This year’s whale season offered spectacular encounters with these majestic giants as thousands of whales migrated along Australia’s east coast.

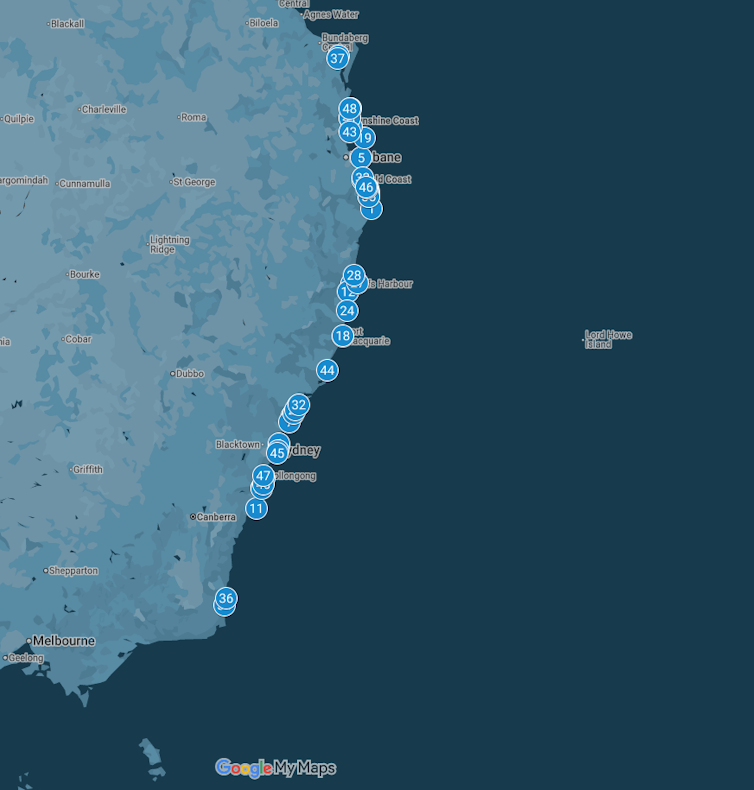

But behind the scenes, Australian scientists have noticed a troubling rise in the number of whales caught and tangled in ropes, nets and fishing lines. We documented 48 separate entanglements of humpback whales in the past few months on the east coast. This follows last year’s estimate of 45 entangled whales.

We collected this information from social media posts, newspaper articles and enquiries to authorities. Unfortunately, there is no official database, although we need one. The International Whaling Commission has voluntary reports on its portal.

Consistent with the increasing population size, entanglements of humpback whales in set fishing gear have been rising steadily since the 1990s. In 2017, for example, there were about 20.

Rising entanglements are part of a concerning trend seen in the United States and elsewhere. The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration confirmed 95 large whale entanglements in 2024, up 48% on the previous year.

Why do whales get tangled?

Humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) accounted for most of the large whale entanglements we recorded. Fishing gear such as nets and crab pots accounted for around 70% of these reported entanglements. The remainder are due to shark net programs, where gill nets and drumlines are placed along popular beaches to deter or catch sharks.

The biggest threats are posed by fishing gear with long lines or excessive rope in areas where whales feed and migrate. Whales more often get entangled in areas where fishing gear frequently changes locations. The highest numbers of entanglements were during the peak northern migration in June and peak southern migration in September.

Humpback populations are growing. But entanglements are not only due to increasing numbers of whales. Food shortages linked to faster Antarctic sea ice melt are forcing whales to feed in places where more fishing occurs.

What happens to entangled whales?

This whale season, we’ve been able to follow several individual entangled whales through reports from members of the public. In some cases, the same whale was seen over several weeks and thousands of kilometres apart.

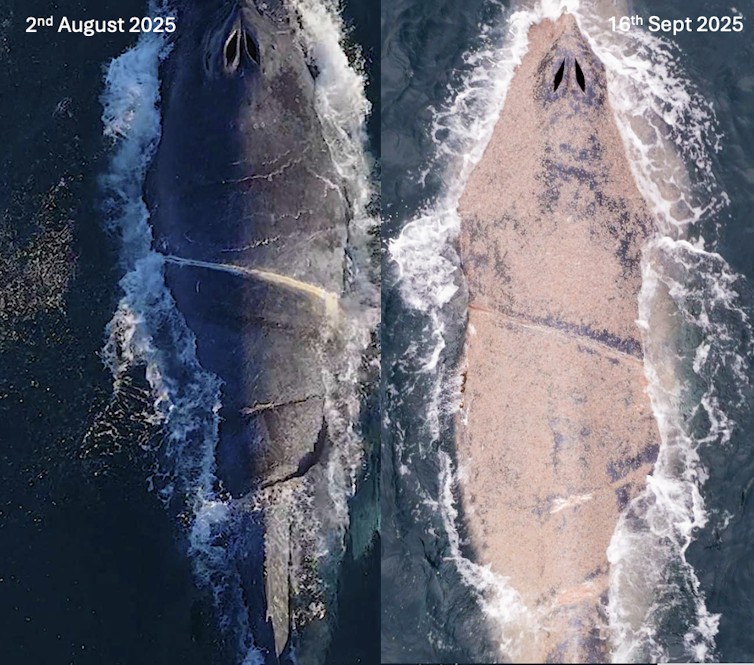

One humpback was first spotted in Hervey Bay on July 28 with thick rope around its body. On August 2, it was seen off the Gold Coast. By September 16, it was near Kiama in New South Wales. By then, the rope had finally come off. The whale’s health had severely declined. It had lost weight and was covered in sea lice – a sign of poor condition.

It’s most dangerous for a whale to be tangled in fishing gear with floats and long ropes, as these dramatically reduce its ability to swim and dive. To survive, it’s forced to use vital energy reserves. Shorter lines without floats can still be deadly, cutting deep into tail flukes or pectoral fins and causing painful wounds and infections. As their bodies weaken, whales often lose more than half their body weight, develop infections and become covered in sea lice.

Recovery after being entangled is possible if a whale remains strong enough to complete the migration and reach its feeding grounds. But the outlook is grim for many. Researchers found North Atlantic right whales entangled for several weeks often don’t survive.

How are whales freed?

This season, Australian rescue teams freed 18 whales. Most of these involved whales caught in gill nets and drumlines used in Queensland’s shark control program. Each release represents a remarkable effort from rescue teams.

Unfortunately, removal is no guarantee of survival. The damage may already be done. Survivors can suffer long-term consequences. Female whales that survive severe entanglement often fail to reproduce the following season.

On average, only a third of entangled whales are seen again after the initial report. Less than a quarter are disentangled.

Rescuing entangled whales is a delicate operation requiring expertise, specialised equipment and good weather.

Specialised teams such as the Sea World Foundation Rescue Team on Australia’s east coast and the NSW Parks and Wildlife Service Large Whale Disentanglement Teams are trained for these complex missions.

To free the whales, experts use specialised tools such as hooked knives on long poles, “flying” knives (attached to a rope and buoy), grappling hooks and large floats that can be attached to the tangled gear to slow the whale for a safer approach. Choosing the right ropes to cut, the right cutting location and the right order is crucial.

The success of a rescue depends on many factors, from sea condition to the whale’s behaviour, to the skill and coordination of the disentanglement team.

In many countries, members of the public are not permitted to attempt to free tangled whales. But as numbers of entanglements have grown, concerned Australians have mounted several dangerous rescue attempts, including people jumping onto whales to try and cut the lines. These ad hoc rescue missions can make the situation worse for the whale. If the wrong lines are cut, it can accidentally tighten others. These attempts can be life-threatening for rescuers.

What can we do better?

We need to get better at predicting the movements of entangled whales. By analysing migration patterns and ocean conditions, researchers could develop forecast tools to predict where an entangled whale might travel next, helping rescue teams intercept it more effectively. In some cases, attaching satellite trackers to the trailing gear has provided vital real-time data on a whale’s location and movement.

Better coordination between response groups is also essential. A centralised reporting system and data sharing across states and jurisdictions would help track incidents and whales, streamline rescue responses and strengthen research efforts.

The most important step is to prevent entanglements in the first place. To that end, we need to support the fishing industry to adopt safer practices, such as improving gear management and accountability.

Innovations such as ropeless fishing gear could cut the numbers of entangled whales. At present, they are expensive. Government incentives and shared investment could make these technologies more accessible.

If nothing is done, more whales will be entangled, and we will see more emaciated carcasses wash ashore.![]()

Olaf Meynecke, Research Fellow in Marine Science and Manager Whales & Climate Program, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.