December 4 - 10, 2022: Issue 565

St Michael's Cave - north avalon headland: Some history

The cave named ‘St. Michael’s’ has had many stories written about it through the century and a half or more since its discovery – including being once slated for use as a chapel or meeting place for worship. For many years it was one of the places to visit for people coming to Avalon.

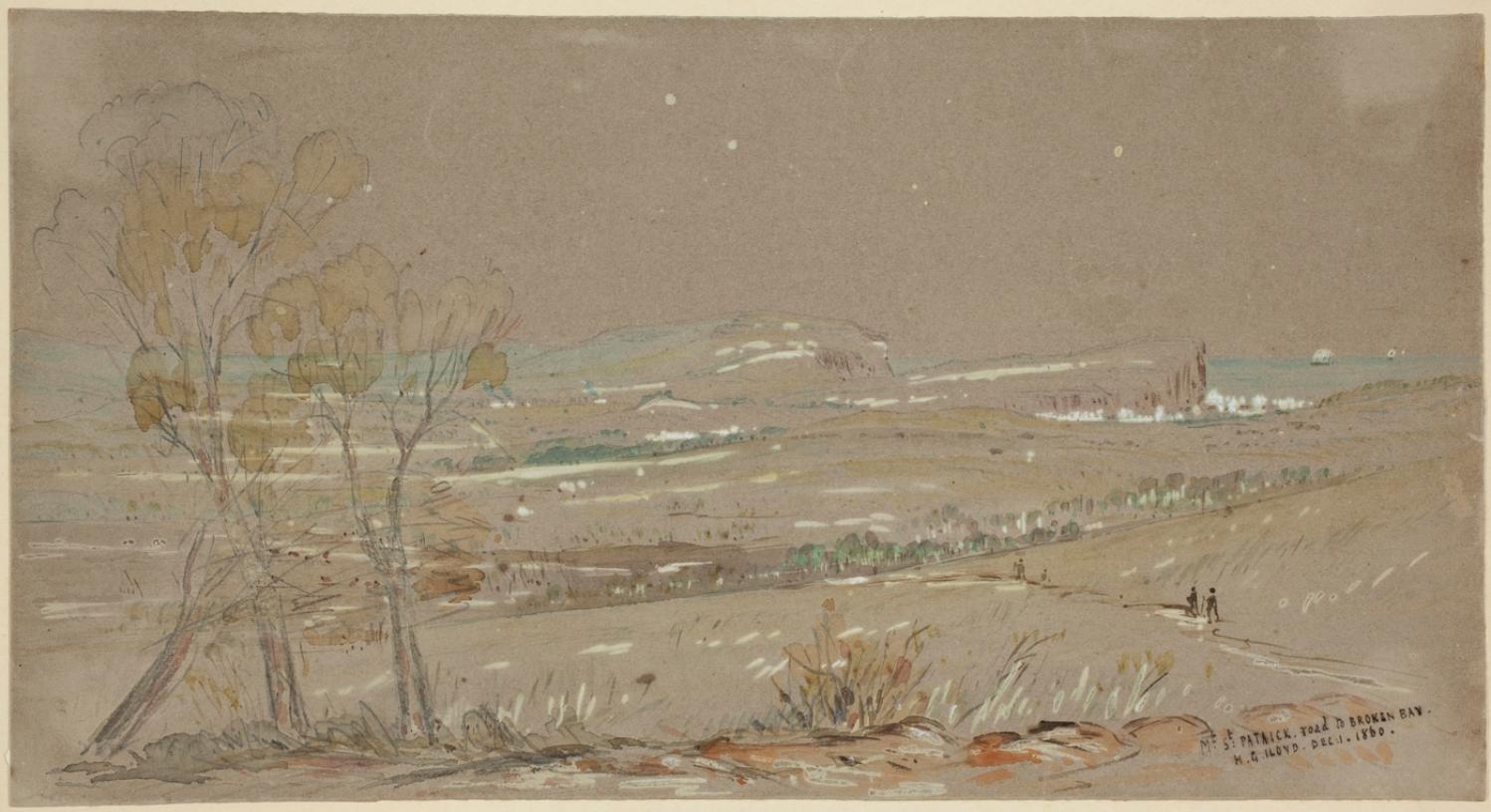

Every headland in Pittwater has unique silhouettes that make them identifiable, and the places they mark ensure a pilot, boat captain or walker who knows of them by sight will also then know where they are. To close our month of Pittwater landmarks we go east to North Avalon headland as its landscape has features still present and unusual landforms now gone or dangerous to access that encompass its land and seafronts.

Tucked closer to Bangalley headland then the northern point is St Michael’s Cave, now fenced off due to the landfalls within the cave and the cliffs above it that make it dangerous to visit. Residents need only recall the tragic accident that occurred on 21st of February 2004 on Bangalley Headland where a huge sandstone block two tourists were standing on slipped, crushing and killing one who fell with it instantly. The other was fortunate to fall backwards.

The cave’s name came from Archpriest Joseph Therry and was part of a land grant of 1833.

"in pursuance of a promise made by Sir Thomas Brisbane, and granted by Governor Bourke on the 31st August, 1833." (OBrien.1922. P.279) acreage was given to Father JJ Therry and By virtue of a promise made by Sir Richard Bourke in 1835 a further grant of 280 acres adjoining was made on 11 February, 1837. In 1836 he purchased from private owners 10 acres at the head of Narrabeen Lagoon. The land at Pittwater still bears the name of the "Priest's Flat." Here he placed Dr. Bergin, who superintended the cultivation of the land; and the foreshores produced shells, which were used for lime. Father Therry's nephew recalls how shiploads of shell were sent to Sydney, and there sold.

Father Therry planned to establish a chapel on the cliff above, although some sources state he intended to have a church within the cave itself and conduct Lectures and Services in the cave's room. In another stone structure on the rock shelf outside this large natural room, swept away in a storm in 1950(?) and called until then ‘The Pedestal’ he saw a natural pulpit. A little further south a stone archway, also washed away by storms, indicated to Therry, as it had long to our original custodians, the sacredness of this place. Photographed while 'treading this path' as part of the research is another unusual stone shaped alike an arched church window. (see left)

Numerous visits to this cave formed part of any excursion to ‘Pitt Water’ during this time;

PITT WATER.

Yesterday, being Easter Monday, a pleasant steam excursion took place in connection with the St Benedict's Young Men's Society. The commodious steamer the Collaroy, under the command of Captain Mulhall, had been chartered for the occasion, and left the Australasian Steam Navigation Company's Wharf, Sussex-street North, with about 260 persons on board, at ten o' clock a.m. Part of the band of H. M. S. 12th Regiment were in attendance, their cheerful and untiring efforts contributing not a little towards making the day pass harmoniously and agreeably away. Working along through the everchanging scenery displayed on the shores of our harbour, the Collaroy at length rounded the Heads, and, taking a northerly course, rushed past that enormous barrier presented by the weather-worn cliffs which face the ocean between the Great North Head and the seaward aspect of Manly Beach. Following on the interesting coast line of Curl Curl, Dee why, Long Reef, and Narrabeen, &c, - varied succession of wooded eminences, long sandy reaches, towering precipices, and grassy park-like slopes, - the pleasure-seekers were at length abreast of the singular headland of Barrenjoey, forming the extreme south-eastern limit of the estuary which serves as a common outlet for the River Hawkesbury and the Pitt Water. Shortly after passing the Custom House station the course of the Collaroy then took a southerly direction, and so brought the holiday folks into the lake-like solitudes of Pitt Water, until wooded hills seemed to be rising on every side of the vessel.

The passengers were landed at a small, but commodious wharf, erected on the property of the Venerable J. J Therry, under whose especial patronage the excursion had been got up. Most of the visitors set off in quest of St. Michael's Cave, determined not to lose the opportunity of seeing so great a natural curiosity. The walk, it was found, lay through woods, a long flat, and a hilly scrub, until, facing to the east at the head of the inlet, the merry party, in a straggling Indian file, at length arrived in the vicinity of the cave, cautiously descending the rocks, and creeping carefully along a narrow path specially made for their convenience on the face of the cliffs, they were thus finally rewarded for their perseverance. Almost every body managed to scramble up into the cave, and not a few of the more adventurous explored its inmost recesses by candle-light. The effect of the gloomy inner arch looked down upon from the top of the second angle of the cave, was much admired; and so also was the wider arch at the entrance, as contemplated from the spot where the bright daylight again began to stream down upon the faces of the returning explorers. There was, for some time, a pleasant buzz of conversation and a discussion of food at the mouth of St Michael's Cave, and then the party set out on their way back to the steamer, where dinner had been prepared.

Some with sharpened appetites posted thither at once, but many remained with the band near the house on the flat, and amused themselves with dancing, playing cricket, and so on. There was some dancing also at the steamer after dinner was over. The Kembla steamer visited the wharf at an early hour, landed some passengers, and afterwards returned for them. The Collaroy left the wharf for Sydney at about five o'clock, and arrived safe at Sydney soon after eight. The Right Worshipful the Mayor of Sydney, the Mayoress, and other members of the family were on board. We also observed the Rev. Fathers Corish, Curtis, Hanson, and Powell, besides the Venerable J. J. Therry. The trip appeared to give general satisfaction, although a slight shower, soon after the arrival of the Collaroy at Pitt Water, interfered with some of the arrangements.

PITT WATER. (1862, April 22). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 4. Retrieved December 6, 2011, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13227471

Earlier, Charles De Boos, in his serial 'My Holiday', also visited the cave, conducted there by a member of the Collins family who lived down on the flat area between current Avalon Beach and Careel Bay where they conducted a dairy:

Following the road, we mounted and crossed the range which terminates in the bluff headland, at the base of which I had been so completely drenched on the proceeding day, and then followed a gradually descending track which wound round the hill side into a deep indentation of the land, until it came down to the level of the sandy ridges which bordered the beach, and then dived into a thickly wooded dell, which though so close to the borders of the seam was one tangled mass of vegetation. It was in fact the embouchure of a long gulley, that, separating two extensive and lofty spurs from the main range was so far sheltered by each from the cutting breezes of ocean, as to allow of the growth of every description of plant in we same profusion as in the gullies I have previously described. Through the midst of it ran a tolerably broad sheet of water, the ordinary brooklet of clear, bright, and sparkling water having been transformed by the late rains into a miniature torrent, turgid and bellowing and carrying down before it small boughs and debris from the hills above, in humble imitation of larger streams. By the aid of a fallen tree we managed to cross the stream dry footed, but it was only by breaking down and walking over the branches of the bangolas and by taking advantage of such tufts of grass or such dead timber as offered that we could manage to cross the centre of the gully which the brook had covered with a mimic inundation.

Once through this jungle of a gully, and we had a gently rising road, creeping steadily up the face of the range, by easy graduation until at last it had gained the crest. Then we had a monotonous walk along the top of the ridge, in full view of the vast Pacific to our right, whose waves were now beating almost lazily along the beach at our feet and whose waters had barely swell enough on them to keel over the tiny fleet of coasters that had put out from different ports of shelter on the coast with the first slant of the favouring wind, and were now lying almost motionless, with scarce wind enough to lift their sails. To the left, the hills, covered with the low close scrub common to our coast ranges, bounded our view, the inland ridges, with their heavily timbered sides being hidden from our sight. Suddenly, however, the road took a curve round to the left, crossed a knoll of the range, and then swept down, in some fifty different tracks, on to a broad swampy plain, or flat, which seemed to us to be inundated, for we could see the water sparkling and glistening in the sun over its whole face. I pulled up short here.

" It won't do to go down there, Tom," said I.

"Oh, but we must," he replied. "This is the Priest's Flat, and there, where you see those shears erected, with the two tents alongside of them, is where they are boring for coal. We must go and report progress."

I looked ruefully at Nat, who made no reply, but, grinning viciously, bent down and turned up his trousers to the knees.

“Do you think there are any leeches there ?” I asked. Nat's trousers were instantly turned down again, and this time he didn't grin,

"Oh, no," Tom answered, "there's too much water there for them, and not enough shelter.

I was easier in my mind, though I had my misgivings; but as these Antipodean leeches seemed to be ruled by laws, and to have amongst themselves habits and customs totally at variance with those of leeches in civilised communities, possibly Tom might be correct; so, tucking up my trousers, I prepared to descend. And, after all, when we got down to the flat it was not so bad as it had appeared to us from the hill. The ground was somewhat honeycombed and the water lay in pools, between which however, we managed to find sufficient footing without actually walking in water.

Arrived at the tents, warning of our approach was given by a solitary dejected bark, ending in a melancholy and prolonged howl, from some unseen dog, that was evidently too broken down and low-spirited to repeat the challenge and it was only after we had approached the shears, and had commenced our examination of the boring, which, to tell truth, none of us could make head or tail of, that a tall sailor looking man, who appeared as if he had but just that instant been uncoiled full-rigged from between the blankets, came out to the entrance of one of the tents, and regarded us with an air of blank and sleepy astonishment. Just after him followed his watchful canine guardian, whose short bark and long ululation had effected his master's awakening, but so far behind as not to be within kicking distance; his cowering watchful look, and his tail hard down between his legs, evidently saying as plain as could be said, " I don't know whether I have done right, so I must stand by for squalls."

It took a good deal to waken up our friend to a full sense of the information we required from him, and it was only by the casual mention of Farrell's name that he was brought to his full mental perceptions. A grin spread over his countenance when we said where we had just come from.

“Did you go candling with him ?" he asked. We explained how it was that we had not done so.'

“Oh, isn't it prime fun !" He was fast getting lively.

He had been of the party the night before our arrival, had got wet through, had disported himself like a grampus in the pool, and had got home with an exulted notion of the sport. Of course we did not undeceive him; but having now got him up to the proper communicative pitch, we proceeded to worm out of him, by dint of much questioning, and much labour in bringing him back to the subject in hand for he would insist upon darting off from it at a tangent to give us collateral evidence upon matters in which we had not the slightest interest-all that he knew of the boring.

From the information thus acquired, as well as from enquiries subsequently made, I learnt that the spot now being bored was about the centre of a very fine property of some 1200 acres in area, granted many years ago to the Rev. Father Therry, and extending across the Barranjuee peninsula from the shores of the Atlantic to those of Creel Bay; the one being its eastern, the other its western boundary. Hence the plain had been christened the Priest's Flat. It had been for some time surmised, taking into account the dip of the coal basin, which crops up to the north at Newcastle, and to the south at Wollongong, that at this spot, which lies so near the northern cropping point, the coal seam might be struck at such a medium depth as would allow of payable working. Somewhere about twelve months ago, the reverend proprietor determined upon trying the experiment, and he has continued perseveringly at the work in spite of every discouragement that has beset him; and certainly he has had in this matter to bear up against contrarieties sufficient to have wearied out the majority of ordinary persons.

At no time have the men employed ever injured themselves by hard work, for the testimony of the natives goes to show that they hung it on most amazingly, and when obliged to do something for their money, rather than sink deeper they would break the auger. On another, occasion, an overseer that was employed bolted with the month's pay of the men, and, not satisfied with that, took also the reverend father's horse, though this was subsequently recovered, but only after paying a pretty Bullish sum for stabling expenses. Just as we visited the spot the 'works were again at a stand-still by the breakage of the apparatus, and the newly-appointed overseer was away in Sydney getting it repaired, whilst the hands were scattered hither and thither. They had at that time got to a depth of 186 feet, but had come upon no indications of coal, if we except the passage of the auger through a 6-inch pipe of coal at a depth of 123 feet. (Since these articles were commenced, I have learnt that the boring has reached a depth of 220 feet), when the work was suddenly brought to a close by the breaking of the auger, and, what was worse, by the cutting portion of it being left firmly embedded in the rock that was then being pierced.

Whilst upon this subject, it may-not be out of place to mention that I visited, though somewhat subsequently to the time now alluded to, the bluff headland almost in an easterly line with the boring, and named by the reverend proprietor St. Michael's Head; and there, at about eight feet above high water mark, and quite open to view, is a thin seam, or, as miners term it, pipe of coal, scarcely an inch in thickness. On examination I found also that very much of the shale, both above and below the seam, bore carboniferous indications-leaves, ferns, &c, being distinctly traceable on the face of the cleavages. Another great discouragement that must have operated very strongly upon the rev. owner has been the expense that the work has entailed on him, in consequence of the bungling inexperience and roguery of the persons who have, until lately, been entrusted with it. On this point I speak only on hearsay, and my information is consequently liable to correction ; but I was told with an air of authority that the cost of sinking had, up to that time, reached very nearly £800, being at the rate of rather more than £4 per foot, whilst the time occupied in sinking had been over nine months, or about twenty feet per month not a foot per diem ! If this was not enough to put an extinguisher upon ordinary enterprise, I can't conceive anything that would be. Under the present management I am informed that the work promises to progress more favourably.

We were not very long in pumping perfectly dry the maritime-looking individual who had charge of the works pro tem ; and, by the way, I would here ask how it is that nearly all the males we have encountered in our tracks have so decidedly nautical an appearance? Can it be that, like the islands in the Pacific have been said to have been, this particular portion of the territory of New South Wales has been peopled by the sole survivors of awful wrecks, by men supposed by anxious friends to have been drowned years ago, and who now turn up mysteriously in this unknown land? or, are the inhabitants of the Peninsula like the Arabs on the African coast, and do they seize and treat as slaves the shipwrecked mariners that are cast amongst them by the Pacific, in its un-pacific moods? or have they fled to these wilds to escape the too fond and anxious enquiries, through the water police, of disappointed shipmasters or deluded agents ? The question is one that perhaps some future Australian physiologist may be tempted to solve.

We parted with our friend with but scant ceremony, he turning on his heel and walking into his tent when we told him, "that was all;" whilst we shouldered our loads and walked ahead. Pushing along the edge of the flat, we crossed the foot of the hill we had not long previously descended, and, passing along an inner one of well-grassed sandbanks, that formed the landmost barrier against any encroachment of the waves, we came after a walk of half a mile to a paddock fence, through a slip panel of which the road evidently ran. Entering the paddock we found the upper part overgrown with young timber, principally wattles, that had sprang up since the cultivation of the toil had been discontinued, whilst about half-way across it we encountered a beautiful stream of running water, bright and clear as crystal, and crossed by a very rustic, and at the same time, very dilapidated-looking bridge. Nat was in the van at the moment, and I was astonished to see him, when he reached the brook, throw down his load and descend the bank to the water. Arrived there, he began hastily selecting some of the darkest leaves of a plant which I now observed grew very thickly on the margin of, and even in the water.

"What's the row ?" said I.

" Watercresses," replied he. "Stunning!"

" I'm there," cried Tom; whilst I made no answer, but slipped my shoulders out of my load, and commenced an attack upon this favourite pungent water plant. We amused ourselves for some five minutes over them, and then, filling our billy with the choicest stems we could find, once more made tracks.

After crossing the creek, we came in sight of a homestead, small but neat, having evidently been only recently whitewashed. The paddock was now clear of all undergrowth, and, as a goodly cluster of large trees, the remnants of the former occupants of the soil, had been left standing round the house, it had an exceedingly pretty and picturesque appearance, its white sides gleaming out markedly from amongst the bright green of the shrubs around it, and the dark and sombre verdure of the forest monarchs that overshadowed it.

"This," said Tom, "is Tom Collins, and he's the man that will show us the cave."

“The cave ?" asked I. "What cave ?".

" You'll see," he answered, "a rum 'un; such a one as you won't find anywhere else within a day's ride of Sydney, I can tell you."

Here was a surprise indeed. I had never, during the whole of my lengthened sojourn in Sydney, heard of this cave, and I don't believe that fifty persons in the metropolis are to this day cognisant of its existence; thus, with a feeling something near akin to that of a first discoverer, I hastened up to Collins domicile.

(To be continued.)

MY HOLIDAY. (1861, August 26). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 3. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13059581

MY HOLIDAY

[CONTINUED.]

(From the Sydney Mail, August 31.)

A tap at the door brought out the mistress of the house, accompanied by her brood of little ones, all fat, chubby, and rosy faced, bearing on their countenances the imprimatur of good health. Having mentioned our errand, we were invited to enter, and we found the interior of the domicile even more neat, and white, and bright, than the exterior, for it was the very beau ideal of cleanliness, and care. The tin-ware which hung from the shelves was polished till it shone like silver, whilst the shelves themselves being of deal, were scoured almost to whiteness. The floor, though an earthern one, was swept so clean that it more resembled a single large slab of stone than what it really was; and the fire in the huge bush fireplace was nicely kept in the centre, each side being swept as carefully as the floor itself had been. The hut had been recently whitewashed throughout, and the whole had such a light and cleanly air as strongly to remind me of some of the farmhouses it has been my lot to visit in the mother country, where, perchance, some notable housewife would take such a pride in polishing that even to the iron hoops of the churn, the piggins or the milk coolers would be burnished up till they resembled steel.

Unfortunately our man, Tom Collins, who knew all about the cave, and who was, in fact, its first discoverer, was absent from home; his brother, however, would very willingly guide us to the spot, so said Mrs. Collins, and waiting the arrival of her brother-in-law, she brought forth a huge jug of milk, from which she desired us to help ourselves; and if Tom and Nat didn't do so to a pretty considerable extent, they made a very good attempt at it, that's all. I verily believe that they would have had impudence enough to have asked for another quart, had not the arrival of Collins frer turned their attention to another quarter. He at once expressed his willingness to conduct us, and furnished himself with a piece of candle, the interior part of the cave being so dark as to require a light for guidance amongst the fallen rocks that encumber it.

He led us off in a straight line from the front of the house to the sea, to a spot where the high wall of rock which is here presented to the waves sinks rather slightly, and a little to the north of the well-known rock, "The Hole in the Wall." Bringing us to the edge of the cliff, he pointed to a bit of a track, down which there had evidently been some slipping and shuffling. This went down for about five feet, and then we could see no more. All beyond that appeared to us, from where we stood, to be blank space; and I had a kind of faint idea that, like Farrell's candleing, this was some more of the peninsularies' fun, and that they let themselves slip down here, shot out into space, and chanced the rest. Tom looked at the track and turned pale. Nat inspected it, and turned up the bottoms of his trousers, a sure sign with him of determination, and about equivalent to the turning up of the coat cuffs by the school boy when he has made up his mind to dare some bigger boy to combat. I have already said what my feelings were, but in the position I occupied, as leader and originator of the expedition, it was necessary that I should set an example of decision, if not of courage. There was a small ledge or platform about three feet down on which the whole four of us could have stood easily ; so down on to this I leaped, with something of the same kind of feeling as Marcus Curtius must have had when he took his leap that everybody has heard so much about. Nat followed very readily, but Tom still hung fire.

"It's only just a little bit that's awkward," said Collins, "after that there's as good walking as there is up above."

But Tom was not to be tempted, and that "little bit" struck terror even to my heart, though I was determined upon prosecuting my discovery to the utmost. From the ledge on which we stood, we could only see just two or three feet' of downright slippery descent, and beyond that nothing but the black rocks two hundred feet below, and the crested waves breaking on them in white foam.

"Follow me," said Collins, as griping a projecting point of rock, he slid down the track, dislodging the stones and pebbles, and sending them rattling down upon the rocks below in a regular shower. In another second he had disappeared, and I heard no smash, no cry of torture, so taking heart of grace, I laid hold of the point of rock - oh, if I didn't hold it tight - slipped down the path, shot round a corner, almost breaking my spine with the twist, found my feet laid hold of by somebody, who placed them firmly upon a stone, and then, looking round, perceived that the worst was really over, and that now there was a good plain track running down to the rocks.

My admiration, however, was somewhat marred by a pair of thick boots which, cocking rapidly down from above, struck me somewhat rudely over the head, and as Nat's feet happened to be in them, and, as wanting the guiding hands that had placed me on the friendly rock, they were thrown wildly about, the blows were rather more than I had calculated upon. Nat soon got his footing, and then began to abuse me for getting in his way instead of apologising for his carelessness. We now shouted to Tom that we were all right and bade him follow. As he saw that the thing was done so easily, he hardly liked to jib, so he sang out to us to wait for him, as he was coming. We looked upwards for him with some anxiety, and in the course of a couple of minutes we had a full view of "the boots." They and they alone stopped in sight for a full minute, and we began to fear that Tom had caught somewhere, when suddenly down came the boots and Tom too, all in a lump, sliding down on the hunkers' after the same fashion as I have seen children slither down a slanting board. He had taken the notion that if instead of griping the cliff as we had done, he stooped down in the way I have described he could guide and check his progress with hands and feet. Here he made a woeful mistake, for the breaks in the descent were too heavy, and poor Tom came jumping down kangaroo fashion, bumping and thumping against the rocks, and so completely done up, that if Collins hadn't caught hold of him, he would certainly have gone bumping and thumping to the bottom.

My admiration, however, was somewhat marred by a pair of thick boots which, cocking rapidly down from above, struck me somewhat rudely over the head, and as Nat's feet happened to be in them, and, as wanting the guiding hands that had placed me on the friendly rock, they were thrown wildly about, the blows were rather more than I had calculated upon. Nat soon got his footing, and then began to abuse me for getting in his way instead of apologising for his carelessness. We now shouted to Tom that we were all right and bade him follow. As he saw that the thing was done so easily, he hardly liked to jib, so he sang out to us to wait for him, as he was coming. We looked upwards for him with some anxiety, and in the course of a couple of minutes we had a full view of "the boots." They and they alone stopped in sight for a full minute, and we began to fear that Tom had caught somewhere, when suddenly down came the boots and Tom too, all in a lump, sliding down on the hunkers' after the same fashion as I have seen children slither down a slanting board. He had taken the notion that if instead of griping the cliff as we had done, he stooped down in the way I have described he could guide and check his progress with hands and feet. Here he made a woeful mistake, for the breaks in the descent were too heavy, and poor Tom came jumping down kangaroo fashion, bumping and thumping against the rocks, and so completely done up, that if Collins hadn't caught hold of him, he would certainly have gone bumping and thumping to the bottom.

We now descended to the rocks by a comparatively easy path, and passing along to the southward of the point whence we had started, we followed the rocks round a small projecting headland, on the south eastern face of which the cave is situated.

It is about eighty feet above high water mark, and about twice that distance from the summit of the headland. When we had mounted to it, and stood at its entrance, we found that a kind of bank or platform had been formed in front of it, covered with coarse grass and with an extensive growth of wild parsley, that seemed to flourish here in great luxuriance. The entrance forms a kind of rude irregular gothic arch, about twenty or five-and-twenty feet high in the centre, - the interior of the cave, that is, its first compartment, being about twice that height, in consequence rather of the descent of the flooring of the cavern than of the rising of its roof. It has evidently at some former period been considerably deeper than it now is, as vast masses of rock that have fallen from the roof above lay strewn about, and heaped upon each other, particularly in the centre, to be gradually, but surely, covered by the fine sand that drifts in with every southerly breeze through the entrance, and also by the guano, if such it may be termed, deposited here by the myriads of bats that make this cavern their home. The first thing that strikes the visitor on entering is a long flaw or rent in the sandstone which is here the prevailing rock. This flaw runs along the centre of the whole length of the roof of the cavern, being about three feet in width, and in a perpendicular position, and is filled up with a highly ferruginous sandstone, sounding particularly hard and metallic when struck.

At about eighty feet from the mouth, the floor is covered with immense boulders of stone that have fallen from the roof of the cavern, and almost block up the way to the second compartment. A great part of these has fallen during the bad weather of the last year or two, a continuous rain, followed by a thunderstorm, being sure to bring down some one or more of the huge projecting masses that bulge out from the roof, and threaten to fall at the smallest provocation. Passing round this heap of debris, we now light our candle, for the mass of wreck so far shuts out the light of day as to render artificial light necessary. We now find ourselves in what may he termed the second compartment, which has a more regularly arched and compact appearance than the first, though it is somewhat smaller, being about twenty feet in height and the same width across, whilst the first is at least forty feet high and as many feet in width. Here we can more clearly perceive the ferruginous character of the interloping seam or flaw that has doubtless been the primary cause of this peculiar formation. The drippings from this perpendicular inset between the native rocks hang down in long rust-coloured pendants of oxide of iron, whilst the rocks on either side are formed in regular horizontal layers, the edges of the different strata, and in fact every protruding point of this part of the cave being covered with a white efflorescence from the phosphate of lime that has gathered on them ; whilst here and there other emanations from the rocks have settled in small chrystals upon its face, and reflect back the rays of the candle in all the gorgeous colours of the prism.

This compartment is the favourite resort of the bats and birds, the lighting of the candle creating a regular commotion amongst the denizens of the place. That they have occupied it for many long years possibly for centuries, is probable from the fact that in rooting among the sand and guano that cover the floor to an unknown depth, Collins informed me that he had met with large masses of an ammoniacal salt, that it must have taken the simple laboratory of nature very many years to bring to the state in which it is found.

This compartment is the favourite resort of the bats and birds, the lighting of the candle creating a regular commotion amongst the denizens of the place. That they have occupied it for many long years possibly for centuries, is probable from the fact that in rooting among the sand and guano that cover the floor to an unknown depth, Collins informed me that he had met with large masses of an ammoniacal salt, that it must have taken the simple laboratory of nature very many years to bring to the state in which it is found.

Somewhere about ninety feet from the heap which I take as forming the boundary between the first and second compartment the cavern narrows very considerably, and we enter by a passage about wide enough to admit four persons abreast into the last chamber of this extraordinary place. As the sides come closer together, so also does the roof descend, and a tall man would here be able, by a good stretch of his arms, to touch the top; and so it runs in for another twenty or thirty feet, sides and top gradually collapsing, until at last there is but the width of the flaw, and scarcely height sufficient for a man to sit down. Here the iron percolations prevail, as in the second compartment those of the lime are most abundant ; and we strike against the interjected seam, and, by dint of much labour and perseverance, chip off from it a piece of rock which has all the appearance of being actually iron in a rude state of preparation. We also see portions of it lying in long seams upon the sandstone rock it has divided, and which appear burnt and charred as though it had been subjected to powerful electric action. We also look back now to the way by which we have entered, and just over the heap of rubbish and natural ruins that impede our sight, we mark the bright light of day, which, from the distance we are placed at, is chastened and subdued almost to a twilight. Everything seems solemn and suppressed; all outward sound is shut out, and there is not even a drip from the roof above to break the pervading stillness. We speak in our ordinary tone, but our voices, crushed down by the massiveness around, sound as if we were conversing in whispers. We are in no grand echoing hall, the work of mans' hands that sycophantly sends back the compliments that are given to his skill. We see before us the work of the Great Architect of the Universe, who labours not by the hand, but employs the meanest and the humblest instruments to do His bidding, and who, with the drop of water or the grain of sand, hollows out mighty caverns, or builds up giant mountains. Nature seems to acknowledge the Almighty presence, and to stand silent and awestruck as she watches the never ceasing work.

Something like these thoughts passed through my mind as I sat at the extremity of the cavern and looked out towards its entrance, a distance of over two hundred feet, and I could see that my companions were also somewhat similarly affected. We consequently retraced our steps with feelings very much sobered from those with which we had entered. Having collected a few specimens from the rocks around, we beat a retreat, and it was like coming into another world when we had emerged from the cave, and the hoarse roar of the waves beating upon the rocks, the songs of the birds, and the numerous and inexplicable sounds of nature and of life, struck vividly upon ears fresh from the oppressive stillness of the cave. We journeyed for some distance round amongst the vast heaps of rocks, on which the waves were breaking lazily though unceasingly, until we had reached St. Michael's Head, where the narrow seam of coal, alluded to in my last, was shown to me, together with the strata of carboniferous shale lying above and below it.

When we had seen all that was to be seen here-abouts, we retraced our steps, the point at which we had descended being the only one by which an ascent could be effected ; and no sooner were we on the back track than we missed Tom. Enquiries were mutually made, and then it was remembered that none of us had seen him since leaving the cavern. I was uneasy. I was fearful that he had fallen down some of the immense crevices that yawned between the vast masses of stone that we had had to traverse on our way; and on our retreat I peered down these as I passed them with a kind of nervous dread on each occasion that I should see his crushed and mangled body lying inanimate at the bottom. We didn't find him in any of these, but just as we were mounting the track up to the first slippery point of descent, we heard Spanker's bark, and looking in that direction saw Tom stalking along the rocks half a mile away, looking for the pathway that he had passed.

A cooey from us showed him his mistake and he was not long in rejoining us, whilst Spanker was so elated that he made a spring up the ascending path in the exuberance of his spirits, but happening to jump rather short, and not being gifted with hands to secure a hold, he came rolling back amongst us, and nearly sent us toppling off the narrow pathway, which we were mounting in Indian file, something after the manner in which children knock down the long files of suppositious soldiers represented by bent cards. By dint of some little muscular exertion, and some pushing and pulling at each other, the ascent was successfully accomplished, and we once more stood upon terra firma, for the vast boulders of rock over which our way had been made was certainly not entitled to that designation. Tom was so elated at finding himself once more safe and sound from an adventure over which, from the very first, as he afterwards confessed, he had had the most painful misgivings, that he fired at and killed the first bird that came across him, the victim in this instance being an unfortunate gill-mocker, who had attracted Tom's attention by several times telling him to " Go back," a piece of advice that, in Tom's then state of mind, must have savoured strongly of sarcasm.

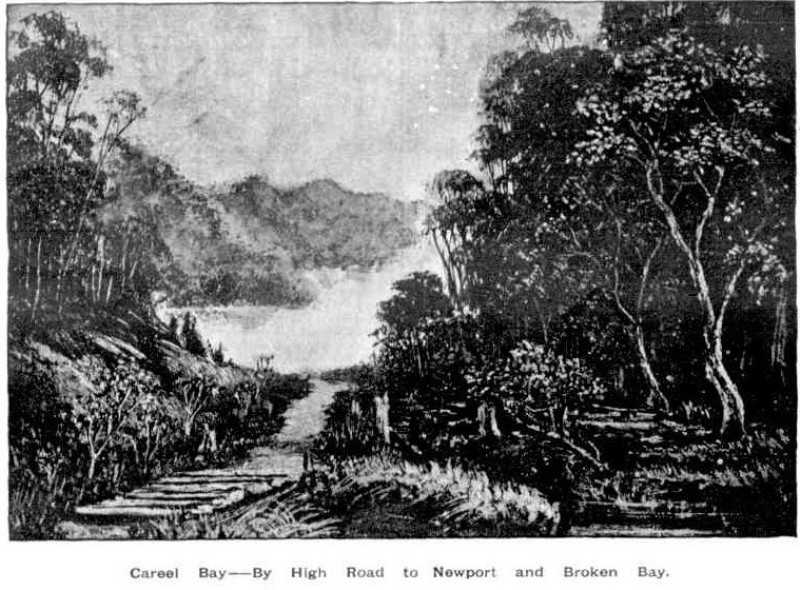

Having thanked Collins for his kindness and attention, we once more pushed ahead, the road now leading us across a long level piece of country that intervened betweeen the sea and the waters of Creel Bay, until it brought us down to the margin of the latter. Arrived here, we had before us as pretty a marine picture as ever painter sketched, and as directly opposite to the one we had but so recently left as could be well conceived. The flat level land had here narrowed to some sixty rods in width, being backed by a heavily wooded range, the base of which was here and there encumbered by large masses of rock, from which the incumbent soil had been washed, and which now protruded in huge boulders, or lay out bare and detached from their native beds. On the margin of the bay were three little whitewashed slab huts with bark roofs, the passion- ate squalling of an infant that proceeded from one of them would have given evidence of their being inha- bited, even if we had not seen two or three barelegged and barefooted children peering at us round the corner of the house.

Through the narrow belt of low swamp oaks that edged the margin of the bay, the clear smooth waters of Creel glistened in the sun, as the gentle breeze swept over its face and slightly ruffled its surface. On the sands, midway between the shore and the retreating water, for it was nearly low tide, two boys were busied collecting shells, by filling an old basket with the sand, and then agitating it in a water-hole, made for the purpose, until the sand was washed away, and nothing was left but the shells that had been mingled with it. These, when washed clean, were thrown into a boat that lay down helplessly on its side close to them. Out on the waters of the bay, floated a smart little cutter, which, though probably only a shell boat, looked from the clear atmosphere, and perhaps also from the fact that she was the only vessel in view, smart and dapper as a yacht, the red shirt and striped cap of the one man on board, adding still farther to the picturesque appearance of the vessel. Behind her again stretched out the waters of the bay, until they encountered the ranges of the other side, which coming down in many a ridge and gully, and forming many a deep indentation or projecting point, gave a gorgeous variety of tints and lights to a background that under a less brilliant sun or less pure atmosphere would have been sombre and monotonous.

Manly to Broken Bay. (1893, November 11). Australian Town and Country Journal (NSW : 1870 - 1907), p. 19. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article71191632

We halted here just long enough to admire the scene, and to have a shot at one of a number of blue cranes, that were stalking about most consequentially and at the same time most warily upon the sands. It was only by dint of a good deal of manoeuvring and dodging that Nat was enabled to get even within possible shooting distance of the rearmost of the lot; and after all, when he fired, he didn't kill his bird. He however succeeded in frightening it, and not only it but all its companions, for they one and all took to flight with a wild cry. But if he had in one quarter caused a fright and a cry he had in another caused a fright and quietness for the report of the gun had stilled the squalling in the hut so effectually that it was not resumed, so long at least as we remained within hearing.

The track, a mere bridle path, now led along the flat, then across a dank luxuriant gully, down which a little stream roared and brattled and foamed with as much fuss and bother as would have been sufficient for a volume of water twenty times its quantity; afterwards, up a wet sloppy hill from which the water exuded in every direction, round the point of the range, down a correspondingly wet and sloppy descent on the other side; and then on to another flat the very counterpart of the one we had just quitted. Another luxuriant and overgrown gully, another wet hill teeming with springs, and then we come down, upon a somewhat broader flat, at the extremity of which we see two tents a short distance apart that we at once recognise, from the description we had received of them, as being the Chinamen's place.

(To be continued.)

MY HOLIDAY. (1861, September 2). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 3. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13057913

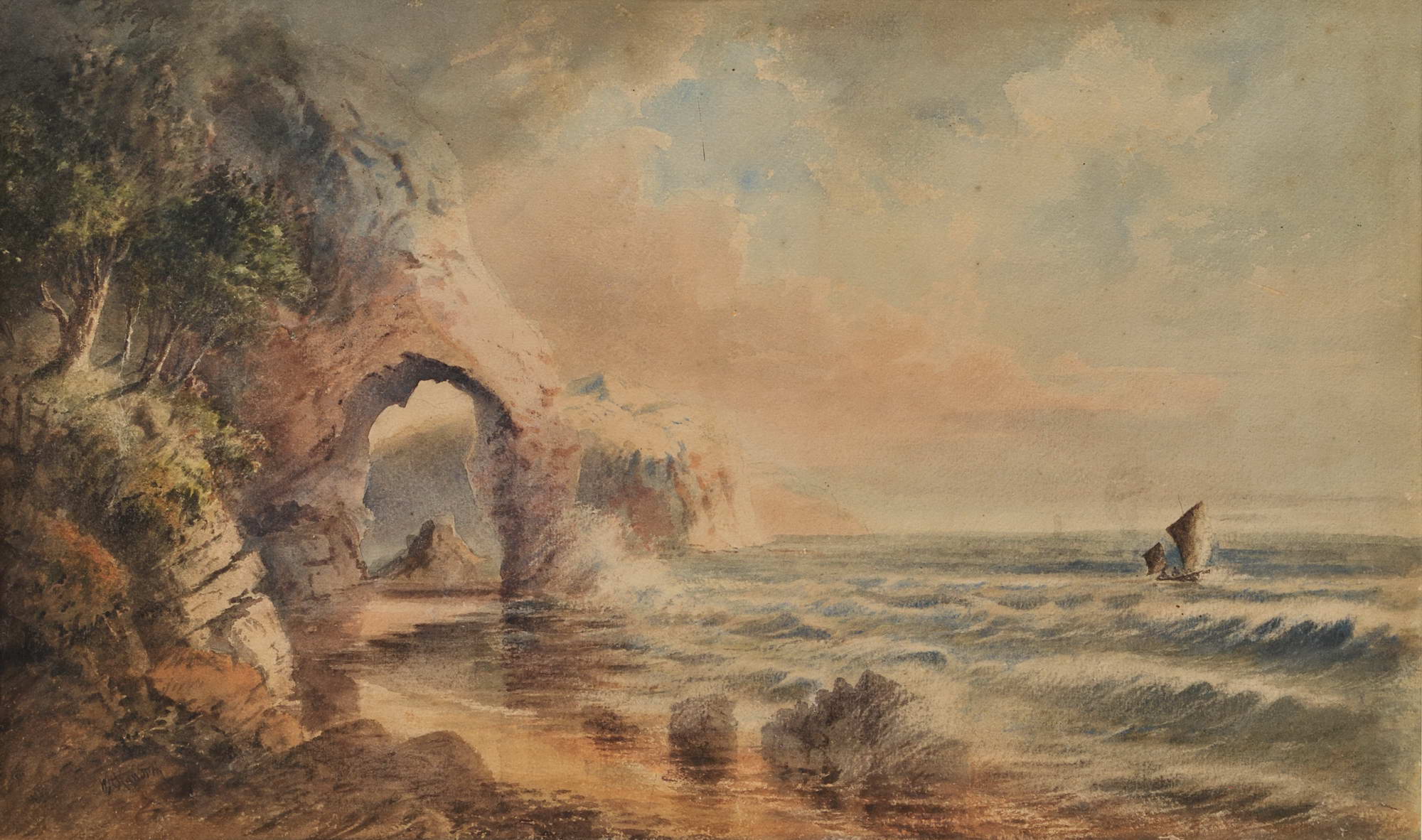

W.H. Raworth (Brit./Aust./NZ, c1821-1904). St Michael’s Arch, NSW [Avalon] c1860s. Watercolour, signed lower left, obscured title in colour pencil verso, 34.2 x 56.5cm. Tear to left portion of image, slight scuffs and foxing to upper portion. Price (AUD): $2,900.00 at:https://www.joseflebovicgallery.com/pages/books/CL181-53/w-h-raworth-c-brit-aust-nz/st-michaels-arch-nsw-avalon

BROKEN BAY.

[FROM OUR CORRESPONDENT]

June 24 – We have had tremendous weather, but, as far as Pitt Water is concerned, no damage has been done with the exception to one of our picturesque curiosities, St. Michael’s Arch. It has at length to the too mighty elements and the destroying influence of time, that which was the admiration of all who have beheld it is now almost baseless fabric-there is only about one half of the outer support left, looking at it at a distance it has the resemblance of a coloured pillar. In its fall it carried a large portion of the overhanging rock with it, a thousand tons of gigantic boulders, and in such masses that I think it will stop the ingress from that part to the cave, but at yet we have had no close inspection for the rollers are dashing to the height of the stupendous rocks. The only idea I can give of the gale is that the froth of (not spray) the sea came over Mount St. Joseph, opposite the house, half a foot in size, and spread itself down to the dam, at times shading the heights of the mountain,-its resemblance was that of an overwhelming snow storm.

The sea at Barranjoey washed away the flower garden in front of the Chinamen's huts, taking soil and all, so that the beach comes close up to their door. There must have been awful havoc in the Hawkesbury, for all the beaches from Barranjoey to the Long Beach are strewn with fragments of houses, boxes, chairs, door frames, dead pigs, hay, wheat, broken bedsteads, weather-board sides of houses, oranges with large branches, pumpkins, melons, corn cobs, and other debris, that scarcely any portion of the beaches can be seen. Mr. Conolly picked up a workbox, in which was contained a number of receipts and letters directed to Mr. Moss, Windsor. The beaches on which are the debris is Barrenjoey, Whale Beach, Collins's Beach, Mick's Hollow Beach, Farrell's Beach, Mona Beach, and Long Beach, so it may be imagined the great extent of destruction. BROKEN BAY. (1867, June 27). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 2. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13144304

This 'Hole in the Wall' was actually at and on the North Avalon rock platform and would acquire other names, such as 'The Pedestal' and ' The lady'. From its earliest times, and before it fell, the 'Hole in the Wall, Barrenjoey' was a landmark for all those at sea:

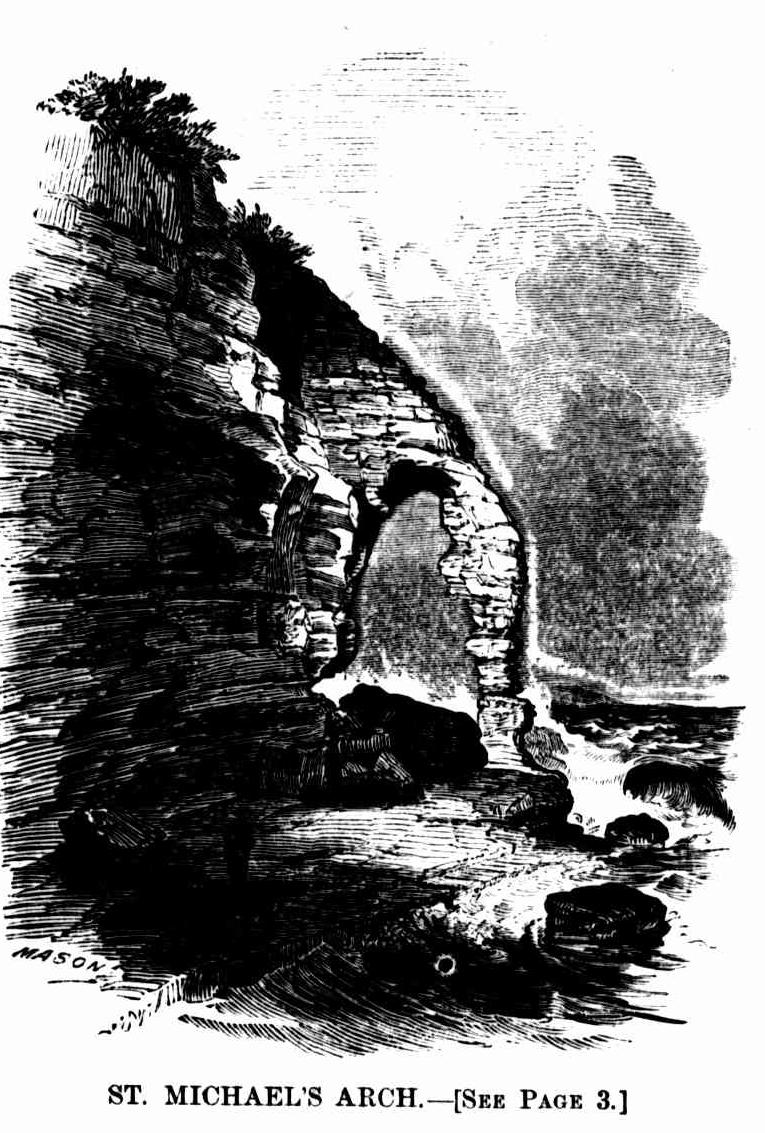

ST. MICHAEL'S ARCH.

This beautiful Arch is situated on the estate of the late Very Reverend J. J. Therry, about three miles south of Broken Bay. As the scenery along. the coast from Manly Beach to the Bay is of the loveliest description, we advise all lovers of the picturesque to hire a spring cart from Mr. Miles - who lives about half a mile from the Pier Hotel - and proceed, early in the morning, to Mr. Collins' house, about thirteen miles distance, so as to be able to inspect this extraordinary specimen of natural architecture, and to return to Manly the same day if necessary.

As this excursion may gradually become fashionable, we quote a description of the places on the road from the late Postmaster- General Raymond's valuable work, the "Post Office Directory for 1855."

"Seven and a half miles from North Harbour, - Jenkins' house; the road for the last mile along a level sandy beach. On the left is Narabeen lagoon. Mr. Jenkins has a snug house here, and much land in cultivation, which is an agreeable prospect from the sea. Eleven and a half miles from North Harbour -Hut on the sea shore. The path from the Pennant Hills Road reaches the sea, and joins this coast road at the farm of one Foley - a tenant of. Mr. Wentworth's; the distance from thence being twelve miles. About half a mile further on is the south-east arm of Pitt Water, on which there are some small cultivated farms. The head of Pitt Water as seen from the heights along which the road or path leads, is equal to any lake scenery, and there are many romantic spots, with good land, on its banks, which might be converted into good farms. Thirteen miles from North Harbour - Several farms and cottages. Fourteen miles- The Rev. Mr. Therry has a grant here. Fourteen and three-quarter miles - The Hole-in-the-Wall, being a rocky projection forming a rude archway with the shore."

The arch mentioned by Mr. Raymond is about twenty-two feet across the inside, and between thirty and forty feet high underneath. The rocks, of which it forms a part, are seventy feet in height - the colours of these rocks are exceedingly beautiful. At low water the visitor can pass through the arch.

Ascending the cliffs, a view of Pitt Water is beheld, being the harbour belonging to this estate. If an arrangement were madeto have a small steamer plying along the beautifully wooded, lofty, and precipitous shores of the Hawkesbury River, parties of travellers could meet it at this spot, avoiding the disagreeable sea voyage by coming from Manly by land. The steamer could convey them from Mr. Collins' house to Windsor, and the trainwould take them back to Sydney - it being understood that the Windsor railway will shortly be completed.

Illustration: ST. MICHAEL'S ARCH. ST. MICHAEL'S ARCH. (1864, October 15). Illustrated Sydney News (NSW : 1853 - 1872), p. 3. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article63512130

circa 1900 when 'the Pedestal'

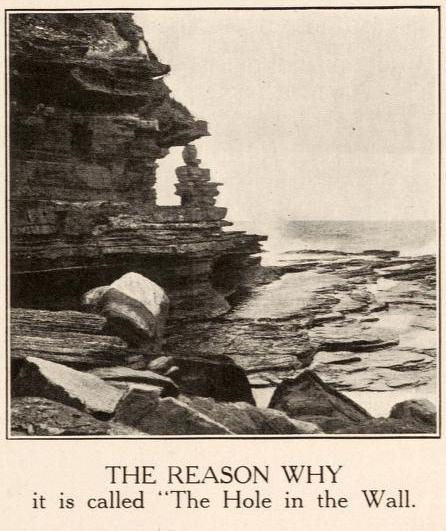

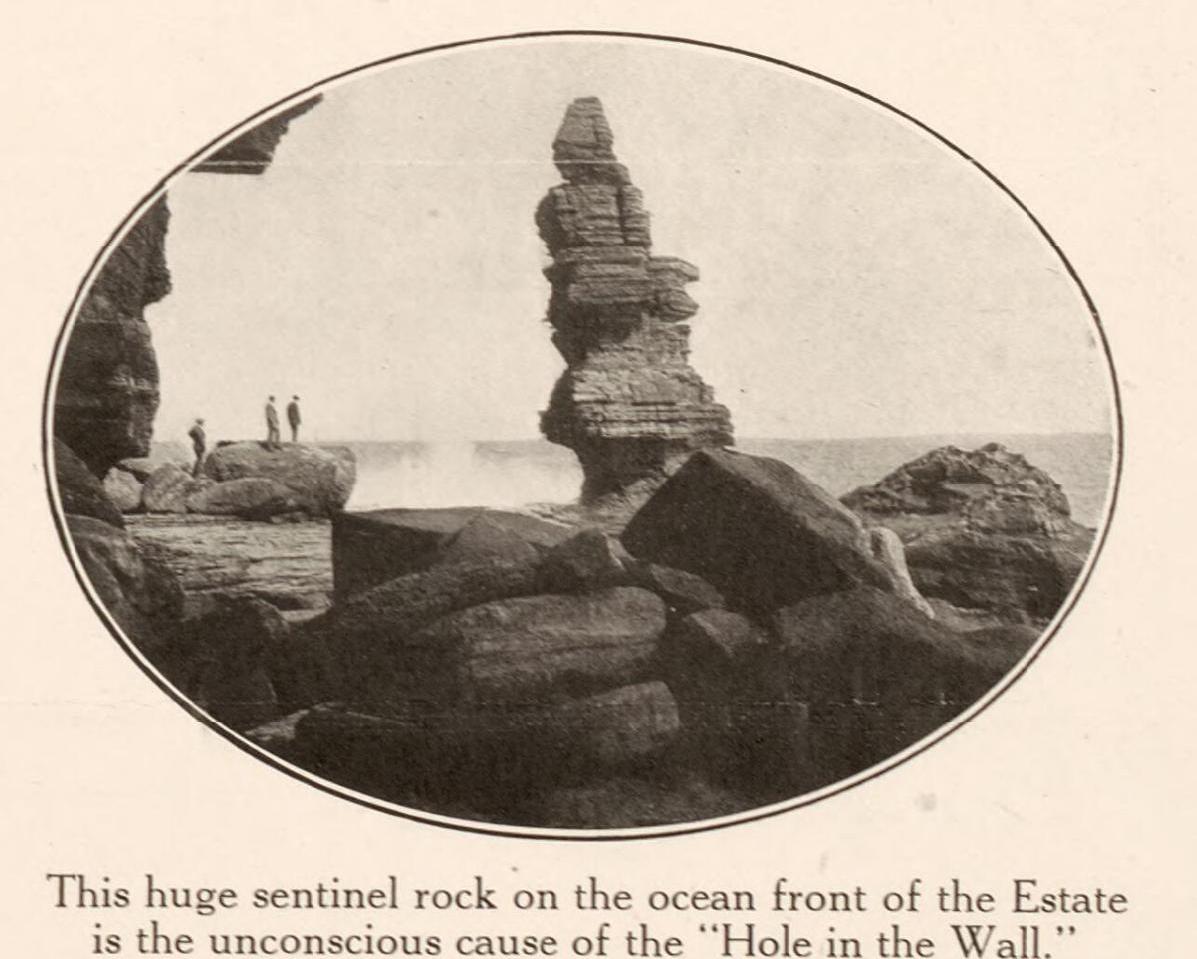

These images from a 1922 sales brochure show not only the change to 'The Pedestal' but also changes in the silhouette of North Avalon Beach headland itself:

From 1922: from Stanton & Son. Careel Ocean Beach estate [cartographic material] : "The hole in the wall", 2nd subdivision, 1922. MAP Folder 37, LFSP 499. Part 1. and Stanton & Son. Careel Ocean Beach estate [cartographic material] : "The hole in the wall", 2nd subdivision 1922. MAP Folder 37, LFSP 499. Part 2., courtesy National Library of Australia.

Another about St Michael's Cave:

A TRIP TO PITTWATER.

Some friends of mine having purchased part of the Pittwater estate recently offered for sale, were anxious to see the land, and they invited me to accompany them. Saturday last was fixed for the trip. On that morning we were all up betimes. The night before we agreed that whoever rose earliest should call the others. Being known to rise on the first sound of the ' cock's shrill clarion,' I was expected to rouse my friends. At 5 o'clock when I went to do so I found that one of them had been up two hours, the others even longer. They had evidently worried themselves into wakefulness all night, for which there was no necessity, as a late sleeper might catch the first Manly boat, by which we were to leave Sydney. Saturday morning broke in smiling silence on the city and suburbs: it was one of those mornings which call forth praise and prayer to heaven for the blessing of such a climate as we enjoy in this Southern land. The waters of the harbour from our point of view (the heights of North Shore)looked like several lakes which were as calm as millponds. Our unrivalled harbour, it appears to me, presents scenes at, daybreak and by moonlight that cannot be viewed at any other time.

In summer mornings, before the sun rises, you may see creeping over the waters of its various nooks and bays gauze-like exhalations, which magnify the ships and boats in the stream. On the appearance of the great, vaporizer the mist is dispelled and the grand picture we all admire is unveiled. The nocturnal beauty of Port Jackson one never ceases to admire. Music only is wanted to make a moonlight view of it one of the most pleasurable sensations. Another harbour, pre-eminent for its capacity and safety,' and no mean rival of our own is more blessed in this respect, for the melody of the Shandon Chimes supplies the void felt here. On this I ponder,

Where'er I wander,

And thus grow fonder,

Sweet Cork, of thee ;

Why thy bells of Shandon,

That sound so grand on

The pleasant waters

Of the river Leo.

On board the Royal Alfred we were joined by a young gentleman who was also a guest. There were not more than half-a-dozen other passengers besides our party. Some of them looked sleepy and sullen, and appeared as if they had parted on bad terms with Morpheus. One of them who was late had to jump on board. The unamiable mood in which he appeared soon gave way to perfect equanimity, the effect, as one observed, of the soothing influence of the incense from the North Shore gums.

"Royal Alfred" at wharf Circular Quay, date; 9/1935 (?!), Image. No: d1_20453, courtesy State Library of NSW.

Arrived at Manly, we had an appetite for breakfast which many might, envy. This watering place reminds one of Passage, which Father Prout describes as situated

Upon the say;

'Tis nate and dacent,

And quite adjacent

To come from Cork,

On a summer's day.

The 'trap' which was awaiting us at, the hotel door, and which had been bespoken, was certainly not one of Kearey Brothers'. It had the appearance of a disused milk-cart., or a superannuated costermonger's conveyance. Our young companion did not like the look of it, but on being told there was no other available for our journey, he had sufficient of the Stoic in him to sink his personal feelings. Needs must when a Manly coach proprietor commands the drive to Pittwater. There is nothing very charming in the neighbourhood of the Pittwater road from Manly. Ducks and water fowl might find it a suitable abiding locality, but Manly-ites, if they have any regard for the future repute of their rising suburb, will extend it on the higher ground Spitwards.

Some four or five miles out of the township we overtook the 'royal mail coach' with its convoy conveying the mails and passengers to Boulton's or Newport at the head of the navigation of the Pittwater harbour. We sailed alone in this company until we crossed the Narrabeen Lagoon. As we emerged there from we descried a church, which appeared to be as well supported as the Smithy described in one of Swift's anecdotes. Seeing no residents around, we inquired where the congregation came from, but our Jehu was not a Matt Ryan. Indeed he was the most taciturn ' whip ' I ever travelled with.

Shortly after we entered upon the estate at Bilgola beach, where there is a deep leafy glen well adapted for the growth of bananas. On ascending to Bilgola Head a splendid view of the coast from Cabbage Tree Head to Barranjoee is obtained. The broad Pacific lay on our right at that moment as placid as Farm Cove. A splendid valley lay before us with the homestead of the patriarch of Pittwater, Mr. John Collins, in the distance; on the left, undulating land, well timbered.

Descending to the valley, we crossed the farm purchased by Mr. Canty, which is believed to be carboniferous. Some years ago competent judges gave it as their opinion that coal existed there. A bore of four hundred feet, made in the ground many years ago, when an attempt was made to test it, passed through strata that indicated the immediate vicinity of the black diamond. Mr. Coghlan's diamond drill would soon settle the question whether coal could be struck there. Mr. Collins's farm is situated in the valley, being flanked on the east by St. Michael's Cave and the South Head of Broken Bay, and on the West by Mount St. Mary. After doing full justice to Mr. Collins's hospitality, we sallied forth under his guidance to survey that part of the estate in which we were interested. We directed our steps towards Long Beach, nearly opposite Scotland Island, Pittwater Harbour. The land improved as we receded from the valley. Indeed we were agreeably surprised at finding soil and slope not excelled by any locality we had seen on the coast, except Irishtown, Lane Cove. My friends were delighted with their investment, and were only sorry they had not purchased more of the land.

Pittwater estate belonged to the late Very Rev. Archpriest Therry, who bequeathed it to the Society of Jesus. It is surrounded on all sides save one by water; and it has been highly praised for its salubrity. It has a Catholic church, at which the Rev. Dr. Hallinan officiates once a month; it has also a Provisional school, attended by some twenty children. There is an incipient town called Brighton at Careel Bay, north-west of Barranjoee. The site is eminently unsuited for a township, and the sooner it is abandoned the better. A low swampy beach from which the water recedes at ebb tide, is not well adapted for settling on. A better site is that on the harbour higher up at Long Beach, where there is ‘ample room and verge ' enough, besides a moderately elevated coast and deep water. West Carbery, as we christened the place, is the site for a township.

A large block of land at Stokes's Point is reserved for a College. The scenery at Pittwater and on the greater part of the way thither is simply grand. When the road is better— (Mr. Collins informed us there is money on the estimates to form it all the way), and when a better style of conveyance is available, I know of no place or drive that will present so many attractions to the invalid, the pleasure or holiday-seeker. Everything conspires to quiet the anxieties of the mind and invigorate the body. Wooded slopes and deep ravines, picturesque views of ocean, beach, and headland, are features that would dissipate the megrims of a miser or restore peace to the mind of a rejected swain. Notwithstanding the discomforts we laboured under from the vile vehicle we had, we enjoyed the trip to and fro uncommonly well, and arrived at 7 in the evening at Manly without any mishap beyond that which a little application of Australian Ointment will remedy, as our young friend of bills and briefs said. CRUIG BARRY.11th May, 1880. A TRIP TO PITTWATER. (1880, May 22). Freeman's Journal(Sydney, NSW : 1850 - 1932), p. 19. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article133488037

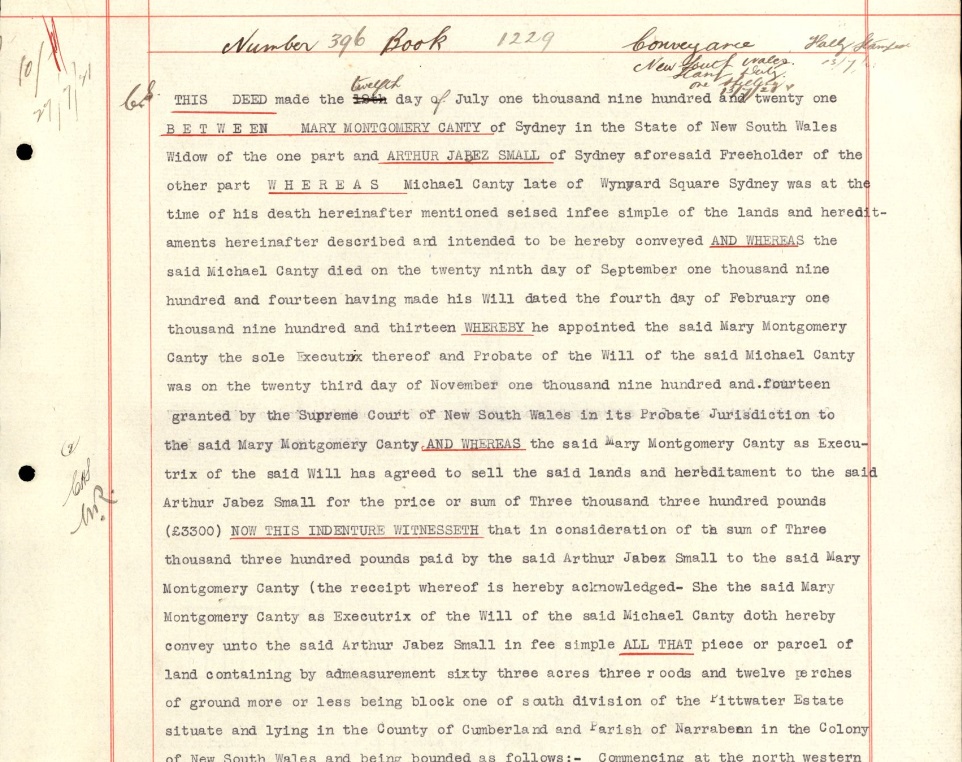

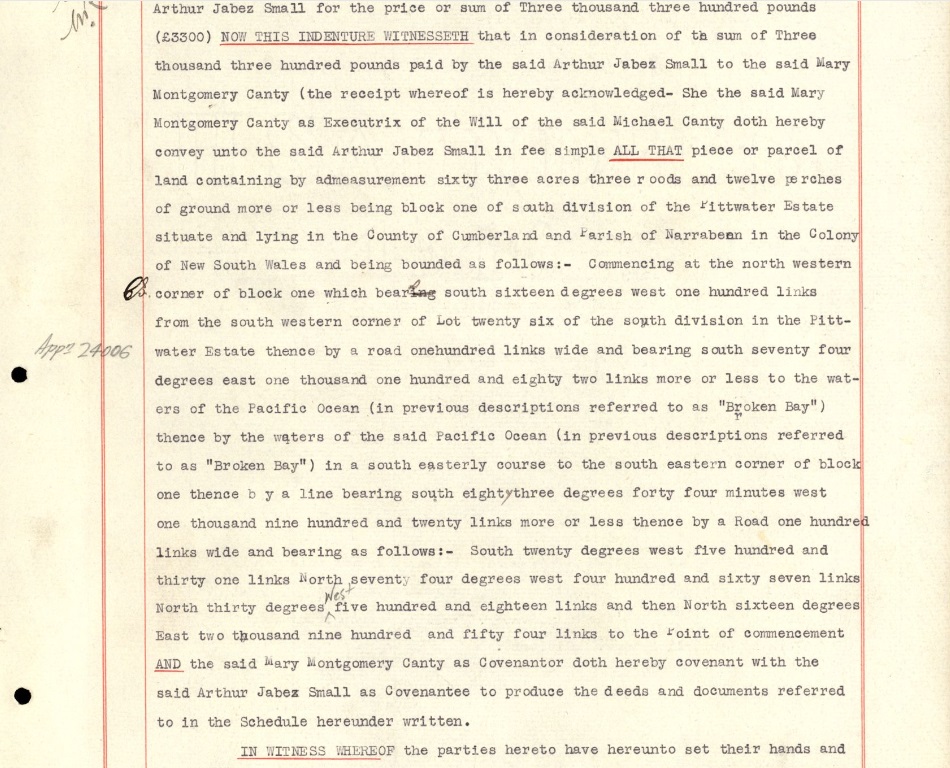

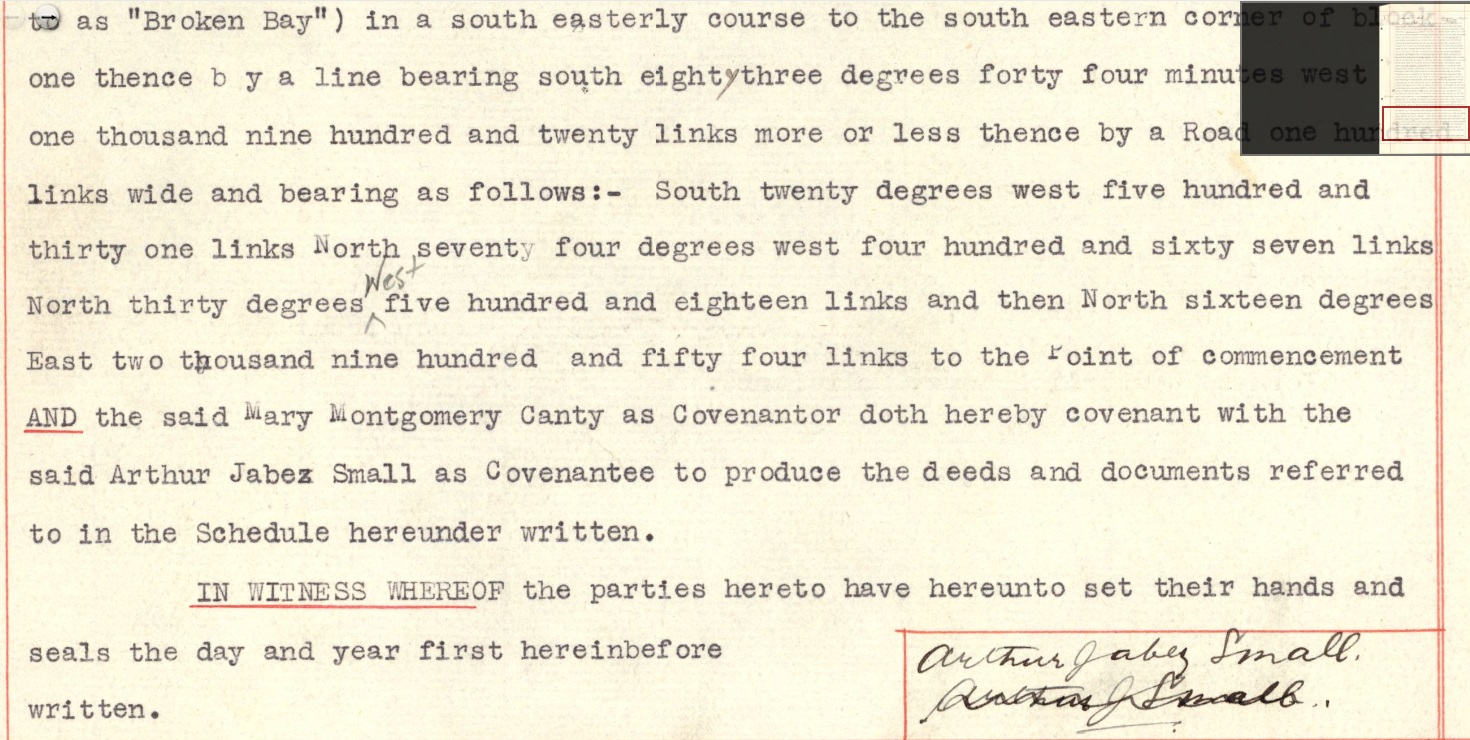

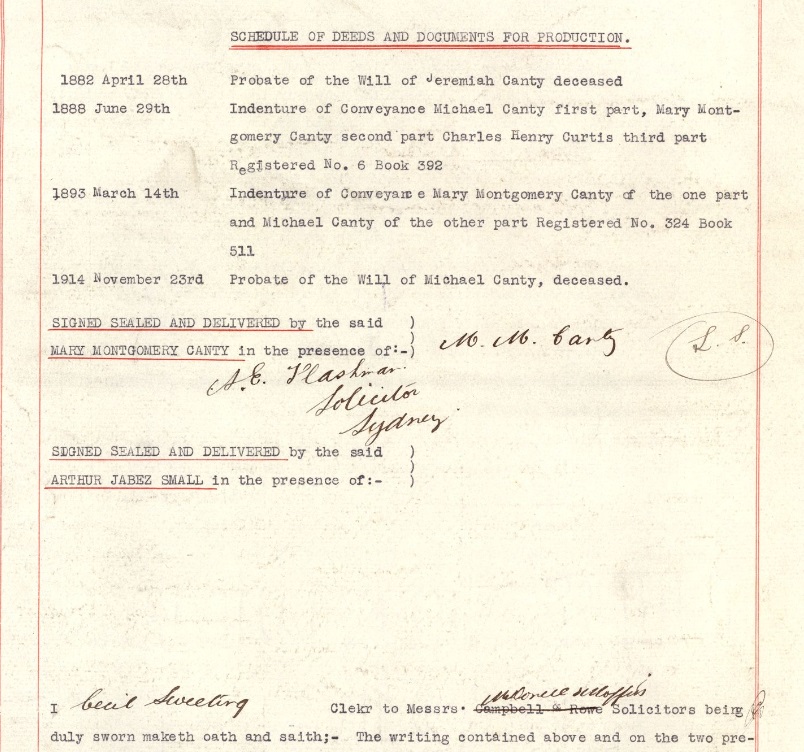

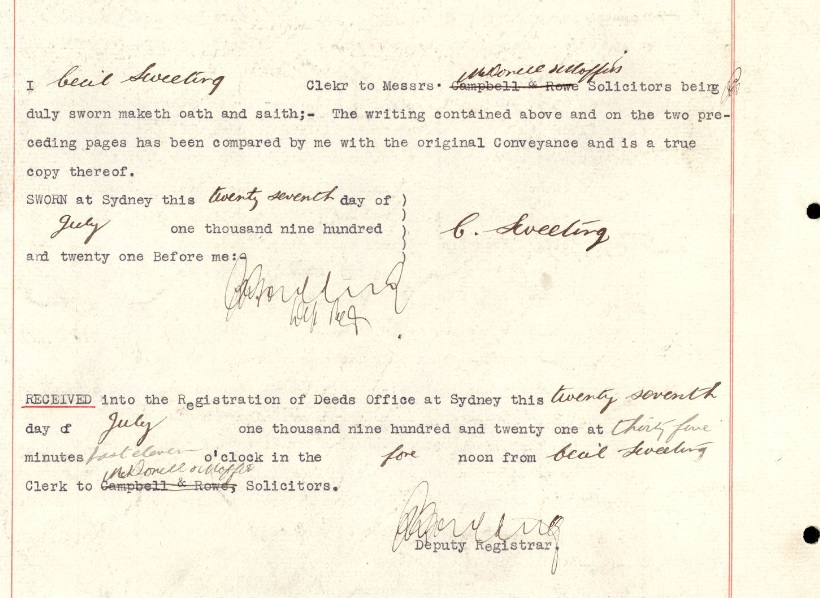

Mr Jeremiah Canty's son, Michael's widow sold his holding to Arthur Jabez Small on the 27th of July 1921 for £3300 NSW Land Records provides:

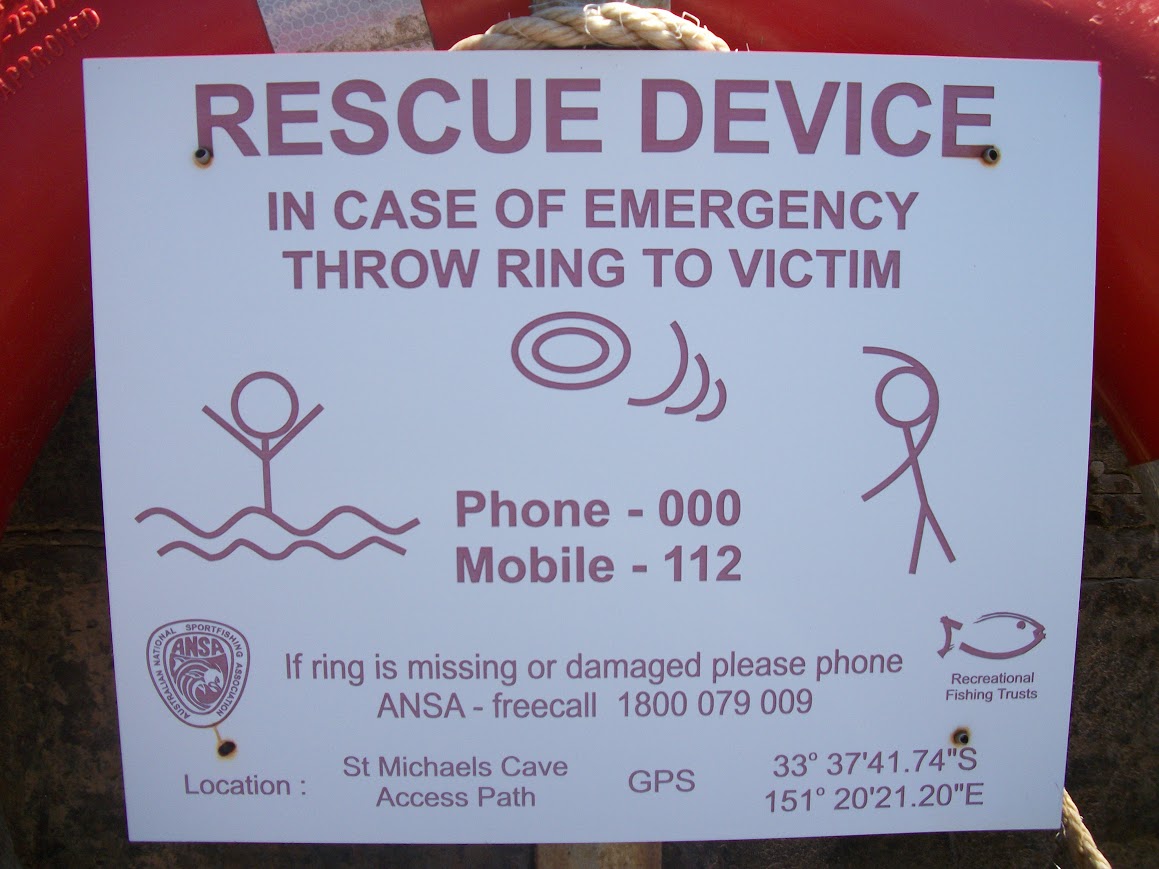

The shelves of rock outside this cave are subject to crashing ocean waves even at low tide in a low swell. The lifebelts that are fixed to cliff faces around this platform today bear testament to how dangerous it may be, even for those experienced with the area when fishing. To imagine dealing with tides and cliffs to get to and from church may have been a good reason not to go ahead with plans to hold services there.

The North Avalon - Bangalley rock platform is a dangerous place to visit and we only ventured there to get the images to go with this page. The 2017 fall of rock at north Avalon Beach headland, sheering off the 'face' referred to by many as 'Michael' is proof that this section of cliff face is susceptible to changes, especially when minor earthquakes occur.

The spot is one that has seen numerous rescues in our times from rock fishermen falling prey to rogue waves and they were receded by others who also swept into the dangerous waters, some not so fortunate:

SWEPT OFF ROCKS. Fisherman Drowned.

James Wise, an unemployed carrier, was swept from the rocks at Avalon on Saturday and despite the attempts of a friend to save him was drowned.

Wise, with his wife and three children, was camping at Pittwater, and was earning his living by fishing. With another man, James Williams, he was fishing on Saturday off the rocks at Avalon at a spot called "The Hole in the Wall ". The sea was rising, and waves were breaking over the men, and Williams suggested that they should move to a higher place. Before Wise could move, a wave swept him away Williams swam out, and struggled to bring Wise ashore for almost 20 minutes. A wave separated them, and Williams was too exhausted to succeed in another attempt at rescue. Narrabeen police were informed of the tragedy, but the body had not been recovered up to lost night.

SWEPT OFF ROCKS. (1932, November 28). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 9. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article16933805

From Issue 270 in July 2016:

Local Heroes Save Rock Fisherman

Therry had cause to begin selling portions of this estate by 1862 and voiced, as part of these plans, a wish for the environs surrounding this headland to remain untouched;

At the end of 1862 Father Therry contemplated selling the Pittwater Estate. The scheme of subdivision was again ambitious. Mr. Elyard, the Surveyor, recommended that "a sufficient portion may be reserved near the water, and possessing the sea breeze, for Public Gardens and games; and also, sites for a School of Arts, Library, Court of Justice and Christian churches. I trust that the trees near St. Michael's Cave may not be touched, and that that spot may not be interfered with by human hands. I think this is the proper way of establishing a city at Broken Bay, and I shall have great pleasure, for my own part, in acknowledging you as its first Bishop." The plan of subdivision was eventually drawn up. The district was to be called Josephton, and the township Brighton. The land was sold in May, 1880. The city of Brighton, and the diocese of Josephton, may come in the future. (O’Brien.1922.P.280).

St Michael’s Cave continued to attract visitors:

AVALON BEACH. HISTORICAL SOCIETY'S VISIT.

Members of the Royal Australian Historical Society on Saturday visited Avalon Beach, between Newport and Barrenjoey, and inspected some of the historic spots in the district. The party was escorted by Mr. Arthur J. Small.

Among the places visited was Bilgola, the beautiful home of Mrs. Maclurcan, which has been erected on the site of the residence of William Bede Dalley, who was prominent in the political life of the State 40 years ago, and who took the initiative in the despatch of the New South Wales contingent to the Soudan. The building is surrounded by tall palms, planted during Mr. Dalley's occupancy of the original cottage.

The site of a coal bore on Avalon golf links was inspected, and St. Michael's Cave, on the Seashore, was viewed by the party. The latter spot was named by Arch priest Therry, who, it was stated, intended to build a chapel in the cave.

At the conclusion of the visit Captain J. H. Watson, president of the Royal Australian Historical Society, on behalf of the visitors, thanked Mr. Small for the visit. AVALON BEACH. (1926, August 23). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 10. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article16329547

Its structure and geological formation has attracted many studies;

COAST STRUCTURE. Cronulla to Barrenjoey.

(BY PROFESSOR GRIFFITH TAYLOR.)

Behind the great beach of Cronulla at its south-end is a line raised shoreline, which Is the result of this upward Joggle. So also the most striking erosion feature of our coast-Saint Michael's Cave at Avalon-was certainly largely cut by the waves, though now a shelf of rock keeps out all action of the sea. Thus we see that the dominant feature of the coast has been a drowning of about 200 foot-but this has been followed by a less striking uplift of about a dozen foot.

COAST STRUCTURE. (1928, March 3). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 13. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article16446582

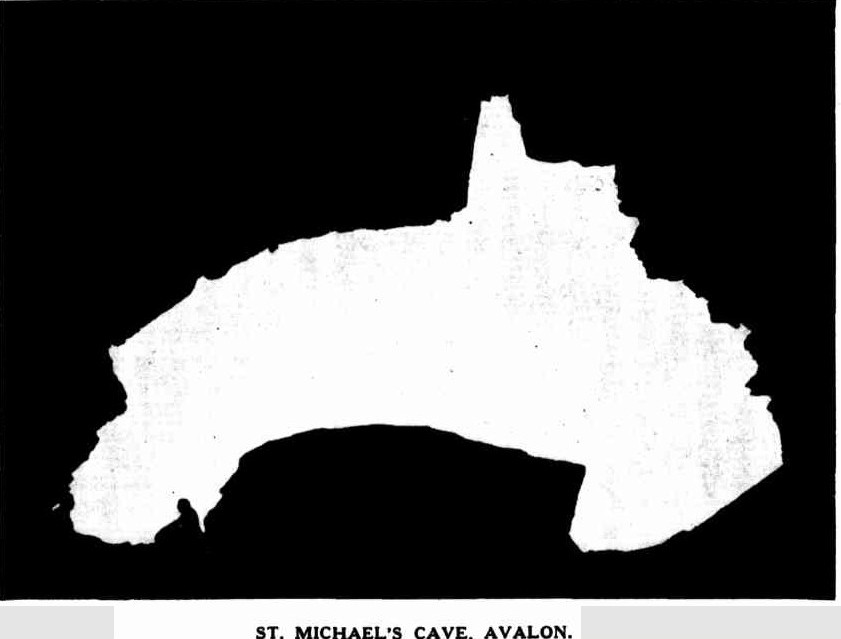

Many saw in its shapes and silhouettes the outlines of Australia itself:

THE VALE OF AVALON. Its Varied Attractions. (BY M. M. CAMPBELL.)

Of all the many beautiful beaches abounding within reach of a short car run from Sydney, surely there is none, which for sheer loveliness, can compare with Avalon. As one tops the rise above it on the road from Newport, the eye rests with delight on the exquisite picture that it forms. Backed by a dense growth of Angophoras and other native trees which clothe the hills behind it, the vale itself lies green and restful, and leads the eye down to the golden crescent of the beach. Beyond the rugged grandeur of the rocky point at the far end of the beach, green headlands run out to meet the ocean, and it is within one of these that a cave of unusual formation is to be found-the peculiarity of which is not observed from the outside; but walk a little way into its dim recesses, then turn and look back, and you will see etched upon the brilliance of the blue water by the outline of the dark entrance rocks,' an almost perfect reproduction of the map of Australia. THE VALE OF AVALON. (1934, April 7). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 11. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article17073748

One recurring theme in these stories is how if you’re standing within it and looking out the silhouette looks slightly like a map of Australia – a very big landscape indeed – constantly changing by being an island always met by ocean waters:

Among the places visited by the members of the. R.A.H.S. was Bilgola, the beautiful home of Mrs. Maclurcan which has been erected on the site of the residence of William Bede Dalley, who was prominent in the political life Members of the Royal Australian Historical Society on Saturday visited Avalon Beach, between Newport and Barrenjoey. and inspected some of the historic spots in the district. The party was escorted by Mr. Arthur J. Small'. The site of a coal bore on Avalon golf links was inspected, and St. Michael's Cave, on the seashore, was viewed by the party. The latter spot was named by Archpriest Therry, who, it was stated, intended to build a chapel in the cave.

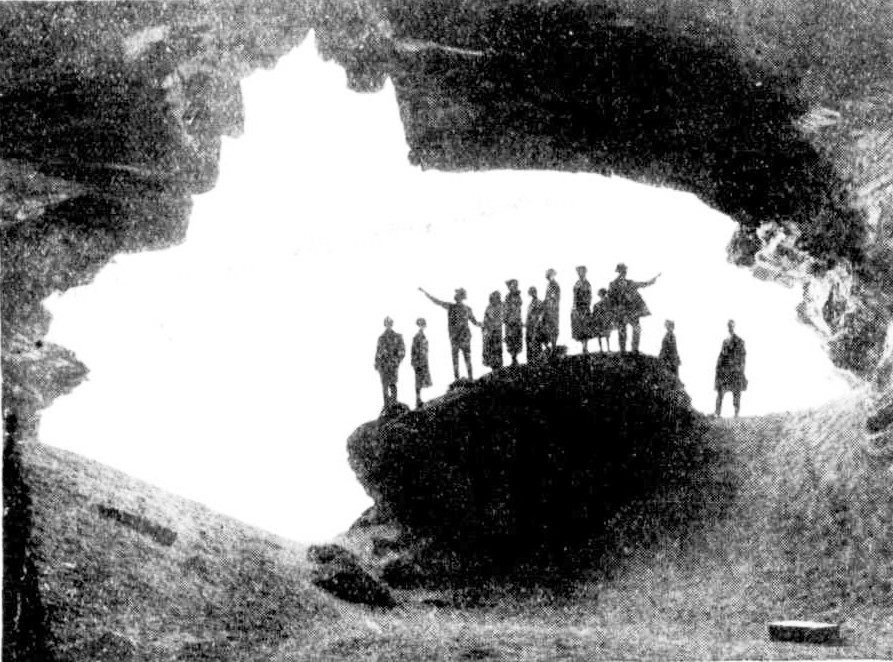

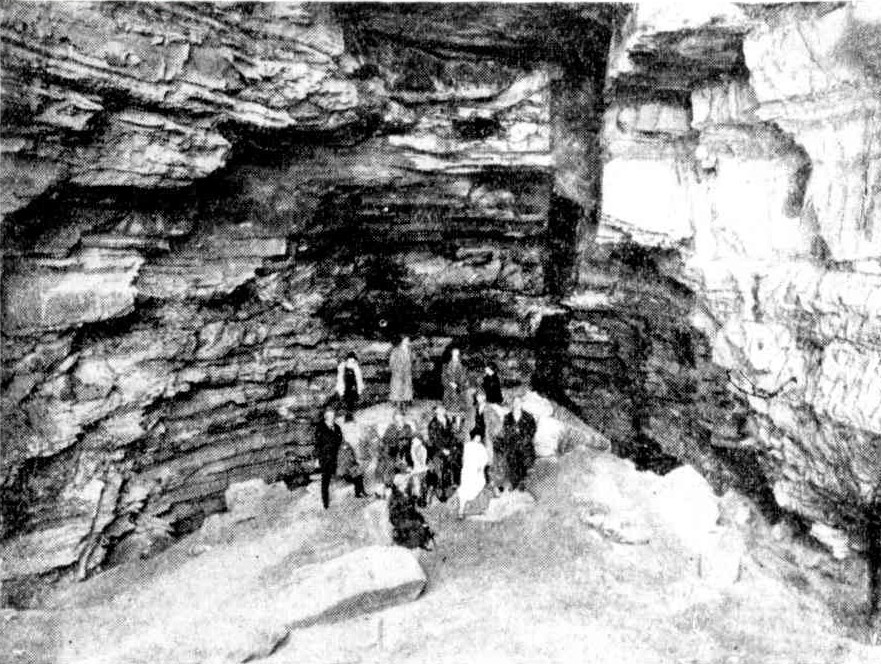

ENTRANCE TO ST. MICHAEL'S CAVE.

MEMBERS OF THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY IN THE CAVE.

A Week-End Miscellany : History, Charity, and Sport. (1926, August 25). Sydney Mail (NSW : 1912 - 1938), p. 10. Retrieved fromhttp://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article166523535

ST. MICHAEL'S CAVE — Avalon's Map of Australia

ST. MICHAEL'S CAVE, AVALON.

A SMUGGLER'S cave in Sydney? Yes!... St. Michael's Cave at Avalon —an ideal spot for an unusual picnic. Those who own cars can go direct; others, to Manly by ferry and then by motor-bus to Avalon. A scramble down the descending cliff face at North Avalon and a longish stiff walk over huge boulders honey-combed by the ceaseless action of the waves lead eventually to acave with a wide, gaping entrance. As the picture shows, it is almost a perfect reproduction in silhouette of the outline of Australia. This is not noticeable until you enter its portals and look seawards. Reputed to be the largest coastal cave in New South Wales, it is said to be capable of holding 2000 people. Its full length is about 325ft, tapering to a narrow point and ending in darkness. The highest point from floor to roof is approximately 30ft.

RECENTLY members of the Naturalists’ Society of New South Wales visited the cave, and Mr. A. J. Small acted as pilot and recalled its history. It appears that in 1833 the Rev. John Joseph Therry had a Crown grant of about 1200 acres in the Barrenjoey Peninsula, most of it then occupying what is now known as the district of Avalon Beach. This reverend gentleman founded the first St. Mary's Roman Catholic Church in Sydney, which, when burnt down some years afterwards, became the site of the present Cathedral. He is credited with the intention of building a chapel above the cave and constructing a passage to the subterranean cavity. This original plan never developed further than the idea and the name St. Michael's Cave, which he bestowed upon it. It is believed by some people that in later years enterprising smugglers accidentally discovered it and used it for their 'unlawful occasions,' quite unknown to the Rev. John Joseph Therry. Others say this is only a legend. Geologists love to delve into the black volcanic dyke which traverses the full length of the roof. This is the result of enormous pressure from unknown depths forcing it upwards. It makes a striking colour streak in the 'ceiling' —almost a modern art decor.

THE floor of the cave is well above sea level. The coastline in this locality has risen far beyond its former level during the ages, and portion of the roof falling in at different times has helped to build up the floor. Several huge boulders now furnish good picnic tables and seats, and gazing upwards you can see marks on the ceiling showing the line of detachment. Breathing an inward prayer that several overhanging projections will remain 'put' during your occupancy, you can picture what a fright the bats must have when these shocks happen. Today the cave with the land above is in the hands of private ownership. It has been suggested that it should be resumed by the State. On a wild stormy winter's day the honey-combed cliffs on the way to the cave, and the exceptionally rugged coast in the vicinity, give a picture of magnificent and unusual beauty. The grandeur of towering waves hurling themselves against the seemingly impregnable fortress of rock is a sight to behold. The naturalists, however, saw it in perfect weather, and the visit to St. Michael's Cave will always remain a memory of delight and adventure and romance in a ;calendar of many happy outings. — M. ST. MICHAEL'S CAVE. (1937, September 1). Sydney Mail (NSW : 1912 - 1938), p. 44. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article160498432

In 1983 part of the cave’s roof collapsed and caused Warringah Council to have an assessment of the cave and its surrounding cliff face access assessed. The report returned by Coffey and Partners stated that the cave and steep paths to it were all dangerous and caused the Council to fence off the stone room in 1985. This fence was replaced by Pittwater Council in 1992 and remains intact.

Above Entrance Sheer Cliff leading up to Fenced

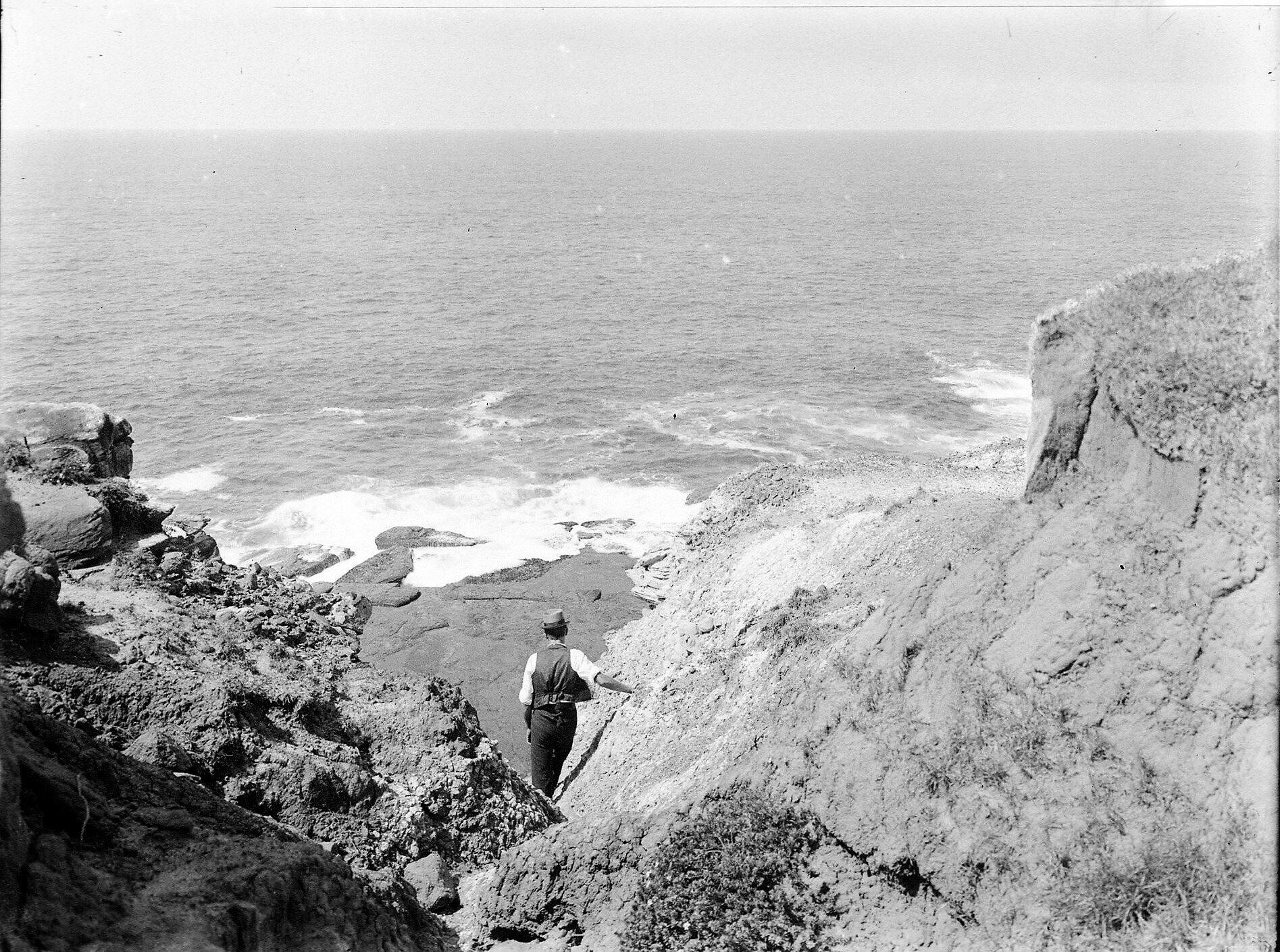

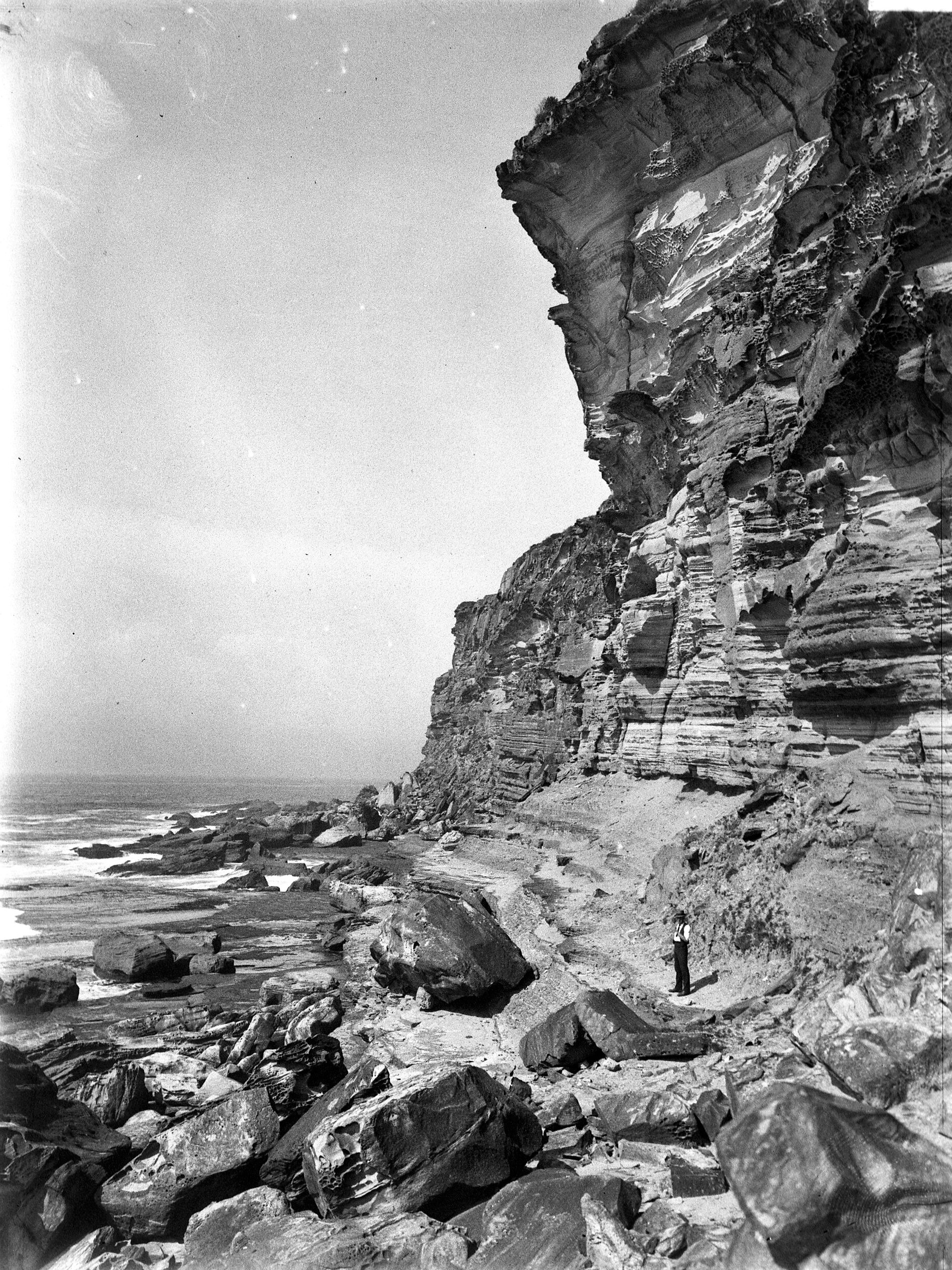

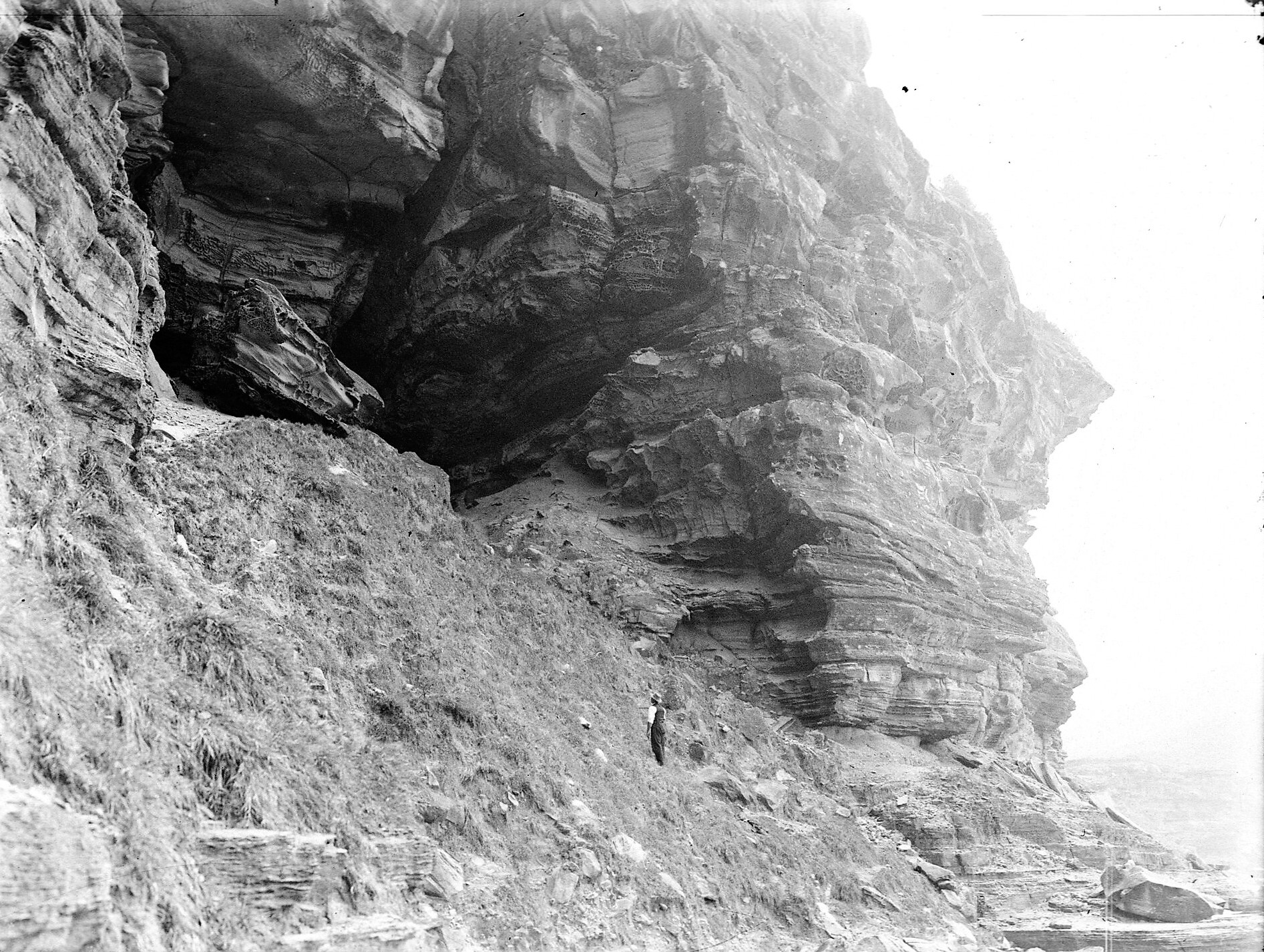

Below run a series of photographs taken in 1912 and digitised by NSW State Records and Archives with another 'local' obviously showing the photographer how to get there. When you take into account that these images were all glass plates, not too light, and the unwieldy camera required to use glass plates, this would have been quite a process for which we today are now grateful. These give us a window into the changing state of this section of our coastline.

Title; Government Printing Office d1_12155 - The Beginning of the way to the Hole in the Wall - [From NSW Government Printer series: Newport]. Contents Date Range; 01-01-1912 to 31-12-1912. File: NRS-4481-3-[7/15965]-St4867.

Title; Government Printing Office d1_12158 - Coast scene in the vicinity of the Hole in the wall - [From NSW Government Printer series: Newport] Contents Date Range; 01-01-1912 to 31-12-1912. File: NRS-4481-3-[7/15965]-St4870.

Title; Government Printing Office d1_12159 - Towering cliffs Hole in the wall - [From NSW Government Printer series: Newport]. Contents Date Range; 01-01-1912 to 31-12-1912. File: NRS-4481-3-[7/15965]-St4871.

Title; Government Printing Office d1_12157 - Nearing the Hole in the Wall - Avalon/Bangalley. [From NSW Government Printer series: Newport]. Contents Date Range; 01-01-1912 to 31-12-1912. File: NRS-4481-3-[7/15965]-St4869.

Title; Government Printing Office d1_12156 - On the way to the Hole in the Wall( just about to climb up)- [From NSW Government Printer series: Newport]. Contents Date Range; 01-01-1912 to 31-12-1912. File: NRS-4481-3-[7/15965]-St4868.

Title; Government Printing Office d1_12151 - The Hole in the Wall - [From NSW Government Printer series: Newport]. Contents Date Range; 01-01-1912 to 31-12-1912. File: NRS-4481-3-[7/15965]-St4863.

Title; Government Printing Office d1_12152 - The Hole in the Wall from outside - [From NSW Government Printer series: Newport]. Contents Date Range; 01-01-1912 to 31-12-1912. File: NRS-4481-3-[7/15965]-St4864.

Title; Government Printing Office d1_12153 - Interior of the Hole in the Wall - [From NSW Government Printer series: Newport]. Contents Date Range; 01-01-1912 to 31-12-1912. File: NRS-4481-3-[7/15965]-St4865.

Title; Government Printing Office d1_12154 - Interior of The Hole, looking out of Hole in the Wall - [From NSW Government Printer series: Newport]. Contents Date Range; 01-01-1912 to 31-12-1912. File: NRS-4481-3-[7/15965]-St4866.