Community Concern As Another Tree Up for Destruction by the Council - Doubling of prior Bassett Street Mona Vale DA proposal under NSW government SSD's provides stark illustration of impact on local environment of laws written 'for developers' - Community Objections Being silenced or Ignored

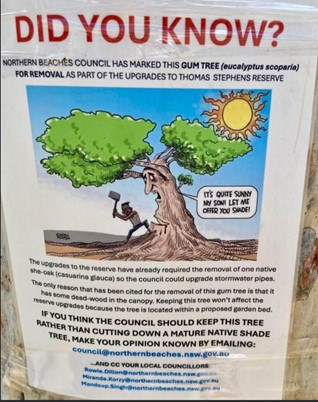

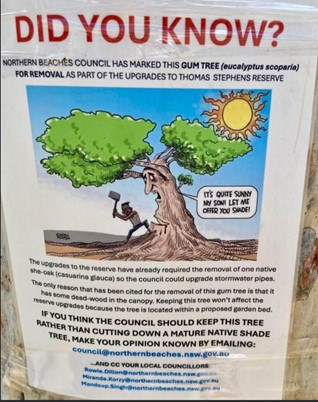

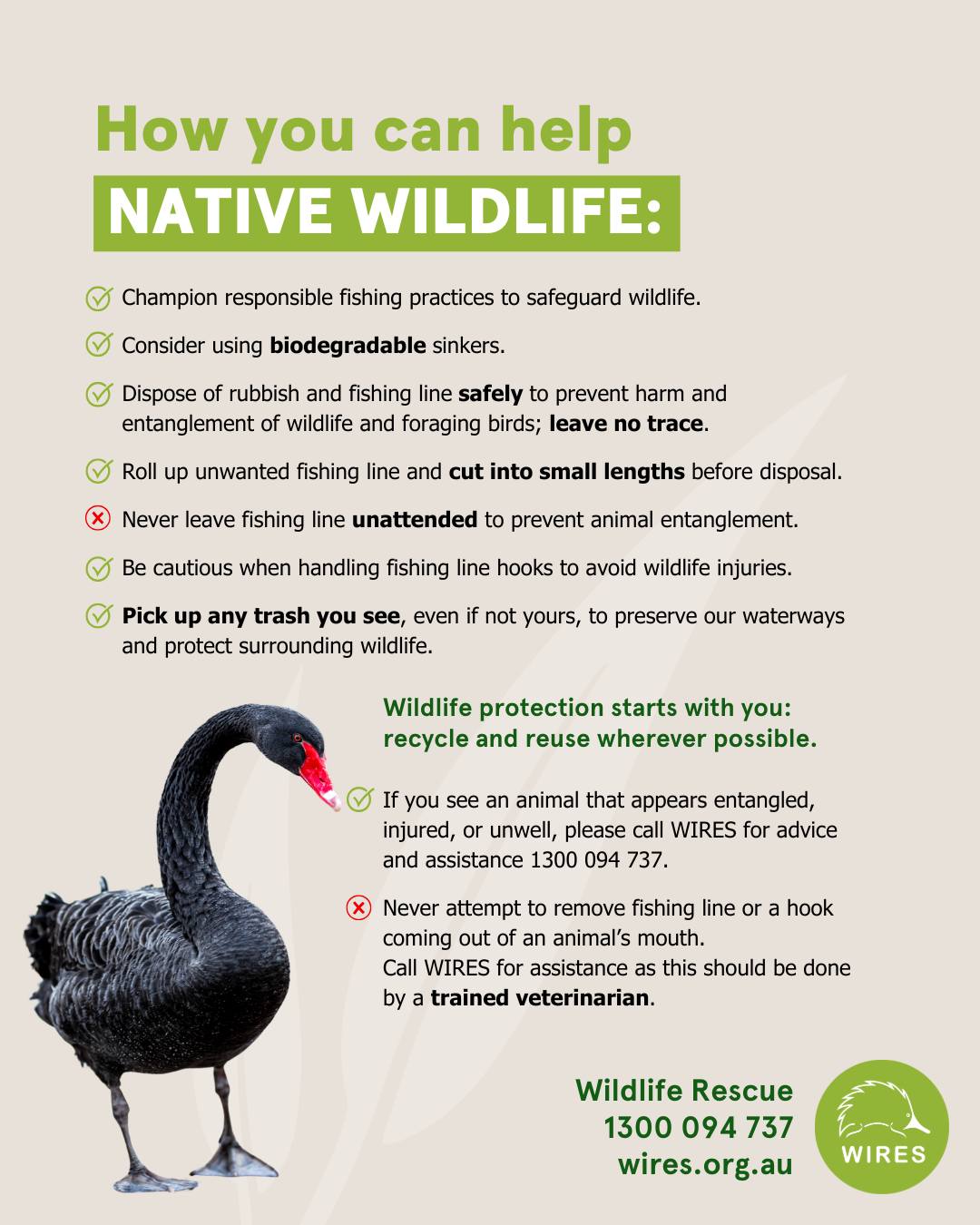

Pittwater residents are concerned about the Eucalyptus Scoparia, currently under consideration for removal at Church Point’s Thomas Stephens Reserve, by the Northern Beaches Council. Notice of this removal was made available just before Christmas. The many community objections are a push back against the continuing removal of trees by the council in Pittwater and none being planted to replace these.

Staff provided the following response before Christmas:

"The landscaping component of the Thomas Stephens Reserve project is scheduled to commence in February 2026. At that stage, once pavers and associated infrastructure are removed, Council will undertake further investigations into the health of the tree. The outcome of these investigations will inform the appropriate course of action."

Eucalyptus scoparia (Wallangarra White Gum) is known to have issues with branch failure and, while not cited among the most notorious "widowmakers" like E. camaldulensis (Red River Gum), they are susceptible to significant structural issues in urban settings, especially if their root system has been compromised by encroachments.

However, residents are asking why - given the arborist’s report does not identify any significant risk from it - is yet another tree that is food and habitat for wildlife, and shade for humans, slated for killing by this council.

Residents who have lodged a complaint or protest against its removal state they have been assured by councillors nothing would happen to it over January - but it's almost February and with the council's very poor record on looking after the Pittwater environment, and the loss of trees on every street and every playing field through the council removing them continuing, and no replacements being planted despite a 'tree plan' being passed that states in black and white they will be, the push back against south of Narrabeen Bridge 'town planning' persists in Pittwater - even for Notices made when it is assumed locals have 'clocked off' for a break and may not.... notice.

Residents point out with each of these incidences the difference between the Warringah-style council, refashioned into a 'Northern Beaches Council', and their own Pittwater Council grows.

They are calling on the still in place Pittwater Council LEP and DCP to be observed - just as the council is spending Pittwater ratepayers money to defend the same in the former Warringah council area.

See: Council Appeal on Oxford Falls Seniors DA Successful: Errors on Questions of Law Grounds

And to cease passing an environmental and social destruction of Pittwater- which many state is actual 'policy' under the NBC.

See: Killing of Ruskin Rowe Heritage Listed Tree 'authoritarian' or Council proposal to turn Boondah Reserve into a Sports Precinct: Consult feedback closes Nov. 23 or Northern Beaches Council recommends allowing dogs offleash on Mona Vale Beach or Community Concerned Over the Increase of Plastic Products Being Used by the Northern Beaches Council for Installations in Pittwater's Environment

One Mona Vale resident, Richard W., stated:

''I am astonished that council is proposing to remove the entire tree pictured below purportedly because it has dead wood in its canopy.

Why not simply prune the dead wood and otherwise leave the tree as it is?

Would you please register my objection to this senseless destruction.''

The incessant removal of mature hollow bearing trees is showing up in birds that require these now being homeless, and without shelter during the rain. Seedlings and small trees, even fast growing species, are no replacements for trees that have taken 50-100 years and more to mature to where they provide homes for wildlife:

.JPG?timestamp=1769332094592)

homeless soaked Rainbow lorikeets, January 17-18 2026, Careel Bay

.JPG?timestamp=1769332207212)

Community Being Silenced

Anna Maria Monticelli, Secretary of Protect Pittwater, applied and was denied 3 minutes speaking at the last Public Forum the Northern Beaches Council held as part of council meetings in December 2025. Her Address articulates these ongoing concerns of the Pittwater community, many of whom have dubbed the NBC just another version of Warringah Council, still pulling millions out of Pittwater to spend in Warringah while laying down concrete where it's not wanted, putting in park benches on corners from which to view traffic, and plastic grass into known flood zones - just to up the kinds of pollution flowing into the estuary or onto the beaches every time it rains - and even as these materials are being installed.

In recent months residents have seen both the Public Forum and Public Address opportunities being excised by members of political parties or lobbyist groups to express their opinions, and were becoming increasingly frustrated these are being used in this way.

The Public Forum provided an opportunity for residents to speak on any matter. The Public Address provided an opportunity for residents to speak on Items listed in the Agenda of council meetings, limited to two for and two against.

Under new Code Meeting practices passed by the council at the December 2025 meeting both the public forum and public address have been removed from council meetings. The NSW Office of Local Government's Model Code of Meeting Practice for Local Councils in NSW for 2025 states these can still be held directly before a council meeting.

The document reiterates:

4 Public forums

4.1 The council may hold a public forum prior to meetings of the council and committees of the council for the purpose of hearing oral submissions from members of the public on items of business to be considered at the meeting. Public forums may also be held prior to meetings of other committees of the council.

4.2 The council may determine the rules under which public forums are to be conducted and when they are to be held.

4.3 The provisions of this code requiring the livestreaming of meetings also apply to public forums.

In the governments' FAQ's it is stated:

'The public forum provisions are now mandatory but leave it to councils to determine whether to hold public forums before council and committee meetings'

The council interpreted this as meaning for the Public Address - ''public forums may not be held as part of the council meeting for hearing submissions on items of business on the agenda for the meeting'' - and that the Public Forum aspect, to speak on any matter, is now gone.

Under Appendix 1 of the council's draft document on Public Forum lists, among its items, 'Speakers may not make defamatory statements' (which had been a part of this platform in the last few ordinary council meetings), but no provision for residents being allowed to own this platform had been made.

Appendix 1 of the NBCDraft document listed, among other items:

A1.6 To speak at a public forum, a person must first make an application to the Council in the approved form. Applications to speak open when the business papers are published and must be received by 5pm on the business day prior to the date on which the public forum is to be held. Applications must identify the item of business on the agenda of the Council meeting the person wishes to speak on, and whether they wish to speak ‘for’ or ‘against’ the item.

Note: The Chief Executive Officer or their delegate may refuse an application to speak at a public forum where the application does not meet the outlined requirements or there is a genuine and demonstrable concern relating to the applicant or their dealings with the Council or their intentions.

A1.7 To speak at a public forum, a speaker must attend in person.

A1.8 Legal representatives acting on behalf of others must identify their status as a legal representative when applying to speak.

A1.11 Speakers must not digress from the item of business on which they applied to speak. If a speaker digresses to irrelevant matters, the chairperson is to direct the speaker not to do so. If the speaker fails to observe a direction from the chairperson, the chairperson may immediately require the person to stop speaking and they will not be further heard.

A1.12 A public forum should not be used to raise questions or complaints. Such matters should be forwarded in writing to the council where they will be responded to by appropriate council officers.

Similarly, all councillors were to be limited to speeches of two minutes during the meetings, unless they had proposed a Motion. A ban on photography during meetings would also be extended to before and after, “whilst in the vicinity of the meeting location”.

“Cutting speeches to two minutes might be a great relief for some, but the loss of those 150 words might prevent someone from explaining the intricacies of a complicated issue or describing a particularly pertinent example.'' Cr. Korzy said in 2024

“Meetings often run from 6pm to 11.30pm, with many of us arriving home well after midnight, and I would dearly love to see them shorter. We’re all aware they deteriorate after about 9pm with participants getting tired, niggling at each other across the floor and losing concentration.

“However, the proposed solution, based on the idea of making meetings more efficient, will add to the slow curtailment of democratic debate.

“The root of the problem is that the council unavoidably has too much business on its agenda, due to its size since the forced amalgamation, and some councillors’ antics delay progress through the agenda. The open-ended ban on photography is also an incursion on democracy, and a nonsense when the council itself screens the meetings online. Councillors and members of the community would be prevented from focusing the lens on those attending, even outside the chamber, which would limit anyone snapping photos showing numbers of supporters for any issue.”

Although some Councillors have been calling for years for two council meetings each month in order to adequately deal with every Item listed rather than seeing these bounced over to the following month - especially those Items of import to the community - the once a month meeting and the bouncing forward persists.

At the December 16 2025 council meeting it was resolved to:

''Establish a monthly community engagement forum, separate from the public forum referred to in clause 4 of the Code of Meeting Practice, to be held on the same evening as that public forum, for Councillors to hear from the members of the public on items not on the Council meeting agenda, on a trial basis for 6 months.''

The council also voted to 'Delete the following clauses: i. 11.5, 11.6, 11.7 and 11.8' and 'Note its opinion that the amendments to the draft Code are not substantial and it may adopt the amended draft Code without public exhibition as its code of meeting practice.'

The changes commenced as of January 1 2026.

A Notice of Motion to Rescind Council's Resolution made on 16 December 2025 in respect of Item 9.2 Outcome of Public Exhibition - Draft Code of Meeting Practice has since been lodged for the February 17 2026 council meeting - the first of a whole eleven for the year 2026.

Ms Monticelli's Address, unheard anywhere else, is:-

What the Northern Beaches Council has never understood is that their role is to represent us, not shut us up.

The council’s “have your say” campaigns amount to little more than PR exercises. They disregard genuine community input, patronise residents, and fuel frustration and anger.

Local democracy only works when communities have a genuine voice. Pittwater’s voice has been politically silenced since amalgamation.

We have 3 councillors in the Northern Beaches Council out of 15.

When the vote is 12 against 3, Pittwater loses every time.

When the vote is 12 against 3, responsible development rules for Pittwater loses every time.

When the vote is 12 against 3, our environment loses every time.

When the vote is 12 against 3 a community’s confidence in democracy loses every time.

Simply put - Pittwater always has a minority voice.

The 12–3 vote structure reinforces growing calls for de-amalgamation with many residents saying they no longer feel represented by the Northern Beaches Council.

What we have is not meaningful representation. It leaves people feeling side-lined in decisions that directly affect them. Pittwater council had 9 councillors all living in Pittwater.

The Pittwater community is not seeking special treatment: what we are seeking is appropriate recognition that our area is ecologically and geographically unique and cannot be governed by the same metropolitan development controls as other parts of Sydney.

The current blanket approach to development which circumvent local environmental limits, threatens our environment, our lifestyle and our safety. In particular the danger of pushing more people into an already crowded and confined fire zone.

A recent report co-authored by the former NSW fire commissioner, Greg Mullins, warns that what happened in the 2025 Los Angeles fires, will happen here. The report’s findings were a “wake up call”, he said.” “If you live in suburbia and think bushfires don’t concern you, think again.”

Parts of Sydney, like the Northern Beaches, Penrith and the Blue Mountains, were a “ticking timebomb” he said, with massive fuel loads built-up after years of rain.

“I know it’ll scare people,” he said. “But I hope they get past that and [say] we have to take action.”

Pittwater is on a peninsular. It has one main road in and one road out with narrow winding streets already congested with all the current ongoing-development.

It is inevitable congestion will only get worse, particularly when developers start targeting all our R2 and R3 zonings across Pittwater (which permits development consistent with residential zones right across Sydney.) Unfortunately NBC does not give proper consideration to the Pittwater Wards’ different situation.

And If Pittwater is governed like the rest of Sydney, it will be developed like Sydney.

Developers will flock here because Pittwater is a place where they can maximise their profits. Pittwater is environmentally unique and it must be protected and governed differently.

When the experts tell us terrible fires will happen here, we cannot blindly ignore them despite what politicians and urban planners say. Forcing more people into a high risk bush fire zone is a recipe for disaster.

If an expert such as Mr. Mullins is correct, one day soon, Pittwater will experience an inferno unprecedented in its history. Cars will be gridlocked on the Bends and on Barrenjoey Road. Lives will be lost and property destroyed. Fire trucks and emergency services will be immobilised in traffic.

We must stop overdevelopment that threatens public safety and start paying attention to the warning signs around us. The evidence is already here.

We need our voices heard:

- We need to fight the State government planning rules that endanger lives, property and our environment.

- We need to take control and leave the Northern Beaches Council, re-instate a Pittwater Council.

- We need ACTION NOW before it’s too late.

- Protecting Pittwater with its own council is not radical—it’s responsible.

Anna Maria Monticelli

Secretary Protect Pittwater

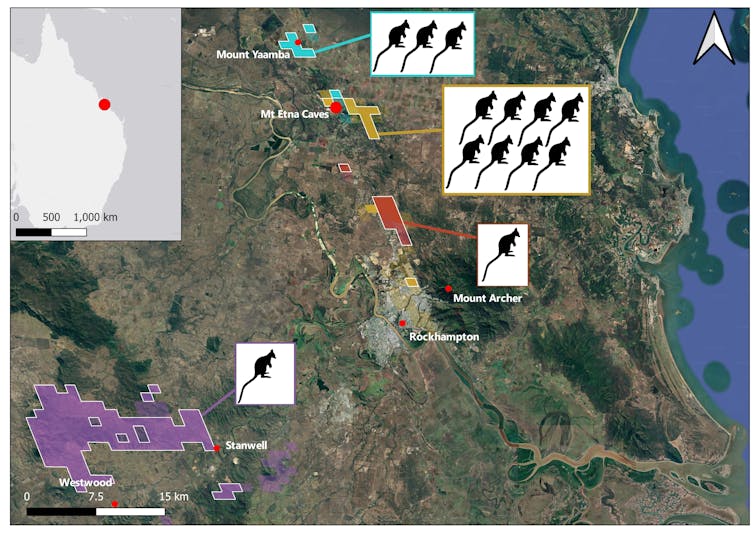

State Government's SSD's Have Developers Doubling Proposals

Ms Monticelli's Address resonates even further with Pittwater residents in view of the prior state government and council designation for places such as Mona Vale, which has only been made more stark by the current state government's SSD designation for half the suburb.

One example is the change for a September 2022 decision by the previous Coalition Government appointed Sydney North Planning Panel to approve a rezoning review request made that sought to amend the Pittwater Local Environmental Plan 2014 to:

- Rezone properties 159-167 Darley Street West, Mona Vale from R2 Low Density Residential to R3 Medium Density Residential to facilitate the redevelopment of these sites for medium density residential housing, and

- Amend clause 4.5A of the PLEP 2014 to remove its applicability to the subject site to provide a diversity and mix of housing.

Under the current state government's State Significant Development (SSD)

changes a new proposal for the same has now been put forward for 82 dwellings, doubling the impact, and razing the streetscape and blocks of all trees in a known flood zone.

Those living in similar developments further up the hill, with underground carparks, state they have had several insurance claims since their builds' completion, as there have been flooding problems and ongoing subterranean moisture. In fact, everywhere such developments have been allowed, on known water courses, over old creeks and swamplands, those buying into them soon find they have bought something they will pay to repair for the term of their living there.

On 15 April 2025, the amendment to the Pittwater LEP 2014 was finalised, which involved the following key changes to the site’s planning controls:

- Rezone the site from Zone R2 Low Density Residential to Zone R3 Medium Density Residential.

- Include a clause under the Pittwater LEP 2014 to require a 5% affordable housing rate to apply to the total gross floor area.

- Include the site on the Biodiversity Map and for clause 7.6 biodiversity of the Pittwater LEP 2014 to apply.

- Remove the site from the Minimum Lot Size Map consistent with all land zoned R3 Medium Density Residential in the Pittwater LEP 2014.

Following LEP finalisation, it was noted that the final LEP Amendment did not achieve the underlying objectives or intent of the site-specific rezoning, which was to abolish the restriction of dwelling density control applicable under Clause 4.5A of the Pittwater LEP for all R3 zoned land. Colliers Urban Planning (formerly Ethos Urban), on behalf of the Applicant, made representations to DPHI in May 2025 raising concern for the continued application of this dwelling density control, and its effects on the application of applying Chapter 6 (Low and Mid Rise Housing) under the State Environmental Planning Policy (Housing) 2021 (Housing SEPP).

On 5 September 2025, amendments to the Pittwater LEP 2014 were made and included an amendment to Clause 4.5A(3) to identify that this clause no longer applies to the subject site.

Under the Northern Beaches Section 7.12 Contributions Plan 2024; Contributions will be provided in accordance with the Northern Beaches Section 7.12 Contributions Plan 2024, which will apply a levy of 1% of the total EDC as it is more than $200,00.

The SSD will also become part of Northern Beaches Council’s Affordable Housing Contributions Scheme; In addition to the Section 7.12 levy, contributions will be provided in accordance with Council’s Affordable Housing Contributions Scheme, which will apply a rate of $19,658 per square metre.

The EIS states '26 trees are being retained on site and 58 trees are proposed to be removed; however, these will be appropriately supplemented by the planting of 84 new trees in their place, equating to a net increase of 26 trees on the site.'

However, many 'new' trees planted to gain passage of a DA are then ripped out soon after being counted - and as residents continue to point out, you cannot replace an established old tree with a new one and think they are the same.

Regarding being in a known waterflow zone, the proponents state:

''The proposal adequately manages the overland flow path on the site and associated flooding risks. On-site stormwater detention and treatment systems will be designed in accordance with the relevant standards.'

The Total Development Cost (Plus GST) for Non-SSD/SSI is tabled as being $ 104,891,540.00.

Both the council and state governments continue to approve such DA's, disregarding the knowledge and research that informed those Local Environment and Development Control Plans and signalling these will all be approved no matter how many objections are lodged by those with lived experience of these places.

John David, Convenor of newly formed residents group, SOS Save Our Suburb Mona Vale, points out:

''On Tuesday January 20 2026 the EIS for the SSD proposal in Darley Street West was made available and submissions can be lodged with the State Government.''

We get only 14 days from today until Tuesday 3rd of February 2026 to

- read the proposal,

- make a considered assessment of our objections (or support),

- and write & submit our views.

This short period includes the Australia Day holiday weekend and in my view is a further cynical attempt by both developer and State Government to sideline the community to as much as possible.'' John said, explaining further:

- Letters advising "the community" went out to neighbours only.

- The entire proposal is 2361 pages long.

The State Government has telegraphed theses changes to developers for over a year before they became law.

- the developer gets a year to prepare their proposal;

- the State Government gets 270 days (the average assessment period) to do their due diligence;

- the community gets 14 days to submit their views!

''There is nothing about this process that suggests the State Government or the developers have any wish to dignify the rights of residents of this suburb with anything apart from a passing interest. We are invisible and unimportant in their minds.''

''The cynical exercise of putting this brief "exhibition period" around the Australia Day holiday is no accident. It demonstrates what little respect the developer AND the State Government have for your concern. Do not let them bully you.'' Mr. David said

The SSD is now for a 5-storey with 3 levels of underground carparking, forcing a dam of concrete into the earth through which waters move and in which pipes containing old creeks have already been placed.

Why settle to make $42 million when you can make $100+ million?

The destruction of Pittwater, tree by tree by council and state government, in flood zone by flood zone, continues.

Residents state that is: ''All for the benefit of profiteers who will be long gone when the community picks up the tab for increased costs to mitigate, through rate rises equating currently to an extra 16 million dollars, what is already occurring in these places.''

The sentiment is that 100 years after the first 1920's a 'for developers policy' of razing the North Narrabeen watersheds, all the way along the Barrenjoey peninsula, and a total disregard for the problems created, will now also place humans in jeopardy, or at best, reduce their standard of living, to live in a place with shaded cooler paths and pristine waters, to zero.

Flooding across Pittwater, including Mona Vale and Bayview over January 17-18 2026, would indicate the build-up of hard structures on the surface, and underground construction of concrete carparks that are 'dams' on the flow of water through the earth or along the historical creek channels, are effectively already exacerbating a landscape not meant for these sorts of developments.

NSW SES Warringah / Pittwater Unit members clearing a blocked drain on Pittwater road at Mona Vale which was making the flooding worse. Photo: NSW SES Warringah / Pittwater Unit via FB

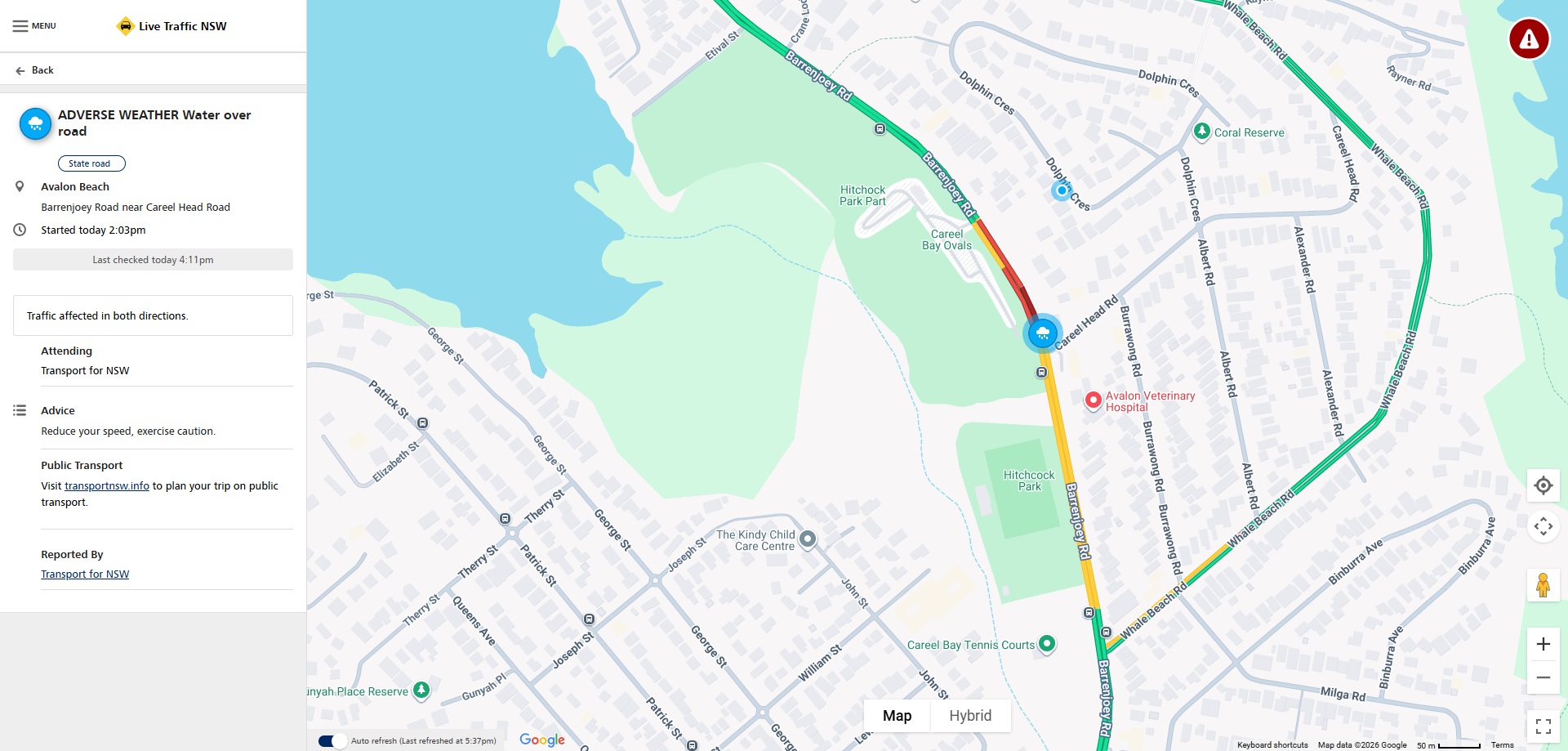

At Careel Head Road, North Avalon, where the council spent so much of a

government grant to put in a pavement on plans for the same that it was decided not to put in the guttering along a whole section, or the originally designed retaining walls leading into the intersection.

The road was flooding on January17-18 2026, effectively blocking any safe passage for emergency services needed further north. This has been occurring at this intersection since time immemorial, excepting in recent years this has been happening more frequently and flooding higher and higher and further each time, with the whole flat stretch south and north of Careel Head road, to Etival street and beyond, 1000 metres in length, now regularly being covered in water each time it rains.

.JPG?timestamp=1658000364459)

July 2022: Corner of Barrenjoey Road and Careel Head road floods in rains, with some drivers crossing double lines on that corner and into lane of southbound vehicles

Careel Head-Barrenjoey Road section, January 17 2026. Photo: Adam L'Green/FB

At this junction it took almost a year to fix just one of the drains.

At 8am on August 2nd 2022 a Council worker erected these barriers around one of the drains. The Council person, with an attitude where they were apparently deigning to reply, stated to the Pittwater Online employee who spotted the barricades going up that ''the work would be attended to as soon as someone was able to do the work''.

Saturday June 3, 2023 - barricades still in place around this still unfixed drain

There were a few more floods along this section in between that lapse of almost 12 months and several since.

As residents of Pittwater begin to eye May 2026, 10 years since 'Warringah council' was forcibly imposed on them once more by the previous Coalition government and through the campaign of the then Warringah council to be in charge of everything, and the current state government's apparent stone-deafness to the impacts their 'housing policy' will cause, the appetite for Pittwater Council to be returned, and for representation that is For, About and BY Pittwater, has grown, not diminished.

Related:

159-167 Darley Street West, DA is for 5-storey buildings with 3-storyes of carparking under them - he trees seen here, holding the earth in place, will be removed

screenshot from CK video of the Ruskin Rowe gum tree trunk - killed by council decree

![]()

.jpg?timestamp=1683335071744)

%20(1).jpg?timestamp=1675893929686)

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

Shorebird Identification Booklet

Shorebird Identification Booklet