North Avalon - Careel Bay Creeks: Some History

Although the presence of fresh water in the form of a permanent spring or creek was a selling point when the big acreage lots were subdivided into urban holdings and sold off, from the 1920's and 1930's on those who had bought these blocks began asking the then Warringah Shire Council to place these creeks into channels and pipes - especially after rain events when the overflow inundated their properties.

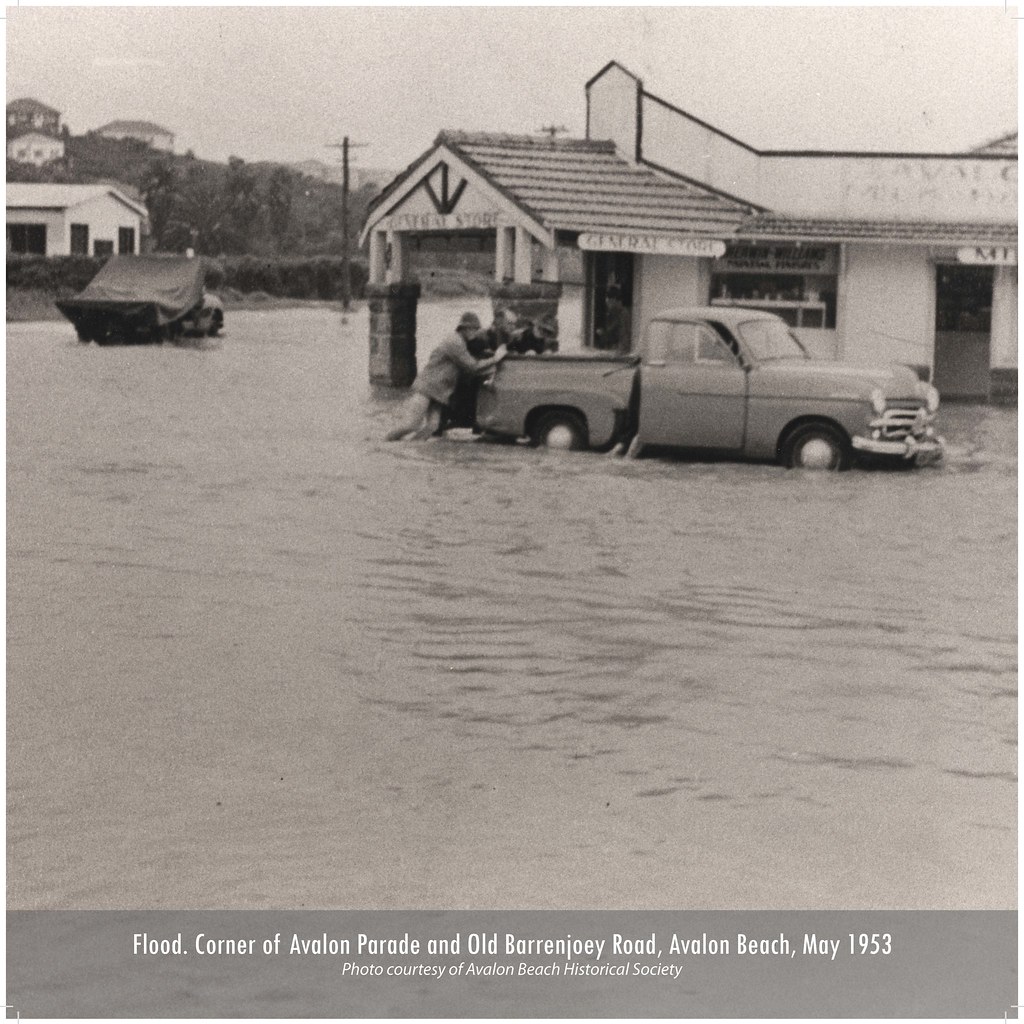

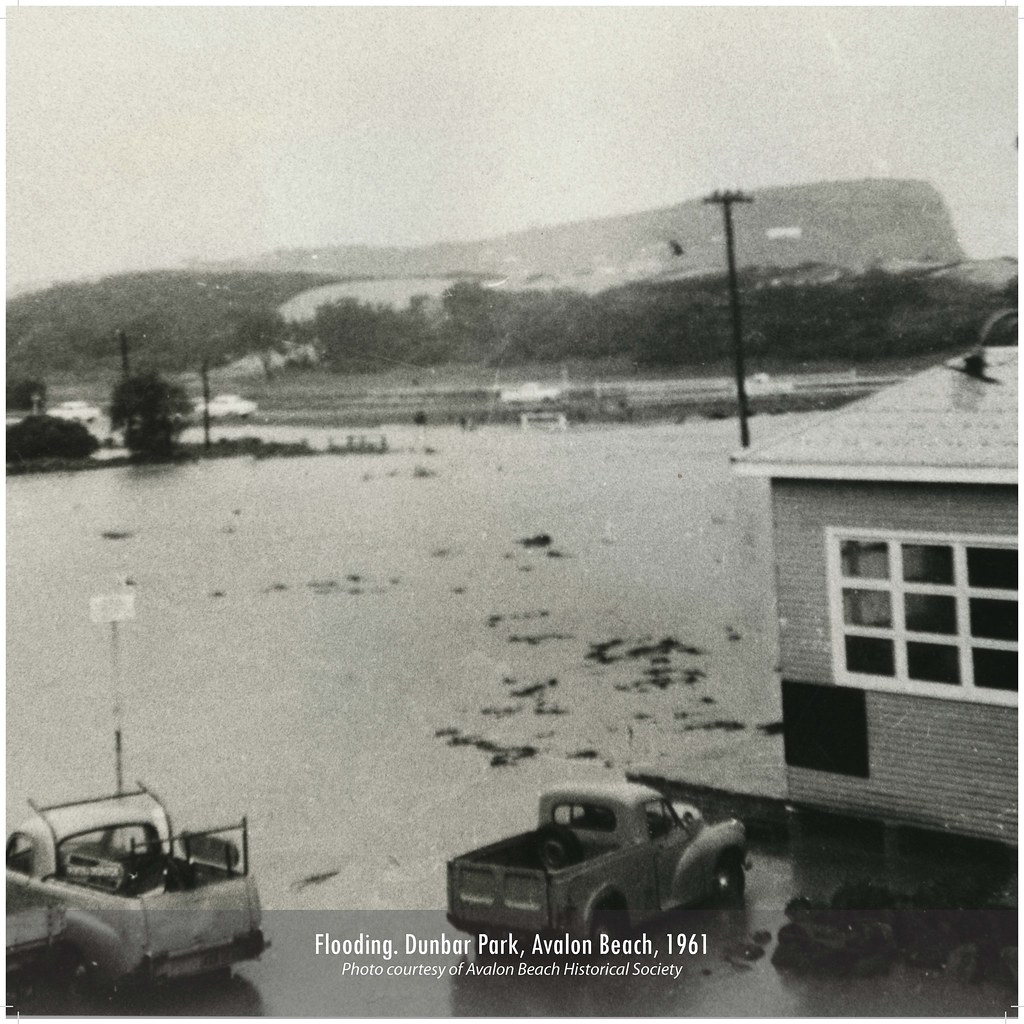

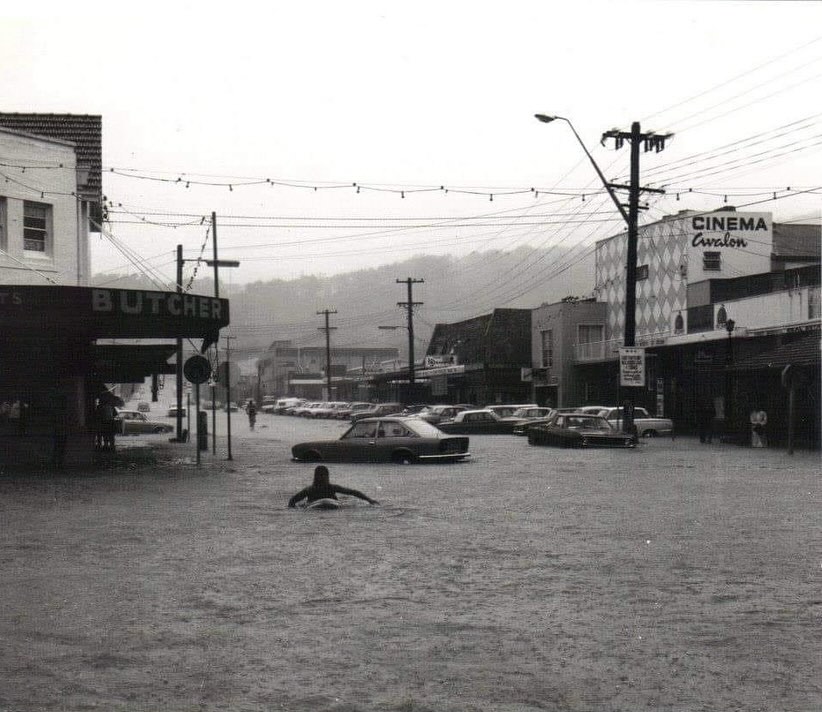

There were at least 7 permanent creeks in the southern end of Avalon Beach and its valley prior to the urbanisation of this place. Residents who moved here in the 1950’s recall how the landscapes would flood from these creek-beds during heavier rains and inundate the shops, the camping area, and some homes.

The waters at the south end, flowing through today's Angophora Reserve, or under Dunbar Park, would join in the Careel Creek channel and flow outwards towards Careel Bay. A pipe bursting in 2024 reminded older residents this is still a place of flooding drains that were former creeks, built on a coastal heath sandflat that is reclaimed mangroves at one end.

However, one generation prior to the great sell-off, a dam was built along Careel Creek to capture this flow of fresh water to serve the cows milked by the Collins family near current day Catalina Crescent.

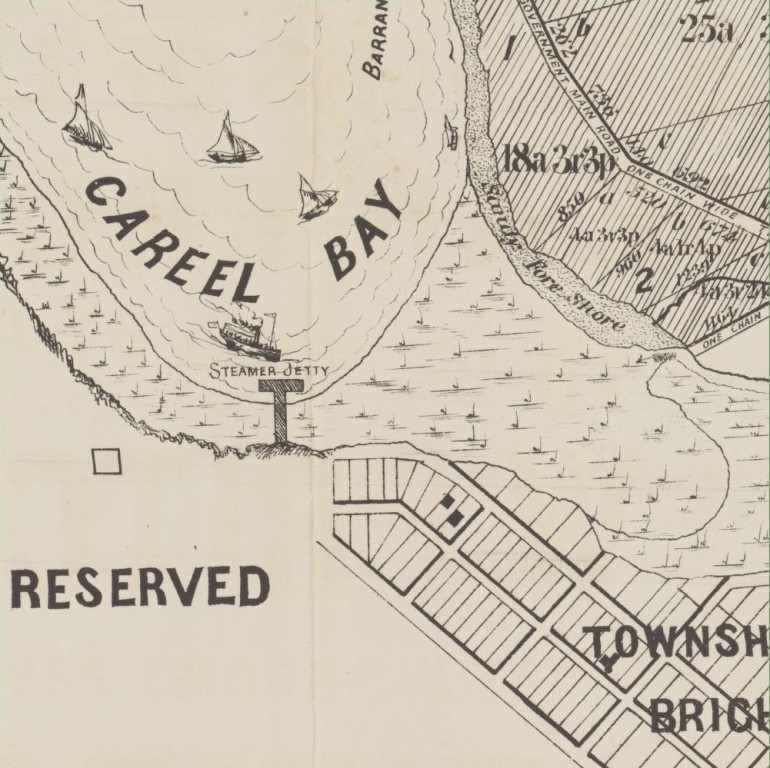

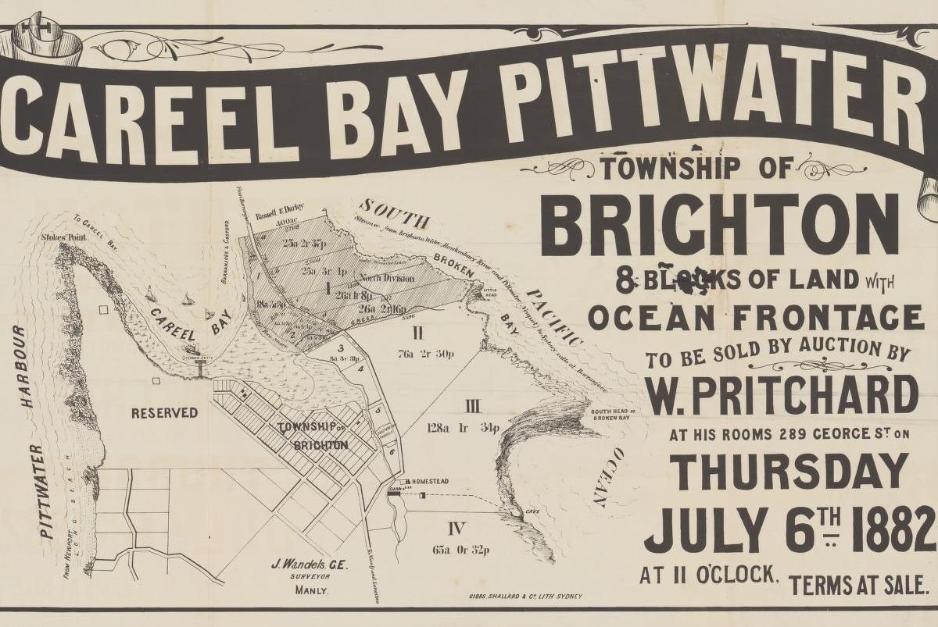

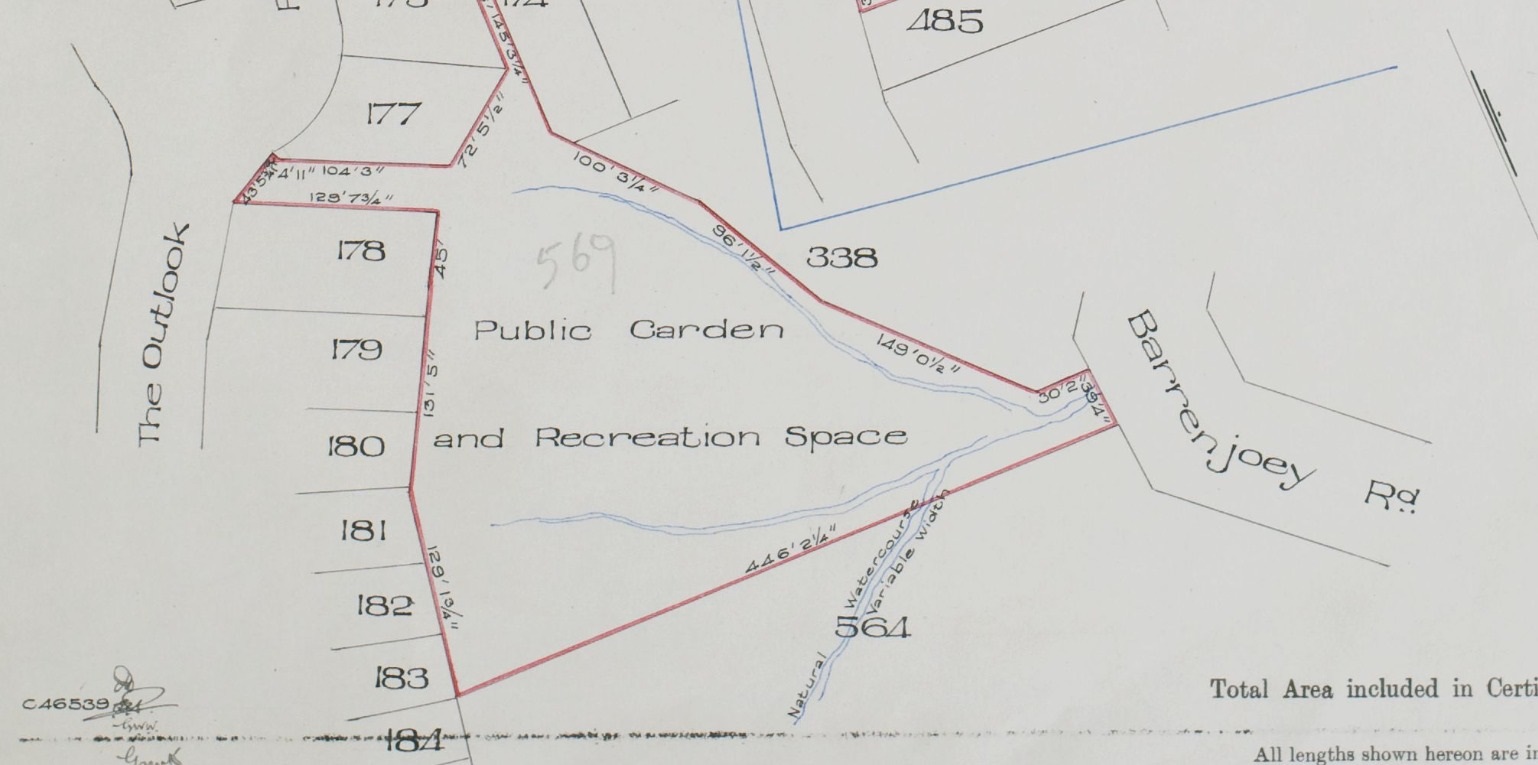

Section from: Careel Bay Pittwater [cartographic material] : township of Brighton, 8 blocks of land with ocean frontage - 1882. MAP Folder 135, LFSP 2160. Courtesy National Library of Australia. Note the placement of the dam and the expanse of mangrove flats marked at the top left of the lithograph leading into Careel Bay

Further north another creek allowed for another dairy 100 years on where fresh water flowed from the north end of what we today call Bangalley Reserve, down through Careel Head road, into Albert and Burrawong roads, and thence once again into the northern end of Careel Creek and Careel Bay.

At the north end of Avalon Beach at least 2 creeks would flow to fill up the current space known as Des Creagh Reserve, one from near the top of Marine Parade, one from the southern corner of Bangalley headland.

In his 1861 published 'My Holiday' Charles de boos describes the valley of Avalon, and to the edge of the Collins place at Catalina Crescent, and to Careel Bay and Snapperman Beach, Palm Bach, from the point of entering and then climbing out of Bilgola Beach, as:

Following the road, we mounted and crossed the range which terminates in the bluff headland, at the base of which I had been so completely drenched on the proceeding day, and then followed a gradually descending track which wound round the hill side into a deep indentation of the land, until it came down to the level of the sandy ridges which bordered the beach, and then dived into a thickly wooded dell, which though so close to the borders of the seam was one tangled mass of vegetation. It was in fact the embouchure of a long gulley, that, separating two extensive and lofty spurs from the main range was so far sheltered by each from the cutting breezes of ocean, as to allow of the growth of every description of plant in we same profusion as in the gullies I have previously described. Through the midst of it ran a tolerably broad sheet of water, the ordinary brooklet of clear, bright, and sparkling water having been transformed by the late rains into a miniature torrent, turgid and bellowing and carrying down before it small boughs and debris from the hills above, in humble imitation of larger streams. By the aid of a fallen tree we managed to cross the stream dry footed, but it was only by breaking down and walking over the branches of the bangolas and by taking advantage of such tufts of grass or such dead timber as offered that we could manage to cross the centre of the gully which the brook had covered with a mimic inundation.

Once through this jungle of a gully, and we had a gently rising road, creeping steadily up the face of the range, by easy graduation until at last it had gained the crest. Then we had a monotonous walk along the top of the ridge, in full view of the vast Pacific to our right, whose waves were now beating almost lazily along the beach at our feet and whose waters had barely swell enough on them to keel over the tiny fleet of coasters that had put out from different ports of shelter on the coast with the first slant of the favouring wind, and were now lying almost motionless, with scarce wind enough to lift their sails. To the left, the hills, covered with the low close scrub common to our coast ranges, bounded our view, the inland ridges, with their heavily timbered sides being hidden from our sight. Suddenly, however, the road took a curve round to the left, crossed a knoll of the range, and then swept down, in some fifty different tracks, on to a broad swampy plain, or flat, which seemed to us to be inundated, for we could see the water sparkling and glistening in the sun over its whole face. I pulled up short here.

" It won't do to go down there, Tom," said I.

"Oh, but we must," he replied. "This is the Priest's Flat, and there, where you see those shears erected, with the two tents alongside of them, is where they are boring for coal. We must go and report progress."

I looked ruefully at Nat, who made no reply, but, grinning viciously, bent down and turned up his trousers to the knees.

“Do you think there are any leeches there ?” I asked. Nat's trousers were instantly turned down again, and this time he didn't grin,

"Oh, no," Tom answered, "there's too much water there for them, and not enough shelter.

I was easier in my mind, though I had my misgivings; but as these Antipodean leeches seemed to be ruled by laws, and to have amongst themselves habits and customs totally at variance with those of leeches in civilised communities, possibly Tom might be correct; so, tucking up my trousers, I prepared to descend. And, after all, when we got down to the flat it was not so bad as it had appeared to us from the hill. The ground was somewhat honeycombed and the water lay in pools, between which however, we managed to find sufficient footing without actually walking in water.

Arrived at the tents, warning of our approach was given by a solitary dejected bark, ending in a melancholy and prolonged howl, from some unseen dog, that was evidently too broken down and low-spirited to repeat the challenge and it was only after we had approached the shears, and had commenced our examination of the boring, which, to tell truth, none of us could make head or tail of, that a tall sailor looking man, who appeared as if he had but just that instant been uncoiled full-rigged from between the blankets, came out to the entrance of one of the tents, and regarded us with an air of blank and sleepy astonishment. Just after him followed his watchful canine guardian, whose short bark and long ululation had effected his master's awakening, but so far behind as not to be within kicking distance; his cowering watchful look, and his tail hard down between his legs, evidently saying as plain as could be said, " I don't know whether I have done right, so I must stand by for squalls."

It took a good deal to waken up our friend to a full sense of the information we required from him, and it was only by the casual mention of Farrell's name that he was brought to his full mental perceptions. A grin spread over his countenance when we said where we had just come from.

“Did you go candling with him ?" he asked. We explained how it was that we had not done so.'

“Oh, isn't it prime fun !" He was fast getting lively.

He had been of the party the night before our arrival, had got wet through, had disported himself like a grampus in the pool, and had got home with an exulted notion of the sport. Of course we did not undeceive him; but having now got him up to the proper communicative pitch, we proceeded to worm out of him, by dint of much questioning, and much labour in bringing him back to the subject in hand for he would insist upon darting off from it at a tangent to give us collateral evidence upon matters in which we had not the slightest interest-all that he knew of the boring.

From the information thus acquired, as well as from enquiries subsequently made, I learnt that the spot now being bored was about the centre of a very fine property of some 1200 acres in area, granted many years ago to the Rev. Father Therry, and extending across the Barranjuee peninsula from the shores of the Atlantic to those of Creel Bay; the one being its eastern, the other its western boundary. Hence the plain had been christened the Priest's Flat. It had been for some time surmised, taking into account the dip of the coal basin, which crops up to the north at Newcastle, and to the south at Wollongong, that at this spot, which lies so near the northern cropping point, the coal seam might be struck at such a medium depth as would allow of payable working. Somewhere about twelve months ago, the reverend proprietor determined upon trying the experiment, and he has continued perseveringly at the work in spite of every discouragement that has beset him; and certainly he has had in this matter to bear up against contrarieties sufficient to have wearied out the majority of ordinary persons.

At no time have the men employed ever injured themselves by hard work, for the testimony of the natives goes to show that they hung it on most amazingly, and when obliged to do something for their money, rather than sink deeper they would break the auger. On another, occasion, an overseer that was employed bolted with the month's pay of the men, and, not satisfied with that, took also the reverend father's horse, though this was subsequently recovered, but only after paying a pretty Bullish sum for stabling expenses. Just as we visited the spot the 'works were again at a stand-still by the breakage of the apparatus, and the newly-appointed overseer was away in Sydney getting it repaired, whilst the hands were scattered hither and thither. They had at that time got to a depth of 186 feet, but had come upon no indications of coal, if we except the passage of the auger through a 6-inch pipe of coal at a depth of 123 feet. (Since these articles were commenced, I have learnt that the boring has reached a depth of 220 feet), when the work was suddenly brought to a close by the breaking of the auger, and, what was worse, by the cutting portion of it being left firmly embedded in the rock that was then being pierced.

Whilst upon this subject, it may-not be out of place to mention that I visited, though somewhat subsequently to the time now alluded to, the bluff headland almost in an easterly line with the boring, and named by the reverend proprietor St. Michael's Head; and there, at about eight feet above high water mark, and quite open to view, is a thin seam, or, as miners term it, pipe of coal, scarcely an inch in thickness. On examination I found also that very much of the shale, both above and below the seam, bore carboniferous indications-leaves, ferns, &c, being distinctly traceable on the face of the cleavages. Another great discouragement that must have operated very strongly upon the rev. owner has been the expense that the work has entailed on him, in consequence of the bungling inexperience and roguery of the persons who have, until lately, been entrusted with it. On this point I speak only on hearsay, and my information is consequently liable to correction ; but I was told with an air of authority that the cost of sinking had, up to that time, reached very nearly £800, being at the rate of rather more than £4 per foot, whilst the time occupied in sinking had been over nine months, or about twenty feet per month not a foot per diem ! If this was not enough to put an extinguisher upon ordinary enterprise, I can't conceive anything that would be. Under the present management I am informed that the work promises to progress more favourably.

We were not very long in pumping perfectly dry the maritime-looking individual who had charge of the works pro tem ; and, by the way, I would here ask how it is that nearly all the males we have encountered in our tracks have so decidedly nautical an appearance? Can it be that, like the islands in the Pacific have been said to have been, this particular portion of the territory of New South Wales has been peopled by the sole survivors of awful wrecks, by men supposed by anxious friends to have been drowned years ago, and who now turn up mysteriously in this unknown land? or, are the inhabitants of the Peninsula like the Arabs on the African coast, and do they seize and treat as slaves the shipwrecked mariners that are cast amongst them by the Pacific, in its un-pacific moods? or have they fled to these wilds to escape the too fond and anxious enquiries, through the water police, of disappointed shipmasters or deluded agents ? The question is one that perhaps some future Australian physiologist may be tempted to solve.

We parted with our friend with but scant ceremony, he turning on his heel and walking into his tent when we told him, "that was all;" whilst we shouldered our loads and walked ahead. Pushing along the edge of the flat, we crossed the foot of the hill we had not long previously descended, and, passing along an inner one of well-grassed sandbanks, that formed the landmost barrier against any encroachment of the waves, we came after a walk of half a mile to a paddock fence, through a slip panel of which the road evidently ran. Entering the paddock we found the upper part overgrown with young timber, principally wattles, that had sprang up since the cultivation of the toil had been discontinued, whilst about half-way across it we encountered a beautiful stream of running water, bright and clear as crystal, and crossed by a very rustic, and at the same time, very dilapidated-looking bridge. Nat was in the van at the moment, and I was astonished to see him, when he reached the brook, throw down his load and descend the bank to the water. Arrived there, he began hastily selecting some of the darkest leaves of a plant which I now observed grew very thickly on the margin of, and even in the water.

"What's the row ?" said I.

" Watercresses," replied he. "Stunning!"

" I'm there," cried Tom; whilst I made no answer, but slipped my shoulders out of my load, and commenced an attack upon this favourite pungent water plant. We amused ourselves for some five minutes over them, and then, filling our billy with the choicest stems we could find, once more made tracks.

After crossing the creek, we came in sight of a homestead, small but neat, having evidently been only recently whitewashed. The paddock was now clear of all undergrowth, and, as a goodly cluster of large trees, the remnants of the former occupants of the soil, had been left standing round the house, it had an exceedingly pretty and picturesque appearance, its white sides gleaming out markedly from amongst the bright green of the shrubs around it, and the dark and sombre verdure of the forest monarchs that overshadowed it.

"This," said Tom, "is Tom Collins, and he's the man that will show us the cave."

“The cave ?" asked I. "What cave ?".

" You'll see," he answered, "a rum 'un; such a one as you won't find anywhere else within a day's ride of Sydney, I can tell you."

Here was a surprise indeed. I had never, during the whole of my lengthened sojourn in Sydney, heard of this cave, and I don't believe that fifty persons in the metropolis are to this day cognisant of its existence; thus, with a feeling something near akin to that of a first discoverer, I hastened up to Collins domicile.

(To be continued.)

MY HOLIDAY. (1861, August 26). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 3. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13059581

MY HOLIDAY

[CONTINUED.]

(From the Sydney Mail, August 31.)

A tap at the door brought out the mistress of the house, accompanied by her brood of little ones, all fat, chubby, and rosy faced, bearing on their countenances the imprimatur of good health. Having mentioned our errand, we were invited to enter, and we found the interior of the domicile even more neat, and white, and bright, than the exterior, for it was the very beau ideal of cleanliness, and care. The tin-ware which hung from the shelves was polished till it shone like silver, whilst the shelves themselves being of deal, were scoured almost to whiteness. The floor, though an earthern one, was swept so clean that it more resembled a single large slab of stone than what it really was; and the fire in the huge bush fireplace was nicely kept in the centre, each side being swept as carefully as the floor itself had been. The hut had been recently whitewashed throughout, and the whole had such a light and cleanly air as strongly to remind me of some of the farmhouses it has been my lot to visit in the mother country, where, perchance, some notable housewife would take such a pride in polishing that even to the iron hoops of the churn, the piggins or the milk coolers would be burnished up till they resembled steel.

Unfortunately our man, Tom Collins, who knew all about the cave, and who was, in fact, its first discoverer, was absent from home; his brother, however, would very willingly guide us to the spot, so said Mrs. Collins, and waiting the arrival of her brother-in-law, she brought forth a huge jug of milk, from which she desired us to help ourselves; and if Tom and Nat didn't do so to a pretty considerable extent, they made a very good attempt at it, that's all. I verily believe that they would have had impudence enough to have asked for another quart, had not the arrival of Collins frer turned their attention to another quarter. He at once expressed his willingness to conduct us, and furnished himself with a piece of candle, the interior part of the cave being so dark as to require a light for guidance amongst the fallen rocks that encumber it.

He led us off in a straight line from the front of the house to the sea, to a spot where the high wall of rock which is here presented to the waves sinks rather slightly, and a little to the north of the well-known rock, "The Hole in the Wall." Bringing us to the edge of the cliff, he pointed to a bit of a track, down which there had evidently been some slipping and shuffling. This went down for about five feet, and then we could see no more. All beyond that appeared to us, from where we stood, to be blank space; and I had a kind of faint idea that, like Farrell's candleing, this was some more of the peninsularies' fun, and that they let themselves slip down here, shot out into space, and chanced the rest. Tom looked at the track and turned pale. Nat inspected it, and turned up the bottoms of his trousers, a sure sign with him of determination, and about equivalent to the turning up of the coat cuffs by the school boy when he has made up his mind to dare some bigger boy to combat. I have already said what my feelings were, but in the position I occupied, as leader and originator of the expedition, it was necessary that I should set an example of decision, if not of courage. There was a small ledge or platform about three feet down on which the whole four of us could have stood easily ; so down on to this I leaped, with something of the same kind of feeling as Marcus Curtius must have had when he took his leap that everybody has heard so much about. Nat followed very readily, but Tom still hung fire.

"It's only just a little bit that's awkward," said Collins, "after that there's as good walking as there is up above."

But Tom was not to be tempted, and that "little bit" struck terror even to my heart, though I was determined upon prosecuting my discovery to the utmost. From the ledge on which we stood, we could only see just two or three feet' of downright slippery descent, and beyond that nothing but the black rocks two hundred feet below, and the crested waves breaking on them in white foam.

"Follow me," said Collins, as griping a projecting point of rock, he slid down the track, dislodging the stones and pebbles, and sending them rattling down upon the rocks below in a regular shower. In another second he had disappeared, and I heard no smash, no cry of torture, so taking heart of grace, I laid hold of the point of rock - oh, if I didn't hold it tight - slipped down the path, shot round a corner, almost breaking my spine with the twist, found my feet laid hold of by somebody, who placed them firmly upon a stone, and then, looking round, perceived that the worst was really over, and that now there was a good plain track running down to the rocks.

My admiration, however, was somewhat marred by a pair of thick boots which, cocking rapidly down from above, struck me somewhat rudely over the head, and as Nat's feet happened to be in them, and, as wanting the guiding hands that had placed me on the friendly rock, they were thrown wildly about, the blows were rather more than I had calculated upon. Nat soon got his footing, and then began to abuse me for getting in his way instead of apologising for his carelessness. We now shouted to Tom that we were all right and bade him follow. As he saw that the thing was done so easily, he hardly liked to jib, so he sang out to us to wait for him, as he was coming. We looked upwards for him with some anxiety, and in the course of a couple of minutes we had a full view of "the boots." They and they alone stopped in sight for a full minute, and we began to fear that Tom had caught somewhere, when suddenly down came the boots and Tom too, all in a lump, sliding down on the hunkers' after the same fashion as I have seen children slither down a slanting board. He had taken the notion that if instead of griping the cliff as we had done, he stooped down in the way I have described he could guide and check his progress with hands and feet. Here he made a woeful mistake, for the breaks in the descent were too heavy, and poor Tom came jumping down kangaroo fashion, bumping and thumping against the rocks, and so completely done up, that if Collins hadn't caught hold of him, he would certainly have gone bumping and thumping to the bottom.

We now descended to the rocks by a comparatively easy path, and passing along to the southward of the point whence we had started, we followed the rocks round a small projecting headland, on the south eastern face of which the cave is situated.

It is about eighty feet above high water mark, and about twice that distance from the summit of the headland. When we had mounted to it, and stood at its entrance, we found that a kind of bank or platform had been formed in front of it, covered with coarse grass and with an extensive growth of wild parsley, that seemed to flourish here in great luxuriance. The entrance forms a kind of rude irregular gothic arch, about twenty or five-and-twenty feet high in the centre, - the interior of the cave, that is, its first compartment, being about twice that height, in consequence rather of the descent of the flooring of the cavern than of the rising of its roof. It has evidently at some former period been considerably deeper than it now is, as vast masses of rock that have fallen from the roof above lay strewn about, and heaped upon each other, particularly in the centre, to be gradually, but surely, covered by the fine sand that drifts in with every southerly breeze through the entrance, and also by the guano, if such it may be termed, deposited here by the myriads of bats that make this cavern their home. The first thing that strikes the visitor on entering is a long flaw or rent in the sandstone which is here the prevailing rock. This flaw runs along the centre of the whole length of the roof of the cavern, being about three feet in width, and in a perpendicular position, and is filled up with a highly ferruginous sandstone, sounding particularly hard and metallic when struck.

At about eighty feet from the mouth, the floor is covered with immense boulders of stone that have fallen from the roof of the cavern, and almost block up the way to the second compartment. A great part of these has fallen during the bad weather of the last year or two, a continuous rain, followed by a thunderstorm, being sure to bring down some one or more of the huge projecting masses that bulge out from the roof, and threaten to fall at the smallest provocation. Passing round this heap of debris, we now light our candle, for the mass of wreck so far shuts out the light of day as to render artificial light necessary. We now find ourselves in what may he termed the second compartment, which has a more regularly arched and compact appearance than the first, though it is somewhat smaller, being about twenty feet in height and the same width across, whilst the first is at least forty feet high and as many feet in width. Here we can more clearly perceive the ferruginous character of the interloping seam or flaw that has doubtless been the primary cause of this peculiar formation. The drippings from this perpendicular inset between the native rocks hang down in long rust-coloured pendants of oxide of iron, whilst the rocks on either side are formed in regular horizontal layers, the edges of the different strata, and in fact every protruding point of this part of the cave being covered with a white efflorescence from the phosphate of lime that has gathered on them ; whilst here and there other emanations from the rocks have settled in small chrystals upon its face, and reflect back the rays of the candle in all the gorgeous colours of the prism.

This compartment is the favourite resort of the bats and birds, the lighting of the candle creating a regular commotion amongst the denizens of the place. That they have occupied it for many long years possibly for centuries, is probable from the fact that in rooting among the sand and guano that cover the floor to an unknown depth, Collins informed me that he had met with large masses of an ammoniacal salt, that it must have taken the simple laboratory of nature very many years to bring to the state in which it is found.

Somewhere about ninety feet from the heap which I take as forming the boundary between the first and second compartment the cavern narrows very considerably, and we enter by a passage about wide enough to admit four persons abreast into the last chamber of this extraordinary place. As the sides come closer together, so also does the roof descend, and a tall man would here be able, by a good stretch of his arms, to touch the top; and so it runs in for another twenty or thirty feet, sides and top gradually collapsing, until at last there is but the width of the flaw, and scarcely height sufficient for a man to sit down. Here the iron percolations prevail, as in the second compartment those of the lime are most abundant ; and we strike against the interjected seam, and, by dint of much labour and perseverance, chip off from it a piece of rock which has all the appearance of being actually iron in a rude state of preparation. We also see portions of it lying in long seams upon the sandstone rock it has divided, and which appear burnt and charred as though it had been subjected to powerful electric action. We also look back now to the way by which we have entered, and just over the heap of rubbish and natural ruins that impede our sight, we mark the bright light of day, which, from the distance we are placed at, is chastened and subdued almost to a twilight. Everything seems solemn and suppressed; all outward sound is shut out, and there is not even a drip from the roof above to break the pervading stillness. We speak in our ordinary tone, but our voices, crushed down by the massiveness around, sound as if we were conversing in whispers. We are in no grand echoing hall, the work of mans' hands that sycophantly sends back the compliments that are given to his skill. We see before us the work of the Great Architect of the Universe, who labours not by the hand, but employs the meanest and the humblest instruments to do His bidding, and who, with the drop of water or the grain of sand, hollows out mighty caverns, or builds up giant mountains. .....We journeyed for some distance round amongst the vast heaps of rocks, on which the waves were breaking lazily though unceasingly, until we had reached St. Michael's Head, where the narrow seam of coal, alluded to in my last, was shown to me, together with the strata of carboniferous shale lying above and below it.

When we had seen all that was to be seen here-abouts, we retraced our steps, the point at which we had descended being the only one by which an ascent could be effected ; and no sooner were we on the back track than we missed Tom. Enquiries were mutually made, and then it was remembered that none of us had seen him since leaving the cavern. I was uneasy. I was fearful that he had fallen down some of the immense crevices that yawned between the vast masses of stone that we had had to traverse on our way; and on our retreat I peered down these as I passed them with a kind of nervous dread on each occasion that I should see his crushed and mangled body lying inanimate at the bottom. We didn't find him in any of these, but just as we were mounting the track up to the first slippery point of descent, we heard Spanker's bark, and looking in that direction saw Tom stalking along the rocks half a mile away, looking for the pathway that he had passed.

A cooey from us showed him his mistake and he was not long in rejoining us, whilst Spanker was so elated that he made a spring up the ascending path in the exuberance of his spirits, but happening to jump rather short, and not being gifted with hands to secure a hold, he came rolling back amongst us, and nearly sent us toppling off the narrow pathway, which we were mounting in Indian file, something after the manner in which children knock down the long files of suppositious soldiers represented by bent cards. By dint of some little muscular exertion, and some pushing and pulling at each other, the ascent was successfully accomplished, and we once more stood upon terra firma, for the vast boulders of rock over which our way had been made was certainly not entitled to that designation. Tom was so elated at finding himself once more safe and sound from an adventure over which, from the very first, as he afterwards confessed, he had had the most painful misgivings, that he fired at and killed the first bird that came across him, the victim in this instance being an unfortunate gill-mocker, who had attracted Tom's attention by several times telling him to "Go back," a piece of advice that, in Tom's then state of mind, must have savoured strongly of sarcasm.

Having thanked Collins for his kindness and attention, we once more pushed ahead, the road now leading us across a long level piece of country that intervened between the sea and the waters of Creel Bay, until it brought us down to the margin of the latter. Arrived here, we had before us as pretty a marine picture as ever painter sketched, and as directly opposite to the one we had but so recently left as could be well conceived. The flat level land had here narrowed to some sixty rods in width, being backed by a heavily wooded range, the base of which was here and there encumbered by large masses of rock, from which the incumbent soil had been washed, and which now protruded in huge boulders, or lay out bare and detached from their native beds. On the margin of the bay were three little whitewashed slab huts with bark roofs, the passionate squalling of an infant that proceeded from one of them would have given evidence of their being inhabited, even if we had not seen two or three barelegged and barefooted children peering at us round the corner of the house.

Through the narrow belt of low swamp oaks that edged the margin of the bay, the clear smooth waters of Creel glistened in the sun, as the gentle breeze swept over its face and slightly ruffled its surface. On the sands, midway between the shore and the retreating water, for it was nearly low tide, two boys were busied collecting shells, by filling an old basket with the sand, and then agitating it in a water-hole, made for the purpose, until the sand was washed away, and nothing was left but the shells that had been mingled with it. These, when washed clean, were thrown into a boat that lay down helplessly on its side close to them. Out on the waters of the bay, floated a smart little cutter, which, though probably only a shell boat, looked from the clear atmosphere, and perhaps also from the fact that she was the only vessel in view, smart and dapper as a yacht, the red shirt and striped cap of the one man on board, adding still farther to the picturesque appearance of the vessel. Behind her again stretched out the waters of the bay, until they encountered the ranges of the other side, which coming down in many a ridge and gully, and forming many a deep indentation or projecting point, gave a gorgeous variety of tints and lights to a background that under a less brilliant sun or less pure atmosphere would have been sombre and monotonous.

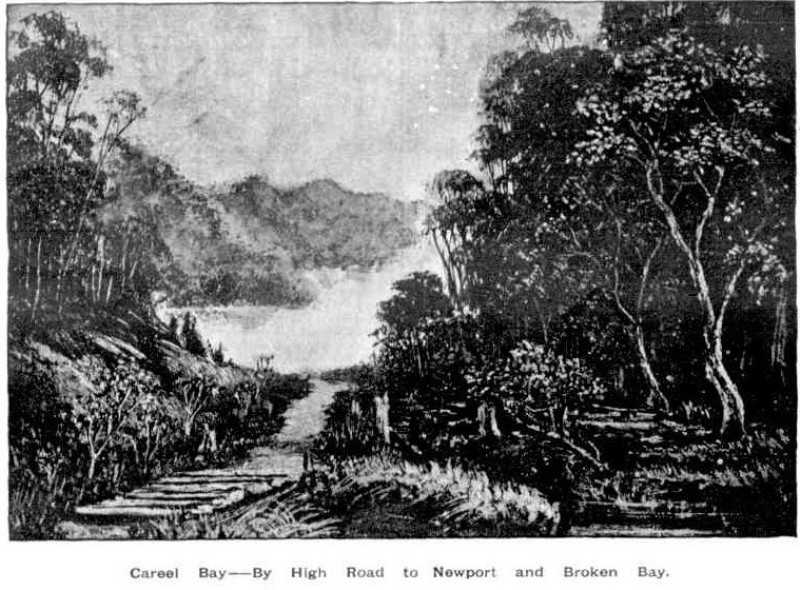

Manly to Broken Bay. (1893, November 11). Australian Town and Country Journal (NSW : 1870 - 1907), p. 19. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article71191632

We halted here just long enough to admire the scene, and to have a shot at one of a number of blue cranes, that were stalking about most consequentially and at the same time most warily upon the sands. It was only by dint of a good deal of manoeuvring and dodging that Nat was enabled to get even within possible shooting distance of the rearmost of the lot; and after all, when he fired, he didn't kill his bird. He however succeeded in frightening it, and not only it but all its companions, for they one and all took to flight with a wild cry. But if he had in one quarter caused a fright and a cry he had in another caused a fright and quietness for the report of the gun had stilled the squalling in the hut so effectually that it was not resumed, so long at least as we remained within hearing.

The track, a mere bridle path, now led along the flat, then across a dank luxuriant gully, down which a little stream roared and brattled and foamed with as much fuss and bother as would have been sufficient for a volume of water twenty times its quantity; afterwards, up a wet sloppy hill from which the water exuded in every direction, round the point of the range, down a correspondingly wet and sloppy descent on the other side; and then on to another flat the very counterpart of the one we had just quitted. Another luxuriant and overgrown gully, another wet hill teeming with springs, and then we come down, upon a somewhat broader flat, at the extremity of which we see two tents a short distance apart that we at once recognise, from the description we had received of them, as being the Chinamen's place.

(To be continued.)

MY HOLIDAY. (1861, September 2). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 3. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13057913

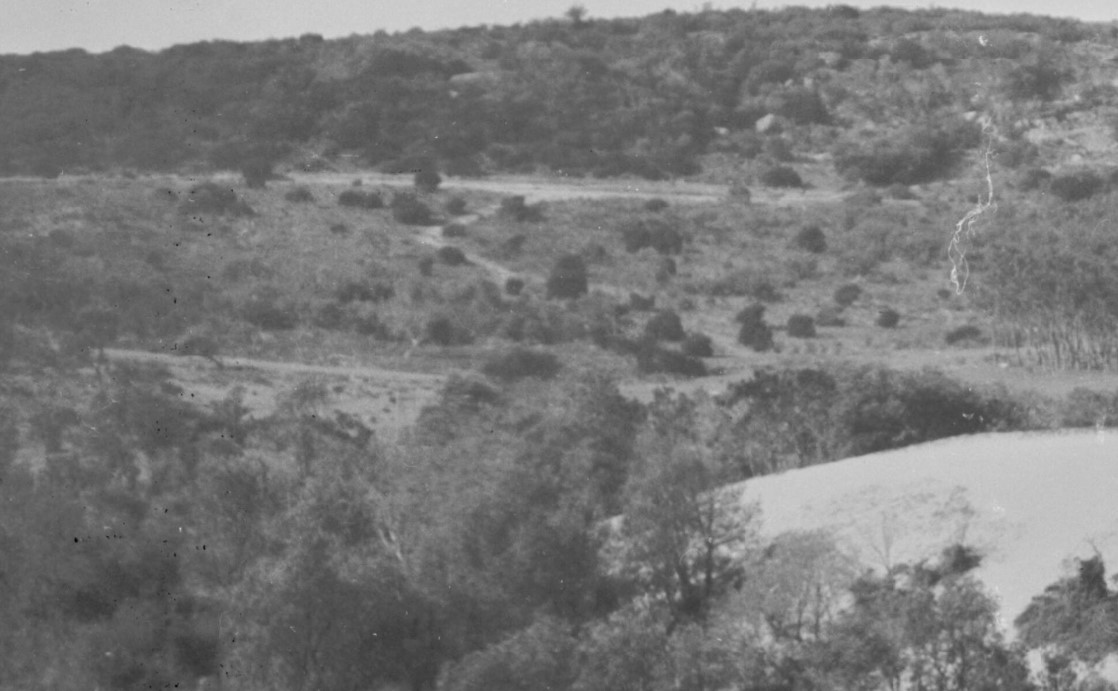

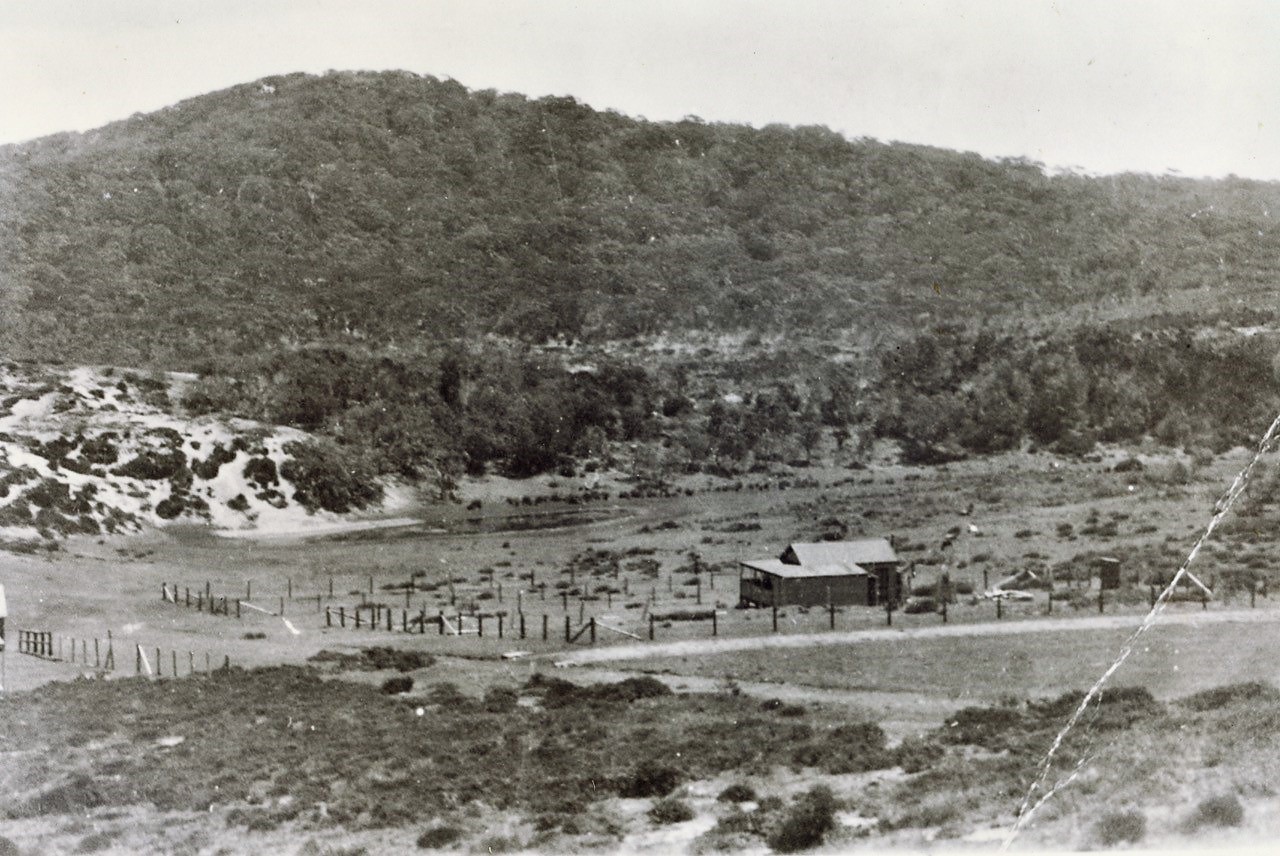

The water everywhere, including 'little streams that roared', can be seen in some of the water tracks that are visible in this panorama of Avalon Beach, which extends into the North Avalon Beach dune area and beyond

Geoff Searl OAM, President of Avalon Beach Historical Society, who has helped with this research, states:

‘This photo from the 1920s shows Miss Madge Breckenridge and a friend on their raft on the pond where water gathered at the bottom of Marine Parade against the Great Northern Spur’. It's looking northwest and Careel Creek would be flowing left to right behind the dune.

It’s possibly taken from what later became Tasman Road, check it against that Careel Estate plan you showed me - 1917/1922! I think her dad bought Marine Parade 1, 3 and 5 (or 3, 5, and 7) before 1920.

Avalon Pano 1: '' This is part of a super panorama taken from the top of North Av headland looking almost due west. In the foreground is a rough old Marine Pde. with a rather clean Harley Road ducking off to the right. There is the tiniest hint of Tasman Road to the right of the cottage which picks up the fence line at the bottom of Marine Parade.''

Almost in the middle of the pic is the pond on which Madge and friend were paddling about on.

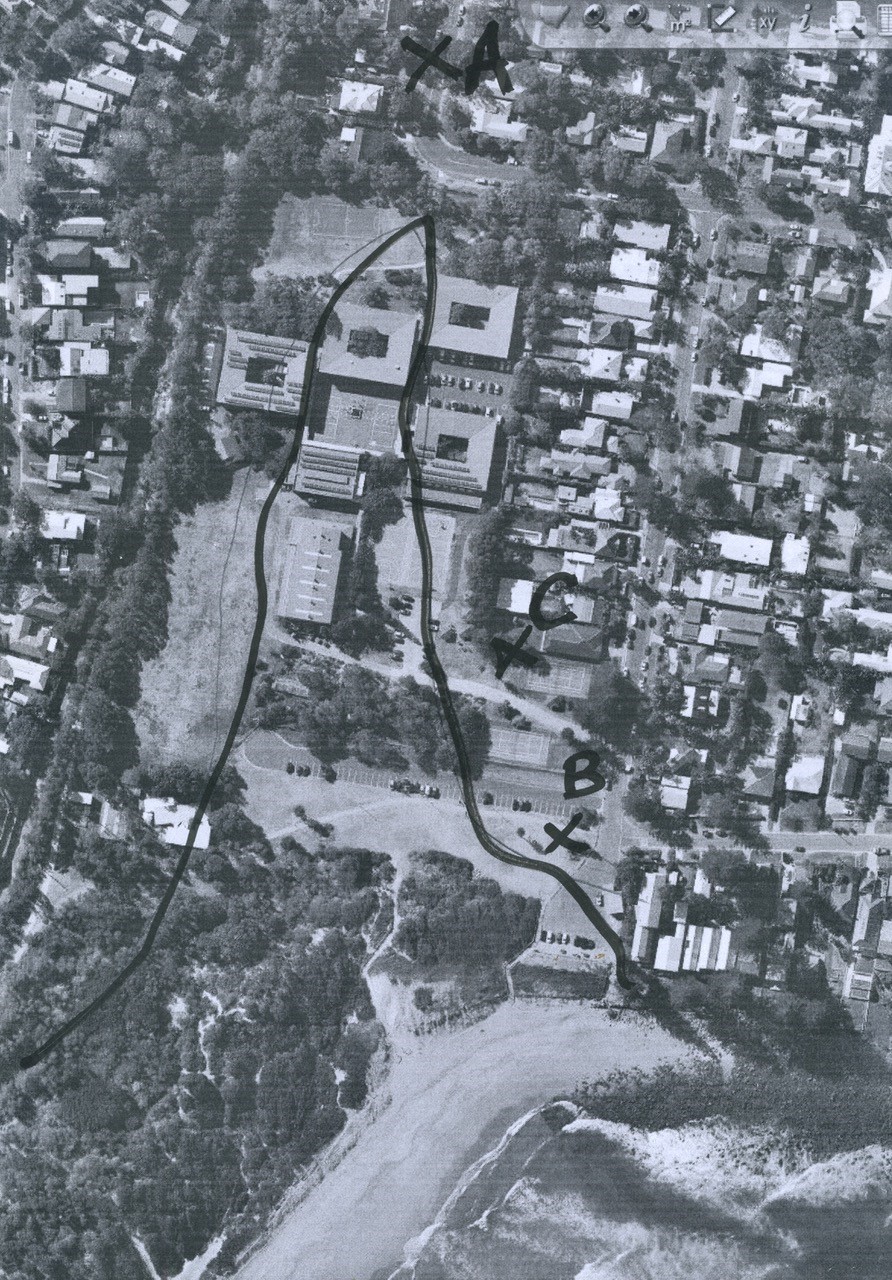

C and B: This might make it simpler or totally confusing! C is approx.. where the raft was photographed looking towards the top of the scan. B is where the dune would be at its tallest and again looking towards the top of the scan. A is where the photographer would have stood to take the pic looking back towards the North Av car park/dune with the northern end of the dune in the right of pic.

Here are 2 pics which have written Dale Kentwell’s name on the back! Not sure if they came from you and I thought you said they came from an album with AB pics in it.

The first one looks as though you are looking along the line of the dune with the imaginary raft off to the right. Sure the dune is taller in this one but probably because the pic is being taken closer to the North Av (carpark!) looking away along to the north west??

Number 2 could have been taken towards the end of the dune looking back towards the later car park area with the beach behind the distant dune?

The whole of the Avalon Beach valley flows towards and into Careel Bay. The council's aspirational plans for Careel Creek in the Avalon Place Plan, along with recent weeks of rains showing where the old creeks and drainage lines once flowed.

Arthur Jabez Small, who subdivided so much of Avalon into suburban blocks, recommended culverts and drainage at the south end of the beach from early on.

In the Avalon Beach shopping area Warringah Shire council's Minutes of Meetings record an insight into a problem that still hadn't been fixed:

30/4/1928: 40.,Garland, Seaborn & Abbott 13/4/28 Suggesting certain drainage improvements at Avalon Beach to prevent damage to A J Small's property. Resolved Crs. Hitchcock, That the Engineer furnish an estimate of the cost, and the work of cutting the drain be put in hand immediately the transfer is finalised.

62. Garland. Seaborn & Abbott. 29/6/28. Again requesting that the Shire Engineer confer with the green-keeper of Avalon Beach golf links in regard to defective drainage. Referred to the Overseer for attention.

18. Main Roads Board. 16/7/28. Advising that the length of Barrenjoey Road which is proposed to be proclaimed a main road is that extending from Newport to the end of the last at deviation at Avalon. Resolved: (Crs. Hitchcock, Atkins) - That an application be made to have the whole length of Barrenjoey Road proclaimed a main road. 20. H.E. Fry. 12/7/28. Requesting a garage approach to 57, Avalon Beach Estate. Referred to the Overseer for report.

23/7/1928: 45. Garland. Seaborn & Abbott. 10/7/28. Suggesting, as a temporary measure to relieve the drainage trouble at Avalon Beach, that a drain be cut from the junction of Barrenjoey Road deviation and Avalon Parade to the 25-ft.easement opposite the tennis courts. Left with the Engineer to deal with

By May 1934 the following ran in the NSW Gazette:

Department of Public Health,

Sydney, 23rd May, 1934.

PUBLIC HEALTH ACT; 1902, SECTION 55.

Unhealthy building land at Avalon, fronting Barrenjoey-road, Old Barrenjoey road, Avalon-parade and Central-road, Shire of Warringah.

THE Board of Health have reported that after due inquiry, they are of opinion that it would be prejudicial to health it certain land situated in the Shire of Warringah, and described in Schedules hereunder, were built upon in its present condition.

The Board of Health hare further reported that in order to render such land fit to be built upon it is necessary that:—

(a) the land be drained by properly constructed stormwater channels of capacity sufficient to carry off all water passing over the area;

(b) The surface of the land comprised in Schedule 1 be raised with clean soil or sand to conform to the following grades—

1. at Barrenjoey-road and Old Barrenjoey road to the height of the adjacent crown of those roads, rising therefrom on a grade of one in 100;

2. at the drainage easement or lane to a height 3 inches above the natural surface of the land, rising therefrom on a grade of one in 100;

(c) the surface of the land comprised in Schedule 2 be raised with clean soil or sand at the watercourse to a height 3 inches above the natural surface, rising therefrom on a grade of one in 100;

(d) all floors be laid 011 joists, the undersides of which shall be not less than 18 inches above the surface of the land when raised;

(e) the whole of the work be done to the satisfaction of the Board of Health.

Now, therefore, in pursuance of the power and authority vested in me by section 55 (1) of the Public Health Act, 1902, I hereby declare that such land shall not be built upon until the measures above referred to which are also specified in a document deposited in the office of the Local Authority (the Council of the Shire of Warringah) and open to, the inspection of any person, have been complied with, or until this notice has been revoked by me.

R. W. D. WEAVER, Minister for Health.

Schedule No. 1.

Commencing at a point 011 the north-western side of Old Barrenjoey road, being the southernmost corner of lot 10, d.p. 9,151; and bounded thence 011 the south-west by the south-western boundary of Jot 10 north-westerly to lane; thence by that lane north-easterly to Avalon-parade; thence by a line north-easterly to the westernmost corner of lot 13; thenee by lane north-easterly to the northernmost corner of lot 20; thence by part of the north-eastern boundary of lot 20 south-easterly to a point 135 feet along that boundary north-westerly from Barrenjoey-road; thence by a line north-easterly to a point on the south-western boundary of lot 22, being 70 feet along that boundary from Barrenjoey-road thence by that boundary south-easterly to Barrenjoey Road; thence by lines bearing consecutively 37 degrees 185 feet, 47 degrees 310 feet, 122 degrees 125 feet, 189 degrees 250 feet, 196 degrees 0*50 feet; thence by a line southwesterly to the easternmost corner of lot*8, d.p. 13,975; thence by the south-eastern and south-western boundaries of lot 8 to the westernmost corner of lot 8; thence by a line south-westerly to the southernmost corner of lot 13, d.p. 12,047; thence by lane south-westerly to the*southernmost corner of lot "21; thence by the south-western boundary of lot 21 north-westerly' to Old Barrenjoey road; thence by Old Barren joey road north-easterly to the westernmost corner of lot 13; thence by a line northwesterly, to the point of commencement.

Schedule No. 2.

Commencing at a point on the north-eastern side of Avalon-parade, being the westernmost corner of lot 33, d.p. 9,151; and bounded thence on the soutli-west by Avalon-parade north-westerly to the westernmost corner of lot 52; thence by the north-western boundary of lot 52 north-easterly 80 feet; thence by a line parallel to Avalon-parade north-westerly to the south-eastern boundary of lot 60; thence by a line north-westerly to the north-western boundary of lot 66, beings point 190 feet north-easterly along that boundary from Avalon-parade; thence by that boundary north-easterly 430 feet; thence by a line south-easterly to the south-eastern boundary of lot 37, being a point 30 feet north-easterly from the southernmost corner of lot 37; thence by a line parallel to the south-western boundary of lot 36 south-easterly to the south-eastern boundary of lot 34; thence by a line south-easterly to the southernmost corner of lot 33; thence by a line bearing 116 degrees 160 feet; and by a line north-easterly to the northernmost corner of lot 20; thence by lane south-westerly, to the point of commencement. PUBLIC HEALTH ACT, 1902, SECTION 55. (1934, May 25). Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales (Sydney, NSW : 1901 - 2001), p. 2030. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article223060059

This state of flooding still persists today, even with the creeks that thread through the valley placed in pipes, and Careel Creek in the most noticeable open drain that still runs alongside the Reserve, that will still overflow into the green areas alongside it, and even onto the homes built backing on to the same.

When the reserve was used for camping people living there permanently during the 1930's, due to the economic depression, and after World War Two, due to a lack of materials to build new homes with. Permanent residents recalled their possessions and even the people being washed right along Careel creek; some even stating they were washed out into Careel Bay.

A few examples:

THEY SUFFERED DISCOMFORT FROM THE RAIN: Mr. Syd Forrester, of Leichhardt, digging a trench during heavy rain in an effort to prevent the flooding of his tent at the Avalon camping ground yesterday.

The occupants of six of the 90 tents on the reserve left for home. THEY SUFFERED DISCOMFORT FROM THE RAIN. (1948, January 15). The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 3. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article18057497

Freak Storm Hits Avalon: Drives Out Tent Dwellers

A freak hailstorm yesterday flooded many parts of Avalon, doing hundreds of pounds' worth of damage. Scores of people living in the camping area at Avalon were forced to leave their bornes. Tents were torn to-shreds and the roofs of caravans severely damaged. Several tents and the furniture inside them were washed out to sea by floodwaters. Most of the families living in the camping area were given shelter for the night in the Avalon surf shed.

Mrs. Joyce Andries, of the Avalon Fire Station, said last night that immediately residents realised the floodwaters were rising, volunteers raced to the camping area to help to evacuate the children. The children were carried to safety through the racing water. Most of them were taken to the Avalon surf sheds, and the remainder were taken to the homes of relatives and friends.

Among the worst sufferers in the camping area were Mr. and Mrs. V. Harrington, who estimated their losses at about £.250. Their tent was not washed away, but damage to the roofing, sides and floor coverings was "enormous," said Mr. Harrington. The roof of Harrington’s tent was torn to shreds by the hailstones while water roared over the floor, destroying floor coverings and food supplies. Mr. Harrington had to use a suction pump to clear the water from the tent. He said he had only just cleaned up and repaired the damage done by last Saturday morning's floods. The storm began shortly after 2 p.m. and lasted for nearly three and a half hours.

Hailstones, measuring almost two and a half inches across, rained on the shopping and camping centres. Stormwater, in places three feet deep, raced through the shopping centre, flooding shops and homes. Hundreds of pounds' worth of stock in the shops was destroyed. Road traffic from Palm Beach and Sydney was dislocated. Vehicles were unable to pass Avalon.

The tent on the left, owned by Mr D. Needham, was completely capsized by the rushing waters.

One of the shops which suffered most damage was Le Clercq's general merchandise store in Avalon Parade. Mr. Le Clercq, the owner, bored holes in the floorboards in an attempt to drain away the two feet of water which was damaging his goods.

He said he had only just cleaned up the debris from a flood which occurred on Friday. He had suffered more than £250 worth of damage in that flood.

The rush of water through Avalon Parade was so great at one stage that several cars were almost submerged. The swirling flood carried one car almost 200 yards before dumping it on the pavement.

Freak Storm Hits Avalon: Drives Out Tent Dwellers. (1953, May 7). The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 1. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article18372783

Careel Creek alongside Avalon Beach Reserve in March 8, 2022:

Mrs Matilda (May) Metcalf, an Avalon Beach resident during Summer holidays who would later move there permanently. A sample from Council's minutes from before and during WWII shows hers was a block of land that was alongside the creek that wended from the far end of the flat at Avalon Beach (Dunbar Park) to Careel Creek. Although she was clearly a community focused person there were ongoing problems her correspondence indicates she attributed to the installation of pipes by the Council:

Mrs. M. Metcalf. 3/1/25 requesting approval to the alteration of the site of the 20-ft. lane on the n. side of her property, Lot 21, to the s. side of lot 20, Clareville Ocean Beach Estate, Avalon : Referred to the Engineer.

Avalon Flat Drainage: Mrs. M. Metcalf, 11/9/36, further re drainage at Avalon Beach, requesting a copy of an alleged agreement between the Council and herself in 1931, whereby she accepted the sum of £25 as compensation on the condition that the Council abate the nuisance. Resolved, - That information regarding the alleged agreement be supplied at the next meeting of the Council.

Water Conservation & Irrigation Commission, 21/8/39, further in regard to the Council's action in constructing a diversion channel offtaking from an unnamed watercourse in Avalon Park, Avalon and replying that the name of the complainant in the matter is Drainage Mrs. M. Metcalf. Resolved, - That the Commission be informed the Council does not desire to proceed with its application for a license under the Water Act, and that the mouth of the diversion channel be closed for about 5 yards, as recommended by the Engineer.

Mrs, I.M.Watermen, 24/10/40, inquiring whether Mrs. Metcalf has the Council's permission to close the lane adjacent to her place and convert it to her own use pointing out that this lane provides a short cut to Avalon beach for a number of the residents. Resolved, - That the Works Committee make an inspection and report to next meeting. (Crs.Campbell, Bathe) 18. Mrs. M. Metcalf, inquiring whether council proposes to proceed with repairs to the bridge across the water channel on her land, the bridge being in a dangerous condition. Resolved, That Mrs. Metcalf be asked on what grounds she makes her request.

Mrs. I.E..Waterman, 7/3/41, again complaining of obstruction of lane at Avalon, and stating that from what she can gather, the person responsible for the obstructions is determined to give the Council as much trouble as possible. Resolved - That Mrs. Metcalf be requested to expedite the removal of the obstructions in accordance with a promise which she made to the Works Committee.

S. C. Taperell, Solicitor, 15/4/42, an behalf of Mrs. K. Metcalf, of Avalon, advising that censiderable damage was done to his client's land at Avalon by the negligence of the Council in connection-with certain channels and drains on and about the land of his client and adjoining land, and requesting that the Council make an adequate offer of compensation in respect of such damage. Resolved, - That the matter be referred to the Insurance Company.

S. C. Taperell. Solicitor, 13/5/42, giving notice of intended District Court action against the Council for compensation for alleged damage to property at Barrenjoey Road, Avalon owned by Mrs. M. Metcalf, by Council's drainage system: The Shire Clerk reported that a copy had been sent to the Insurance Company for attention under the Public Risk policy, and the letter was 'received'.

Mrs.M. Metcalf, 28/5/43, reporting that the bridges on her property at Avalon Beach are dangerous, and enquiring if Council can help her in the matter, Resolved, -That a letter be sent to Mrs. Metcalf stating Council would like to help her but as the bridges are on private property it is unable to comply with her request.

Mrs. M. Metcalf, 6/6/46, drawing attention to the failure of the constructed drain on Council's property at Avalon to carry away flood waters, and that six pipes are concentrating the water into the creek through her property. Resolved, She be informed of the Engineer's report that this land is very low-lying and would fill with ordinary rain without any overflow from Council's drain.

Marshall, Marks & Jones 9/12/47 saying that as no reply. as been received to their letter Re; Mrs. Metcalf, she has been instructed to call for tenders and have the necessary work done, and that the Council will be looked to for payment for such work. Resolved: That the blackberries be removed from the footpath and the Solicitors informed that the Works Committee could find no trace of damage to the fence when an inspection was made.

A few other insights in Mrs M. Metcalf provide that she was appointed an Honorary Ranger in 1944 under the Birds and Animals Protection Act, and:

DISTRICT COURT.

(Before Judge While.)

ACTION AGAINST COUNCIL.

The hearing was continued of the action In which May Metcalf of Oxford-street, Woollahara, sued the Warringah Shire Council for £.160 damages for alleged faulty construction of roads and drains, which resulted in the flooding of her garden at 'St Jerome' Barrenjoey-road Avalon. The defendant council denied negligence, and pleaded contributory negligence and waiver by plaintiff. Judgment was reserved. Mr Howard Beale (instructed by Mr David Campbell) appeared for plaintiff, and Mr Bryan Cruller (Instructed by Messrs Dawson, Waldron, Edwards, and Nicholas) for defendant council. DISTRICT COURT. (1934, June 1). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 7. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article17067952

COTTAGES

photo: Government Printing Office d1_45760 - Avalon [From NSW Government Printer series: Government. Insurance.] Contents Date Range 01-01-1948 to 31-12-1948

Department of Public Health, Sydney, 23rd May, 1934.

PUBLIC HEALTH ACT; 1902, SECTION 55.

Unhealthy building land at Avalon, fronting Barrenjoey-road, Old Barrenjoey road, Avalon-parade and Central-road, Shire of Warringah.

THE Board of Health have reported that after due inquiry, they are of opinion that it would be prejudicial to health it certain land situated in the Shire of Warringah, and described in Schedules hereunder, were built up on in its present condition.

The Board of Health hare further reported that in order to render such land fit to be built upon it is necessary that:—

(a) the land be drained by properly constructed storms water channels of capacity sufficient to carry off all water passing over the area;

(b) The surface of the land comprised in Schedule be raised with clean soil or sand to conform to the following grades—

1. at Barren joey-road and Old Barrenjoey road to the height of the adjacent crown of those roads, rising therefrom 011 a grade of one in 100;

2. at the drainage easement or lane to a height 3 inches above the natural surface of the land, rising therefrom on a grade of one in 100;

(c) the surface of the land comprised in Schedule 2 be raised with clean soil or sand at the watercourse to a height 3 inches above the natural surface, rising therefrom on a grade of one in 100;

(d) all floors be laid on joists, the undersides of which shall be not less than 18 inches above the surface of the land when raised;

(e) the whole of the work be done to the satisfaction of the Board of Health.

Now, therefore, in pursuance of the power and authority vested in me by section 55 (1) of the Public Health Act, 1902, I hereby declare that such land shall not be built upon until the measures above referred to which are also specified in a document deposited in the office of the Local Authority (the Council of the Shire of Warringah) and open to, the inspection of any person, have been complied with, or until this notice has been revoked by me.

R. W. D. WEAVER, Minister for Health.

Schedule No. 1.

Commencing at a point of the north-western side of Old Barrenjoey road, being the southernmost corner of lot 10, d.p. 9,151; and bounded thence on the south-west by the south-western boundary of Jot 10 north-westerly to lane; thence by that lane north-easterly to Avalon-parade; thence by a line north-easterly to the westernmost corner of lot 13; thence by lane north-easterly to the northernmost corner of lot 20; thence by part of the north-eastern boundary of lot 20 south-easterly to a point 135 feet along that boundary north-westerly from Barrenjoey-road; thence by a line north-easterly to a point on the south-western boundary of lot 22, being 70 feet along that boundary from Barrenjoey-road; thence by that boundary south-easterly to Barrenjoey-road; thence by lines bearing consecutively 37 degrees 185 feet, 47 degrees 310 feet, 122 degrees 125 feet, 189 degrees 250 feet, 196 degrees 0*50 feet; thence by a line southwesterly to the easternmost corner of lot*8, d.p. 13,975; thence by the south-eastern and south-western boundaries of lot 8 to the westernmost corner of lot 8; thence by a line south-westerly to the southernmost corner of lot 13, d.p. 12,047; thence by lane south-westerly to the*southernmost corner of lot "21; thence by the south-western boundary of lot 21 north-westerly' to Old Barrenjoey road; thence by Old Barrenjoey road north-easterly to the westernmost corner of lot 13; thence by a line northwesterly, to the point of commencement.

Schedule No. 2.

Commencing at a point on the north-eastern side of Avalon-parade, being the westernmost corner of lot 33, d.p. 9,151; and bounded thence on the south-west by Avalon-parade north-westerly to the westernmost corner of lot 52; thence by the north-western boundary of lot 52 north-easterly 80 feet; thence by a line parallel to Avalon-parade north-westerly to the south-eastern boundary of lot 60; thence by a line north-westerly to the north-western boundary of lot 66, beings point 190 feet north-easterly along that boundary from Avalon-parade; thence by that boundary north-easterly 430 feet; thence by a line south-easterly to the south-eastern boundary of lot 37, being a point 30 feet north-easterly from the southernmost corner of lot 37; thence by a line parallel to the south-western boundary of lot 36 south-easterly to the south-eastern boundary of lot 34; thence by a line south-easterly to the southernmost corner of lot 33; thence by a line bearing 116 degrees 160 feet; and by a line north-easterly to the northernmost corner of lot 20; thence by lane south-westerly, to the point of commencement. PUBLIC HEALTH ACT, 1902, SECTION 55. (1934, May 25). Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales (Sydney, NSW : 1901 - 2001), p. 2030. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article223060059

Department of Public Health, Sydney, 11th January, 1935.

PUBLIC HEALTH ACT, 1902, SECTION 55.

Unhealthy building land at Avalon, fronting Barrenjoey-road, Old Barrenjoey road, Avalon-parade and Central-road, Shire of Warringah.

IN pursuance of the provisions of the Public Health Act, 1902, I hereby notify that I have amended in the following manner, the notice regarding the abovementioned land published in the issue of the Government Gazette No. 97 of 25th May, 1934:—

By the deletion of the following words contained in Schedule No. 1:—

thence by a line south-westerly to the easternmost corner of lot 8, d.p. 13,975; thence by the south-eastern and south-western boundaries of lot 8 to the westernmost corner of lot 8; thence by a line south-westerly to the southernmost corner of lot 13, d.p. 12,047;

and the substitution therefor of the following words:—

thence by a line westerly to a point on the south eastern boundary of drainage reserve, being 125 feet north-easterlv along that boundary from Avalon-parade; thence by that drainage reserve south-westerly to Avalon-parade; thence by a line south-westerly to the northernmost corner of lot 10; Whence by the north-western boundaries of lots 10 and 11 and the south-western boundary of lot( 11 south-westerly and southeasterly to lane.

__ R. W. D. WEAVER, Minister for Health. PUBLIC HEALTH ACT, 1902, SECTION 55. (1935, January 18). Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales (Sydney, NSW : 1901 - 2001), p. 273. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article224745510

When it rains these water flows through the land and old creek would flood the flat area. Avalon camping ground campers, established in the early 1930's beside Careel Creek and behind the Avalon Beach dunes, was often the site of flooded tents with residents recalling even into the 1950's seeing people catching 'floaties' along the creek to Careel Bay and the surf life saving clubhouse being called into duty to house those who suddenly found themselves without any shelter in the middle of the night.

Careel Creek Bridge-Cement Channel-way going in, and roadway being changed heading north to Palm Beach:

TRANSPORT (DIVISION OF FUNCTIONS) ACT, 1932.

MAIN ROADS ACT, 1924-1936.

PROCLAMATION.

(L.S.)

WAKEHURST, :Governor.

I, the Eight Honourable John de Vere, Baron Wakehurst, Governor of the State of New South Wales, in the Commonwealth of Australia, with the advice of the Executive Council, and by virtue of the provisions of the Transport (Division of Functions) Act, 1932, and in pursuance of the provisions of the Main Roads Act, 1924-1936, do by this my Proclamation declare that so much of the land hereunder described as is Crown land is hereby appropriated, and so much thereof as is private property is hereby resumed under the provisions of the Public Works Act, 1912, for the purposes of the Main Roads Act, 1924-1936, and that the land hereunder described is hereby vested in the Commissioner for Main Roads, and I hereby further, declare the land hereunder described to be a public road, and, in accordance with a recommendation of the Commissioner for Main Roads, the said land is hereby placed under the control of the Council of the Shire of Warringah.

Signed and sealed at Sydney, this twenty-sixth day of May, 1937.

By His Excellency's Command,

B. S. STEVENS.

GOD SAVE THE KING!

Description of the Land referred to.

All that piece or parcel of land situate in the Shire of Warringah, parish of Narrabeen, county of Cumberland and State of New South Wales, being part of lots 11 to 16 inclusive, deposited plan 14,883: Commencing at a point on a north-western side of Barrenjoey-road being the southernmost corner of lot 11, deposited plan 14,883 aforesaid; and bounded thence on the south-west by part of the south-western boundary of that lot bearing 318 degrees 50 minutes 14 feet 9£ inches: thence on the north-west by a marked line bearing 29 degrees 43 minutes 397 feet 9 1/2 inches to the high-water mark of Careel Creek; thence on the east by part of the highwater mark of that creek generally south-easterly to the north-western side of Barrenjoey-road aforesaid; thence on the south-east by part of that side of that road being lines bearing 235 degrees 35 minutes 261 feet 5 1/2 inches and 209 degrees 43 minutes 22 feet, to the point of commencement,—having an area of 2 roods 21 1-10th perches or thereabouts, and paid to be in the possession of A. J. Trunt, (Mrs.) E, Walshaw, H. C. Price, (Miss) N. Fillars, L. West and A. Walshaw.

Also, all that piece or parcel of land situate in the Shire of Warringah, parish of Narrabeen, county of Cumberland and State of New South Wales, being part of the land in Certificate of Title, register volume 3,847, folio 56 and part of the 100-ft. reservation adjoining: Commencing at a point on the high-water mark of Careel Creek bearing and distant 29 degrees 43 minutes 30 feet 9| inches from the northernmost corner of the firstly described parcel of land; and bounded thence on the north-west, west and south-west by marked lines bearing consecutively 29 degrees 43 minutes 33 feet, 26 degrees 34 minutes 40 seconds 71 feet 6} inches, 20 degrees 18 minutes 71 feet 6 1/2 inches, 14 degrees 1 minute 10 seconds 71 feet 6£ inches, 7 degrees 44 minutes 30 seconds 71 feet 6 J inches, 1 degree 27 minutes 50 seconds 71 feet 6j inches, 355 degrees 11 minutes 71 -feet 6£ inches, 348 degrees 54 minutes 20 seconds 71 feet 6£ inches, 342 degrees 37 minutes 40 seconds 71 feet 6 1/2 inches and 339 degrees 29 minutes 20 seconds 612 feet 7i inches to the south-eastern -side of a road 66 feet wide; thence again on the north-west by part of that side of that road bearing 62 degrees 40 minutes 14 feet li inches to a south-western side of Barrenjoey-road; thence on the north-east and east by parts of southwestern and western sides of that road bearing 159 degrees 29 minutes 20 seconds 724 feet and 174 degrees 58 minutes 40 seconds 409 feet 6| inches; thence on the south-east by marked lines bearing 282 degrees 20 minutes 50 seconds 11 feet Hi inches and 209 degrees 43 minutes 227 feet 6£ inches to the high-water mark of Careel Creek aforesaid; thence again on the south-west by the high-water mark of that creek generally north-westerly, to the point of commencement,—having an urea of 3 roods 29 9-10th perches or thereabouts, and said to he in the possession of the Council of the Shire of Warringah.

Also, all that piece or parcel of land situate in the Shire of Warringah, parish of Narrabeen, county of Cumberland and State of New South Wales, being part of the land in Certificate of Title, register volume 3,847, folio 56: Commencing at the intersection of a southwestern side of Barrenjoey-road with the north-western side of a road 66 feet wide bearing 339 degrees 29 minutes 20 seconds and distant 66 feet 5| inches from the northernmost corner of the secondly described parcel of land; and bounded thence on the south-east by part of the north-western side of the road 66 feet wide aforesaid bearing 242 degrees 40 minutes 14 feet li inches; thence on the south-west by marked lines bearing consecutively 339 degrees 29 minutes 20 seconds 596 feet 11 1/2 inches, 337 degrees 11 minutes 20 seconds 76 feet 5f inches, 332 degrees 35 minutes 30 seconds 76 feet 5£ inches, 327 degrees 59 minutes 40 seconds 76 feet 5f inches, 323 degrees 23 minutes 50 seconds 76 feet 5 1/2 inches, 318 degrees 48 minutes 76 feet 5| inches and 316 degrees 30 minutes 422 feet 2f inches to the south-eastern side of a road 66 feet wide; thence on the north-west by part of that side of that road bearing 62 degrees 40 minutes 14 feet 7 inches to the southwestern side of Barrenjoey-road aforesaid; thence on the north-east by parts of south-western sides of that road bearing 136 degrees 30 minutes 634 feet 9f inches and 3.19 degrees 29 minutes 20 seconds 791 feet 10£ inches, to the point of commencement,—having an area of 2 roods 2 3-10th perches or thereabouts, and said to be in the possession of the Council of the Shire of Warringah.

And also, all that piece or parcel of land situate in the Shire of Warringah, parish of Narrabeen, county of Cumberland and State of New South Wales, being part of a road 66 feet wide: Commencing at a point on a south-western side of Barrenjoey-road being the easternmost corner of the thirdly described parcel of land; and bounded thence on the north-east by part of that side of that road bearing 159 degrees 29 minutes 20 seconds 66 feet 5| inches; thence on the south-east by part of the south-eastern side of the road 66 feet wide aforesaid bearing 242 degrees 40 minutes 14 feet li inches; thence on the south-west by a marked line bearing 339 degrees 29 minutes 20 seconds 66 feet 5| inches; thence on the north-west by part of the north-western side of the road 66 feet wide aforesaid bearing 62 degrees 40 minutes 14 feet li inches, to the point of commencement,—having an area of 3 4-10th perches or thereabouts. (D.M.K. No. 479-1,171) (3634) TRANSPORT (DIVISION OF FUNCTIONS) ACT, 1932. (1937, June 4). Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales (Sydney, NSW : 1901 - 2001), p. 2129. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article224751674

Volume 3,847, folio 56 is the land donated by James Young and Robert Browning (Palm Beach Land Co - follow on from Barrenjoey Land Co.) to the then council and used as a tip, filling in what had been wetlands and a mangrove area, and later used for a tennis courts area, Hitchcock Park and the Careel Bay Soccer (Playing) fields - as well as being where the Careel Creek road bridge and concrete drainage pipe was placed with works completed on March 10 1938 - this concrete drainway/roadbridge is still in place:

'Careel Creek looking south' 10.3.1938 - and road being built/widened. Item: FL3663714, courtesy NSW Records and Archives

Same concrete drain/roadway bridge - May 2025 - looking south-east from track leading to tennis courts

.jpg?timestamp=1747794855081)

.jpg?timestamp=1747794893300)

.jpg?timestamp=1747795053160)

.jpg?timestamp=1747795122664)

.jpg?timestamp=1747795167692)

James Young was one of the original Directors of the Barranjoey Land Company, a relative of Mr. Wolstenholme, who was in turn a son of Maybanke Anderson. He was a barrister by profession, served as President of Ku-ring-gai Council at one time.

The Minutes of the Warringah Shire Council Meeting of 27th October,1924 state ''The President verbally reported having interviewed Mr. James Young and submitted a letter from Mr. Young, offering to sell his 10 ¾ acres at Careel Bay fronting Barrenjoey Road for £700 on terms, namely, £50 deposit, and the balance in annual instalments of £100 each with interest at 6 ½ % on unpaid purchase money. It was resolved, - (Crs. Hewitt, Hitchcock) That the offer be accepted and the terms approved, but that the President endeavour to arrange for a smaller deposit. ''

See: Careel Bay Playing Fields Reserve - Including Hitchcock Park: Birds, Boots & Beauty (History page)

These photos, taken in May 1974 by John Stone, shows Old Barrenjoey Rd in flood.

Photos courtesy John Stone and ABHS

Giles Stoddart of Avalon Honey:

I lost two of my colonies of bees when Careel Creek flooded in March 2022 during heavy rains and a king tide that meant there was nowhere for the rain to go except into people’s gardens and houses. I have a couple in North Avalon that host hives for me in their back garden, which backs on to Careel Creek. We had agreed on a location for the bees which was away from the house, and unfortunately the garden flooded very quickly before I could get there to move the hives. I was devastated and I tried to save the colony, but despite many thousands of bee surviving the flood and me giving them a new dry home with food, they never really became strong enough to survive the cooler Winter weather.

Avalon Honey's Giles trying to save his bees:

In May 2024 the valley of Avalon and Bilgola Plateau has been reminded this week that it was once a marshy floodplain called 'Priests' Flat' alongside the beach from Kamikazee corner to the mangroves of Careel Bay and that even though those water channels may now be funnelled into concrete pipes, they may still reappear during prolonged downpours of rain.

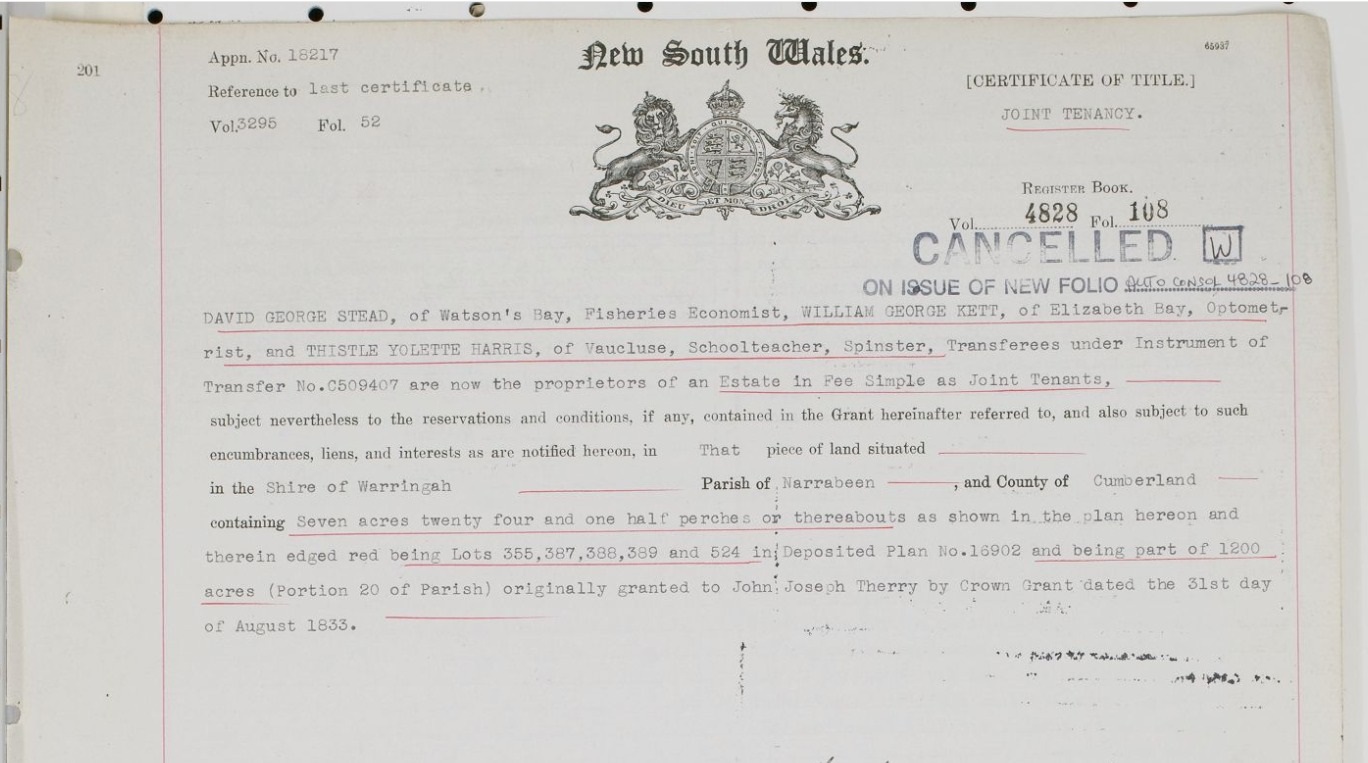

The NSW HRLV provides under Volume 4828, Folio 108 from when Angophora Reserve was handed to the community by A J Small - note the marked water courses, or creeks::

%20Vol%20Fol%204828-108.png?timestamp=1659822451523)

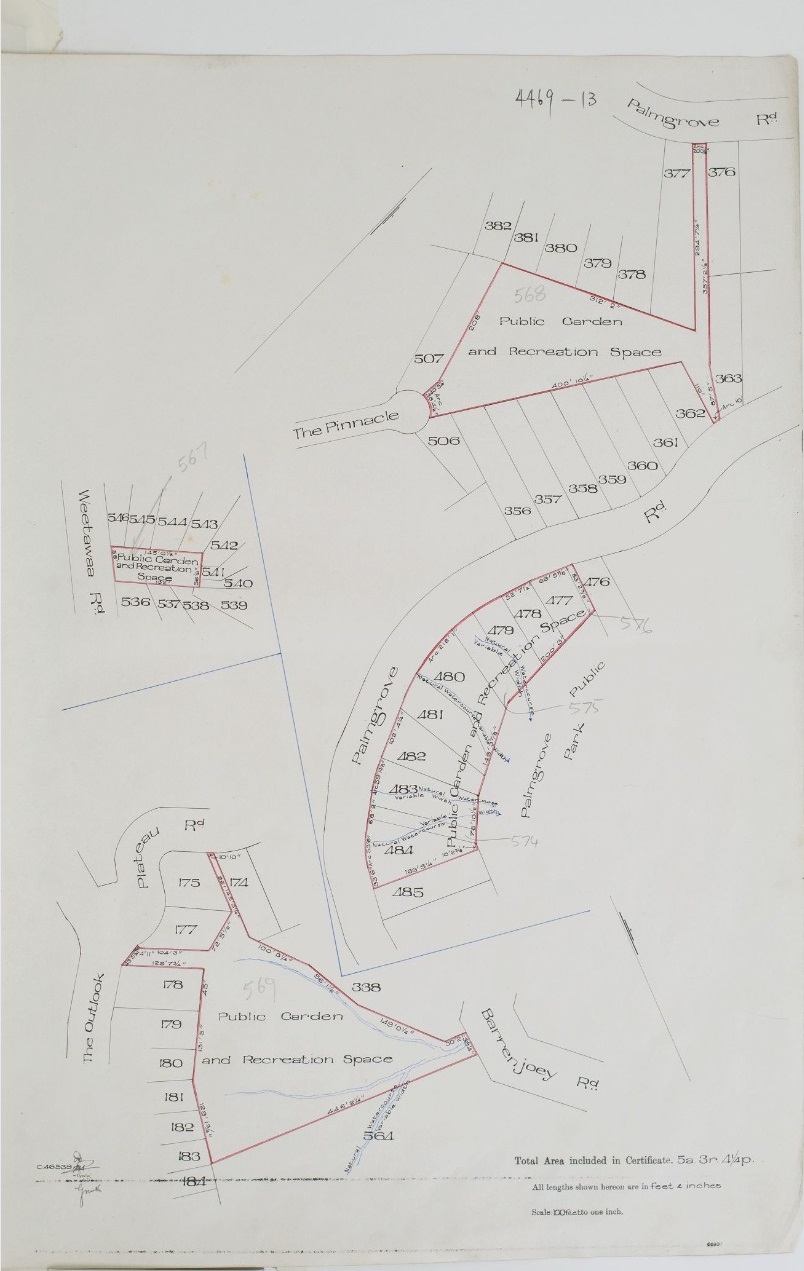

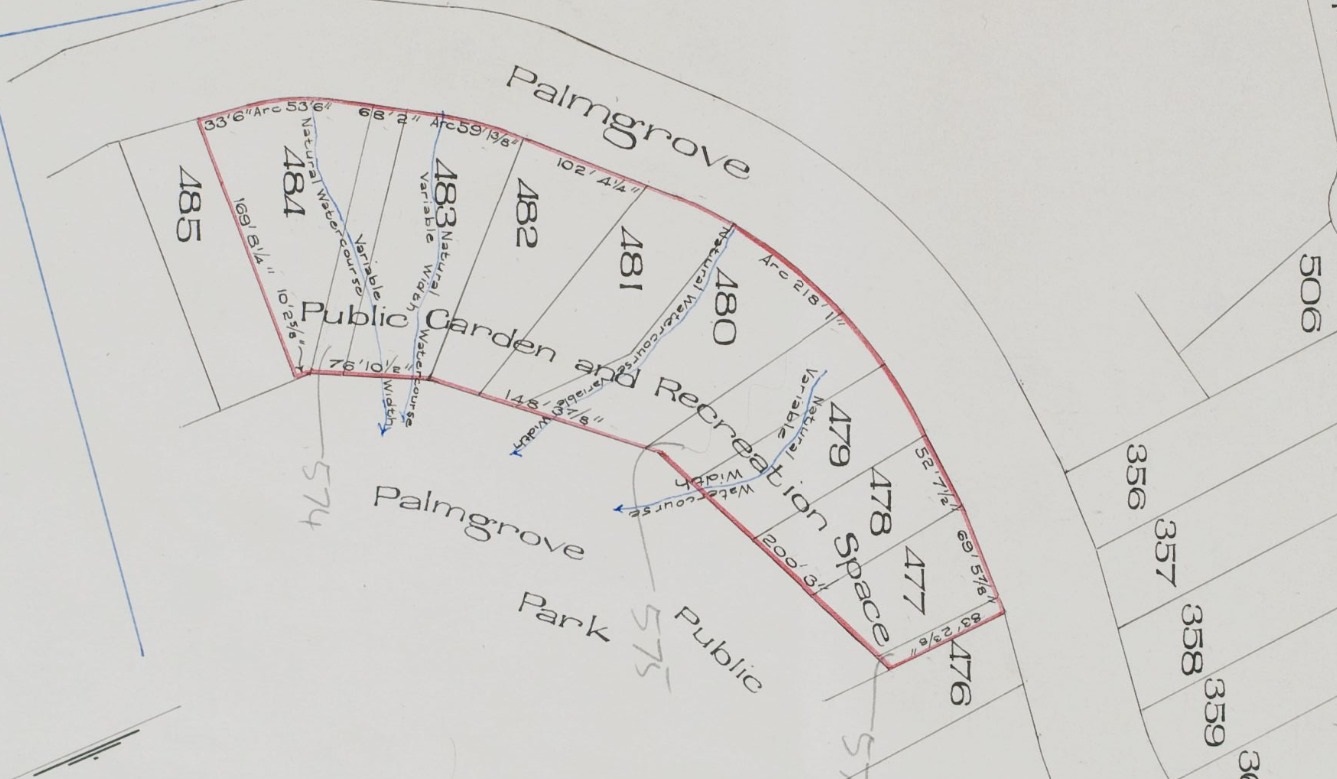

In February 1931 the formalisation of the dedicating the Bilgola Plateau parks from the same gentleman is recorded in Vol-Fol 4469-13, over 5 acres all up, which included some of the well-known Bilgola Plateau parks:

.jpg?timestamp=1714593544979)

.jpg?timestamp=1714594261697)

Note the creeks threading through these parks - the same is in the landscape at Angophora Reserve and Hudson Park (dedicated later as a public reserve, in 1957) during this era, as shown when that was formally gifted by A J Small and had the Wildlife Presrevation Society as Trustees, and in Dunbar Park, when that was gifted as well:

References - Extras

- Grand Old Tree Of Angophora Reserve Falls Back To The Earth

- Avalon Beach This Week: A Place Of A Bursting Main, Flooding Drains + Falling Boulders - May 2024

- John Collins of Avalon

- My Holiday by Charles de Boos – 1861

- Careel Bay Playing Fields Reserve - Including Hitchcock Park: Birds, Boots & Beauty (History page)