June 2023 Report: Investigation Into The NSW Shark Meshing Program Finds Fairy Penguin Killed Not Recorded - Pregnant Shark Killed Not Recorded

Valerie Taylor AM, 88, and Bailey Mason, not yet 20, attended the Shark Nets Out Now protest at Manly on Saturday December 3rd, 2022

In May 2021 the Council called on the NSW government to remove shark nets on beaches in the Northern Beaches Council area and replace them with a combination of modern and effective alternative shark mitigation strategies that maintain or improve swimmer safety and reduce unwanted by-catch of non-target species.

Council made the call in response to Department of Primary Industries – Fisheries (DPI Fisheries) request for input from stakeholders on their preferred shark mitigation measures.

A number of residents addressed Council’s May meeting in support of shark net removal, including surfing champion Layne Beachley.

Then A/Mayor Candy Bingham said Council considered both the need to maintain or improve swimmer safety as well as the negative impacts on non-target marine species in reaching their decision.

“The effectiveness of shark nets has been questioned by many, yet their impact on other marine species is devastating,” Cr Bingham said.

“We have an aquatic reserve in Manly where turtles and rays are regularly seen by snorkelers, and up and down the beaches dolphins surf the waves alongside local board riders.

“The research conducted by DPI Fisheries found that 90% of marine species caught in nets were non-target species and that sharks can in fact swim over, under and around the nets anyhow.

“If the evidence is that there are other just as, or more, effective ways to mitigate shark risk, such as drone and helicopter surveillance, listening stations and deterrent devices, then we owe it to those non-target species to remove the nets.''

The shark mitigation strategy in New South Wales (NSW) has slowly been evolving over recent years. The introduction of Shark-Management-Alert-In-Real-Time (SMART) drumlines and shark surveillance drones has provided hope to those in the community who want to see the program cease its current lethal methods. But the State has been seemingly reluctant to make the final transition away from the lethal Shark Meshing Program (SMP) that still operates for eight months of the year.

A new report, 'Investigation into NSW Shark Meshing Program June 2023' by Envoy Foundation, covers the many shortcomings of the program in detail, including some that may not have been previously discussed. For example, trigger points should effectively alert the program's impact on threatened species, but instead, are reactive. Furthermore, when trigger points are tripped, there is no contingency plan for decisive and practical actions.

The Envoy Foundation report identified "extremely concerning discrepancies in data", including a photo of a bird found in shark nets in 2019 not included in data for the 2018/19 or 2019/20 catch data.

"There is an image of little penguin, also known as a fairy penguin — which are protected in NSW," Mr Borrell said.

"It's an image of a thing that was been pulled out of shark nets, but the animal does not appear in the data. How often does that happen?"

The report states the Envoy Foundation 'attempted to identify the bird but were not able to from the image or by speaking with the Protected Species and Communities Branch of the Biodiversity Conservation Division of the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment.'

The answer they received was:

“Unfortunately without the last digit (I can’t make it out either) it could be one of 10 birds. Each of the 10 birds were all banded in 2002 on one of three dates 22 OCT 2002, 29 Oct 2002 or 5 NOV 2002. The banding of these birds occurred at one of two locations:

Manly Point, Sydney Harbour; or Collins Beach, Spring Cove, Sydney Harbour. That is about as much as I can provide without the last digit to actually individually identify the specific bird.''

''Additionally, images obtained show pregnant female sharks caught and killed that have been cut open, exposing a uterus full of pups. These pups are not included in the reported count of sharks killed, and any assessment made is done based on understated data.'' the report states

The images had to be obtained under GIPA applications.

''We were originally blocked access to detailed Shark Meshing Program (SMP) catch data via Government Information (Public Access) Act 2009 (NSW) (GIPA Act) under application GIPA20-1157, with the supplied reasoning stating that catch information is made available in the Annual Performance Reports, as follows:

“GIPA 20-1157 - Information publicly available. The requested statistical information in scope can be located on the Departments website https://www.sharksmart.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/856165/Report-into-the-NSW-SharkMeshing-Program.pdf for data between 1950 to 2009.

Additionally, https://www.sharksmart.nsw.gov.au/shark-nets contains locations, species, and fate data from 2013 onward.”

The data provided in these Annual Performance Reports are not detailed enough to make any type of meaningful independent scientific inquiries or conduct any detailed critical analysis of the SMP.

As such, we reapplied for this data again and were eventually granted access (GIPA 22-64). Whilst eventually granted, the initial rejection shows an inclination to avoid independent inquiry into the program and must be considered actively hostile to analysis, and designed to dissuade third parties from accessing important data. It should not require two GIPA applications to access such basic information that is clearly in the public interest.

After eventually gaining access to this information, we noted many cases of data inaccuracy.'' the authors state.

Mr Borrell said the report also questions assumptions by the Department of Primary Industries that animals released alive would survive.

"If an animal is cut out of a shark net and goes down in the water that goes down in the data as alive," Mr Borrell said.

He said footage obtained through freedom of information showed some of the sharks in "pretty unhealthy states".

"They sort of go belly up and sink down towards sea floor," he said.

The report found that Post-release mortality rates of animals are not made available, many of which would likely succumb to stress and injury post-release, based on the visual evidence obtained.

Although the dataset only starts in 1950, anecdotal evidence tells us that the first decade of the program was high on catch.

For the purposes of accuracy (more animals identified down to species level) and currency, only data for the last 22 years from 1999-2021 is discussed in the report.

Sphyrnadae, or hammerhead sharks, are the most represented genus in the NSW shark catch data. The 1,132 individuals caught make up 37.6% of the total catch. Of the 1,132 hammerhead sharks caught, 98.9% (1,119) were found dead due to several factors that make hammerheads more susceptible to succumbing to stress.

''Identification to the species level was mandatory only after 2014, however, we are unable to evaluate how accurately contractors are able to identify to the species level.'' the report notes

''The high numbers of all hammerhead species caught are more concerning as S. lewini and S. mokarran are now both listed as critically endangered in most Australian states. Size data indicates the removal of many juvenile sharks, which will negatively influence the prolonged population of the species.

Ultimately, the extremely high number of non-target species caught, including these hammerheads, negates any perceived metric of success from this program.''

Further, we note an almost complete absence of non-shark catch being listed in the catch data from 1950-1990. This means that historical catch data and population impacts of the program are understated, and data can once again not be relied upon.

This creates scientific uncertainty, and by applying the precautionary principle, this program is recommended to cease on this basis.

Other sharks of concern

The bulk of the remaining sharks caught are a mix of genera and species including two target species, the great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) and the tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier).

Again, an average size of 1.9m and 2.94m for great white sharks and tiger sharks respectively indicate that even though these are target species, juveniles are the most commonly caught. Juveniles pose little threat to swimmers. Whether this is representative of the overall population or an effect of the catch method used requires further research to arrive at any conclusion.

The final species of concern is the critically endangered grey nurse shark (Carcharias taurus). Of the 146 caught, 70 were killed. These sharks have a high tourism value, meaning this is not only an ecological problem but an economic one.

According to a report published in April 2022, a recent study found that Australia wiped out a genetically distinct population of southeast Australian tiger sharks before it was even known they existed. In an interview with Yahoo News, one of the authors of the report, Dr. Alice Manuzzi from the Technical University of Denmark, said the decline appears to coincide with two factors, one of them being the introduction of shark control programs.

The rudimentary and inaccurate data gathered in the SMP makes it difficult to ascertain the program’s adverse effects fully, including its impact on the now extinct south-eastern tiger shark population.

Excluding the shark species already mentioned, numerous endangered species are consistently caught and killed in shark nets.

Marine turtles are commonly caught, and of the six species found in Australian waters, five have been caught in this program. The species C. mydas and Eretmochelys imbricata are endangered andcritically endangered respectively while other species of sea turtles are vulnerable, all with decreasing population trends.

Additionally, several species of rays are caught in nets with giant manta rays (Manta birostris) of particular concern due to their conservation status of endangered and their high economic value from tourism.

Animals of public/tourism interest

While some animals may not be of conservation concern, they still hold significant public interest due to their charismatic nature, making them a drawcard for tourism. Rays, aside from manta rays, constitute a huge portion of the catch, with a total of 2,172 captured, and 642 (29.6%) of those were dead. Rays are of minimal risk to swimmers and are highly desired sightings by divers.

The most prominent groups caught are the Myliobatiformes (eagle rays, including Myliobatis australis) and Rhinoptera neglecta. Both of these groups exhibit schooling behaviour, which is indicated in the catch data when many are caught in close succession.

Marine mammals are also caught in these nets including whales, dolphins, and pinnipeds (seals and sea lions). Even though numbers are low compared to other taxa found in the nets, the high mortality rates and public affinity towards these animals are cause for concern.

The highest mortality rate is the common dolphin with 45 killed by the nets along with 22 common bottlenose dolphins and 9 Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins. Of those captured, 100% were found dead, along with 15 animals only classified as Delphinidae.

As with other data, broad classifications disappear completely, in this case around 2013, and animals are classified down to species after this point. This makes it difficult to determine the numbers of each species up until this point which were previously amalgamated into broader classifications.

Humpback whales are also present in the data which excludes several known entanglements following April 2021. Of the six entangled whales, two were dead. It is important to note that the condition of animals being released are rarely recorded, and the numbers released alive is not an indication of their post-release chances of survival. It is thought that many will succumb due to injuries, stress, vulnerability, or other factors associated with entanglement in the nets.

In October 2021 a juvenile humpback whale was caught in a shark net at Whale Beach and was spotted around 2.30 in the afternoon, struggling.

The entanglement came only hours after a pregnant bronze whaler shark was freed off Mona Vale beach.

The SMP is allowed to operate due to a Joint Management Agreement (JMA) between the Department of Primary Industries (DPI) and the Environment and Heritage Group (EHG) within the Department of Environment and Heritage. The agreement outlines the roles and responsibilities of the agencies involved in the meshing program and is reviewed every five years to ensure it meets its objectives.

''The 2017-2022 five-year JMA was due for review at the end of 2022. A Senior Policy Adviser to the Minister for the Environment confirmed in July 2022, that the JMA would not be rolled over and assured us that the JMA would be updated and public consultation would occur before finalisation.'' the authors state in the report

''In early 2023, just prior to this report being finalised, DPI advised that following the completion of the internal review, the JMA has been rolled over without amendment and without public consultation, despite the JMA not meeting its objectives. We were advised that:

“From the Department level I can tell you that a preliminary meeting was held with DPI, EHG, the Fisheries Scientific Committee (FSC) and the Threatened Species Scientific Committee (TSSC) prior to the JMA being reviewed. Numerous aspects of the JMA and Management Plan were discussed with the trigger point system being a key focus point. The JMA has been subsequently reviewed by DPI and EHG (as Parties to the Agreement) with the major outcome being that the JMA not to be amended, and trigger points need to be reviewed as part of the Management Plan.

The Management Plan controls the operational aspects of the SMP, and it is this document that DPI and EHG are in the middle of adjusting with the trigger point review system being a huge focus. DPI and EHG have been investigating alternative catch monitoring systems with the aid of internal and external biometricians. The current trigger point system will remain in place until a better system has been reviewed and endorsed by the FSC and TSSC and subsequently signed off by DPI and EHG, with other minor changes being made at the same time.

In accordance with the Fisheries Management Act, as the JMA document is not being amended/redrafted then there is no public consultation required. The Management Plan (as mentioned) is the operational document and can be amended at any time once all Parties agree and it is endorsed by the FSC and TSSC. If you have suggestions/ideas for potential changes to the Management Plan, then perhaps provide those to the FSC and/or TSSC”

The report also found the the SMP breached the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) on numerous and ongoing occasions:

''Based on the data analysed, we have identified an intensification of catch over the last two decades for many Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) listed species, which is in breach of the EPBC Act.

The NSW Government’s position on its requirement to adhere to the EPBC Act when it comes to shark nets is:

'9.5 An action that has, will have or is likely to have a significant impact on matters of national environmental significance may need approval under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. Section 43B of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 provides that actions that are a lawful continuation of use of the land, sea or seabed that was occurring before 16 July 2000 are not subject to approval under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999.

9.6 Approval under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 for the SMP was not sought in 2009 (when the first Management Plan was enacted) on the basis that the SMP was a lawful continuation of use of the land, sea or seabed and was therefore covered by the continuing use exemption in section 43B of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999.'

Below is an excerpt from Section 43b, which is the basis that the SMP currently operates. Bold has been added by us to highlight areas of concern.

43B Actions which are lawful continuations of use of land etc.

(1) A person may take an action described in a provision of Part 3 without an approval under Part 9 for the purposes of the provision if the action is a lawful continuation of a use of land, sea or seabed that was occurring immediately before the commencement of this Act.

(2) However, subsection (1) does not apply to an action if:

(a) before the commencement of this Act, the action was authorised by a specific environmental authorisation;

and

(b) at the time the action is taken, the specific environmental authorisation continues to be in force.

Note: In that case, section 43A applies instead.

(3) For the purposes of this section, neither of the following is a continuation of a use of land, sea or seabed:

(a) an enlargement, expansion or intensification of use;

(b) either:

(i) any change in the location of where the use of the land, sea or seabed is occurring; or

(ii) any change in the nature of the activities comprising the use; that results in a substantial increase in the impact of the use on the land, sea or seabed.

From the data, we believe that since 2000 and the introduction of the EPBC Act there appears to be an intensification of catch in the following species:

- White Shark (513 caught in the 50 years pre-2000, 267 caught from 2000 to 2021)

- Green Turtle (0 caught in the 50 years pre-2000, 72 caught from 2000 to 2021)

- Leatherback Turtle (0 caught in the 50 years pre2000, 13 caught from 2000 to 2021)

- Common Dolphin (4 caught in the 50 years pre2000, 41 caught from 2000 to 2021)

- Bottlenose Dolphin (1 caught in the 50 years pre2000, 21 caught from 2000 to 2021)

- Silky Shark (0 caught in the 50 years pre-2000, 18 caught from 2000 to 2021)

- Scalloped Hammerhead (8 caught in the 50 years pre-2000, 22 caught from 2000 to 2021)

''Catch data shows a clear intensification of catch since 2000, making operating under the 43b exemption illegal. This is a serious and ongoing breach of 43b that requires the SMP to seek federal environmental approvals.'' the report states

These approvals should have been sought prior to intensification, or the program should have been ceased or scaled back to reduce catches to pre-2000 levels. At this point, after many years of operating in breach of the federal EPBC Act, the only tenable option is for the program to cease entirely. The program can no longer legally operate within federal law.

It is worth nothing that the data shows an increased negative impact on protected species during the terms of the last two JMA’s - a gross beach of these agreements.

This requires termination of the current JMA for not meeting its objectives, meaning the program can no longer legally operate within NSW law.

Recommendation 2 is that:

The Federal Minister for the Environment call in a review of the SMP for suspected breaches of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Act 1999 and to investigate the impact of the SMP on threatened and protected species, particularly migratory species.

Another critical issue is the need for more data quality and transparency, including that there is no data available on the program's impact on the environment more broadly. Missing and inconsistent reporting by shark meshing contractors, both historic and ongoing, leads to data inaccuracy. Data accuracy and integrity are vital for the accurate assessment of this program. In addition, mortality rates of animals initially released alive are not made available post-release, many of which would likely succumb to stress and injury post-release based on visual evidence obtained.

The report also highlights that although the SMP is a NSW program, shark tracking data shows impacts go beyond the State's jurisdiction, this also applies to the Queensland (QLD) Shark Control Program, particularly for migratory species such as Tiger Sharks, White Sharks, Grey Nurse Sharks and other non-target species.

In addition, a growing number of surveys show public opinion opposes shark meshing for various reasons, including but not solely due to its ineffectiveness, the killing of marine animals, its impact on the marine environment, and disturbance to marine ecosystems. NSW Local Governments also oppose the SMP. Sadly, the NSW government's actions fail to align with the growing community opposition to shark nets, including not publicly releasing the results of recent community shark sentiment surveys.

''Overall, the investigation finds that the SMP is not achieving its goal of keeping ocean goers safe from negative shark interactions. It is also clear that it has a disastrous and potentially long-lasting effect on the marine ecosystem. The overarching recommendation of the investigation is that the NSW government immediately prioritise the withdrawal of shark meshing and develop a well-structured short-term phase-out strategy should shark nets return to the waters for any further meshing seasons beyond 2022/23. Simultaneously, the NSW government's efforts must be directed towards further implementing alternative, non-lethal shark mitigation methods that protect both humans and marine ecosystems.'' the authors state

This investigation covers all the above points in more detail and explores other significant issues and shortcomings of the current SMP. The investigation makes 12 recommendations for the urgent consideration of the NSW government and the Federal Environment Minister.

The findings of the investigation are available here.

NB: the images of deceased animals, including the fairy penguin and pregnant shark, are available in the report.

Previously

- Large Leatherback Turtle Found On Whale Beach: Deceased - March 2023

- Northern Beaches Shark Net Death Trap Continues: Community Calls For Shark Nets Out Now - December 2022

- Manly's Little Penguins: Warden Program Update - October 2022 - calling on community to send in reports of Fairy penguins as they have disappeared from Manly

- Shark Meshing (Bather Protection) Program 2021/22 Annual Performance Report - Data Shows Vulnerable, Endangered and Critically Endangered Species Being Found Dead In Nets Off Our Beaches - August 2022

- Shark Listening Stations + Drumlines Have Been Installed Off Our Beaches - May 2022 Update

- Pittwater's Turtles Impacted By Boat Strikes In The Pittwater Estuary: 4 Knots Speed Limit/Distance To Shore Being Ignored - April 2022

- Juvenile Humpback Whale Caught in Shark Net off Whale Beach Renews Community Calls for Shark Nets to Not be installed until the Southern Migration ends - October 2021

- New Fleet Of Shark-Spotting Drones For New South Wales - July 2020

- NSW Shark Meshing (Bather Protection) Program 2020/21 Annual Performance Report: 90% Of Northern Beaches Marine Animals Entangled Were Not Targeted Sharks, Included are Threatened or Protected Species Mortalities

- Shark Nets Are Destructive and Don’t Keep You Safe – Let’s Invest In Lifeguards - December 2019

- Shark Drumlines Going In Off Our Beaches - September 2019

- NSW DPI's Shark Meshing 2019/20 Performance Report Released

- DPI Shark Meshing 2018/19 Performance Report: Local Nets Catch Turtles, a Few Sharks + Alternatives Being Tested + Historical Insights

- Lion Island's Little Penguins (Fairy Penguins) Get Fireproof Homes - June 2019

- Pittwater's Little Penguin Colony: The Saving Of The Fairies Of Lion Island Commenced 65 Years Ago This Year - April 2019

- Noah's Ark (Shark) Incidents in Pittwater - History insights

- Pittwater Fishermen: Barranjoey Days - History page

Local Shark Net Toll

About The Envoy Foundation

"We empower Conservationists, Scientists, Filmmakers, Entrepreneurs, and businesses to scale their positive impact on the world." - Andre Borell, Founder

Envoy Foundation is an environmental-focussed organisation that aims to scale-up the impact of work being done by conservationists, scientists, filmmakers, entrepreneurs, and businesses who are working towards a world free of animal and ecosystem exploitation, aligning with our mission, vision, and values.

We provide support services to experts in their field, who might not have the time or ability for social media, marketing, fund-raising, grant-writing.

We finance and produce impact filmmakers' documentaries that are unbackable by traditional standards.

We invest in for-purpose businesses that might not be able to get traditional capital injections.

We support investigative reporting on environmental issues that mainstream news outlets don't have the resources or autonomy to undertake.

We use our resources to make the world a better place. We are funded through generous donations by our community, by corporate and philanthropic giving, and by any future profits that our projects or investments generate.

We do this work in alignment with the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals, however, we commit to substantially exceeding Life below Water (#14) and Life on Land (#15) commitments. It is our position that these do not go far enough to explicitly protect ecosystems and animals.

The Envoy Foundation will.

''Yesterday afternoon we spent frustrating hours watching a young whale stuck in the 'shark' net at Whale Beach. Struggling to breathe.

As you may know, or not...these nets are designed as a placebo for our hyped up fear of sharks, and they do zero to manage that species and in fact destroy a wide spectrum of other species.

Sydney local councils, Living Ocean, ORRCA, Humane Society International Australia, the Australian Marine Conservation Society and more have all called for the concept to be scrapped in favour of other 'smarter' ways to protect ocean swimming humans. The irony here is we are actually the problem.

We KNOW that on the southern migration, mother and calf Humpbacks swim south close to the coast late spring. Lots of reasons for them to do this. We also know the time frame for when they do this. So to place whale traps directly in their path is some sort of insanity.

At current global pricing this young whale yesterday, is worth very close to US$ 5.4 million in terms of carbon capture. Our Humpbacks sequester carbon and help modify our overheating climate like nothing else except trees and we have taken 50% of the trees from Australia since Europeans arrived here and set up.''

Robbi Luscombe-Newman

Living Ocean

Co founder, President.

October 2021

Did you know that we once had Little Penguins right along coast - that they would come ashore on every beach to make nests and raise young? Yes - we did. You may even see some offshore when surfing - they're still around, although increasingly at risk from predators such as introduced foxes or those who take their dogs offleash into their homes. This si the prime reason we need Penguin Wardens.

A few insights from just a few years ago.

In June 2019 we brought you some news about a project to put fireproof burrows on Lion Island for the colony that lives there - these penguins are seen in the Pittwater estuary and right along the coastal beaches. They used to have nests and colonies on the beaches all along our coast as well - at Turimetta Beach, Narrabeen and Long Reef in particular.

Here's some at Narrabeen in 1955 - and reports of them at Long Reef as well:

When summer comes . . .

.jpg?timestamp=1619878281381)

HE MUST go down to the sea again, the lonely sea and the sky- but only for dinner. This hungry little chap couldn't wait for the rest of the flock that gathers for a nightly 3 a.m. party on the beach. Then they return to their nests to sleep all day.

.jpg?timestamp=1619878349216)

HOUSING TROUBLES begin, at Mrs. E. Whittaker warns off a mother bird for squatting with its young beside her shed. But (inset) the penguin family sits tight till ready to vacate.

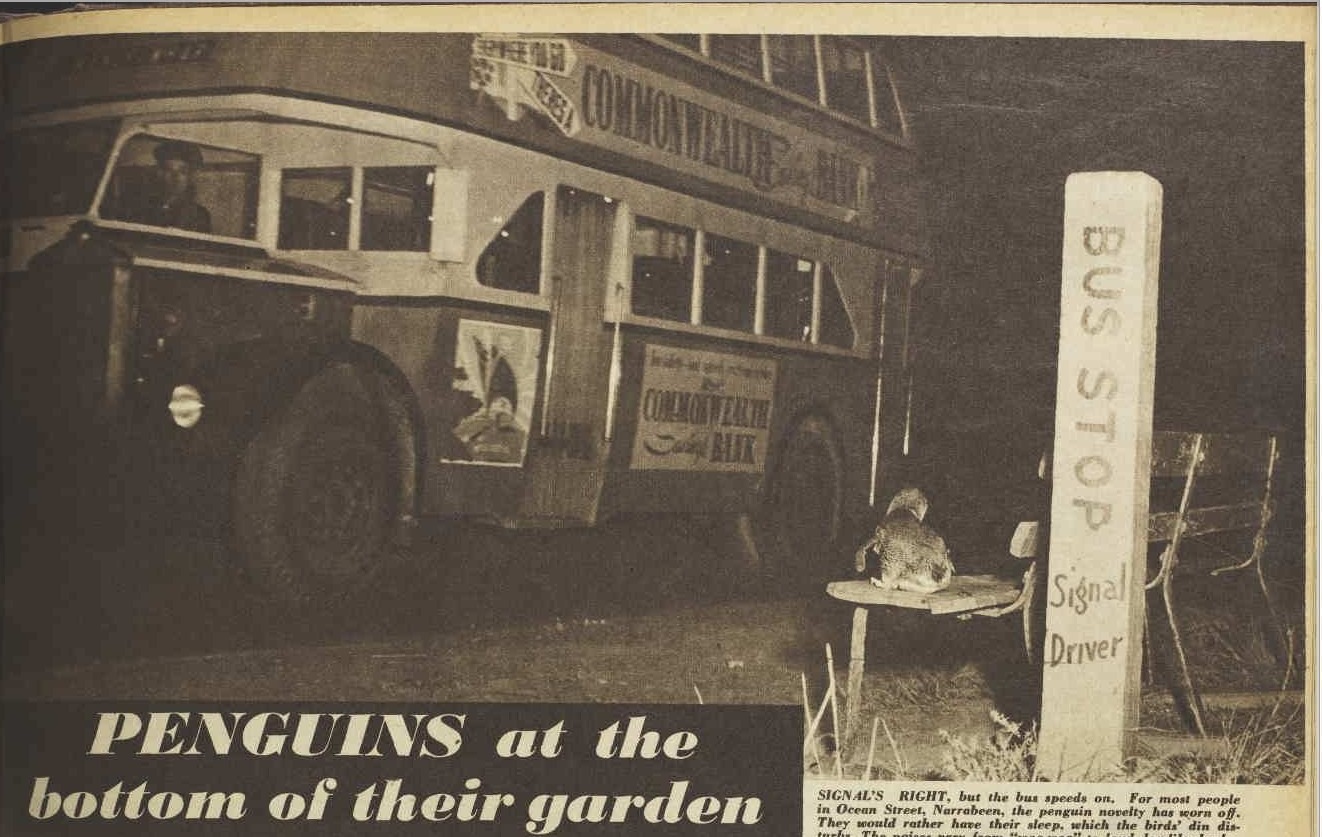

PENGUINS at the bottom of their garden

Spring comes with a difference to the gardens of waterfront homes in Ocean Street, Narrabeen, north of Sydney. It brings flocks of fairy penguins-the smallest of the breed-sauntering in from the sea to take up residence for their nesting season. As daytime guests they're welcome, but at nightfall they head down to the sea for food-making noises that keen everyone else awake, too. They stay for a few months.

HUNTING for invaders under the house, this family is helped by neighbors. Householders have M tried fencing and boarding around their houses, but still the penguins come to nest each year.

SIGNAL'S RIGHT, but the bus speeds on. For most people in Ocean Street, Narrabeen, the penguin novelty has worn off. They would rather have their sleep, which the birds' din disturbs. The noises vary from "woo-woo" to loud dog-like barks.

.jpg?timestamp=1619878478650)

THE MAN who came to dinner takes it for granted he's welcome as Mr. W. Gillanty greets him. Residents, particularly light sleepers, now have to resign themselves to a trying time while the penguins, which are protected, are in charge. PENGUINS at the bottom of their garden (1956, December 12). The Australian Women's Weekly (1933 - 1982), p. 23. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article41852332

Marine Parade North Avalon resident and ornithologist Neville Cayley is mentioned in this one:

Two Little Penguins

AS Mr. Neville Cayley mentions in the 'Mail' that there is very little known regarding the length of time these penguins care for their young before turning them out, I thought the following account would be of especial interest to readers of 'Outdoor Australia.'

At a crowded Museum lecture Mr. Kinghorn told us this unusual incident. One morning towards the end of August, 1921, the peace and serenity of some dwellers at Collaroy Beach were disturbed by extraordinary noises and weird cries at the back door. When the astonished owner of the house opened the door in rushed two little penguins, which with loud voices announced their intentions of staying. Then they danced about and waved their little wings in a most ingratiating way. After a short time these noisy visitors were shown the door, and they disappeared for a while. But, having chosen their home, Mr. and Mrs. Penguin returned later, and as they could not get inside the house they went underneath as far as they could get, and there made their nest of seaweed. The noise every night was almost unbearable; they would scream and cackle, and later, after about six weeks their songs of joy were terrific, for two youngsters were hatched.

About four months after their arrival the penguin family suddenly departed. Where they wintered is their own secret: but late in the following August a terrible cackling outside advised these householders that they were back. When the door was opened Mr. and Mrs. Penguin marched triumphantly in, followed by two grown chicks, which were inquisitive and rather shy. Then followed extravagant dances of greeting and vociferous songs of 'Here we are again,' etc., in which the young ones also joined.

They could not be quietened, and the neighbours hastened across to see if someone had gone mad. The owners of the house put the whole family down on the beach and drove them away. It was then that the parents sent off the chicks to fend for themselves, and they themselves returned later and went under the house to their old nest. The celebrations were so overpowering that the householders took down some boards next day, got the noisy pair out, and drove them at night by car to Palm Beach, about twelve miles distant, and there left them. But next morning saw them back.

They were taken a second time, but returned, and were allowed lo stay; but a home was made for them in the far corner of the garden. The house side was netted off and a hole cut in the fence to allow them free access to the beach. They made a nest of seaweed, and later two eggs were laid. The birds look it in turn to sit on them, and there was always much shouting and scolding when one returned from the sea at night.

After about six weeks two sooty-brown chicks appeared, and the noise that night and the next few days while the celebrations lasted was tremendous. The parents took it in turn to fish and swim during the day that followed, but at night they often went out together to find a suitable supper, and about 9 p.m. would return, arguing together as they came up the beach. The following summer my father saw a young penguin land on the rocks at Coogee. I think it quite likely that it was one of the young ones turned out at Collaroy. It was evidently not very used to fending for itself, for a patch of feathers was torn from its shoulder, possibly through not being an adept at landing.

At the time of the lecture these queer visitors were still in residence at Collaroy, and what became of them I do not know. It is likely enough that the nesting-place on North Head mentioned by Mr. Cayley is occupied by these little penguins or their descendants. Outdoor Australia (1925, March 18).Sydney Mail (NSW : 1912 - 1938), , p. 10. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article159721727

It is recorded that two Fairy penguins for a number of years made seasonal visitations to Collaroy, near Sydney, and often laid their eggs under the floor of one of the houses there. — F.J.B. Quaint and Beautiful Sea Birds (1934, October 31). Sydney Mail (NSW : 1912 - 1938), , p. 56. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article166107257

The Lion Island colony was officially first protected 65 years ago - although they had been protected decades prior to then:

PROTECTION OF PENGUINS.

Mr. Oakes (Chief Secretary), who is in charge of the Act relating to wild life, desires it to be generally known that all species of penguins are absolutely protected by law, and that anyone interfering with the birds is liable to a penalty. Apart from this he says citizens are requested to refrain from molesting this interesting bird, or driving it back to the sea, as, naturally, no water fowl liked getting wet when half-feathered.

Mr. Oakes remarked yesterday that fairy penguins, which were frequently seen off the coast, came ashore at this period of the year for moulting purposes for about three weeks. During that time they had not been observed to feed or enter the water. Many persons had offered specimens of the birds as exhibits to the Taronga Zoological Gardens, while others had made inquiries how to keep them alive in captivity. As this species of penguin only lived on live fish they could not be kept alive away from the sea. PROTECTION OF PENGUINS. (1923, December 18). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 8. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article16127509

PENGUINS ON COAST ARE PROTECTED

A penguin caught to-day near Palm Beach v/as refused' by Zoo authorities. The birds are common along the coast at present, are protected by law, and do not live in captivity.

The secretary of the Zoo (Mr. H. B. Brown) said today that the public had been warned against molesting the birds. PENGUINS ON COAST ARE PROTECTED (1936, December 30). The Sun (Sydney, NSW : 1910 - 1954), p. 12 (COUNTRY EDITION). Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article230907746

Surfers and people on boats report seeing them on an almost daily basis in our area. There is also a Fairy Penguin Colony at Manly.

The ladies from the Fix It Sisters community group have extended their project beyond Lion Island to the South Coast of NSW. In March 2021 they reported that:

Success at Snapper Island!

(This is part of the Eurobodalla Shire Council - which is on the South Coast of NSW)

Update on our Penguin Burrow project. Since installation of the first burrows at Snapper Island (Batemans Bay), some of the penguins have taken up residence and in 2020, gave birth to chicks. Exciting development for our burrow project.

In the meantime, FiS has been working hard in partnership with Pink Cactus on improving the design of the original burrows.

Fix It Sisters photo, March 16, 2021

Fix It Sisters photos, March 16, 2021