Synthetic grass fragments are increasingly prevalent microplastics in waterways across Metropolitan Sydney: Report finds Microplastics Have tripled in Sydney's waterways in three years - Manly Cove's 'very high' reading - NSW microplastics report 2026

A report based on seven years of citizen-led shoreline surveys has found that microplastic pollution is surging in Sydney's waterways.

The report names Port Hacking in Sydney's south, North Harbour, and lagoons on the northern beaches, such as Narrabeen and Dee Why, as the city's worst hotspots for microplastics.

AUSMAP's shoreline monitoring also provides some of the first site-specific evidence of an increase of synthetic grass fibres accumulating in Metropolitan Sydney waterways.

The highest average concentration recorded to date was at Tower Beach (Gamay/Botany Bay), where up to 2,500 blades per m² were recorded in 2024. Local stormwater inputs, rainfall patterns, and nearby synthetic grass fields in the Botany Bay region likely contribute to the high and variable amounts seen at this site.

Synthetic grass installations are now commonplace across Australia, appearing everywhere from community and elite sports fields to school playgrounds, party boats, residential yards and public landscaping.

These surfaces have been associated with a range of concerns, including surface temperatures reaching up to 75 °C on hot days, increased player injury risk, reduced biodiversity, and intensified urban heat, particularly in Sydney's Western Suburbs.

This increasingly popular plastic product has the potential to release microplastics into surrounding drains, parks, and waterways, contributing to a growing and largely unmanaged source of urban plastic pollution.

The Northern Beaches Council has been installing this product across Pittwater in playgrounds and parks and wetlands, in known flood zones, without consultation, without updating Plans of Management to state the product has been installed in these environments, for at least 5 years.

Microplastics pollution data

AUSMAP’s ongoing monitoring at Manly Cove has revealed consistently high levels of microplastic pollution, marking it as one of Australia's significant hotspots. Since mid-2018, AUSMAP researchers and community members have collected over 60 samples from Manly Cove, building one of the most comprehensive datasets on microplastic pollution in Australia, and potentially worldwide. This data reveals concerning trends that highlight the severity and persistence of microplastic contamination at this site.

The microplastic levels at Manly Cove frequently fall into the “High” (251-1,000 microplastics/m²) or “Very High” (1,001-10,000 microplastics/m²) categories on AUSMAP’s pollution scale, with a peak concentration recorded at 4,097 microplastics/m² in July 2024. This consistently elevated pollution suggests that Manly Cove is experiencing ongoing contamination from plastic debris.

Some of the highest recorded averages were in lagoons or smaller waterways (e.g. Dee Why Lagoon, Curl Curl Lagoon, Port Hacking and Manly Lagoon) suggesting these smaller, low-flushed estuaries accumulate microplastics. Additional sampling is needed to verify some of these findings.

In contrast, locations such as Middle Harbour, Pittwater, Southern Beaches and the Hawkesbury River, where the water is flushed by tides and floods, recorded low concentrations (<50 MPs/m²), and the Cooks River remained below hotspot thresholds despite its heavily urbanised catchment, and clear records of runoff into all these sites during rain events.

The composition of microplastics across Metropolitan Sydney from 2022 to 2025 revealed a broadly consistent pattern across estuaries, dominated by foam and hard fragments, though a few distinct deviations due to localised influences were apparent (e.g. Lower Hawkesbury River).

For the coastal locations, there were different dominant microplastic types in each area, highlighting the localised nature of microplastic pollution. This variability likely reflects site-specific factors such as nearby stormwater outlets, beach use, coastal tourism, and ocean-driven transport. Smaller proportions of film, fibres, and synthetic grass were recorded sporadically across coastal sites, while pellets showed high variability in some sites but remained low elsewhere.

- 67 % of Sydney sites recorded hard fragments and foam as the two most common microplastic types

- 89 % of Sydney sites recorded pellets on the shoreline

The report states:

'Foam comprises the largest proportion of microplastics across most sampled Sydney locations, with several sites exhibiting overwhelming contributions from this material.

Foam specifically accounted for 74 % of microplastics recorded in Narrabeen Lagoon, 67 % in Parramatta River, 62 % in Port Hacking, 56 % in both Curl Curl and Manly Lagoons, and 52 % in Dee Why Lagoon. This reflects the widespread presence and persistence of expanded polystyrene (EPS) debris, a material that fragments readily and disperses through stormwater.

While much of this foam originates from diffuse stormwater inputs, episodic pollution events can contribute to localised spikes, which have been increasingly observed at popular Sydney beaches. An example of this was seen at Bondi Beach in December 2023, with hundreds of thousands of foam balls washing onshore likely due to a polystyrene-based pontoon incident on the northern beaches of Sydney.'

Foam, Hard fragments and Pellets were also the primary sources of microplastic pollution in the Pittwater estuary as well.

The same washes onto every Pittwater beach with each tide.

The whole NBC LGA beaches are rated as having 'moderate' pollution, indicating every area has increasing microplastics. The surveys found:

Avg. microplastic / m2 (SEM)

Pittwater

- Careel Bay - 41(13) - 3 surveys 2022-2025

- Palm Beach 11(8) - 2 -

- Riddle Reserve Bayview - 76 - 1surveys 2022-2025

- Sandy Beach Palm Beach 51(12) - 3 surveys 2018-2021

- Narrabeen Lagoon 43(7) 190 10surveys 2018-2021 1 survey 2022-2025

Dee Why Lagoon 351(118) 839 8 1

Curl Curl Lagoon 101(32) 1175 4 1

Manly Lagoon 44 5056 1 1

North Harbour

- Collins Flat Beach 106(4) 12399 4 1

- Little Manly Beach 109

- Manly Cove 631(129) 1660(332) 35 surveys 2018-2021 43 surveys 2022-2025

- Manly Cove East 342(142) 85 2 1

Middle Harbour

- Clive Park 129 - 1 -

- Echo Point Beach 14(7) 1 4 2

- Edwards Beach - 71

AUSMAP’s states the data on Manly Cove exemplifies the wider issue of plastic pollution and underscores the need for targeted actions and policies to address the root causes of microplastic pollution.

''Once microplastics enter the ocean, they are exceedingly difficult to remove, making prevention at the source the most effective solution. Stronger regulatory protections, coupled with efforts to reduce plastic use and improve waste handling, are essential to protect marine ecosystems and mitigate the long-term impacts of plastic pollution.'' the organisation states

AUSMAP - Australian Microplastic Assessment Project - is a national group of high profile environmental groups, researchers, sustainable businesses and educators. They gather crucial new data about microplastic in aquatic environments: how much is out there, where it is and where is it coming from.

Download the 2026 report 'Australian Microplastic Assessment Project (2026). Do We Have a Microplastic Problem in Our Coastal NSW Waterways? A report of Total Environment Centre. 54 pp.; - Using citizen science as a data-driven, early warning system to identify microplastic hotspots'

Plastic Grass Increasing in Aquatic Environments

Shoreline surveys by AUSMAP demonstrate the presence of synthetic grass fibres in Metropolitan Sydney waterways dating back to 2019.

Synthetic grass microplastic fibres are released from their source, such as sporting fields, residential yards, playgrounds, and landscaped areas, through everyday wear, weathering and maintenance activities. Once mobilised, these fibres can enter the surrounding environment via the stormwater network. There, they persist in sediments and along shorelines, where they can act as sponges for other environmental pollutants and be ingested by wildlife. Importantly, this demonstrates that synthetic grass materials are not confined to their points of installation but are dispersed into the wider urban environment.

Recent AUSMAP data show that synthetic grass fragments are becoming increasingly common in Sydney’s waterways. At regularly monitored locations, such as Rose Bay in Sydney Harbour, synthetic grass debris has increased approximately tenfold between 2022 and 2025, reaching over 20 blades per square metre.

Similarly, at Manly Cove, synthetic grass fragments were first detected in 2019. Concentrations have since tripled, despite natural year-to-year fluctuations.

Poulton Park was raised as an area of concern by the Oatley Flora and Fauna Society. The park consists of two synthetic fields situated next to Poulton Creek, which flows into the Georges River.

Core samples were taken at three distances (0, 4 and 8 metres) from the study sites. Results found that there were approximately 1 million pieces of rubber crumb or synthetic grass coming off those fields. These findings were presented to the local council and are being used to implement mitigation strategies.

AUSMAP completed toxicity studies to evaluate the impact of rubber crumb leachate on freshwater and marine species. Rubber crumb was leached for 18 hours. A freshwater water flea as well as larval marine mussel and sea urchin were exposed to diluted concentrations of the leachate.

Results found that concentrations of 1-3% affected 50 percent of the populations. This is likely due to concentrations of zinc which were significantly higher than the Australian Water Quality Trigger Value. Although other chemicals such as 6 PPD-q and HMMM were also recorded but further toxicity trials are needed to ascertain their impacts to local aquatic life.

Recently, AUSMAP has been working with Ku- ring- gai Council in Sydney’s north-west to quantify microplastic loss from a synthetic turf field and the efficacy of stormwater pit traps to reduce this loss. Results have highlighted that >100,000 particles of rubber crumb and synthetic grass are captured in most trap samples, representing 82% of the loss. However, sampling of the runoff water into a nearby creek found both crumb and synthetic grass to be prevalent. Key findings from this investigation highlight extreme microplastic loss from this surface that would enter the environment unabated without the presence of stormwater mitigation traps. The full impact of mitigation approaches is yet to be reported - and invariably, to date, are not common practice.

AUSMAP are calling for a 5-year moratorium on new planning and approvals for synthetic grass fields until further research and information on potential human and environmental harm from these fields is clarified.

The group are also calling for Enforcement of Australian Standards for pollution mitigation measures on synthetic grass fields and more detailed guidelines for field management to be implemented on all existing synthetic fields as soon as possible.

AUSMAP states investment in and a substantial effort into improving drainage and the condition of natural grass fields to avoid synthetic grass installation should be first choice.

They are calling on Local governments (councils) to provide a truly balanced cost-benefit analysis at the end-of-life of synthetic fields compared to those of natural turf.

Residents of Pittwater are calling on the Northern Beaches Council to consult with the community for approval where and when they have a plan to install plastic turf or plastic products, such as those now used in wharves, in the Pittwater environment area.

There are ongoing calls to either remove where it has already been installed already, especially when that is a known flood zone, wetland or the estuary, and to update the applicable POM's for these sites to state they have installed the product so these sites can be easily identified when it becomes obvious it should be removed.

Residents have pointed out that even when projects are listed under the 'have your say' section of the council website they are announcements, not consultations.

2025 reports:

Also available:

References:

1. Katrina R. Bornt a b, Joshua W. Rule a, Peter A. Novak An undocumented source of plastic contamination in sensitive estuarine environments. Marine Pollution Bulletin, Volume 211, February 2025, 117369

Highlights

- Plastic infrastructure is prevalent around the SCE, particularly decking on jetties.

- Surface degradation was evident at all sites.

- Various factors likely influence severity of degradation in estuarine systems.

- Suitability of plastic infrastructure in estuaries requires further investigation.

Abstract

The degradation of plastic infrastructure installed along estuaries and coastal environments may constitute a significant source of plastic contamination. This study aimed to determine the prevalence of plastic infrastructure and the extent of surface degradation of these plastics in a case study system, the Swan and Canning Estuary, Western Australia. The severity of cracks, chips, deformation, and material loss were used to estimate a novel degradation index for the plastic components on structures. The most common plastic infrastructure was decking on jetties, predominantly fibre reinforced (70 %) and co-polymer recycled (20 %) plastics. Degradation was evident at every site and varied across structures and plastic materials. The severity of degradation was likely influenced by a range of complex interacting factors such as structure age, and wet-dry cycling, alkalinity, and high temperatures that are characteristic of estuarine environments and known to exacerbate degradation of plastic materials. This study revealed plastic infrastructure was common in the case study system, structures start degrading during installation and may constitute a significant, and hitherto undocumented, source of plastic to these environments.

The durability of plastics, purported resistance to degradation and lower installation costs (relative to some materials) means they are often recommended over traditional materials (e.g. timber, metal and concrete) for infrastructure applications. In estuarine and coastal environments plastic is used widely for shoreline infrastructure that frequently interacts with water such as decking, walkways, pontoons, boat pen and jetty chafer posts, pile sleeves and capping, and fenders, among other uses. Shoreline infrastructure is subject to a range of degradation factors that may challenge the durability, and therefore, longevity of plastic. Laboratory testing of a commonly used plastic in shoreline infrastructure, fibre reinforced plastic (FRP), showed susceptibility to increased degradation under high ambient air temperature (>40 °C) (Wu et al., 2023), frequent wetting and drying cycles (Aiello and Ombres, 2000; Wu et al., 2023), ultraviolet (UV) radiation (Cai et al., 2018; Dong and Wu, 2019; Sasaki and Nishizaki, 2012; Zhao et al., 2017) and alkalinity (i.e. high pH rather than total alkalinity) (Bazli et al., 2016). Furthermore, abrasion and wear from foot traffic can be a significant factor in the degradation of these structures (Sabry et al., 2022; Talib et al., 2021), with the degree of severity depending on the polymer type (including fibre reinforcement), and location of infrastructure (e.g. sandy shorelines). The ongoing use of plastic in shoreline infrastructure may represent a significant source of contamination to the environment and a legacy issue for decades to come, yet there is limited understanding of the degradation and potential shedding of plastic from these structures.

This study aims to document plastic infrastructure in estuarine environments as a potential source of plastic contamination by assessing the extent of plastic use and prevalence of surface degradation, and plastic shedding in a case study system, the Swan Canning Estuary (hereafter SCE) in Western Australia (WA).

.....

To conclude, the surface of plastic shoreline infrastructure installed in estuarine environments starts degrading shortly after installation. This study did not assess structural integrity of plastic infrastructure, and therefore, they may still meet the 20–25 year structural lifespan often promoted by manufacturers. However, these structures start to shed plastic material through surface degradation far earlier than this intended lifespan. Once plastic shoreline infrastructure starts degrading and shedding plastics, it continues to do so throughout the lifespan of the product, therefore, constituting a constant source of plastic to sensitive environments for decades. In contrast to natural products, such as untreated timber, where the loss of material constitutes negligible environmental risks, contamination from plastic is known to cause long-term environmental harm (Andrady, 2011). The susceptibility of plastic infrastructure to a range of degradation factors that are inherent in the SCE and estuarine environments globally, or resulting from installation and purpose-built structures that absorb impact, would suggest they are currently unsuitable for these applications, particularly when environmental risk management is a key priority. Furthermore, the use of plastic infrastructure creates another waste stream of plastic material that will need to be resolved in the future. This work constitutes a baseline of plastic shoreline infrastructure prevalence in an estuarine environment and introduces and recognises, for the first time, these materials as another potentially significant source of plastic contamination to estuarine and coastal environments. Future investigations of differing plastic infrastructure across various environments would be beneficial in elucidating potential factors influencing degradation of such materials in these environments and provide further information on their suitability for installation in comparable circumstances. This study also intends to inform management about the potential environmental risk from contamination arising from plastic shoreline infrastructure whilst informing policy development relating to its use and ongoing monitoring.

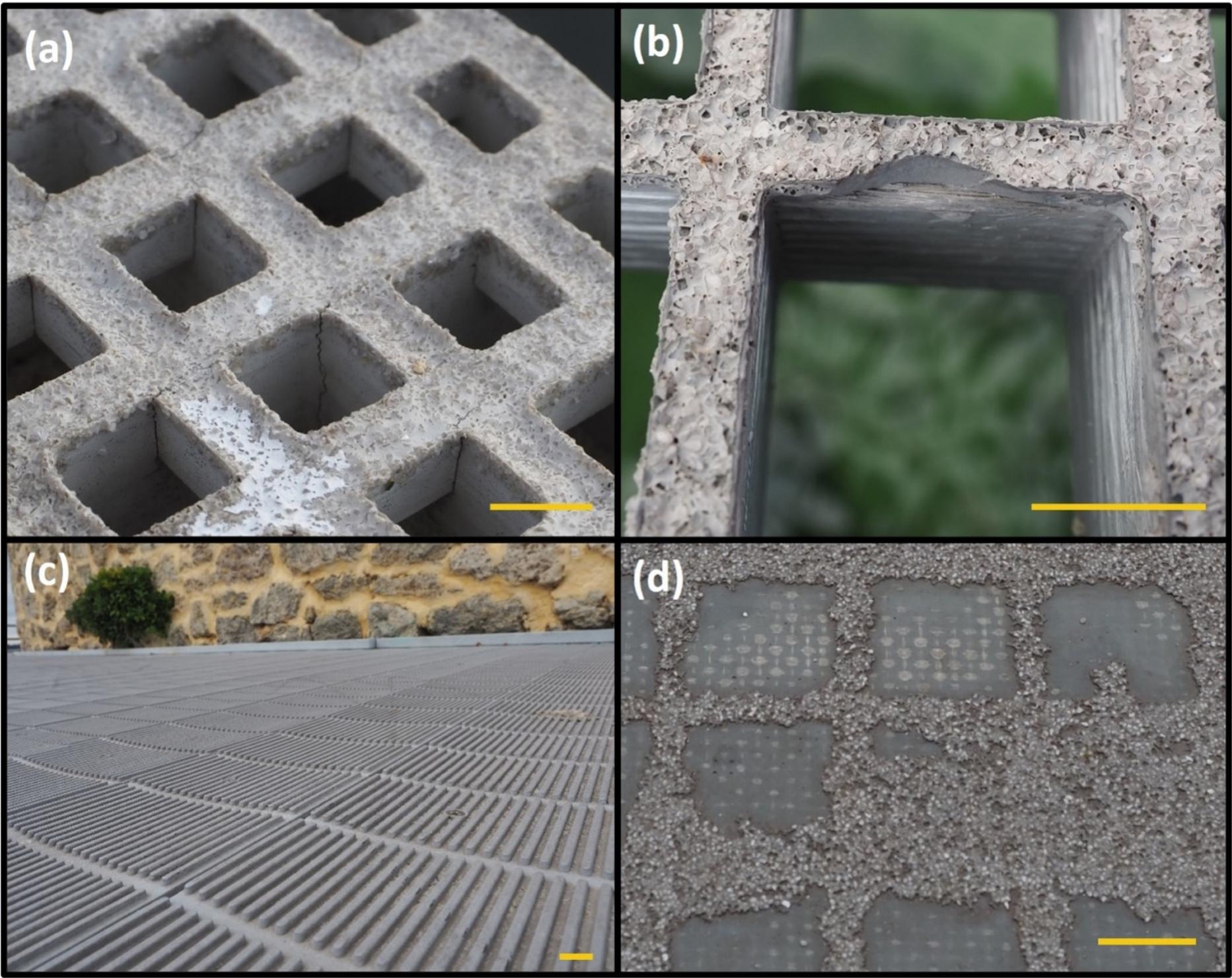

Fig. 3. Examples of each degradation criteria (a – cracking of micro/mini mesh fibre reinforced plastic, FRP); b – chipping of FRP with standard grating; c – deformation of recycled co-polymer; d – material loss on solid top FRP used for rapid visual condition assessments. Orange scale bars represent 1 cm.

2. Lourmpas N, Papanikos P, Efthimiadou EK, Fillipidis A, Lekkas DF, Alexopoulos ND. Degradation assessment of high-density polyethylene (HDPE) debris after long exposure to marine conditions. Sci Total Environ. 2024 Dec 1;954:176847. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.176847. Epub 2024 Oct 10. PMID: 39393706 at, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39393706/

Abstract

The degradation of high-density polyethylene (HDPE) in marine environments was investigated under various weathering conditions. HDPE debris were collected from coastal areas near Korinthos, Greece which had been exposed to marine conditions for durations ranging from a few months to several decades; they were analysed alongside with laboratory-manufactured HDPE specimens subjected to controlled weathering exposure. Four (4) different cases were investigated, including exposure to different conditions, namely to (a) natural atmospheric and (b) sea weathering conditions, (c) accelerated ultraviolet (UV) radiation, and finally (d) submersion to artificial seawater for up to twelve (12) months. The degradation assessment was proposed based on performed tensile mechanical tests, while the chemical/microstructural changes were assessed through Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy and Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). FTIR spectroscopy indicated the emergence of carbonyl groups, with peaks appearing between 1740 cm-1 and 1645 cm-1, which are crucial indicators of photo-oxidative degradation. Key findings revealed that HDPE specimens experienced significant (8 %) ultimate tensile strength (σUTS) only after 3 months of atmospheric exposure, while this decrease can reach up to 60 % over the period of 35 years exposure. A strong correlation was observed between the σUTS decrease between the (a) natural environment and (b) accelerated UV weathering exposure. It is noticed that 1½ month of accelerated UV exposure corresponded to similar ultimate tensile strength decrease for 6 months of natural atmospheric degradation. A linear correlation is proposed to assess the long-term materials' tensile properties degradation in marine environments.

3. Chowreddy, R.R., Fredriksen, S.B., Anwar, H. et al. Degradation behaviour of different polyethylene and polypropylene materials under long-term accelerated weathering conditions. J Polym Res 33, 45 (January 29 2026). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10965-026-04777-x

Abstract

Degradation is heavily influenced by the polymer’s molecular structure, morphology, and the presence or absence of additives. Long-term accelerated weathering experiments, lasting up to 10,000 h, were conducted on various commercial polyethylene (PE) and polypropylene (PP) resins in a Weatherometer (WOM). Dumbbell-shaped test pieces were produced from various resins, including both virgin grades with and without antioxidant additives, as well as recycled high-density polyethylene (HDPE). Throughout the experiment, test specimens were removed from the WOM at regular intervals of 2000 h and analysed for molecular weight, carbonyl index, additive content, and morphological changes. The results indicated the effectiveness of antioxidants and UV stabilisers in protecting polyolefins from significant degradation. In contrast, polyolefins with limited or no UV stabilisers and antioxidants exhibited severe degradation. The PP materials were found to degrade more rapidly than their PE counterparts. Among the virgin PE grades, low-density polyethylene (LDPE) experienced a higher rate of degradation than HDPE. Interestingly, HDPE with an adequate concentration of UV and antioxidant additives showed no signs of deterioration over the test period of 10,000 h. Notably, recycled HDPE containing antioxidant additives degraded more quickly than additive-free HDPE, possibly due to pre-existing free radicals in the recycled material. Oxidative degradation was characterised by a pronounced decline in molecular weight and a marked increase in carbonyl functionalities. Surface deterioration, especially the development of microcracks, was a clear indicator of weathering. The PE samples with microcracks demonstrated a significant drop in impact strength, suggesting that such cracks serve as stress concentrators or notches. This finding highlights the direct relationship between microcrack formation and diminished impact performance. The mechanisms of crack propagation in PE and PP resins appeared to differ, likely reflecting differences in their crystalline morphologies.

Lakeside park; the catchment claiming landfill areas back. MORE HERE

Kamilaroi Park, Bayview - from the road - rain runoff drains straight into the Pittwater estuary at the bottom of this hill

.jpg?timestamp=1765592323370)

Plastic grass installed in Avalon's Dunbar park where the creek floods during rain events - this wasn't listed as a product to be used in the Avalon Place Plan- residents were not consulted on whether they wanted this product in Pittwater. This area, where the Avalon Guide Hall once was, had been slated as a picnic table area under Pittwater Council

A plastic walkway has been installed in Warriewood Wetlands, again without consultation - once put into a marine/flood environment it becomes a pollutant, poisoning everything with microplastics - this product begins shedding pollutants as it is being installed.

at Newport Beach November 2022, a year and a half on from installation, this softfall/microcrumb area has holes in it

![]()

.jpg?timestamp=1765592323370)

smaller.jpg?timestamp=1769645602951)

smaller.jpg?timestamp=1769645638078)

smaller.jpg?timestamp=1769645668722)

mumma smaller.jpg?timestamp=1769645238812)

smaller.jpg?timestamp=1769644965301)

.jpg?timestamp=1769645711165)

smaller.jpg?timestamp=1769645775148)

.jpg?timestamp=1769645809209)

.jpg?timestamp=1769645866040)

(1).jpg?timestamp=1675893929686)

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

Shorebird Identification Booklet

Shorebird Identification Booklet

The Avalon Preservation Association, also known as Avalon Preservation Trust. We are a not for profit volunteer community group incorporated under the NSW Associations Act, established 50 years ago. We are committed to protecting your interests – to keeping guard over our natural and built environment throughout the Avalon area.

The Avalon Preservation Association, also known as Avalon Preservation Trust. We are a not for profit volunteer community group incorporated under the NSW Associations Act, established 50 years ago. We are committed to protecting your interests – to keeping guard over our natural and built environment throughout the Avalon area.

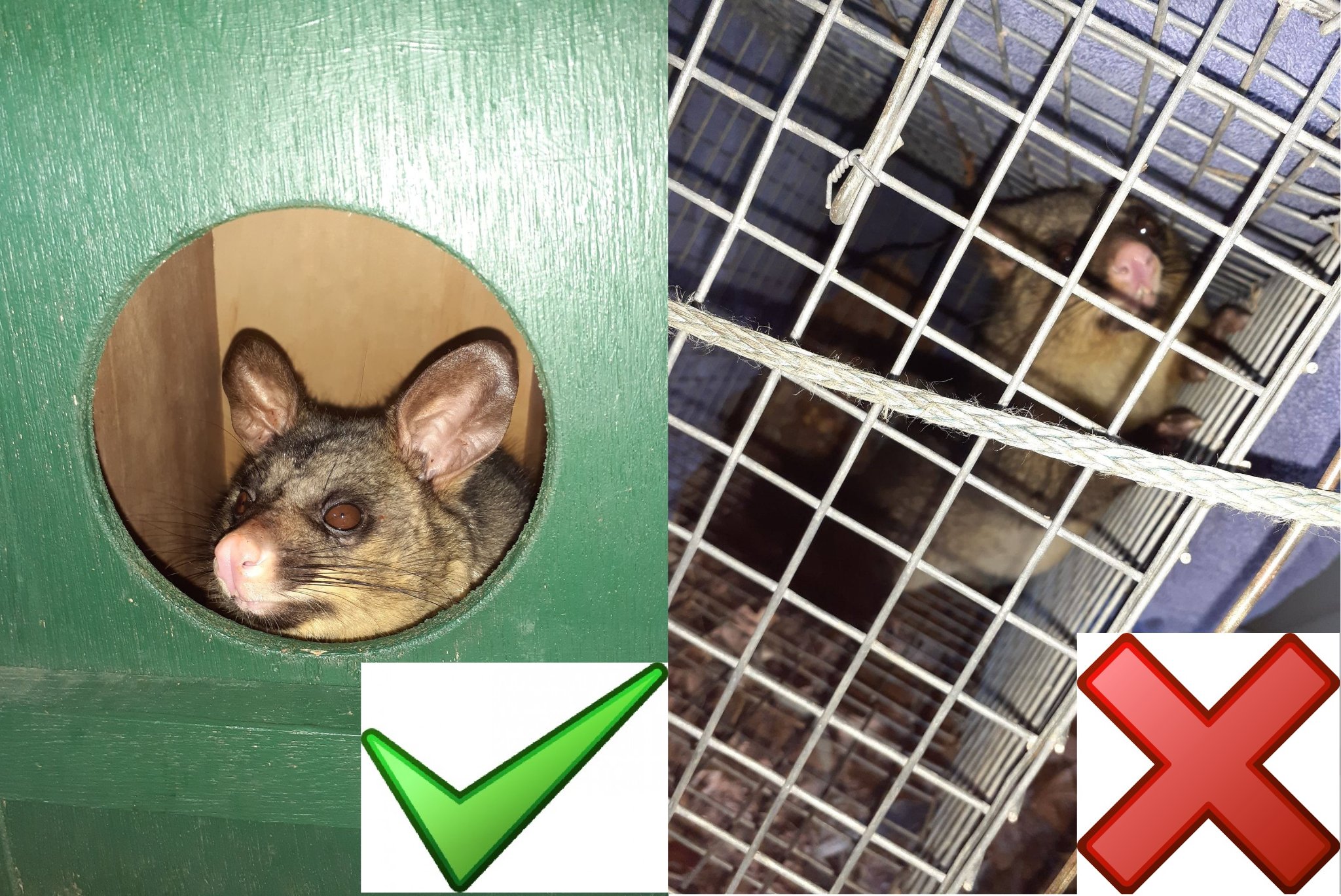

Sydney Wildlife rescues, rehabilitates and releases sick, injured and orphaned native wildlife. From penguins, to possums and parrots, native wildlife of all descriptions passes through the caring hands of Sydney Wildlife rescuers and carers on a daily basis. We provide a genuine 24 hour, 7 day per week emergency advice, rescue and care service.

Sydney Wildlife rescues, rehabilitates and releases sick, injured and orphaned native wildlife. From penguins, to possums and parrots, native wildlife of all descriptions passes through the caring hands of Sydney Wildlife rescuers and carers on a daily basis. We provide a genuine 24 hour, 7 day per week emergency advice, rescue and care service. Southern Cross Wildlife Care was launched over 6 years ago. It is the brainchild of Dr Howard Ralph, the founder and chief veterinarian. SCWC was established solely for the purpose of treating injured, sick and orphaned wildlife. No wild creature in need that passes through our doors is ever rejected.

Southern Cross Wildlife Care was launched over 6 years ago. It is the brainchild of Dr Howard Ralph, the founder and chief veterinarian. SCWC was established solely for the purpose of treating injured, sick and orphaned wildlife. No wild creature in need that passes through our doors is ever rejected.  Avalon Community Garden

Avalon Community Garden

Living Ocean was born in Whale Beach, on the Northern Beaches of Sydney, surrounded by water and set in an area of incredible beauty.

Living Ocean was born in Whale Beach, on the Northern Beaches of Sydney, surrounded by water and set in an area of incredible beauty.

Want to know where your food is coming from?

Want to know where your food is coming from?

Pittwater Environmental Foundation was established in 2006 to conserve and enhance the natural environment of the Pittwater local government area through the application of tax deductible donations, gifts and bequests. The Directors were appointed by Pittwater Council.

Pittwater Environmental Foundation was established in 2006 to conserve and enhance the natural environment of the Pittwater local government area through the application of tax deductible donations, gifts and bequests. The Directors were appointed by Pittwater Council.

"I bind myself today to the power of Heaven, the light of the sun, the brightness of the moon, the splendour of fire, the flashing of lightning, the swiftness of wind, the depth of the sea, the stability of the earth, the compactness of rocks." - from the Prayer of Saint Patrick

"I bind myself today to the power of Heaven, the light of the sun, the brightness of the moon, the splendour of fire, the flashing of lightning, the swiftness of wind, the depth of the sea, the stability of the earth, the compactness of rocks." - from the Prayer of Saint Patrick