November 16 - 22, 2014: Issue 189

The Compleat Angler - Izaak Walton Inspires Generations of Fisherfolk

The Compleat Angler - Izaak Walton’s Discourse Inspires Generations of Fishers

While researching in numerous places for the Pittwater’s Water Environs history pages, run recently here, numerous references were made to ‘The compleat angler or the contemplative man's recreation by Izaak Walton’ by the writers and compilers of facts we found for those pages.

A few weeks ago a copy of this work was discovered in a St Vincent’s Op Shop, much to our delight, and had for a small price in comparison to all it contains. Filled with Old English, this work transports you to an idyllic time and place and also gave a few insights into the origin of pen-names of some of the writers of fish and sailing columns in our own older and in some cases, defunct, newspapers.

The Compleat Angler was first published in 1653, but Walton continued to add to it for a quarter of a century. It is a celebration of the art and spirit of fishing in prose and verse; 6 verses were quoted from John Dennys's 1613 work The Secrets of Angling. It was dedicated to John Offley, his most honoured friend. There was a second edition in 1655, a third in 1661 (identical with that of 1664), a fourth in 1668 and a fifth in 1676. In this last edition the thirteen chapters of the original had grown to twenty-one, and a second part was added by his friend and brother angler Charles Cotton, who took up Venator where Walton had left him and completed his instruction in fly fishing and the making of flies.

Walton did not profess to be an expert with a fishing fly; the fly fishing in his first edition was contributed by Thomas Barker, a retired cook and humorist, who produced a treatise of his own in 1659; but in the use of the live worm, the grasshopper and the frog "Piscator" himself could speak as a master. The famous passage about the frog, often misquoted as being about the worm—"use him as though you loved him, that is, harm him as little as you may possibly, that he may live the longer"—appears in the original edition. The additions made as the work grew did not affect the technical part alone; quotations, new turns of phrase, songs, poems and anecdotes were introduced as if the author, who wrote it as a recreation, had kept it constantly in his mind and talked it over point by point with his many friends. There were originally only two interlocutors in the opening scene, "Piscator" and "Viator"; but in the second edition, as if in answer to an objection that "Piscator" had it too much in his own way in praise of angling, he introduced the falconer, "Auceps," changed "Viator" into "Venator" and made the new companions each dilate on the joys of his favourite sport. These names were adopted by Australian columnists during the 1800’s and early 1900’s – some of these overseeing not only fishing columns but those on sailing as well.

The work became so popular that hundreds of years later it was referred to here and also used as an acronym for other ‘compleat’ things – such as depicting ‘fishing’ politicians in that pun producing characteristic Australian witticism as ‘compleat fishermen’ too!

"The Compleat Angler."

WHEN Izaak Walton first published "The compleat Angler, or the Contemplative Man's Recreation," he ventured, in his foreword to the reader, to envisage the possibility that "this discourse which follows shall come to a second impression; for," he added he, "slight books have been in this age observed to have that fortune." That was nearly 300 years ago, and Walton's "slight book" is still finding new impressions. The latest (Black) is not the least covetable: for it is a facsimile of the original small octavo of 1653, with all Its details of paper, plate marking, and pagination, and with the same binding of brown sheepskin. It is an edition well designed "to find a place in the bulging pockets of anglers," but it is a treasure, not only for anglers, but for all book lovers. What makes "The Competent Angler" such an unfailing delight is its mingling of simplicity and wisdom, its genial humard artiste prde. Walton was careful to protest that, in writing his "discourse of fish and fishing," he made "a recreation of a recreation"; and so that his book might not "read dull and tediously," he had "in several places mixt some innocent Mirth." But he was none the less conscious of the dignity of his task as "a Brother of the Angle," discussing an Art "worthy the knowledge and practice of a wise and a serious man." It is pleasant to think of old Izaak, during all the fevers of the civil war, quietly fishing his favourite streams, and taking his catch to some "honest alehouse" to be dressed, where he might find "a cleanly room, Lavender in the windowes, and twenty Ballads stuck about the wall." There is no hint in these tranquil pages of the convulsions through which England was then passing. Viator and Piscator talk of many things as the pad it together over Totnam Hill; but they never mention the conflict between King and Parliament, and Piscator- antagonisms are reserved for such enemies as the Otter, and for "men of sowre complexions; monye-getttng-men that spend all their time first in getting, and next in anxious care to keep it"—"the poor-rich-men," as he calls them. It is not surprising that old Izaak made so many converts in the generations that have succeeded him. There is much to be learnt from his lore, if his natural history Is sometimes a thing to smile at. Chapter 10, for instance, which contains "several observations of the nature and breeding of Eeles," is a curious mixture of shrewd observation and childlike credulity. Yet Walton accepted conclusions that are still prevalent in the remoter parts of England. To dip into "The Compleat Angler" again is to be moved to cry Amen to its final invocation, of a blessing of St. Peter's Master "upon all that hate contentions, and love quietnesse and vertue and Ailing."—''Morning Post," London. "The Compleat Angler.". (1928, July 26). The Queenslander(Brisbane, Qld. : 1866 - 1939), p. 68. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article22951214

The best-known old edition of the Angler is J. Major's (2nd ed., 1824). The book was edited by Andrew Lang in 1896, followed by many other editions.

The version we have so recently acquired cost us a few gold coins and sells for around $10.00 elsewhere. A small amount of Googling shows other versions, due to their rarity or condition, as much as Edition, may fetch thousands of dollars.

To wit:

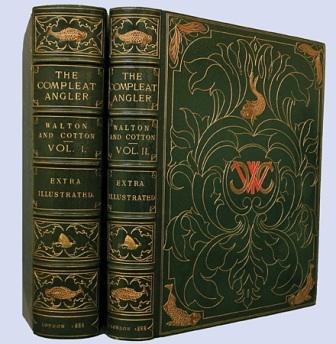

Izaak Walton and Charles Cotton. The Compleat Angler. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle and Rivington, 1888. - 2 vols. 4to, full polished dark green morocco decorated with the intertwined initials of the authors (in imitation of the emblem on the fishing cottage they shared) and other inlaid and gilt figures of fish and flies, gilt titles, marbled endpapers, by Morrell. Skillful repairs to joints, still a fine copy.

Izaak Walton and Charles Cotton. The Compleat Angler. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle and Rivington, 1888. - 2 vols. 4to, full polished dark green morocco decorated with the intertwined initials of the authors (in imitation of the emblem on the fishing cottage they shared) and other inlaid and gilt figures of fish and flies, gilt titles, marbled endpapers, by Morrell. Skillful repairs to joints, still a fine copy.

This is the Lea and Dove 100th edition of The Compleat Angler, extra-illustrated and containing Westwood and Satchell’s Chronicle of the Compleat Angler. Number 98 of 250 copies signed by editor R. B. Marston of The Fishing Gazette. An absolutely stunning binding and extremely important edition. Price: $ 25,000

Other p[rices and editions may be seen here - including a set of the first five editions for which the price is scheduled at US$ 125,000.00 - a good indication that some of us collect old books and First Editions because we want to hold them and read the originals while others are clearly collecting such works due to the investment they represent.

As with all old books knowledge of Editions, Publishers, the quality of the book or even whether it still has a dust jacket, is made from cloth or is leather bound - all this should be taken into consideration when considering collecting an old work for investment. Buying these from reputable dealers is also key.

Do you have books at home that may be worth thousands? A little wondering, a little researching is the only way you will find out.

Izaak Walton (c. 1594 – 15 December 1683) was an English writer. Best known as the author of The Compleat Angler, he also wrote a number of short biographies that have been collected under the title of Walton's Lives.

Izaak Walton (c. 1594 – 15 December 1683) was an English writer. Best known as the author of The Compleat Angler, he also wrote a number of short biographies that have been collected under the title of Walton's Lives.

Walton was born at Stafford c. 1594; the traditional '9 August 1593' date is based on a misinterpretation of his will, which he began on 9 August 1683. The register of his baptism gives his father's name as Gervase. His father, who was an innkeeper as well as a landlord of a tavern, died before Izaak was three. His mother then married another innkeeper by the name of Bourne, who later ran the Swan in Stafford.

He settled in London where he began trading as an ironmonger in a small shop in the upper storey of Thomas Gresham's Royal Burse or Exchange in Cornhill. In 1614 he had a shop in Fleet Street, two doors west of Chancery Lane in the parish of St Dunstan's.[2] He became verger and churchwarden of the church, and a friend of the vicar, John Donne.[1] He joined the Ironmongers' Company in November 1618.[1]

Walton's first wife was Rachel Floud (married December 1626), a great-great-niece of Archbishop Cranmer. She died in 1640. He soon remarried, to Anne Ken (1646–1662), who appears as the pastoral Kenna of The Angler's Wish; she was a stepsister of Thomas Ken, afterwards bishop of Bath and Wells.

After the Royalist defeat at Marston Moor in 1644, Walton retired from his trade. He went to live just north of his birthplace, at a spot between the town of Stafford and the town of Stone, where he had bought some land edged by a small river. His new land at Shallowford included a farm, and a parcel of land; however by 1650 he was living in Clerkenwell, London. The first edition of his book The Compleat Angler was published in 1653. His second wife died in 1662, and was buried in Worcester Cathedral, where there is a monument to her memory. One of his daughters married Dr Hawkins, a prebendary of Winchester.

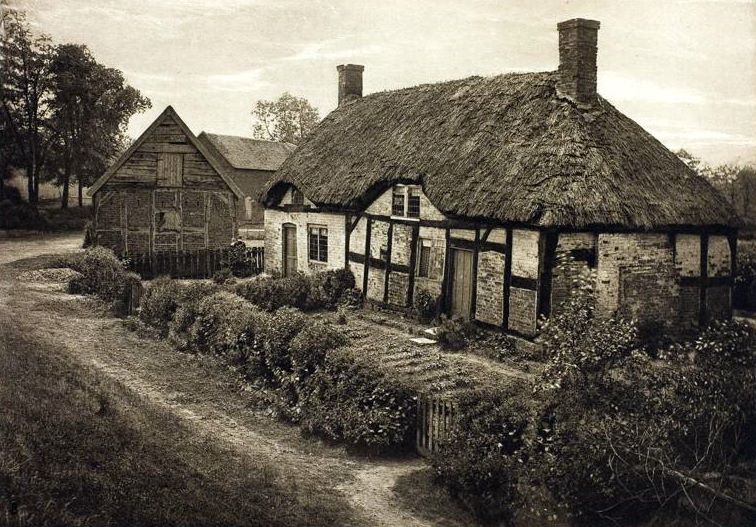

The last forty years of his life were spent visiting eminent clergymen and others who enjoyed fishing, compiling the biographies of people he liked, and collecting information for the Compleat Angler. After 1662 he found a home at Farnham Castle with George Morley, bishop of Winchester, to whom he dedicated his Life of George Herbert and his biography of Richard Hooker. He sometimes visited Charles Cotton in his fishing house on the Dove.Walton died in his daughter's house at Winchester, and was buried in Winchester Cathedral.

References:

Izaak Walton. (2014, September 25). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Izaak_Walton&oldid=626999351

Charles Cotton. (2014, September 7). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Charles_Cotton&oldid=624512651