Address given Tuesday 4 November 2025 in the Australian Parliament on the Environment Protection Reform Bill 2025

Item: BILLS - Environment Protection Reform Bill 2025, National Environmental Protection Agency Bill 2025, Environment Information Australia Bill 2025, Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (Customs Charges Imposition) Bill 2025, Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (Excise Charges Imposition) Bill 2025, Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (General Charges Imposition) Bill 2025, Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (Restoration Charge Imposition) Bill 2025 - Second Reading

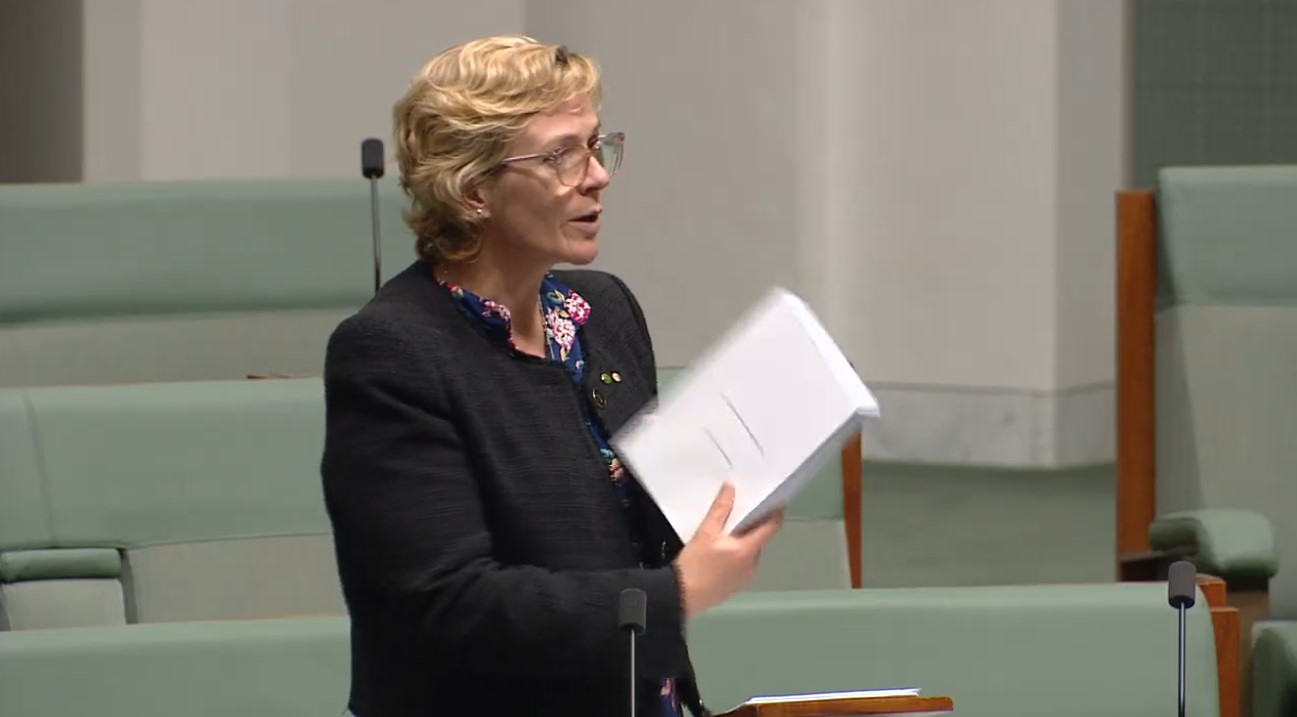

Dr SCAMPS (Mackellar) (Time - 18:59, November 4 2025):

I rise to speak on the Environment Protection Reform Bill 2025. There is broad agreement that the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act, or EPBC Act, has utterly failed to protect our environment for the past 25 years. We now have 19 ecosystems on the brink of collapse, and we are a global deforestation hotspot, along with Bolivia and Brazil. I want to begin by saying, sadly, that I cannot support the environmental reforms in these bills in their current form, because, quite simply, they do not guarantee protection for our nature.

The EPBC Act is the one piece of national legislation that we have to protect our environment. It should be our nation's safeguard for the environment—the framework that ensures that our forests, rivers, oceans and wildlife are not irretrievably polluted and destroyed but protected for future generations. This package of reforms was intended to fix our national environment laws, but instead it risks entrenching the very weaknesses of the current EPBC Act that have allowed Australia's environment to decline so sharply.

It is well understood that business needs greater certainty when it comes to project approvals. For Australia to meet our climate goals and unlock the enormous potential of renewable energy, we need clear, consistent and trusted environment laws. But right now many projects, including renewable energy projects, are being delayed or bogged down in confusion. Communities, investors and industry are all calling for the same thing: an approval process that is efficient, transparent and fair. Businesses need clarity on how decisions are made and they need to know that if they put forward a strong, environmentally sound proposal they'll get a fast 'yes' and if a project isn't up to scratch they'll get a fast 'no', so they can move on and refine their plans—not waste money—and invest with confidence elsewhere. That's what a well-functioning system delivers: speed, certainty and integrity.

But this cannot come at the expense of nature. A healthy environment underpins a healthy economy. The two work hand in hand. So it is critical that this time around our nature protection laws do actually protect nature and that we don't see another 25 years of environmental neglect. Once ecosystems are destroyed, once species are extinct, no amount of economic activity or offsetting can bring them back.

The people of Mackellar understand deeply the need to protect nature. They want their children and grandchildren to have the same connection to the coast, the creeks and the wild beauty that we've been lucky enough to grow up with. That's why they've asked me, as their representative, time and time again, to push for strong reforms to our national environment laws and to stop the destruction of our unique ecosystems, plants and animals that has occurred relentlessly in this country over the past few decades. They want a system that protects our environment and provides predictable, efficient decision-making for business. This is entirely possible, but these reforms are not it.

I have a number of concerns about these reforms that I'll go through in detail. Let me turn to the first major concern: the new national interest exemption. Under this provision, the environment minister could approve a project even if it includes what are deemed to be unacceptable impacts to the environment, so long as the minister deems that it is in the national interest. That's an enormous power. It effectively lets the minister override the law and to do so without having to explain why. While the minister must generally publish a copy of the decision, together with the reasons, this accountability mechanism can itself be avoided when the minister believes it is in Australia's national interest to not provide these details.

Ken Henry has warned that the national interest test in these reforms is likely to incentivise significant lobbying from developers, as they are all absolutely convinced that their project is in the national interest. The legislation cites projects relating to defence, security and national emergencies as the types of projects that might attract the exemption, and the environment minister has confirmed it could be used for something like a rare earth mine or a gas project if that was what the minister of the day decided. But at the end of the day the minister only needs to be satisfied that the action is in Australia's national interest.

It doesn't take much imagination to think about how this could be exploited. In fact, earlier this year, then opposition leader Peter Dutton said he would use the existing national interest test to fast-track the North West Shelf gas extension—a project that the Australia Institute estimates would release around 90 million tonnes of emissions every year, equivalent to building 12 new coal-fired power stations. This isn't about whether you trust the current minister; it's about what a future government, perhaps one less committed to protecting our environment, could do with such sweeping discretion.

That brings me to the next serious flaw—the bills' overreliance on ministerial discretion throughout. The Samuel review found that the existing EPBC Act insufficiently constrains decision-maker discretion, leading to uncertainty and poor environmental outcomes. Yet these reforms expand and entrench ministerial discretion rather than curtail it. Key decisions and tests throughout the bills depend on whether the minister is 'satisfied' that something is the case or whether an action is 'not inconsistent with' national environment standards. That kind of subjective language weakens the law.

The new environmental standards, which are meant to be the centrepiece of this reform, are riddled with this type of language and subjectivity. For example, an approval must not be inconsistent with a standard but only if the minister is satisfied that's the case. The no-regression principle, which is meant to ensure standards don't go backwards, applies only to the satisfaction of the minister. The provision requiring approvals to pass the net-gain test, which is an important guardrail on the offset provisions, is subject to the satisfaction of the minister. There is also a high level of discretion available to the minister in providing for declarations or bilateral agreements to devolve powers to the states and territories, along with many other crucial checks and safeguards. Indeed, earlier this year, when there was a threat that the EPBC Act might actually be used to protect a species—the Maugean skate—the government stepped in and amended the bills. This is not the strong objective framework the Samuel review recommended.

Next is the carve-outs and blanket exemptions. For decades, exemptions in the EPBC Act have allowed destructive activities to continue without federal assessment or approval, even when they impact threatened species or critical habitats. The most glaring examples are the regional forestry agreements, which exempt native forest logging from EPBC Act oversight and the continuous-use, or prior-authorisation, exemptions relied upon by proponents of agricultural land-clearing.

Since the EPBC Act was introduced more than two decades ago, our environment has only declined further. Australia is now the only developed nation on the list of global deforestation hotspots. Our forests are being bulldozed at pace, pushing species like the koala, the greater glider and the grey-headed flying fox to the brink of extinction. While the government has said that the national standards will apply to forestry activities it's difficult to see how this will work in practice, given the proposed standards do not yet exist and given forestry activities are exempt from the act.

I simply do not accept that native forest logging should be exempt from our national environment laws on the basis that state laws can be relied upon instead. You need look no further than my home state of New South Wales to see why. In New South Wales, environmental requirements have been repeatedly breached by the Forestry Corporation of NSW. In a judgement in the New South Wales Land and Environment Court last year, Justice Rachel Pepper noted the Forestry Corporation's lengthy record of prior convictions for environmental offences, including polluting a forest waterway, inadequate threatened species surveys, unlawful harvesting of hollow-bearing trees and harvesting in koala and rainforest habitat exclusion zones. That's why I'll be moving amendments to these bills—to repeal the exemption for the regional forestry agreements and the continuous-use exemption.

Another concern is the devolution of federal powers to state and territory governments, particularly in relation to the water trigger. The bill empowers the minister to accredit state processes and enter into bilateral agreements so that states can assess and approve projects on behalf of the Commonwealth. While this could improve efficiency, it comes with an enormous risk. Of particular concern, the water trigger will be available for devolution despite being specifically excluded from bilateral approval agreements and regional plans in the current laws.

Next, I'm deeply concerned regarding the approach to offsetting. There is no requirement for developers to avoid or reduce damage before moving to offsets under the mitigation hierarchy, only that the minister must consider the hierarchy. This will likely entrench offsetting as the default option rather than the last resort. The net gain test is designed to ensure that actions cannot be approved unless impacts on protected matters are offset through actions that result in a net gain. However, concerningly, this can be satisfied through the payment of a restoration contribution charge to the restoration contributions holder. This allows for habitat-destroying developments to be deemed to have a net gain on a protected matter despite the impact being irreversible. The proponent can simply pay into the fund and thereby bypass the true net gain test, and there are no provisions requiring adequate accounting for delivery of the net gain.

The reform package also establishes a national environmental protection authority, NEPA, which is welcome in principle. But there is a glaring flaw. The government has chosen not to create a governing board, and there is no independent appointment process for the CEO. This is exactly the kind of political appointment risk I tried to address through my own 'ending jobs for mates' private member's bill, to ensure independent and transparent selection processes for key public roles. Without those safeguards, NEPA risks being just another arm of government rather than a truly independent watchdog.

We've seen state based environmental regulators marred with this type of controversy. In New South Wales, the EPA was recently accused of bearing a report on lead contamination in children's blood to placate mining companies. In the Northern Territory, the EPA chair was involved in decisions on a major gas leak scandal without disclosing his paid role with an industry lobbying firm. In Western Australia, the EPA was forced to withdraw its 2019 emissions offset guidelines after intense pressure from the gas industry and the state government. When regulators appear to be bending to political or industry pressure, whether that bending is real or perceived, public confidence evaporates. If we want to rebuild trust, this regulator must be genuinely independent, properly resourced and protected from political meddling.

Finally, we cannot talk about environmental protection in 2025 without talking about climate change. Yet these reforms studiously avoid it. Unsurprisingly, the government has again refused to include a climate trigger, a mechanism that would require assessment of a project's greenhouse gas emissions as part of environmental approvals. The International Court of Justice's recent advisory opinion confirmed that countries like Australia are bound by international law to assess and limit greenhouse gas emissions, including those from exported coal and gas. While the government argues that the safeguard mechanism already regulates emissions, this only applies after a project is operating. It doesn't stop new, high-polluting projects from being approved in the first place. In the last term alone, the government approved 27 new coal, oil and gas projects, with four new approvals this term. Their combined lifetime emissions are expected to exceed 6.5 billion tonnes of CO2.

A reformed EPBC Act that ignores climate is a reform that fails to meet the moment. This reform is an opportunity, a once-in-a-generation chance to fix our broken system, restore trust and put nature at the heart of decision-making, while providing a more efficient process for business and investment. As it stands, the bill does not do that. It risks repeating the very mistakes that the Samuel review warned us about—too much discretion, too little accountability and too many loopholes. I urge the government to work with the crossbench, to listen to the experts and to strengthen this legislation so it genuinely delivers for our environment, our economy and future generations.

![]()