With almost all menswear bought off the rack or online today, the “shoddy dropper” has long passed into obscurity.

This 1920s slang term, used only in Australia and New Zealand, referred to roving sellers of cloth. Most shoddy droppers sold men’s suiting such as serges and tweeds. They walked city streets or went door-to-door in suburbs and towns.

Driven by a cost-of-living crisis that followed the first world war, shoddy dropping was eventually killed off by rising wages by the 1950s.

The practice underscores how readily fashion markets respond to economic factors such as supply, demand, inflation and wages.

‘Suit-length swindlers’

The most successful shoddy droppers were smooth talkers attractively dressed in made-to-measure three-piece suits.

They often went door-to-door, trying to convince would-be customers they could afford to dress like them. All a customer had to do was buy the shoddy dropper’s “high-quality” suit-lengths at a price they would be unable to find elsewhere.

Some shoddy droppers also claimed to have a special deal with a tailor that allowed buyers to have their suit tailor-made at a steal.

The term “shoddy dropping” played on the dual meaning of the word “shoddy”. The first was a noun referring to a cheap fabric made from a mix of new and recycled wool. The second was an adjective meaning “inferior or badly-made”.

Both meanings of shoddy were implicit in an article published in a rural New South Wales paper in 1913.

Though the writer did not use the term “shoddy dropping”, they warned readers against travelling “suit-length swindlers”, saying that

shoddy articles are frequently palmed off as good quality cloths by irresponsible men.

The number of shoddy droppers at any one time was probably tiny, but since they were off the books they are impossible to quantify.

Having said this, crime and news reports suggest the practice began around the start of the first world war.

Supply, demand, inflation and wages

Shoddy dropping surged in the the 1920s and 1940s, as prices soared due to war.

Working-class men’s desire for well-fitting suits was another factor. When Melbourne carters and factory workers gave evidence to the Australian Royal Commission on the Basic Wage in 1920, for example, they said most men they knew wore tailor-made suits to and from work.

This created financial stress; spiralling costs meant made-to-measure suits were hard to afford.

Fashion was another likely reason for the surges in shoddy dropping in the 1920s and 1940s.

The slimline jazz suit, which came into vogue in the early twenties, was just one example.

The jacket of this suit was single-breasted and slightly flared from the waist, while the trousers were narrow and short enough to expose silk-knit “jazz socks”.

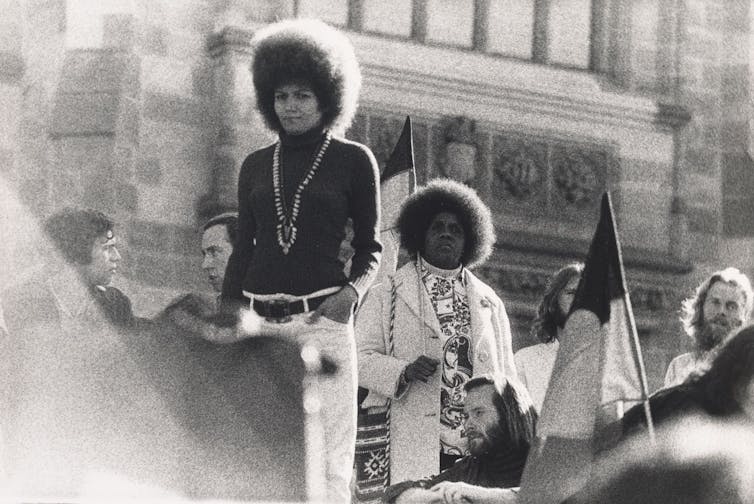

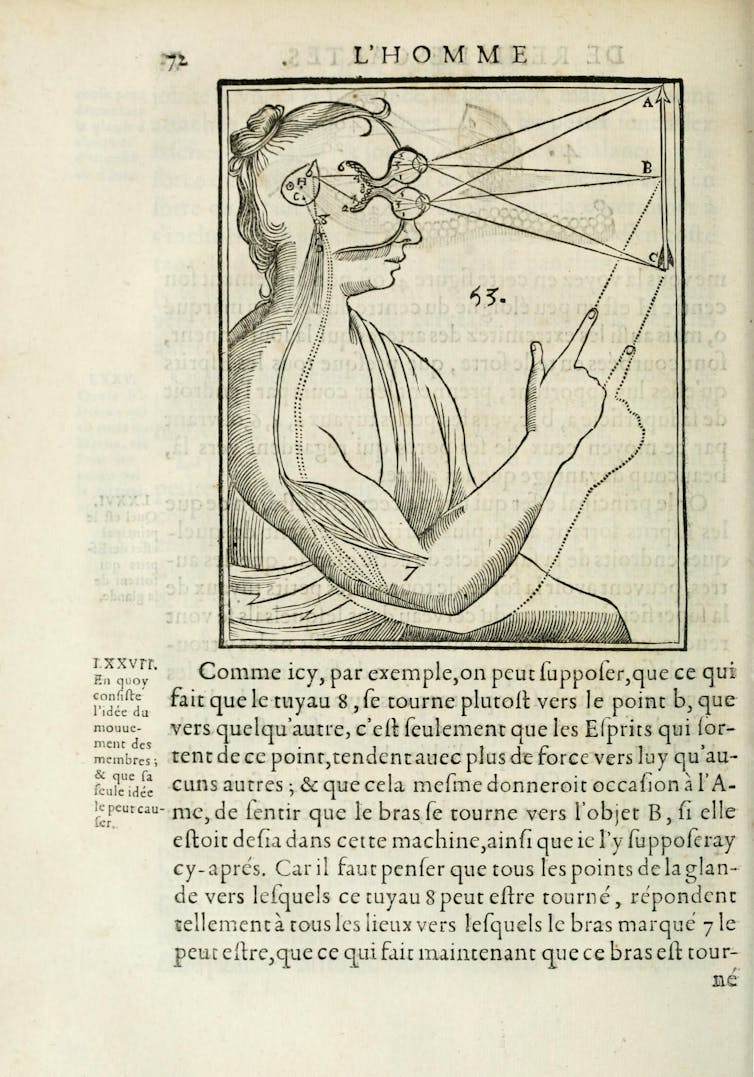

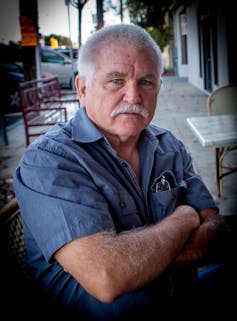

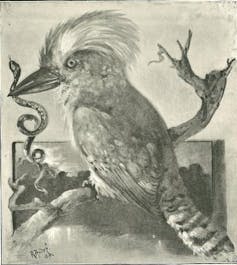

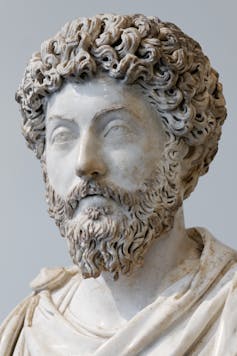

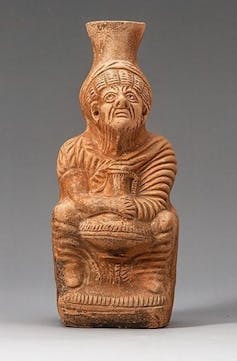

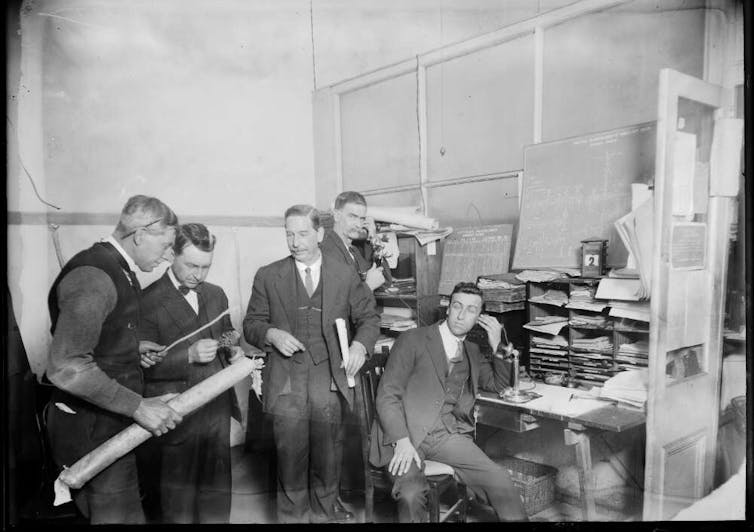

The impish charisma of the jazz-suited Louis Stirling below makes it is easy to imagine how a stylish shoddy dropper persuaded fashion-conscious young men to buy their wares.

Stirling was a suit-length seller photographed by Sydney police in 1920 after he was caught stealing cloth. He later produced evidence that he was a shoddy dropper to escape a vagrancy charge in Melbourne in 1922.

The high number of restless first world war veterans looking for work was a further reason for a surge in shoddy dropping in the 1920s.

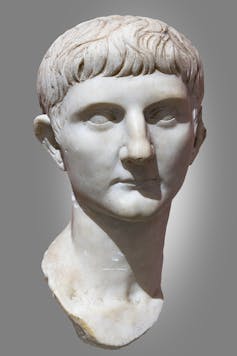

Consider returned serviceman Reginald Sharples (also known as Walter Johnson). In 1920, police charged him and an accomplice with stealing more than £1,000 of men’s suiting from a tailor in Sydney’s Hunter Street. This was somewhere in the vicinity of A$83,000 today.

Sharples was caught after transporting the stolen cloth to Melbourne. Like Stirling, he later produced convincing evidence to show that he was a shoddy dropper to escape a vagrancy charge.

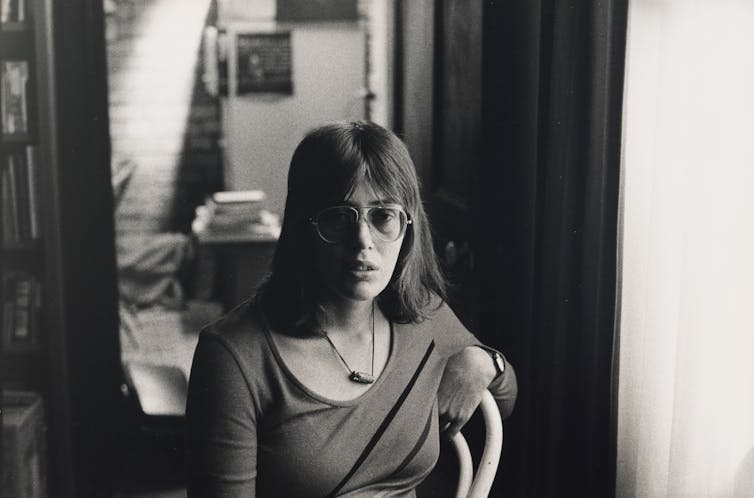

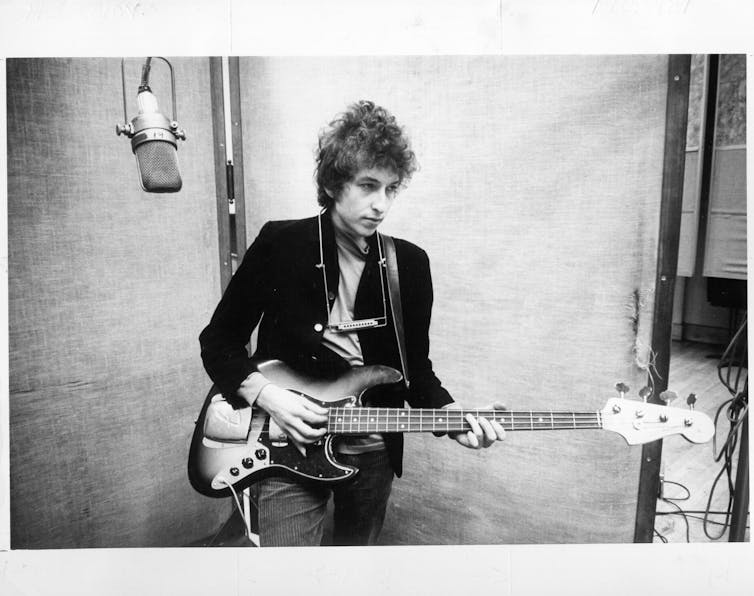

In his 1920 mugshot, Sharples is dressed in an early interwar version of smart-casual street style. He had combined a light pinstripe suit with a cream turtleneck sweater, black fedora and returned-serviceman’s badge.

Sharples was also an example of links between shoddy dropping and organised crime in and after the 1920s.

Apart from the suits-stealing charge, Sharples was also convicted of stealing morphine and cocaine from a wholesale druggist in Melbourne in 1922. He was also unsuccessfully prosecuted for vagrancy along with Louis Stirling in 1924.

Rumours that both men were associates of underworld figure Squizzy Taylor swirled in court during the trial.

A cost-of-living story

Shoddy dropping had disappeared by the mid-1950s, thanks to rising wages and increasing sophistication in the manufacture of ready-made suits.

These factors meant there were fewer low-income men who felt the only way they could afford a decent suit was to first buy cloth “off the back of a truck”, then face the uncertainty of arranging for it to be tailor-made.

Though shoddy dropping flew under the radar even in the 1920s, it is worth remembering today as a reminder of the unscrupulous selling practices that bloom in cost-of-living crises.

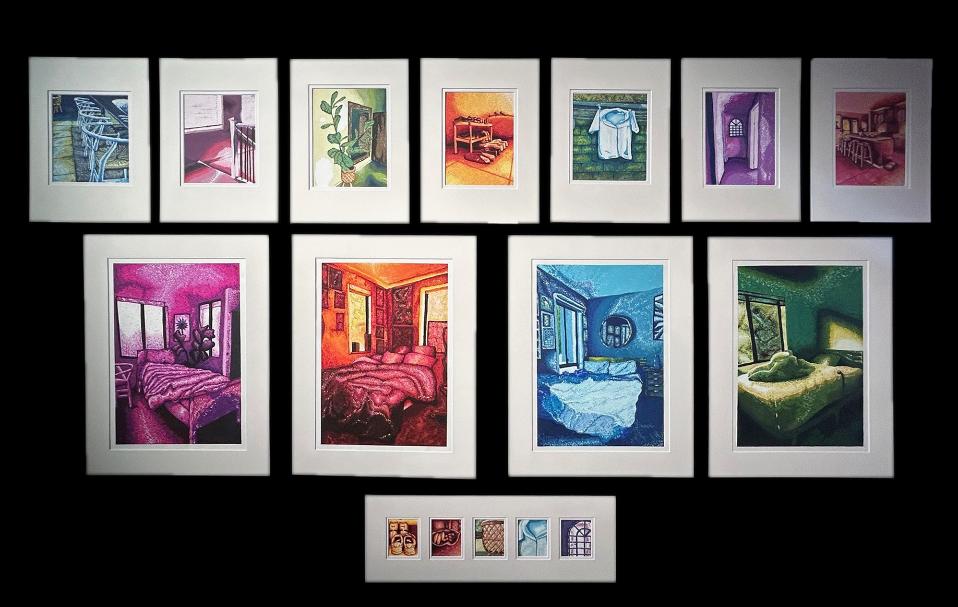

Along with the evidence in the extraordinary informal mugshots taken by Sydney police across the interwar era, shoddy dropping offers further insights into Australia’s history of male fashion consumers’ desire.

It has often been said Australian men were a cause lost to fashion. Shoddy dropping suggests that, in fact, many longed to dress in tailor-made suits and quality textiles. For many, however, those commodities were frustratingly out of reach.![]()

Melissa Bellanta, Professor of Modern History (Australian Catholic University), Visiting Professor of Australian Studies (Seoul National University), Australian Catholic University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

.jpg?timestamp=1737791672403)