July 30 - August 5, 2023: Issue 592

Ringtail Posse 6: July 2023

Sonja Elwood: Long-Nosed Bandicoot, Dr. Conny Harris: Swamp Wallaby, Neil Evers: Bandicoot, Bill Goddard: Bandicoot

Definition from

Ringtail: from the 'Common Ringtail Possum' which is not so common anymore in urban areas. The Common Ringtail Possum is found along the entire eastern part of Australia and south west Western Australia. They are also found throughout Tasmania. The western ringtail possum is a threatened species under State and Commonwealth legislation. In Western Australia the species is listed as Critically Endangered fauna under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016.+

Posse: noun. 1 : a large group often with a common interest 2 : a body of persons summoned by a sheriff to assist in preserving the public peace usually in an emergency 3 : a group of people temporarily organised to make a search (as for a lost child) 4 : one's attendants or associates.

On Wednesday June 21st 2023 a Motion regarding Heritage Protection was passed in the NSW Parliament. Tabled by The Hon. Peter Primrose, contributors to the discussion spoke of the Minns Government's commitment to developing the State's first heritage strategy, in which the Government will develop options to recognise and protect significant trees, urban bushland and wildlife corridors.

This was, of course, music to the ears of all who are working at ground level in these areas to safeguard the survival of the urban wallaby, koala, lizard, skink, snake, bandicoot, every bird of woodland, water and grassland, insects and every other wildlife species we share suburbia with.

In recent approved DA’s Council is listing as a requirement of consent in Assessment reports to look after the other residents of this area, the wildlife. On blocks where people wish to remove large amounts of trees that are clearly homes for local fauna a wildlife expert must assess these prior to any removal taking place, nesting boxes are required to be installed afterward and Ecologists must be on site during their removal.

Recent examples and instances are:

Bandicoot/Penguin (Avalon)

Long-nosed Bandicoots & Little Penguins – Best Practices for Residents

Residents are encouraged to follow a number of Best Practices to assist with the protection and management of the endangered populations of Long-nosed Bandicoots and Little Penguins:

Long-nosed Bandicoots, Little Penguins and other native animals should never be fed as it may cause them nutritional problems, hardship if supplementary feeding is stopped, and it may increase predation.

Feral cats or foxes should never be fed or food left out where they can access it, such as rubbish bins without lids or pet food bowls, as these animals present a significant threat to Long-nosed Bandicoots, Little Penguins and other wildlife.

The use of insecticides, fertilisers, poisons and/or baits should be avoided on the property.

Garden insects will be kept in low numbers if Long-nosed Bandicoots are present.

When the North Head Long-nosed Bandicoot Recovery Plan is released it should be implemented where relevant.

Dead Long-nosed Bandicoots or Little Penguins should be reported by phoning Manly Council on 9976 1500 or Department of Environment and Conservation on 9960 6266.

Please drive carefully as vehicle related injuries and deaths of Long-nosed Bandicoots and Little Penguins have occurred in the area. Care should also be taken at night in the drive way when moving cars as bandicoots will seek shelter beneath vehicles.

Cat/s and or dog/s that currently live on the property should be kept indoors at night to avoid disturbance/death of native animals. Ideally, when the current cat/s and/or dog/s that live on the property no longer reside on the property it is recommended that they not be replaced by new dogs or cats.

Report all sightings of feral rabbits, feral or stray cats and/or foxes to N B Council.

And;

Protection of Habitat Features

All natural landscape features, including any rock outcrops, native vegetation and/or watercourses, are to remain undisturbed during the construction works, except where affected by necessary works detailed on approved plans.

Reason: To protect wildlife habitat.

The Reason given in all instances is: To protect native wildlife.

This follows on from the 2022 Local Government NSW Conference where a Motion was passed - That Local Government NSW lobby the NSW Government to:

- In conjunction with industry associations, introduce enforceable standards for the preparation of flora and fauna management plans.

- Consider Codes of Practice and Guidelines for handling native wildlife and other best practice and animal welfare laws in development of the standards.

- Consult with Councils, National Parks and Wildlife Service, Ecological Consultants Association of NSW, wildlife rescue organisations and other relevant agencies in the preparation of standards.

Such a standard should include requirements for:

- Pre-clearance surveys to be carried out to establish which species are present on the site, including identification of any threatened and native species.

- The identification of suitable nearby areas where wildlife could possibly be relocated.

- The provision of possum, glider and bat boxes sufficiently in advance of vegetation clearing to allow wildlife time to discover the boxes and become familiar with them.

- Compliance with the NSW Code of Practice for Injured, Sick and Orphaned Protected Fauna and the licencing requirements contained in the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016.

- Best practice for wildlife handling and care (including contact with local wildlife rescue groups).

- Reporting of injured or killed fauna to the NSW Department of Planning, Industry and Environment to enable the data to be used in statewide biodiversity monitoring programs.

The premise of this is that mandatory pre-clearance surveys to establish what wildlife lives there before works commence, and to document this in a formal way, should be required on any site that has vegetation and for which a DA has been approved. The experience is that often vegetation is removed before an application is submitted, often leaving wildlife with no home. Wildlife then ends up on roads dead or dies after being displaced/evicted.

One wildlife carer cited a recent Pittwater case of a powerful owl pair site that had had vegetation removed to make the development more likely to proceed – the nest and two babies were destroyed.

‘It’s hard to prove wildlife is/was present after the clearing as they aren’t there.’

‘Once trees and vegetation are removed the problem is where do these animals go?’

Powerful Owls are also not so common anymore in urban areas.

However it's clear human residents of this LGA have a deep and abiding love for and connection to these other furry, scaled, finned and feathered locals. We listen for them during the night, happy when we hear their footsteps scampering across our rooves and fences or their soft hoots across the valleys.

We look out for them during the day, delighted with their presence.

Residents here are distressed when they find injured wildlife or witness wildlife being attacked. They are not in denial that all our local wildlife feels and thinks - they cry when their babies are killed in front of them, mourn the loss of a mate - people who have heard or seen this never forget.

Data kept by the NSW Environment Department, although only listing incidents from June 2013 to June 30 2021, shows that 33,391 wildlife animals have been rescued in our area between June 2013 and June 30 2021 and just 8, 812 released again. Of these 42 were threatened species.

Data to 30 June 2021 lists of the 5, 235 animals rescued during that 2020 to 2021 period just 1,573 were released. Across NSW during that same year a total 120, 927 animals were rescued and just 28, 805 released - 5, 122 of these were were threatened species (104 kinds) of which just 1,180 were released.

These figures and data do not take into account all the wildlife found deceased beside or on roads or elsewhere.

''This study draws on 469,553 rescues reported over six years by wildlife rehabilitators for 688 species of bird, reptile, and mammal from New South Wales, Australia.... Of the 364,461 rescues for which the fate of an animal was known, 92% fell within two categories: ‘dead’, ‘died or euthanised’ (54.8% of rescues with known fate) and animals that recovered and were subsequently released (37.1% of rescues with known fate).''In total, there were 872,087 records reported during the six-year (2013–14 to 2018–19) study period. Just over 97% of these came from three animal groups–birds, mammals, and reptiles. Of the total number of records, 402,534, (46%) were excluded from the descriptive analysis because they: a) did not contain any information about the animal, or the animal’s identification was ambiguous and could not be placed within a group (e.g. an ‘unidentified animal’); b) contained only sightings of animals and were not attended to in some way by a wildlife rehabilitator; c) were records of amphibians (373 records) or non-vertebrate fauna (e.g. spiders, insects, etc.); d) were non-avian marine vertebrates such as whales, seals, sharks, rays, fish etc; e) were reported as floating, drowned, or washed up animals (deemed an ambiguous cause for rescue, n = 48); f) contained both an ‘unknown’ cause for rescue and an ‘unknown’ fate; or f) were an introduced or spurious species (e.g. extinct, or out of known range). These exclusions resulted in a dataset for descriptive analysis of 469,553 records i.e. 54% of the initially reported amount.''

Many people state we are the generation witnessing the extinction of urban wildlife. There has been generation after generation of humans living alongside and with wildlife, until this one.

It's not just the Pittwater koalas that have gone, other species, like the ringtail possum or long-nosed bandicoot are disappearing, along with their joyful snuffles and squeaks, from our urban backyards and the trees that tower over them.

There is a growing silence at night for those species that forage for food then - possums, wallabies, owls. The same is occurring for those that are active during daylight.

Although many point to the impacts of cat and dog attacks due to irresponsible owners, there is also what is termed the 'inconvenient possum' in a roof or garden shed, because its home tree has been cut down. These are caught by those hired, some of whom have little knowledge or scruples, and release them into areas out of their home range - a death sentence for that possum as this species is territorial, along with requiring certain food trees in order to eat, to survive.

There is predation by other introduced species - readers regularly send in photos and videos of foxes roaming and killing at night.

There are roadkill black spots, places where wallabies or turtles or possums used to cross the area where a road has been cut through and a speed limit that means death for wildlife. There are no 'speed humps' in place, and no plan at a local, state or federal government level to install these. Residents and wildlife rescuers have reported some drivers 'aiming straight for' a stricken animal.

There is the razing of blocks of land for development prior to any required assessment of the environment taking place to circumvent those requirements so a report can state 'nothing present'. There is nothing present because its habitat has been cleared or the wildlife killed by these actions.

Our local wildlife carers are exhausted, state there have been so many, too many so far this year - they are increasingly heartbroken with all the babies they lose, they cry every day, and then pick themselves up and get on with trying to save the next critter, and the next.

Wildlife carers are all volunteers - they do the rescues, sometimes horrific rescues, run to and fro from the great local vets who help out trying to save them, they gather or pay for the food, for the milk, for the petrol, for the electricity to keep bubs warm. There are no grants or funding for Australia's wildlife carers - they have to raise funds through running events, raising awareness, collecting cans for a 10 cent return.

This year a celebration of residents' favourite wildlife runs as Profiles across 2023 - simply to allow those who love a chosen 'critter' to speak for them a little, to remind us of what is here and what we feel connected to has feelings too.

Information about these species and how many or why we are losing them is included - just so we can think about how we, as individuals and as one community, can turn around that growing silent emptiness closing in around us and these other ones we love.

Ultimately the founders of the Ringtail Posse are hoping everyone chooses to become a Member of the Ringtail Posse and keep their other loved one safer in its one and only home.

Reason?: To Protect Local Wildlife so it becomes 'common' and safer for our wildlife to be everywhere once more.

To join in please email us with 'Ringtail Posse' in the subject line - with so many local species of wildlife, vital insects and seals flopping around on the sand or penguins flitting through the seas, there are several on the lists that haven't been claimed for guardianship yet - what's yours?

Round 6 of Ringtail Posse Profiles includes the following now officially joined Members:

Sonja Elwood

Founding Member of Sydney Wildlife Rescue (over 26 years ago), holds a Master of Research; Urban Ecology and Bandicoots, Master's Degree; Wildlife Management, Bachelor's Degree; Environmental Science, 21 years working in Environmental Project Officer and Biodiversity Officer roles with Pittwater Council and Northern beaches Council. Decades of experience in: Native and threatened fauna planning and management, pest species control, bushland management, community biodiversity education and events. Vice Chair, Media and Sydney representative of the NSW Wildlife Council (18 years), Rescuer and Carer and various management roles with WIRES (9.5 years). Involved in disaster response management, coordination and liaison for native fauna in the 2019/2020 black summer bushfires - it was Sonja that called in all the help agencies locally and those who came from overseas to do what they could.

In 2012 Sonja was named the Volunteer of the Year Award - 20 Years Plus, by Pittwater Council and this was followed up in February 2016 with a Staff recognition 'For exceptional performance project managing feral animal control programs across Pittwater'.

Currently Sonja is a Biodiversity Officer with Northern Beaches Council and still involved in community biodiversity tours and events.

Her passion has always been for saving wildlife though, telling Pittwater Online in her 2012 Profile;

'To my mother/grandmother’s horror when a toddler I would bring dead animals home that I found (birds or hedgehogs) and put them into the hot water cupboard in the belief if I could just warm them up they may come back to life.'

That preoccupation with saving the lives of the local fauna continued in Australia for years with WIRES before Sonja started Sydney Wildlife in 1997, a voluntary native animal rescue and rehabilitation service that operates 24 hours per day, 7 days per week. The organisation receives no government funding and is operated entirely by volunteers - dedicated angels who you can have a chat to at 2, 4 and 5 a.m. because they're up - feeding babies, changing dressings, rescuing another native animal from a road, a roof or a domestic pets' clutches.

What is you favourite local wildlife species?

The long-nosed bandicoot.

Why do you like the long-nosed bandicoot?

I love them because they’re so unusual and full of character and they’re little eco-engineers!

How long have seen or heard the long-nosed bandicoot?

Have them in my yard every night 😍🥰

Have you noticed any changes in the number of these animals in your local neighbourhood?

I'm deeply concerned their numbers are dwindling due to urban development intensification, loss of habitat, cars, cats and dogs, and an unfortunate bias some people have around the little holes they leave in your garden lawn (first world problem in my opinion) and the misnomer they bring ticks!

I feel the endangered population status currently over North Head should be extended over the whole of our LGA.

My photo - but how could you not love these little guys ❤️

Sonja at work - somewhere in our area

Dr. Conny Harris, MBBS

Dr Harris was born and educated in Germany, receiving medical degrees from the Universities of Freiberg and Hamburg. She has worked as a doctor in Germany, England, and Australia, and passed her Australian Medical Council Examination in 1995 and has worked in several Sydney hospitals, and began working at Mona Vale Hospital in the emergency department before setting up her practice as a General Practitioner in Dee Why in 2011. Conny also had the pleasure of experiencing medicine in remote Australia with The Flying Doctor Service.

In 2008, Conny was elected as Councillor and Deputy Mayor for Warringah.

An active member of Doctors for the Environment, Conny is a tireless community worker for causes ranging from healthy food canteens in schools, to responsible waste management, protection of the environment, reconciliation with Aboriginal Australia, improvements in public transport and traffic and much more.

Conny is a long-term activist in local community issues concerning bushland and wildlife, urban and non-urban development, improvement of health and waste reduction. She has a wide knowledge of local flora and fauna, especially eucalypts, and has lectured on this to the Australian Plant Society. She is also a member of the National Parks Threatened Species Committee. In 1999 she received a grant for educating local schoolchildren in native plant identification and bush regeneration.

She was director of the Manly Food Cooperative, from 1998-2002, and was appointed community representative on the Northern Region Waste Management Board in 2000. She founded the Garigal Landcare Group in 2001. Conny was also a founder of the Wildlife Roadkill Prevention Association, which aims to reduce the roadkill of native animals on the Northern Beaches of Sydney.

What is your favourite local wildlife species?

Well, that’s very hard – how can you have a favourite, they all go together.

I absolutely love the wallaby.

Why do you like the wallabies?

Because when you see them you see how big they can be, they are sweet, I love the joeys in the pouch. There are so many great things about the wallaby – their whole way of living, their behaviour, their curiosity – I think they are just gorgeous.

How long have seen or heard wallabies?

As soon as we moved here, which was on the 17th of January 1997.

Have you noticed any changes in the numbers of wallabies in your neighbourhood?

Oh yes, we have much less than we once did. Initially we had a great number but now, you’re lucky if you see one.

What do you think is leading to this loss of our local wallabies?

I think it’s a combination of factors; the roads of course are one that is leading to this as with the roads you see roadkill occurring. Then there are that lots of people have started using the local bush as their dog walking area and these dogs chase the wallabies and this is not good, especially for those having joeys in their pouch.

Photo: A young Warriewood Wetlands Wallaby by Kevin Murray, March 2022.

There have been 808 kangaroos and wallabies rescued in this area during the data period collated from June 2013 to June 2021 and just 40 released, the bulk of these swamp wallabies - 132 in the 2014/15 counts, 83 in the 2020/21 count. Road collisions is listed as the primary cause for rescues, as well as 'abandoned/orphaned' joeys - those in pouches when the mother is hit by a car and those 'thrown' when a mother is being chased by a dog and is trying to distract these and lead them away from the bay. This is why wallabies are not so 'common' in our area anymore either.

When dogs chase a wallaby for 'sport', the animal may escape but will develop stress myopathy, an irreversible, always fatal condition with no known treatment. Stress myopathy is a gradual breakdown of muscle tissue over a two-week period, causing increasing physical weakness until the wallaby is dragging itself around, a horrible way to die.

Renowned Australian writer Alan Marshall's 1939 short story 'The Grey Kangaroo' relates what happens when dogs chase wildlife or are introduced into their homes - there is no point pretending ignorance of these facts another generation or two on. That short story, as first run in 1939, runs below for those who have not yet read it.

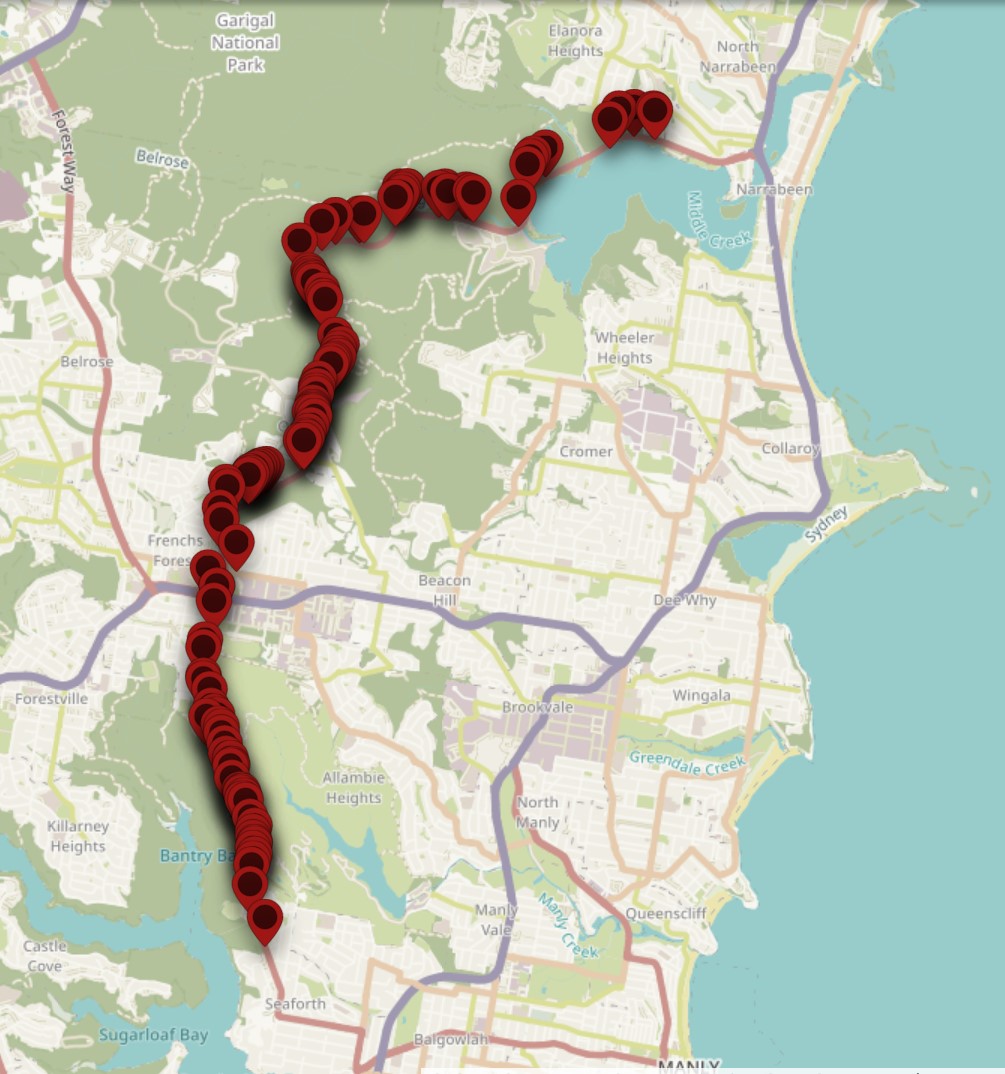

These statistics, probably only half of what is actually occurring according to the study cited above, do not take into account those that are killed. The Wildlife Roadkill Prevention members have been collecting data on this since being formed. This map marks the swamp wallaby roadkill on the Wakehurst Parkway for 2021 to 2023.

There are also large numbers that are being lost on Mona Vale road and associated back roads from Frenchs Forest down to Narrabeen and on towards Manly - their pathways, or wildlife corridor connections to other food places that have been in place through countless generations and are embedded in their genes.

An increase in roads and the resultant increase in cars through swamp wallaby habitats are a threat to their survival. They are frequently seen near the side of roads, leading to a larger number becoming roadkill.

Remember that if you hit an animal whilst driving always stop to see if the animal is still alive or if there is a joey in the pouch. If the animal is injured take it to a vet if you can, or call a local wildlife rescue group. When animals are killed, on our roads or elsewhere, there are often young who survive that need tender care to help them mature and eventually be released back into the wild.

A small army of local volunteers give up lots of time and plenty of sleep to act as surrogate mums providing shelter, food and attention so these babies may go back to their homes.

There are 2 rescue groups in the northern beaches are: Sydney Wildlife: 9413 4300 and WIRES: 1300 094 737.

The Swamp Wallaby (Wallabia bicolor), also known as the black wallaby or black pademelon, lives in the dense understorey of rainforests, woodlands and dry sclerophyll forest along eastern Australia. It was formerly found throughout south-eastern South Australia, but is now rare or absent from that region.

This unique Australian macropod has a dark black-grey coat with a distinctive light-coloured cheek stripe. The swamp wallaby is the only living member of the genus Wallabia.

The Swamp Wallaby becomes reproductively fertile between 15 and 18 months of age, and can breed throughout the year. Gestation is from 33 to 38 days, leading to a single young. The young is carried in the pouch for 8 to 9 months, but will continue to suckle until about 15 months.

Generally active from dusk until dawn, Swamp Wallabies are mostly solitary animals, but may gather to feed during the evening. It will eat a wide range of food plants, depending on availability, including shrubs, pasture, agricultural crops, and native and exotic vegetation. It appears to be able to tolerate a variety of plants poisonous to many other animals, including brackens, hemlock and lantana. The ideal diet appears to involve browsing on shrubs and bushes, rather than grazing on grasses. This is unusual in Swamp Wallabies as other macropods typically prefer grazing. Tooth structure reflects this preference for browsing, with the shape of the molars differing from other wallabies. The fourth premolar is retained through life, and is shaped for cutting through coarse plant material.

Neil Evers

Descendant of the Broken Bay Tribe of Bungaree, Member of the Aboriginal Support Group Manly Warringah Pittwater, J.P.

What is your favourite local wildlife species?

The bandicoot, or bin bin - Bin-bin is from the Kuringgai language. I’m an Aboriginal man from what is known as or called Guringai or Kuringgai country. There are many clans in Kuringgai country, Garigal being one of them which is our clan.

Why do you like the bandicoot?

They are very cute little animals, real characters – I love the noises they make when talking to each other. They’re great at keeping my lawn aerated and keeping the insects down as that is what they eat.

How long have seen or heard this animal?

For as long as I can remember. I was born in Collaroy over 80 years ago and raised in Mona Vale.

Have you noticed any changes in the number of these animals in your local neighbourhood?

Yes, there are far less than there were. Our little dog tries chasing them out of our yard at Newport. Fortunately, it’s too small, old and slow to catch them, but there seem to be a lot more cats and people allowing these out at night, and these may account for the loss of bandicoots here.

Southern Brown Bandicoot and Long-nosed Bandicoot, Northern Beaches, New South Wales. Photo: J J Harrison

Bill Goddard

The Goddard family, along with the Gonsalves and the Verrills, were among the first groups to settle permanently in Palm Beach in the early 1900s. During Covid, Bill Goddard explored his family’s history in extraordinary detail and using family and other resources gathered a veritable treasure-trove of photos reaching back to when his great-grandfather established a boat-building business in Lavender Bay in the 1890s. Later a branch of the family took their boat-building skills to Palm Beach settling around Waratah Road. They built Goddard’s Wharf on Snapperman Beach, now demolished and established a store that was a forerunner to Palm Beach Wines.

What is your favourite local wildlife species?

Bandicoots.

Why do you like bandicoots?

Because I have several around my garden and I find them to be very pretty.

How long have seen or heard bandicoots?

All of my life – I have lived here all my life.

Have you noticed any changes in the number of these animals in your local neighbourhood?

Yes – I have found several killed by cats recently in my yard on Bilgola Plateau. We’re definitely seeing less and less of them.

Our cameras also picked up a fox sneaking around the other night as well. So they’re up against foxes and cats out at night – it makes it very hard to understand how we will still have bandicoots here if that persists.

Southern brown bandicoot (Isoodon obesulus) and long-nosed bandicoot (Perameles nasuta), Northern Beaches, New South Wales. Photo: J J Harrison

There were 743 Bandicoots rescued over the whole of the June 2013 to June 2021 data period, and just 176 released. Of these 409 were Long-nosed bandicoots, 2 were Southern Brown bandicoots (eastern) and 332 are listed as 'unidentified'.

There were 94 Bandicoots (long-nosed: 64 - unidentified: 29) rescued during the 2020 to 2021 period alone, and just 34 released, so 60, at least, lost their lives - ' car collisions' and 'unsuitable environment' are listed as causes for rescues, however cat attacks on this species account for more numbers of bandicoots needing help than car collisions, and dog attacks are also making up a too high percentage of impacts on this species.

Wildlife rescuers and carers who are called to help lactating mothers often then spend days searching for where the nest may be as there are babies to be rescued and fed as well - they are not often successful.

Once again, this does not take into account all the many other bandicoots that are found deceased beside our roads or mauled beyond help in our urban yards.

Residents would know we are losing our local bandicoots - in a call out for information on if people had heard them going into the rounds of the Ringtail Posse answers from Balgowlah to Manly and all points north stated they had not heard them for a while. The family of bandicoots in the Pittwater Online yard that once thrived here has also not been heard for at least 2 years, although cats have been chased from the yard, hunting after dark, every night since.

Along with the long-nosed bandicoot this LGA was once home to the Southern Brown Bandicoot, however their population has been reduced to a critical level. We are most definitely losing or have lost the bulk of our bandicoots. As Ringtail Posse members have already stated - we need to drive so we don't kill our local wildlife and keep cats indoors at night and dogs away from where wildlife lives.

The NSW Department of Environment states the northern beaches from Manly to Palm Beach are one of the last strongholds for long-nosed bandicoots in the Sydney region. There are 2 significant populations: at Pittwater, and on the coast near Newport. Because it is cut off from other bandicoot populations by houses, a population of long-nosed bandicoots at North Head in Sydney Harbour National Park at Manly has been listed as endangered and was one of the first endangered population listings in New South Wales.

The Long-nosed bandicoot (Perameles nasuta) is around 31–43 cm in size and weighs up to 1.5 kg. It has pointed ears, a short tail, grey-brown fur, a white underbelly and a long snout. Its coat is bristly and rough. Gestation lasts 12.5 days, one of the shortest known of mammal species. The young spend another 50 to 54 days in the mother's pouch before being weaned.

The long-nosed bandicoot is a common prey item of the introduced red fox, and why residents are urged to report these when they see them. Report where and when at: https://www.feralscan.org.au/foxscan/default.aspx

Although the Dept. of Environment states this species is the most common species of bandicoot in the Sydney area, locals not hearing them anymore would point out they are not so common anymore.

Long-nosed Bandicoots are known to dig small, conical holes in lawns and gardens. Whilst bandicoot diggings can be unsightly, bandicoots are often helping the home gardener control grubs and garden pests. They eat insects, earthworms, insect larvae and spiders (including the venomous funnel-web spider) as well as tubers and fungi. Bandicoots are often attracted to forage on watered lawns and gardens where insect numbers are higher than in bushland, and these areas can sustain higher numbers of bandicoots.

Long-nosed Bandicoot, northern beaches, New South Wales. Photo: JJ Harrison

The Southern brown bandicoot (Isoodon obesulus) is listed as endangered in NSW. It is around 28–36 cm in size and weighs up to 1.5 kg. It has small, rounded ears, a longish, conical snout, a short, tapered tail and a yellow-brown or dark grey coat with a cream-white underbelly. They are smaller and shyer than other species and do not stray far from their preferred shelter of dense heath vegetation.

The southern brown bandicoot is patchily distributed and occurs south from the Hawkesbury River to the Victorian border and east of the Great Dividing Range.

There are 2 main populations; one lives in Garigal and Ku-ring-gai Chase national parks in northern Sydney - yet more reason to keep pets out of these places. The other lives around Ben Boyd National Park and Nadgee Nature Reserve in the far south-eastern corner of the state.

Southern brown bandicoots are nocturnal and omnivorous, feeding on insects, spiders, worms, plant roots, ferns, and fungi. Gestation lasts less than fifteen days and typically results in the birth of two or three young.

The young weigh just 350 mg (5.4 gr) at birth, remain in the pouch for about the first 53 days of life, and are fully weaned at around 60 days. Growth and maturation is relatively rapid among marsupials, with females becoming sexually mature at four to five months of age, and males at six or seven months. Lifespan in the wild is probably no more than four years.

Populations have declined markedly and become much more fragmented in the time since European expansion on the Australian mainland, much of that due to the clearing of habitat. In many areas of its range the species is threatened locally, while it may be common where rainfall is high enough and vegetation cover is thick enough. Apart from habitat fragmentation, the species is under pressure from introduced predators such as the red fox and feral cats. It has been reintroduced to some lower rainfall areas where there is protection against cat and fox predation – one such site being Wadderin Sanctuary in the eastern wheatbelt of Western Australia, 300 km east of Perth.

In national assessment, the southern brown bandicoot is currently regarded as Endangered on the mainland as a whole, and Vulnerable in South Australia.

Juvenile southern brown bandicoot. Photo; Bertram Lobert

Bandicoots have at least 4 distinct vocalisations:

- a high-pitched, bird-like noise used to locate one another

- when irritated, they will make a 'whuff, whuff' noise

- when feeling threatened or alarmed, they will make a loud 'chuff, chuff' noise and loud whistling squeak at the same time

- when in pain or experiencing fear, they will make a loud shriek.

Activities to assist this species:

- Prevent domestic cats and dogs from roaming into habitat areas.

- Protect all known and potential habitat and include linkages across the broader landscape.

- Undertake fox, feral dog and feral cat control programs.

- Apply fire regimes that maintain patches of dense ground cover and floristic and structural diversity in the habitat.

The Grey Kangaroo

By ALAN MARSHALL

Of Caulfield

She knew the old prospector. From a cleared patch on the hillside she often noticed him wash-ins for gold in the creek that ran through the valley.

Sometimes he stopped his swirling and sat on the bank Watching her while he filled his pipe.

He had known her for two years. She was his friend. She was smaller than her companions, and differed from them in color. She was grey; they were almost black — "Scrubbers," the old man called them.

Each morning the creaking of his cart as he followed the winding track round the mountain side, would cause them, to stand erect for a moment, nostrils twitching.

But they did not fear him. He was one with the carol of the magpies and the gums.

When his "Whoa there !" stayed the old black horse, they knew he only wished to look at them. They continued feeding. Their movements were like music — rhythmical— an undulating rise and fall of symmetrical bodies against a background of slender trees.

Occasionally they stopped and, sitting upright, looked back at him, a look of intense interest, of watchfulness.

Their flanks, wet with the dew from sweet-smelling leaves, glistened in the morning sun. They seemed like children of the trees.

There was a day when the old prospector approached within a few yards of the grey kangaroo. She awaited his coming, standing with head extended, eyes half-closed, nostrils working with curiosity. He remained motionless, and they regarded each other.

She turned and hopped slowly away from him. She moved with grace and dignity, despite her burden. She carried a Joey.

A MILE from the spot where the old prospector worked, two boys were cutting timber. Their axe heads glittered in the sun. When for a moment the eager steel poised motionless above their heads, the muscles on their uncovered backs stood out in little, smooth, brown hills. Their skin had the unblemished gloss of egg shells.

Beside the log on which they worked lay a blue kangaroo dog. His powerful, rib-lined chest rose and fell. His narrow loins had the delicacy of a stem. Suddenly lie lifted his head and, turning, bit at the smooth hair on his shoulder to ease an irritation. His lips, pushed up and back, revealed red gums and the smooth, Ivory daggers of his teeth. He snuffled and worked his jaws. His jowls flowed with saliva. He expelled a deep breath and lay back again. Files hovered Over his head. He snapped and moved restlessly.

The boys called him Springer — Springer, the killer. In the shade from surrounding trees lay other dogs. They formed a pack, the existence of which was due to the boys' love of hunting. They had no beauty of line, as had Springer. They were a rabble. They barked at nights and howled at the moon. They ran down rabbits with savage joy and, in the pack, were relentless in their pursuit. They looked to Springer to bring down the larger game. They were content to be in at the kill.

One of them, Boofer, a half-bred sheep dog, rose and stretched herself. She yawned with a whine and walked into the sunlight. She stood there a moment meditatively. She looked back over her shoulder. A flying chip fell beside her. She sniffed It. She was bored. She turned and trotted off among the trees.

SOME time later her excited barking caused the other dogs to jump to their feet They stood with their necks erect, their heads moving alertly from side to side.

Boofer tore past, some distance away, running at speed, her nose to the ground. The dogs yelped with delight and, scattering dry gum leaves and crashing through scrub, sped after her.

The boys stopped work and watched.

"There they are up on the hill !" cried one. "Look, quick, look !"

He pointed.

He put two fingers to his mouth and whistled shrilly.

Springer, having disregarded the yelping of the pack, leaped to his feet at the sound, as to a clarion call.

He sprang forward with short, stiff bounds, craning his neck as if to see over obstacles. He stopped and grew tense, one forefoot raised in the air. His panting had ceased. He looked eagerly from side to side.

The boy who had whistled jumped from the log. He ran to the blue dog and, grasping his head between his hands, half lifted him from the ground. The dog's neck was stretched and rolls of skin half closed his eyes.

"See 'em. See 'em," he whispered excitedly.

But no responsive quickening of muscle stirred the dog. The boy ran forward dragging Springer with him.

Then Springer saw. With a mighty bound he parted the boy's hands. He leaped with a terrific releasing of energy, doubling like a spring until, having attained speed, he moved with effortless beauty.

The boy sprang again to the log. He stood with his lips slightly parted, eyes wide, his hands clenched by his sides.

"Boy!" he breathed to his companion. ''Look at him!''

UPON the hillside the mob of kangaroos had heard the yapping of Boofer on their trail. The little grey kangaroo lifted her head quickly. For a long, tense moment she stood in frozen immobility looking down into the valley. Her joey, nibbling at the grass some distance from her, jumped in sudden panic and made for his mother with single-purposed speed. With her paws she held her pouch open like a sugar bag. He tumbled in headlong, his kicking legs projecting a moment before he disappeared.

How safe he felt in there: how secure from dogs with teeth and men with guns. His little heart, swift-beating at the excited barking of the pack, became even and content. He turned and his head popped forth with childish curiosity.

His mother was already on the move. The does were in haste; the old men were more leisured.

With a clamor the pack broke through the trees. Ahead of them like the point of a spear, Springer ran silently.

The kangaroos leaped into frantic speed, but before they had gained their top, Springer was among them and they scattered wildly. Perhaps It was because of her conspicuous color, perhaps because she was so very small, the kangaroo dog singled her out from her companions and set after her relentlessly.

And, recognising his leadership, the pack followed, eagerly, joyfully, the hills echoing their exultation.

SHE had intended making up the hill to thicker timber, but, as if suddenly realising her desperate plight, and the heavy responsibilities of motherhood, she turned her flight towards the old prospector.

Through the fragrant hazel, past the mottled silver-wattles, by sad tree ferns and across chip-strewn clearings she sped; and behind her Springer cleared as she the fallen trunks, the scattered limbs, swerved as she did from the pointed stakes, flew wombat holes and trickling water courses with equal ease. He rode the air like Death Itself.

The clutch of some mimosa hampered the grey kangaroo. She lost ground. The blue dog gathered himself and sprang, but the rough takeoff spoiled his leap and he wobbled in mid-air. His teeth closed on the skin; of her shoulder, his body struck her. She staggered and collided with a sapling. The dog shot past her, scat-ring the moist earth with tearing feet.

With heroic endeavor the grey kangaroo recovered her balance, and in a violent, concentrated effort, she drew away from the dog, a tattered banner of red skin draggling from her naked shoulder.

She made for some crowded gum suckers. They brushed her as she passed. With a swift and desperate movement she tore her Joey from her pouch and flung him, almost without loss of speed, into their shelter. She turned at right angles, leading the blue dog away from him.

The joey, staggered to his feet and hopped away distractedly. But the following pack, with triumphant cries, bore down on him. He gave one helpless glance back at them and tried to flee. They swept over him like a wind. He was lost in their midst ...

Their howl of triumph reached the little grey mother as she strained ahead of Springer, the killer. Their unleashed savagery, fleeing from them in bloody glee, broke upon her in waves.

THE old prospector heard it, too, and dropping his dish, he clambered in clumsy haste from the creek. When his head and shoulders appeared over the bank, he stopped a moment with dazes eyes and open mouth watching the approach of the grey kangaroo and her pursuer.

He raised himself swiftly and ran towards them. His eyes were wide open, distraught. He raised his himself in the air and cried, hoarsely, "Come be'ind 'ere! Come be'ind 'ere!"

When the grey kangaroo reached the clearing she was all but spent. The blue dog, with mouth open and silken strands of saliva blowing free raced behind her across a patch of fern; was but a length away when with painful bounds, she reached the cool sweetness of young grass.

He made a last, terrific burst. He left the ground with all the glorious energy of a skin-clad dancer, his body modelled in clean curves of muscle. His teeth locked deep in her shoulder. His hurtling body seemed to arrest In speed as if suddenly braked. He met the ground stiff-legged and taut.

THE grey kangaroo, her head jerked downwards, spun in the air. She turned completely over. Her long tail whipped in a circle above her head. She landed with a dull crash on her back. Before the shock of her falling had released her breath, Springer was at her throat. With demoniac savagery he tore at the soft, warm fur. With braced forelegs and tail erect, he shook her in a frenzy.

She kicked helplessly.

He sprang back, keyed for further conflict.

Her front paws, like little hands, quivered in unconscious supplication. She relaxed, sinking closer to the earth as to a mother.

He turned and walked away from her, panting, with red drops dripping from his running tongue.

With half-closed eyes he watched the old prospector running towards them, his heavy, wet boots flop-flopping on the grass

TODAY'S SHORT STORY (1939, June 15). The Herald (Melbourne, Vic. : 1861 - 1954), p. 46. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article243469413

Bush Turkeys: Backyard Buddies Breeding Time Commences In August - BIG Tick Eaters - Ringtail Posse Insights

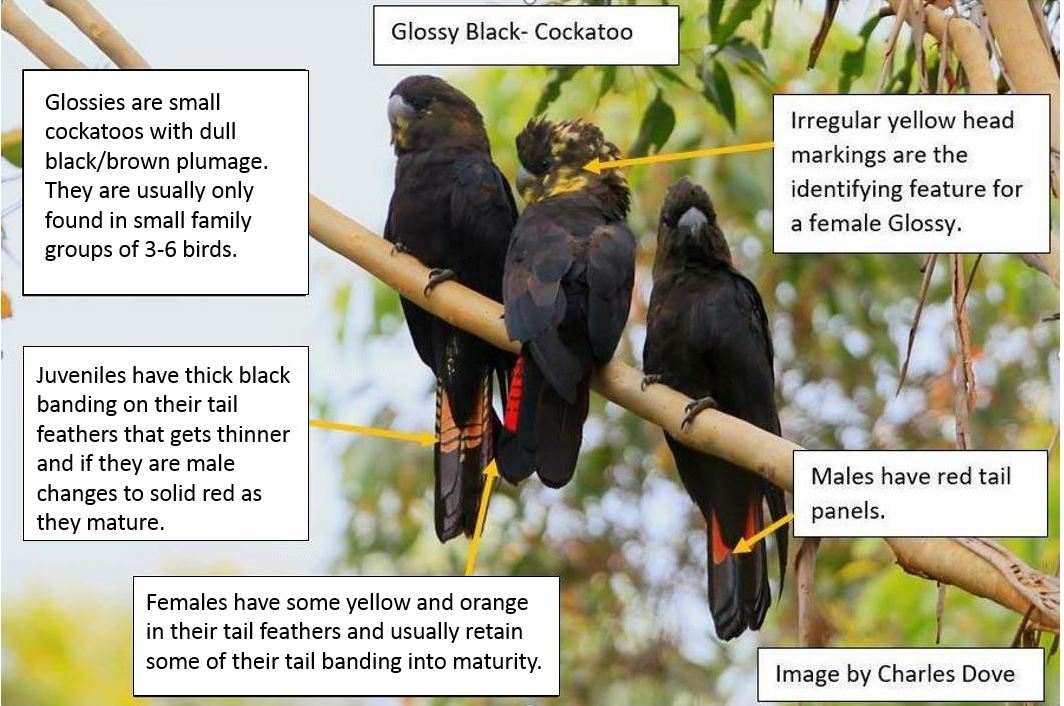

Seen Any Glossies Drinking Around Nambucca, Bellingen, Coffs Or Clarence? Want To Help: Join The Glossy Squad

- a female bird (identifiable by yellow on her head) begging and/or being fed by a male (with plain black/brown head and body and unbarred red tail feathers)

- a lone adult male, or a male with a begging female, flying purposefully after drinking at the end of the day.

- One-hundred brush-tailed mulgaras released onto Dirk Hartog Island

- Eighth species translocated as part of ground-breaking ecological restoration project

- Return to 1616 project is protecting populations of unique Western Australian wildlife

Endangered Dibblers Destined For Dirk Hartog Island National Park

- 24 Dibblers will be released at Dirk Hartog Island National Park for the first time

- Since 1997 over 900 Dibblers bred at Perth Zoo have been released into the wild

WA's New Strategy To Crackdown On Feral Cats In Nation First

- New five-year plan to manage invasive feral cats across Western Australia

- Strategy first of its kind to be implemented by a State Government in the nation

- $7.6 million investment to expand feral cat management in 2023-24 State Budget

- Fight against feral cats ramps up to protect native wildlife and biodiversity

Glide poles: the great Aussie invention helping flying possums cross the road

Next time you’re road-tripping along the east coast, keep an eye out for a little-known Aussie invention piercing the skyline: glide poles. For Australia’s gliding possums, or gliders, they’re the next best thing since tall trees.

These tall timber structures, with timber cross arms near the top, give gliders a way to cross big roads. They can shimmy up a pole on one side of the road and then leap to another (and another) to get to the other side.

After witnessing the earliest experiments with glide poles decades ago, it’s heartening to see the design refined and replicated up and down the east coast.

The world’s largest gliding marsupial, the greater glider, was listed nationally as endangered a year ago this month. That’s because their populations had declined by 80% in just 20 years. As land-clearing and bushfires continue to destroy old growth forests with tall trees and hollows, gliders need all the help they can get.

Biomimicry With Wooden Poles

From the match-box sized feathertail glider to the small cat-sized greater glider, Australia’s 11 species each have a gliding membrane, or patagium. This a thin area of skin stretching from the ankles to the wrists or hands.

When a glider leaps from a tree (or glide pole), it extends its front and hind limbs, stretching out its patagium, which allows it to glide.

In 1993 Ross Goldingay, one of Australia’s leading glider ecologists, came up with the idea of using tall wooden power poles (without wires) as road-crossing stepping-stones for gliders. The glide poles would act as substitutes for tall trees, so it was a very simple and elegant form of what’s known as “biomimicry”.

Ross directed the placement of glide poles on either side of a powerline easement at Bomaderry Creek near Nowra in southern New South Wales. The trial aimed to ensure yellow-bellied gliders could still cross the easement if it was developed into a local road.

Unfortunately, the Bomaderry Creek glide poles were never monitored. More than ten years later, a series of successful trials at Mackay and Compton Road in Brisbane demonstrated gliders would readily use glide poles. I recall showing Ross early images of squirrel gliders shimmying up the smooth, hardwood poles on the Compton Road land bridge soon after we installed cameras. We were blown away!

The poles needed to be tall enough to enable a comfortable glide crossing of the intervening gap. This is where trigonometry and the laws of physics come in, to get the calculations right for the species being targeted.

Since then, glide poles have become a fixture of upgrades along the Hume Highway in Victoria, the Pacific Highway in NSW and the Bruce Highway in Queensland.

Do The Poles Reconnect Glider Populations?

We are gradually gathering more evidence of glide pole use. Squirrel gliders, sugar gliders and feathertail gliders have been recorded using glide poles to cross roads at several locations.

Mahogany gliders, yellow-bellied gliders and southern greater gliders have also been recorded using glide poles.

Most notably, retrofitting a glider crossing into a road that previously presented a barrier to squirrel glider movement restored gene flow between populations on either side within five years.

Celebrating Some Of Australia’s Most Iconic Wildlife Crossings

Glide poles are one of many structures designed to provide safe road crossing opportunities for wildlife.

Pipes and box culverts can provide safe passage under the road, while land bridges and rope canopy bridges offer an alternative pathway over the road.

When combined with fencing, these structures reduce roadkill, provide access to resources on both sides of the road, and enable gene flow.

My new book combines an exploration of the how, when, where and why wildlife crossings evolved in eastern Australia with a travel guide to 57 of its most iconic sites.

The Road Ahead

We need to conserve, protect and restore our natural landscapes. This is especially the case in a rapidly changing climate. Our unique native species need to be able to move and adapt to the changing environment.

Carving up the landscape for road networks has been particularly bad for wildlife, with many populations becoming increasingly fragmented and increasingly isolated. But roads no longer need to act as roadblocks for the movement of many native species.

Engineers and ecologists have come together over recent years to find new ways to support the safe passage of animals from one side of the road to another. Their efforts deserve to be celebrated. Especially glide poles. They may not be as famous as the good old Hills Hoist clothesline, but they certainly deserve a gong as a great Australian invention. Certainly worth a nod when you pass by on your next great Aussie road trip.![]()

Brendan Taylor, Adjunct Research Fellow in the Faculty of Science & Engineering, Southern Cross University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.