January 6 - 12, 2013: Issue 92

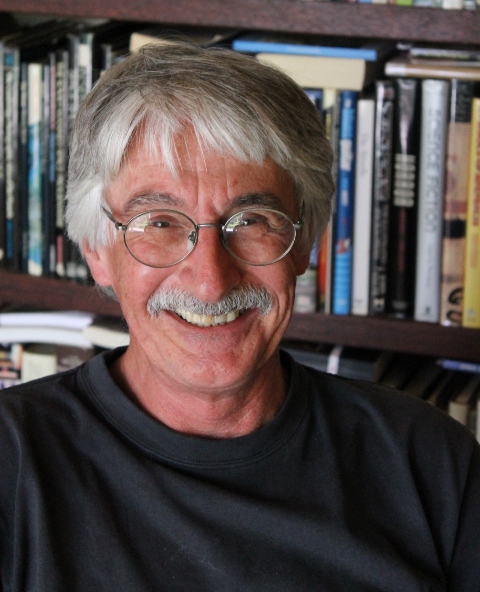

Edwin Barnard

Editor,

author, and historian Edwin Barnard has a passion for tracking down and

reinstating within clear view our Australian heritage, history and culture.

Editor,

author, and historian Edwin Barnard has a passion for tracking down and

reinstating within clear view our Australian heritage, history and culture.

We’re in your office today Edwin and there’s quite a few books here. Where did this attraction for books originate from?

My parents had a lot of books. I think you grow up with a love of books if around them all the time. I always knew I’d be involved in books from my childhood.

There’s some lovely old Australian books here, particularly on Antarctica and straight underneath these are works on Mount Everest, what has caused you to collect those?

Antarctica because I did a book on Antarctica years ago, so I collected a lot of material then, Mount Everest because I was interested in mountaineering for while and did a bit of climbing. I never got to the Himalayas.

Where did you climb?

In New Zealand. I read a book by a famous English mountaineer and thought 'gosh that sounds like good fun'. I did it until I fell off a mountain; I did it partly because my son was sixteen and we could to this together. We did a mountaineering course in New Zealand and then we went back and climbed Aspiring … it was good fun climbing with him when he was in his teens plus there was.. ‘This looks hard and dangerous Peter, I think you should join me.’

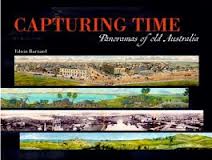

You have written a fair amount of books and this latest one, Capturing Time – Panoramas of old Australia, a beautiful book, presents images and information on Australia that would normally be hidden away in archived boxes. How did this new work begin?

I’d originally planned to do a book on convicts as that seems to be a book that nobody has done a proper book on. I put some specimen pages together and among that material was some photographs that I found at the National Library of convicts taken in 1876, a lot of whom were transportees who were pretty old men by then, and it struck me that somebody must have done a book on this collection of photographs but there didn’t seem to be a book of photographs of transportees in existence anywhere.

I tried to interest various people in a book on convicts and couldn’t. So I then decided that maybe I’d make a book out of the photographs and did some specimen pages for those and took it to the National Library and they liked the idea. You may have seen this book, Exiled: the Port Arthur convict photographs. In the process of doing that I came across some panoramas and thought well, here’s another good subject for a book. The National Library liked that and they then bought that idea.

How many books have you published altogether?

An awful lot. They’re all major projects so they all take two or three years to do and I’ve done twenty, twenty-five now.

Are they all filled with Australian content?

No. I worked in London for Reader’s Digest books

for a few years and worked for them when I came out to Australia. I then went

freelance and did some work on a book on Antarctica in-house and they decided

they were dropping a book so I decided to take it outside and do it myself

having already spent an immense amount of money putting it together and

gathering material.

I’d spent years on that book already, gathering pictures

from all over the world, even now a lot of the photographs I’ve never seen used

before. I also came across the most extraordinary archives of notes and

photographs that have ever been published, some of which have still never been

published. It was stunning; there’s so much material out there that nobody uses.

Nobody has got the get up and go to actually find this material, they just use

the same stuff.

As soon as the book came out I had people ringing me up saying ‘that photograph on page 67, where did you get that from?; because I want to use it’. I’m inclined to say ‘bugger you, go out and find your own pieces, there’s so much new material out there for you to find that nobody has used before.’

When you get involved in a subject is there a passion that comes that leads you to explore all involved that then leads you to more material, to finding content not known prior to then?

Yes, that happens as part of the process. By the time I finished Panoramas I could have produced ten more books. That’s what happened with Antarctica; it took on a life of its own. It was years ago that I did that book and I still collect Antarctica material when it turns up but of course it never turns up these days because the Japanese have bought it all up.

Of all the works you’ve done which would be your favourite?

The one I’m working on at the moment.

So you’re working on something new?

Yes, also for the National Library and that emerged again out of that book (Capturing Time – Panoramas of old Australia). An idea occurred to me as I was doing that ‘this would make a good book that nobody has done before’.

It must be very satisfying to bring together all this material and make an accessible record of it?

Its great fun. I’ve not enjoyed myself in all my life as much as I do now; because I’ve got so much freedom now. I don’t work well with an organisation so I haven’t worked in an organisation since 1980. I hate organisations, they’re so self-defeating. You spend your whole life fighting office politics and people’s egos and I’m much more productive sitting here. I can do what I like and have total control over the projects; I do all the design, all the research and all the writing so the book is what I want to be exactly. It’s good fun and I’ve got the time to do it properly.

Let’s go back to the beginning; where were you born?

Born in England in 1944, in Old Basing, Hampshire.

Did you grow up there?

Until 1949. my parents emigrated after the war (WWII); there didn’t seem to be much point in Britain at the time; it was a pretty grim place from all accounts so they … the toss up was South Africa or here and I’m glad they chose here.

Whereabouts in Australia did they land?

They landed in Melbourne and then we went to live with somebody my mother knew on a soldier’s settlement at the back of the Snowy Mountains, this was 1949. It was quite an amazing place. A bit different from England.

Where were you educated?

Half and half…here and back in Britain. My parents went back twice and so my education chopped and changed between here and Britain. I finished High School here in Sydney.

Did you go on to University then?

Not then. I went to University about ten years ago for the first time.

Bit of an eye-opener?

It was marvellous, it was just a wonderful experience.

Do you think you learnt more as an adult student then you would have going straight out of High school?

Oh yes. I’m so glad I didn’t go straight out of High School. It was the value of the one to one contact with somebody, to have the conversations that you can’t have elsewhere; you start a conversation about Philosophy around a BBQ everyone gasps (draws back) whereas in University it’s different…where else can you have these conversations other then with someone whose whole life revolves around this subject. And that was the fun…meeting and talking to people about those sorts of issues, a conversation you’d never have anywhere else.

What did you do when you left High school?

Got a job. I think I worked as a plumber’s labourer originally.

How did the shift to the publishing world come about?

It was curious…that came about mainly because my father, he was a sort of polymath and did dozens of jobs during his life. One of them was books; he took it into his head that he wanted to publish some books, so we did some books at home which he sold to A. H. and A. W. Reed, and they sold well.

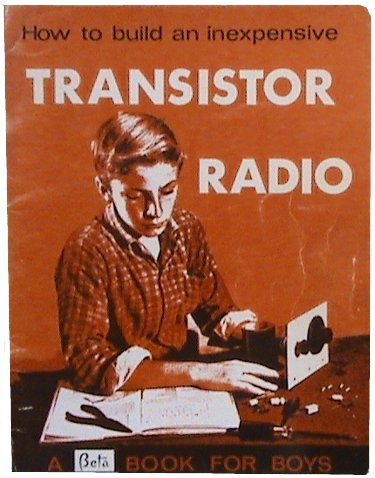

What

were the subjects?

What

were the subjects?

One was Making an Astronomical Telescope because he was interested in making telescopes and one was on making a simple transistor radio (1965) and so we did all this at home. It was that pedigree I used when I went to London and applied for a job in publishing there. It jus happened to click with what they wanted at the time, someone who had done that kind of book. It was a lucky break for me because it got me into publishing to begin with. That was with Reader’s Digest books.

How long were you with Reader’s Digest?

I was there for about four years and when I came here I was with them for about ten years as a Project Leader. Those were the great days of book publishing. Originally in London, it was an extraordinary time because we just couldn’t do anything wrong. They were willing to spend big money on books; we’d spend a million pounds on a book. It paid off hugely. The first book they put out was A Motoring Guide to Britain. They did their Market Research, which was the whole strength of that outfit, and the Market Research said well, you ought to print 1.25 million copies at £35 each. They said, that can’t possibly be right, that’s far too many. So they printed 750 000 and then had to write to half a million people saying why they couldn’t have their books. The Market research was right, they had to put out more books; we just sold so many of them.

There wouldn’t be too many households here or in Britain that wouldn’t have at least one Reader’s Digest volume.

That’s right, most do.

So you left Reader’s Digest ?

And went out on my own and began packaging projects.

A good position to be in?

It was and it lasted for a number of years until they went broke and so work dried up. I then found other publishers, other projects to do.

You have been back and forth to Britain and Australia, which place feels like home?

I think a critical phase in your life, from around five to ten, is when you’re forming friendships and you’re getting out in the world and seeing the world independently, and for me that happened in Australia and it happened at the time we were living down in Albury. So I grew up as a kid in a country town at a time when you could wander off to the hills with your mates and a billy cart. I’ve still got very fond memories of that Australia, because it was a very different Australia to this one.

Did you notice any post-war characteristics in Albury?

Yes! There was an Army Camp there of course and they had a depot of or storage of equipment that just went on for miles and miles. It was junked equipment. Tanks; talk about a wonderful play area. Just mile after mile of it, I suppose it’s all disappeared now, sold for scrap presumably but it’s extraordinary how much stuff was stored out there.

In your experience what are the main shifts that have occurred since the 1950’s?

I think it has lost its unique character, what made it Australia. I think it’s become an international place…it’s been changed to become more international and now the trouble is Sydney…Paris, Rome Berlin…they’re all the same. You go to all the same shops selling all the same things and Australia wasn’t like that.

I admit it had its drawbacks in those days, it was a very insular place, but it had its own unique character. In researching another book I did, a guide to Australian places, I chose as an area to do the area around Taree, just visiting all the little towns and looking at their history, and it was extraordinary, the end of the 19th century how innovative these places, country centres like Taree were. They had their own shipping industry, ship-building; they had all their own local industries, were tidy, self-reliant. They produced all their own goods and products and food. And all that’s gone. I think that really has changed and, to a certain extent in the ‘50’s I could still just see that in places like Albury but that’s all been swept away.

It’s hard to define exactly what it was about Australia in the 1950’s that was so different. You still meet that when you got out into the country. One example I like to quote to try and define what I mean;

When I left school a friend and I decided to hitchhike around NSW in the summer holidays. We were in central NSW, and it was bloody hot, in a place just out of Condobolin; it was marked on the map as a settlement and we got there and it was just a country store, nothing else there. It was a boiling hot day, the gum trees were wilting, their shade was hot, and we went into the country store to buy something to drink, and the guy said ‘where are you fellas from’ and we told him and we were planning to continue walking down the road, if we could pick up a lift, to get to the next town. And he said, ‘oh right, well see ya.’ And an hour down the road a car drives up from the other direction and does a u-turn and a bloke says ‘Hop in’ and says ‘the guy in the store rang us’, and they’re ten miles down the road, ‘we’re going into town tonight and we thought we’d give you a lift into town.’

It was amazing. They took us back to their house, they were going in to a dance that night and they took us to that. And I thought ‘gee, what generosity’, it was extraordinary.

And then, it was about five years ago, I was

driving through Glebe, down Glebe Point road, and a guy runs out of a house and

looks round frantically and waves me down. He said ‘I missed the bus. Can you

possibly give me a lift to central Station?’.

I don’t know what it was, there

was something about the way he did it. I drove him down to Central Station and

asked him ‘where are you from?’. He answered ‘I’m from a property out at …’ and

it was exactly what somebody from the country would do..just, you know, here’s a

bloke, he’ll give me a lift.

Is that part of the attraction of finding and publishing unique Australian characteristics or histories?

Yes, I like 19th century Australia. It was an interesting place.

When did you move to this area?

A long time ago, fourty years ago.

You’re living in one of the original streets, there’s original cottages here…

Yes; the people over there, when they bought here, the deal was ‘buy one block of land get one free’.

What has kept you here?

It’s a nice place to live. It’s just right for me, the right distance from the city, you can get to the city in fourty minutes. I must say that though I like the country, I like the city. I like what is here; I like bookshops, coffee shops, libraries. There’s something about the city I quite like as well but I don’t want to live in the city, I like living here. It’s close to the beach and it’s quiet.

You like the environment?

Yes, I go bushwalking. I’ve done a lot of walking, all over Australia, in South America, the middle East…all over the place.

What’s your favourite walk that you’ve been on in Australia?

Probably The Flinder’s, or the Gammon Ranges, wonderful place.

Capturing Time – Panoramas of old Australia promo material states these works were the IMAX of their age, that they were big; have you seen any of these originals?

The original idea behind panoramas was to send somebody off to some exotic place and he came back with a series of sketches, maybe ten sketches, and these were then transferred to the wall of the panorama room. The originals often aren’t that big. Some are; the one that was done of Melbourne in 1841, which is huge. That’s about, from memory, about nine metres long. Unfortunately that’s not available. There’s some very poor images of that available on the web. I rang the State Library of Victoria and asked if I could come down and look at it and take some photographs and found it was nailed up in a crate in storage in Bendigo and was told they can’t get it out.

The word "panorama", from Greek pan ("all") horama ("view")

was coined by the Irish painter Robert Barker in 1792 to describe his paintings

of Edinburgh, Scotland shown on a cylindrical surface, which he soon was

exhibiting in London, as "The Panorama".

In 1793 Barker moved his panoramas

to the first purpose-built panorama building in the world, in Leicester Square,

and made a fortune. Viewers flocked to pay a stiff 3 shillings to stand on a

central platform under a skylight, which offered an even lighting, and get an

experience that was "panoramic" (an adjective that didn't appear in print until

1813). The extended meaning of a "comprehensive survey" of a subject followed

sooner, in 1801. Visitors to Barker's Panorama of London, painted as if viewed

from the roof of Albion Mills on the South Bank, could purchase a series of six

prints that modestly recalled the experience; end-to-end the prints stretched

3.25 metres. In contrast, the actual panorama spanned 250 square metres. In the

mid-19th century, panoramic paintings and models became a very popular way to

represent landscapes and historical events.

Panoramic painting. (2013,

January 2). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Panoramic_painting&oldid=531001577

If you could be another creature for a day, furred, feathered or finned, what would you be?

I’d kind of like to be a wombat. I like wombats, they have an interesting character.

What is your favourite place in Pittwater and why?

Bangalley headland and Barrenjoey; places that have a view and a story as well. The coastline from Bangalley around to Whale Beach is spectacular.

What is your ‘motto for life’ or a favourite phrase you try to live by?

At my mother’s funeral I chose Donne’s piece ‘No man is an Island’. I think that’s a wonderful piece of writing. I think that sums up our predicament pretty well and would choose that.

'No

Man is an Island'

No man is an

island entire of itself; every man

is a piece of the continent, a part of

the main;

if a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe

is the less, as

well as if a promontory were, as

well as any manner of thy friends or of

thine

own were; any man's death diminishes me,

because I am involved in

mankind.

And therefore never send to know for whom

the bell tolls; it

tolls for thee.

Olde English

Version

No man is an Iland, intire of itselfe; every man

is a peece of the

Continent, a part of the maine;

if a Clod bee washed away by the Sea,

Europe

is the lesse, as well as if a Promontorie were, as

well as if a

Manor of thy friends or of thine

owne were; any mans death diminishes

me,

because I am involved in Mankinde;

And therefore never send to know

for whom

the bell tolls; It tolls for thee.

MEDITATION XVII

Devotions upon Emergent

Occasions

John Donne

Capturing Time - Panoramas of old Australia

Pittwater

resident Edwin Barnard has recently released the most beautiful book for art

lovers as much as those who love Australian History. Panoramas, whether painted or photographed, were the nineteenth-century

equivalent of IMAX or Google maps. These wide-angled views of landscapes and

cities fascinated viewers, who had never before seen such far-reaching

perspectives on the world around them.

Pittwater

resident Edwin Barnard has recently released the most beautiful book for art

lovers as much as those who love Australian History. Panoramas, whether painted or photographed, were the nineteenth-century

equivalent of IMAX or Google maps. These wide-angled views of landscapes and

cities fascinated viewers, who had never before seen such far-reaching

perspectives on the world around them.

Based on the National Library of Australia’s extensive collections, Capturing Time: Panoramas of Old Australia looks back on our nation through the magic of panoramas—to the streets of Sydney when it was the convict capital, to the gold rushes of Melbourne and to Perth, struggling to establish a toehold on the continent’s western frontier.

Dating from 1810 to the 1920s, the paintings and photographs include historic views of all of Australia’s capital cities, plus some country towns. Not only can readers imagine what it might have been like to stand on Sydney’s Observatory Hill in 1820, for example, but also what it would have been like to stand there with a companion able to point out landmarks and tell the sorts of interesting stories that only locals know. Purchase from here

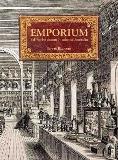

Emporium: Selling the Dream in Colonial Australia by Edwin Barnard- Editor, Author, Historian and Avalon gentleman, Edwin Barnard's new book Emporium uses collections of advertisements as starting points in assembling a series of self-contained ‘snapshots’ to paint a lively and entertaining picture of everyday life in the Australian colonies.

Emporium: Selling the Dream in Colonial Australia by Edwin Barnard- Editor, Author, Historian and Avalon gentleman, Edwin Barnard's new book Emporium uses collections of advertisements as starting points in assembling a series of self-contained ‘snapshots’ to paint a lively and entertaining picture of everyday life in the Australian colonies.

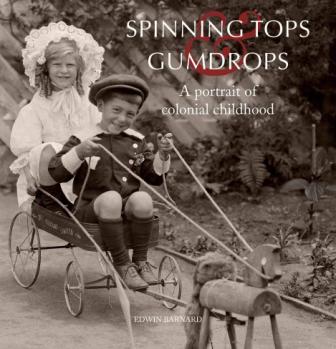

Avalon Beach Authors' Forthcoming Release - Spinning Tops & Gumdrops: A Portrait Of Colonial Childhood