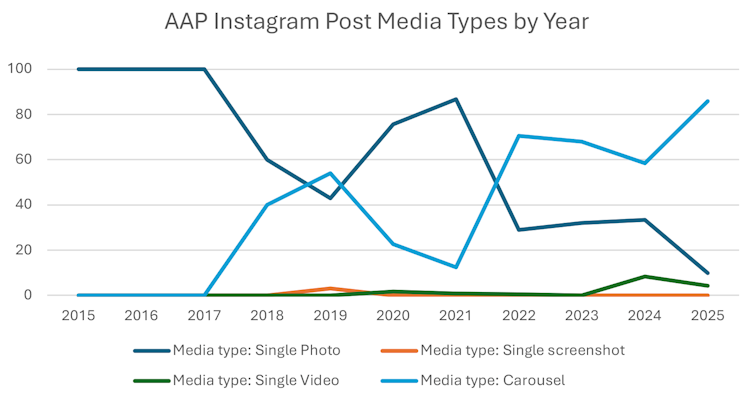

Bayview + Mona Vale + Brookvale Bricks: Makers Mark Every run of 10 Thousand

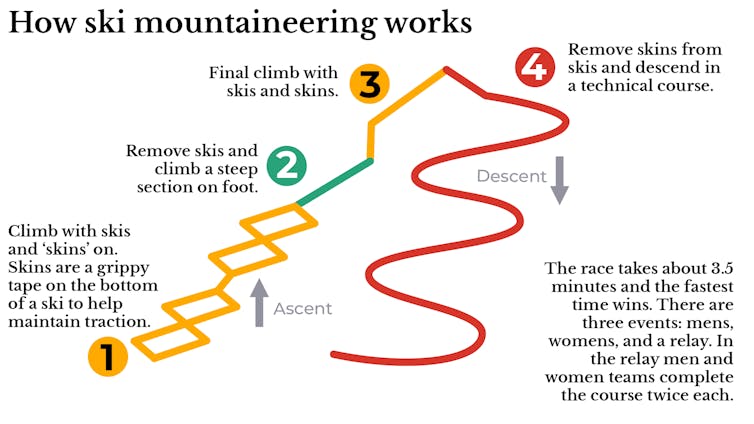

These two bricks were gifted to us decades ago by Charles Benko. Charles stated he got these ones from Brookvale Bricks, when they were still around.

He explained the markings on these bricks, which are marked with a pipe in one case, and two thumbprints to make a heart or harp in the other, is made when the maker had completed run of 10 thousand of them. They would place a personal insignia in that 10 thousandth one made to mark the end of a run.

%20smaller.jpg?timestamp=1770841935247)

%20smaller.jpg?timestamp=1770841973640)

Charles who lived at the back of Manly near Condamine street, and was a Hungarian who spoke of Auschwitz – his wife was French (Suzanne ?), came to Australia after World War Two. He passed away aged 99 years back now, but his gift of old Brookvale bricks, and stories of our area in the late 1940's and early 1950's, prompted a look into brick making in our area.

Bricks have been a part of what was needed in Sydney since the first colonists landed here, hoping for a better life than that left behind.

This is a sketch of 'Brickfield Hill' in Sydney - near today's Surry Hills (and Hyde Park). The sketch is dated 1796 - and is among the great records held by the State Library of NSW, many of which have been digitised and area available online.

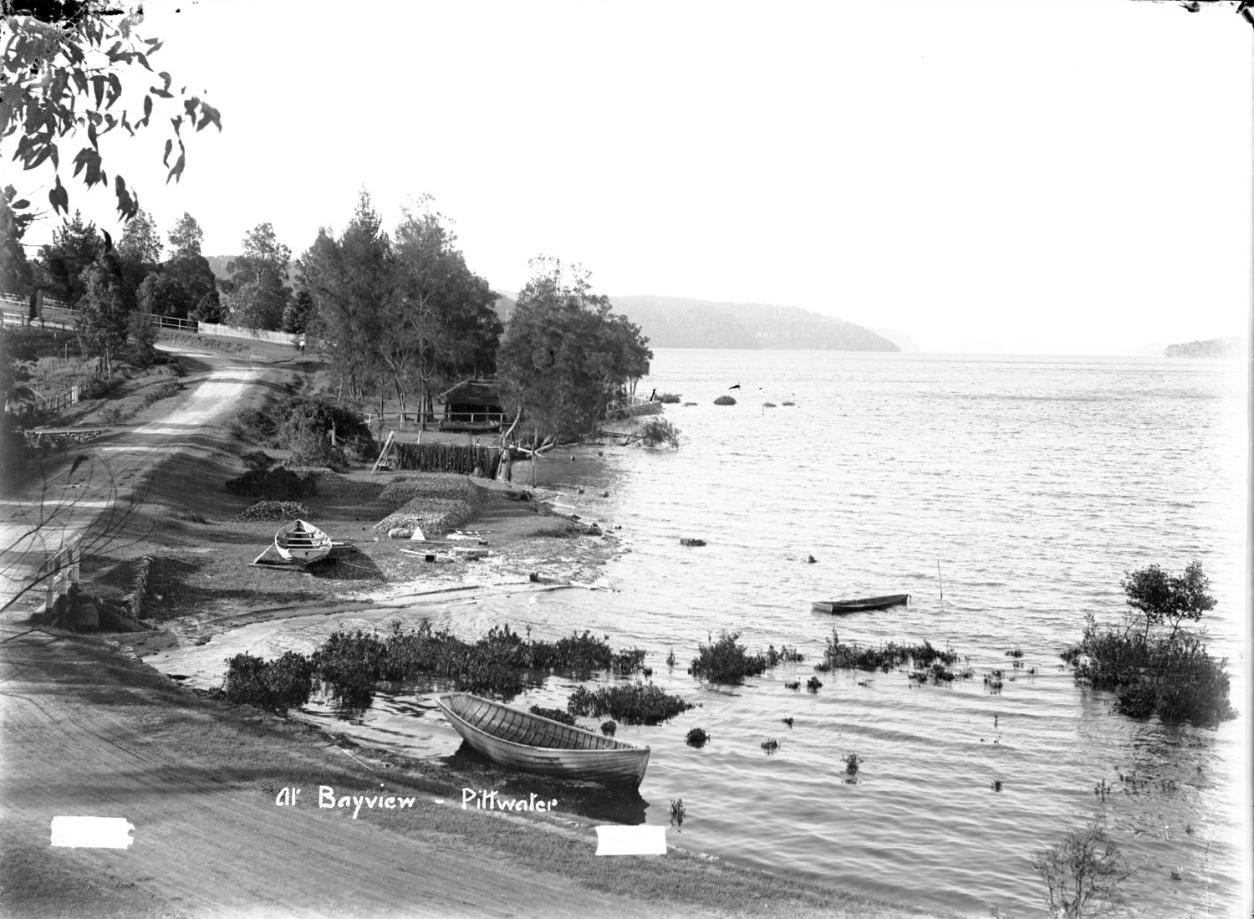

Bayview- Mona Vale Brickworks

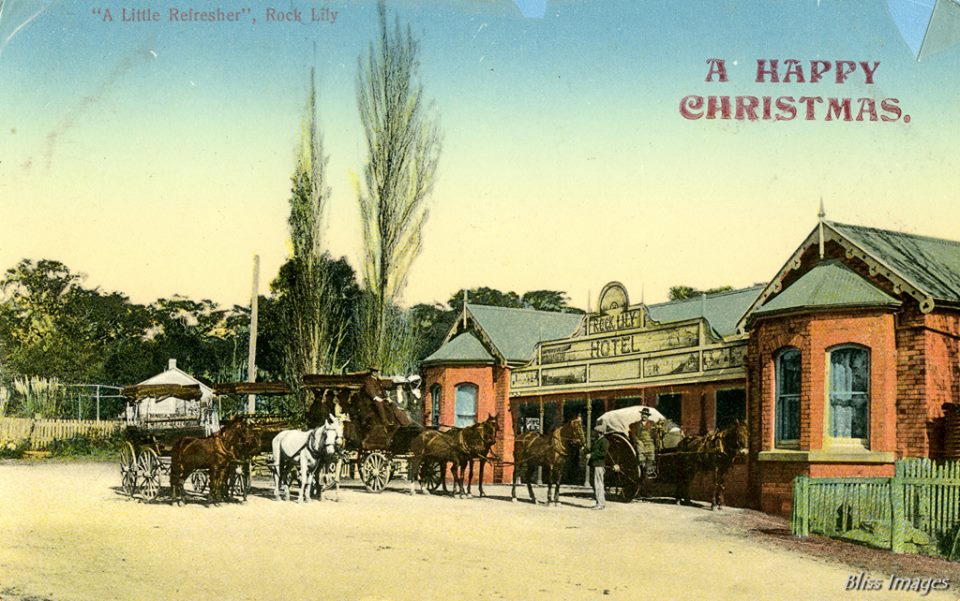

The bricks that were used in the Rock Lily at Mona Vale are said to have come from a brickworks at the Bayview-Church Point end of Pittwater road by the Austin family:

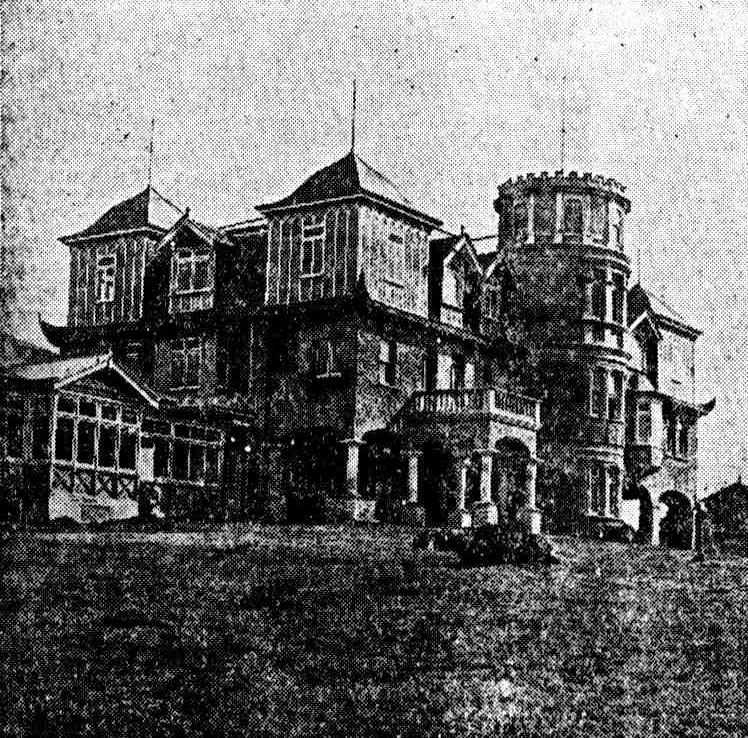

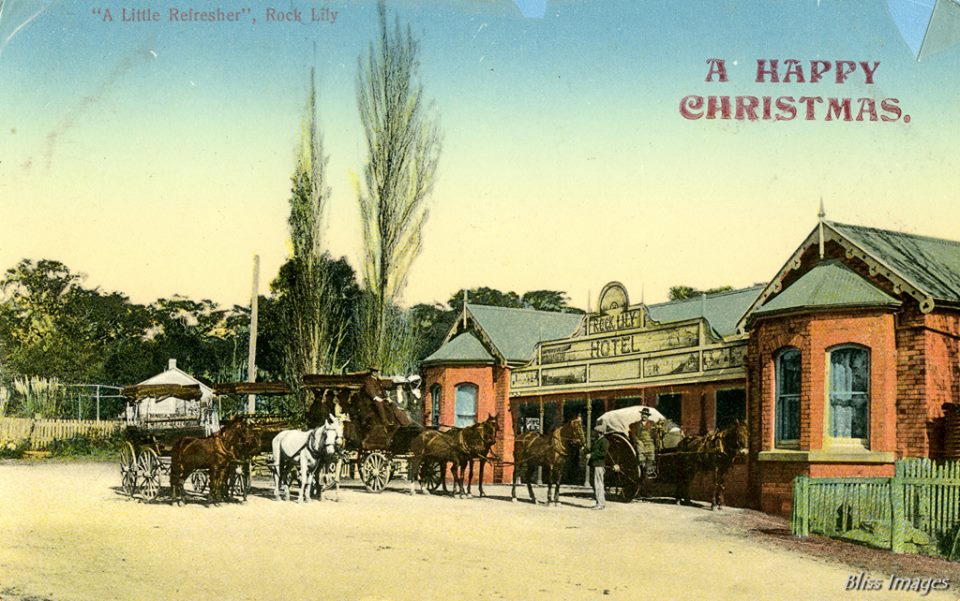

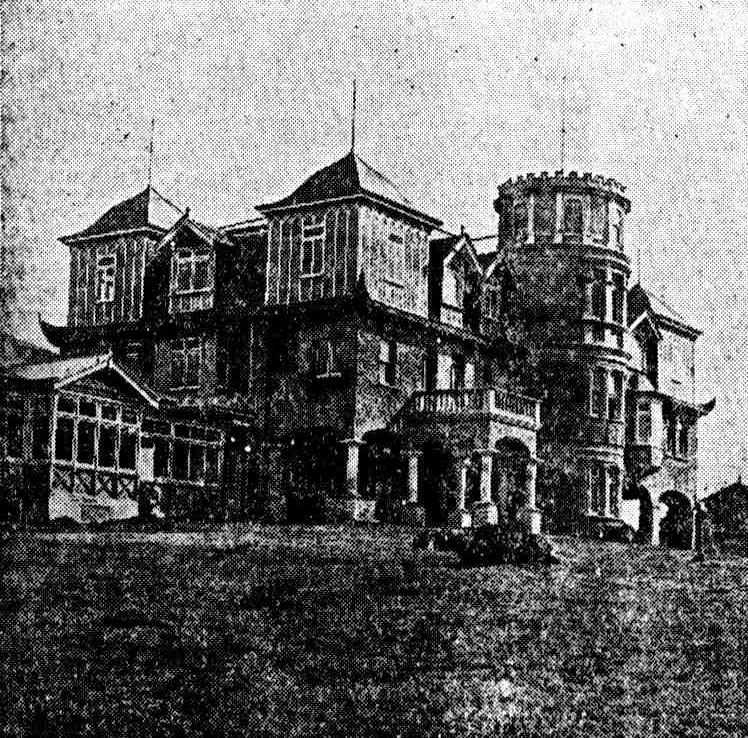

Rock Lily circa 1895 - 1900 - Christmas postcard.

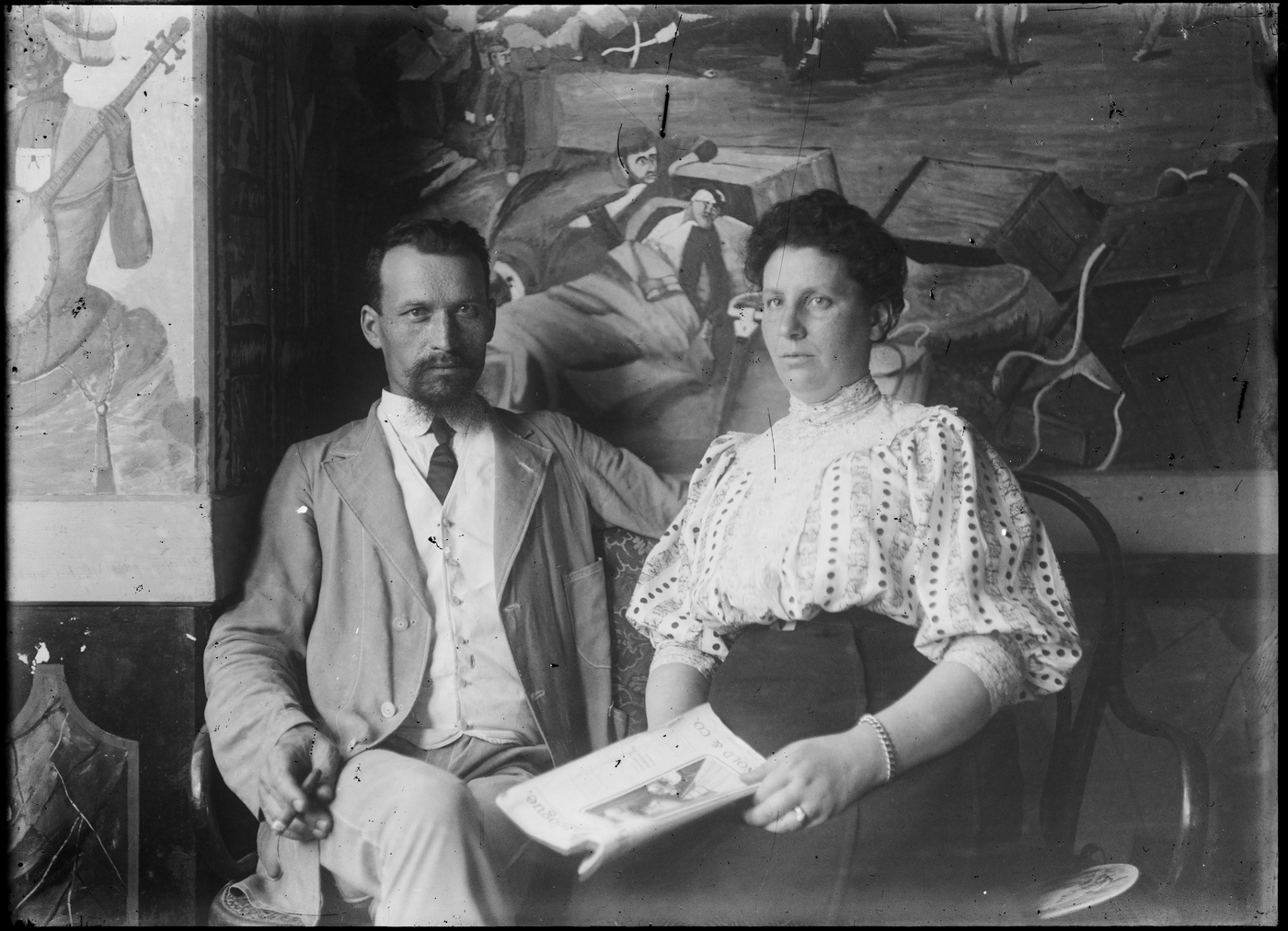

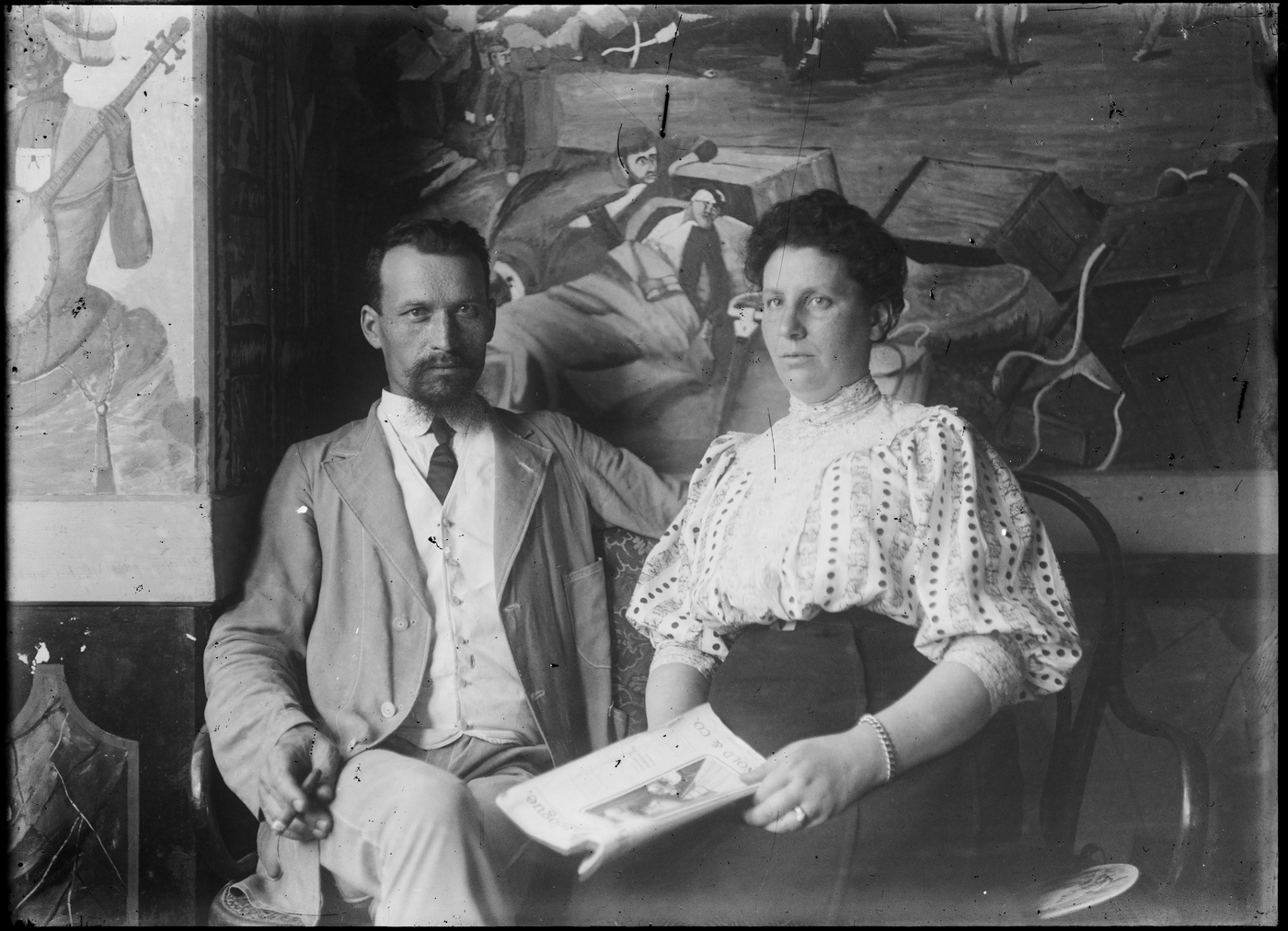

Rock Lily Hotel [Narrabeen] from State Library of NSW Album: Portraits of Norman and Lionel Lindsay, family and friends, ca. 1900-1912 / photographed chiefly by Lionel Lindsay. Image No.: a2005211h - Auguste and Justine Leontine Briquet are on front entranceway

NB: when it was being demolished/renovated in 1988:

This photo taken on October 9th, 1988 of the renovation of the structure shows the original creamy bricks that were made at the Bayview brickworks of of J W Austin. Photo and information courtesy Avalon Beach Historical Society president Geoff Searl OAM.

An anecdote recorded by a resident of then, Mr Wheeler, tells us the location:

Continuing our old-time journey, the coach climbs a hill, and on the left was once a fine brick-kiln and drying sheds. Bricks of superior quality were made by J. Austin. I remember seeing Mr Symonds, an elderly gentleman, at a gypsy tea near Church Point in the year 1900; he was associated with Austin at the brickworks.

Near this spot, overlooking the water, were the residences of P. Taylor, W. G. Geddes, C. Bennett and Sir Rupert Clarke.

This has brought us to the twelfth mile-post from Manly. Along the road bordered with trees the coach descends to Figtree Flat, also known as Cape’s Flat, and the orchard of W. J. R. Baker, with “Killarney” cottage lying between the two. This flat with its green sward was a favourite picnic ground. The annual school picnic and distribution of prizes were held there on November 9 each year, the birthday of the then Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII.).

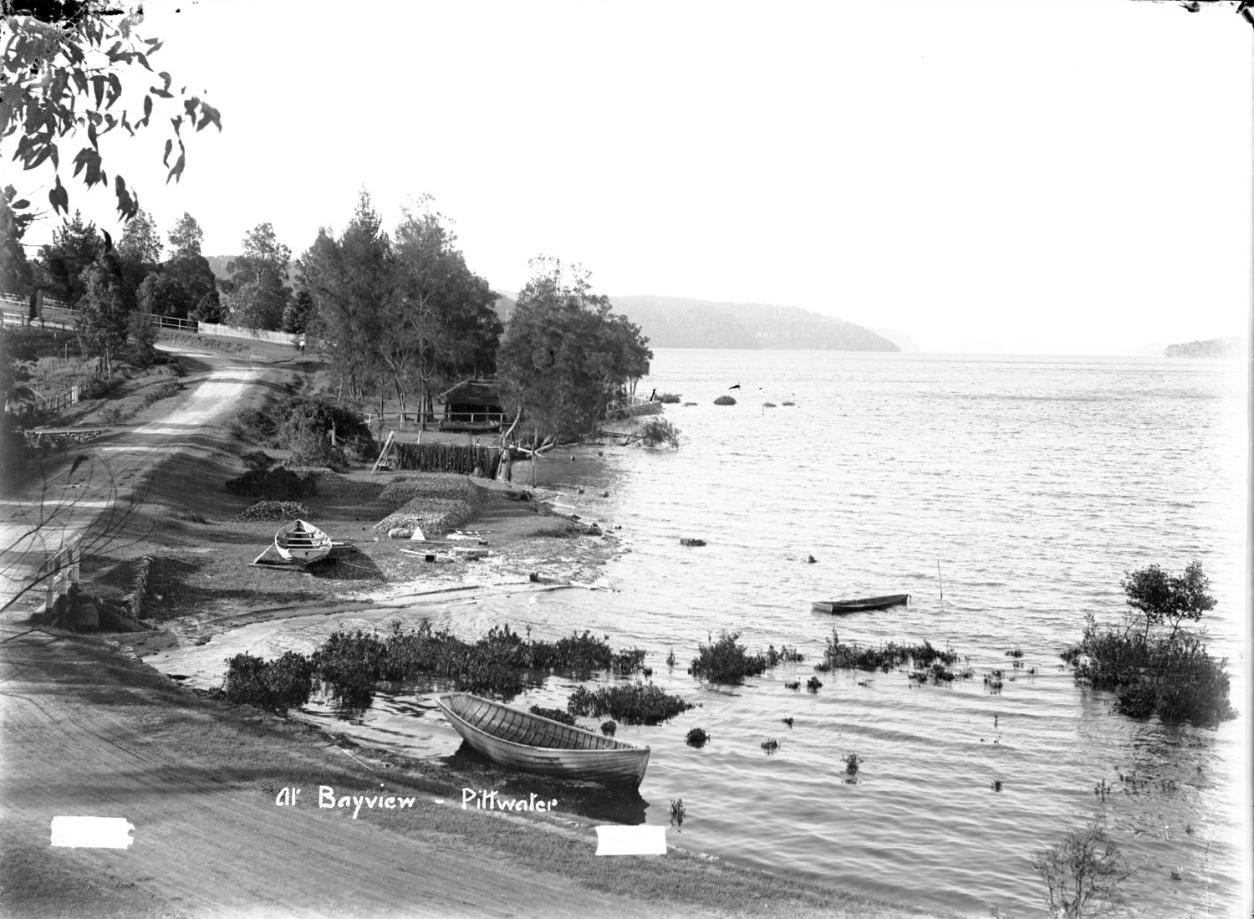

Fig Tree Flat (Capes Flat), Bayview circa 1900 - 1910

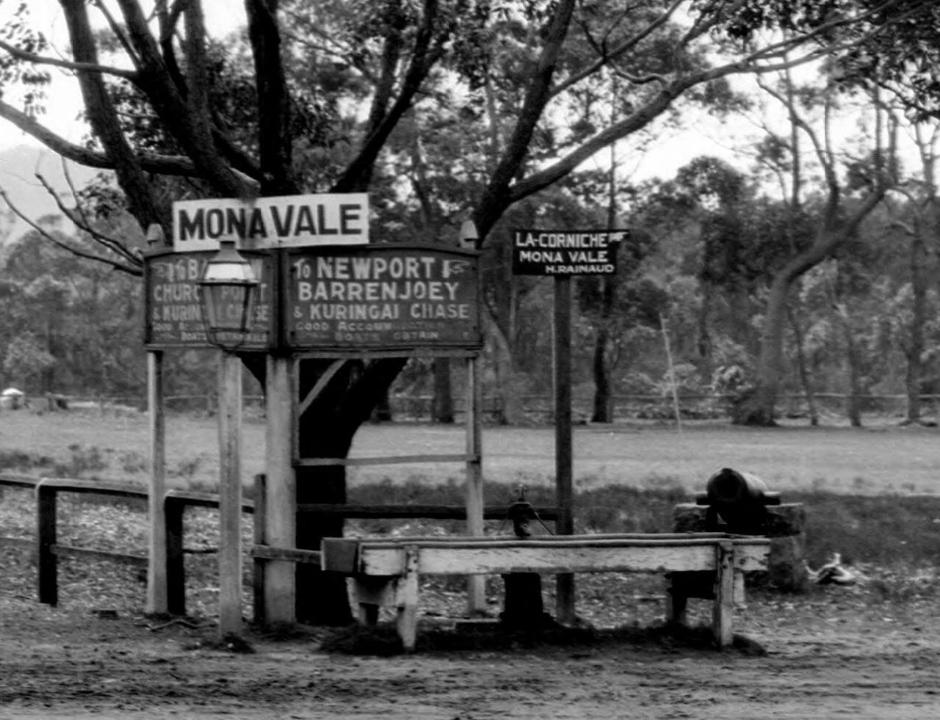

Fig Tree Flat La Corniche Bayview circa 1900 - 1910

BYRA Clubhouse is on 'Fig Tree Flat/Cape's Flat' today: the 'Fig Tree' name comes form a large fig tree that was once here - people used to gather under it for church services before the Church Point chapel was built. The other name 'Cape' stems from an early land owner, and teacher, who sold his holding.

Baker’s orchard has long since disappeared. It comprised six acres of peaches, nectarines and other summer fruits, and two acres of oranges. The orangery was situated high up at the apex of the orchard. A row of quince and peach trees flanked the fence next to "Killarney." As Baker also kept poultry, it will be seen that Bayview was once a thriving poultry-farming and fruit-growing district. - - Extract from The Early Days of Bayview, Newport, Church Point and McCarr’s Creek, Pittwater By J. S. N. WHEELER. Journal and proceedings / Royal Australian Historical Society, Vol. 26 Part. 4 (1940) Pages 88, 7905 words. Call Number N 994.006 ROY Created/ Published Sydney : The Society, 1918-1964. Appears In Journal and proceedings, v.26, p.318 (ISSN: 1325-9261) Published 1940-08-01. Available Online: HERE

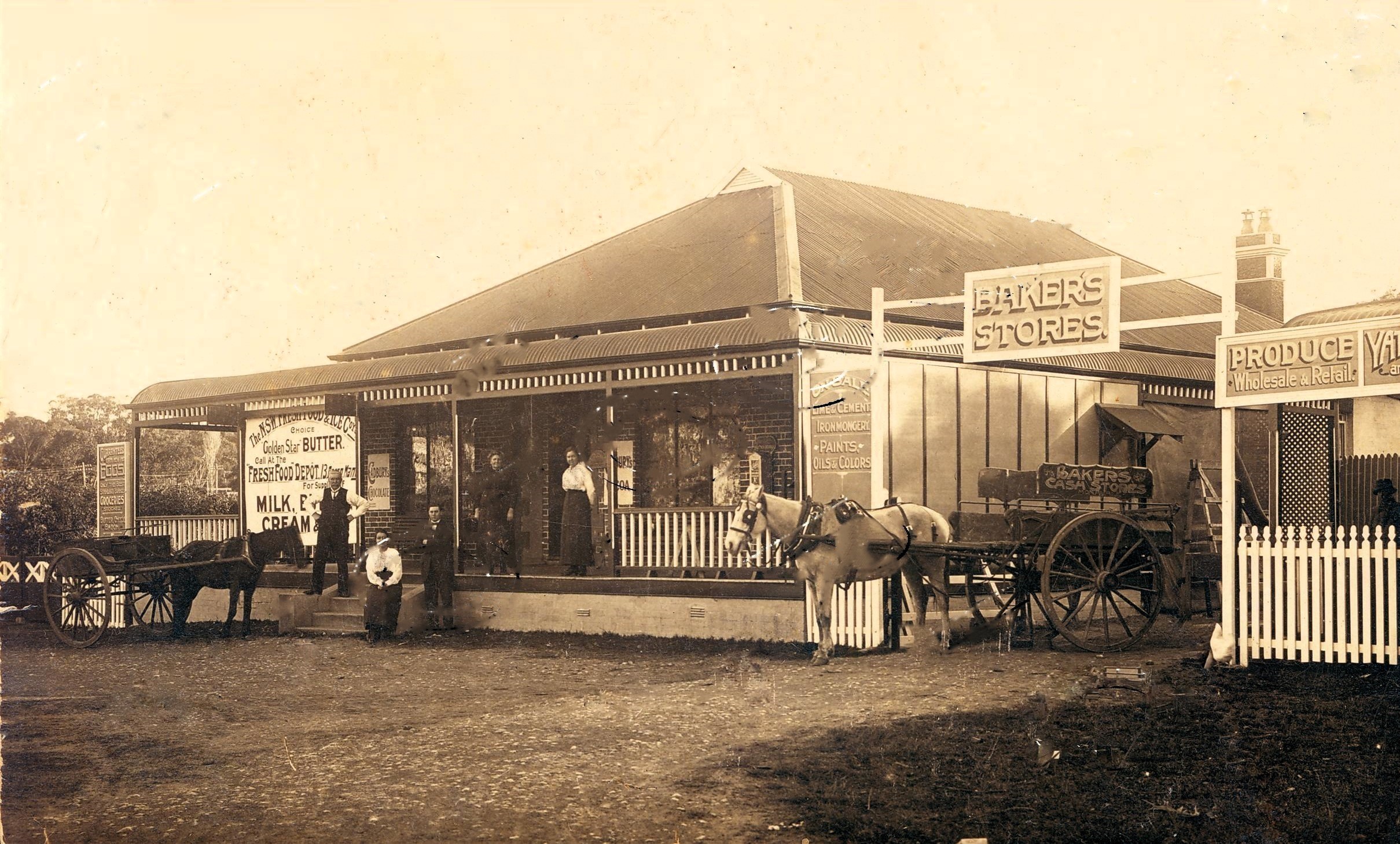

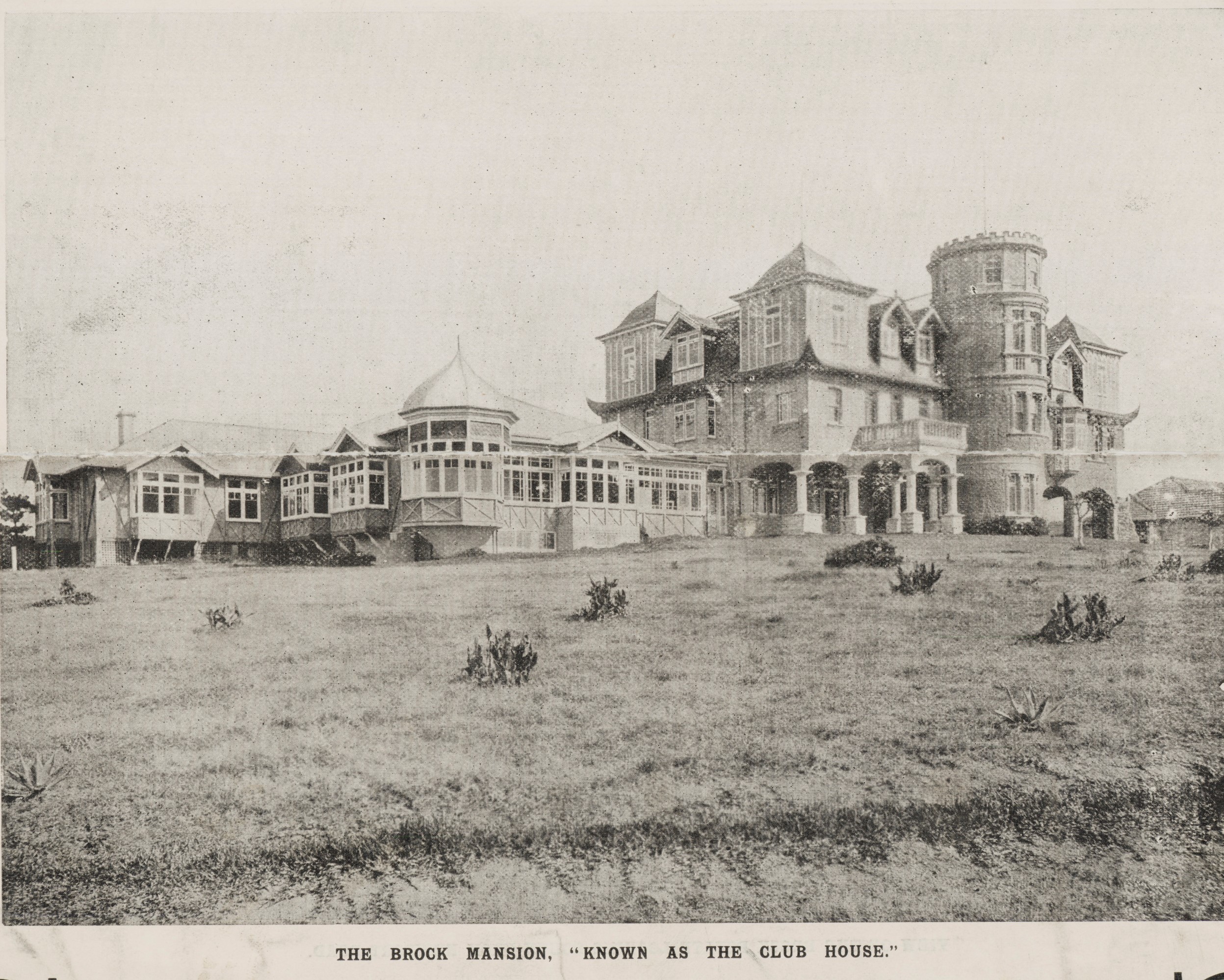

Austin's store in Pittwater road, Mona Vale, was made from their own bricks, and built around 1913 - and then run by the Savage family - section from Panorama of Mona Vale, New South Wales, [picture] / EB Studios National Library of Australia PIC P865/125 circa between 1917 and 1946] and sections from made larger to show detail.

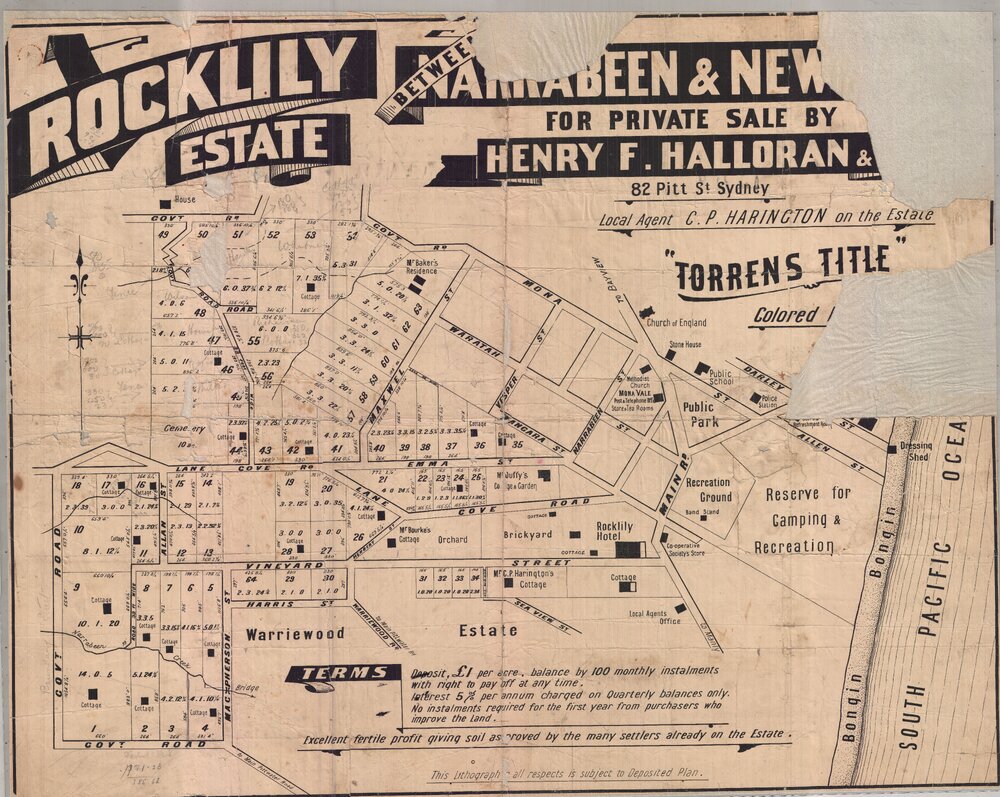

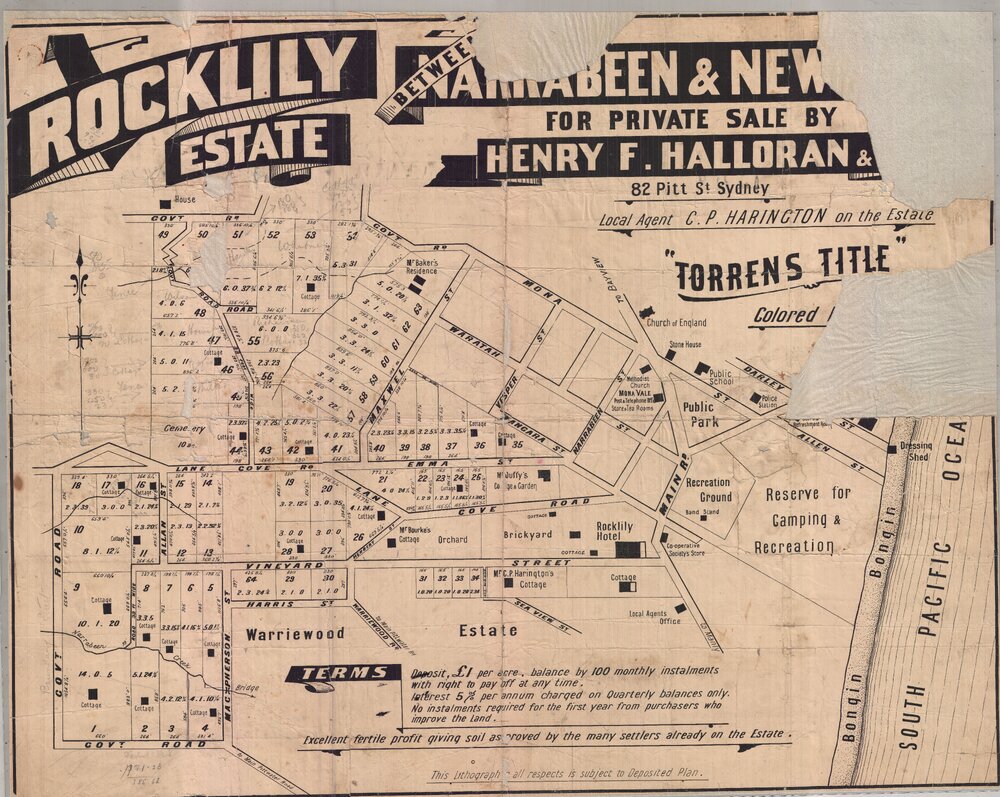

The Rock Lily also had a Brickworks at the back of the premises, which shows up in this 1925 private sale of the land lithograph:

Vol-Fol 2762-161 - Rock Lily's last 5 acres being sold:

.jpg?timestamp=1770845756555)

.jpg?timestamp=1770845804830)

NB: what is called above 'Gordon road' is today's Mona Vale road - it was then called 'Gordon road as it was the 'road to Gordon' - earlier there had been a 'Lane Cove Road' for a section of this, as it was 'the road to Lane Cove'.

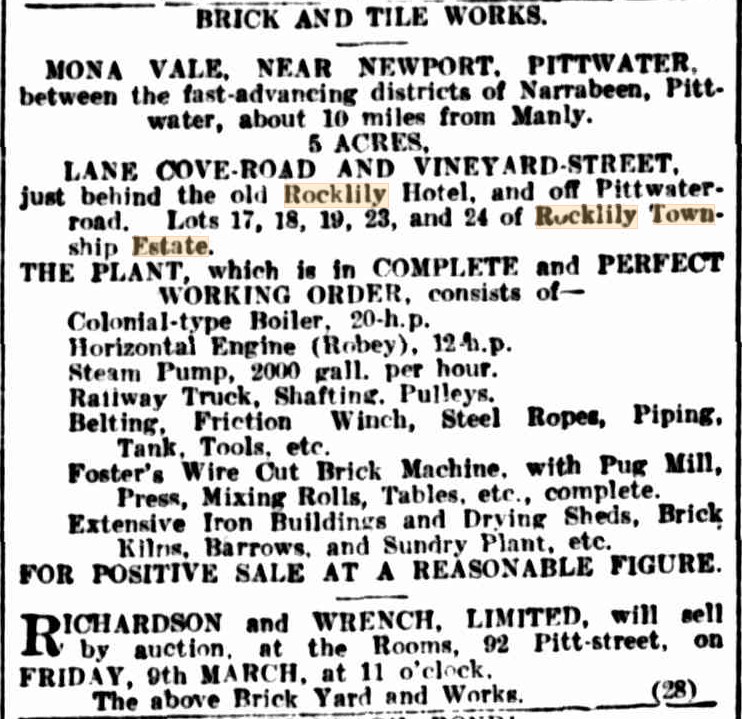

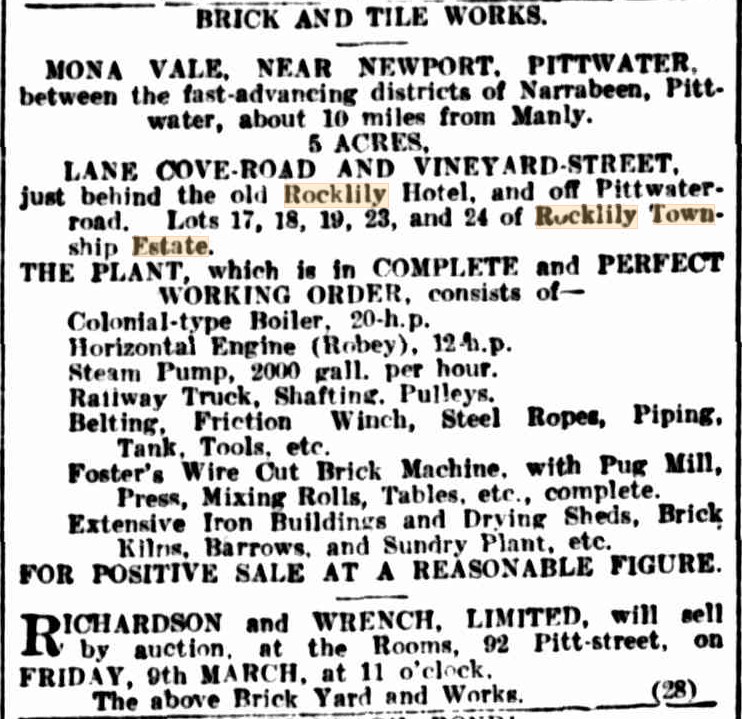

A 1923 description of the Rock Lily Brickworks:

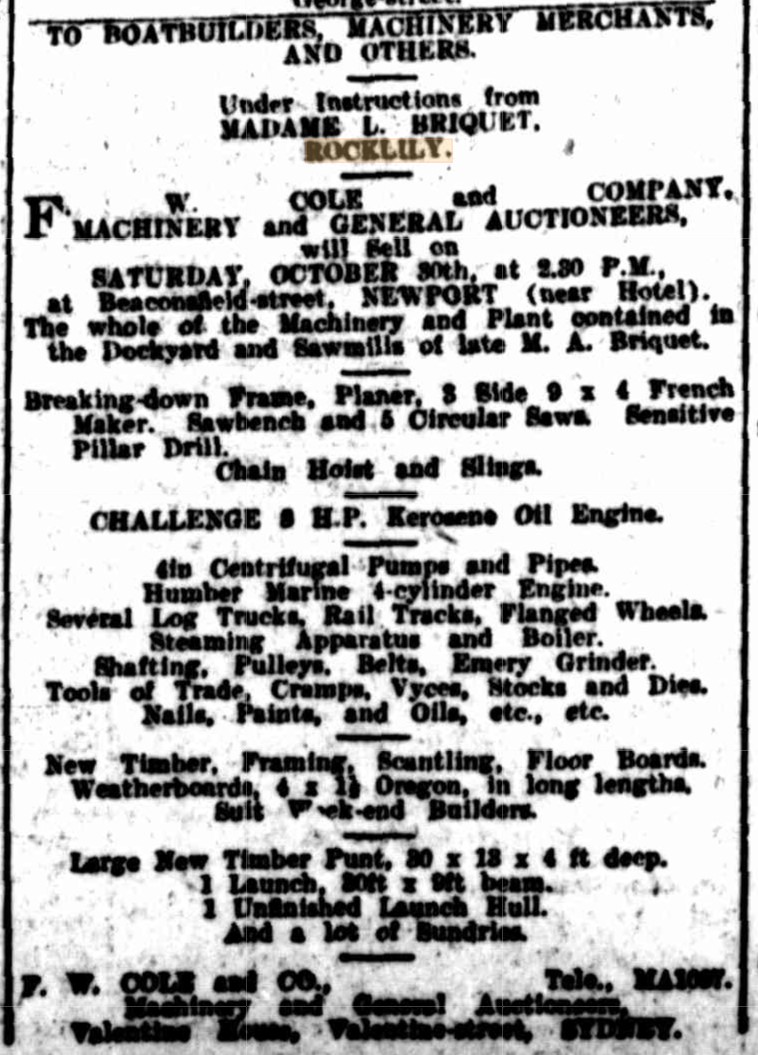

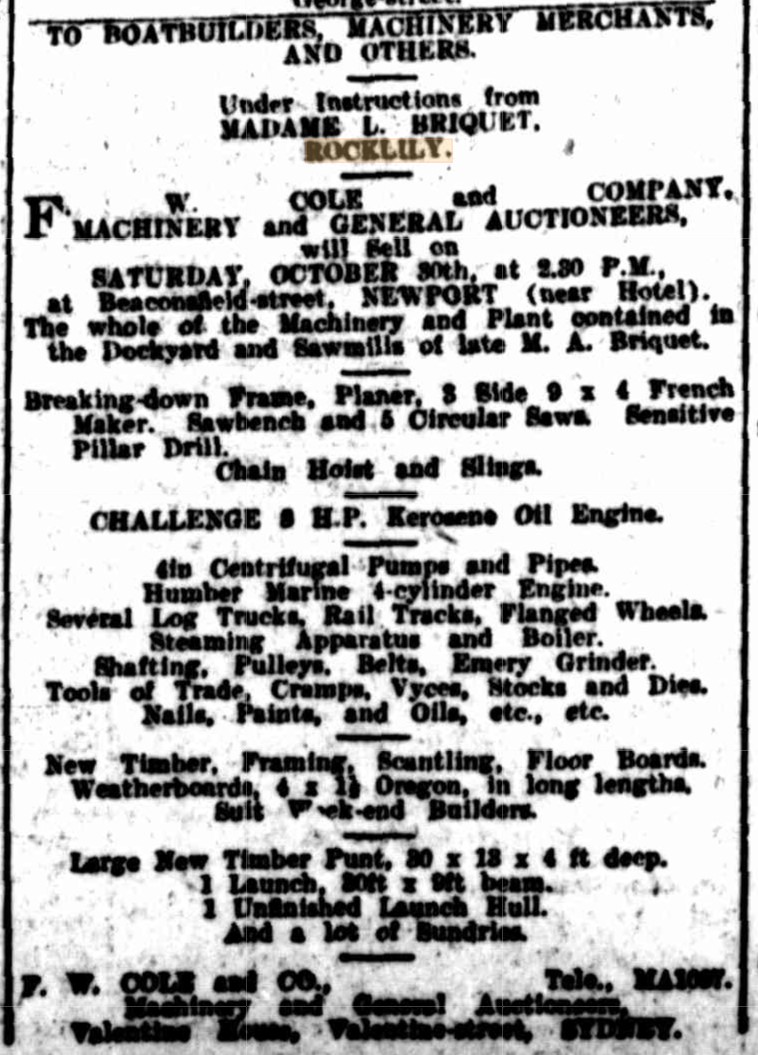

Auguste Briquet, who married Justine, the daughter of Leon Houreaux who originally built and owned the Rock Lily back in the 1880's, passed away - and she began trying to sell off some of the DIY ventures he had gone into - in 1926, at Newport, for example:

Auguste and Justine Briquet inside the Rock Lily. From State Library of NSW Album: Portraits of Norman and Lionel Lindsay, family and friends, ca. 1900-1912 / photographed chiefly by Lionel Lindsay. Image No.: a2005209h and below: a2005210h

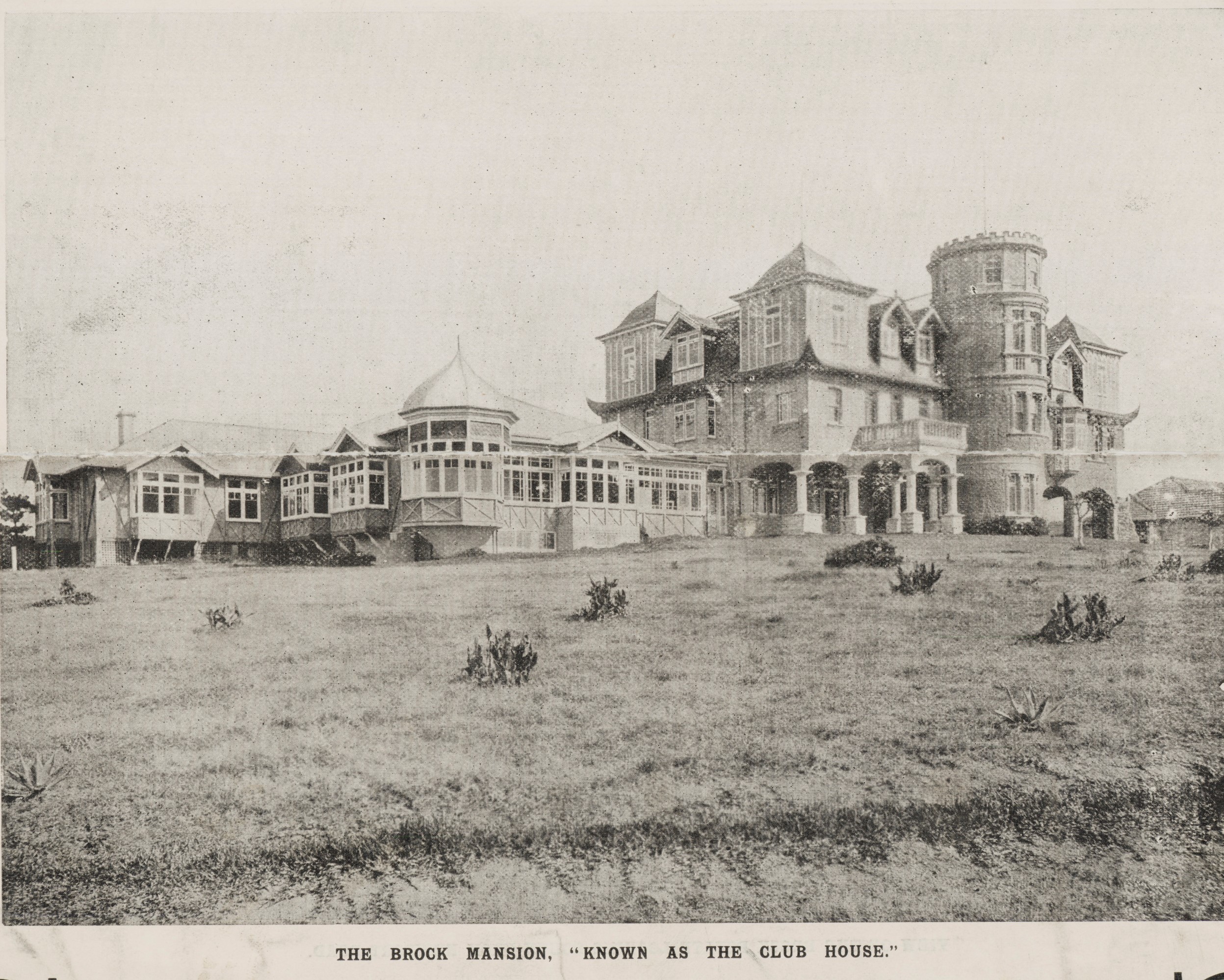

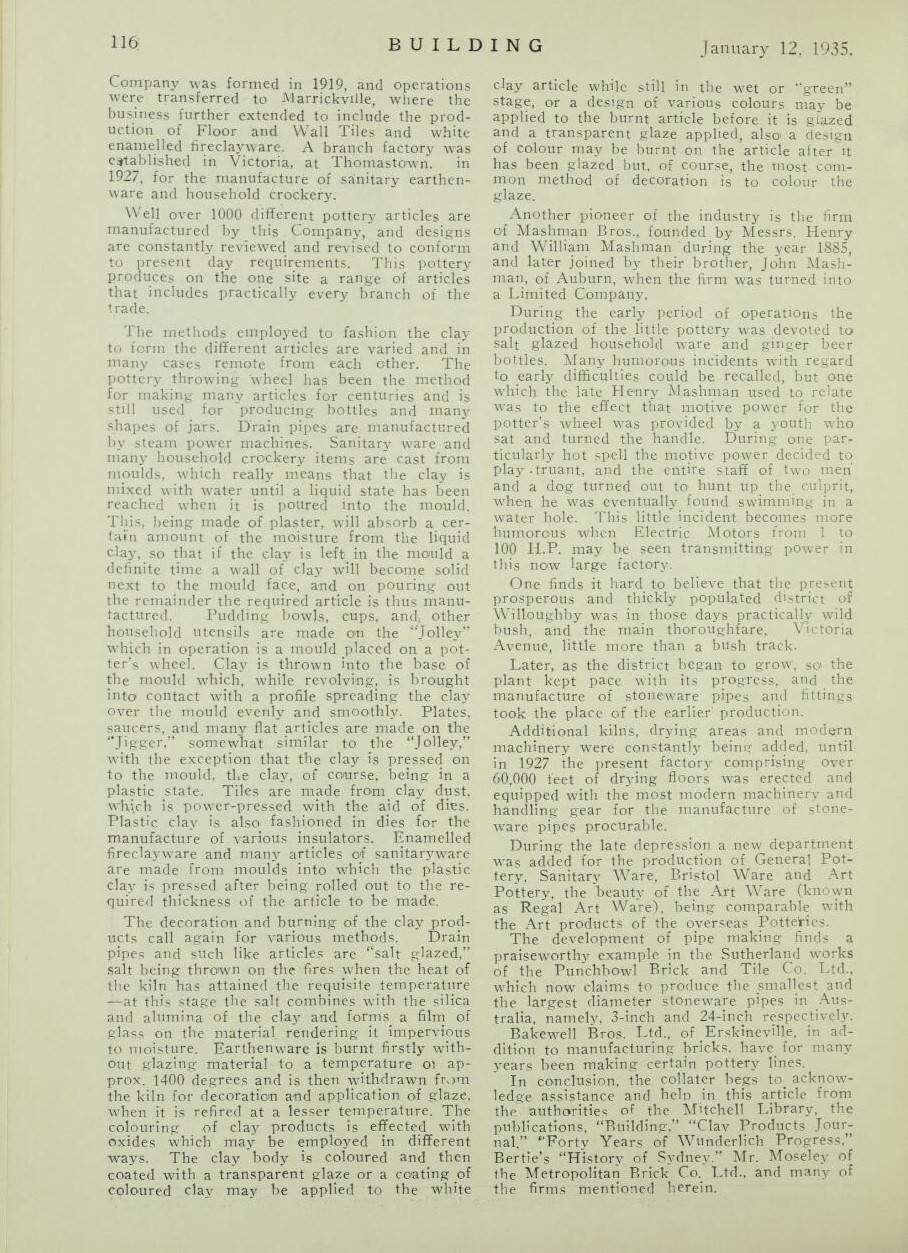

Another local brick-maker was George Brock, who stated his own brickworks to build the now gone 'Oaks' on Mona Vale Beach, which was rebuilt in the early 1920's and took on the name it had after Mr. Brock as 'La Corniche'.

Both James Booth and Samuel Stringer, residents of Mona Vale who lived around today's Village Park, worked on the construction for this resort. Mr Stringer had a few problems when he was sourcing bricks from elsewhere:

TO BRICKLAYERS-Wanted, PRICE per thousand. Particulars by letter or personally from S. STRINGER, Mona Vale, via Manly. Advertising. (1904, March 16). The Sydney Morning Herald(NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 5. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article14606738

DISTRICT COURT. (Before Judge Heydon.)

DISPUTE AS TO BRICKS. Moore v Stringer.

Mr. H. C. G. Moss appeared for the plaintiff, and Mr. Carter Smith for the defendant. This was an action brought by Ellen Moore, of Manly Vale, Manly, wife of James Arthur Moore, against Samuel Stringer, sen., of Mona Vale, near Manly, to recover the value of 7050 bricks, alleged to have been used by the defendant without plaintiff's authority. The defence was that the plaintiff's husband had been paid for the bricks, and had given defendant a receipt, but plaintiff contended that her husband had no authority in the matter. His Honor said It was quite clear that the bricks were the property of Mrs. Moore, and not of her husband. Verdict for plaintiff, £10, but no order made as to costs. DISTRICT COURT. (1905, February 8). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 5. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article14672752

"Mr. Stringer bought 6 adjoining blocks of land in Park Street Mona Vale for 125 pounds, which formed section 1 of the Mona Vale Estate. The vendor was Hon. Louis Francis Heydon and the sale was transacted on 21/07/1902. On 23/10/1903 Stringer borrowed 200 pounds from Heydon “for the purpose of building on the land”. Building is thought to have commenced in 1904. He also built the imitation sandstone cottage next to Dungarvon, No. 26 Park Street. In 1922 Stringer was over 70 years old and sold up Mona Vale and moved to Hurstville. He died in 1931." - Guy & Joan Jennings – Mona Vale Stories (2007)

Dungarvon as it was a few years back - on Park Street Mona Vale

'Brock's' 1907, showing what would become the Barrenjoey Road.

'Brock's' circa 1907, from beach front

An 1904 report states:

There is an Art Gallery Also in the buildings, where Mr. Brock, junior, plies his capable brush. The walls are covered with his pictures, all showing marked talent. On the way from America, the land of novelty, is A Sculpturing Machine, which a skilled operator can make facsimiles of a human face simultaneously. From the photographs of the it is a wonderful affair, costing a pounds. The marble busts can turned out very fast and cheap,—say 5 or 6 hours for about a pound a piece' quite knocks out hand work—but it requires a hand to guide the rapidly cutting chisels, and the hand of an artist in order for good results. A sculptor, however, can with one of these machines of much better work than with the hand only. The instruments that do the out- resemble somewhat the little cutters dentists use to bore out teeth for stopping. They have only to be moved over the marble slowly and the lifelike image is graven. When the tram was started from Manly Mr. Brock put on about 200 Men to get the place ready, but when that fine project fell in pieces he took most of the men off again. He keeps a brick kiln going constantly, and there are always men employed building.

Some day " The Oaks " will be the name of one of the finest health resorts in the world,-meantime it is a most comfortable and beautiful home.

“THE OAKS,” (1904, September 3). The Mosman Mail (NSW : 1898 - 1906), p. 4. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article247008613

Extracts from one from 1910, when the state government had decided to run the place, says:

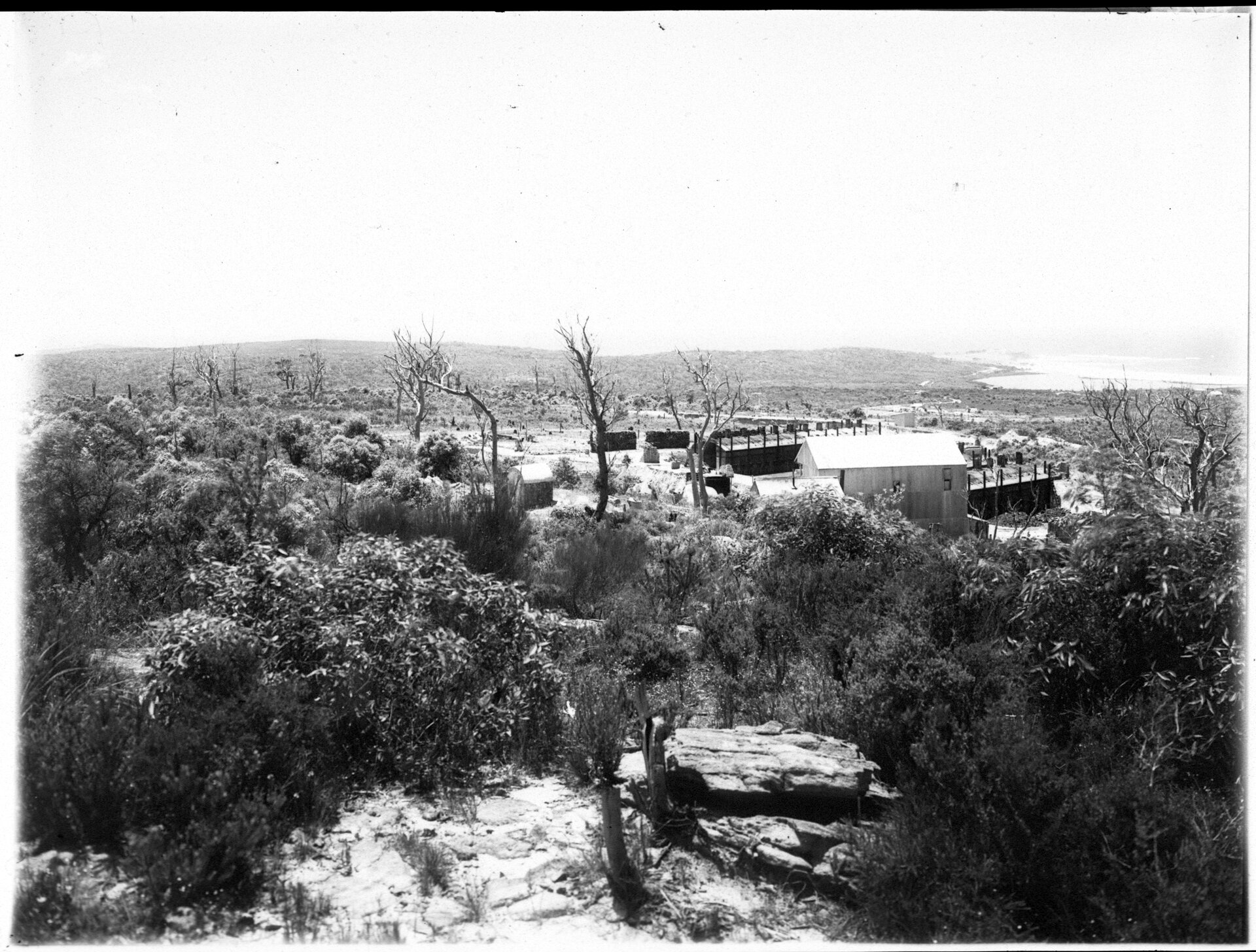

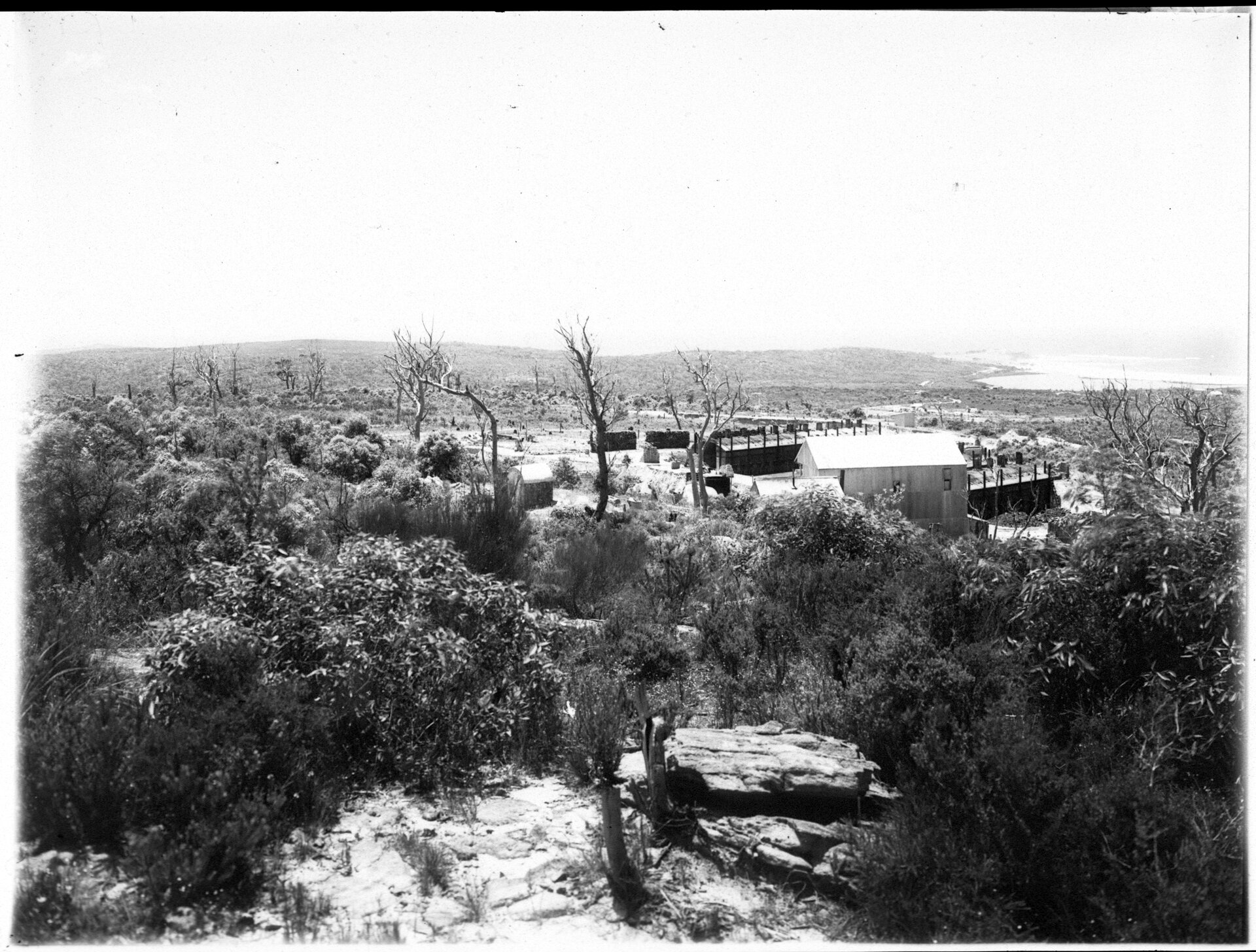

THE GREAT IDEA. And the idea was this: To build a huge village upon the drained lands of the estate, dominated by a magnificent clubhouse, and to sink £25,000 in the realisation of this immense scheme. To prove a financial success, access by tram to the estate was the one thing absolutely necessary. And this the Government had promised. The Man with the Idea set about the carrying out of his .purpose on a splendid scale. On the site he erected his own brickworks for the manufacture of the bricks and tiles: he bought a timber area at Erina Creek, on the Hawkesbury River, installed a timber mill and a planing machine as well, and so cut, freighted, and treated his own timber on the spot. He worked his own quarry, drawing from it all the needful stone, drained the swamp, obtained a regular water supply by the construction of a great brick and cement tank,' 20Ct. wide and 14ft. deep, and Installed a complete sewerage system. And all the while the promised tram was creeping out from Manly, slowly but surely. By the time it had reached Curl Curl, 12 months after its start, the walls of a mansion, or rather of a group of mansions, at Mona Vale were roof high, and the great idea was flowering in wood and stone and brick towards completion and perfection.

BROCK'S ESTATE FROM THE HYDRO.

ANOTHER VIEW OF THE HYDRO.

WHERE TO SPEND THE WEEK END. (1910, December 25). The Sun : Sunday Edition (Sydney, NSW : 1910), p. 11. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article231015197

La Corniche circa 1911

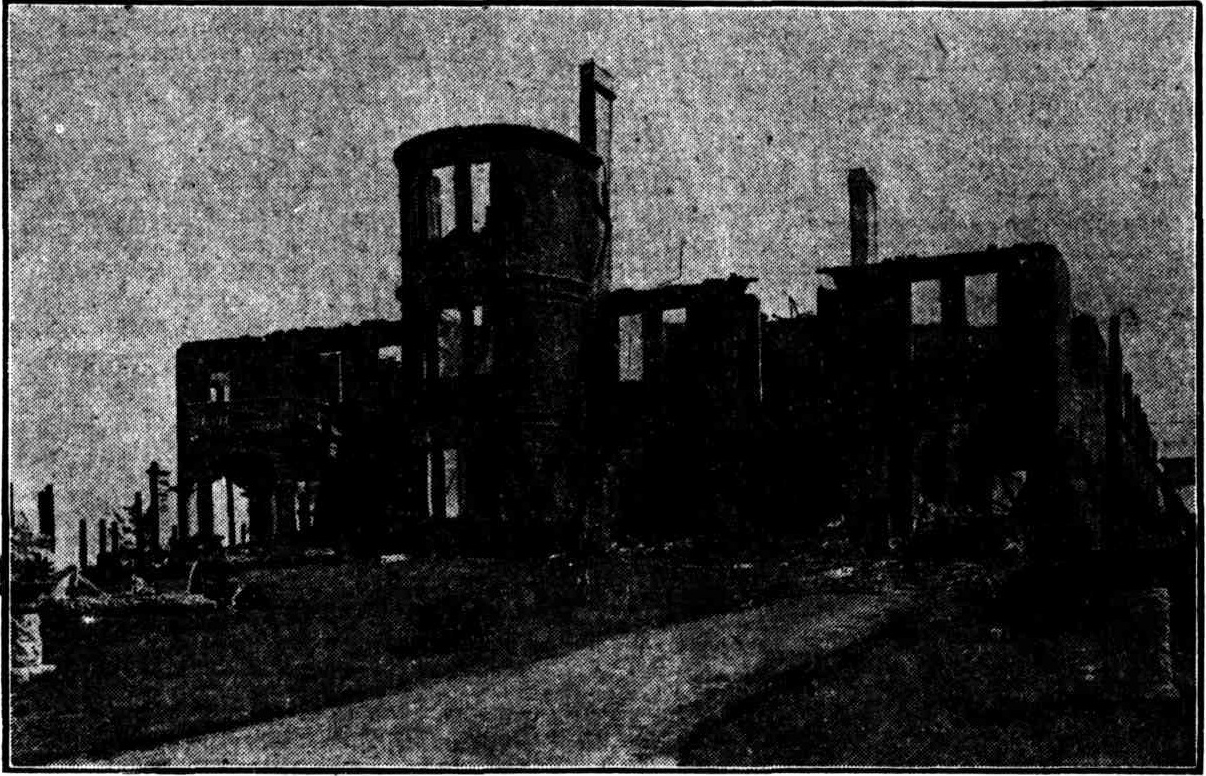

A report from 1912, when a fire destroyed much of the main building, tells us:

AN UNLUCKY BUILDER.

man who was before his time.

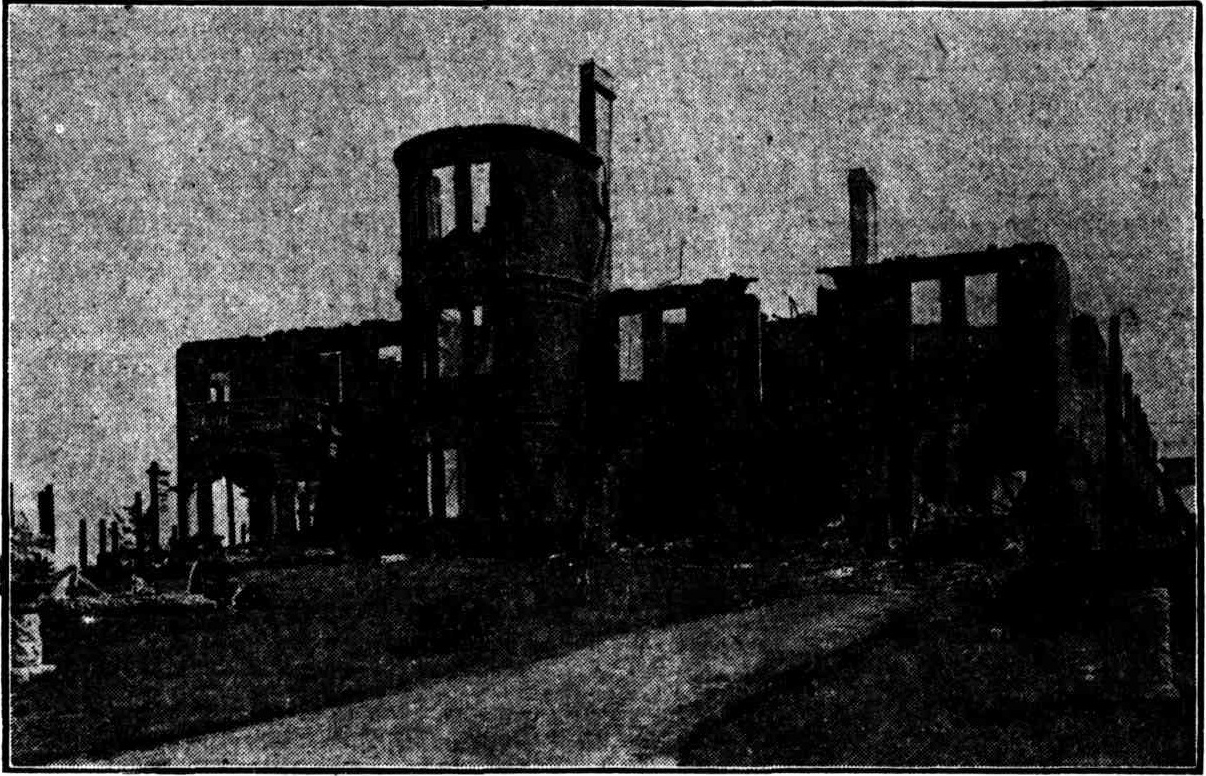

The total destruction of the beautiful "La Corniche," better known as Brock's Mansion', at Mona Vale, in the early hours of this morning robs the naturally beautiful tourist journey from Manly to Pittwater of one of its, leading attractions. This magnificent pile of buildings, with Its charming surroundings, has always excited the admiration of the traveller, and the story of Its building by Mr. Brock, and its passing out or his hands after all his Napoleonic' work, has, always won- the stranger's keen sympathy. Mr. Brock gave the best years of his life to the realisation of his Idea to provide a high-class hotel on the lines of a great country home on this unrivalled site, which provides all the delights of ocean, lagoon, and green hills. His-choice of a spot could not have been Improved on with Its glorious ocean views, and after great work in levelling and draining what was a great swamp he evolved a fine polo ground and racecourse on the flat. Six years ago there were no less than 44 polo ponies on the ground.

When Mr. Brock started the buildings he set up his own brickyards and sawmills. Everything he used came from his district In this connection he showed his patriotism by employing only local labor, and for several years he was a benefactor to the neighborhood, his expenditure going Into many thousands.

It may he said that before Mr. Brock started his great undertaking he had the assurance of the Government then in power that the tram to Pittwater would be constructed at once. He went on with his work, spent many thousands, and just when he was within reach of his goal his money ran out, and he lost all his claims to the property, and the results of his labor for years. AN UNLUCKY BUILDER. (1912, January 8). The Sun (Sydney, NSW : 1910 - 1954), p. 1. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article222004175

Ruins of "Brock's Mansions," at Mona Vale, destroyed by fire on Monday morning. The fate of the handsome pile of buildings is a grim finale to the financial tragedy that overtook the plucky builder, Mr. G. S . Brock, in its erection. No title (1912, January 10 - Wednesday). The Sun (Sydney, NSW : 1910 - 1954), p. 1 (FINAL EXTRA). Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article222002216

as 'La Corniche' [exterior view] circa 1920 - 1927 Image No.: a105577, courtesy State Library of NSW circa 1920-25

An earlier form of Mona Vale SLSC, when it was Mona Vale Alumni during 1930-31, used this premises as their weekend base. As can be seen below, the place was still used as a resort for visitors:

After Brock's Manion was finished, a few years on, another prominent brick-person came to Mona Vale and built brick cottages where land was later resumed to build Pittwater High School. The site for the school was resumed in 1961.

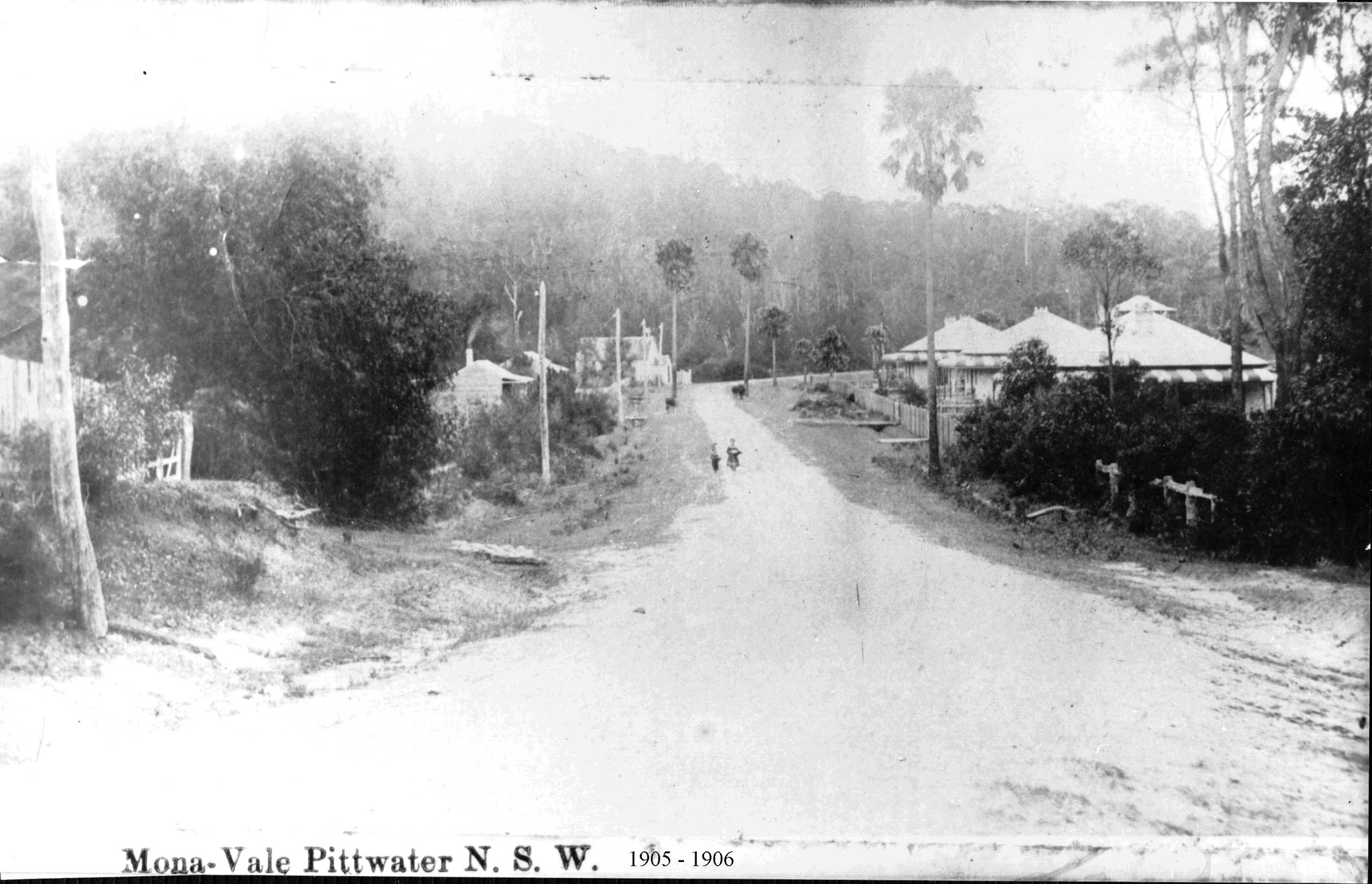

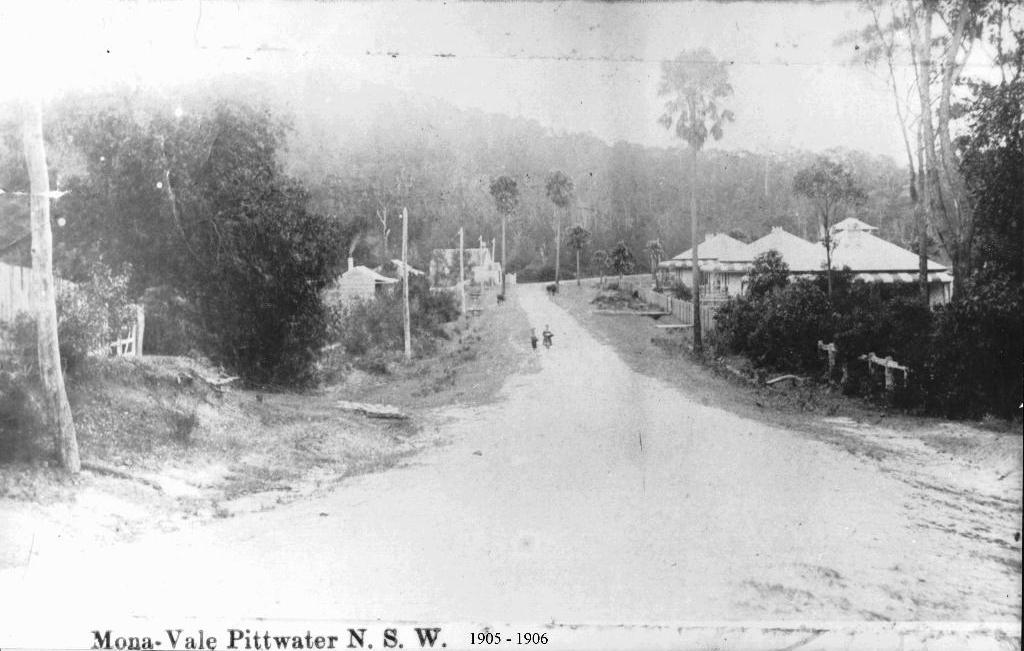

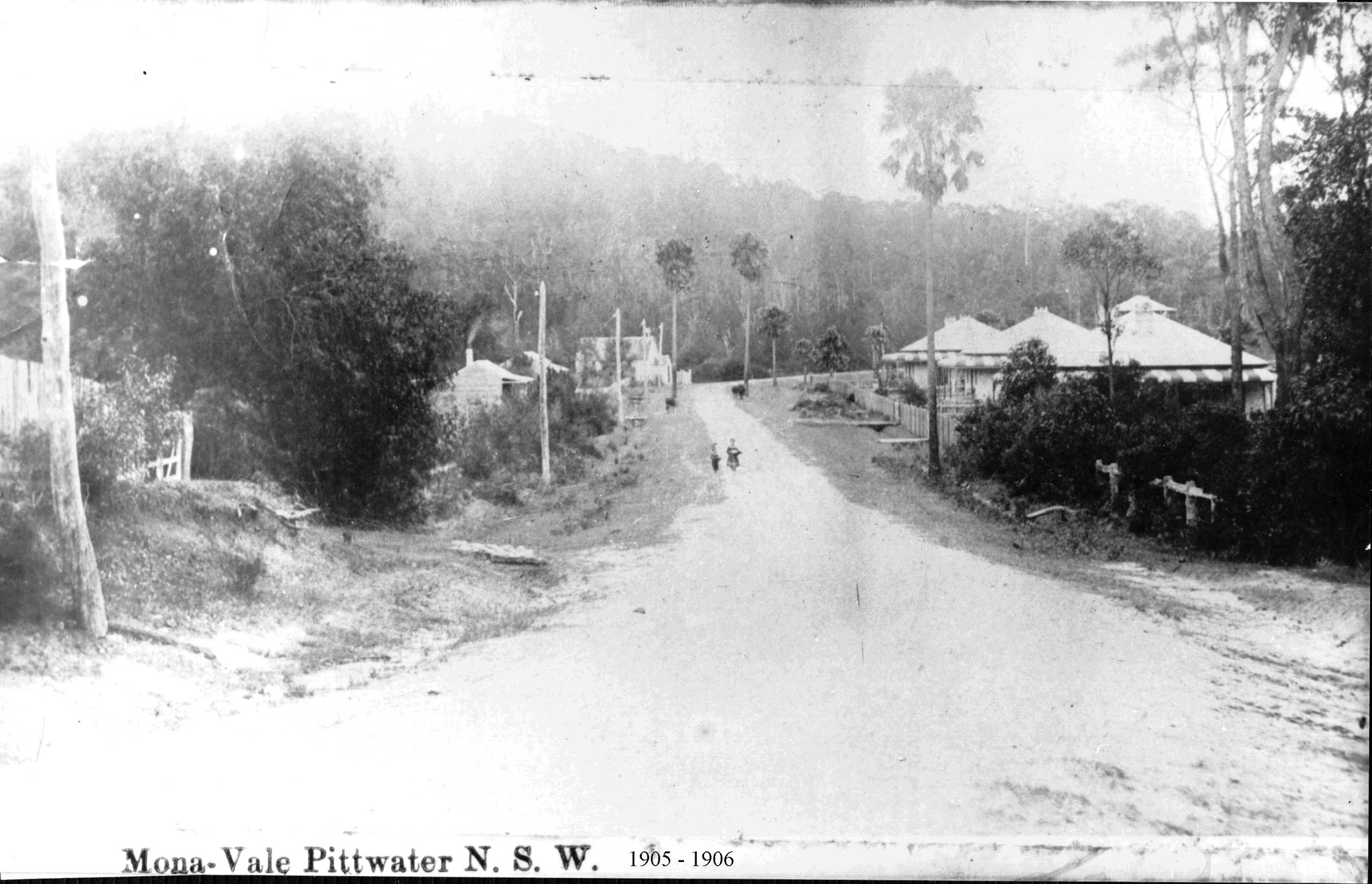

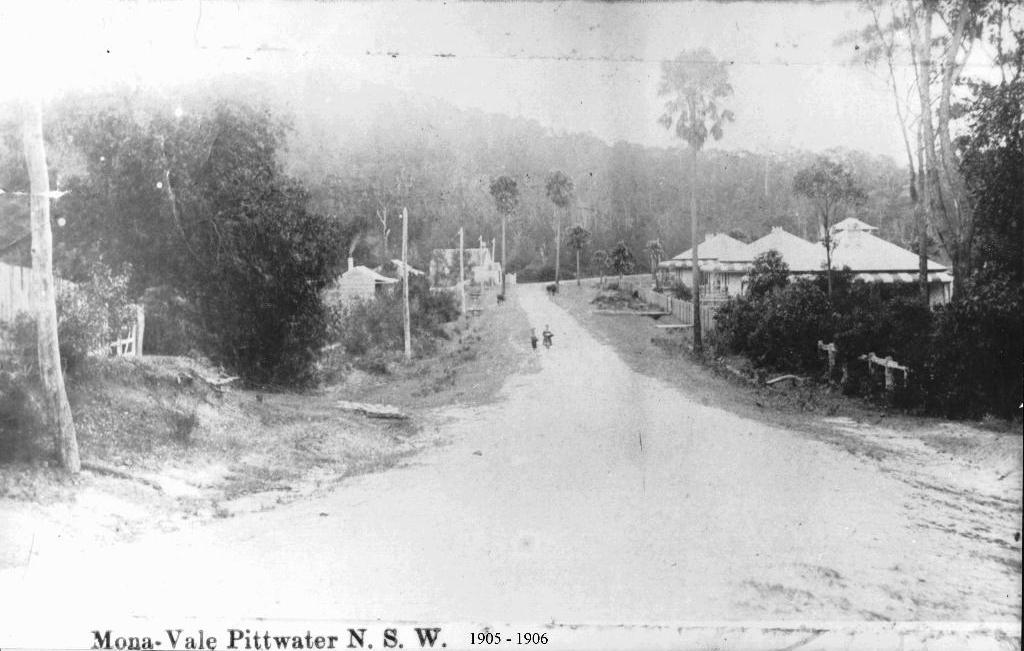

Top photo: Bay View Road Mona Vale circa 1900-1905(current day Pittwater road right to Bayview and Church Point) looking north from Mona Street. St John's Church can be seen to the left of the photo - this had been moved there from the Mona Vale north headland in 1888. By 1904 the wooden church had deteriorated to such an extent that it had to be demolished and a small stone church was built by James Booth on the present site at 1624 Pittwater Road Mona Vale, much closer to the village centre and was built in 1906 and opened in 1907. The residents raised funds by holding entertainments in the now demolished 'Booths Hall' at Mona Vale as well as by other means.

The cottage at the right front, which appears to have a turret, is actually James Shaw's house on the hillside above the corner of Cabbage Tree and Bayview roads. The two Cabbage Tree Palms marked the old border between Bayview and Mona Vale.

Above; the Bayview road looking south towards Mona Vale. Mona Vale was once called 'Rock Lily'; people born in the area even into the 1920's had their birthplace recorded as 'Rock Lily'. Images from State Library of NSW and State Library of Victoria

Mark Horton, whose family have lived in the Mona Vale and Bayview areas for four generations, shared:

'The land in the top photo, right hand side, is the stretch of Bayview Road, now Pittwater Road running past the now Pittwater High School site. The houses on the right were on the Pittwater High School site and were demolished in an early morning clandestine action by the Department of Education in the early 1970s. Instead of preserving a bit of local history on the school site two houses with historic significance were demolished. The area where they stood is still green space.'

Guy and Joan Jennings 'Mona Vale Stories' (Arcadia Publishing Newport NSW, 2007) records:

On the eastern side of Bayview Road here were three cottages. They were built by Tom Arter who was commissioned by the Esbank Estate in Lithgow to build them as Show Houses. Tom's grandson, George Johnson, recalls that the bricks came from the Wilcox family in Bassett Street, however a Mr. Shreinert remembers the bricks coming from the kiln near the Rock Lily (hotel). The roofing iron was delivered by steamer to Bayview Wharf. There is some evidence to suggest the cottages were let for short term holidays. However for most of the time they were associated with a number of permanent residents'.

The northern most at 1686 Bayview road was called 'Eskbank', a name that came from an old house at Lithgow. This is the cottage that Louisa Dunbar came to in 1909 after the death of her husband, with he three children. She ran the bakery there until the Maiseys took over around 1913. The Maiseys stayed until their father George died in 1931 and most of the family returned to Parramatta. Henry 'Joe' Johnson and his family became the residents during 1938-1940 and he worked as a groundsman at Bayview Golf Course for 47 years.

The family that spent the most time in the house were the Lewis' who bought the property in 1946 and stayed until 1973 when they sold to Mr and Mrs Symonds who planned to restore the home. It was demolished in suspicious circumstances in 1978.

The middle cottage, No. 1682, was owned by Sam, and Mabel Perry from around 1916 until the 1960's when it was taken by the Education Department and demolished.

The southernmost cottage, No. 1678, closest to the corner of Mona Street, was first owned by Richard and Margaret Reid. The next resident was John Thomas Hewitt, policeman and Shire Councillor who later owned the Mona Vale Hotel site, where they built a home, and acreage along present day Golf Avenue. This was then taken over by the Shreinert family who at one time ran refreshment rooms here.

In 1961-62 the Education Department resumed around 2 acres each from the three homes; Lewis', Perrys and Shreinerts, leaving around half an acre to each house. When Mabel Perry passed away her house and remaining and were sold to the Education Department and the house was quickly demolished. By 1973 both the Lewis' and Shreinerts were weary of living surrounded by the school yard with no proper fences. The Shreinerts sold to the Education Department, and as recorded above, they sold to the Symonds, who also found the site too much and also sold.'

Local lore states that, keen to stop a heritage listing for this last cottage, which it was of course, the Department knocked down Eskbank on the October long weekend of 1978.

The land resumptions, officially published in the NSW Government Gazette, shows 15 acres were resumed at first - all part of the land bought by the Mona Vale Land Company from the Darley estate. More in: Pittwater High School Alumni 1963 To 1973 Reunion For 2023: A Historic 60 Years Celebration + Some History

The Warringah Shire Council took money for people taking sand to make bricks with, although when they had their own plans to reclaim land at Bayview to form parks, they began to change what they would allow and when - it's worth noting that the state government also had to approve such leases as the estuary is 'Crown Land' or more accurately, crown waters:

BRICKS FROM SAND

Warringah Shire Council decided last night to grant a special lease to Composite Brick Pty. Ltd. for the dredging of sea sand at Bayview, Pittwater.

The sand will be used to make clay-cement bricks. It will be taken from areas in the Newport channels that have been silted up by previous dredgings.

The Council rejected a proposal that a special lease be granted for an area at the head of the bay which the company is willing to reclaim by dredging. The company wanted to build a factory on the reclaimed land. BRICKS FROM SAND (1947, September 3). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 4. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article18041363

Brookvale Brickworks at Beacon Hill

Brookvale Brick works actually was at Beacon Hill. These brickworks used clay from quarries on Beacon Hill which became a medium density housing development after its closure in 1996.

Section from Beacon Hill to Brookvale panorama, circa 1900-1909 courtesy NSW Records and Archives

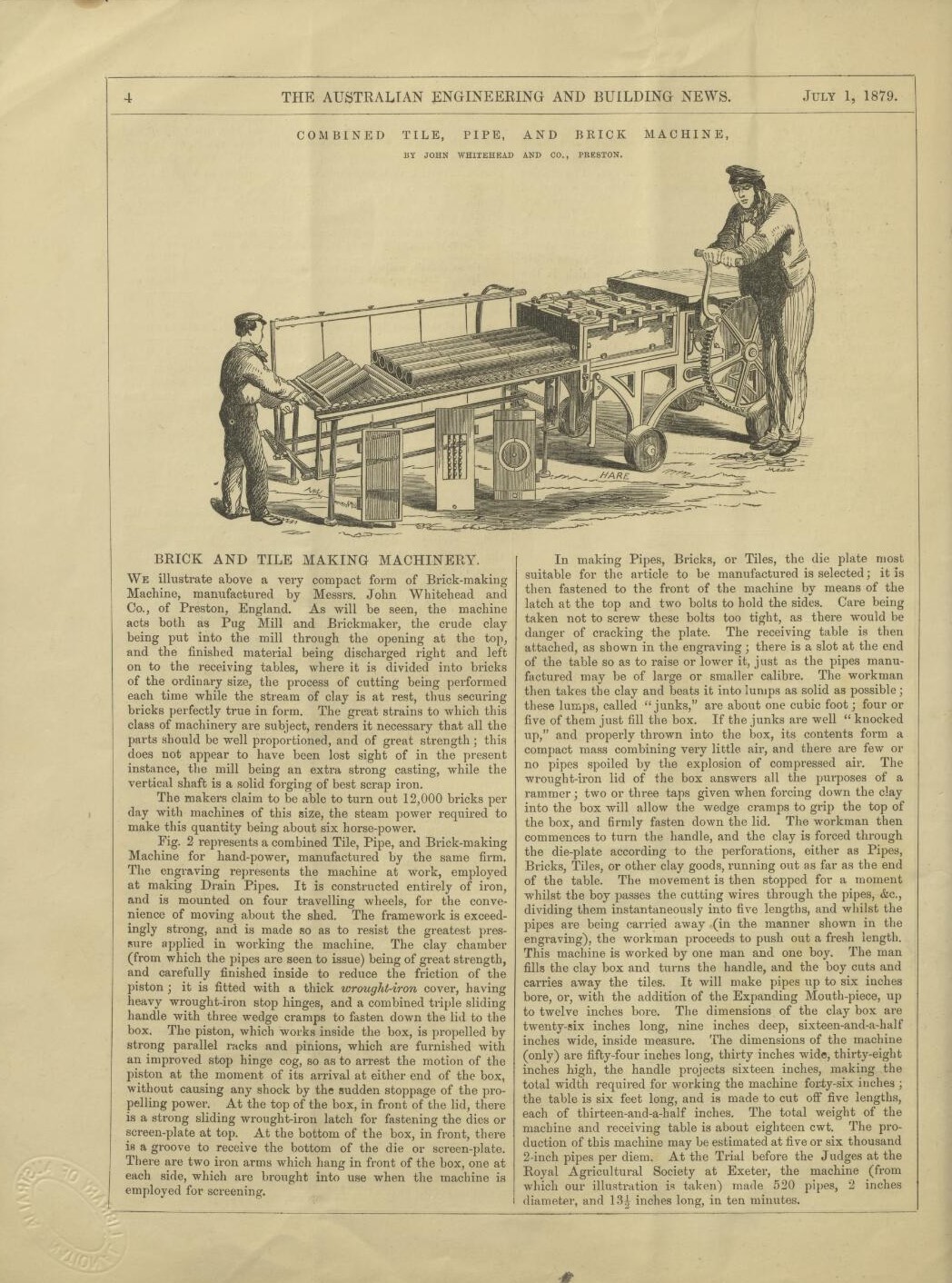

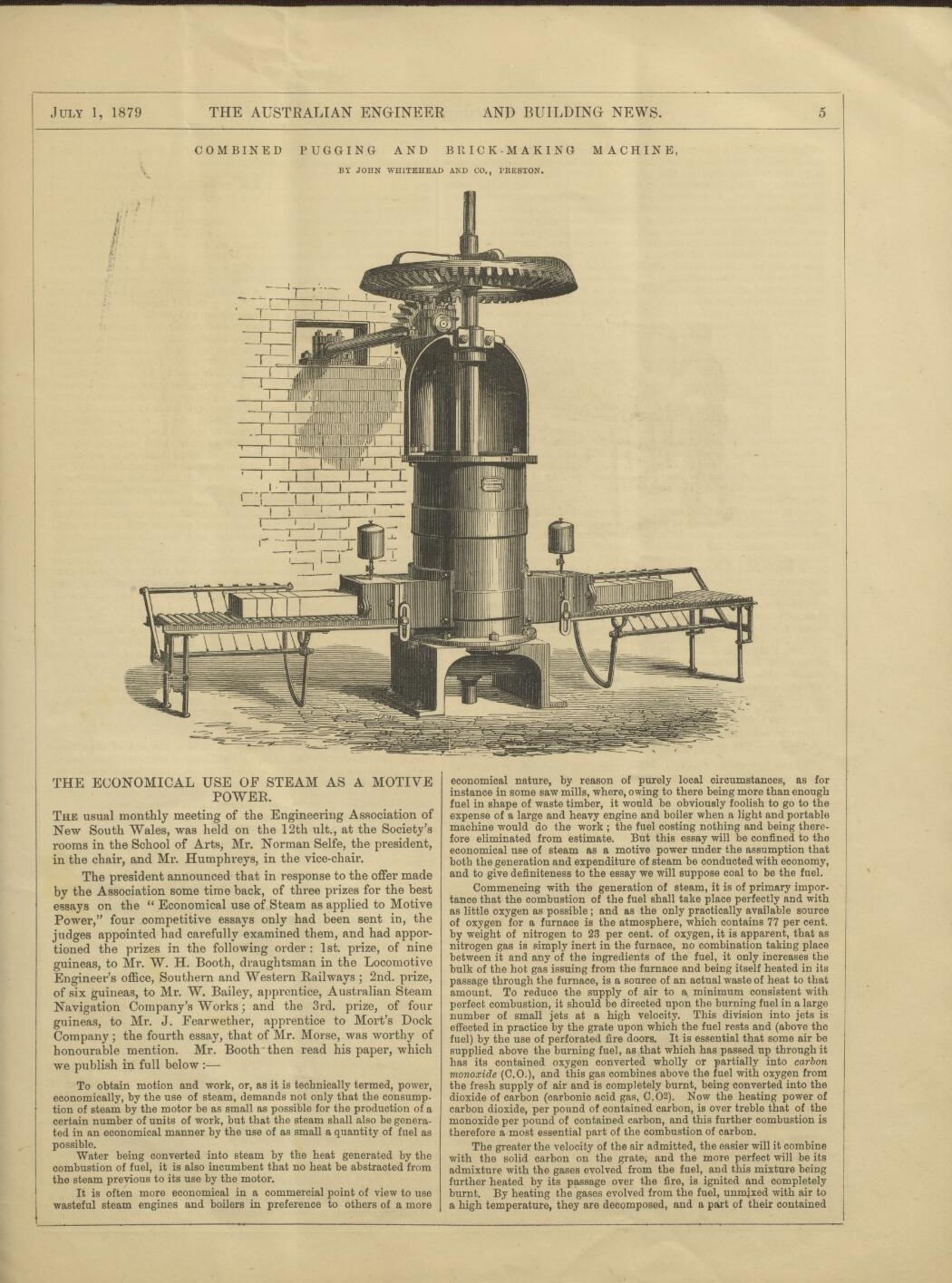

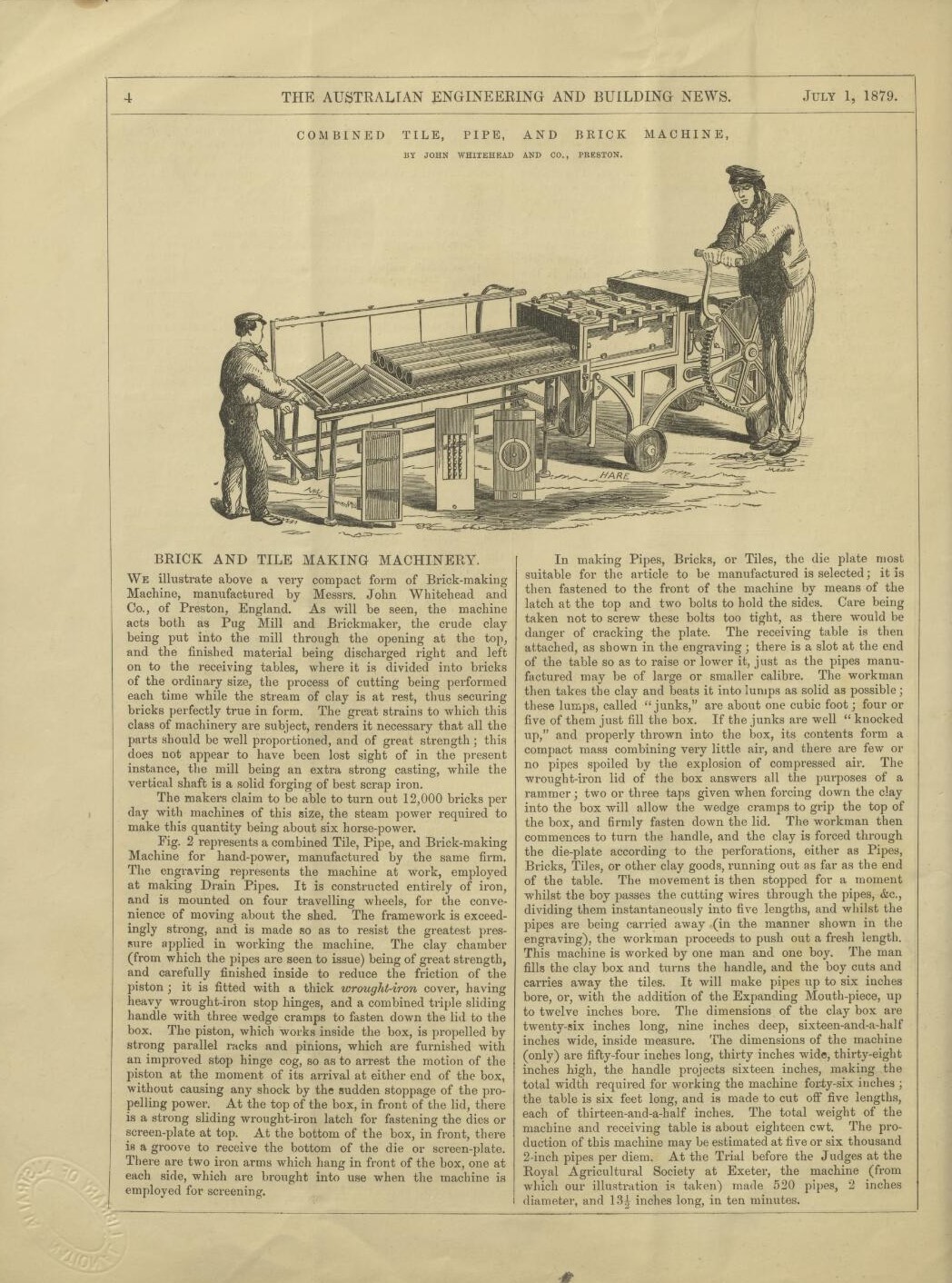

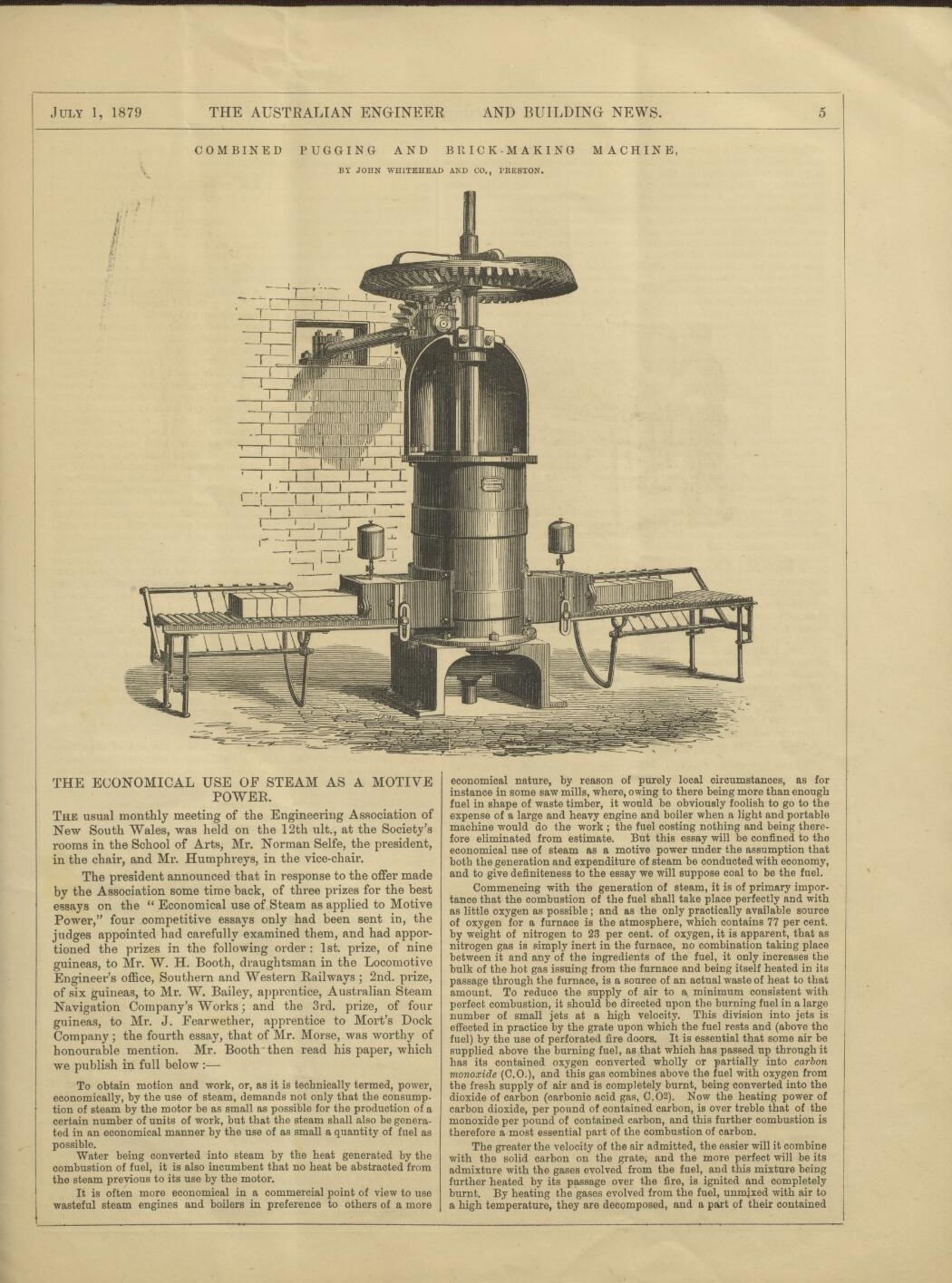

We tracked down an article from around this era to find out how they were making bricks then - this one was published in 1879 -

Aaron Broomhall tells us:

''The Brookvale Brickworks has a fascinating history dating back to around 1885, when William Hews established his brickworks at the corner of Bantry Bay Road and Warringah Road. The Hews family, the first permanent residents of Frenchs Forest, used high-quality kaolin clays to create bricks that helped build many of Manly’s earliest structures.

Brookvale Brickworks, later owned by the Austral Brick Company Limited in 1975, produced distinctive Brookvale Clinker Sandstock bricks until its closure in 1995. Clay and shale were sourced from Beacon Hill and transported on a miniature tramway to the brickworks.''

Warringah Shire Council records tell us:

''Hews bricks were hand made in moulds and fired in kilns for about 72 hours, using timber from the nearby bush. One man could make 12 to 13 hundred bricks a day! The bricks were transported by horse and dray to Manly, Narrabeen and The Spit, where they were loaded onto a punt and shipped to Mosman and the city.

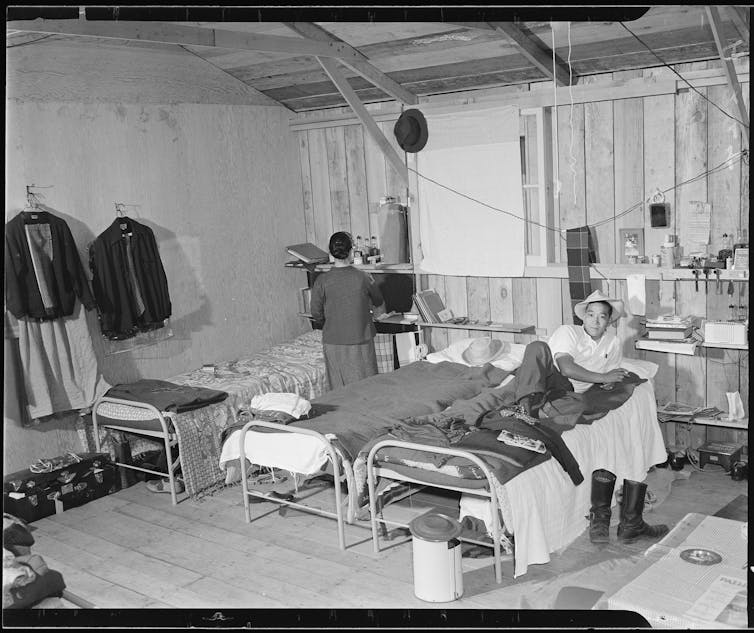

The workers were housed in small cottages, slab huts and dormitories. The Forest soon become a thriving community with the addition of a tennis court, cricket ground and pavilion.

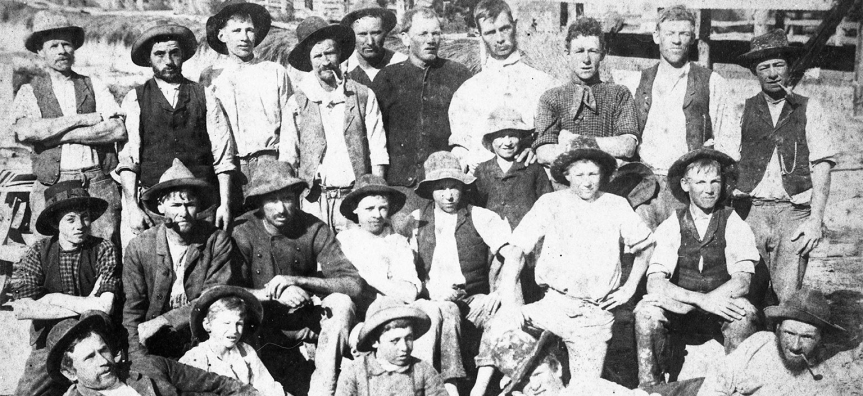

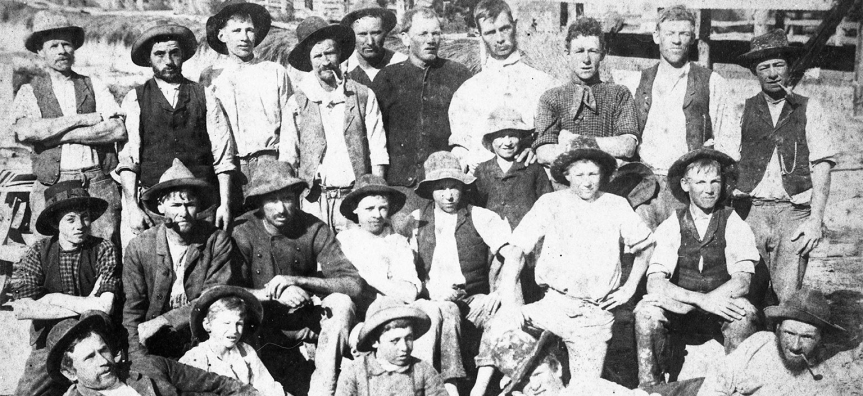

Workers at Brookvale Brickworks 1914

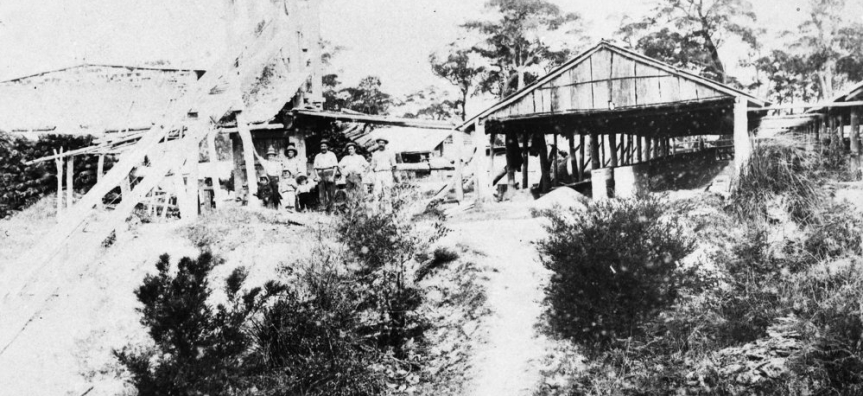

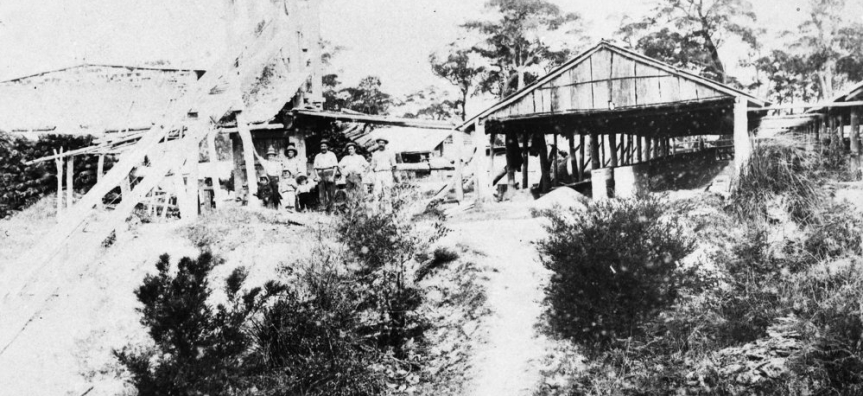

Hews Brickworks circa 1909

As the kilns consumed a huge amount of local timber, the brickworks impacted much of the surrounding bushland, already heavily logged by James French's sawmills. Hews Brickworks operated until World War I, when the essential clay was finally exhausted.

A small part of the Hews’ family land is now the site of Brick Pit Reserve with most occupied by the Northern Beaches Hospital. A plaque in the reserve honours the Aboriginal inhabitants and also commemorates the pioneers of Frenchs Forest.''

This tells us a run of 10 thousand bricks - and the makers mark - would have been around a week's work.

Mr. Hews was also a Warringah Shire Councillor - the first council chambers in Brookvale was built from his bricks, as were many of the homes in Manly.

He passed away in 1917 and is at rest i Manly Cemetery but Brookvale Bricks continued.

Four other locals who recall the works tell us:

''The football fields at the top of Beacon Hill are still sometimes referred to as "the brick pits". (On the left opposite Macca's on Willandra Road).'' and;

''And when they lit the kiln, the noise would rumble along Alfred rd Narraweena.'' and;

''Hence Hews Parade in Belrose where the President hotel was.'' and;

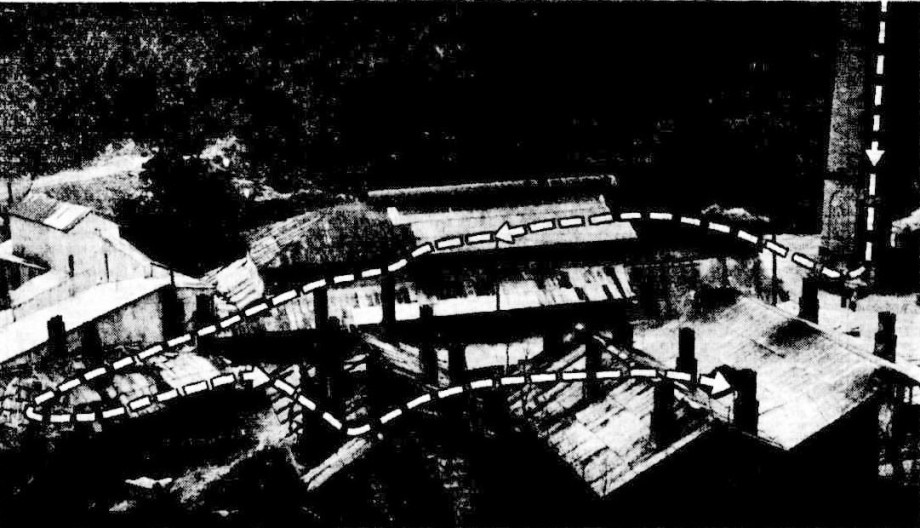

''Brookvale Brickworks and district has been photographed in this 1930 aerial. Includes the railway line from the clay quarry. Seems to show the railway passing underneath what is now Warringah Road. The Clay Tanks transported to the brickworks carried 4 tons of clay in each wagon. '':

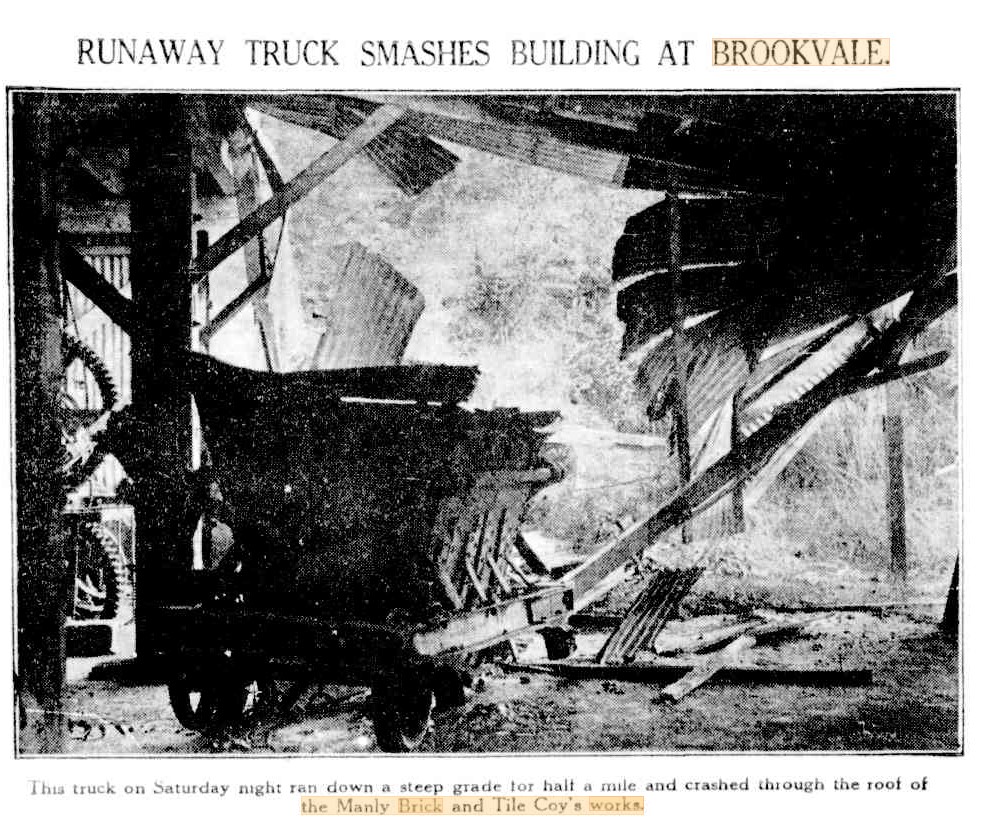

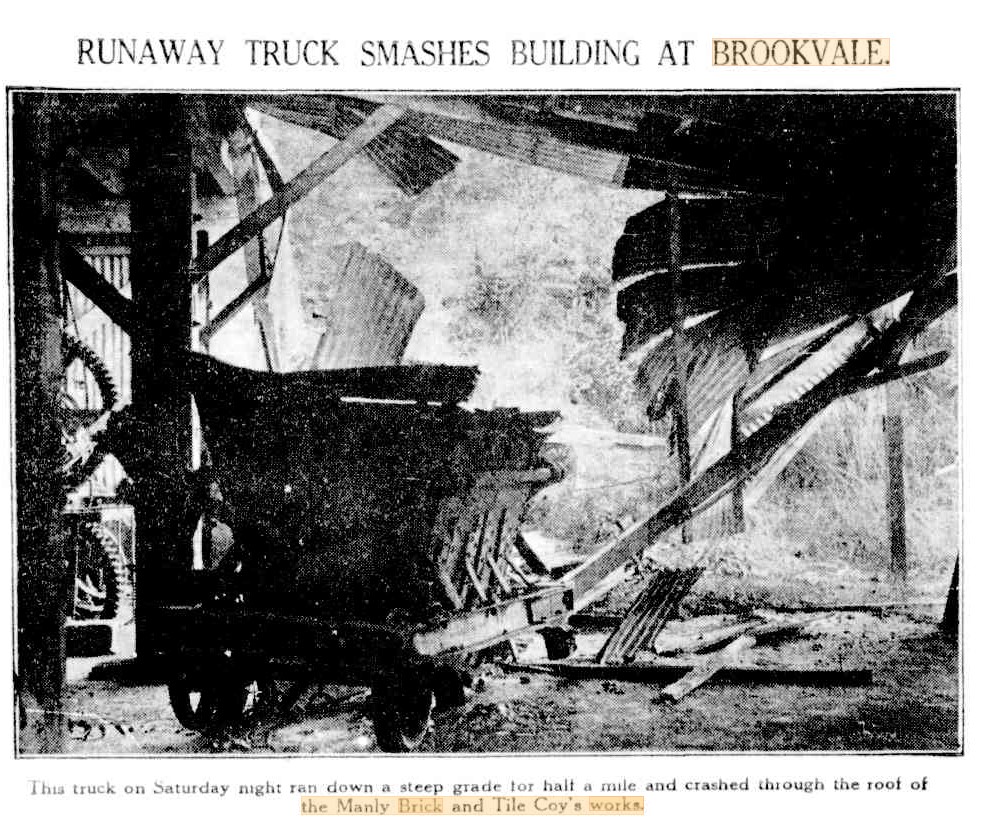

We also tracked down a few mentions from the newspapers of the past about this brick factory.

IN 1932:

BRICKS FALL ON WORKMEN.

Albert Kemsley, 47, of Hay-street, Collaroy, and Robert Riddle, 39, of Pittwater-road, Brookvale, had remarkable escapes from death or serious injury yesterday, when a stack of about 3000 bricks fell about them at the Brookvale Brickworks. The men were half buried in the bricks and were struck by many of them, but they suffered only cuts and abrasions. The Manly Ambulance took them to Manly Hospital.CASUALTIES. (1934, September 25). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 10. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article17115213

NRS-4481-3-[7/16056]-St21365. Title; Government Printing Office 1 - 26927 - Mixing Plant: Warringah Road, Frenchs Forest [From NSW Government Printer series - Man Roads]. Contents Date Range; 01-01-1938 to 31-12-1938, courtesy NSW Records and Archives

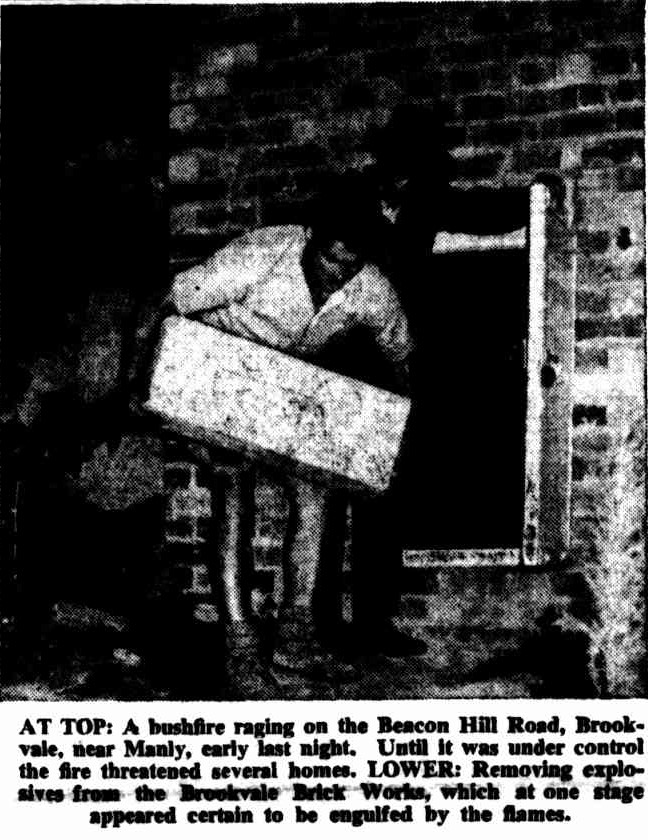

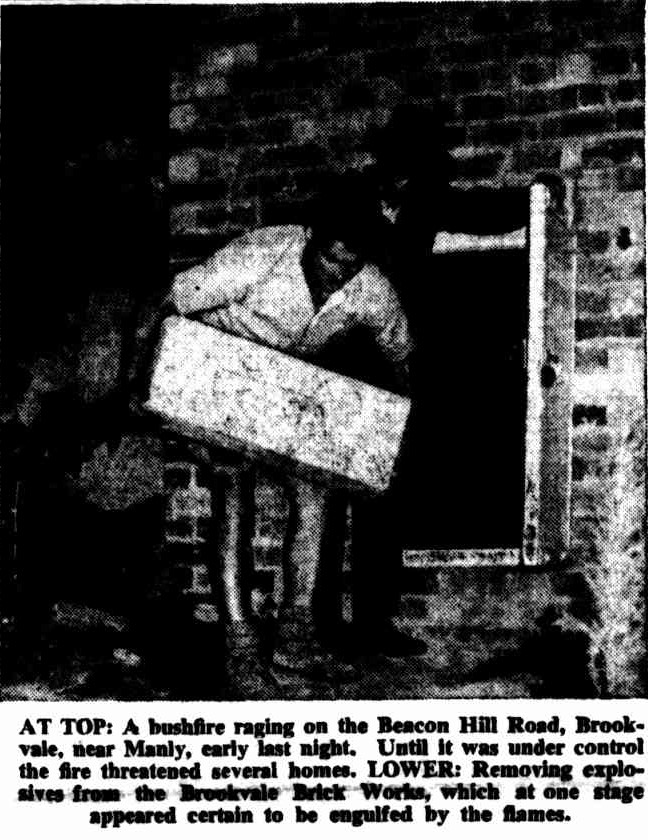

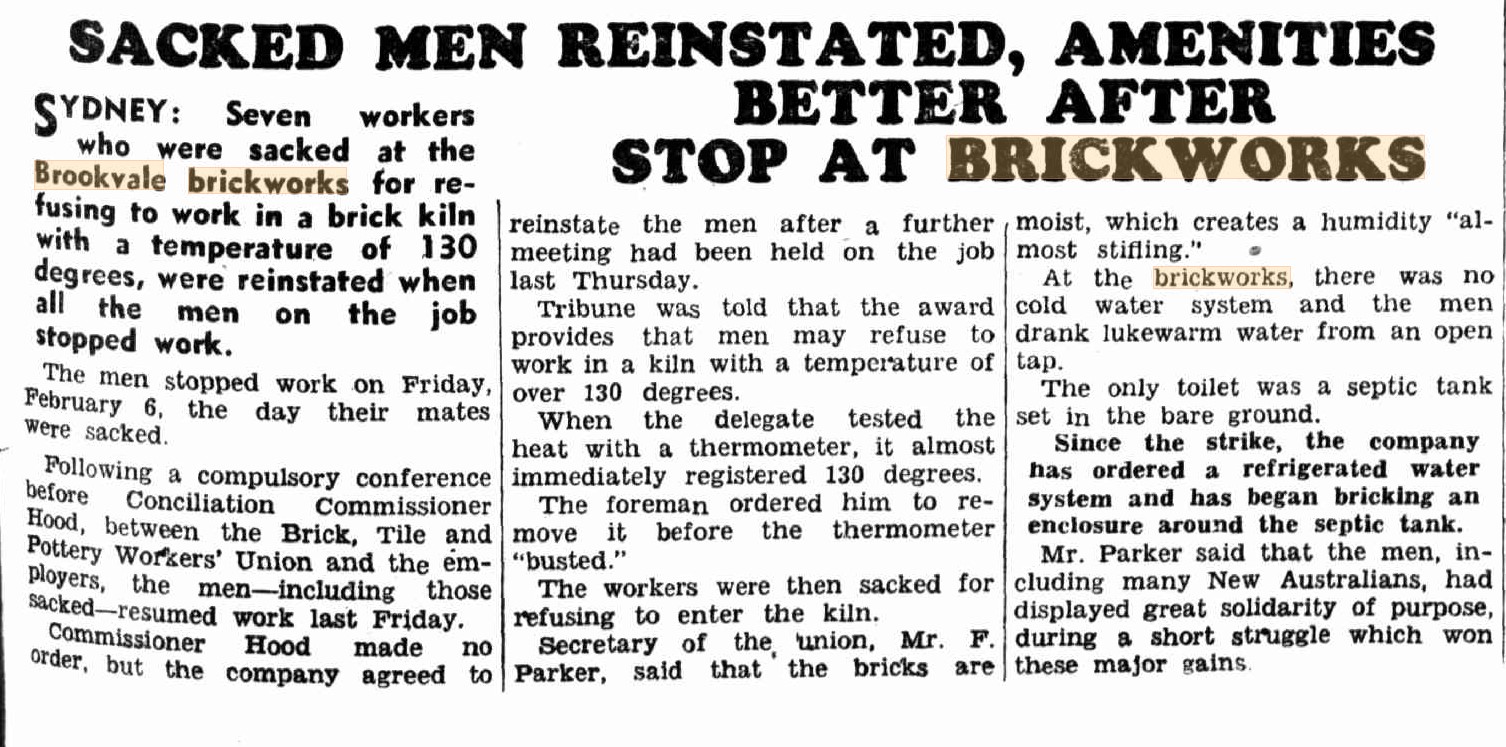

Fire in 1947:

Fireball a few years later:

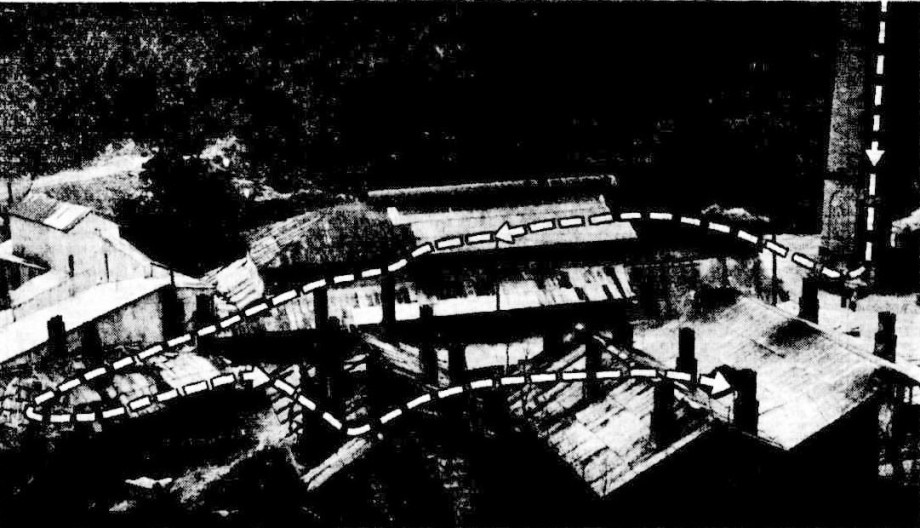

BROOKVALE BRICKWORKS DAMAGED BY FIREBALL. This picture shows the path of a fireball which severely damaged a brickworks at Brookvale yesterday. ' (Story page' 3.) BROOKVALE BRICKWORKS DAMAGED BY FIREBALL. (1952, August 14). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 1. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article18277490

At Brookvale a fireball struck a brickworks chimney at 6.10 a.m., and partly wrecked four brick kilns. Striking with a series of bomb-like blasts, it demolished a wooden structure 200feet square and hurled sheets of iron from it up to 200yards away. The works, in Federal Parade, Brookvale, are owned by Brickworks Ltd., Castlereagh Street, city. Only one man, Bill Bass, of Sydenham Road, Brook-vale, was on duty at the time. He was working in the first kiln. Bass jumped under a work-bench as bricks and sheets of iron fell around him. Scores of people in the Brookvale area reported seeing a flash in the sky. A spokesman for the company said last night that at least £3,000 worth of damage had been done to the kilns. They would be out of production for about a week. Willy-willy Rips Tiles And Iron From House Roofs. (1952, August 14). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 3. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article18277544

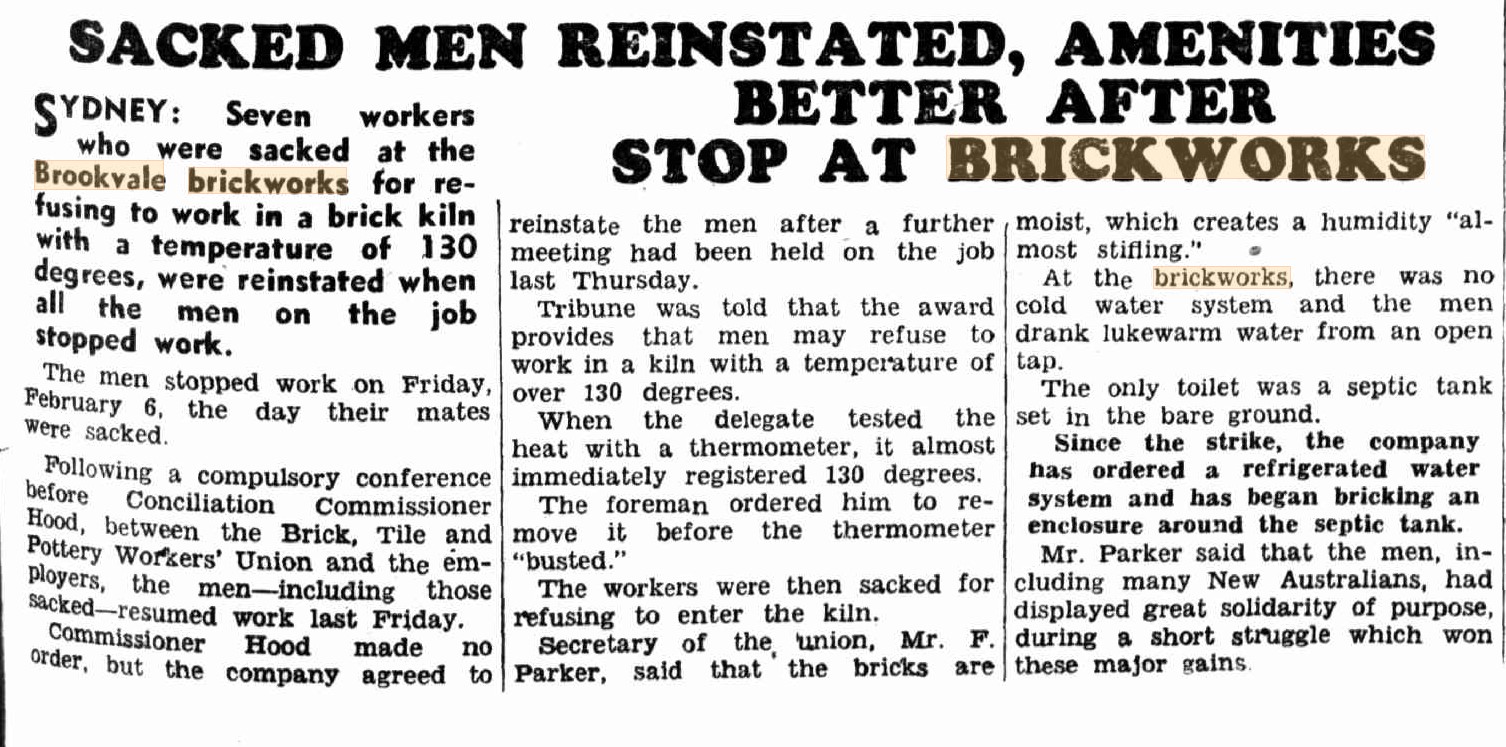

In 1959:

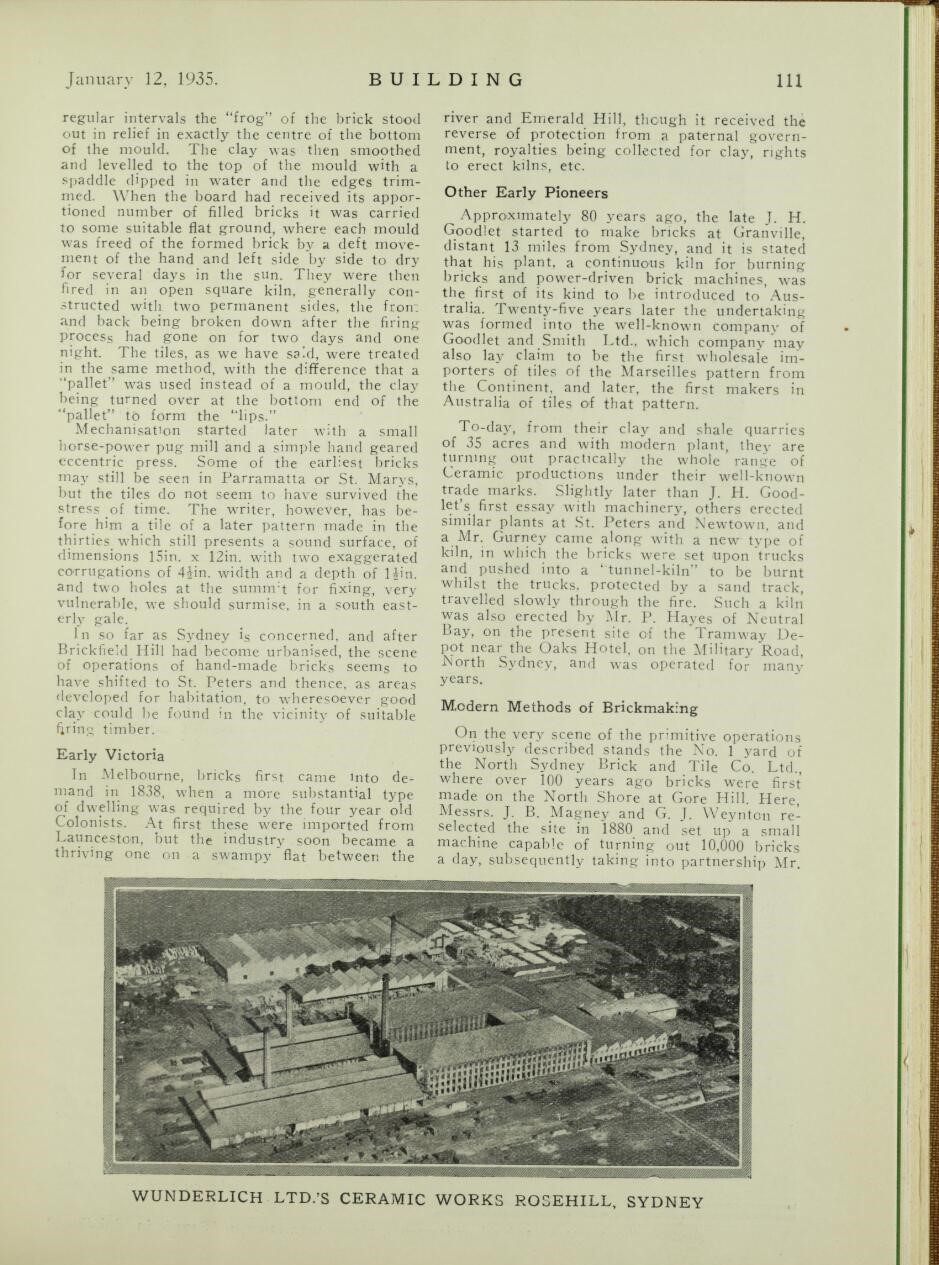

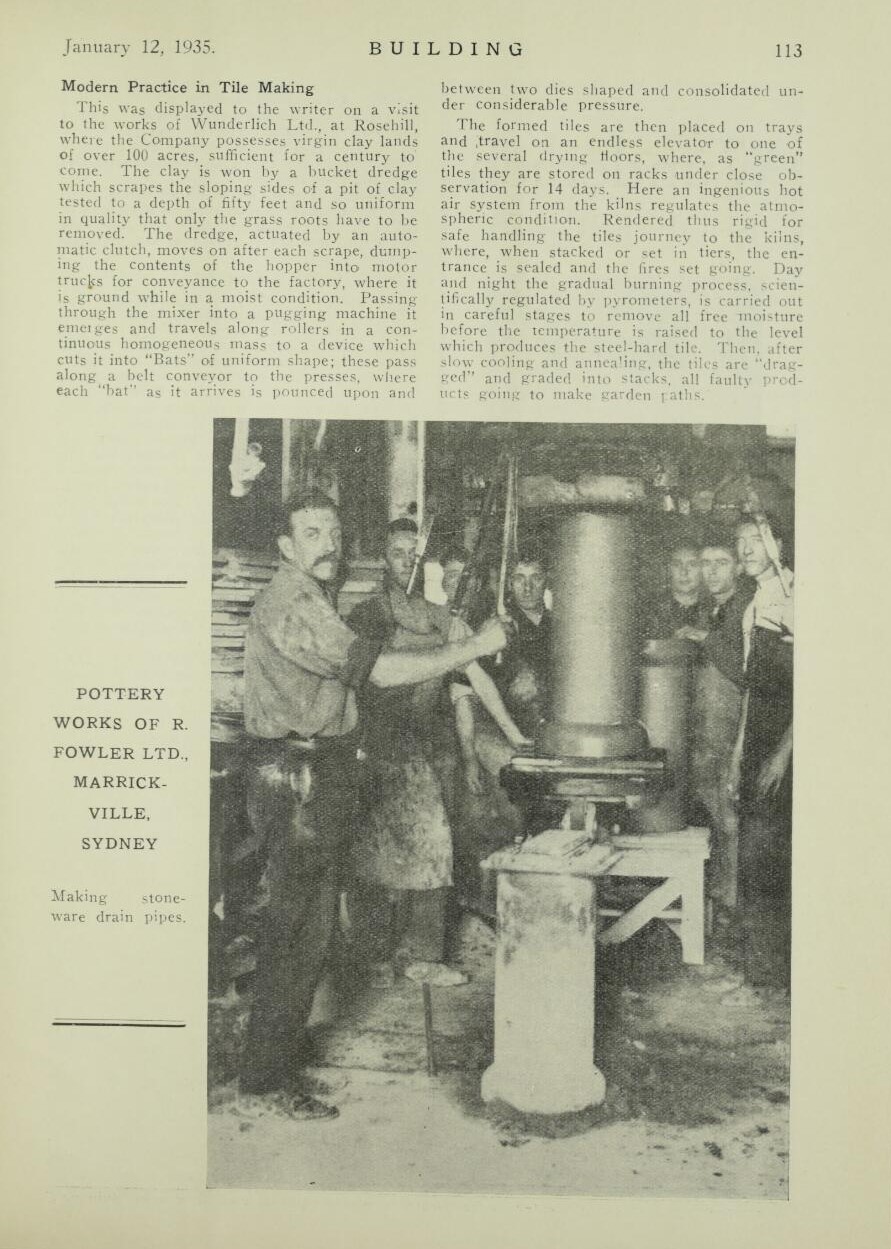

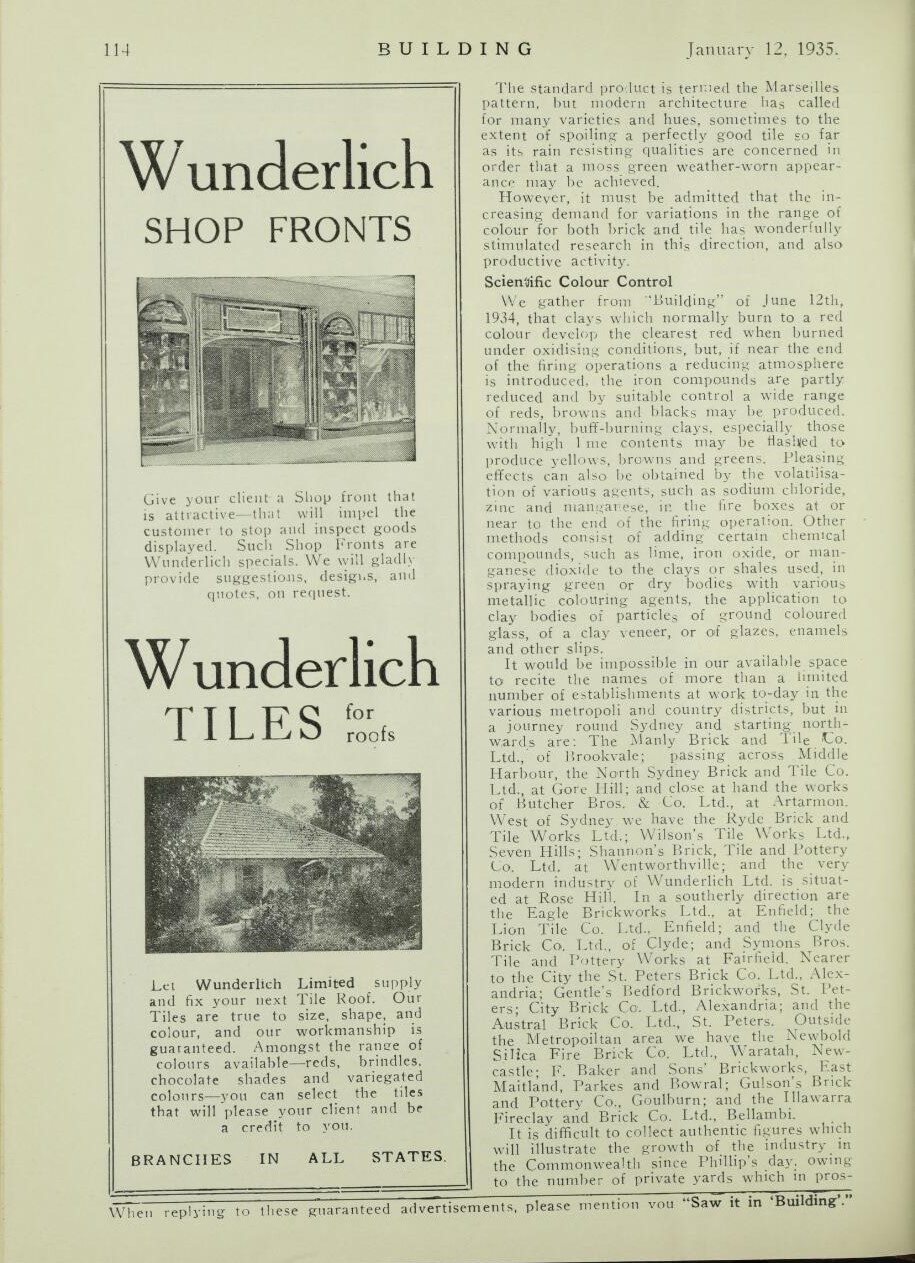

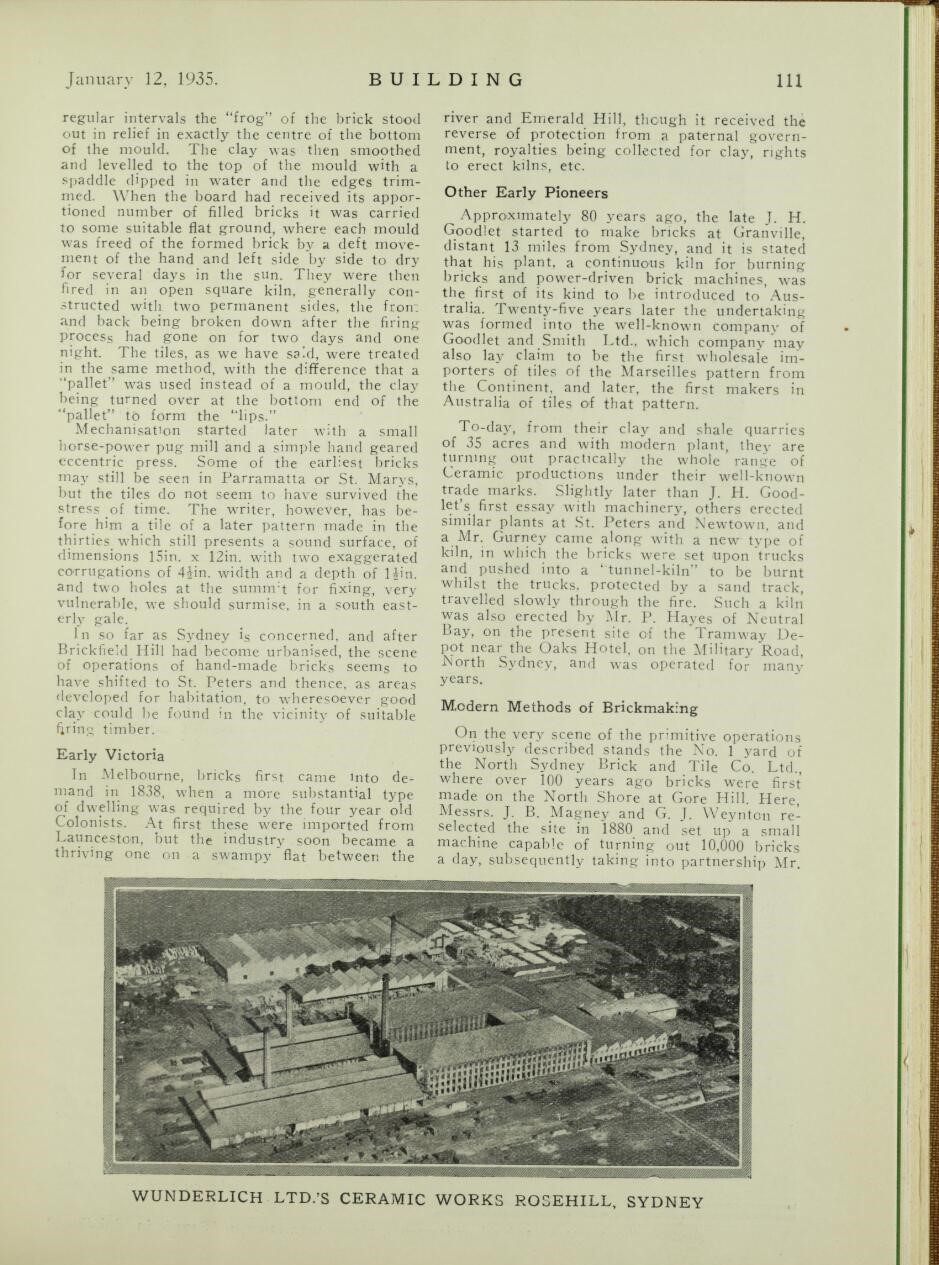

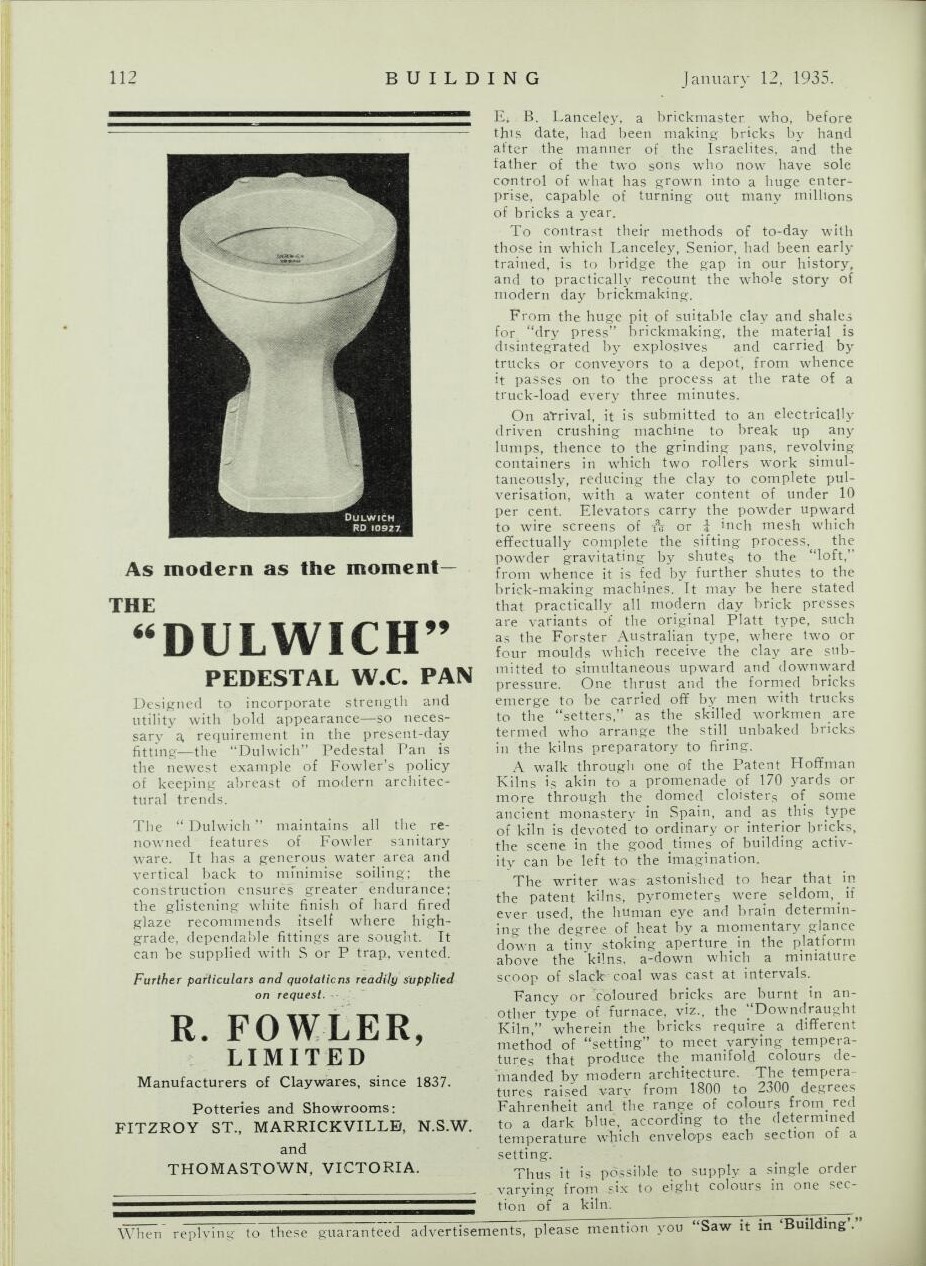

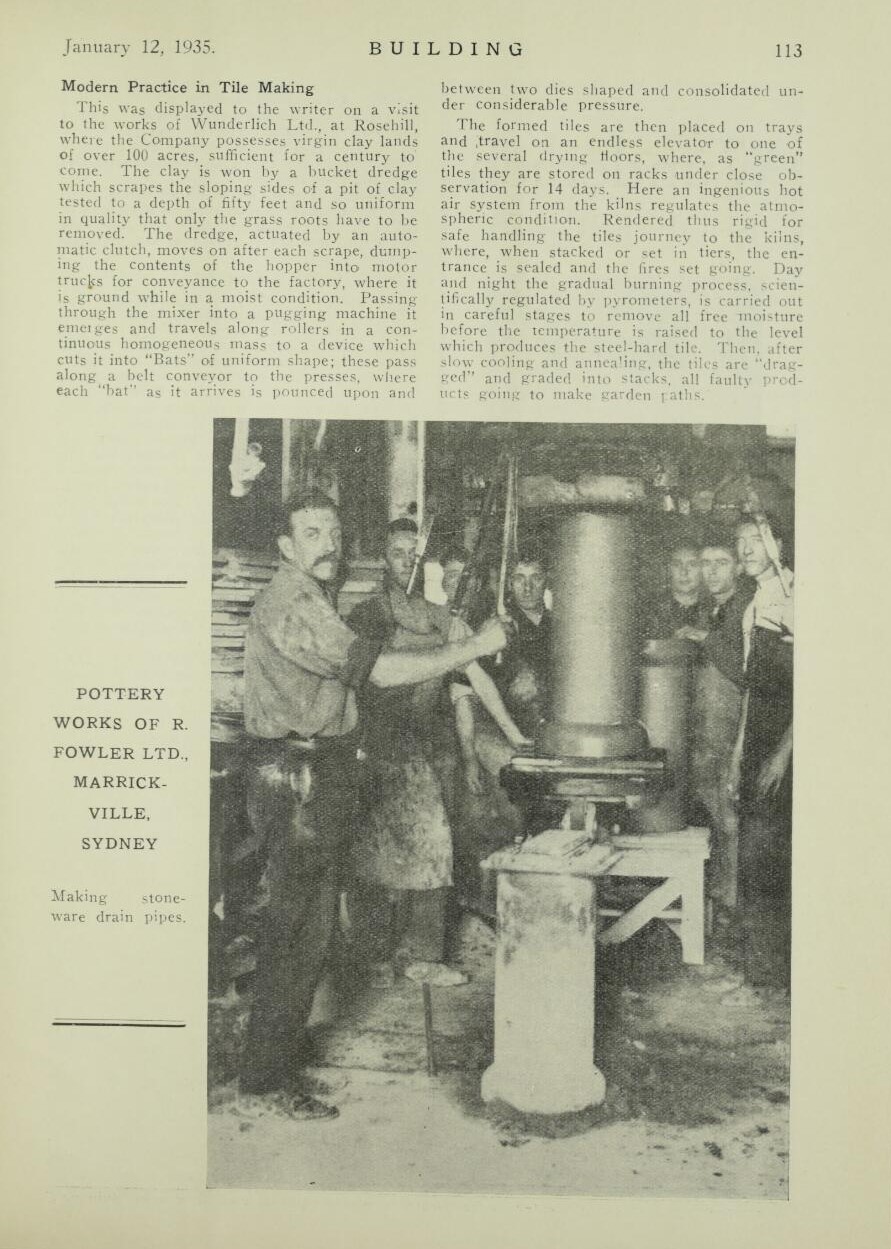

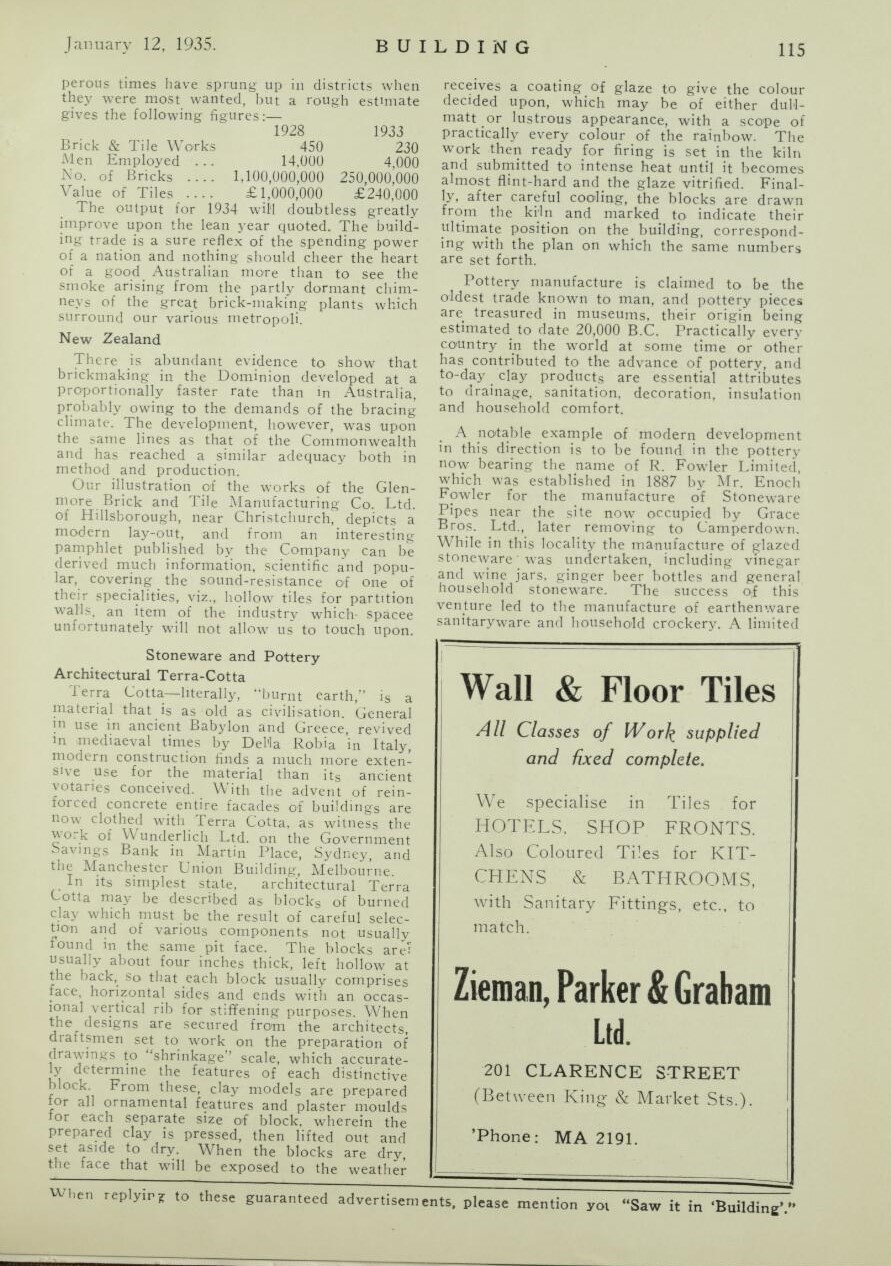

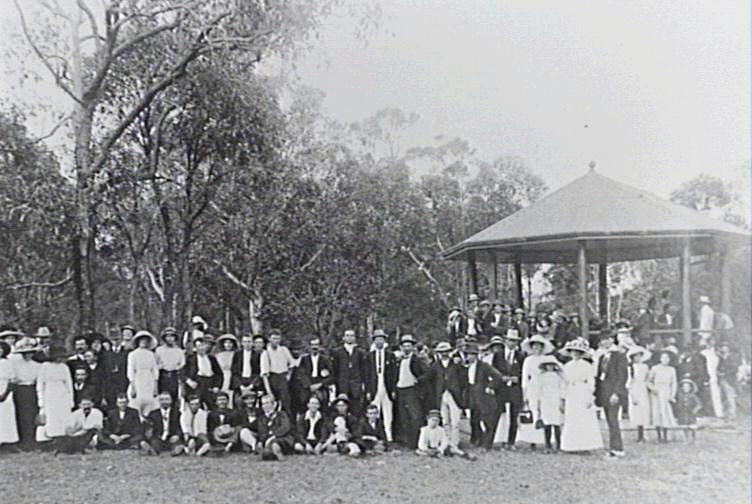

We also tracked down a bit of a history of brickmaking in Sydney, as run here in the Australian journal 'Building' in 1935:

This one form 1959 records fossils being found at the Brookvale/Beacon Hill brickpits - see right hand column:

Brookvale Brickworks circa 1950.Photo: Aaron Broomhall - and looks like a Warringah Shire Council one too

Rock Lily Hotel of Leon Houreux - built from locally made bricks from album, Box 14: Royal Australian Historical Society : photonegatives, ca. 1900, courtesy state Library of NSW

The Brock Estate - brochure Front page, 1907 Item No.: c046820078, Mona Vale Subdivisions, Courtesy State Library of NSW

James Baker's Mona Vale Food Store circa 1910-1912 - on today's Pittwater road heading out to Bayview, was made from local bricks - they sold it in 1919:

MONA VALE-PITTWATER Old established General Store and Freehold, JUNCTION STORE, Pittwater and Newport roads Modern brick building, large shop, 5 rooms, stabling, etc TORRENS. Raine and Horne auctioneers. Advertising (1919, March 6). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 10. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article15828225

References

- Pittwater Restaurants You Could Stay At The Rock Lily Hotel – Mona Vale (2021 updated version) - 2015 version

- John W. Stone - Profile (photographer)

- Pittwater Roads II: Where the Streets have Your Name - Bayview

- Roads In Pittwater: The Bay View road (becomes Pittwater road in 1950's)

- McCarr's Creek to Church Point to Bayview Waterfront Path - a 2018 longer stroll

- The Riddles of The Spit and Church Point: Sailors, Rowers, Builders

- The Oaks - La Corniche

- Guy and Joan Jennings, Mona Vale Stories. Arcadia Publishing, Newport NSW, 2007.

- Taramatta-Turrimetta-Turimetta Park, Mona Vale - officially opened in 1904

- Pittwater Roads II: Where The Streets Have Your Name - Mona Vale, Bongin Bongin, Turimetta and Rock Lily

- Early Mona Vale Constable owned Mona Vale Hotel site: some history

- Section Of A Squire Mural From Dungarvon, Mona Vale, held In Private Collection + a few notes about his focus on in situ Aboriginal Sculptures & local burial grounds of First Nations Peoples

- Pittwater High School Alumni 1963 To 1973 Reunion For 2023: A Historic 60 Years Celebration + Some History

- St. John's Anglican Church Mona Vale- Celebrating Its 150th Year In 2021 (History insights)

- NSW Records and Archives

- TROVE - National Library of Australia

- Pittwater Council, Mona Vale Library History Unit

Glenroy

George Johnson was born at the family house of 1891 Pittwater Road. His grandfather, Mr Arter, was a Lithgow businessman who came to live in the house near Waterview Street in the early-1890s with his family . Georges mother Mary had looked after the house and heryounger siblings when her mother passed away.

Mr Arter had built three cottages in the area of Bayview Road (now Pittwater Road) which were named Esbank, Lithgow and Bowenfields. After the three cottages were built Mr Arter continued to work as a bricklayer in the district working on the Rock Lily as well as Austin's

Stone.

On the other side of the family George's paternal grandfather married Louisa Oliver of the pioneering Pittwater family. George recalls how he and his brother would leave Mona Vale at 4.00am and walk behind their grandfather's horse and cart which carried wood for the bakery's oven or building materials for building at Manly. After lunch of half a loaf of bread and cheese each, the boys would ride the cart back home with the groceries.

When George was 4 years old he attended Mona Vale Public School, which was held in a cottage in Park Street. He was six when the school moved to it's new building in 1912 and he recalled a fire in 1918 in which the school had to temporarily locate to La Corniche while the school was being repaired.

George's father, George E. worked as a labourer in the Mona Vale area and is also named as a carter in the Sands directory between 1926 and 1933. On his property in Pittwater Road he also grew flowers which he sold to the local florist at Manly Wharf. He was the first

labourer on the Maintenance Department of the Warringah Shire Council. As the shire extended as far as St. Ives, he would travel there by sulky and camped overnight filling the potholes in the dirt road with a shovel and a wheelbarrow. He also cut the sandstone that was used by James Booth to build St. John's Church at 1624 Pittwater Road. The 'Glenroy' house is opposite St. Johns Church on Pittwater Road. - Pittwater Council Mona Vale Heritage Inventory, Study Number B71 - 16/07/2014.

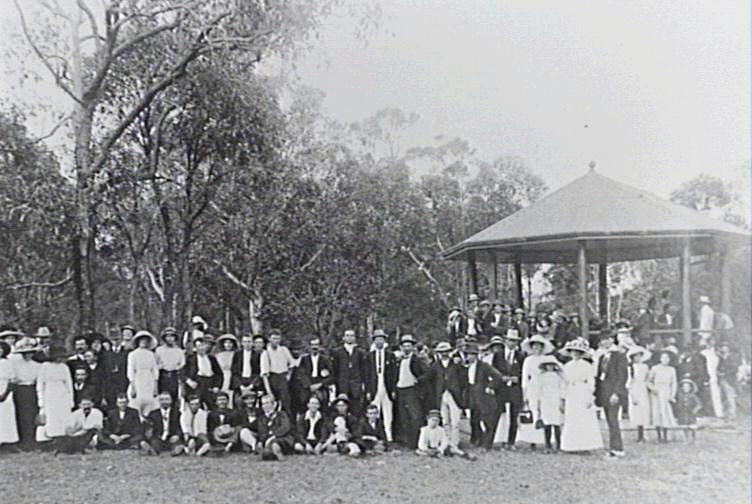

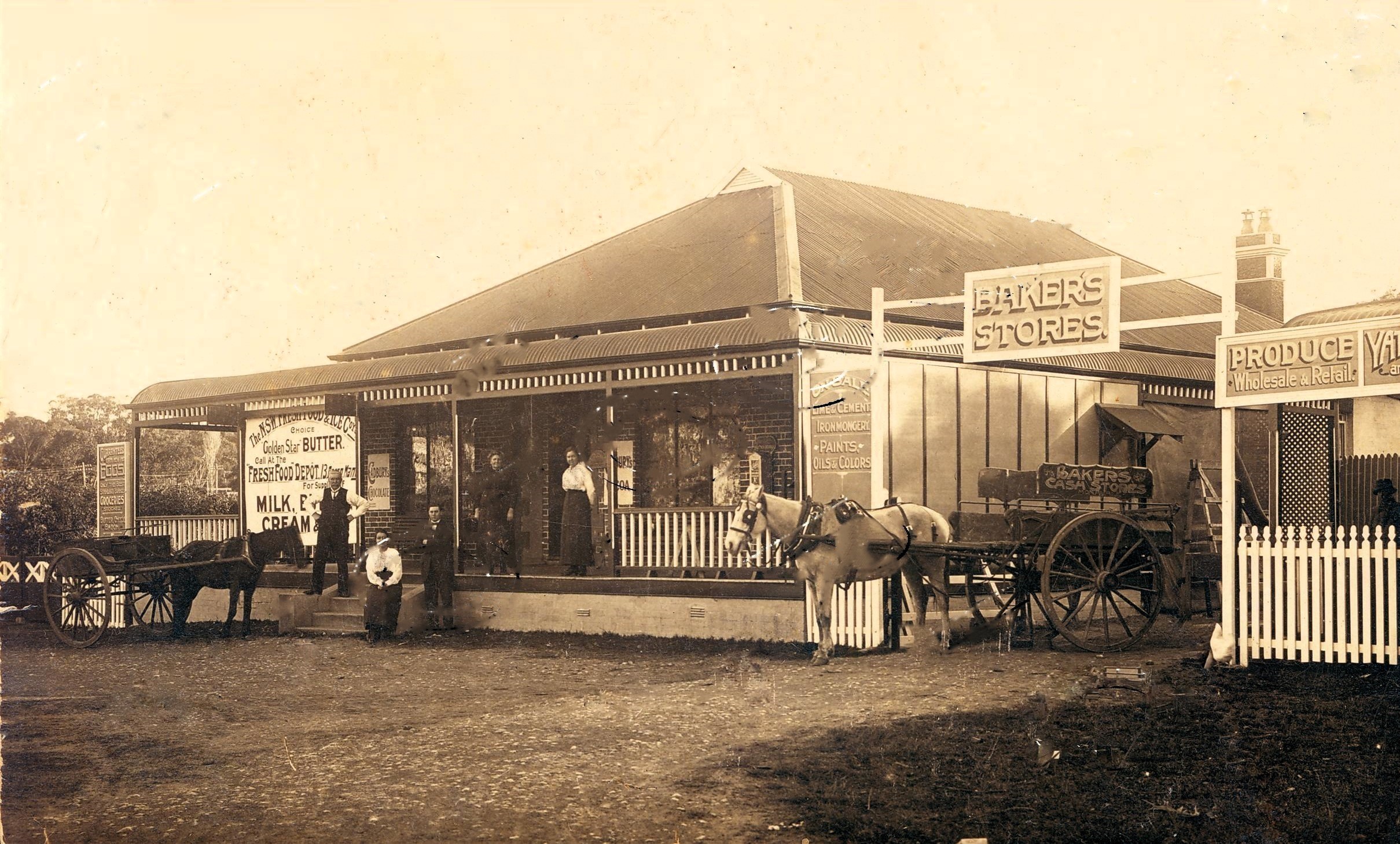

School Sports day at Kitchener Park, 1912 - photos courtesy Olga Johnson.

Information Provided As Mrs. Hawkins Talked With Mr. George Johnson, for Mona Vale St. John's Church records

31.7.78 (Pittwater High School)

Mr. Johnson was born at 1891 Pittwater Rd., in 1907. His grandfather Mr. Arter, who built houses A, B and C lived with Mr. Johnson’s parents and the rest of the family, at that address. Mr. Arter continued to work as a bricklayer in the district, working on the Rock Lily and the general store, at the site of the present paper shop. (Mr. Johnson has a picture or the two storied building.)

Mona Vale circa 1905 - looking towards Bayview. Mona Street runs off to the bottom right of this picture. To the left is St John's Church of England which was moved from Mona Vale headland, where it had been installed on the Boulton's Farm

Mr. Arter was a Lithgow businessman who came to live near the corner of Waterview St., Mona Vale, with his family. Mary Arter (Mr. Johnson’s mother had looked after her younger brothers and sisters from the age of 12 or 14, after their mother died. Mr. Johnson showed me his parent’s marriage certificate, showing the date of marriage 26/8/1903, and Mary’s age as 21 years. Mr. Johnson believes houses A, B, C were built prior to Mary’s marriage. Mrs. F. Lewis told Mr. & Mrs. Johnson that Mary said she was 17 when House A was built. Mr. Johnson recalls the bricks for the houses were obtained from Wilcox in Bassett St. area, and later from Mona Vale Rd.

Mr. Johnson’s paternal grandfather, who married Louisa Oliver, built the first house at Church Point. This house has been restored and re-decorated. Mr. Johnson has a photo of his grandfather, and he recalls how he and his brother would leave Mona Vale at 4.00am and run or walk behind grandfather’s horse and cart, as it carried wood for baker’s ovens or for building at Manly. After lunch of half a loaf of bread each with cheese, the boys enjoyed the cart ride back as groceries were carried back.

Mr. Johnson’s mother’s sister was married to Mr. John Oliver who, in an affidavit, described how residents flocked to the wharves when the steamers arrived and unloaded their supplies. The steamer carrying the tin used in the roof of houses A,B,C, would have been unloaded at the Bayview wharf, alongside the present William’s Marine. Mr. Johnson remembers the steamer’s whistle alerted everyone to the approach of the steamers. Mr. John Oliver worked for Mr. Geddes and mentions the ships “Hawkesbury”, “Narara” and “Erringhi”. Mr. Oliver was concerned to maintain the cemetery at Church Point- site of the Methodist Church.

John Oliver lived in the timber cottage at 1624 Pittwater Rd. after his father George. John later built where the Vet is now located.

Mr. Johnson’s father worked as a labourer in the Mona Vale area. On his property along Pittwater Rd. he grew flowers which he sold to the florist at Manly Wharf. He was the first labourer on the Maintenance Dept. of Warringah Shire Council. As the Shire extended to St. Ives, he would ‘travel to St. Ives by sulky, and camp overnight to enable him to maintain the road by filling in the holes in the dirt road, using a shovel and wheelbarrow. Mr. Johnson’s father cut the stone for the building of St. John’s Church at 1624 Pittwater Rd. There are two headstones in the churchyard, originally from the cemetery of the first St. John’s Pittwater on the Mona Vale headland off Grandview Pde. (1871-1888).

(Mr Geddes owned property on “Brick Yard Hill” ½ mile from Wharf, east towards Bayview).

Mr. Johnson has a postcard (as above), dated 1906, showing Pittwater Rd., Mona Vale with the three brick houses on the right, two houses and a wooden Church on the left of the road. Two of the brick houses were named “Esbank” and “Lithgow” (“Bowenfels” may have been the name of the third.) The two wooden houses were occupied by Wilsons and Aldridges. He cannot recall the occupant of the third wooden house. There are two tall cabbage tree palms on either side of the road, opposite house A.

There is a line or telegraph poles on the left-hand side of the road. Mr. Shaw built boats and launched them at the nearby creek. The black berry patch at the right of the picture, is the spot where the girl Godbolt was bitten by a snake, and ran home to near Loquat Valley School. Her mother treated her and she was away from school for four days. As a boy, Mr. Johnson’s Sunday Sport was killing black snakes with a stick in the swamp where the Bayview golf links are now located.

When four years old, Mr. Johnson attended the Mona Vale public School in the old house which still stands next to the lane off Park St. Mr. Morrison was the teacher. When he was Six, Mr. Morrison was the first teacher in the stone Mona Vale School. After the School burnt down, classes moved to La Corniche, with a new teacher and his wife. Mr. Ross and Miss Giddely were teachers when Mona Vale School was rebuilt. The house with the attic at 28 Park St. was built by Mr. Stringer, possibly at the same time as Brock’s was built. (later known as La Corniche).

As a boy, Mr. Johnson and his father used to do odd labouring jobs for Mr. Arter. Mr. Johnson believes Mr. Arter built the Bakery at the same time as the house. There was one baker before Andrieson. When Mr. Johnson was about 14, he worked for Mr. Andrieson, and recalls that young Jack Andrieson playfully tripped him as he ran from the Bakery to the house, with the result that he landed face down in his tray of hot buns. There was no license needed for making or selling bread in those days, but occasionally an inspector checked the weights of the bread. When 16, he worked for Mr. Maisey and he had a photo of himself with the bread cart, when the bakery was operating in Bungan St. Mr. F. Lewis recalls that Mrs. Shreinert Snr. used to serve teas in the side room at House b, before her son was married. The three houses were known as Show places in the district.

The Marshalls & Connelly were two families who lived along the present Mona St., north of Pittwater High School. Homers Dairy was located north of Bassett St.

In the early 1900’s Mr. Boulton was digging wells on a Newport property, and when he heard the lady owner wanted to sell, he said he’d found gold there. Coal shafts were dug uneventfully off Walters Rd. and also at Lane Cove Rd., Ingleside.

Mr. Johnson has an aerial photo -1906- of Bayview wharves, many of which no longer exist.

(The George Johnson’s lived opposite St John’s – George’s parents lived on the corner).

![]()

The powerful owl (Ninox strenua), a species of owl native to south-eastern and eastern Australia, is the largest owl on the continent. It is found in coastal areas and in the Great Dividing Range, rarely more than 200 km (120 mi) inland.

The powerful owl (Ninox strenua), a species of owl native to south-eastern and eastern Australia, is the largest owl on the continent. It is found in coastal areas and in the Great Dividing Range, rarely more than 200 km (120 mi) inland.

Biba was a London fashion store of the 1960s and 1970s. Biba was started and run by the Polish-born Barbara Hulanicki and her husband Stephen Fitz-Simon.

Biba was a London fashion store of the 1960s and 1970s. Biba was started and run by the Polish-born Barbara Hulanicki and her husband Stephen Fitz-Simon.

%20smaller.jpg?timestamp=1770841935247)

%20smaller.jpg?timestamp=1770841973640)

.jpg?timestamp=1770845756555)

.jpg?timestamp=1770845804830)

%20smaller.jpg?timestamp=1770340203705)

This is not the same as when plants are named after the people who ‘discovered’ them. This ‘naming’ is in English and is a person paying tribute to a grower of roses for example ‘Mrs Partridge’s blue rose’ or a ‘Granny Smith’ which was named after a lady in Eastwood (now one of Sydney’s suburbs) called Maria Ann Smith who developed this yummy green apple by chance when a wild apple and a domestic one accidentally seeded a new apple. Every year now the granny smith apple is celebrated as the Granny Smith Festival and will be again this year on October 20th, 2013. See

This is not the same as when plants are named after the people who ‘discovered’ them. This ‘naming’ is in English and is a person paying tribute to a grower of roses for example ‘Mrs Partridge’s blue rose’ or a ‘Granny Smith’ which was named after a lady in Eastwood (now one of Sydney’s suburbs) called Maria Ann Smith who developed this yummy green apple by chance when a wild apple and a domestic one accidentally seeded a new apple. Every year now the granny smith apple is celebrated as the Granny Smith Festival and will be again this year on October 20th, 2013. See

crowns may help you to make up your own dance!

crowns may help you to make up your own dance!

.jpg?timestamp=1770318390540)

%20smaller.jpg?timestamp=1769645602951)

%20smaller.jpg?timestamp=1769645638078)

%20smaller.jpg?timestamp=1769645668722)

%20mumma%20smaller.jpg?timestamp=1769645238812)

%20smaller.jpg?timestamp=1769644965301)

.jpg?timestamp=1769645711165)

%20smaller.jpg?timestamp=1769645775148)

.jpg?timestamp=1769645809209)

.jpg?timestamp=1769645866040)

A former childcare worker has made an unlikely career shift to waterproofing, part of an army of TAFE NSW-trained waterproof technicians. They are helping to address the leading cause of building defects across the state.

A former childcare worker has made an unlikely career shift to waterproofing, part of an army of TAFE NSW-trained waterproof technicians. They are helping to address the leading cause of building defects across the state.