World Wetlands day 2023: Time For Restoration + What's On Locally

World Wetlands Day, celebrated annually on February 2nd, aims to raise global awareness about the vital role of wetlands for people and planet. This day also marks the date of the adoption of the Convention on Wetlands on 2 February 1971, in the Iranian city of Ramsar.

Nearly 90% of the world’s wetlands have been degraded since the 1700s, and we are losing wetlands three times faster than forests. Yet, wetlands are critically important ecosystems that contribute to biodiversity, climate mitigation and adaptation, freshwater availability, world economies, and more.

The UN states wetlands ecological services contribute $47.4 trillion annually to human health, happiness, and security.

In Pittwater there are two major wetlands, the estuarine wetlands of Careel Bay, which were saved by residents from development in 1973, and the sand plain wetlands at Warriewood. Both of these are Environmentally Protected Areas or Wildlife Protected Areas, as is the ongoing regeneration of beautiful Winnererremy Bay. There are also a number of mangrove fringes in Pittwater from McCarr's Creek, to Bayview and Winji Jimmi and the tidal lands surrounding, that provide vital habitat for local wildlife as well as being buffers during storm tides and carbon sinks.

Some of these mangrove areas were quite famous historically, an example being named 'The Maze' on the Pittwater Estuary which although stated as being near Newport and which 'excursionists' who visited over a hundred years ago would hire rowboats to explore, was part of Winnererremy Bay, or what we now call Winji Jimmi. Many of these early reports of those eras described the Water Maze as a 'watery wonderland'.

Water maze, Newport (actually in the corner near Winji Jimmi), ca. 1900-1910, courtesy State Library of NSW.

Mangroves at Bayview, 'The Maze' today. A J Guesdon photo

As residents have seen over January 2022 in Careel Creek Cleaners Inspire A Way Forward For World Wetlands Day 2022 On February 2nd, the looking after these areas is something all of us can do in big and small ways every single day. If you see some rubbish, pick it up. If you see some of the wildlife, look but don't scare them. If you see people taking their dogs into these areas, call them out on it - these places are not for dogs, they are for wildlife to live safely and peacefully. The survival of these local 'critters' is the responsibility of all of us.

At this end of Summer many migratory birds will visit these wetlands to feed so they have enough strength for the long migration back to the northern hemisphere.

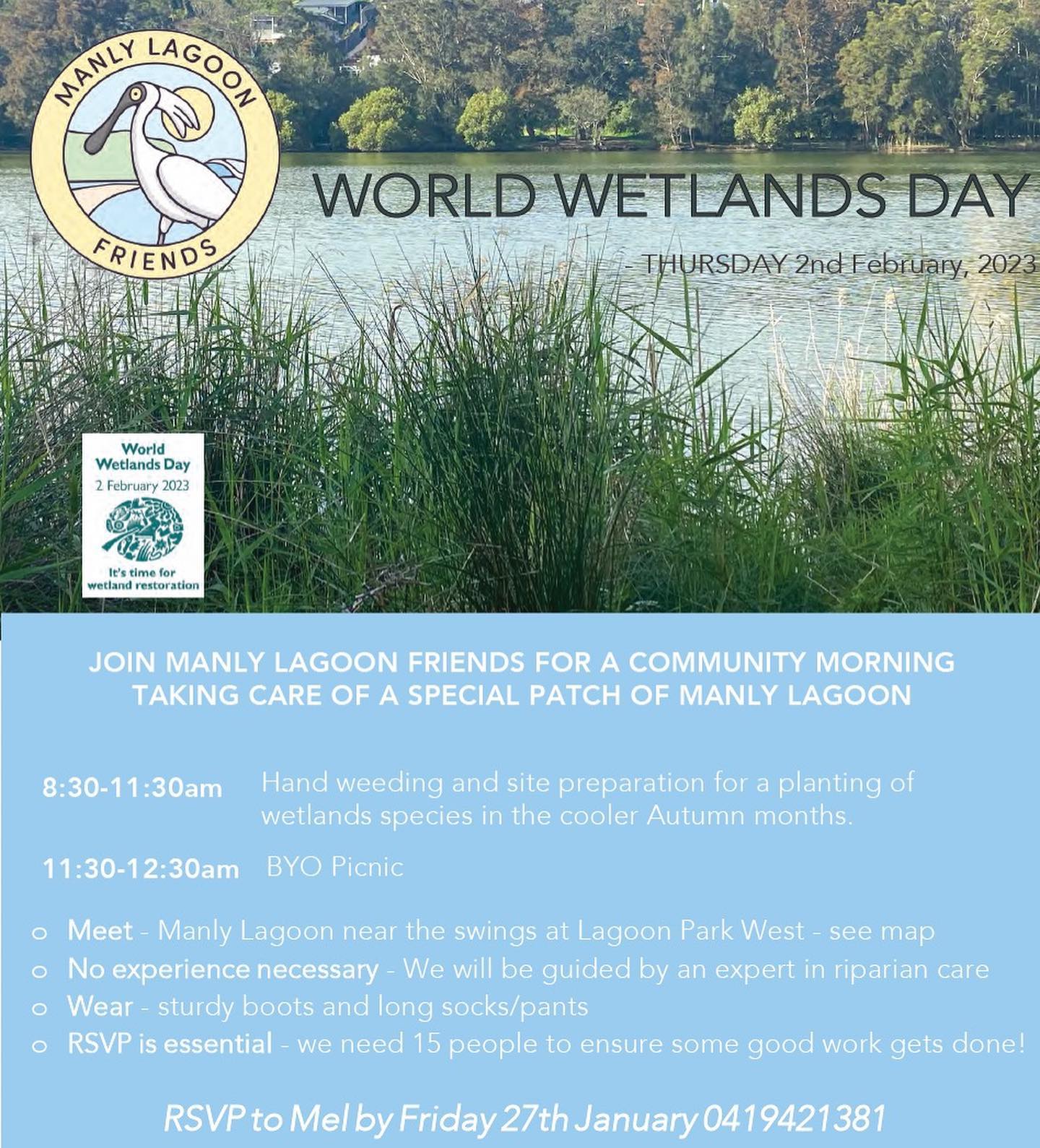

There are also important wetlands at the other end of our peninsula and some events taking place to look after these through education and celebration. Manly Lagoon Friends will be hosting a community morning taking care of a special patch of the lagoon for World Wetlands Day - 8:30-11:30 - bush care, 11:30-12:30 - BYO picnic. Meet - Manly Lagoon park west, near swings.

No experience necessary- we will be guided by an expert in riparian care. Wear - sturdy boots/long pants/socks. Details below - please RSVP to Mel 0419 421 381.

Council are hosting a Wetland's Walk through Warriewood on Saturday, 4 February 2023 - 9:00am to 11:00am. This is a guided walk through the Warriewood Wetlands led by staff from the Coastal Environment Centre. The guide will share information on human connections to the local wetlands, and identify native wetland birds and Flying Fox colonies.

This event is suitable for the whole family. Bookings essential: $10 for a family of 4. Book Online.

Dusky Moorhen, Gallinula tenebrosa - in Warriewood wetlands - photo by A J Guesdon

One of the agreements to come out of the 2022 United Nations’ COP15 nature summit is to see at least 30% of degraded inland water and coastal and marine ecosystems under effective restoration by 2030. This is in addition to increasing protected areas to be 30% of the planet.

Norman Duke, Professor of Mangrove Ecology at James Cook University, wrote an article published in July 2022, 'Climate change killed 40 million Australian mangroves in 2015. Here’s why they’ll probably never grow back' which opens with:

In the summer of 2015-2016, some 40 million mangroves shrivelled up and died across the wild Gulf of Carpentaria in northern Australia, after extremely dry weather from a severe El Niño event saw coastal water plunge 40 centimetres.

The low water level lasted about six months, and the mangroves died of thirst. Seven years later, they have yet to recover. My new research, shortly to be published in PLOS Climate, is the first to realise the full scale of this catastrophe, and understand why it occurred.

This event, I discovered, is the world’s worst incidence of climate-related mangrove tree deaths in recorded history. Over 76 square kilometres of mangroves were killed, releasing nearly one million tonnes of carbon into the atmosphere.

But this event, while unprecedented in scale, is not unique. My research also discovered evidence of another mass die-back of mangroves in the region in 1982 – the same year the Great Barrier Reef suffered its first mass bleaching event.

The mangroves took 15 years to recover. This time, we won’t be so lucky.

Restoration: What Can You Do To Look After Our Local Wetlands?

How we look after our own wetlands is by being conscious of everything that flows into them through local creeks and drains and how we may impact on them if we walk through these fragile ecosystems, or introduce domestic pet species into what are the homes and nurseries of other species above and below the water. The solution there is 'keep them out'. If you see plastics, pick them up and take them home, if you live adjacent to a reserve and have a cat, keep it in at night, if you have a dog, keep it out of the wetlands.

You can also get involved with a local bushcare group that is pulling out weeds or restoring habitat, especially those adjacent to wetland areas or the tidal estuaries that flow in to them. Another great group to be a volunteer with specific to our wetlands and waterways is Landcare's Floating Landcare. This works in our offshore areas like Portuguese Beach clearing rubbish that could be carried by tides into our wetlands or pulling out weeds that could be carried into the creek beds beside them.

Floating Landcare at Portuguese Beach. Photo by Robyn Hughes

The focus of one local group, Living Ocean as part of the Careel Multi Layered Coastal Assessment. This is a detailed study of the Careel marine environment, which is the most significant area of estuarine wetlands on the peninsula.

Conducted over 12 months by the Careel Collaborative, the project will assess Careel on multiple layers: from the state of Pittwater’s largest stand of mangroves and endangered seagrass beds to the levels of macro and micro plastics in the environment and the impact of Careel Creek and stormwater outflows.

Because they form a protective line between coasts and ocean or inland waterways, mangroves are effectively a “plastic trap”. When plastic bags and litter cover their roots and sediment layers, it can starve mangroves of oxygen; and can harm all that depends on them for survival.

Quadrats were set out to search for microplastics along a 50m section of the shoreline. The marine debris and about 5cm depth of sand within each quadrat are sifted and washed to collect microplastics. The finest sieve from each quadrat is placed in a bowl of water so that any microplastics can float and become visible. They are then sorted into different types for analysis.

The team of volunteers will study this area or transect, once a month for 12 months to assess trends as revealed by the data.

Robbi Newman, President of Living Ocean measuring out the area to be studied

Since 2019 Living Ocean’s research arm as also focused on collecting data on microplastics in conjunction with a group called AUSMAP. This is headed up by the Total Environment Centre by Academics, Michelle Blewitt and Scott Wilson, at Macquarie University. This is a world first citizen science project in microplastics. The objective of AUSMAP is to create a heatmap of microplastics in Australia. we want to do is find out how much microplastic is on the beach and what kind is it. We then roll that up onto the database where scientists can study what’s happening.

There are others consulting as well.

Mangrove or Striated Heron Butorides striata - in Careel Creek and Careel Bay Mangroves, July 31st, 2013. Photo: A J Guesdon

Careel Bay forms an estuarine complex of wetland vegetation communities, namely swamp oak woodland, saltmarsh, mangroves and seagrass beds. There are other habitats with less visible vegetation, such as sandy beaches and mudflats with their microfloral communities. There are also transitional zones with sedges and grasses at vegetational boundaries and exotics bordering the residential houses. Many of the plant species present in the estuary are at their northern or southern limit. This makes the bay and its creek of regional as well as local significance.

Careel Bay is a great example of a multi-tiered intertidal wetland system, broken down into the salt marshes, (above the high tide level); mangroves and mudflats, (above the low tide level); and submerged sea grass beds.

Some of the significant features of the vegetation habitats include:

- the complex comprises seagrass beds, intertidal mudflats, Mangrove, saltmarsh, swamp oak Woodland and Swamp Mahogany Forest remnants.

- the mangrove community contains Grey Mangrove and River Mangrove

- the Swamp She-Oak (Casuarina glauca) is also important in that although this species is poorly conserved in the Sydney Region and a food source to the sedentary threatened species Glossy Black-Cockatoo

- extensive intertidal mudflats are present, crucial to migratory waders as a food resource

- seagrass bed includes Posidonia australis at its northern limit, a plant highly susceptible to disturbance and habitat essential for fisheries productivity

- this Sarcocornia dominated saltmarsh is the only one left in NSW

- remnants of an extensive saltmarsh community which is habitat for the threatened Bush Stone Curlew and plant species Bacopa monnieri approaching its southern limit

- the estuarine communities form an important green link with the adjoining Narrabeen Slope Forests of Whale Beach and Avalon

Careel Bay is a site on the East-Asian/Australasian Flyway for migratory wading birds. These arrive in spring from their breeding grounds in Mongolia and Siberia to rest and eat. The Australian people Federal Government is committed to a number of international agreements for the protection of these birds and their habitats, including the JAMBA (Japan-Australia Migratory Bird Agreement) and CAMBA (China-Australia Migratory Bird Agreement).

Posidonia australis, is a species of seagrass that occurs in the southern half of Australia. It occurs in 17 estuaries along the east coast of New South Wales from Wallis Lake to Twofold Bay near the New South Wales/Victorian border. Six locations within New South Wales (Port Hacking, Botany Bay, Sydney Harbour, Pittwater, Brisbane Waters and Lake Macquarie) have suffered significant population decline and have been listed as endangered populations (NSW DPI).

Why is Posidonia australis important?

- It supports a diverse range of fauna, providing habitat, shelter and food. This includes other protected and threatened species such as the White's Seahorse, Little Penguins, Green Turtles, pipefish and seadragons.

- It also provides nursery habitat and feeding grounds for commercially and recreationally important fish species such as bream, sea mullet, leatherjacket, mullet and garfish.

- Protects water quality by filtering the water and removing and recycling nutrients.

- Stabilises sediment on the seabed.

- Improves air quality by taking carbon dioxide gas out of the water and releasing oxygen. The leaves use the carbon to grow and are eventually buried in the sand when they die. This is an example of "blue carbon" - a captive of the seabed and no longer a greenhouse gas in the atmosphere.

- Did you know that seagrasses can bury carbon at a rate 35 times faster than tropical rainforests? True.

To volunteer, contact Living Ocean: please send us your details via email: info@livingocean.org.au or phone: 0410 374 333