will be given due consideration by the Department in its assessment of the proposed development. Please do not hesitate to contact Mathew Pringle, Director Environmental & Community Services, should you have any questions regarding the content of this submission.

Greens MP and spokesperson for the environment Sue Higginson said “I am so sick of the State Significant Development pathway and the defective biodiversity offsets system being used as a battering ram to push all kinds of development through the planning system at nature’s expense, and it’s tragic that we now add renewable energy infrastructure to the list. It doesn’t have to be like this, the fact is the Minns Government has chosen it to go like this,”

“The destruction of critical habitat and tree cover we are seeing now in the Central Orana REZ is just the beginning and it’s just not necessary. Mid-West Regional Council had been working tirelessly with the developer ACEREZ to find a different pathway that would not require the removal of 670 habitat trees, but the developer and the NSW Government have essentially ignored them,”

“The developer has quite literally bulldozed past environmental protections and massacred the habitat of threatened species, and the best they can offer in response to questioning is a media release about biodiversity offsets,”

“The biodiversity offset system is broken and has been for a long time. It is so broken that it allows habitat destruction at such a scale that injured baby birds are filling up vet hospitals across the region. The Minns Labor Government had the chance to fix the offsets system last year and it chose not to. I moved amendments to the biodiversity offsets laws, and with the Minns Labor Government we had the numbers to get better laws for nature, but they chose not to. I am afraid things are going to get worse, not better.”

“We know the biggest environmental threat we face is climate breakdown and this is why we are transitioning to renewables, so to destroy nature in the name of protecting nature doesn’t square. NSW Labor’s approach risks undermining public confidence in the transition and jeopardising the urgent need for climate action,”

“Premier Chris Minns has an opportunity to demonstrate leadership here, to sit down with the community and to demonstrate how we can get renewables right. Governments need to accelerate the renewable energy transition, but that involves having strong safeguards for nature and for communities in place,” Ms Higginson said.

Planning Minister Paul Scully who was acting Minister for Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Heritage during Ms Sharpe's absence, told the ABC:

"Building renewable energy projects and transmission infrastructure is about keeping the lights on, but it's also about driving down emissions to reduce the impacts of climate change," Mr Scully said.

"But the photos are upsetting — no one wants to see birds displaced."

Residents and people across Australia don't consider this 'birds being displaced' and have called for the baby bird-killers to be charged.

Many consider the only reason this process was decided on is due to money and maximising the destruction on the environment to minimise the cost for the developers - especially since so many stated for so long there was another route directly beside it which not have required the destruction of so many ancient trees and the baby birds within them.

Just as flat, but treeless, this could have been the chosen route.

''Who cuts down trees during nesting season?'' predominates among the backlash.

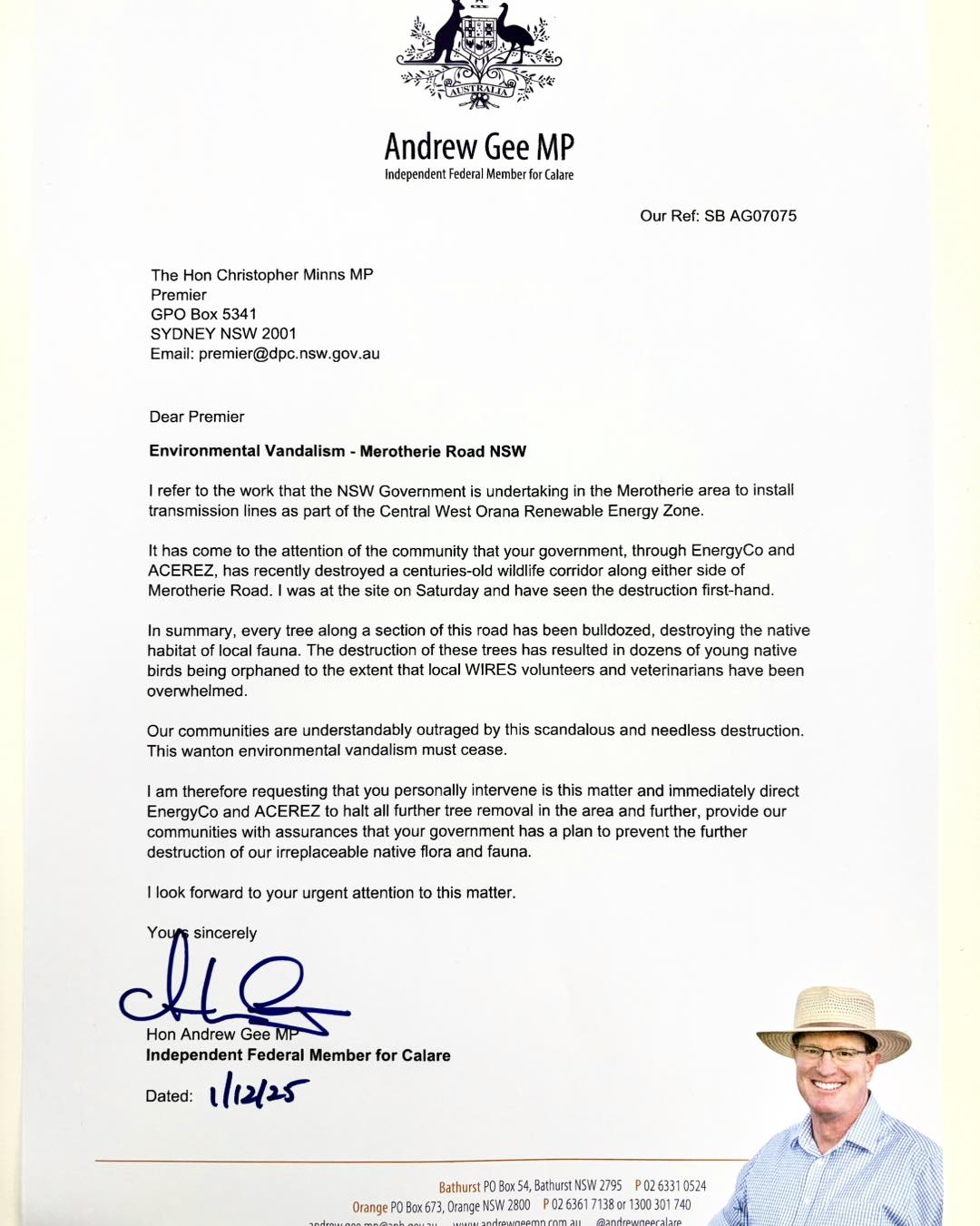

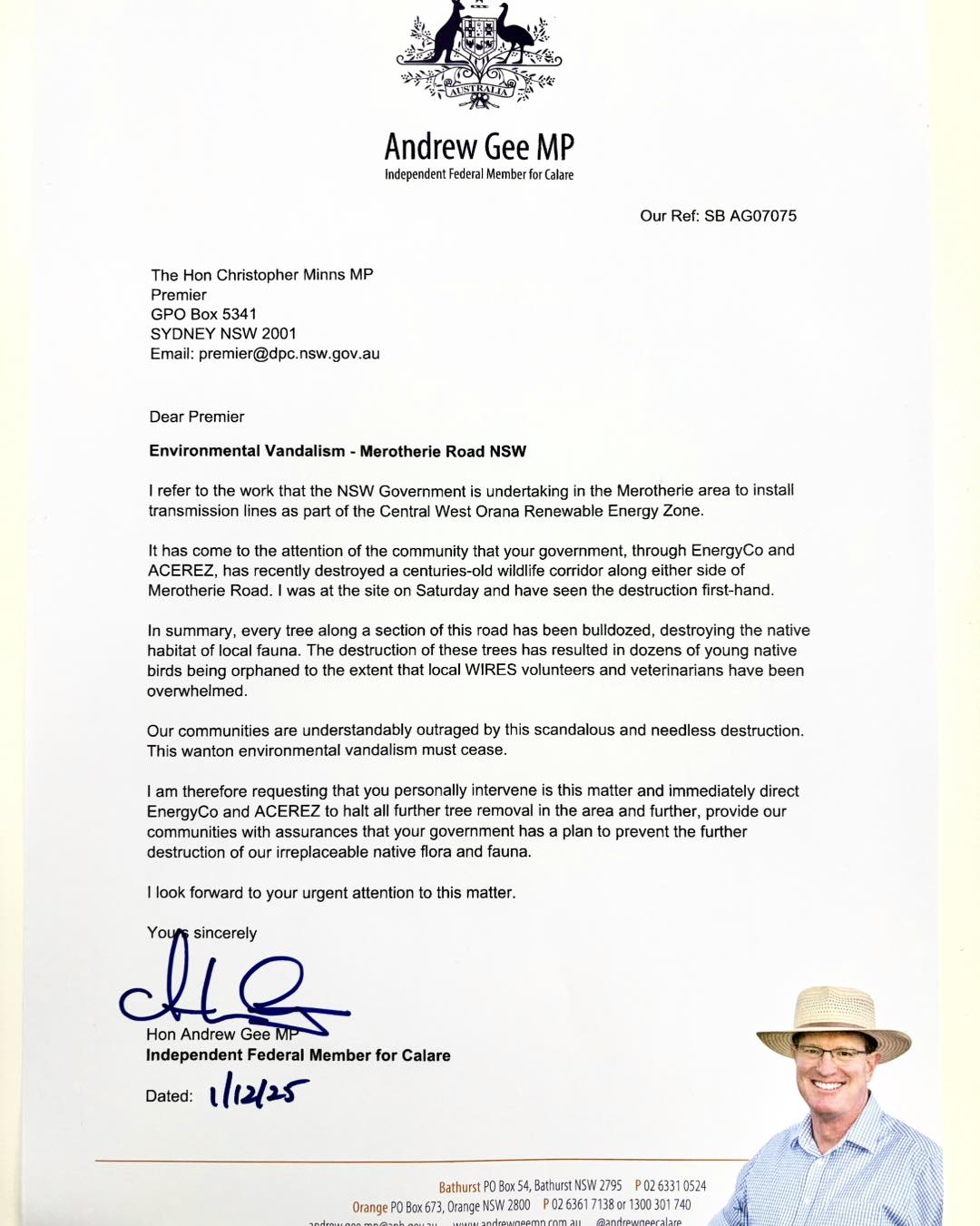

Former Nationals MP, now an Independent, Andrew Gee, has shared a letter penned to the Premier on this matter:

![]()

.jpg?timestamp=1765592323370)

.jpg?timestamp=1764993307704)

.jpg?timestamp=1764991123146)

.jpg?timestamp=1764991332007)

.jpg?timestamp=1764991903407)

.jpg?timestamp=1764992336381)

.jpg?timestamp=1764993446785)

.jpg?timestamp=1764992057606)

.jpg?timestamp=1764992870022)

.jpg?timestamp=1764993858922)

.jpg?timestamp=1764994273755)

.jpg?timestamp=1764990021353)

%20(1).jpg?timestamp=1675893929686)

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

.jpg?timestamp=1764996539556)