June 12 -18, 2022: Issue 542

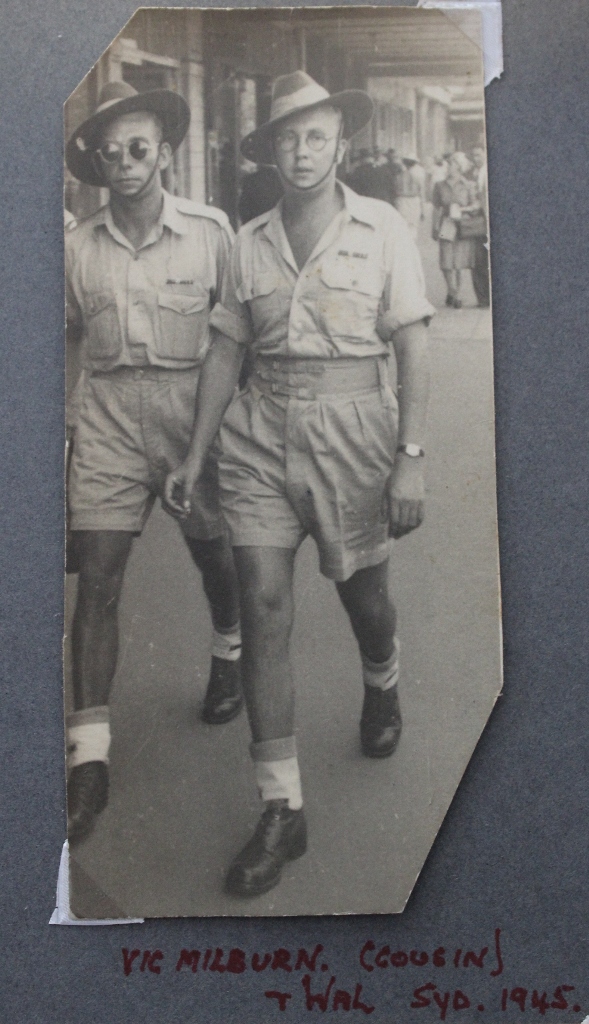

Walter (Wal) Williams OAM

VALE Wal Williams

10th October 1922 - 4th June 2022

It is our sad duty to inform this community that WW2 Veteran Wal Williams OAM has passed away.

Wal died on Saturday 4th June at Kokoda Hostel, War Veterans, Narrabeen, where he was a resident. Wal was a past President of Pittwater RSL Sub-Branch and a past Director of Pittwater RSL Club Ltd.

Wal was awarded his OAM on 14th June 2021 for his services to the Veteran Community.

Wal is survived by his son Neil, grandsons Robert and Nicholas, and great‑granddaughter, Sophia.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

It is our sad duty to inform this community that WW2 Veteran Wal Williams OAM has passed away.

Wal died on Saturday 4th June at Kokoda Hostel, War Veterans, Narrabeen, where he was a resident. Wal was a past President of Pittwater RSL Sub-Branch and a past Director of Pittwater RSL Club Ltd.

Wal was awarded his OAM on 14th June 2021 for his services to the Veteran Community.

Wal is survived by his son Neil, grandsons Robert and Nicholas, and great‑granddaughter, Sophia.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Tribute To Wal Williams OAM

In NSW Parliament, June 7, 2022 - by The Hon Rob Stokes, MP for Pittwater—Minister for Infrastructure, Minister for Cities, and Minister for Active Transport

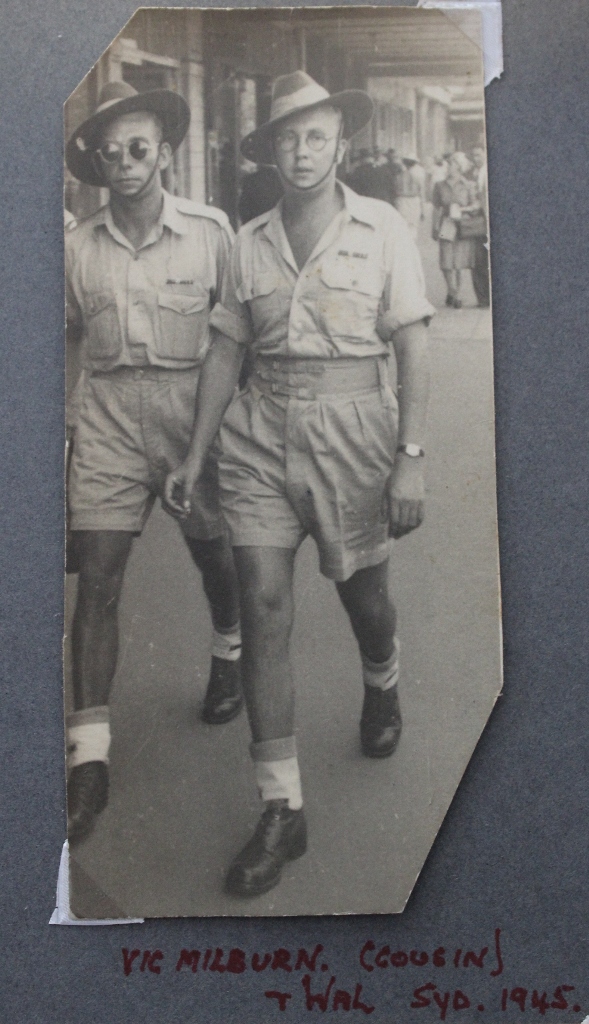

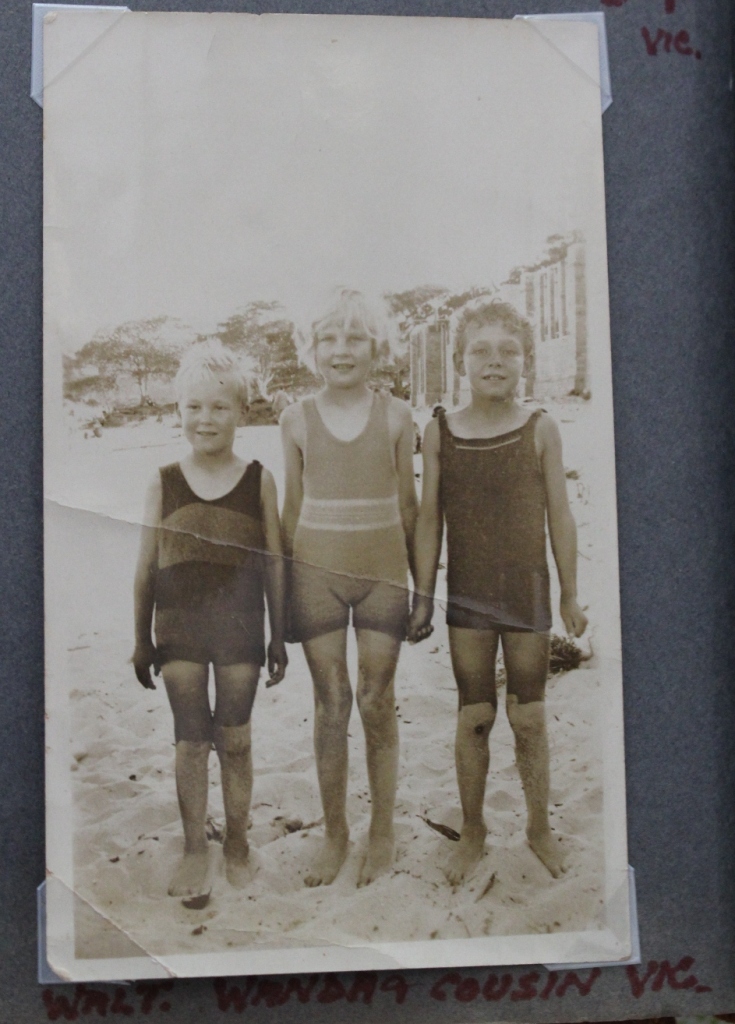

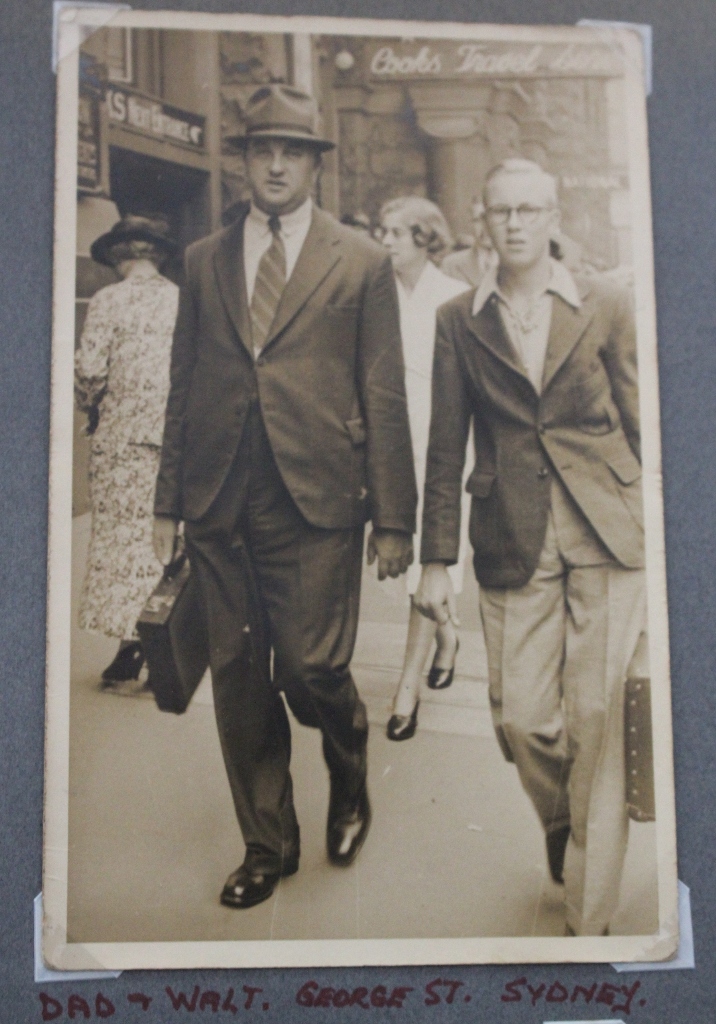

It is with a heavy heart that I acknowledge the life and legacy of Wal Williams, OAM. He was a World War II veteran who passed away on Saturday at the RSL ANZAC Village in Narrabeen at the age of 99. A local legend in Pittwater, Wal made a valuable contribution to raising awareness of the sacrifice and suffering of prisoners of war during the Second World War in the Pacific between 1941 and 1945. Born in Northbridge in 1922, Wal grew to be an excellent swimmer and represented the Northbridge Swimming Club at the NSW State Championships. This skill would later help save his life.

Not long after war broke out, Wal enlisted in the permanent army and then joined the Second Australian Imperial Force in November 1941. Wal was underage and needed permission to join up. His father, a Gallipoli veteran of the Light Horse, did not want Wal to be a soldier but eventually gave his permission.

In December 1941, following the Japanese attacks on Pearl Harbor and Malaya, Wal's unit sailed to Singapore to reinforce the 2/19th Battalion, which had suffered casualties just north of Singapore. In one of the strange quirks of history, the 2/19th was commanded by one of my ancestors, Lieutenant Colonel Charles Anderson. Together with his unit, Wal fought a fierce defensive battle for several days. Coinciding with heavy attacks elsewhere on the island's perimeter and on its water supply, and with supplies and ammunition dwindling, the difficult decision was made to surrender Singapore on 15 February 1942. Wal, along with tens of thousands of Allied soldiers, nurses and civilians, was taken prisoner. He would go on to spend three and a half years as a prisoner of the Japanese. At first interned at the infamous Changi prison camp, Wal was then put to work on the Burma‑Thailand Railway—with my uncle, Hugh Johnson—for two years, and would later be transported to Japan.

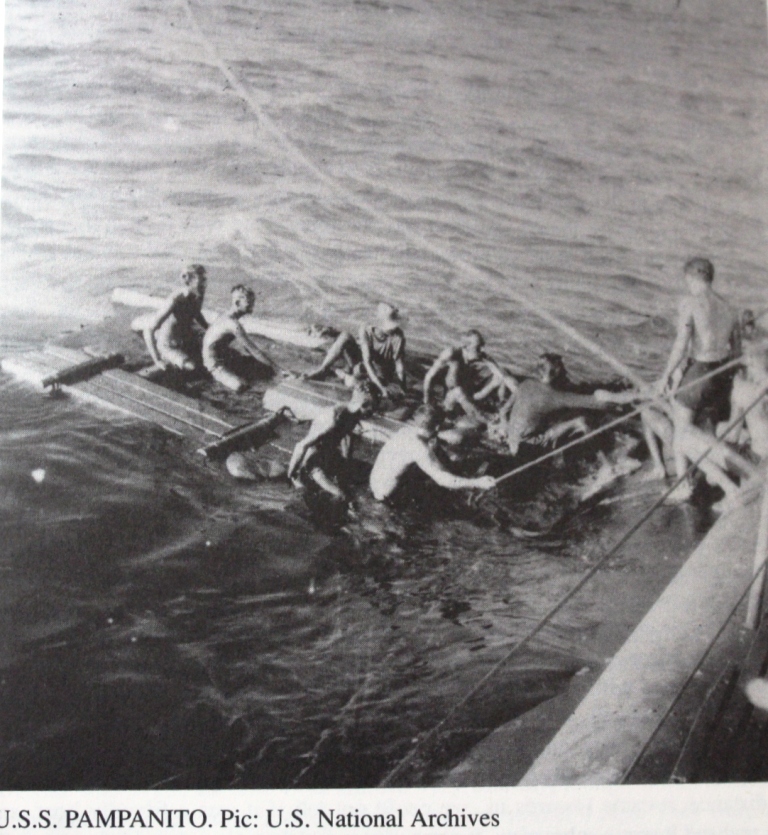

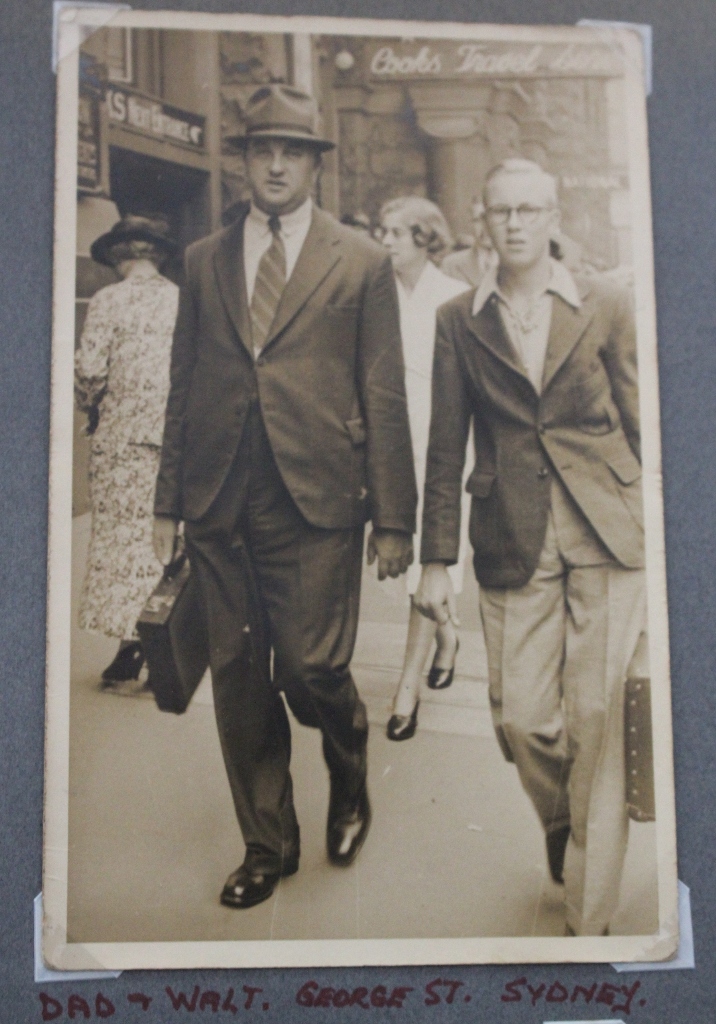

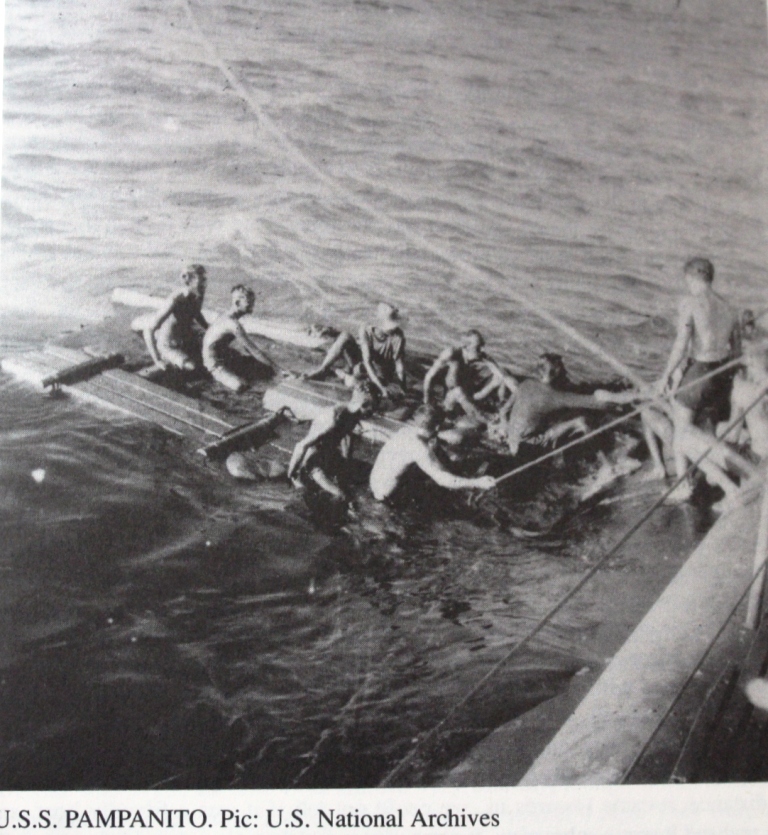

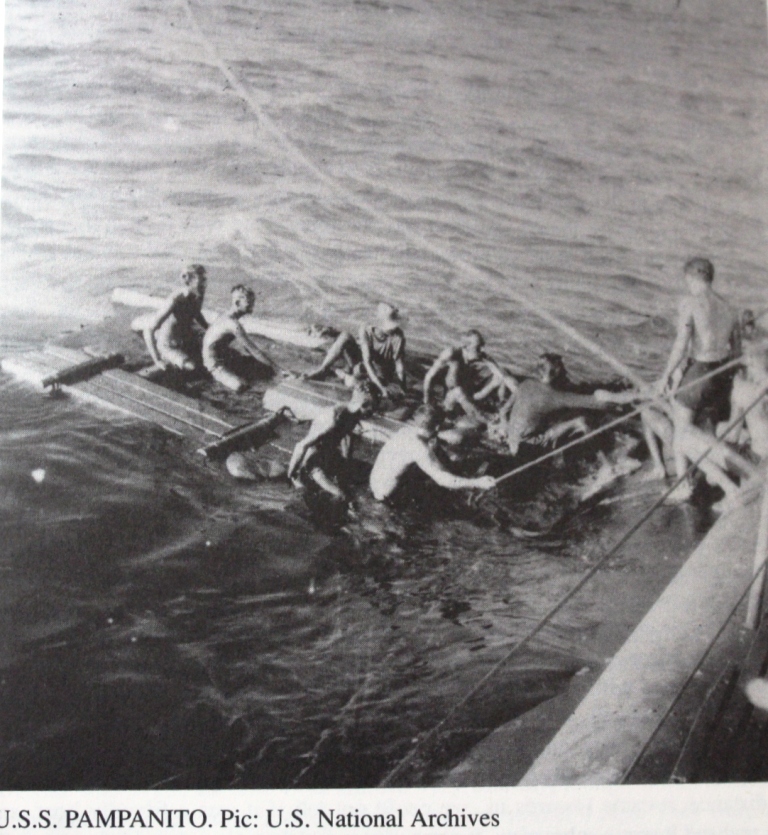

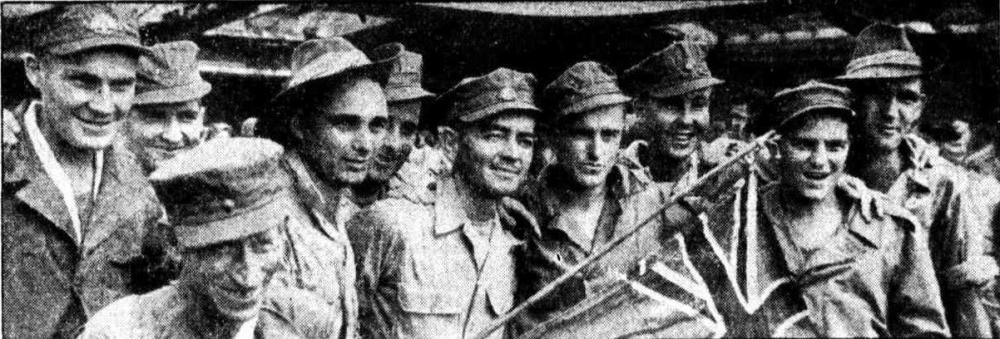

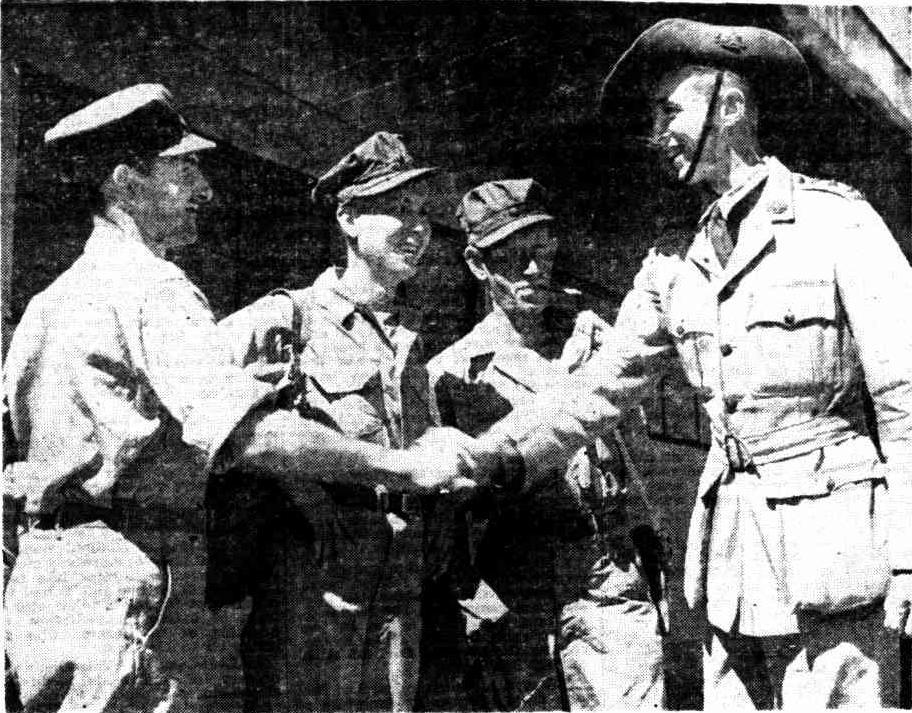

In September 1944, as a prisoner on his way to Japan aboard the Rakuyo Maru, an American submarine—unaware that 1,300 Allied prisoners were onboard—fired a torpedo, sinking the Japanese prison ship. Treading water for 24 hours, Wal and a handful of mates survived being strafed by Japanese aircraft, only to be picked up by another Japanese ship which took them to Japan. Only 159 Allied prisoners were pulled from the water alive. Wal survived barbaric hard labour in Japan and the Allied firebombing of Tokyo and Yokohama, and finally returned to Australia at the end of October 1945. Following the war, Wal travelled to Papua New Guinea to work on boats, and upon his return to Sydney he met his late wife, Helen. Wal became an auctioneer. He and Helen raised their son on the northern beaches of Sydney, after Wal opened a second‑hand furniture shop at Narrabeen.

Wal was heavily involved in the RSL, being recognised for his work with a Medal of the Order of Australia in 2021. He was passionate about raising awareness of the little‑known history of the thousands of Australian and Allied prisoners of war, nurses and civilians who were lost at sea aboard Japanese ships as the result of Allied action. This included the Montevideo Maru, which was sunk 80 years ago next month with the loss of all 1,054 Allied prisoners and civilians aboard.

Wal worked tirelessly to have the memory of those Allied service personnel and civilians who died on Japanese prisoner of war [POW] ships recognised with a memorial on Robert Dunn Reserve at the south end of Mona Vale Headland. But, in an act of bureaucratic bastardry, the New South Wales Government at the time and the local council denied permission for the erection of the memorial. Therefore, it was incredibly hurtful and, quite simply, outrageous when a memorial to the Japanese submariners entombed in their vessel off Bungan Beach was erected on North Mona Vale Headland. We now have an opportunity to right this wrong.

One of the last things Wal learned about was the decision of the council. I am so pleased that veterans Minister David Elliott has given significant funding, together with council, to ensure that Wal's memorial can finally be built, in the location originally intended, on the south end of Mona Vale Headland. One of the very last things that Wal did was to approve the wording for the memorial. It is interesting that it is positioned on the southern headland at Mona Vale, because it is an unwitting but poignant reconciliation of the tragedy of war—Japanese invaders remembered at one headland, allied POWs remembered at the other, all linked by the new coastal walkway along a beachfront which was covered in barbed wire during the war and in front of a golf course built by survivors of the Great War, including my grandfather, Keith Stokes.

Wal is survived by his son Neil, grandsons Robert and Nicholas, and a great‑granddaughter, Sophia. I feel connected to Wal because his story is shared by families like mine and so many others across Australia.

Thank you, Wal, for your service and your incredible life. Lest we forget.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

In NSW Parliament, June 7, 2022 - by The Hon Rob Stokes, MP for Pittwater—Minister for Infrastructure, Minister for Cities, and Minister for Active Transport

It is with a heavy heart that I acknowledge the life and legacy of Wal Williams, OAM. He was a World War II veteran who passed away on Saturday at the RSL ANZAC Village in Narrabeen at the age of 99. A local legend in Pittwater, Wal made a valuable contribution to raising awareness of the sacrifice and suffering of prisoners of war during the Second World War in the Pacific between 1941 and 1945. Born in Northbridge in 1922, Wal grew to be an excellent swimmer and represented the Northbridge Swimming Club at the NSW State Championships. This skill would later help save his life.

Not long after war broke out, Wal enlisted in the permanent army and then joined the Second Australian Imperial Force in November 1941. Wal was underage and needed permission to join up. His father, a Gallipoli veteran of the Light Horse, did not want Wal to be a soldier but eventually gave his permission.

In December 1941, following the Japanese attacks on Pearl Harbor and Malaya, Wal's unit sailed to Singapore to reinforce the 2/19th Battalion, which had suffered casualties just north of Singapore. In one of the strange quirks of history, the 2/19th was commanded by one of my ancestors, Lieutenant Colonel Charles Anderson. Together with his unit, Wal fought a fierce defensive battle for several days. Coinciding with heavy attacks elsewhere on the island's perimeter and on its water supply, and with supplies and ammunition dwindling, the difficult decision was made to surrender Singapore on 15 February 1942. Wal, along with tens of thousands of Allied soldiers, nurses and civilians, was taken prisoner. He would go on to spend three and a half years as a prisoner of the Japanese. At first interned at the infamous Changi prison camp, Wal was then put to work on the Burma‑Thailand Railway—with my uncle, Hugh Johnson—for two years, and would later be transported to Japan.

In September 1944, as a prisoner on his way to Japan aboard the Rakuyo Maru, an American submarine—unaware that 1,300 Allied prisoners were onboard—fired a torpedo, sinking the Japanese prison ship. Treading water for 24 hours, Wal and a handful of mates survived being strafed by Japanese aircraft, only to be picked up by another Japanese ship which took them to Japan. Only 159 Allied prisoners were pulled from the water alive. Wal survived barbaric hard labour in Japan and the Allied firebombing of Tokyo and Yokohama, and finally returned to Australia at the end of October 1945. Following the war, Wal travelled to Papua New Guinea to work on boats, and upon his return to Sydney he met his late wife, Helen. Wal became an auctioneer. He and Helen raised their son on the northern beaches of Sydney, after Wal opened a second‑hand furniture shop at Narrabeen.

Wal was heavily involved in the RSL, being recognised for his work with a Medal of the Order of Australia in 2021. He was passionate about raising awareness of the little‑known history of the thousands of Australian and Allied prisoners of war, nurses and civilians who were lost at sea aboard Japanese ships as the result of Allied action. This included the Montevideo Maru, which was sunk 80 years ago next month with the loss of all 1,054 Allied prisoners and civilians aboard.

Wal worked tirelessly to have the memory of those Allied service personnel and civilians who died on Japanese prisoner of war [POW] ships recognised with a memorial on Robert Dunn Reserve at the south end of Mona Vale Headland. But, in an act of bureaucratic bastardry, the New South Wales Government at the time and the local council denied permission for the erection of the memorial. Therefore, it was incredibly hurtful and, quite simply, outrageous when a memorial to the Japanese submariners entombed in their vessel off Bungan Beach was erected on North Mona Vale Headland. We now have an opportunity to right this wrong.

One of the last things Wal learned about was the decision of the council. I am so pleased that veterans Minister David Elliott has given significant funding, together with council, to ensure that Wal's memorial can finally be built, in the location originally intended, on the south end of Mona Vale Headland. One of the very last things that Wal did was to approve the wording for the memorial. It is interesting that it is positioned on the southern headland at Mona Vale, because it is an unwitting but poignant reconciliation of the tragedy of war—Japanese invaders remembered at one headland, allied POWs remembered at the other, all linked by the new coastal walkway along a beachfront which was covered in barbed wire during the war and in front of a golf course built by survivors of the Great War, including my grandfather, Keith Stokes.

Wal is survived by his son Neil, grandsons Robert and Nicholas, and a great‑granddaughter, Sophia. I feel connected to Wal because his story is shared by families like mine and so many others across Australia.

Thank you, Wal, for your service and your incredible life.

Lest we forget.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

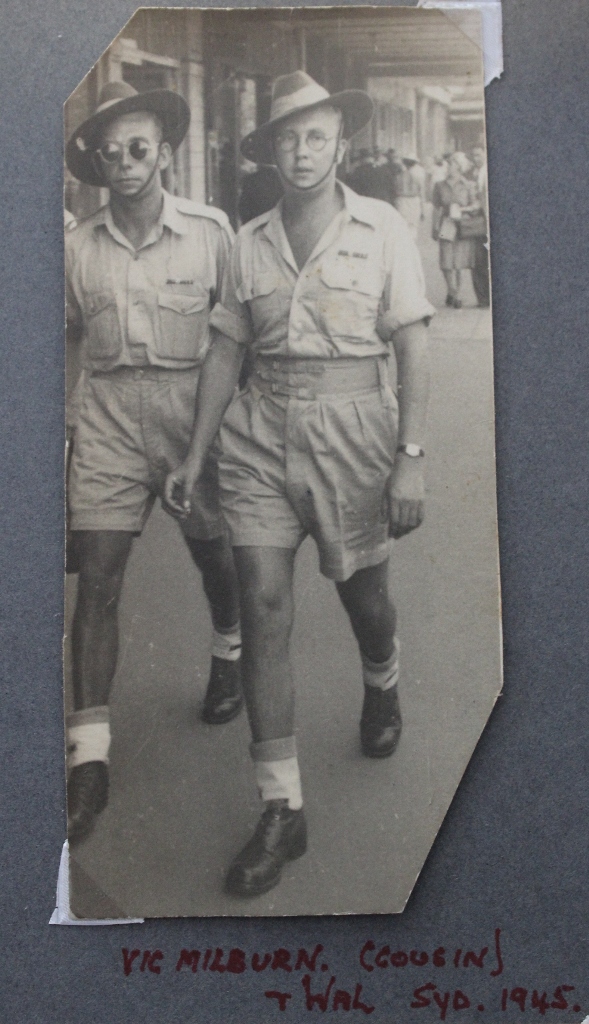

2017 Profile

Wal Williams is a legend in Pittwater, a World War II Veteran, Mr. Williams has worked tirelessly for decades when Pittwater RSL Sub-Branch President to look after members and was present, along with fellow WWI Veteran Brian Sargeson at the May 16, 1999 dedication and Official opening of the original Cenotaph at Pittwater RSL.

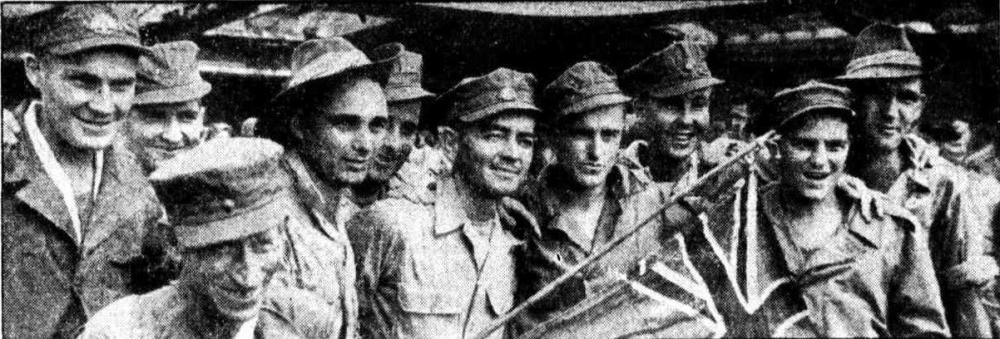

Taken prisoner at the fall of Singapore, Wal worked on the Burma Railway prior to being sent to Japan to work, and experienced being sunk en-route. He survived Changi, he survived Burma, he survived being in the open ocean prior to being picked up again and sent to Japan for a year of hard work and being the focus of anger when the bombing of Japan began. He survived the firebombing of Tokyo and Yokohama by Allied bombers and finally returned home on October 10th, 1945 - his 23rd birthday.

When we asked him how he kept his spirits up he referred us back to the jokes by a 'voice that would sing out' with something at times when he and those he fought or survived beside were in direst straits - small witticisms he still laughs at in recalling.

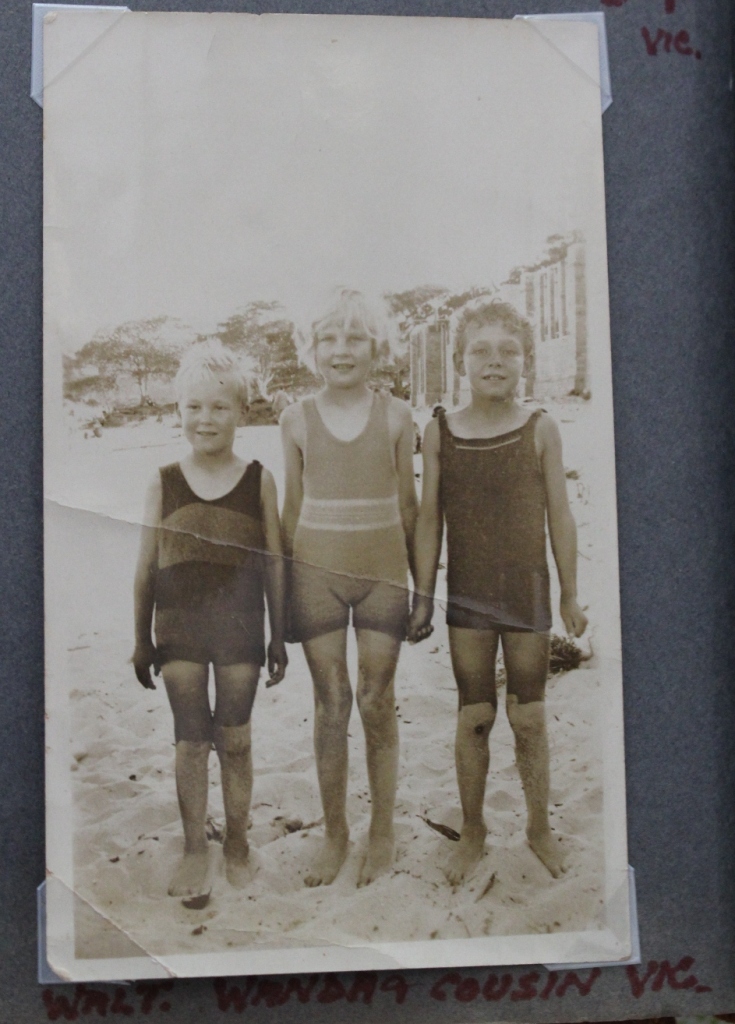

Where and when were you were born and what did you do while growing up?I was born on 10th of October 1922. My parents were Frank Gordon Williams and my mother, Letita Maie Williams.

I was brought up at 45 Cliff Avenue, Northbridge.

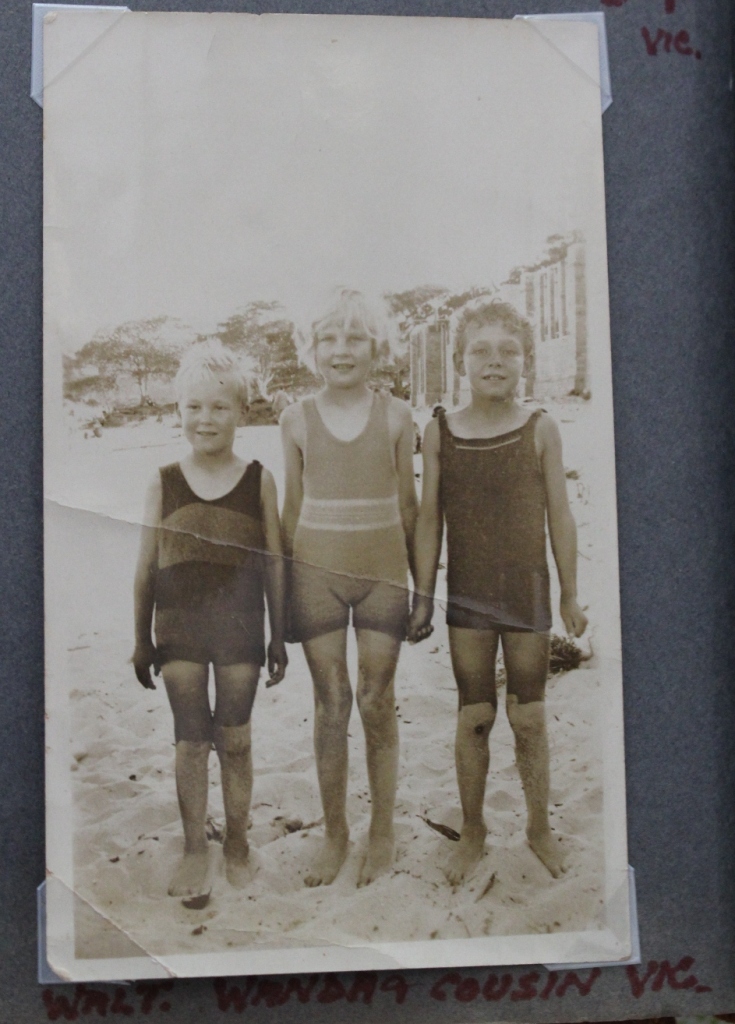

As a young fella I was a good swimmer, it was the thing of the day then. My father was a good swimmer too, before I came along. I joined the Northbridge swimming club when I was a kid; probably before I was ten, but I competed in competitive swimming from ten years of age up until the war. I won numerous championships there, point scores, and I represented at about 12 years of age in the New South Wales State Championships. I swam in the Old Domain Baths which no longer exist. They were tidal baths in those days, in the Domain in the Harbour.

General view of the Baths (Domain Baths, Woolloomooloo, c.1930s, by Sam Hood, courtesy State Library of NSW

What was Northbridge like when you were a child?Northbridge was like a village in those days. Most people knew all the families that were there. There were vast amounts of bush. My recollection of Northbridge at the Point, which overlooks the Spit now, is that there was only one residence there which was owned by Hallstrom who was the patron of the Taronga Park Zoo. He had a factory in Willoughby which produced the Silent Night refrigerators. Prior to that we didn't have refrigerators, we just had ice chests. He was about the first fella that produced them. He produced electric, gas and kerosene fridges from that factory in Willoughby.

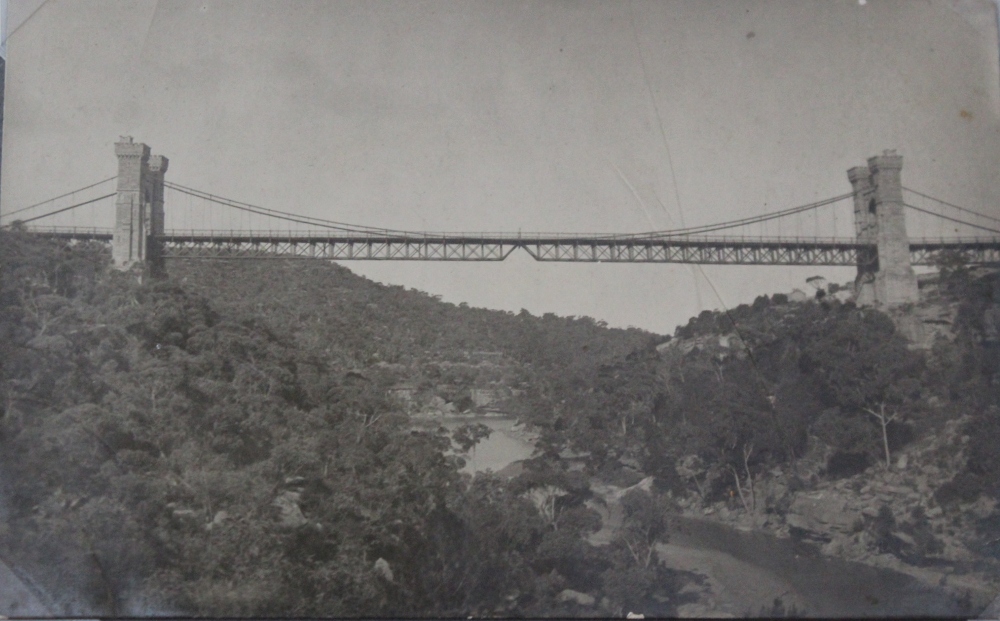

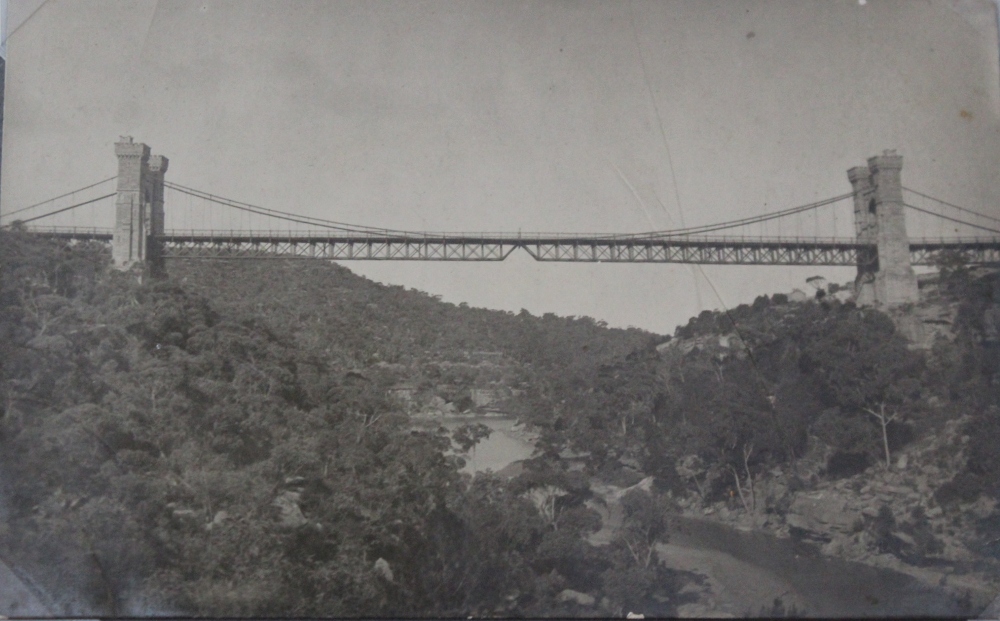

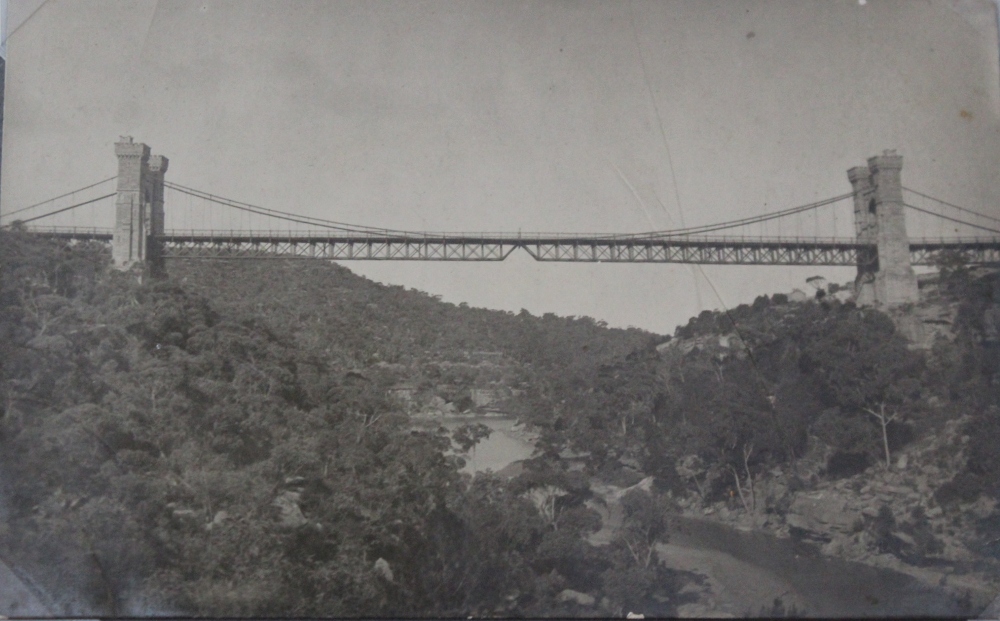

I’ll tell you a funny story about my Billycart at Northbridge. See this photo here, that’s the old suspension bridge at Northbridge in nineteen hundred and twelve (1912). I have a photo here of the old suspension bridge in my album.

We lived right opposite the bridge. This shows the road going over the bridge to Cammeray. I lived on the first street on the right, my father went out there after the First World war and had one of the first homes that was built there. You can see that tram, that later went over the bridge up to Northbridge.

We used to have to go from the end of that bridge, where we lived, up to the shops. Mother used to give us a list and sister and I used to go up and buy all the stuff. I used to come down Strathallen avenue, which is the main street down towards the bridge in the billycart. I’d be driving and my sister would have her back up against me. We used to come off the bitumen road into Marana road, which was a dirt road in those days. I swung the billycart round, into the dirt, and all of a sudden I started getting wet on my backside. I thought, ‘oh no, don’t tell me Wanda’s wet herself’.

I had a brake on the billycart so I pulled that and said, ‘are you alright?’ – ‘yeah’ – it was the bloody eggs, they’d broken. So I pull up, and of course everybody knew everybody, so I ran into Mrs. So and so’s place and got a basin. There were three or four that weren’t broken but the rest, ‘there you are mum, there’s the eggs, we’ve still got a dozen.’

The trams used to run then and would run down to Northbridge school, that’s where they terminated. So of course as kids we used to scale the trams to get home, it was a great place for a kid then.

Where did you go to school?My primary education was at Northbridge Public School which was to sixth grade, and from there I went to Crows Nest Commercial School which was on Pacific Highway, I think it's still there. I educated up to Intermediate standard and then left school, as did 90% of the boys then, they left school and went to work. Those that had brains went to North Sydney Boys High School, did an extra two years and sat for the Leaving Certificate.

Whilst I was in high school my mother died at a young age which upset me a lot. My father got married again and he had one son, my half brother.

What did you want to do when you left school?

Good question. When I left school I would only have been in those days about sixteen, I did signwriting and went to Tech in a factory in North Sydney, in Mount Street North Sydney which was called Standard Signs. They did silk screen processes and spray painting and that kind of thing.

The war broke out in the September of 1939. I enlisted in the Permanent Army on 13 January 1940 when I was 17, and then joined the AIF21 November 1941, which I’d wanted to do but which my father was against this, he having served in Gallipoli, in the 12th Light Horse, where he was wounded. He was dead crooked on me going into the Army. To be quite honest, he wouldn't give me permission.

I was under age, so I had to get a signed document from him giving me permission, which he wouldn’t do initially but he did get me into the Permanent Army. I was posted on the staff at the Royal Military College at Duntroon. Then my father, although he was a Gallipoli veteran, joined up in the Second World War and was stationed at Victoria Barracks as a Warrant Officer. I came down to Sydney on Leave and said to him I still wanted to get into the AIF, it was very hard to transfer from the Permanent Army into the AIF [Australian Imperial Force].

The AIF wasn't far from there, at the showgrounds where they were recruiting. He finally gave me permission. I went in there and we were sent to the 8th Infantry Battalion at Dubbo and we did our training at Dubbo.

We left Dubbo in December 1941 and we sailed on the Aquatania from Sydney Harbour to Singapore. We arrived in Singapore in December 1941. Of course at that time the war had started on the 8th December which corresponded with the attack on Pearl Harbour and the attack on Malaya. Our unit had a big battle at Muar and they had lost a fair amount of blokes. They had lost about two or three hundred blokes I think, probably more. We came in as reinforcements into the 2/19th Battalion from the base depot camp in Malaya.

The Australians had the territory of Johore Bahru, that was the most southern state in Malaya. That was their defence perimeter. We went into this outer bridgehead and what troops were left in Malaya then withdrew through us across the Causeway which links Malaya to Singapore Island.

We went across and we were followed by the Argyle and Southern Highlanders and they piped us across. Why the hell the Japanese never attacked at that time I'll never know. Prior to that there had been plenty of air activity because we had no real planes and we had had just about had it. They were obsolete aircraft in comparison to the Japanese Zero.

Luckily for us and all the troops going back to Singapore Island, they never attacked us, because if they had; the causeway is a only narrow roadway which goes from Malaya to Singapore. It's got a railway line on it and a roadway and a main pipeline, a water pipe line.

When we got to Singapore, of course we had all been led to believe that Singapore was an impregnable fortress and everything else you see. Well, we got onto Singapore Island and they blew the causeway, blew a certain section out of it. I don't know, quite a decent section and we thought 'Oh well, everything will be right, you know. We've got defences here'.

Of course the English troops had been there for years. We got allocated this position and we went out to the North West part of Singapore Island at Kranji, and when we got out there, there was nothing. It was just like virgin bush. It was just like out here at West Head. It was only about half a mile wide strait between Malaya and Singapore, no more than West Head to Palm Beach. Of course when we went there, it was just virgin shrub and a secondary rubber plantation. I was in B Company, the 2/19th Battalion, 7th Platoon and we were stuck down on the coconut grove which was down at the water's edge. It was the only bit of flat ground around, and it was the logical place where the Japs would land. We all knew it and probably the Nips did too.

Where we were the water table was that low, you couldn't dig slit trenches. You could only go down probably a foot and you'd hit water.We dug these sort of depressions in the ground which enabled us to lay in them because we were then a bit below the ground level. Further back from where we were they did have slit trenches but we couldn't near the water.

Primarily we were with these Very Pistols (Flare guns) and when we estimated that the Japs were going to come over and land on Singapore Island, when they were half way across the strait, we were to fire these Very Pistols and then the artillery which was up in the hills behind us was to open up.

At that time came when our CO [Commanding Officer] who was Colonel Anderson, he got the VC [Victoria Cross] there, was back at Battalion Headquarters. He got crook. He got dysentery bad. It got to the stage, that day, it was the 8th February, he was taken to hospital. He was replaced by Major Robinson out of the 2/26th Battalion. And of course, the artillery and the mortar fire was that bad there that he decided to shift Battalion Headquarters at that late stage. It was a fatal mistake.

He shifted it and it was off the high ground. They were copping a pasting and so were we.

The actual bombardment, and the aircraft were pretty bad too; machine gunning and bombing and what have you. We were under a terrific barrage of artillery and what have you and we just lay there for most of the afternoon. It was about half past eight at night when they came over.

Prior to the Jap landing, we sent a Lieutenant and a Sergeant Donnelly and Dempsey and they went across back to Malaya in a canoe because they had trained in that area and they mapped it all.; where they were, where their artillery was and their mortars and everything else. Then they came back through out section.

That was a bit after midnight on the 8th prior to the Nips landing. The landing was on the 8th. Of course, they came back and they said, 'We'll give these blokes some hurry up' and of course I was there when they came back and they went back to Company Headquarters then Battalion Headquarters. They went back to Divisional Headquarters and told them what had gone on, and we assumed that everything would be right.

When the Japs did land, we fired these Very Pistols and could see there were about fifty boatloads of them coming across. We opened up with what we had. We only had rifles and in our section we had a Lewis gun and a Bren gun, and of course we opened up on them and we were just overwhelmed. There were just too many of them.

About a quarter of the Battalion had been wounded prior to this through shellfire and mortar fire. A lot of them had been evacuated to hospitals in Singapore. I suppose there must have been about eight of us in our section then. Behind us was the rest of the platoon and Lieutenant Bataris, he was the platoon commander then. We got pushed back off there back to Company Headquarters and of course this was all at night. Bataris was killed. He got killed between Company Headquarters and Battalion Headquarters.

With Robinson moving the Battalion Headquarters, a lot of blokes didn't know where it had gone. They knew where the original position was, so a lot of blokes just wandered back to where they thought it was but it wasn't there. I remember a bloke asking me and I said ‘I don't know where it is. They've shifted it and I wouldn't have a clue.’

So we got there and of course the Japanese had the high ground. They got the high ground that we had and it was only through, Sergeant Parry Moore and some other bloke, can't think of his name, that we didn't get killed then and there. They put up a hell of a fight, because they had Bren guns and they got stuck into the Nips. We were surrounded. We couldn't get out. We had all the wounded in the various vehicles and what have you. The Japs would come around the back and put road blocks on the road. There was no way that the transports could get out.

So, there was a swamp up the back of where we were, and these blokes with the Bren carriers held up the Nips and we got out through the swamp. This was no mean feat. It was water up to your neck and all the mangroves and mud and God knows what. Anyway, we got out of there.

What fellas came out of there were taken back to Tangelong aerodrome and we formed up. We struck an Indian Brigade there and they transported us back to the General Base Depot. From there they reformed what they called an X Battalion.

It was all the odds and sods because things were pretty disorganised. The artillery never fired. No artillery fire came across. So it defeated our purpose. All that work that Otley and the others did going over there was for naught. We couldn't understand it. Why the hell didn't the artillery fire because it was impossible for them not to see the Very pistols.

Enquiries were made after the capitulation, when we were back in Selerang Barracks. They went and saw these artillery commanders and said, ‘Why the hell didn't you fire?’, and they said they were never notified by Divisional Headquarters. So whether that's true I don't know, but it seemed funny to me that the artillery. I mean, you'd think they would have taken that on themselves and opened up, but they didn't. That was a fatal mistake because we had no hope after that.

This X Battalion they formed, we went up in a pitch black night, you couldn't see your hand in front of you; we had to hold on to the bayonet of the bloke in front of you. If you walked off the road you wouldn't know where you were.

We got into this position, the intelligence guy found the mile pegs which told us where we were. How he found it I'll never know, but he did. But as it turned out I wish to God he hadn't found it. We went in and I think we must have walked right into the Japs. They must have heard us. They just let us settle down. That was about three o'clock in the morning. And of course everyone was pretty tired. We just worked it out, to have an hour's kip before daylight. Anyhow, the next thing we knew the place was lit up like daylight. Right in front of where we were there was a great stack of 44 gallon drums full of fuel. There were a couple of tanks there that the Japs had mortared and set fire to which enabled us to be lit up like daylight. Of course, they got stuck in and there weren’t many blokes who got out of that. All the officers were killed. They must have been having a meeting or something at their headquarters and they got the lot of them.

Our Company commander was a bloke called Keegan, Captain Keegan, and he came out. He was badly wounded. When this was lit up, my first impression was I could see all these blokes running up this hill and they were chopping them up. Something said to me, ‘Don't go up there, go around’, and I did. I veered off and I went around a bit of a hill.

I was on my own. I got in this jungle and I could hear all these blokes crashing around. You wouldn't know if they were Nips or who they were. I heard this bloke, I don't know if he had barked his shin or what but he said ‘Bugger it’ or something like that so I knew he was Australian. I recognised the bloke's voice. He was a sergeant by the name of Bernie Weaver and he was in our platoon.

I sang out to him and told him who I was and he said, ‘Come in'. So we came out on a compass bearing. He was badly wounded and we couldn't get him out. We had to leave him. It was a bloody terrible thing.He just said, ‘Leave me. It's impossible'. We couldn't carry him out.

Anyway, we came out on a compass bearing. It was pitch black dark and we all got round in a huddle and some bloke lit a cigarette lighter so we could take a bearing off this compass which we did. And we came out on that.

We were only challenged once and that was by some Malayan troops who had an armoured car, and they were a bit off the main road at the time. We came out through them and got on this main road and all the oil tanks had been set alight. It was lit up like daylight. There was a lot of black smoke and we all got covered in that. We walked all the way back into Singapore itself. We never got challenged once.

We said to ourselves, ‘If we can walk down this road, what can stop the Japs?’

When we got back into Singapore, there was this Pommie officer with a girl on his arm and he was saying to us, looking us up and down covered with black from the smoke, ‘You're a bloody disgrace to your uniform’, and we had only just come out of this action and we weren't too happy. So we told him what we thought of him.

I thought he was a bloody idiot. See, the Pommies never realised the seriousness of the situation. They were carrying on saying the Japs will never take this island but it was already gone. It was gone by the time we got back on Singapore Island. We had no hope of defending it. We had five miles or something to defend. It was an impossibility, you just couldn't do it. We never had the manpower.

We went back to the Base Depot. They sent a message out for all the blokes in the Battalion to join them in the Botanical Gardens.And that was the last position we took up. The Botanical Gardens in Singapore.

Whilst there, I went out on a patrol. The last patrol I did with this bloke Weaver. Anderson told us to go out and follow the railway line down a thousand yards, and he said, ‘You're not a fighting patrol, I want to know what's going on - do some reconnaissance’.

So when we got out there we struck a couple of Indian blokes and they had no arms on them. We said, ‘Were their any Japs in the vicinity?’, everybody knew what a Nip is or a Jap. It didn't matter what lingo they spoke. They said, ‘No there's none around Here’.

I'm pretty sure we took these two guys with us. We climbed up this railway embankment and got on to the railway line and we could see these blokes a fair way off, and they had on a pith helmet. I'd never seen a Jap with a pith helmet on, I thought they were Pommies first so we sang out to these jokers. They stopped and I saw a bloke get down behind an automatic weapon and I looked over the railway embankment and there were a lot of Nips coming on to the railway line, and they were walking down to Singapore, following the railway line.

So we knew they were Nips and we beat it. We came back to the Botanical Gardens and we stayed there until the next day when they signed the capitulation.

That night, the officers must have received word, or Anderson must have received word and he probably told the officers. They said to us that ‘There will be no more shooting. You have to hand your weapons in’.

Everybody was dumbfounded. We felt terribly let down and depressed. We had a sense of guilt. It was a bloody rotten feeling I don't might telling you because we were prepared, we thought we could still have a go.

The next day our rifles were taken and stacked.

We received orders to march out to Changi. That was a terrible march. A stop-start thing because there were thousands of blokes. You couldn't work it out. You'd only go a few hundred yards and then stop. But when you got to the end of it, they were giving blokes a bit of a feed, and that was the reason. Everybody had stopped right down like a chain reaction.

We all went out to Selerang Barracks which was originally the station of the Gordon Highlands because they had been there before the war. These were substantial buildings and they just crammed thousands and thousands into them. We were just sleeping on the concrete floors.

I left Changi on a working party to go back into Singapore. We worked on the wharves there loading ships and checking out stuff in these warehouses or go-downs as they called them.

This reminds me of my first introduction to my captors. I went into Singapore to work and we were going into this camp that was like Luna Park, and was in, I think, River Valley Road – I used to go down there before. They told us this is where we were staying. There were all these exhibits and you had to do the best you could regarding where you were going to sleep.

Just before we went into this place I looked up and there were these two Chinese blokes they’d beheaded and they’d stuck them on posts; I thought to myself ‘God, what are we in for?’

That also reminds me of when we first went into Singapore – I was with one of my mates and we went into these warehouses – you should have seen the stuff they had in there, we could have lived there for years there was so much stuff. The Chinese were good to us, they looked after us, but the Japanese, goodness, they knocked them off, so many of them were killed, hundreds of thousands of them around us.

At any rate, they wanted sewing needles, Singer sewing needles and parts. We’d get into these joints and knock them off for them. I’ve always remembered how we’d build these tunnels out of boxes into and through these places and you could go into these warehouses and knock off some tins of food and have a decent feed and the Japs wouldn’t know. We were living better then than we ever were in the Army.

The time came when the Japs must have taken an inventory of what was in the joint.They lined us up and the officer came out and said, through a translator, ‘we know that you’ve been pinching this stuff. Now, we’re giving you the opportunity to put it over there’, indicating a loading dock where the trucks used to come in in the old days, ‘and after that we’re going to search you. Anyone found with something will cop it.’I had the brains to know to put whatever I had there.

When they formed us up in a line outside again I glanced over there and it was like looking into the back of the Macarars grocery store there was that much stuff. Macarars in those days was a big grocery joint. Something like Woolworths today.

The guard was then coming down the line, frisking every bloke. There was a little bloke alongside me, don’t know who he was, who said to me, ‘what I’m I going to do? I’ve got a seven pound tin of bully beef’.I never knew they even made a seven pound tin of bully beef!

I said, ‘put it on the ground and stand on it’ – which is what he did, and he still only came up to here’ (indicating shoulder)Luckily for him the guard coming down was swinging his arms about and hit this bloke’s A.I.F. hat just a few men down and all these Tally-ho cigarette papers went flying everywhere – they were like confetti.

The Jap went off his brain, he went red in the face and belted this bloke. When he came back he forgot where he was up to and missed this kid and came to me. I had nothing on me, and he got away.

We had to get cunning though – the medical water bottles, which were a lot larger than the regular water bottles, were doctored. The blokes would take all the felt off and the webbing and cut it so they could put a false bottom in it. This they’d fill up with sugar or tea or something else and then shove that back so the other part still had water in it. (starts Laughing)I’ll never forget this bloody day – one of these blokes had one of these water bottles and the silly bugger had filled it up with Worcerstshire sauce. It was a stinking hot day and one of the Japs said to him ‘Aqua! Aqua!’ and took his bloody bottle and went woof woof, drinking it, and then almost choked. He went right off. You can imagine this bloke – he took of like a Bondi tram!

I got crook then with Dengue fever and was sent back to Changi. When I got better in April 1942, they formed this 'A Force' they called it. It had about three thousand men and told us a cock and bull story that we were going to a rest camp and the food would be good and we needn't take implements or anything. That everything would be provided.

At that stage you took them on trust. It didn't take us long to wake up though because news filtered back. There's always someone who comes from somewhere and tells you what's going on. We went back in then, we left I think in late April 1942, and went by truck back into Changi into Singapore wharves.

We were put on a ship called the Celebes Maru. I was shoved down this hole and it was terrible. On top of that of course a lot of blokes had dysentery and fouled themselves. The stench was rotten. It was terrible.

It was about a nine day trip. We left Singapore. We went across to Sumatra and picked up some soldiers. We went into southern Burma then. We were dropped off at a place called Mag-u-e. There was one drop before us and that was at Victoria Point. Some blokes went to Tav-voy which was about 150 miles up the coast.

We were billeted in the local school which was overcrowded and pretty crook. We were sleeping on concrete floors. Then we worked on an aerodrome there. I think it had probably been bombed. We filled the holes in. We had to knap stone, which is with a little hammer and a block and bash it up into the size of blue metal and blokes would carry it out on bags strung between bamboo poles. Then they would tip it out and spread it to resurface this aerodrome.

This wasn't too bad there, if we had known what was ahead of us. In comparison it wasn't bad.Conditions were crowded in this school and the officers put pressure on the Japs. The actual Nip who was in charge wasn't a bad sort of a bloke. He was a bit our way I think. Eventually there was a camp that had been built for the Japs. It was only built out of bamboo and palm leaves. They put them on the roofs and they set it up just like tiles. The water just ran off. This camp had been built for the Nips who were going to garrison this town, but they must have changed their program as they moved us into it. To cut a long story short, it wasn't a bad sort of a camp.This was also the place of our first experience of executions; while there when a couple of blokes escaped or attempted to escape. There was no trial or anything, they got shot.

While we were there the officer was Lieutenant Colonel Ramsey from the 2/18th Battalion and that force became known as Ramsey force. I can't remember how many were in Ramsey force. I reckon a thousand blokes. It was split up.

We were there for about three months I reckon, and then we moved up to Tavoy, 150 mile up the coast. We worked on the same sort of set up. Cleaning up around the place. Billeted in the local school again. That wasn't too good as the hygiene system was crook. There were no toilet facilities. We had to dig toilets. Blokes were starting to get crook then and get dysentery and those sort of things. It was just bloody disgraceful.They would just overflow and some blokes were that crook they would have to sleep near them because they just wouldn't make it from the hut to the latrines.

When we finished working in Tavoy, which was roughly another three months I reckon, we went to a place called Ye which is a rail head, in South Burma, and from there we walked for about 40 kilometres or something. It might have been 20-30 kilometres. We had to cross this river and of course the bridge had been blown by the British when they withdrew out of Burma back into India, so we had to go across this river in canoes.

We walked to Tameside and went past all these salt marshes, where they make salt with water then drain it off, and of course everybody was dying for salt. Everyone wanted to fill up their billy cans or whatever cans they had. They wouldn't allow it, but some blokes got it. We were only getting to eat just rice around twice a day then, and not much else.

We finally arrived at this joint called Thanbyuzayat, and that was the big base camp and railway marshalling yards for the rail line that went up to Merlbeen and up into Rangoon, up into Burma. That’s where they started the line from there out through Burma to the border which was what they called the Three Pagoda Pass.

When we got there we all assembled and this Jap came out, a Lieutenant Colonel Nagatomo I think his name was. He addressed us and he just said, ‘You're a heap of rabble and garbage and you're under the Nips. The Emperor spared you and all this garbage’. And he said, I'll always remember, he said ‘This railway will go through and be built even if it's over your dead bodies’.

Of course at that time we looked and you could see all the mountains and we said, ‘There's no way we could put a railway through here’. But he was right. He put it through over our dead bodies all right!

We went out to the camps on the Burma side, which were always referred to by the kilometre. The first camp we were in we called it the 26th Kilo. Well we didn't know what a kilo was in those days, or a kilometre because it was all miles in our day. So all these camps were called that, and we went to 26 Kilo camp and that would be short for kilometre camp. Whilst we were at the 26 Kilo we were working on the railway clearing for the rail. It was fairly flat country there, and they had special gangs then which came behind and did ballasting of the line; laid rails; the rails and sleepers were laid and dog spiked.

I remember whilst we were there we conned the Japs into thinking it was Melbourne Cup so that must have been in November 1942, and that this was a National holiday and they gave us half a day off.

They put on a Melbourne Cup race, with hobby horses. We didn't have the wheels but they made a sort of a head, and these blokes ran heats and everything else, and then it got down to the final. They had bookmakers and all the business, just like the races. They made this sort of thing like a tote out of bamboo. They took all the names of the horses of previous winners of the Melbourne Cup; Windbag and all these names.

I don't know what they thought of it. They got into the swim, into the mood of it all. They must have seen what was going on, these foot races. The Colonel arrived in the bullock cart; he was supposed to be the Governor General. He put on all the act. Anyway, it was a day off, that's all we were interested in.

We lived in huts made out of bamboo with a deck of bamboo. Raised up off the ground, the mud. You'd get all these blokes tramping into camp and in the middle of the hut which had one central passage way down, and each side had raised platforms, and you slept on that. Some of them were two tier huts and blokes would sleep on the top tier, but most of them, from my memory, were on the one deck. They were pretty uncomfortable because you didn't have a mattress or straw. Sometimes you might have a couple of chaff bags or something like that that you had scrounged somewhere and you'd hang on to them like grim death.

It was hard to sleep. All the knots in the bamboo would just get into your flesh. This part down here on your hip would just look like it was bruised through sleeping on it. You never had much space of course.

Of a morning you'd have a pannikin full of gluggy tasteless rice and then they'd line you up. They would count you, they would take hours to count the blokes. They'd go down, and down and go down and away we'd go.

If you can visualise where we started, the line, you might go three kilometres that way and three kilometres that way, then you'd join with another mob from another camp and they would be coming three kilometres this way and you'd join up. Then when you did that area you'd move again, and you'd move the camp. At the 26 Kilo camp I think we did embankment work.

You'd get up on top of a fairly large mountain, a big hill. And you'd virtually start from the top and you'd cut all the bush and everything else a certain width and then you'd start digging. You might go down forty or fifty feet. You'd start with a big wide area at the top of the mountain come down, you'd slope it down like - they call battering it. If you went straight down the whole thing would fall in. So we would start at the top with a good width, and then as you dig you would come right down to where the track was. A track would be wide enough for the train and a bit on either side. This bank would come right down, and all the earth would go to the end of the cutting and be tipped into the valley. Like both ends of the cutting.

We never had wheel barrows as we know them now. We had 44 gallon drums cut in half sort of a structure. Most of it was done in carrying baskets, wicker baskets.

When it was dipped into the end of the cutting, you'd have to build a bridge across that gully to the other mountain. Blokes on the other side would be doing the same, or if there was a gully you'd have to put a bridge across it. When we did that we would have to drive piles into the ground. First the timber would have to go and be cut, cut out of the jungle. It would take at least three blokes to carry a pile. They had elephants working there too. The elephant would get hold of it and he would just get the weight, the balance of the thing and he'd carry the damn thing down and drop it.

Of course the poor elephants were under stress. I remember there at one stage, this poor elephant – I suppose it was starving like we were. Anyway, it just turned up its toes and died. Bloody great thing, it just fell on the ground. The Nips came along and said, ‘Bury the elephant’. If you've ever seen an elephant lying on its side, it's like a bloody mountain.

We said, ‘If we dig a hole how are we going to get it in the hole!’ You'd never shift it. You'd want a bulldozer or something. So they left it and the stink, Christ! But the vultures cleaned it up and after a couple of weeks there was nothing left of it.

We had to pass it every day going to work. Everybody would hold their nose and run. It was rotten.

The weather then was hot and dry. That was prior to the wet season.

When the wet season started we left the 26 Kilo camp and went to the 75. The 75 Kilo camp wasn't too bad. It had a river right near the camp.When we finished work we could just go into the river and have a bit of a wash. Cool off.

While we were there at the 75th more urgency was put on us, they told us the line had to be finished, I think it was in September 1943.This soon translated into us working all day and night. There were two shifts. At night they used to have big bamboo fires and they would have blokes just chucking on bamboo.

That was their job. The others were working by this fire light which was hopeless if you were doing dangerous work like bridge work. There were a lot of accidents.Blokes would fall off scaffolding especially in the bridge work; you could fall off the scaffold or something like that. It was pretty dangerous.

That's where we did a bit of bridge work at the 75 Kilo. They would have a big bamboo structure built, like a dolly or monkey they called it. It would either be out of steel or a big lump of teak wood. They'd pull it up. They would have a heap of blokes. There might be 20-30 blokes pulling this thing up and it would be positioned over the pile and just let her go. It would just go down and it might drive it about that much. Back you'd go again.

They would drive in about 20-25 of these things a day. That was a shift. It was hard work. The rations were crook and of course when the wet season came, it rained.

I never saw rain like it in my life. It rained 72 hours non-stop and it was that heavy. Of course we had no clothing. All the clothing we had like shorts had rotted away. We made lap lap things. We styled them on what the Japs used. It's like their underpants.

It's made of calico. Just two pieces of material with tape on it and they tie it around their waist. Put it down, pull it up through your crutch and drop it down over the top of thing. That's all we worked in.

Some of these camps we went into, we'd have to clean up. There would be crap everywhere; there would be dead bodies of natives. We would have to clean it all up. One camp we had to skim the whole top of the dirt before we could move in. The only thing that saved us was hygiene. That was a number one priority. All our cooking utensils and eating utensils, they had like half 44 gallon drums and boiling water all the time. We would be stoking up the boiling water. All the water we drank had to be boiled otherwise if you drank it out of the river and creeks and things you would have a chance of getting cholera.

We had our own medical staff. We might have had a couple of blokes from a medical unit, but they took other fellas in and trained them and they would look after the sick. We had huts, sick huts if you were crook.

Of course the Japs demanded so many men every day to go out and work on the railway, but it was just an impossibility to get enough. The Japs would go off their brains. All they wanted was body count. They wouldn't care if they were crook, couldn't work or what have you. So long as they could get 200 men or 300 men or what ever it was to go out every day, then they were happy. And of course when they couldn't get it they would just come into the huts and they would get blokes out who they reckoned were fit enough.They'd line them up and come down the line, and say ‘You you and you. Go.’

When we were up there in the wet season, it was terrible. You were up to your knees in mud. It just turned all the roads, all the so called roads that were all right in the dry weather, but in the wet they couldn't even get trucks through.

We corduroyed, which is cutting saplings and laid them side by side for miles and miles. We had to cut rock first as ballast and then put these timbers over it, then get these lorries over. The Japs were going up into Burma. They were going past our camps all the time. The idea of this railway was to transport their troops and food and stuff like that.

From there we went to the 105 and that was the last camp for the A Force in Burma and that was the worst camp. We had to cart water for about a mile from a creek. That was tough when you've got a fair amount of men in a camp. They drink a fair amount of water especially in the tropics. They had gangs of blokes carting water. Two blokes with water containers. They might have been kerosene tins or anything. They'd be carting it into the camp and tipping it into drums. They would be boiling it all up and if a bloke wanted a drink he'd have to ladle it into a pannikin of water. And all that would have to be taken out to the work force too. Like the food, the midday meal, if it was three meals a day. Sometimes it was only two meals a day, but if you had three meals a day you would have to cart it out, and the water would go with you.

That 105 camp, that was the worst camp. You name it, it had Black Water fever; it had Dengue fever; Cholera broke out there and of course the Japs were very frightened of Cholera. Any blokes who had Cholera they would be in isolation.

I got crook. I had malaria and dysentery and the worst things were tropical ulcers on your leg. You could get them anywhere. You would nick yourself with a bit of bamboo or something. When you were on rockwork any chips of rock that hit your leg, well there was a good chance it would turn into an ulcer.

We had a hell of a lot of sick blokes at that camp. They couldn't really get sufficient blokes to go to work. Not the numbers the Nips wanted. Anyway to cut a long story short, this Jap, the head guy, Nagatomo, he came up and had a look and he was horrified. I think when he saw the condition the blokes were in, not that he had any sympathy, but he said they would open up a hospital camp at the 55 kilo which was back down the line. We had visions of hospitals and all this business but it was just an ordinary camp. It was no better than the one we were in.

When we got down there they had about 500 ulcer cases shoved in these huts. God it was terrible for those blokes. They had to get these ulcers scraped with something like a salt spoon to get all the pus and crap out of them. Blokes used to see them coming down and they would be nervous wrecks before they even treated them.

I got ulcers, but some blokes had them exposed from the knee right down. You could see the bone. Eventually if they got gangrene they would have to amputate their leg. A lot didn't make it.

At this 55 camp I had them on my leg but I would go in these creeks and these little fish would come up and go bang bang and pick all the crap out of it. It used to hurt like buggery, but they would get all the muck out of the wound and you had a chance of healing it up.

Colonel Coates he was the head chief medical officer, and he used to do all these amputations and one thing or another. Some blokes survived it. I had a mate who survived it, but a lot of blokes didn't. They were living on a pretty crook diet. They never had any medicine, anything that we could get from the natives we would give to the sick. Give them a bit of chance. It was a horrible camp.

When Colonel Coates, Chief Medical Officer, arrived in this camp he had Black Water fever. He arrived on a stretcher and for the first two weeks he did all his inspection of the ulcer wards from a stretcher until he recovered. There would have been at least 50 cases of tropical ulcers. Very bad.

One day we were sitting around and Coates said ‘Look, I've got to take this fella's leg off’ ‘I'd like you to come down and have a look at it.’

I went down with other fellas.

He said, ‘I'll explain it to you’. So he took this fella's leg… Coates used to smoke a cigar. We used to be able to buy cigars in Burma cheap and most blokes smoked in those days.

Anyway with these cigars it would take about an hour to smoke one. They were bloody long things and big. Anyhow, while Coates is performing this operation, he never had anaesthetics, as we know them. There was an extract by a Dutch chemist. I think it was cocaine and they injected it into the spine, and probably for about 10 minutes the bloke would be dead from the waist down.So Coates performed this operation, which surprisingly wasn't gory. He explained what he was doing; how he did it, and I can always remember this bloke laying back there and Coates was smoking this cigar and he had a big ash on it.And he said, ‘Excuse me Doc, that's not too hygienic is it?’ The Doc said, ‘What's that?’, and he said ‘The ash you've got on the cigar’. And he took the cigar out of his mouth and flicked the ash off it and said, ‘Lad don't worry there's no germs on that’. Anyway, a lot of the poor buggers made it and some didn't.

As I said before I was a good swimmer and I used to take these blokes down to the river. It would be as funny as anything. They used to be trying to swim; the bloke with the left leg off would steer this way, and the bloke with the right leg off would go this way. I'd say swim straight to me and they'd kick one leg and they'd just go like that. Veer off to which ever side the limb was off.

At the end of 105 kilo word came through and all the troops, most of them off the railway, were transported over the line that we had built. This was a pretty hairy trip because everybody had been sabotaging the line, and that's not just running over flat country. You'd run right round mountains with bridges built into the side of the mountain. It could be a 50-60 foot drop, or possibly more.

We were all transported back by rail and we went into Thailand to a camp called Tamacan. Tamacan was near, as is known today The Bridge over the River Kwai. The Kwai-noi River is the correct name.

We were there for a few months and suddenly they decided that they would form the Number One Japan Party. We were selected according to our health. We were supposed to be the healthy ones of which there weren't many by then.I was among those selected to go and there was roughly 1300 of us. I’d lost quite a few stones in weight by then.

They gave us an issue of clothing which they had probably captured in Java or somewhere. Of course, a lot of it was ill fitting but anyway it was the first issue of clothing we had had since we were POWs and which we were thankful for. We then left Tamacan.

We went to Bampong which is the junction of the line between Thailand and Malaya. A big marshalling yard was there. Then we got a train and we travelled four hundred kilometres, which took us a couple of days. I remember we travelled all one night and stopped the next day at a Jap rail side kitchen and had a feed.

We went into Cambodia. At the border they changed engines because Cambodia was under the French. It was a French Protectorate. So the Thai engine stayed and they hooked on a French engine. We went through Cambodia and then we came to the Mekong River and they had these ferry boats which weren't too bad. They crowded us in like they had before.We travelled down the Mekong River. I think it was about a 12 hours, it might have been more.

When we got to Saigon we pulled up at this modern concrete wharf. The place was lousy with Japanese shipping. It was a Japanese distribution point and we worked there carting rice, unloading barges, putting rice into these warehouses. These bags of rice weighed two hundred pound. One bloke carried a bag of rice, two hundred pounds. I tell you what, they were damn heavy until you got the knack. You'd virtually run with it. You would get a rhythm. If you ever see a native carrying something like that he'll get up a jog and that's the secret of it. Once you got to know how to do it you could handle it quite easily.

We loaded ships from there with rice and eventually they said, ‘Alright all men go to Japan’. So they put us on this barge. A twelve hour trip down the river to Cape San Jaque which is right on the coast. They put us on a ship. It was a clean ship. A pretty modern ship. We stayed on deck overnight. We had a good feed, and then the Captain addressed us the next morning and he said he wouldn't take us to Japan as deck cargo, he wouldn't be responsible.

So with no alternative, we had to get back on the barges and go back to the camp in Saigon, which incidentally was the best camp we had ever had. It was a barracks for the French Indo China's Foreign Legion. While there we lived in relatively clean premises and had pretty good food. We all started to put weight on and recuperated and we were pretty good. The Jap who was in charge, he was responsible to take us to Japan, was quite happy to see us putting on weight so we would get to Japan looking pretty good.

Saigon remains memorable as that’s where we experienced our first air raid. We weren't far from the water, from the warehouses. One of these warehouses got a bomb on it and it was full of tobacco leaf and it blew it everywhere. Blokes were scrounging all this tobacco and rolling it into cigars and what have you.

While we were there we worked in various jobs. They had a lot of petrol dispersal areas. We rolled thousands and thousands of 44 gallon drums all over the joint. Some worked loading the ships on the docks, and various other jobs.

While we were in this camp in Saigon, the Japs came in with a writing pad or just a bit bigger. It was a French international telegram form, and of course paper was at a premium. Everybody grabbed the paper to roll cigarettes or toilet paper or what have you. Anyway, for me, I filled the bloody thing in, never thinking. I just said, ‘Address it to my father?’. I said I was OK and I was with this bloke I went to school with, Max Campbell. He was off the Perth and he had already been sunk in the Sundra Straits, and I met him in the camp. Unbeknown to me this message was sent. I've got the letter here today where a bloke picked it up in Western Australia. This bloke contacted my father and he sent the letter over. I'll show you after.

One day we were there and they said, ‘All men go to Singapore’. So we went. We went back up the Mekong River, through Cambodia, back to Bampong by rail from Cambodia through Malaya, across the causeway and into Singapore. We arrived there on American Independence Day, July 4th 1944.

The place was poverty stricken by then. They were in dire straits, starving the same as everybody else. All those sorts of places were such bustling sorts of joints when we were there, but now they were nothing. It was just like a ghost town.

We were put in the River Valley Road camp. We were only there for a few days and then they took us to an island in Keppel Harbour, that's the main harbour there. I don't know what the name of the island was but the bloke who was in charge of us, a Jap, was a little stodgy short fella and we called it Jeep Island. We used to go by barge across from Jeep Island and work digging a graving dock about 500 foot long by 50 foot deep. We used to work the night shift on it. This Jeep Island had no water on it. It was a terrible place. We worked on there for five or six weeks I suppose. I don't think it was ever used mind you. I don't think it was ever completed.

American submarine activity had been that constant around Saigon, and that's why they couldn't take us to Japan and brought us back overland.When we finished working on Jeep Island they said, ‘all men go Japan’. See, they were pretty well restricted in their shipping. They were losing a lot of shipping and shipping was a priority in order to get us to Japan. We eventually got back to River Valley Road. From there they marched us down to the docks and there were two ships there, the Rakuyo Maru which was the ship I went on, and the Kachidori Maru, and a lot of British blokes went on that.

There were 1300 Australians on the Rakuyo Maru. This was a vessel of about nine thousand tons. It was as old as me, had been built in 1922. It was just an ordinary cargo passenger vessel.

We were shoved into the hold, crammed in, which was bloody awful because we had already experienced sea travel when we went to Burma. The toilet facility consisted of a wooden structure slung over the side of the ship which you would straddle. The only washing facility was a salt water hose and they allowed so many on deck so you could get a bit of a hose down. They couldn't get them all in the hold, and they allowed some people on deck.

Fortunately for Max and I we were able to sleep on deck on these rafts. They were a wooden structure with ropes around the sides. They were only about six or eight inches thick. In the water if you got two blokes on top they would submerge. So really all they were was a floating square piece of wood which you could hang around the sides of the vessel.

We got on the ship and they pulled us out into the harbour and we stayed there for a day under extreme heat. Eventually we formed up in a convoy, I think of nine ships. We left there around September 10.

We travelled and got into the South China Sea where a couple more ships joined the convoy as escorts. We had one destroyer and the rest were corvettes. The destroyer was a pretty good sort of a ship. The others were only like little small corvettes. There was probably about six of them. These ships came out from Manila and joined us. They formed up in the convoy, and of course unbeknown to us, we never knew until after the war, the Yanks had broken the Japanese code and they knew when this convoy left Singapore. They had radioed a pack of subs; I think it was four submarines. They put them at intervals across the South China Sea. They worked it out that the convoy would have to come through and one of them would sight them. The Japs never had too much radar.

We only just settled down. It was probably the 14th of September and it was about the early hours of the morning, maybe two o'clock. A torpedo struck and took the destroyer out. She just went bingo and within 30 seconds the whole thing just broke in half and down she went. We saw that happen. It lit up the place naturally because it exploded.

The convoy then altered course and they tried to get away. Everybody was on tenterhooks and then it settled down. Then about five o'clock, it was just breaking daylight, the submarines got into position and attacked the convoy.

Max and I were sleeping on top of these rafts and of course we had all our gear with us on top there. We could see these two torpedoes coming. You could see them coming. One hit in the engine room and that stopped the ship. This ship was loaded with rubber, block rubber. When we went aboard the ship we had to carry a block of rubber up which had a handle made in it. We carried that up and they said it would act as a life preserver.There was no way the bloody thing would ever float. It would have gone straight down. It was just a big solid bit of rubber. It was just one way of the Japs getting extra cargo on the ship. Another 1300 bales of rubber sort of thing.Anyway, one torpedo hit the engine room. The second hit right in the bows of the ship.

It threw up a volume of water. It was just like being in the surf. The water came over and it washed us off the top of these rafts. It might have only taken a few seconds. Right in front of us were the winches, those big steam winches. It washed us over the steam winches - we didn't hit them luckily, and we just went straight up against the bulkhead of the main bridge, and just hit it like that, and then the water was gone. We were lying on the deck. Of course we lost everything. Everything we had was gone.

I said to Max, ‘What do you reckon?’ And he said, ‘I don't know. It seems to me that this ship's going to float’.So we started throwing these rafts off, as we'd all been instructed what to do; ‘Don't just chuck them willy nilly. You might hit some poor bastard that's jumped off the ship’. So anything that was floatable we got rid of it, tossed it over. So to Max I said, ‘What do you reckon?’, and he said, ‘I think we should go. Everybody else is leaving the ship’.

So we left, and we were hanging on to one of these rafts. Of course, in the convoy we had an oil tanker and this had sunk. The water was alight and it was covered with oil. We looked like drifting into this fire. But Max and I were pretty good swimmers, and we said, ‘We're not going into this’. We looked back and we must have been well over a mile from the ship by this time and the ship was still floating so we decided to go back to the ship.

We asked everybody on this raft did they want to come back with us, and explained if they followed the instructions that we would give them then we would get them back. One bloke came with us.

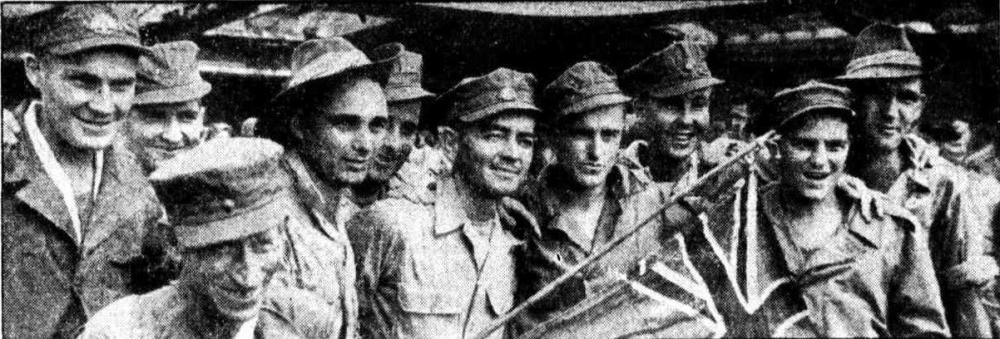

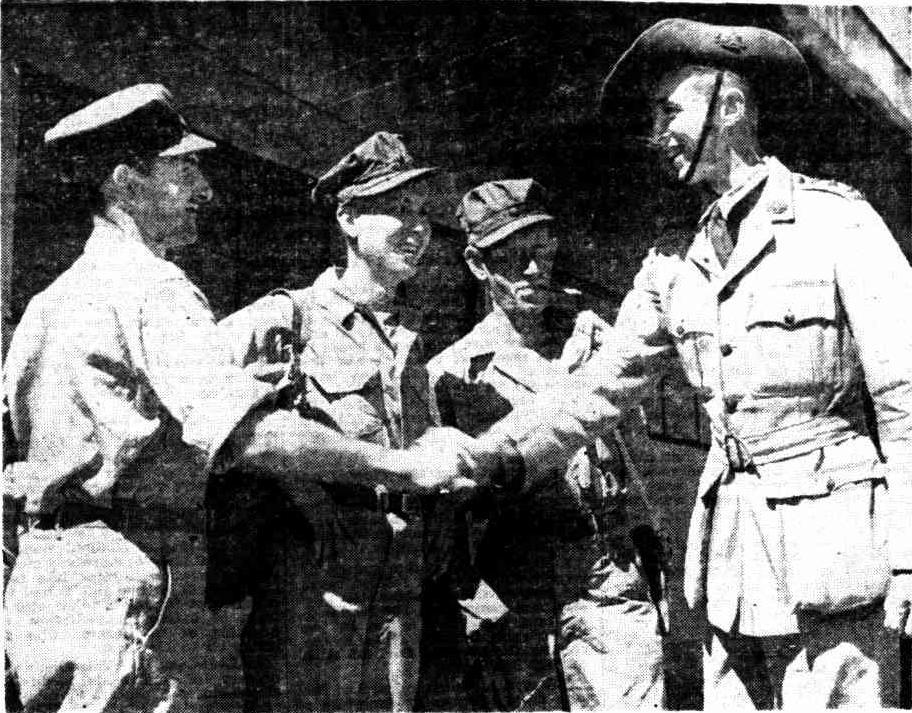

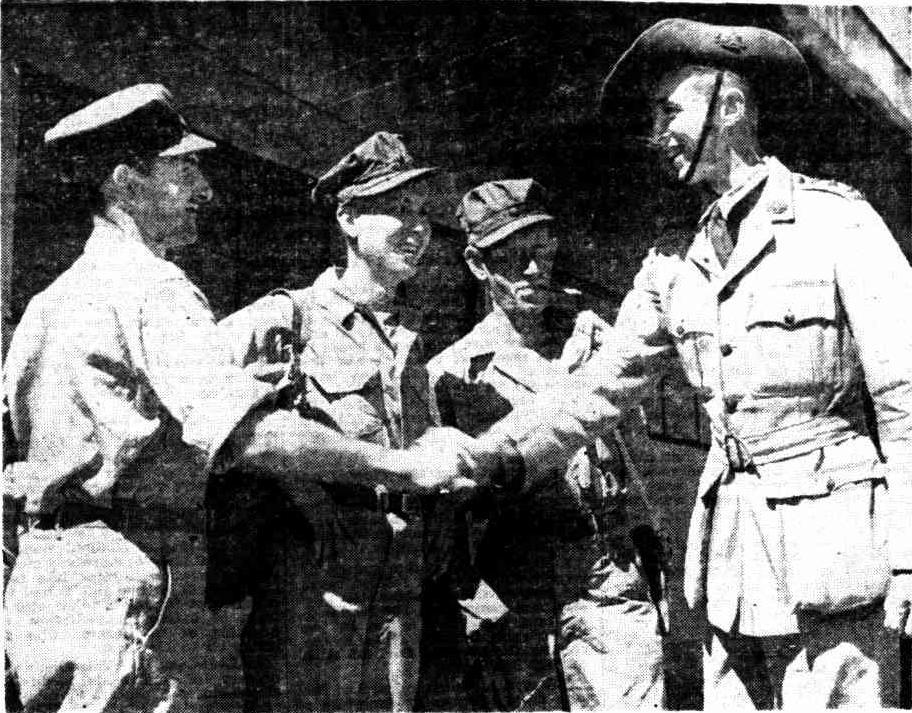

Former Australian prisoners of war are rescued by the crew of USN submarine USS Pampanito (SS-383). These men survived the sinking of two Japanese troop transports, the Kachidoki Maru and the Rakuyo Maru by Pampanito and USS Sealion II (SS-315) on 12 September 1944 respectively.

We got about half way back and got depth charged by these Japs who were aiming for the submarine. I had never been in a depth charge in my life before and it sort of hits you right in the stomach. Max said, ‘Quick get on your back. You should take it through your back. If you tread water and it hits you in your tummy then it can crush your intestines’.

We eventually got back to the ship. There was a rope ladder hanging down the side of the ship so we climbed up. When we got on deck there were some Japanese ‘comfort women’. The Japs took them wherever they went.

I'll always remember this bloke out of my unit, he was a lot older than me and he was bald headed like I am now, and he was in the nuddy. He was saying to this Japanese girl who was sitting on this step, ‘Everything will be right’ and I said, ‘Have a look at Yourself!’. All he had on was an AIF hat, so he whipped his hat off and put it over his privates. So funny, she didn’t seem bothered and would have seen more of that than hot dinners. He was so embarrassed!

Anyway, to cut a long story short, there were a couple of boats left on the ship. One had a hole in it so we patched this up, and with the aid of these blokes from the navy, the Japs had cut the ropes that were in the davits, we re-rigged it all and we launched this boat. Through experience, theoretically it should have gone down level over the side.

There's one mob on one end and on the other with ropes. We were supposed to be feeding it out, and it got away from somebody and it fell down and jammed, and all the stuff we had scrounged from the ship, (we had been going through the ship getting what food we could, water and everything else) the lot fell out into the water.

Some bloke got a fire axe and he belted this big block and she busted and the boat went down and bang into the water. She came up right but it sprang all the planks in it. She was leaking pretty bad. From the time we got from the top deck down, we couldn't get in the damn thing. There were about 60 blokes in it, all sitting around the gunnels.

We cut these big timber structures – toilets made out of timber, long things from here to there, and ten or twelve foot long, and we tied this thing onto the boat.

Max and I spent the first night on that. In the morning they were constantly bailing this boat. The Japs were running around and they picked the Nips up. When the Japs took off they took all the boats you see.

So they went around and they picked up all the Nips. Incidentally we took this Japanese prostitute off with us. We had a devil's own job trying to get the Japs to take her. They didn't want her. Anyway eventually a boat rowed over and we got rid of this woman, and while they came over, they stood over us with a rifle and we had two barrels of water and they took one. They had been drinking it like it was going out of fashion.

We didn't know what was in front of us. We had to ration it. In the barrel there was a little vial, a metal vial maybe one or two inches round and four or five inches deep, and we would dip that in and have one in the morning and one at night.

The next morning you could see a couple of empty boats. We swam over, got a couple of boats, rowed back, got rid of this bloody leaky thing and we split it up. There were about 30 blokes in each boat. Of course we took a lot of blokes. We pulled them out of the water. They'd get into this boat.

We had a bit of a sail. We decided that we'd head due west. We knew we were somewhere between the Philippines and the China coast. We didn't know how many miles away, so we reasoned that it was a big hunk of land, allowing for currents and everything else we were heading due west so we might hit the land somewhere. Anyhow the other boat went the other way towards the Philippines and we never heard hide nor hair of them again.

I think it was the evening, about five o'clock in the evening and we struck Brigadier Varley. Varley was the most senior officer on the railway and he was getting transferred from Formosa into an officer's camp there, and he would have been with 150 blokes, all in boats. They were all tied together and we sighted these blokes and we went over.

He said, ‘What course are you on?’ and we said, ‘We're heading due west’. He said, ‘We're heading northwest, do you want to come with us?’. It was only fate, two boat loads of us, and we said ‘No, we'll go on our own’. So we left them and the very first light the next morning we heard all this machine gun fire. You couldn't see anything because when you're in a lifeboat your horizon is limited. If it was ten stories high you could probably see ten miles, but we couldn't see anything but we could hear all this machine gun fire.

Over the horizon came the top of this mast and it gradually increased and it was a Jap corvette. They never stopped. It was still going, and they sang out, ‘Are you American?’ ‘No’. ‘Are you British?’ ‘No’. ‘Australian?,’ ‘Yes’.When we said ‘Yes’ they threw these scrambling nets over the side. We came along side and we grabbed the nets and we went up like monkeys onto this corvette, and they shoved us out on the bow of it.

When we got on this that we could see two other corvettes, and we said to the Nips, ‘Where are all the other blokes?’ knowing they couldn't be that far away. I mean they would have been within the horizon of the ship because we had only drifted over night. They pointed to these two other ships, so we naturally assumed that they had been picked up, but we never heard anything more from them, and we maintained, the survivors maintained, they had been done over by the Japs, and we were picked up more or less so they could save face by saying they had picked up survivors from the convoy.

We travelled all day and night and during the night came across a ship which had been torpedoed. It was on fire. The corvette came right up to the ship, I presume looking for survivors and at the time I thought this fella's taking a hell of a risk because we'd be silhouetted against the flames.

Lucky for us nothing happened. There were no survivors so we pushed off and landed the next morning at Hainan Island which is a big island off the coast of China. When we disembarked off this corvette, they put us on an oil tanker and that's when we caught up with the British survivors off the other ship which was carrying POWs and had been sunk later than us.

These blokes were in a pretty bad way. They were burnt and had broken limbs and what have you. Anyway, that was the closest. We were only anchored about a mile off shore. Everyone was very apprehensive. We didn't want to go to Japan on an oil tanker because we all knew we would never have got there if we got attacked. Anyway the Japs must have read our minds because they put a couple of machine guns on this thing and told us that if we go they would open up.

Luckily for us some Jap officer came aboard, a Lieutenant Lamada who was in charge of us to go to Japan and he realised himself that there was no chance of us getting through. He went and made the necessary arrangements apparently, and they pulled us off this thing and put us on a whaling ship. It was a pretty large ship where they could pull a whole whale up into the ship and do whatever they do with it.

We left there for Formosa, which is Taiwan today, and I think there were two or three ships in this convoy and we were the only ones to get through to Formosa. One of the escorts which got hit had all the windows blown out of the bridge. I think that the corvette took the torpedo which was aimed at this ship that we were on. Anyway, we got to Formosa and they had two or three attempts to get out of Formosa. We'd go out and they would probably get submarine activity on their Asdic and they'd come back.

By 1944 the Japs must have lost a hell of a lot of shipping. We had never given up hope. That was the only thing that kept us going. We knew we were on the winning side then, things had turned in our favour.

We knew we may get torpedoed again but we were also aware we were expendable. These ships weren’t marked with red crosses or ‘POW’ to indicate they were carrying POW’s you see, so the American submarine skippers didn't know we were on the ships. We were just fair game, part of what would apply to any bombing raid.

We eventually got to Japan, arriving at a place called Mugie which is on the South Island of Japan. We got off there. All the gear we had, was... like our underclothes. We only had a pair of underpants. It was bloody cold then in Japan. They put us through all these delousers. They put us in cement tanks filled with hot water, and there was a bloke with a rod and he'd hit you on the head and push you down under the water. Anyway we all got dunked and they came out and disinfected all our gear, and we just stood in this room. We had no towels or anything. There was no provision made for us whatsoever.

There was about eighty of us. They took us by rail then which is under the sea, you come up on the main island. Then we finished up in Kawasaki, which is a precinct I suppose of Yokohama. While we were there, we had a camp; I suppose it was a couple of miles from the factories where we worked, and that was the idea of us going there in the first place. All their civilians had been called up and of course they were running short of labour. The idea was for them to recruit 10,000 POWs and take them to Japan.

We worked in this factory. There were roughly about 10,000 employees, mostly Japanese people, working in this place. It was all heavy milling, castings and all that sort of thing, but what ever we made God only knows where it ever finished up. Nothing was ever assembled into one final motor or what have you. There were a few Americans and British there when we arrived but I think most of our camp was Australian. We were under Japanese civilian foremen, had Japanese guards and the guards would march us down to the factories and then we'd be taken over by these Fumen I think they called them; civilians recruited as guards and employed by the factory.

I think by the time we got to Japan about six months had elapsed since the Japan Party was announced. The bombing started then, around March 1945, and that continued right up until the end of the war. So that was September. In that time we were in the fire bombings by the American B22's. One particular raid, the whole of the place was alight and they had us up on the roof putting wet blankets on the tiles to stop the sparks. Up on the roof you could see this fireball coming and no way in the world could you ever stop this. So they realised that we had to get out.

The Camp Commandant he sort of led the way, opened the gates and out we went. The civilians were outside and hostile to us which was only natural.It looked pretty dicey at one stage like they were going to do us over. This one bloke drew his Samurai sword, I don't know what he was going to do, but he waved it around his head and they sort of parted, and we went like the clappers.

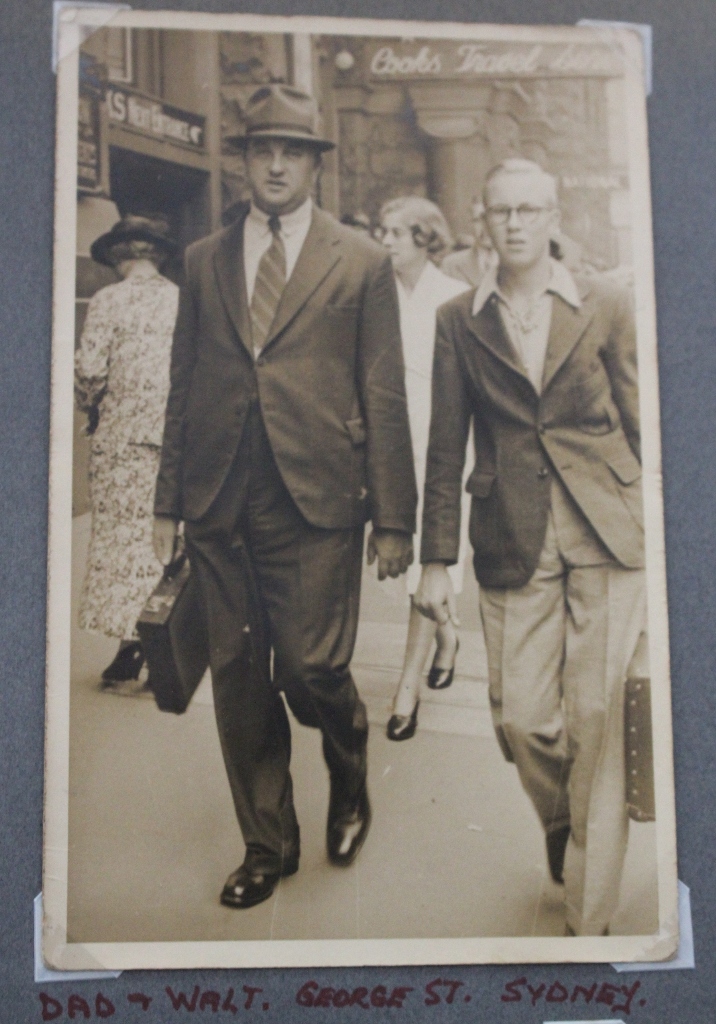

When we got out, we thought ‘Where the hell are we going to go?’ We weren't familiar with the country, with the township. It would be like in Sydney. You wouldn't know whether to run up George Street or down Pitt Street. So we followed these guards.

I can remember going over bridges, there's a lot of canals there in Japan, and all these women and kids were all in these canals, and of course they wouldn't have made it, with all these fire balls. It creates its own fire and it sucks the oxygen out, and these people would all have been killed.