November 1 - 30, 2025: Issue 648

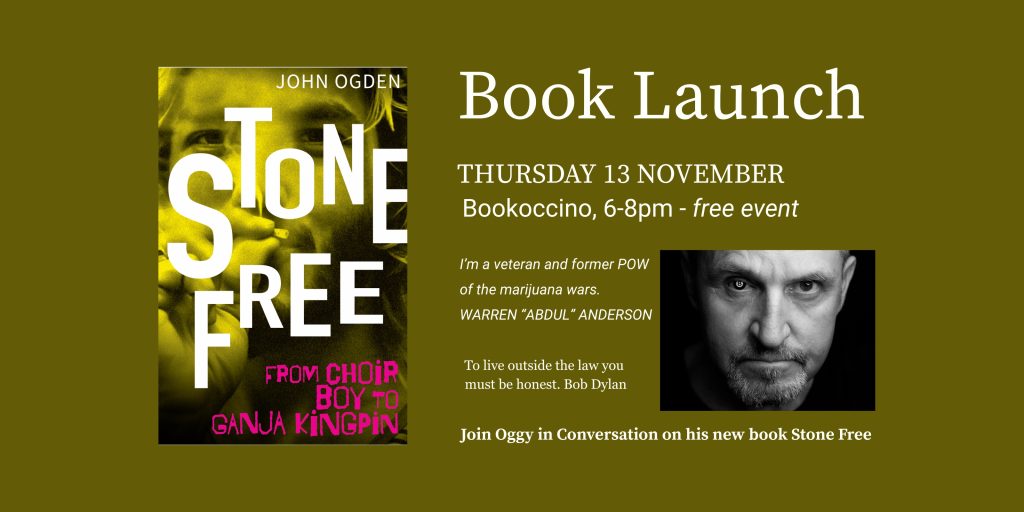

John Ogden's 10th Book 'Stone Free' Shares insights from a world much-changed

'Abdul' and 'Oggy', 2025.

John has published and helped with about 30 books since starting Cyclops Press in 1999.

Stone Free is his 10th book as an author, and my second biography, with the other called Whitewash — the story of Bernie Showery, an African-Australian who was a member of the Freshwater SLSC when Duke Kahanamoku stayed there in the summer of 1914-15. But most readers on the peninsula; would perhaps best know him by the Saltwater People companion books

Stone Free: From Choirboy to Ganja Kingpin, published through Cyclops Press, is available now at Bookoccino and Berkelouw Books.

The launch, a free event, takes place Thursday November 13 at Bookoccino with Nic Carroll MCing.

Stone Free: From Choir Boy to Ganja Kingpin unravels the true story of Warren Anderson.

Warren was a Californian misfit who turned his back on the American Dream. Reforged as James “Abdul” Monroe, he emerged from the psychedelic haze of the 1960s not as a compliant citizen but as an outlaw fugitive.

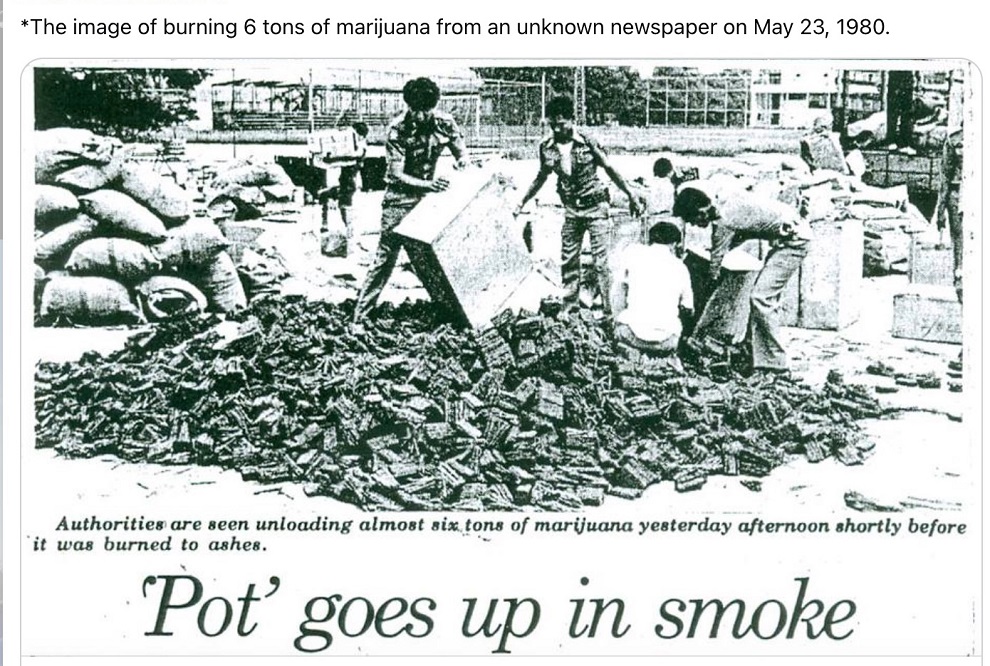

What began as a search for meaning morphed into one of the boldest Thai-stick marijuana smuggling operations of the later 20th century. But living untethered had a price.

Betrayed by a former friend and convicted on major conspiracy to import marijuana into America, Abul was shackled and shuffled through 25 federal prisons, doing time alongside outlaw ghosts like surfing’s dark prince, Miki Dora, and the infamous Stopwatch Gang serial bank robber, Paddy Mitchell.

Oggy recently shared a few insights into this new work.

You’ve published a few books now John, which number is this?

Stone Free is my 10th book as an author, and my second biography, with the other called Whitewash — the story of Bernie Showery, an African-Australian who was a member of the Freshwater SLSC when Duke Kahanamoku stayed there in the summer of 1914-15. But most readers on the northern beaches would perhaps best know me by the Saltwater People companion books.

Why did you embark on a biography this time?

While interviewing Abdul, I was entertained by some great storytelling, but when you break a voice down into text it sometimes isn’t enough. So I started looking around at what else had been going on I the zeitgeist around that period and that became part of the story.

I struggled for a while whether to do it as an autobiography or a biography, and even developed it as a film script. Then I started talking to other people who are part of the story. The DEA who busted him, for example, had a great back story, but if there was a villain in the book, then Abdul’s one time friend, Mike Boyum, would have a shot at the title. He is the leading nemesis and his parallel story converges for a dramatic finale.

These would provide context?

Absolutely, especially if it’s a young reader – even I wasn’t aware of how radical the hippy scene in California was in the mid-1960’s, and younger people would have little knowledge of that.

Some of the journey’s Abdul undertook were incredible. When travelling nowadays, you have mobile phones, the internet, and GPS, and travel doesn’t seem that hard. But back then, some of the feats he did were quite extraordinary;, like sailing a 16 t Hobie cat for 5 days and 5 nights in unchartered waters.

For those not familiar with Warren Anderson; who is he and how did you decide it was time to tell his story?

I first met Abdul in 1972. I think we were both on the run – I was escaping National Service for Vietnam and he was escaping the American Draft for the same conflict … plus a few other things. There were not too many surfers around in Bali in those days, perhaps around half a dozen and most of them Americans, so I’d go surfing with him. He’d bought a little property down on the beach at Legian when there was nothing there but coconut groves. He was a hippy with money, which always intrigued me as I never had two pennies to rub together. After that, I lost contact with him.

Then, about 3 years ago, I was editing the book Grajagan for Jack McCoy and Mike Ritter on the history of G-Land and Abdul’s name came up. Mike had also co-written a book with Peter Maguire called ‘Thai Stick: Surfers, Scammers, and the Untold Story of the Marijuana Trade’. It tells the whole of the Thai Stick marijuana trade and includes Abdul’s smuggling career. Through these books I gained more insights into what he’d been doing prior to when I met him. Before then he’d been smuggling hashish out of Kathmandu, but that all ceased because of a conflict between India and Pakistan. So in 1972, when I first met him in Bali, he was in between gigs. The Thai Stick thing started up in earnest a few years later, probably 1974. It became one of the most valuable contrabands in the world at that time.

Abdul in Bali, 1970's

Abdul was a true believer, who thought that by supplying quality marijuana and hashish to the world he was making it a better place. He sees himself as a kind of a bootlegger but with a product that didn’t have the dangers of alcohol

He wasn’t aware it can cause permanent psychosis in some people?

Well in those days, Thai Stick marijuana was the gold standard, but compared to today’s marijuana it wasn’t anywhere near as potent. I think it was around 36% THC whereas today you can get hydroponic weed with up to 99%, so in comparison the potential for damage can be much more severe now.

So you reconnected after you saw him spoken of in these other works?

Yes. I was promoting the Grajagan book and he came along to one of the launch nights, and as a pioneer at G-Land got up and spoke. I was listening to his stories and thought his journey would make a great book. Eventually he agreed … reluctantly.

How long has it taken for this project to reach a publish date?

Three years from when we first started talking about it and I started recording his different memories.

Three years is a big commitment – why was this subject so important, how is it part of what you’ve evolved through these works?

Well I’m in my 70 ‘s now and not getting any younger, so time is precious, but I had been working in that time in history on the Grajagan book and the Stephen Cooney memoir ‘‘Unearthed’’ – which you ran a story on a few years back. Stephen had been in the Morning of the Earth surf film and went there in 1971. So it was filling in some gaps in one way and also because of the personal connection with Abdul. So many aspects of the story intrigued me.

His mum was born and raised near Bondi beach. At age 16, she won a prize in the inaugural beach girl contest held at Bondi. The judge was Annette Kellerman. She married an American fighter pilot, who was based in Morotai, as was my father, so there were all these extra little connections. His uncle Fred was in the Bilgola surf club, and Fred’s daughter, Suellen, and her husband ran McDonald’s corner deli in Avalon (where the wine shop is now). His great-grandfather, George Joseph Malouf, owned about half of Redfern at the start of the 20th Century.

Stone Free offers a window into another era, when there were no mobiles to text mum, you’d send her an Aerogramme every 3 months to tell her you’re still alive.

It was a very different world to that we have today – less surveilled, no cameras everywhere, no tracking you via your phone or mining your data, or stalking you via social media, recording everything you do. It’s a period that no longer exists. Even the DEA agent who busted him, for example, said “I have no ill-feeling towards these guys, in another time they probably would have been CEO’s of companies.”

When Abdul went to Kathmandu, hashish and smoking it was legal, and had been for thousands of years. The two flash points of his Thai Stick smuggling career, Thailand and California, have now decriminalised the use of marijuana.

When and where is the launch for ‘Stone Free: From Choirboy to Ganja Kingpin’?

At Bookocino Thursday 13th of November at 6pm – Nic Carroll has kindly agreed to be MC.

If you can’t make that, it’s available now at Bookoccino, Berkelouws and on our Cyclops Press website.

Stone free to do what I please

Stone free to ride the breeze

Stone free I can't stay

I got to got to got to get away right now - Jimi Hendrix, Stone Free

A little more about the John Ogden from his 2013 Profile:

Where and when were you born?

I was born in Adelaide, South Australia in 1952.

What was that like, growing up there?

Australia in general was a bit of a cultural backwater in the early 1950’s and Adelaide seemed particularly remote. After a couple of years the family moved to Brighton Beach, on St Vincent Gulf, and that instigated my interest in and love affair with the ocean. In those low-tech days when I was a child I’d just go down to the beach and play.

When did you leave?

As soon as I finished school. I came from a fairly strict family and initially left home when I was about 16 and hitchhiked across to Victoria, to Torquay and the Great Ocean Road. I was there for about three months before I returned home. I then went back to school for a year before making my way up to the Northern Coast of New South Wales, living at Angourie for a while in 1971. At one stage I even worked in Manly on a building site as a brickies labourer, one of the hardest jobs I’ve ever had. It was at that stage that I saw this coastline for the very first time. I’d read about it in surf magazines –there weren’t a lot of surf magazines in the 1960’s, but they often wrote about this place – a lot of the world champions and surf heroes came from here. Adelaide is a pretty dry old place and to see sugar plantations and banana plantations along this coastline, it seemed like the most exotic place in the world. I put a memo in the back of my mind that I’d move here one day.

I actually worked for Tracks magazine in the 1970’s … by that stage I was living I Western Australia.

How did that come about – how did you get your first photo into Tracks?

Well, what happened was – after I’d come up here for a while I went back to South Australia and I’d been called up for Vietnam… it remains the only lottery I’ve ever won. I was a conscientious objector and so took off and went to Bali in early 1972, when I was 19, and was totally blown away by that experience. I was going to keep going and head off on the hippy trail through south-east Asia and across to London, but I didn’t have any money. I ended up going back to Adelaide and working in a Psychiatric Hospital for a year and a half as if you were working or studying you didn’t qualify for call-up. As it turned out I was in the last call-up before Gough Whitlam brought an end to our involvement in the Vietnam War. While working at the Psych Hospital I got my first 35mm camera - this was when I was about 20 – and started to get into photography seriously.

In 1973 I took off for good. I started working on tuna boats near Streaky Bay in South Australia.

After the first fishing season finished I spent that winter at Cactus in the Great Australian Bight. Some of my photos started percolating into Tracks and before long I was the west coast correspondent. A lot of those early photos from Cactus ended up in the Cactus book by Christo Reid. Eventually, I spent a few years in Indonesia and other parts of SE Asia in the early 1970s.

What was the first one [photo published]?

I can’t actually recall. It seems so long ago. It’s a long and involved story but I actually moved away from the coast for a while. I was in Thailand and Laos during the last days of the war in Vietnam and started working as a kind of freelance war photographer but I was a bit of a failure as a war photographer. I went to London to sell the photographs and lost the whole lot at the airport – they got stolen, my bag got stolen while I was in a phone box.

By this stage I was interested in film making. I had met Neil Davis while I was in south-east Asia … he was the famous Australian film photographer who shot all the Vietnam war footage we used to see on the news each night in the sixties. He’d inspired me to get into film-making … which is why I’d gone to London, to study filmmaking and sell some photos, but as I said, lost my portfolio and flew back to Western Australia in time to protest the sacking of the elected government by the queen’s representative. No revolution … but I began film studies there.

I ended up studying at a university in Western Australia and that’s when I go an official role at Tracks and became their contributing photographer for Western Australia.

I never had any flash telephoto lenses and you were never paid much money by surf mags so I used to do stories around the edges of surfing – I wasn’t the one chasing the latest surf contest – I was a bit of an old soul surfer, so I did a lot of peripheral stuff.

I never had any flash telephoto lenses and you were never paid much money by surf mags so I used to do stories around the edges of surfing – I wasn’t the one chasing the latest surf contest – I was a bit of an old soul surfer, so I did a lot of peripheral stuff.

What’s your favourite of the material you published then?

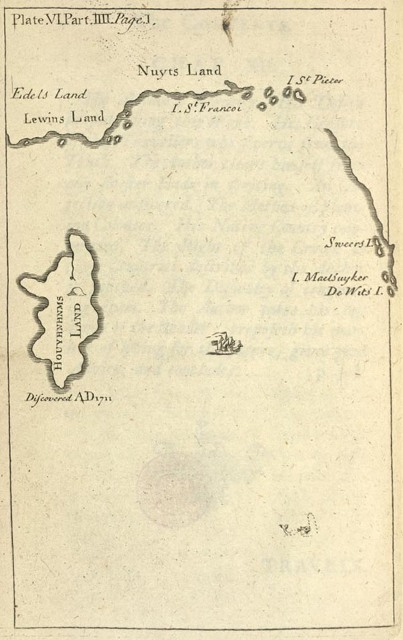

There’s one I did on Cactus that came out like I wanted it. I was studying literature at university as well as filmmaking and we were studying the works of Jonathon Swift. I realised that he had used some of the maps of the early Dutch explorers for the illustrations in Gullivers Travels. For ‘The Land of the Houyhnhnm’ chapter the map he used was taken from explorer charts of Nuyts Land - an island group off the coast from Cactus on the Great Australian Bight. I wrote a whole story about this fabled Land, a thin disguise for Cactus.

Right: Hermann Moll: Map of Houyhnhnms land, for the 1726 edition of Jonathan Swift's Lemuel Gulliver's travels into several remote nations of the world

That kind of style has carried through to your current works – to align or illuminate where these original texts meet real historical records and physical landscapes.

Yes – hadn’t thought of that before, but you’re right.

What was it like being involved in the surf industry then?

It was fun. Surfing was a relatively new sport then. Sounds like a Monty Python sketch, but growing up and going surfing in Adelaide in the early 1960’s we didn’t even have board shorts – we had to go to the army surplus shop and get a pair of old army shorts - and wetsuits were a woollen footy jumper with the arms cut off.

Adelaide winters are pretty bleak so it was tough work. Those early pre leg-rope days, with the short board revolution were pretty exciting. Young people were starting to get a bit of money and had cars – so the surf safari was a big part of the culture, and that branched out into travelling overseas to ‘discover’ places to surf.

Coming up here on the north coast of NSW in 1971 was brilliant. Angourie was uncrowded, and people like George Greenough were living in the area – we used to see him down there filming with this massive big water-housing strapped to his back while he was filming this point-of-view stuff for Innermost Limits of Pure Fun … a film I actually saw played during a Pink Floyd concert in Knebworth Manor in England in 1975. Above the band was a giant screen showing George Greenough’s footage from the NSW north coast with over 100,000 people watching. Apparently they’d done a music swap – he got the music rights and they got the image rights. That was kind of bizarre.

And then Morning of the Earth was shot around the time that I first went to Bali – so it was all happening. I was only a witness to it all … I hadn’t really got into photography at that stage.

Even in 1980, and even though I’d drifted away from surfing a little bit, to be on the North Shore after growing up with all the stories, and find myself out in the line-up with the water camera filming the Pipeline Masters – it was a buzz. Because you were there to record everyone else’s epic deeds you weren’t considered to be an enemy. They wanted you to get the shot, so apart from having to watch all the fun, it was great.

What was you first surfboard?

It was actually a toothpick that my dad made. After he finished his service in the war (WWII) he worked as a carpenter and there were new materials that were developed during the war, so he built one of those hollow marine ply boards. It was about 18 foot long, had a wooden frame with a skin of lacquered marine ply, and had a plug to let the water out. It was this massive thing … my friend Matthew Martin and I had to build a cradle out of bicycle wheels to get the bloody thing down the beach it was so heavy.

That was the starting point though – just to get out there in the waves on this bulky craft. Then Matthew got a cool-lite board and I somehow talked my dad into getting me a Malibu which was an old Ron plank - which I think used to be manufactured in Sydney in those days. It was a mongrel of a board but it was my first fibreglass surfboard.

I think dad always regretted building me that first board and then getting that second one because that was it – I was addicted. I didn’t get that office career he had in mind for me.

John Ogden - when younger.

Who was your favourite surfer to film?

In 1971 there was hardly anyone in Bali but by 1980 there were a few more – we had our own surfing crew. Peter McCabe and Rory Russell were the guys we were hanging out with mostly. Jerry Lopez was on the edges of that filming and Jerry had always been a bit of a hero of mine through being so strong at Pipeline.

When I actually went to Hawaii that was the reign of Mark Richards, who I never really got to know. I did befriend Buttons who I thought was a gifted surfer – just a natural. There was also Marvin Foster – they were the main guys I hung out with.

When or how did you end up back over on the east coast?

It took a while – I got married in Perth and had a baby. I left there around 1980 after finishing film school and got a job as water cameraman on a surf film. I went to Indonesia for six months and then Hawaii for the North Shore winter season and eventually ended up back here for the Australian part of the filming. Filming finished with the huge surf at the Bells 1981 contest, and following that I stayed in Victoria for 15 years. My real career started there … and I had another kid, Harley, while living there.

What did you do in Victoria for 15 years?

By that stage I’d finished film studies and didn’t really want to be a surf photographer as the money was so bad and I had a family to support and I grew sick of hanging around surf contests. There were a lot of pretentious surfers and hangers-on and it put me off. I wanted to make some serious films but ended up working on commercials. Eventually, I did work on a few documentaries and feature films – some of them pretty pivotal.

In the early 1980’s I spent a few years working on aboriginal documentaries and had some amazing experiences. One was called The Pintubi, which was a three by one-hour series based on the life of a man called Nosepeg Tjupurrulla. His story was quite incredible because the Pintubi lived in a very remote section of the Great Western Desert near the Western Australia border and a lot of them had never met or heard of Europeans until the 1950’s, when they were rounded up out of the Western desert so the British could test their atomic bombs.

Nosepeg’s first encounter with a European was with a man on a camel. He’d never seen either creature before. He thought it was a beast with two heads, and got such a shock he fell off a rock ledge and twisted his ankle. He ended up being put on the camel and taken to one of the welfare towns set up for the dispossessed Aborigines. There was another guy named 'Helicopter Tjungaroi' … you can imagine what his first contact was.

These guys were amazing and I spent months with them out in country in really remote parts – they took us to some incredible and quite sacred places. They’re all dead now so they were the last of their kind in that they had been fully immersed in the Dreamtime culture of Aboriginal Australia without contact with Europeans. There’s none like that anymore – so I was very privileged to meet these men and spend time with them.

There was another film ‘Triumph of the Nomads’ which was a three by one-hour series based on Geoffrey Blainey’s book. His book was basically making the point that Aborigines were doing very well before we came along – they weren’t the poor dying race that they are made out to be. At that time of first settlement many of the English and Irish convicts and settlers had been poor peasants, used staple foods consisting of one type of meat and two types of vegetables. The Aborigines had about 30 types of meat and the same amount again of vegetables. So they lived very well and the TV series mainly focused on that.

Another was called Peppimenarti which was about an Aboriginal run cattle station up in the top end. So they were quite good days, and it was good to make those authentic records.

Why were you attracted to our Aboriginal peoples as subjects for your documentaries?

The first time this really became active in my mind was when I was in London. I went to a party and because I had an Australian accent somebody accused me of being privy to the genocide of the Australian Aboriginal. Growing up in the 1950’s you didn’t learn anything about Aboriginal culture at school, it just wasn’t spoken about… but I think a lot of people had a quiet whispering in their hearts that something wrong had taken place, a great injustice. When this person accused me of being part of that, I actually felt quite dumb because I didn’t understand the issue. It startled me that there were people who knew more about my country than I did.

So when I went back and went to uni I made sure that I learnt what I could. I studied a couple of units of anthropology and one of these was six months studying traditional mythology and the sociology of Aboriginal culture, which was enlightening. I then did another six months dealing with post-contact legislation, which was incredibly heart-breaking. … and really frightening. It really shaped my sense that a great injustice had taken place.

I’d come from a family of Irish Catholics who had a strong sense of social justice, so by working on those docos – even though I didn’t actively go looking for them - I had come full circle. In 2006, after my mum died, I found out I have Irish convict heritage and probably have Aboriginal ancestry myself. The evidence is mainly anecdotal – I can’t find any paperwork and may never do so, but that doesn’t really matter. The interesting thing is that it could explain my strong sensitivity about Aboriginal culture.

I’ve always been interested in this … since returning from England in 1975. In 2008, after many years of research, I authored and published 'Portraits From a Land Without People' which raised $82,000 for the Jimmy Little Foundation’s work helping improve Aboriginal health. For the last 3 years I have been working with an Aboriginal men’s healing group called Gamarada, which meets every Monday night in Redfern.

What does 'Gamarada' mean?

I’m not sure what dialect it’s from … perhaps from Dharawal or Dharug … but it essentially means ‘comrade’. Gamarada provides a healing space for Aboriginal men. I can’t talk about it too much because it’s confidential – a lot of the men come from the justice system, and our work is built on trust.

As you’re probably aware, Aboriginal prisoners represent almost half of the prison population in some states, when they number only about 2% of the general population. There are very uncomfortable reasons for that- so Gamarada does a lot of work with these men to address the issues they’re facing – anger, healing and hopefully turn their lives around.

So the commercials were to fund the documentaries?

Not really – when I first started I was camera assistant, gaffer, grip … whatever was needed when making documentaries. In some of the dramatised segments I even had acting roles. I soon started to get work as a DOP (Director of Photography). It started with one of my first jobs which was a very low budget feature film called ‘As Time Goes By’ and it got I think four out of five stars on the Movie Show. All of a sudden my career was just about to take off … but at the same time, this was about 1986, the economy collapsed and there was no money available for filmmaking. Because I had a family and needed to put food on the table, and didn’t want to go back to camera assisting, I started shooting second unit on a TV series, Mission Impossible, up in Queensland. After that I started to get work on music videos and TV commercials … basically it just ballooned from there. Luckily I was good at what I did and ended up being very successful during that 15 years in Melbourne, which in turn financed my move to Sydney.

Working in film – what was your favourite – documentaries, film clips, commercials…?

I enjoyed them all. They were all different. Feature films were great because people take you seriously and you’re allowed to develop an extended bit of story making where people sit in the dark for an hour or two and allow you to create the world for them. Whereas with a television commercial you’re given 30 or 60 seconds and most people head into the bathroom when it comes on. But every job was different and interesting and took you around to all sorts of places – I travelled a lot throughout the world – right through Asia and Europe, America and South America, shooting commercials.

Feature films, in a theatre, was always the bee’s knees for any cinematographer. Here you were taken seriously. On the other hand, in the Australian experience, there was more money in advertising. It’s all a matter of scale … here a music video budget was big at $20,000 whereas in America it would $20 million.

What year did you move to Sydney and where did you settle?

Invasion Day 1996, ironically. We rented a property on Pacific Road Palm Beach for a while, which was wonderful, and then ended up buying a property in Whale Beach before prices boomed. It was a rundown place but it was wonderful. I moved to Avalon about 10 years ago.

Were you still surfing then?

Yes – it was only a few years after I got here that I poked my eye out in a surfing accident at the south end of Whale Beach, one of my favourite spots to surf. Because I was living close by I could just check it out from my place and jump on it whenever it was good. Not many people surfed it in those days before surf cams but Martin Potter (Pottz) was often out there, and hardly anyone else usually. It was a brilliant spot until the day I poked my eye out with my fin.

What was it like to lose an eye when you love being behind the camera?

It was painful and I almost passed out because I was concussed too – I was lucky to survive. The beach was closed and there were no life-savers, so I had to rescue myself. Career wise, at first it was pretty bad and felt like going from rooster to feather duster overnight. I had been working with the best directors in town and suddenly the phone stopped ringing. It was a bizarre time.

You could still see though?

Yes – it’s a monocular job, you need only one eye against the lens, that’s the way it works, but there was also always this joke ‘you only have one eye, you can work for half price.’

Underneath that kind of blunt Australian humour was a lot of intent as well. I was seen as damaged goods. So I ended up directing a lot and working overseas a lot. That was part ‘stuff you!’ but I found that just when things were going quiet here I was starting to boom overseas.

Where did you go?

Mostly Asia in countries such as Japan, China, Korea and even India. I also did a lot of work in SE Asia - in Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam and the Philippines. These were all commercials. The style of these SE Asian commercials were very old school, but the scale of their marketing was impressive. I remember one if did for the Indome company to promote an instant noodle product made from wheat (from Canada, not Australia because we hadn’t got into that market). Indome sold 18 million units of that instant noodle product every single month. The scale of it was just mind boggling … and the market there had by and large only just got into TV advertising.

When did you put your first book out?

The first one was when I was in recovery from losing the eye. In 1999 I authored and published a book called ‘Australienation’ - a pun on the word ‘alienation’ - a book of black and white photographs. It was designed by John Witzig, who used to be editor at Tracks. Then I was back in film-making for a while but I’d also gone through a divorce, travelled to Africa, then lived in Prague for a while, moved around a bit, writing, painting and taking photographs.

Most people may not know you also painted...

I only did it for a short time but one of my paintings, of Gretel Pinniger, won the Real Refusé at Tap Gallery. It takes me a long time to paint and for me, a painting is never finished, simply abandoned, or put aside, so I went back to photography again because I find it easier to move on.

A lot of your books sell out, quite difficult to do for a self-publishing press – why do you think yours are so successful?

Well, they’re only small print runs. In America you have 50 thousand and 100 thousand print runs – with the Saltwater books I’ve only done a 3000 print run. When you are publishing $100 local history books, there is only a small market. Big publishers don’t do local history books anymore.

On the northern beaches people appreciate the work that has gone into such a book. There’s not a hell of a lot of profit in it even if you do sell out, I’ve had to borrow money from the bank to make these books so it’s a highly speculative enterprise.

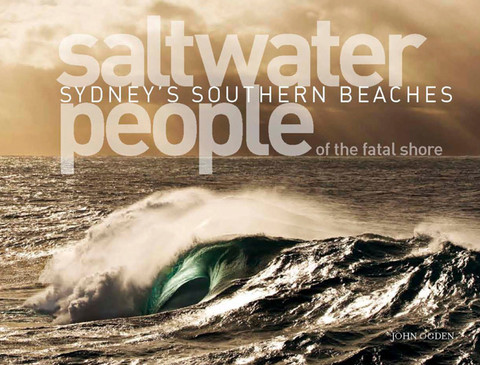

Your second book in this series – Saltwater People of the Fatal Shore – Sydney’s Southern Beaches. This was to compliment the first book – Saltwater People of the Broken Bays – where does it start from?

The geographical boundaries are from South Head to the Royal National Park inclusive. It was difficult to find the right title because when you say southern beaches, people think of the Wollongong area, but it covers the south-side beaches of Sydney.

‘Fatal Shore’ is a reference to Robert Hughes book ‘Fatal Shore’ but he actually took that title from a poem that was written by a transportee to Van Diemans Land who was writing about there but I think it’s really appropriate for that section of coastline. It’s where Captain Cook first sailed into and first trod on the land here and then where the First Fleet arrived – so it was the sharp end of the European Invasion so that’s why the ‘Fatal Shore ‘ – it has other repercussions to it.

How long did it take to put this one together, to track down the correct archival photos to go with the archival text?

Yes, history can’t be made up - it has to be correct. The Northern book was about a year and a half of research in it and while I was doing that I actually put aside a lot of stuff I was turning up on the south-side but I think it was about a year of extra research for the new book – so slightly shorter. It was also basically a companion book so I knew what I was doing from the first one. It follows the same format.

The northern beaches book went so well, it seemed a no-brainer to do a companion book on the south-side. This coastline has more stories than the first book, mainly through people pressure, so the new book is bigger – it has 24 more pages then the North book to try and fit it all in.

A lot of people get upset by the word ‘Invasion’ but there’s no other way to really look at it. There was over one thousand soldiers and convicts who arrived in the First Fleet and there was only an estimated population of 5000 Aborigines living along the coastline. It would be like 500,000 armed foreigners arrived in ships at the same time right now – you’d think of it in terms of invasion. It’s not hard to see why Aboriginal people would get offended by things such as Australia Day, which is celebrated on the date of the arrival of the First Fleet.

I went to a talk by Henry Reynolds the other night on his new book ‘The Forgotten War’ and he makes the point that there are two ways to take a country – one is by stealth, by stealing, by force, and the other one is by treaty. We never had a treaty with the Aborigines so the consequence of that is they were invaded…and he has done a lot of research that shows there was a war that has been forgotten.

Apart from those sensitivities, Aboriginal nations along this coastline should be viewed as maritime nations, with a canoe culture. A lot of their exploration of the country was done via the coastline, as Europeans had done in more recent times. A lot of my help from the books came from Keith Vincent-Smith a well known historian who wrote a book called 'Mari-Nawi' which means ‘Big Canoe’. He did a lot of research on canoe culture that was developed into an exhibition at the State Library of NSW (2010- MAKING OF THE CANOE A full-scale model of a Sydney bark canoe is the centrepiece in the Library's new landmark exhibition Mari Nawi: Aboriginal Odysseys 1790-1850.) That was the genesis of what was to become an annual event or a convention of indigenous canoe making – this has been fantastic as people come from different parts of Australia and demonstrating the different ways that canoes were constructed. The canoes are quite impressive in their design and practicality. See: http://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/podcasts/videos/mari_nawi.html

Early European ships would see people fishing in these canoes up to two kilometres out at sea, out in big surf, so they were actually quite well-made craft even if they didn’t look like it. The convention has become a quite popular event and is a point of pride with Aboriginal communities.

People who have bought the first book – what would they get from this second book?

It will give them a broader view – one of the interesting things about the South book is that it includes Botany Bay area and the remarkable history of that area. One of the things about Botany Bay is that it was once a garden of Eden … people only had to work a few hours a day to have enough seafood and what else to live and the rest of the day was devoted to ceremony and family. Within a short period of time after European settlement, it was turned into pretty much a toxic dump. Many toxic industries, such as wool-washing, the oil refineries, the early powerhouse, were put in that area … followed by dredging and land filling to build the ports and the third runway, creating erosion issues. Fish breeding grounds were destroyed and the famous Botany Bay oyster now extinct. This area represents an analogy to what could happen to the rest of the coastline. Fortunately, there has been a lot of work recent years to remediate those problems. By looking at the culture of the First People a very strong sustainability thread runs through the books – especially in relation to water cleanliness and land use.

The other thing is that Botany Bay was the arrival place for the first Europeans on the east coast. In the lead up to the last elections there was a lot of political and media fear mongering about refugees arriving by boat. It is a point of irony that this is exactly how the first settlers arrived just a few centuries earlier. The other aspect is of course that the larger amount if illegal immigrants arrive by plane – so they’re still arriving at the Botany Bay area, now via the country’s main airport – so that’s another little irony as well.

You have just published a new book ‘Slightly Dangerous’, what is this about?

I started writing down stories when I began to go blind in my other eye (from a cataract) around 2008, and couldn’t work in film for a while. Fortunately the corrective surgery was successful. Then, at the beginning of this year (2013), I had an exhibition at the Manly Art Gallery and thought I’d finish off my note to clarify different points of this exhibition. I was getting good feedback and ended up creating a book. The exhibition ended up being a retrospective as I spent so much time working on the book that I didn’t take many new pictures. I had just turned 60 so it was a good time to look back and reflect. ‘Slightly Dangerous’ is a collection of stories, not an autobiography, and more about influences and inspirations … just as we have been talking about today.

How many photographs to do you estimate you have taken throughout your career?

I looked at 300 thousand images when I was doing research for the Portraits book so it’s more then that. I guess it would be over half a million.

You have created your own path in many mediums, gone out and done it for yourself. What would you say to anyone who is beginning to work in photography, film, painting, and publishing books about how to achieve what you set out to do?

The main thing would be that it’s tough, unless you’re incredibly lucky. That’s what that book was about … looking back at a quite extraordinary time. It’s always incredibly difficult to look forward and see the path ahead - and much easier to look back and join the dots. By doing that process you can see that just by following your heart it creates; a kind of ‘if you build it they will come’ manifestation. That’s always been my philosophy.

The world is changing - it’s very different to what it was when I started off – there were hardly any film schools, and not many photo journalists, and now we’re swamped with new media. Everyone has a camera, every phone has a camera. If you want to stand out in a party crowd now you say you’re an accountant rather than a photographer. It may be easier to get access to information, but maintaining a career can be tough. There are a lot of graduates coming into a shrinking market. Newspapers are sacking their staff, and journalism has become more an advertising job than exposing the truth.

All the industries I’ve worked in - photography, film, publishing – they have all been quite dramatically impacted by the digital revolution accompanying the information age. There’s good and bad things about that. When I started in the film industry it was a 5-6 year apprenticeship before you got near a camera, because cameras cost millions of dollars back then and it was a thousand dollars for every three minutes of film (35mm film). Now the digital evolution has democratised the process by making it more affordable. This means you can get an early entry … but the problem then becomes longevity, because there’s always someone who is going to come up and do your job for free.

To have a career in these fields, and raise a family, and all the costs of living in a place like Sydney, it’s going to be a really tough career choice. There’s probably safer careers to do. Technology has reached its expediential curve where the things invented in the 20th century are more than the two thousand years before that and what has been invented in the last ten years is more than the last century. That expediential curve means it’s pretty hard to predict what’s coming up … which can be exciting … but it can also create a lot of anxiety.

What’s coming up in the future for you?

Cyclops Press is about to launch a book by author Peter McConchy titled Fire and the Story of Burning Country. In a similar vein to 'The Biggest Estate on Earth' by Bill Gammage, Fire challenges long held perceptions and helps us understand traditional land care and management – this time from the Aboriginal perspective. In these pages the Elders explain to us “we need fire because Australia is a fire nation”. Fairly timely as we approach a hot summer and having watched Barrenjoey burn.

Personally, I’m currently working on a book and a film script that I can’t talk about now, but hopefully you will read about here in the near future.

What is your favourite place/s in Pittwater and why?

Barrenjoey – when I stand up there it probably has the best view in Sydney – it’s almost a 360 degree panorama.

What is your motto for life or a favourite phrase you try to live by?

There is a recent one – The eyes are useless when the mind is blind.