January 20 - 26, 2019: Issue 390

Illuminating Women's Role In The Creation Of Medieval Manuscripts

January 2019: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History

During the European Middle Ages, literacy and written texts were largely the province of religious institutions. Richly illustrated manuscripts were created in monasteries for use by members of religious institutions and by the nobility. Some of these illuminated manuscripts were embellished with luxurious paints and pigments, including gold leaf and ultramarine, a rare and expensive blue pigment made from lapis lazuli stone.

This is dental calculus on the lower jaw a medieval woman entrapped lapis lazuli pigment. Credit: Christina Warinner

In a study published in Science Advances, an international team of researchers led by the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History and the University of York shed light on the role of women in the creation of such manuscripts with a surprising discovery -- the identification of lapis lazuli pigment embedded in the calcified dental plaque of a middle-aged woman buried at a small women's monastery in Germany around 1100 AD. Their analysis suggests that the woman was likely a painter of richly illuminated religious texts.

A quiet monastery in central Germany

As part of a study analysing dental calculus -- tooth tartar or dental plaque that fossilises on the teeth during life -- researchers examined the remains of individuals who were buried in a medieval cemetery associated with a women's monastery at the site of Dalheim in Germany. Few records remain of the monastery and its exact founding date is not known, although a women's community may have formed there as early as the 10th century AD. The earliest known written records from the monastery date to 1244 AD. The monastery is believed to have housed approximately 14 religious women from its founding until its destruction by fire following a series of 14th century battles.

Foundations of the church, which served as a monastery church for the small religious community of women in Dalheim, Germany in the 12th century. © Christina Warinner

One woman in the cemetery was found to have numerous flecks of blue pigment embedded within her dental calculus. She was 45-60 years old when she died around 1000-1200 AD. She had no particular skeletal pathologies, nor evidence of trauma or infection. The only remarkable aspect to her remains was the blue particles found in her teeth. "It came as a complete surprise -- as the calculus dissolved, it released hundreds of tiny blue particles," recalls co-first author Anita Radini of the University of York. Careful analysis using a number of different spectrographic methods -- including energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) and micro-Raman spectroscopy -- revealed the blue pigment to be made from lapis lazuli.

A pigment as rare and expensive as gold

"We examined many scenarios for how this mineral could have become embedded in the calculus on this woman's teeth," explains Radini. "Based on the distribution of the pigment in her mouth, we concluded that the most likely scenario was that she was herself painting with the pigment and licking the end of the brush while painting," states co-first author Monica Tromp of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

The use of ultramarine pigment made from lapis lazuli was reserved, along with gold and silver, for the most luxurious manuscripts. "Only scribes and painters of exceptional skill would have been entrusted with its use," says Alison Beach of Ohio State University, a historian on the project.

The unexpected discovery of such a valuable pigment so early and in the mouth of an 11th century woman in rural Germany is unprecedented. While Germany is known to have been an active centre of book production during this period, identifying the contributions of women has been particularly difficult. As a sign of humility, many medieval scribes and painters did not sign their work, a practice that especially applied to women. The low visibility of women's labour in manuscript production has led many modern scholars to assume that women played little part in it.

The findings of this study not only challenge long-held beliefs in the field, they also uncover an individual life history. The woman's remains were originally a relatively unremarkable find from a relatively unremarkable place, or so it seemed. But by using these techniques, the researchers were able to uncover a truly remarkable life history.

"She was plugged into a vast global commercial network stretching from the mines of Afghanistan to her community in medieval Germany through the trading metropolises of Islamic Egypt and Byzantine Constantinople. The growing economy of 11th century Europe fired demand for the precious and exquisite pigment that travelled thousands of miles via merchant caravan and ships to serve this woman artist's creative ambition," explains historian and co-author Michael McCormick of Harvard University.

"Here we have direct evidence of a woman, not just painting, but painting with a very rare and expensive pigment, and at a very out-of-the way place," explains Christina Warinner of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, senior author on the paper.

"This woman's story could have remained hidden forever without the use of these techniques. It makes me wonder how many other artists we might find in medieval cemeteries -- if we only look."

A. Radini, M. Tromp, A. Beach, E. Tong, C. Speller, M. McCormick, J. V. Dudgeon, M. J. Collins, F. Rühli, R. Kröger, C. Warinner. Medieval women’s early involvement in manuscript production suggested by lapis lazuli identification in dental calculus. Science Advances, 2019; 5 (1): eaau7126 DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aau7126

Get Thee To The Nunnery: Where A Woman Could Get An Education And Degree When All Universities Were Closed To Her

Many modern day scholars state women went into monasteries to receive a higher education when none or very little was available outside of these institutions. Universities

Eudie Pak, in When Women Became Nuns to Get a Good Education, {September 4th, 2018 (Foxtel's History Channel Stories)], states;

Affluent women were required to have some literacy during the Middle Ages, but their learning was intended only to prepare them for being respectable wives and mothers. Higher learning for nuns, on the other hand, was encouraged because they were required to comprehend biblical teachings. So it was no coincidence that many of the earliest female intellectuals were nuns.

Some convent offerings included reading and writing in Latin, arithmetic, grammar, music, morals, rhetoric, geometry and astronomy, according to a 1980 article by Shirley Kersey in (Vol. 58, No. 4). Spinning, weaving and embroidery were also a large part of a nun’s education and labor, writes Kersey, particularly among nuns who came from affluent families. Nuns who came from lesser means were expected to do more arduous labor as part of their religious life.

Nuns who committed themselves to the highest scholarship were treated as equals to men of their social rank. Honored as heads of an abbey, they had more power than their female contemporaries. ...

Among the earliest nun scholars was Juliana Morell, a 17th-century Spanish Dominican nun who is believed to be the first woman in the Western world to earn a university degree. Born in Barcelona on February 16, 1594, Morell was a young prodigy, and her distinguished banker father encouraged her to obtain the highest education, according to a 1941 article by S. Griswold in Hispanic Review (Vol. 9, No. 1).

A few years after Morell’s mother died, her father fled with his then seven-year-old daughter to Lyon, France, to escape murder charges. It was there that Morell continued her education, learning a variety of disciplines: Latin, Greek, Hebrew, mathematics, rhetoric as well as law and music.

When she was 12, Morell publicly defended her theses on logic and morality. She continued enriching her education by studying civil law, physics and canon, and soon after in Avignon, defended her law thesis in front of distinguished guests of the papacy.

Although it’s not known which body granted Morell her degree, she received a law doctorate in 1608 at the age of 14. In the fall of that year, Morell entered a Dominican convent in Avignon and three years later, took her final vows in the summer of 1610, eventually rising to the rank of a prioress.

Sister Juliana Morell.

The first university (allegedly) that was open to women was the University of Bologna, the first university in the Western world, which allowed women to study, earn degrees and teach since its foundation in 1088. The first verifiable and recorded instance of this occurring is at the same institution in 1239 when Bettisia Gozzadini teaches Law at the University of Bologna.

In our part of the world New Zealand admitted women to its universities in 1871 while Australia took until 1880 and even then those who earned a degree could not, unless they were teachers, legally earn a living by it until the 1918 Legal Womens Status Bill passed.

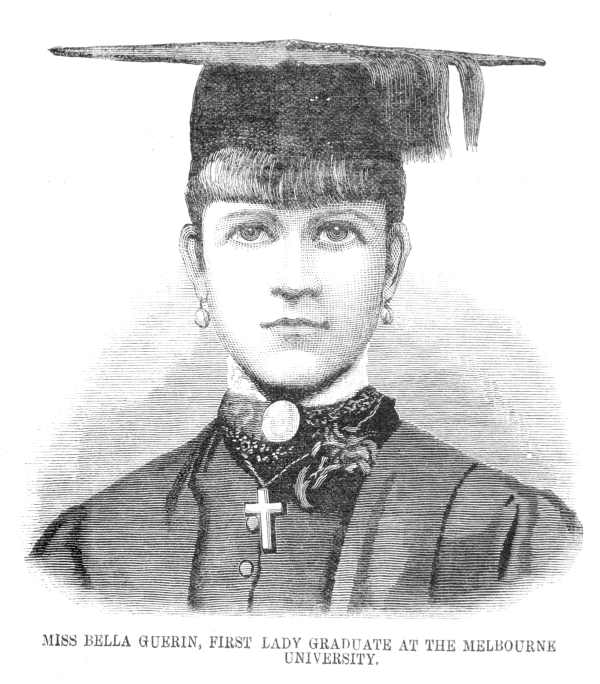

Julia Margaret Guerin, known as Bella Guerin, became the first woman to graduate from a university in Australia, when she graduated from the University of Melbourne in 1883.

After graduating Bella worked as a teacher, firstly at Loreto College, Ballarat where apparently she was often criticised by colleagues for being too proud of her degree.(3) Later Bella worked at the Ballarat School of Mines as Principal of Matriculation. Her contribution to the School of Mines was honoured in 1975 when a hall at the University of Ballarat was named after her. When she married in 1891, to poet Henry Halloran, she left teaching. However, shortly after the birth of her son, her husband died, leading to a return to teaching for financial necessity.

Beyond her role as a teacher she was also very active politically, as a campaigner for women’s rights and suffrage as well as being involved with the labor movement and anti-conscription campaigns during World War I. She co-authored Vida Goldstein’s 1913 senate election pamphlet and was also vice-president of the Women’s Political Association (1912-1914) and the Labor Party’s Women’s Central Organizing Committee (1918). She was, however, critical of the role of women within the Labor party, and in her 1918 speech ‘Women in the Labor Party: Poodle or Packhorse?’, she argued that women were only involved with fundraising and under-represented in policy decisions.

Bella Guerin died in Adelaide on the 26 July 1923. - Debra Hutchinson, Librarian, Australian History & Literature Team. July 10, 2013

In 1881 The University of Sydney Senate voted unanimously to allow women into the school. The Univesrity had first accepted students, who could only be male, in 1852. In 1882 two women, Mary Brown and Isola Thompson, enrolled in the Faculty of Arts. They graduated in 1885 and Isola went on to get her Masters in 1887.

There were many fine minded and intelligent women who graduated from Sydney University with Pittwater connections.

Visit: Marie Byles and Lucy Gullett

Illuminated manuscripts

An illuminated manuscript is a manuscript in which the text is supplemented with such decoration as initials, borders (marginalia) and miniature illustrations. In the strictest definition, the term refers only to manuscripts decorated with either gold or silver; but in both common usage and modern scholarship, the term refers to any decorated or illustrated manuscript from Western traditions. Comparable Far Eastern and Mesoamerican works are described as painted. Islamic manuscripts may be referred to as illuminated, illustrated or painted, though using essentially the same techniques as Western works.

The earliest extant substantive illuminated manuscripts are from the period 400 to 600, produced in the Kingdom of the Ostrogoths and the Eastern Roman Empire. Their significance lies not only in their inherent artistic and historical value, but also in the maintenance of a link of literacy offered by non-illuminated texts. Had it not been for the monastic scribes of Late Antiquity, most literature of Greece and Rome would have perished. As it was, the patterns of textual survivals were shaped by their usefulness to the severely constricted literate group of Christians. Illumination of manuscripts, as a way of aggrandizing ancient documents, aided their preservation and informative value in an era when new ruling classes were no longer literate, at least in the language used in the manuscripts.

The majority of extant manuscripts are from the Middle Ages, although many survive from the Renaissance, along with a very limited number from Late Antiquity. The majority are of a religious nature. Especially from the 13th century onward, an increasing number of secular texts were illuminated. Most illuminated manuscripts were created as codices, which had superseded scrolls. A very few illuminated fragments survive on papyrus, which does not last nearly as long as vellum or parchment. Most medieval manuscripts, illuminated or not, were written on parchment (most commonly of calf, sheep, or goat skin), but most manuscripts important enough to illuminate were written on the best quality of parchment, called vellum.

Jewish Illuminated manuscript of the Haggadah for Passover (14th century).

Beginning in the Late Middle Ages, manuscripts began to be produced on paper. Very early printed books were sometimes produced with spaces left for rubrics and miniatures, or were given illuminated initials, or decorations in the margin, but the introduction of printing rapidly led to the decline of illumination. Illuminated manuscripts continued to be produced in the early 16th century but in much smaller numbers, mostly for the very wealthy. They are among the most common items to survive from the Middle Ages; many thousands survive. They are also the best surviving specimens of medieval painting, and the best preserved. Indeed, for many areas and time periods, they are the only surviving examples of painting.

Art historians classify illuminated manuscripts into their historic periods and types, including (but not limited to) Late Antique, Insular, Carolingian manuscripts, Ottonian manuscripts, Romanesque manuscripts, Gothic manuscripts, and Renaissance manuscripts. There are a few examples from later periods. The type of book most often heavily and richly illuminated, sometimes known as a "display book", varied between periods. In the first millennium, these were most likely to be Gospel Books, such as the Lindisfarne Gospels and the Book of Kells. The Romanesque period saw the creation of many large illuminated complete Bibles – one in Sweden requires three librarians to lift it. Many Psalters were also heavily illuminated in both this and the Gothic period. Single cards or posters of vellum, leather or paper were in wider circulation with short stories or legends on them about the lives of saints, chivalry knights or other mythological figures, even criminal, social or miraculous occurrences; popular events much freely used by story tellers and itinerant actors to support their plays. Finally, the Book of Hours, very commonly the personal devotional book of a wealthy layperson, was often richly illuminated in the Gothic period. Other books, both liturgical and not, continued to be illuminated at all periods.

The Byzantine world produced manuscripts in its own style, versions of which spread to other Orthodox and Eastern Christian areas. The Muslim World and in particular the Iberian Peninsula, with their traditions of literacy uninterrupted by the Middle Ages, were instrumental in delivering ancient classic works to the growing intellectual circles and universities of Western Europe all through the 12th century, as books were produced there in large numbers and on paper for the first time in Europe, and with them full treatises on the sciences, especially astrology and medicine where illumination was required to have profuse and accurate representations with the text.

The Gothic period, which generally saw an increase in the production of these artifacts, also saw more secular works such as chronicles and works of literature illuminated. Wealthy people began to build up personal libraries; Philip the Bold probably had the largest personal library of his time in the mid-15th century, is estimated to have had about 600 illuminated manuscripts, whilst a number of his friends and relations had several dozen.

Up to the 12th century, most manuscripts were produced in monasteries in order to add to the library or after receiving a commission from a wealthy patron. Larger monasteries often contained separate areas for the monks who specialized in the production of manuscripts called a scriptorium. Within the walls of a scriptorium were individualized areas where a monk could sit and work on a manuscript without being disturbed by his fellow brethren. If no scriptorium was available, then “separate little rooms were assigned to book copying; they were situated in such a way that each scribe had to himself a window open to the cloister walk.” The separation of these monks from the rest of the cloister indicates just how revered these monks were within their society.

.jpg?timestamp=1547762739191)

The marriage of Girart to Bertha from the Roman de Girart de Roussillon, c. 1450

By the 14th century, the cloisters of monks writing in the scriptorium had almost fully given way to commercial urban scriptoria, especially in Paris, Rome and the Netherlands. While the process of creating an illuminated manuscript did not change, the move from monasteries to commercial settings was a radical step. Demand for manuscripts grew to an extent that Monastic libraries began to employ secular scribes and illuminators. These individuals often lived close to the monastery and, in instances, dressed as monks whenever they entered the monastery, but were allowed to leave at the end of the day. In reality, illuminators were often well known and acclaimed and many of their identities have survived.

.jpg?timestamp=1547762497357)

Illuminated manuscripts housed in the 16th-century Ethiopian Orthodox church of Ura Kidane Mehret, Zege Peninsula, Lake Tana, Ethiopia - photo by Katie Hunt from St Albans, UK

First, the manuscript was “sent to the rubricator, who added (in red or other colors) the titles, headlines, the initials of chapters and sections, the notes and so on; and then – if the book was to be illustrated – it was sent to the illuminator.” In the case of manuscripts that were sold commercially, the writing would “undoubtedly have been discussed initially between the patron and the scribe (or the scribe’s agent,) but by the time that the written gathering were sent off to the illuminator there was no longer any scope for innovation.”

Paints

The medieval artist's palette was broad; a partial list of pigments is given below. In addition, unlikely-sounding substances such as urine and earwax were used to prepare pigments.

Red

Insect-based colors, including:

- Carmine, also known as cochineal, where carminic acid from the Dactylopius coccus insect is mixed with an aluminum salt to produce the dye;

- Crimson, also known as kermes, extracted from the insect Kermes vermilio; and

- Lac, a scarlet resinous secretion of a number of species of insects.

- Red lead, chemically lead tetroxide, Pb3O4, found in nature as the mineral minium, or made by heating white lead;

- Vermilion, chemically mercury sulfide, HgS, and found in nature as the mineral cinnabar;

- Rust, chemically hydrated ferric oxide, Fe2O3·n H2O, or iron oxide-rich earth compounds.

Yellow

Plant-based colors, such as:

- Weld, processed from the Reseda luteola plant;

- Turmeric, from the Curcuma longa plant; and

- Saffron, rarely due to cost, from the Crocus sativus.

- Ochre, an earth pigment that occurs as the mineral limonite; and

- Orpiment, chemically arsenic trisulfide, As2S3.

- Verdigris, chemically cupric acetate, Cu(OAc)2·(H2O)2, made historically by boiling copper plates in vinegar;

- Malachite, a mineral found in nature, chemically basic copper carbonate, Cu2CO3·(OH)2; and

- China green, a plant-based pigment extracted from buckthorn (Rhamnus tinctoria, R. utilis) berries.

Blue

Plant-based substances such as:

- Woad, produced from the leaves of the plant Isatis tinctoria;

- Indigo, derived from the plant Indigofera tinctoria; and

- Turnsole, also known as folium, a dyestuff prepared from the plant Crozophora tinctoria.

- Ultramarine, made from the minerals lapis lazuli or azurite; and

- Smalt, now known as cobalt blue.

White lead, chemically basic lead carbonate, 2PbCO3·Pb(OH)2, and historically made by corroding sheets of lead with vinegar, and covering that with decaying matter, such as dung, to provide the necessary carbon dioxide for the chemical reaction; and

Chalk, chemically calcium carbonate, CaCO3.

Black

- Carbon, from sources such as lampblack, charcoal, or burnt bones or ivory;

- Sepia, from the ink produced by the cuttlefish, usually for an escape mechanism; and

- Iron gall ink, where in medieval times iron nails would be boiled in vinegar;

- the resulting compound would then be mixed with an extract of oak apple (oak galls).

Gold

Gold leaf, gold hammered extremely thin, or gold powder, bound in gum arabic or egg; the latter is called shell gold.

Silver

- Silver, either silver leaf or powdered, as with gold; and

- Tin leaf, also as with gold.