Victor Daley Timeline

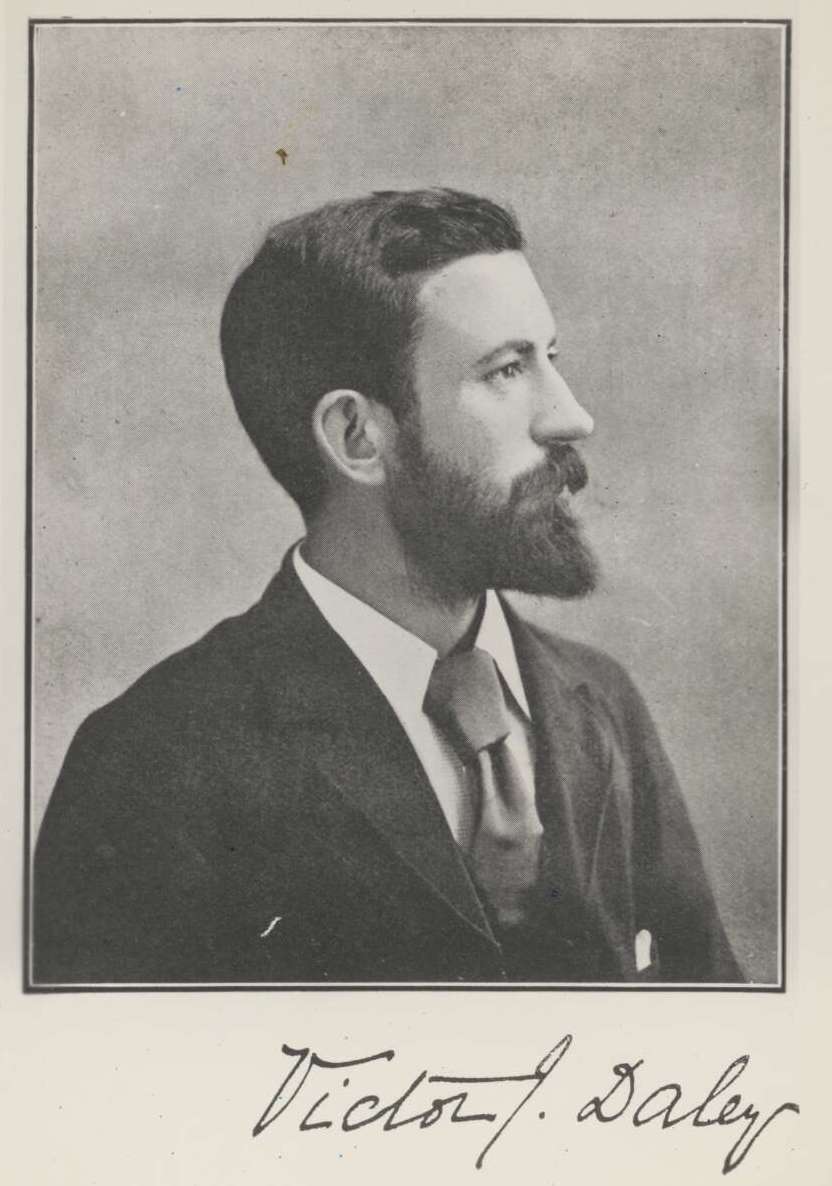

Mr. Victor J. Daley.

A new poet is, undoubtedly, amongst us, in Mr. Victor J. Daley, and, although he is an Irishman by birth and education, his muse has developed in Australia, and it may be supposed that he will take his place among the " Australian poets " like Stephens and Gordon. A Brisbane lecturer has been comparing Mr. Daley to Persian poets of the classical age. Some still think that the comparison is violent and far-fetched, and most people trill be unable to make the comparison for themselves. However, Mr. Daley trill bear judgment upon his own merits by British people who understand the genius of their own language, and appreciate the development of the poetic faculty in the imaginative Celt and the philosophic Saxon.. Mr. Daley can afford to stand his trial in Melbourne or Brisbane, without having the venue changed to Astrabad or Teheran.

Mr. Daley was born in 1858 at Navan, within two miles of the City of Armagh, in the county of that name, and North of Ireland. Armagh city is celebrated as the place where St. Patrick erected the Primatial See of Ireland, and to the present day the Catholic Archbishop of the See is called "Primate of All Ireland," while the prelate of Dublin takes the title of "Primate of Ireland." These titles were settled many centuries ago, by the Sovereign Pontiff as the final solution of a difficulty between Dublin and Armagh respecting the Primacy of Ireland. St. Patrick was the first Bishop of Armagh, about the year 444. For the first time in the history of this ancient See, a Roman Cardinal (Logue) now fill its primatial chair.

Adjoining Mr. Daley's birthplace is the townland of Creeve Roe (Irish for Red Branch), which was the headquarters of the famous Red Branch Knights alluded to in Moore's melody :- .

Let Erin remember the days of old,

When her kings, with, standard of green unfurled,

Led the Red Branch Knights to danger.

Navan and its neighbourhood is rich in most interesting antiquities. In a garden adjoining the residence of Mr. Daley's parents, an ancient crown or fillet was once dug up, and young Daley was present on another occasion when a bishop's bogoak crozier, with beautiful interlaced gold-work in the crook, was turned up by the plough in a field near his grandfather's house. These interesting specimens of early Irish art are now shown in Irish museums. " Navan Ring" is an ancient rath or castle, in the form of a beehive, surrounded by a foss, and which was used in bygone ages as a residence by Conor MacNessa, the Agammenon of the Irish Iliad -The Children of Usna. There are no windows to this "Irishman's Castle." Entrance was obtained by an aperture which, centuries ago, was built in, and Master Daley, on one occasion, was confined to his bed for a week as the result of an unsuccessful attempt to re-open this passage with blasting powder! These raths or castles were not used to such treatment as young Daley bestowed upon "Navan Ring" for Irish warfare in the time of Brian Boru, and for centuries before, was conducted in the open, and victories were obtained by fair fight or strategy.

Mr. Daley was educated at the school of the Christian Brothers in Armagh. At the same time, by-the-bye, Mr. W. H. Irvine, the present member of the Victorian Assembly for Lowan, was a pupil at the Royal School in the same town. Mr. Daley's father died when the son was only six years old, and his mother re-married. Young Daley's mother and step-father then removed, when the boy was 10 years old, to Devonport, in Devonshire, England, where, in 1840, the great fire took place in the dock-yard, whereby the Talavara of 74 guns, the Imogene frigate of 28 guns, and an immense quantity of stores were destroyed. On that occasion, the relics and figure-heads of the favourite ships of Boscawen, Rodney, Duncan and other naval heroes, which were preserved in a Naval Museum, were also burnt; the total loss being estimated at £200,000.

Young Daley went to the Catholic school at Devonport, which was first under the supervision of a Rev. Mr. Hobson, who had formerly been an Anglican clergyman. Father Hobson was a man of private fortune, who spent nearly all his means upon the Catholic Church and schools of Devonport, where his congregation was small and not rich. He was succeeded, in young Daley's time, by a Father Verdon, also a convert to Catholicism, and a man of large private means, which he, like Father Hobson, devoted to religion, education and charity. Master Daley remained at Devonport twelve months, at the end of which time he was sent back to Navan to become the charge of his maternal grandfather and grandmother.

Master Daley returned to the Christian Brothers School at Armagh, and continued a pupil of the school for the next three years. In these days' young Daley was a frequent visitor to "Navan Ring." It was popularly believed that this rath was a home of the fairies, and often, when Daley and some young companions went there rabbitting with their greyhounds, Victor would put his ear to the ground to hear the fairies' music below !

For, it was said that if one heard the music, it would remain with one for life!

Victor Daley frequently heard (in fancy) this subterranean harmony, and, no doubt, this accounts for the development of the poet in later years ! Be this as it may, the boy showed a love of poetry some time before his departure for England in 1868. When only eight years of age he borrowed Byron's Cain from the Christian Brothers' Library, and deposited it, -with some other books, in a haystack at the back of the family residence for occasional private use. His grandfather disapproved of his reading much at that age, and so little Victor had to indulge his literary tastes by stealth. Some boys would have liked to borrow Cane from school and forget to return it!

One day when little Daley was returning from school-he was now about 12-he made a distinguished acquaintance, whose cicerone to the home of the fairies he became. He and some other boys were having a game of marbles on the road when they were joined by the Primate, Dr. McGattigan, who, at the close of the game, called for a volunteer to show him the rath of "Navan Ring"; young Daley led the tall, stately but kindly Primate to the rath, and pointed out the stone (still bearing the trace of Daley's blasting powder), which, according to The Booh of Armagh, marked the entrance to the ancient castle. From the rath, the Primate was led by little Daley to his home, and introduced to-the boy's grandmother, who was paralysed with awe and delight, at the unexpected advent of such a distinguished visitor.

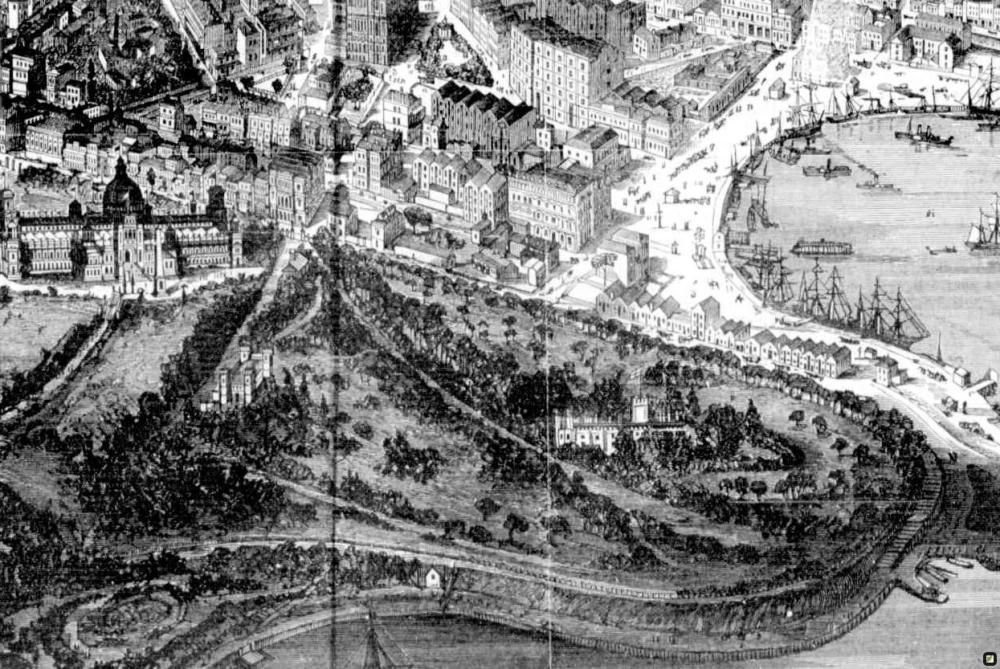

In 1871, Master Daley returned to Devonport, and in the following year he lost his mother by death, when he was only 14 years of age. His step-father, Mr. Moore, married again. Master Daley continued at school in England till 1875. He passed an examination for a junior clerkship in the service of the South Devon, now the Great Western, Railway Company, and obtained an appointment from the company. The scene of his duties was in Plymouth, to which he, at first went daily from his step-father's home in Devonport, but, after awhile, he took up quarters in the fortified seaport, which in 1588 was the rendezvous of the English Fleet, of 120 sail under Howard and Drake, where Sir Francis played .his- famous game of bowls as the Armada came up the Channel, and whence Drake and his comrades chased the daring Spaniards from British waters. Mr. Daley remained with the South Devon Railway Company for three years, and in 1878 sailed from Plymouth for Sydney, New South Wales, although he had some connections by marriage in South Australia.

Mr. Daley was not long in Sydney before he found himself very "hard up." He determined to take any employment that presented itself, and seeing an advertisement for a gardener in one of the morning papers, he answered it. He was asked to call, and found that the person who wanted a man to take charge of his garden was the Rev. Mr. Stephens, a well-known Anglican clergyman, who kept an academy for boys in Darlinghurst-road, and died a couple of years ago. Mr. Daley got a smattering of gardening from his employer, and successfully concealed his own entire ignorance of horticulture. His sleeping apartment contained 200 or 300 volumes of books, confiscated by Mr. Stephens from his pupils, and Daley spent most of his time among these. He lived an Arcadian life, with an income of £20 a year and "found," for one consecutive week ! During the second week, he was "under notice"! In point of fact, the engagement was a terrible failure. Besides looking after the garden, Mr. Daley had to clean the boys' boots and help the cook! He got on well enough with the flowers, but in trying a new method of drying three plates at a time, he broke a lot of the crockery ware, and he supplied to the table eggs of a rare breed of fowl, many of which contained birds, and were never intended to be eaten. Mr. Stephen sent for Daley at the psychical moment when Daley had asked to see him. Mr. Daley silenced the dominus by tendering his resignation at once and crying quits as to wages. The resignation was accepted, but the wages were paid. Mr. Daley left Sydney, immediately, for Adelaide.

In the South Australian capital Mr. Daley was an attorney's clerk in the office of Messrs. Pope and King, King William-street, for five weeks, and then corresponding clerk in the counting-house of Messrs. Harris, Scarfe and Company, in Gawler-place, for nearly a year.

He had, by this time, saved a little money, and he and another determined to go to Japan, via Melbourne, and try their luck under the rule of the Mikado. On reaching Melbourne they changed their minds and agreed to go to Fiji instead of Japan. Just then a big race-meeting was on in Melbourne, and Mr. Daley and his companion went to the races at Flemington one day. When they returned in the evening, they decided that they must remain in Melbourne. The astute reader will, probably, guess why Daley and his chum then parted company.

The former fell in with a dealer in second-hand books, who did business in Carlton, and with whom he went to lodge. He knew the value of books, and was of good service to the dealer, who was ultimately instrumental in bringing out Mr. Daley as a writer. One morning Mr. Crowther drew Daley's attention to a new local paper having made its appearance in Carlton-The Advertiser, of which Mr. John Whitelaw was the proprietor. Races were coming on, and Mr. Daley, appeared one morning at daylight out at Flemington in the character of a tout-a turf prophet!-although, as he afterwards declared, he knew the difference between a cow and a horse only by one having horns and the other none!However, he fancied he spotted a winner! The horse was a very long one, and it occurred to Daley that the horse's mere length would win him the race if he got anything like fair play. A few such horses, put one after another, would go round the course !

Daley returned to town, and wrote an article on the horses entered for the chief events at the races, which was accepted and published. This was Victor Daley's debut as a journalist and author ! He subsequently saw Mr. Whitelaw at the office in Elgin street, and became regularly attached to the Advertiser. After a few months, he was joined on the staff by Mr. Tom Power and his dog, "Mister." Mr. Power is now one of the chief sporting writers on the Sydney Morning Herald. Of "Mister's" subsequent movements we know nothing. Daley remained with the Carlton Advertiser about a year.

He was next employed in the Melbourne International Exhibition of 1880-1, where he had charge of some of the exhibits for the representative of some British and American manufacturers; but he was a shocking poor salesman, and this engagement lasted only six weeks. Daley had a friend, one Larry Blank, who had been "knocking about" the goldfields of Australia for 20 years, and he told Victor that whenever he saw “a good thing " he would wire to him. Just when Daley was about to start for Temora which was then in full swing-with Edwin Asterisk; a violinist and piano tuner, he received a brief wire from Blank telling him to come on to Queanbeyan.

The pair went by rail to Seymour, and walked to Albury where Asterisk received a remittance of £1-the proceeds of the sale of his fiddle. While camping a little beyond Albury, they picked up an ex-Captain of Lancers, who had been discharged from the Victorian Civil Service on Black Wednesday,' and was now on his way to seek work at Yanko, where he had heard there was a plague of burrs! He changed his mind, however, and joined company with Daley and his friend and the three journeyed through Wagga, across the Murrumbidgee, by Tarcutta and Adelong to Tumut, meeting with numerous adventures on the way-some serious, others ludicrous. They were lost in the Tumut Ranges for three days. Weary and famishing, they tried to catch some mountain sheep, but the musician was nearly trampled to death by a horde of the animals. At length Asterisk came upon a faint horse- track, which brought the trio to the banks of the Murrumbidgee. There the Captain swearing at large, laid down to die of hunger and exhaustion. Daley and Asterisk swam the river, and came upon a squatter's station, where they were hospitably received and given an abundance of provisions, with which, they hastened back to the Captain, who became refreshed and strengthened, and was soon able to resume the journey. They parted with the Captain at Yass, where, knowing something about horses, he secured a billet in a stable.

Daley and Asterisk at length reached Queanbeyan, but found that Larry Blank had, while on his way from Cooma in a comatose condition * aimlessly sent the wire to Daley in passing through the town! Daley, however, got employment in a tannery at 15s. a week, with board, lodging and washing. His duties were to drag skins or "pelts" across a yard, throw them into a pit and trample on them. Before he entered upon his office, however, he got an offer from the editor of the local paper - the Times-of literary work, at precisely the same remuneration as he was offered by the tanner; and as Daley preferred jumping on borough councillors and police court "beaks," in the columns of the local press, to trampling upon pelts in a tan-pit, he accepted the editor's offer. Asterisk was made bandmaster of the local band.

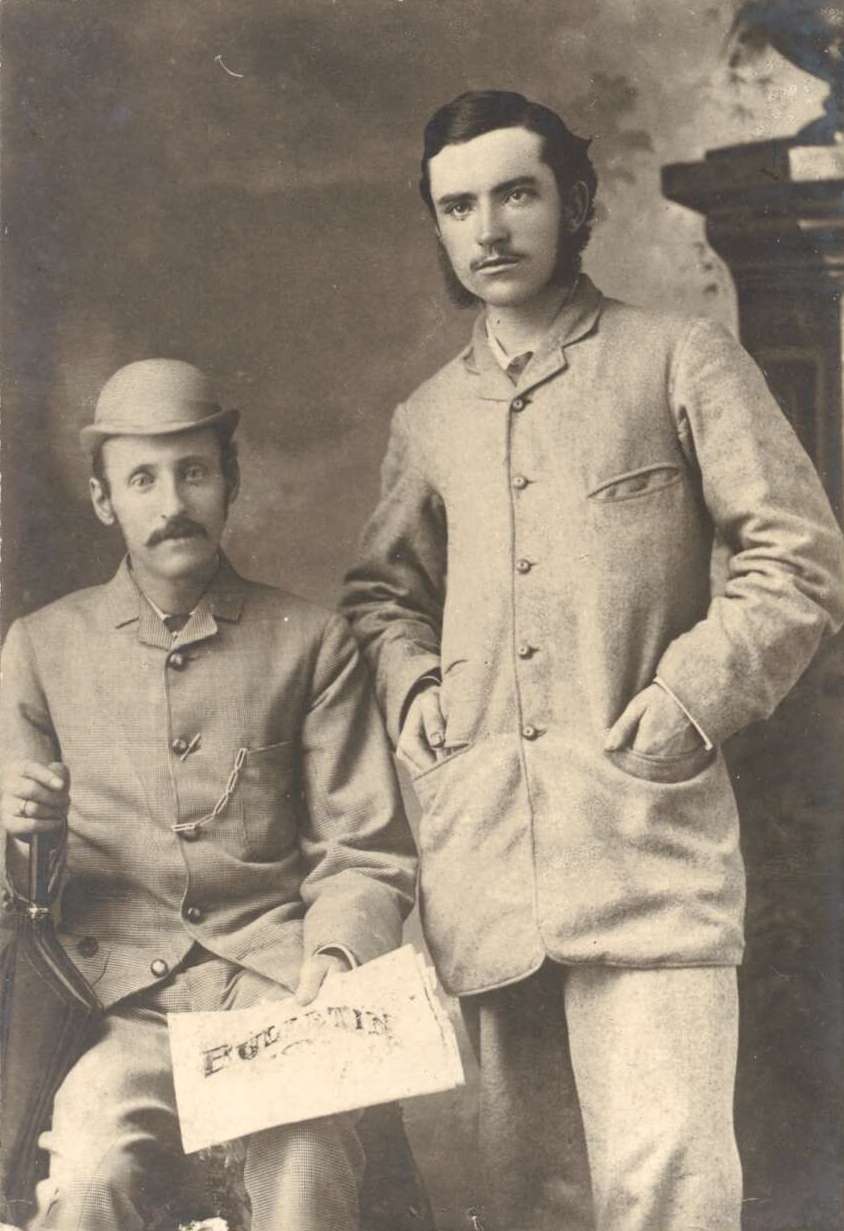

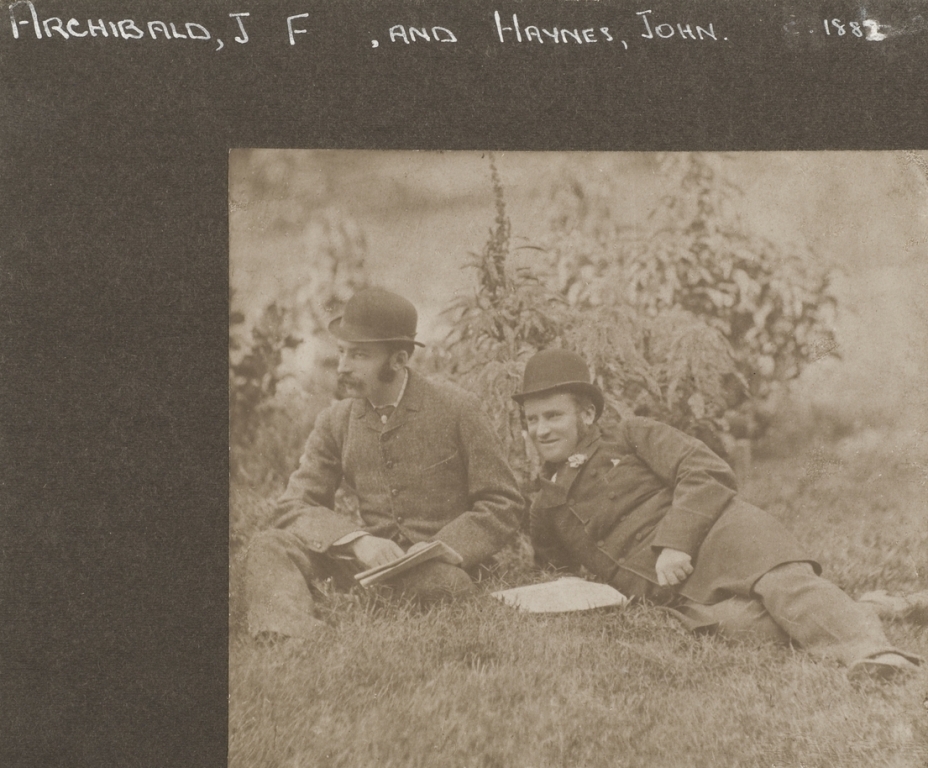

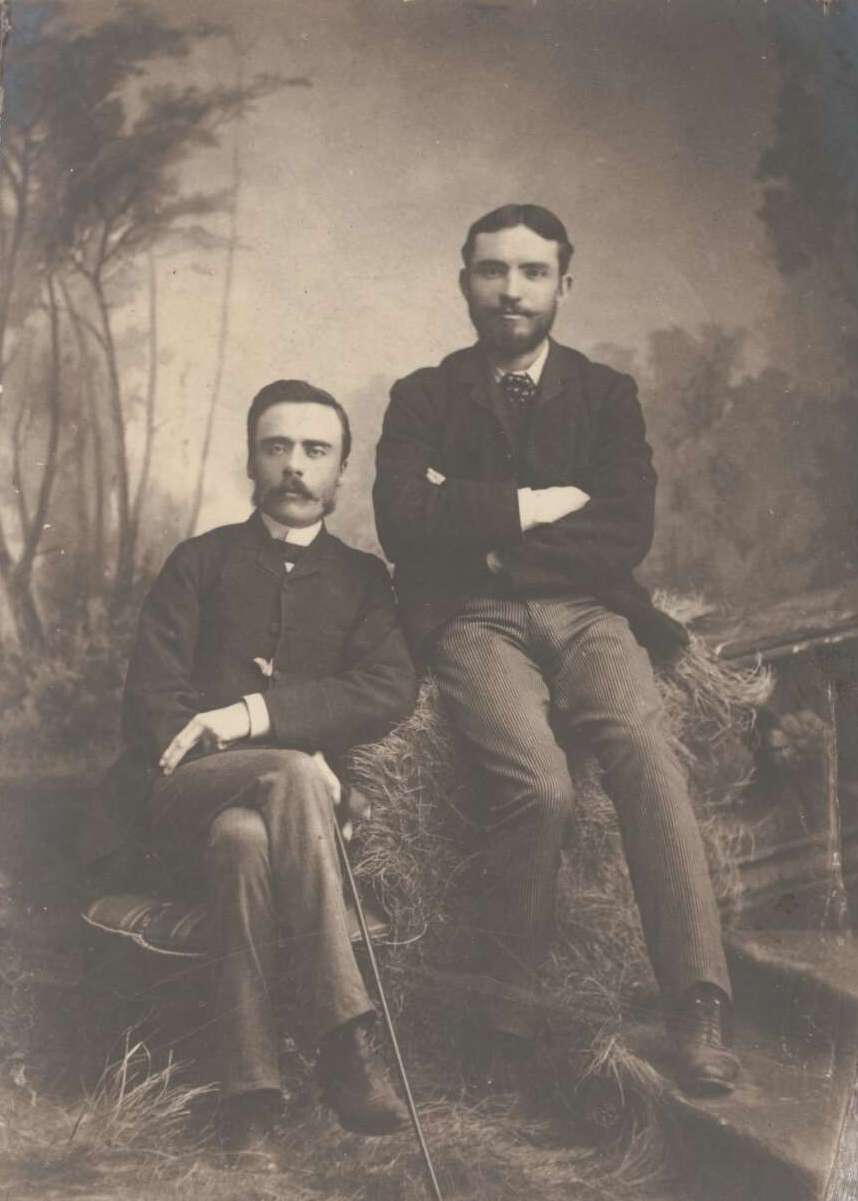

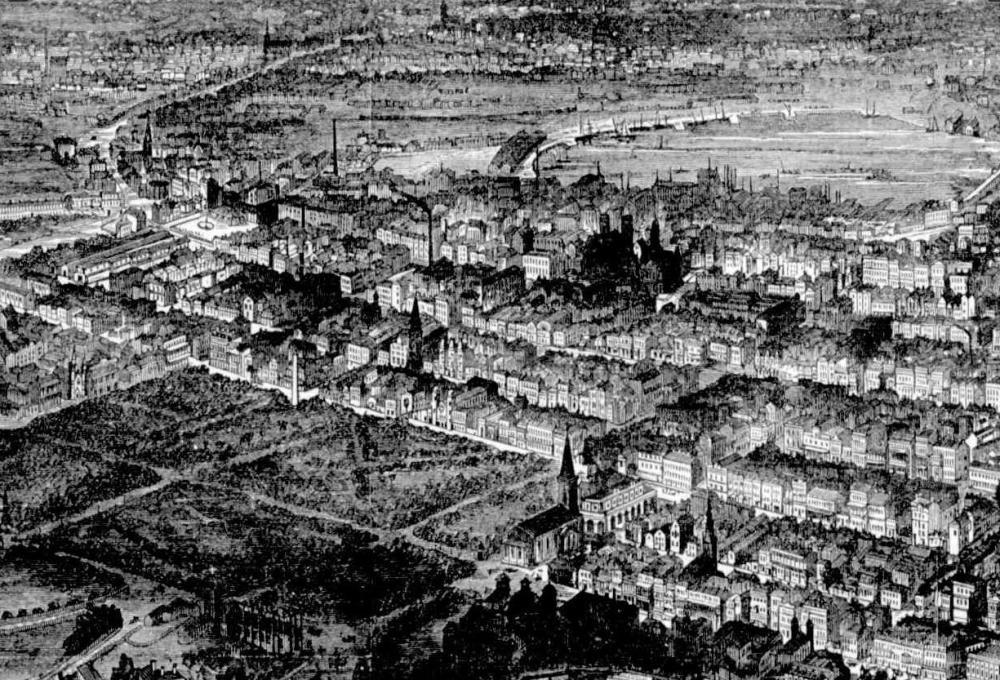

Victor Daley remained five months at the Times office, in the latter half of 1881, he then went on to Sydney, and joined the staff of Punch,which was edited at that time by Mr. Berdoe. Some time in 1882 he became attached to the staff of the Bulletin when Mr. W. H. Traill and Mr. J. F. Archibald were the editors and Mr. "Jack" Haynes was the manager. Mr. Daley stayed at the Bulletin office till 1885. In the meantime Messrs. Haynes and Archibald were incarcerated for a lengthened period in Darlinghurst gaol for non-payment of damages and costs in connection with the celebrated "Clontarf libel," and Mr. Daley frequently visited his chiefs in durance vile.

In 1886 Mr. Daley returned to Melbourne, and has since been a "freelance" in Australian literature, where no name is more familiar than his. He is a constant and valued contributor to numerous Australian publications scattered up and down the Australian colonies. He is about to publish his collected poems in volume form. In person, Mr. Daley is of medium height and build, youthful appearance, though he wears a full brown beard, and speaks with a slight North of Ireland accent. He is a capital story-teller, and a typical Bohemian. Mr. Daley is married, and has a small young family.

This is hardly the place to enter upon a detailed criticism of Mr. Daley's work as a poet. Let him himself. Here are a few specimens of his varying styles:

The following is a piece giving the spirit of what the Germans call Wanderjahre-the primitive nomadic instinct which is in the blood of all men, but suppressed by civilisation in the great majority, and which is quickened in the season of spring.

A Song of ROVING.

"When the sap runs up the tree,

And the wine runs o'er the wall,

When the blossom draws the be»,

From the forest comes a call

Wild and clear, and sweet and strange,

Many-toned, and murmuring

Like the river in the range

'Tis the joyous voice of Spring!

O arise, arise light-hearted !

Take pilgrim staff In hand

For it is the time for roving

Through the green and pleasant land.

On the boles of grey old trees,

Lo, the flying sunbeams play

Mystic, Boundless melodies !

A fantastic march and gay

But the young leaves hear them-hark

How they rustle ev'ry one !

And the sop beneath the hark,

Laughing, leaps to meet the sun !

Then arise, arise and follow,

The music goes before.

For it is the time for roving

Though we should return no more.

O the world is wondrous fair

When th« tide of life's at flood,

There is magic in the air,

There is music in the blood,

And a glamour draws us on

To the Distance, rainbow-spanned,

And the road we tread upon

Is the road to Fairyland.

So arise, arise companions,

As quickly as ye may I

For it is the time for roving

O'er the hills and far away.

Lo, the elders hear the sweet

Voice, and know the wondrous song,

And their ancient pulses beat

To a tune forgotten long,

And they talk in whispers low,

With a smile and with a sigh,

Of the years of long ago,

And the roving days gone by.

Then arise, arise, dear comrades,

While brightly shines the bun,

For we'll go no more *-roving

When the roving days are done.

Mr. Daley has written a good deal of elegiac verse. From an elegy, entitled "Love Laurel," on the poet Kendall, published in the Sydney Freeman's Journal (in which Kendall's own best poems appeared) the concluding stanzas are quoted :

Let be; lie still: thy songs and dreams are done.

Down where thou sleepest, in earth's secret bosom,

There is no sorrow and no joy for thee

Who canst not see what stars at eve there be,

Nor evermore at morn the green dawn blossom

Into the golden kingflower of the sun

Across the golden sea.

But linply there shall come in days to be .

One who shall hear his own heart beating faster,

Plucking a rose sprung from thy heart beneath,

And from his soul, as a sword from its sheath,

Song shall spring forth, where now, O silent Master,

On thy lone grave beside the sounding sea

I lay this laurel wreath

Mr. Daley has produced much love-poetry, of course. Every singer "worth his salt" must write, at least, a barrow-load of this in his time ! Most of Mr. Daley's poems of this description are too long for quotation now...

Here is an example of poetry of a devotional character:

SUNRISE.

Up rose the sun upon a chill grey morn,

And down the dim lands rolled

His serried rays upon the ripening corn

Bed gold on the pale gold.

Bright-faced was he as victor in the breach

Of some proud city won,

Who plants on high, beyond the foeman's reach,

His golden gonfalon.

The pale moon, gazing at that wondrous sight

As at the light of grace

A dying saint-went down into the night'

With glory on her face.

So, when the last sad hour has come for me,

Ere the dim path be trod

May I while darkness close round me see

The glory of my God.

A few samples of epigrammatic verse

LOVE'S LOGIC.

Corinna calls me heartless. Thus, you see.

Logic in love has little part.

How can I otherwise than heartless be

Seeing Corinna has my heart

THE ASCETIC.

The narrow thorny path he trod : .

"Enter into my joy," said God.

The pale ascetic shook his head,

" I've no heart left for joy," he said.

Mr. Daley has written a number of songs, one of which, "The Dell of Dreams," was set to music by Mr. John Delaney (now organist of St. Mary's Cathedral, Sydney) and published. Another, " If I were young as you Sixteen," was set to music by that eminent composer, the late Charles Packer, but owing to his illness and subsequent death was never published. * .

He has written an abundance of humorous verse, but fair examples of this style are too long for quotation. All Mr. Daley's distinctively Australian poems, such as " His Mate," " The Golden Bullet," " The Old Wife and the New," " Bryan Ryan's Ride," and " Larry," are of considerable length.

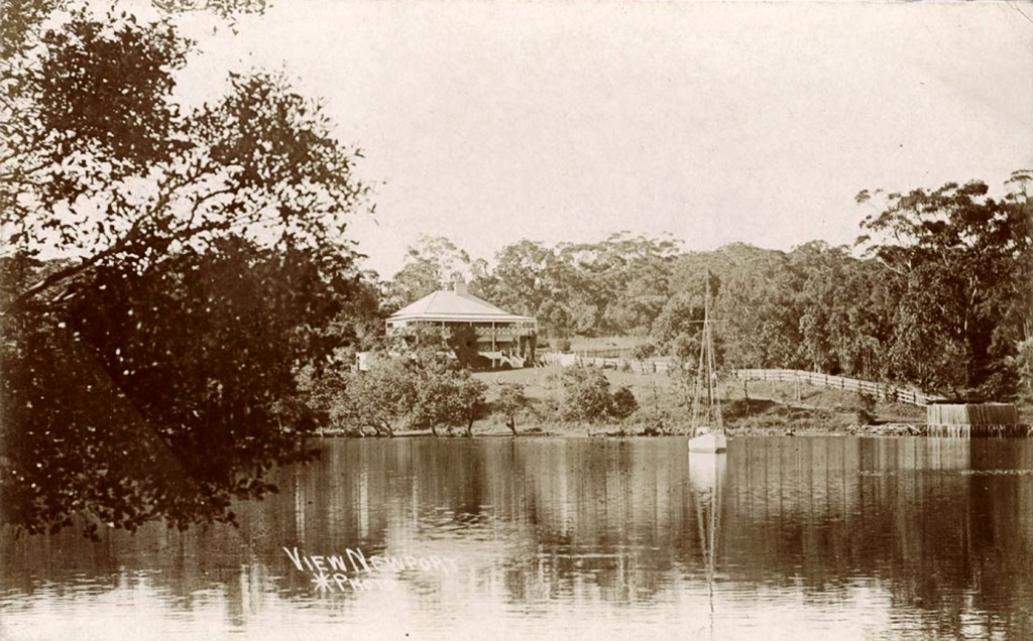

He has published portions of a poem, the scene of which is laid near the Hawkesbury River in New South Wales. "Narora" is to be the title of this poem, which will, with a few others, make a second volume if the first volume about to be published is successful. "Narora" is entirely Australian in colour.

We conclude with a specimen of Mr. Daley's muse in the pathetic vein :-:

The Dead Child

All silent is the room,

There is no stir of breath,

Save mine, as in the gloom

I sit alone with Death.

Short life it had, the sweet,

Small babe here lying dead,

With tapers at its feet

And tapers at its head.

Dear little hands, too frail

Their grasp on life to hold;

Dear little mouth so pale,

So solemn, and so cold;

Small feet that nevermore

About the house shall run;

Thy little life is o'er!

Thy little journey done!

Sweet infant, dead too soon,

Thou shalt no more behold

The face of sun or moon,

Or starlight clear and cold;

Nor know, where thou art gone,

The mournfulness and mirth

We know who dwell upon

This sad, glad, mad, old earth.

The foolish hopes and fond

That cheat us to the last

Thou shalt not feel; beyond

All these things thou hast passed.

The struggles that upraise

The soul by slow degrees

To God, through weary days,

Thou hast no part in these.

And at thy childish play

Shall we, O little one,

No more behold thee? Nay,

No more beneath the sun.

Death's sword may well be bared

'Gainst those grown old in strife,

But, ah! it might have spared

Thy little unlived life.

Why talk as in despair?

Just God, whose rod I kiss,

Did not make thee so fair

To end thy life at this.

There is some pleasant shore,

Far from His Heaven of Pride,

Where those strong souls who bore

His Cross in bliss abide.

Some place where feeble things,

For Life's long war too weak,

Young birds with unfledged wings,

Buds nipped by storm-winds bleak,

Young lambs left all forlorn

Beneath a bitter sky,

Meek souls to sorrow born,

Find refuge when they die.

There day is one long dawn,

And from the cups of flowers

Light dew-filled clouds updrawn

Rain soft and perfumed showers.

Child Jesus walketh there

Amidst child-angel bands,

With smiling lips, and fair

White roses in His hands.

I kiss thee on the brow,

I kiss thee on the eyes,

Farewell! Thy home is now

The Children's Paradise.

* Plain "drunk" seems too brutally candid, I fancy;

Three Sundowners

By Victor Daley

Imagine yourself twenty years of age with all the world before you ! Not the hard practical world as you know it now, but a world fall of wonder, and enchantments, and benevolent magicians, ready to make your fortune for you with a wave of their wands when you have time to attend to them. Then picture yourself as a young man who has already achieved a high position in life as a member of the Glorious Fourth Estate — that Power at whose frown monarchs tremble, and Governments grovel in the dust. Would you not feel that life was worth living, and that what elderly people said about its hollowness was a senile calumny ?

Of course you would. Well, I was that sort of young man in the year — but we need not trouble about dates. I was then editor, leader-writer, art critic, musical and dramatic critic, police court reporter, Sunday sermon reporter, fashion reporter, sporting editor, and several other things in connection with a weekly paper which circulated all over a Melbourne suburb, and had readers even as far away as Bacchus Marsh.These latter were relatives of the proprietor, and, of course, deadheads, but still they were readers. And what they read, week by week, was what I had written. That was a fine thing to know. Fancy a multitude of people, like the sands of the sea for number — four hundred at least — being educated by one little man, not very long from school! It was an intoxicating thought. And it is but bare justice to myself to say that I gave them of my best. I did not insult their intelligence by writing leading articles dealing with petty local questions or parochial politics, but took them to a higher level and instructed their minds upon matters of world-wide interest. Bismarck was the Colossus of Europe in those days, but his knees of iron must have knocked together more than once when he read what I wrote about him in the Carlton Chronicle. It was a great time. I have never since had such a grand opportunity to deal with European politics.

Larry Spruhan came into the office one day, and gazed at me silently for a moment. He was a rather handsome man with a cast in one eye, which gave him the drollest and wickedest expression you ever saw. He used to look at you with this eye, from under the brim of his slouch hat, until he could make you do almost what he liked. As this chiefly consisted in asking you to drink, perhaps the task was not so difficult as it might seem. 'What are you writing about?' he said on this occasion. ' The Eastern question,' I answered with dignity. He laughed uproariously. Then, when he had finished, he spat into the waste-paper basket, kicked the office-cat from under the table, and remarked, ' It's time for you to get out of this. You think you're growing to be a fine writer, and a philosopher and all that. But you're' not. You're a young ass, and if you keep on as you're doing, you'll be an old ass, which is a much worse thing. Better come away with me. I'm going out prospecting. ' Prospecting for what ? ' I sneered, for I was sore over what be had said. 'Prospecting for gold,' he replied; 'Did you think I was going out prospecting for blanky mushrooms?' I told him somewhat stiffly that I could not see my way to join him at such short notice. Then he made me promise that if I received a telegram from him, stating that he had struck gold, I would leave everything and make my way to him. ''You won't have to battle,' he remarked cheerfully. 'I'll send you money enough for your fare, even if it's to Port Darwin.'

With that understanding we parted.

* * *

Weeks passed by, but I heard nothing from Spruhan. Meanwhile, Caddy, the musician, and I had come to the conclusion that Melbourne was no place for us to dwell in. He could only make an odd half-sovereign now and then by playing at parties and the like, and a coolness had arisen between me and the proprietor of the paper, because some of his subscribers had told him that he should devote more attention to local affairs, and give Bismarck a rest for a while. Things were at this pass when I received a welcome wire from Spruhan. It came from Queanbeyan and ran thus : — 'Struck it rich. Come along at once.' But he had sent no money, and it was a far cry to Queanbeyan. Moreover, neither Caddy nor I had any money of our own to boast about. We managed to raise a little, however — Caddy sold his fiddle, and I sold the only watch I have ever had in my life — and immediately bought a set of blue blankets, a three-quart billy and two pannikins. Caddy thought of buying a second-hand revolver but I said that I didn't think it would be necessary. The purseless traveller goes singing on his way. Anyhow, the Kellys had Keen caught some time previously.

We intended to take the train as far as Donnybrook and start our tramp from that point. For tramp it had to be. We might have saved money by starting from Melbourne, but we were ashamed to be seen trudging through the streets in open daylight with swags upon our backs. Our fashionable friends might see us, and there would then be a fine, story to tell. It is a pity that the conceit of youth is not a marketable commodity. If it were, what a fine start in life most young men would have !

* * *

A grazier whom we met in the train induced us to go with him as far as Kilmore. He said he lived there and would give us a light job for a day or two and pay us a quid each — to use his own expression. We were delighted, of course. This was luck from the start. It was not until we arrived at Kilmore that we discovered that our generous friend was intoxicated. When we got out at the station he lurched off on his own account. I tapped him on the shoulder. ' Are we to follow you ?' I asked, with an affectation of cheerfulness. He turned around and regarded us with a bloodshot glare. 'If ye foller me — I'll give ye in charge — ye pair of blanky spielers, ' he said. 'But you asked us to come here, and it's night now, and we must stay somewhere. Where are we to go ?' ' Go to h ___ ,' he replied, huskily, and staggered into the darkness.

Then we recollected that he had been helping himself at intervals from a black bottle during the train journey.

****

We stayed that night at the hotel, and in the morning met an affable local resident who showed us how to make up swags in proper bushman fashion. I had two new suits packed up in mine — a fine black suit, for wearing at funerals, and garden parties, and other special occasions, and a serge suit for ordinary wear.. 'What's this for?' he said, holding up the former at arm's length. ' Well,' I said, ' I thought we might, now and then, be asked to dinner or afternoon tea by a squatter, and I thought it would be well to be prepared.' The man eyed me for a moment — to see whether I was speaking in good faith or not, I suppose. Then he threw his head back and roared with laughter. And, still laughing and holding his sides, he went out of the room. ' I must tell Bill,' he said, 'Bill mustn't miss this for the world.'

Presently he came back with Bill — a tall, saturnine-looking individual with a saddle-coloured complexion and a leather band around his slouched hat. Bill didn't laugh. He merely smiled drily and said, ' I wouldn't worry about the squatters for a while yet, if I was you. And you won't-find any use for that kind of clothes where you're goin' ! Besides you couldn't carry 'em.' He brought a pair of scales and weighed the swag I had proposed to carry. Thirty-two pounds it weighed. ‘But I can carry that much,' I observed. ' Try it day after day, and you'll find out,' he said.

I may remark here that before we came to the end of our journey my swag weighed exactly fourteen pounds. I gave the suit away to these disinterested counsellors. About a year afterwards I met one of them— the man with the dry smile — in Sydney, and he told me with much humour, over a drink, that they had sold it to a local Chinaman and drank the proceeds. At Wodonga I gave away three new white shirts to a travelling tinker in exchange for a Crimean shirt. At Wagga I bartered away a pair of new lace-up boots for a pair of copper-fastened bluchers. I was, in fact, all through the trip like the traveller pursued by wolves who throws out his clothing, piece by piece, to be devoured, and is glad enough to escape with his life. After breakfast we were off on the road to the Lonely and Mysterious Bush. I may say that while we were in Victoria we rarely ventured more than a mile away from the railway line. And we actually believed that we were in the bush!

****

It was a pleasant delusion, all the same. The trees obsessed me. I had seen gum trees before, but never so many at a time. I did not like them at first. They gave me an eerie kind of impression, which can hardly be described If it were possible to imagine that the Vegetable Kingdom had a spiritual code of its own (and why not, for that matter?), I could have easily believed that these grey-green apparitions were spectres of green trees that had been damned for some breach of the Vegetable Commandments. But I grew to know them

better afterwards, and to discover that they have their own peculiar charm. We camped beside a creek on the other side of Avenel that evening, boiled our shiny billy for the first time, and made bush tea. I have drunk tea in Devonshire with the cream of the county in it, and tea in Ireland with my grandmother's favourite flavouring of black currant buds, and tea a la Russe, with a slice of lemon floating in the cup, and tea au rhum, but none of them could compare with the bush tea I drank that evening out of a pannikin. And afterwards, when we lit our pipes, and yarned beside the burning log — the first burning log is as full of poetry and romance as the first kiss— with the stars above our heads, and the trees keeping guard around us, we were probably as serenely contented as anybody can hope to be in this world.

* * **

We paid our way — that is to say, we bought our own provisions — until we came to Benalla. Then Caddy said that this real sundowning would, have to – begin. 'Not yet,' I said, and produced a pound-note, which I had reserved for emergencies, from the lining of my coat. We went into town; and changed it at a hotel. One drink apiece. It was little for drinking we cared in those fine days. Then we bought tea, and sugar, and flour, and some meat, and camped by the river Caddy used to attend to the cooking of the meat. I made the Johnny cakes. We had good digestions in those days. Anyhow, I was never fastidious with regard to food. Caddy was. He liked his meat cooked nicely, and when he found a shovel-blade in the road one day you would have thought that he had discovered a side of bacon, he made such a song over the affair. He spent an hour that evening in cleaning the shovel-blade with sand.

Make a fine substitute for a frying-pan,' he said. So it did— though being so thick, it was somewhat slow— for three days! Then he threw it away. I was waiting for this to happen, but I asked him what he meant by discarding an old friend in such a contemptuous fashion. ' Weighs seven- pounds,' he replied briefly. I knew that well enough. I had lifted it. But that was one of Caddy's idiosyncrasies. If he ever saw anything lying around loosely, which he thought might come in handy, he would hoist it on his back and hump it along for two or three days, until he got disgusted. Then he would throw it away and march along until he came across some other absurd article, which he imagined might prove serviceable. To make things worse for him he was an inventive genius. I carried my swag in horseshoe fashion, or simply over my shoulder. This was not good enough for Caddy. He said that I was a mere beast of burden who had no brains to use to find a way to make my burden lighter. He had the brains all right, and it would have been a delight to you to see his harness. He made up his swag knapsack fashion. Attached to his belt behind was a little wooden bracket, upon which his swag rested. That took some of the weight from the shoulders. Then he had cross belts, of rope that brought some of the weight to the front. Another attachment passed under his armpits. This he called the 'distributor,' and claimed that it distributed the strain of carrying the swag equally over the different parts of the body. It must have been a good idea, for it always took him at least ten minutes to get himself into harness in the morning, and nearly the same length of time to get out of harness at night, without counting the times we had to stop during the day for readjustment of the apparatus. I have noticed that a great many labour-saving inventions are constructed in this fashion. I respected that harness of Caddy's, but although he earnestly urged its merits upon me I could not see my way to adopt it When a thing is too complicated for your intellect to grasp without strenuous effort it is better to leave that thing alone. Anyhow, I could inspan and outspan in two seconds to Caddy's ten minutes. We boiled our billy on a blacksmith's fire in Barnawartha. Had tea in the forge. ' Do you know where there is an empty house we could camp in ?' ' Over there,' said the blacksmith, indicating the place with a huge grimy oratorical arm. There was a space of dry ground about four feet square in the mansion. The roof that might have sheltered us was gone, all but a patch. We lit a fire on the little oasis. I awoke in the morning and found myself asleep in a pool of water. Caddy was slumbering in another pool. 'This won't do,' I observed, 'we shall be getting rheumatism.' I tore down some dry panelling and started the fire again. Caddy went over to the main street of the city and bought a loaf with our last threepence. It was a gloomy breakfast. We were sodden wet, through and through. 'Plenty of exercise,' said Caddy, after he had harnessed himself. 'Circulate the blood, and keep yourself warm, and it's all right.' From Barnawartha to Indigo Creek you could not see us for steam. At Indigo Creek there was a hotel — the Doma Munci it was called, as a sort of compliment to some Italians who were working in a mine close by. The proprietor was an Irishman. Caddy walked straight into the bar and called for two large rums. They were served. I was paralysed. The landlord looked at us with a dubious eye, that quickly became belligerent. A little girl was playing the piano in a back room. 'That's a fine instrument,' said Caddy, ' but it's out of tune.' The face of the publican cleared immediately. ' So it is,' he said. 'Do you know anything of pianos ?' Caddy showed his tuning key, which he always carried with him. ' Come in,' said the publican. We stayed there two days, living on the fat of the land and drinking everything we liked to call for. Caddy confided to the landlord that he was really Signor Caddi from La Scala, in Milan. 1 was in horrible fear that the miners would come in and give us away, because neither of us could speak more than three or four words of Italian. Sure enough a gang of them came around. 'It's all up,' said Signor Caddi, ' we shall have to slip out through the back door.' ' Not yet,' I said, ' Let me try.'

I had noticed that the leader of the gang was a hairy Savoyard with the eye of a Salvator Rosa brigand. I drew him aside, and told him our story. He was delighted. 'I fix-a that,' he said, Then going in and addressing the landlord. 'Very fine musician that-a. Comes from Palermo— he is Si-cil-ian.' The others looked at him, but he cowed them with his eye. Fortunately there was an old fiddle in the house Caddy played on it for them. And what a time we had— a Carnival— a Saturnalia. They danced the dances they used to dance when they amused Horace on his Sabine farm. Slow graceful dances of the Lido, brigandish corroborees of the Abruzzi, mad Neapolitan tarantellas. Not one man of the lot was drunk and they must have consumed a hogshead of wine. ‘You and your mate can stay a week here, if you like,' said the landlord.

The following Saturday was the payday at the mine. Caddy absorbed himself in his business, He took the piano to pieces. It wasn't a piano anyhow — it was a harmonium. But the landlord didn't seem to know the difference. We were regular attendants at meals! Caddy used to come out of the back room now and then with a board stuck full of brass pins in his hand. One of the pieces at the back of the harmonium. He screwed the pins this way and screwed them that way, and whistled reflectively. The landlord and I were sitting on the verandah smoking Doma Munci cigars, and watching the rain. 'Pretty tough job?' said the landlord. 11 Very tough,' replied Caddy, 'but I can manage it,' On the third morning it was necessary to leave. I wanted to get along. The landlord asked us to stay till the end of the week, but I told him it was not possible. / knew. We bored along through the rain, and Caddy said, after we had turned the corner of the road — ' We'll cut along over this track.' ' But why ?' 'Well, when they touch that harmonium it will fall to bits. I don't know anything about harmoniums.'

* * * .

Then we met Chris, the travelling tinker. He had with him as a sort of acolyte a bilious-faced Swede. When jobs were not plentiful he used to kick the Swede, who told me, in gloomy confidence, that he was a lineal descendant of Gustavus Adolphus, the Lion of the North. All the same, he had to carry the soldering tools, and to attend to the fire under the old tin oil-can, when there was a job to do. ‘Blanky Dutchy, anyhow,' Chris used to say when I would remonstrate with him. The blanky Dutchy pitched the tin and the soldering tools into a creek one night, and was away in the morning with the blue blankets of his employer. Absolutely took them from him while he was asleep, and- we were all asleep. You should have heard Chris swear. Never in my life before had I heard such magnificent blasphemy. But Chris was a philosopher., ' I have a house in Wodonga,' he said. ' Both of yees can stay there for a month if ye like.' It was Chris who swopped with me the Crimean shirt for three white shirts. He put one of the latter on. 'My son,' he said to me, 'occupies the house now. Every time I come up this way we have a blanky fight to see who's goin' to own it for the next year.' We camped that evening in a disused wheelwright's shed. Late at night Chris returned with a black eye. 'Bill owns the house,' he said. Bill was the name of his son.

* ***

It was on the other side of Albury when we were on the way to the Piny Ranges, that we came across the Third Sundowner. Far away on the road in front of us, fifty yards or so, was a man , whose very shadow was ragged. The billy-can he carried— battered, black, grimy, grotesque— looked sinful and shameful in the sunlight. 'Better pass him quickly,' said Caddy. We did so, but when we camped beside a creek, and the billy was boiling, and he came up and spoke affably, what could you do ? Of course, we asked him to join us. Noblesse oblige.

He had been a captain in the 17th Lancers. By name, Bourke. He joined us. Then we had to start sundowning in earnest. We broke away from the ordinary track, and came to a place called, as I discovered afterwards, Brungle Creek. 'Foot of white man.' I said, ' has never trodden here before. You're the biggest man, Bourke; go up to the station and fill the bags.'

I should say that Mrs. Middlemore Matthews, the wife of the musician of that name, had given me an air pillow when I was leaving Melbourne. I cut the partitions, and it made an excellent flour bag.

Bourke could always get flour and meat from a station cook. He. had the grand air which does not brook refusal. Besides he looked as if he were able to work should such a dire necessity arise. * * * And now, having told only a third of my story, I must end.

We arrived in Queanbeyan, and I saw the Postmaster. 'Spruhan ? ' he said, turning over his book. ' Yes, now I remember. He was pretty tight. Jumped off the coach from Cooma, sent away a wire, and then went on to Goulburn.'

No gold mine. I got a billet on the local paper, and I had a chance to take a position in a tannery! Might have been a Mayor by now. Too late to worry, however. THREE SUNDOWNERS (

1902, December 20).

The Newsletter: an Australian Paper for Australian People (Sydney, NSW : 1900 - 1919), p. 13. Retrieved March from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article128800045

Charles Wesley Caddy had five children and a wife who were living in a little cottage in Little Brighton street, Petersham while he was gallivanting with Argles and Daley at Manly. He married Elizabeth Jane Hicks in 1871 in Melbourne. A son of a large family of brothers and sisters, he was classically trained in music and offered a very good education. Prior to pursuing a literary career he worked as a school teacher.

MELBOURNE REVIEW for JANUARY.

We have received from the publishers & copy of the " Melbourne Review " for January. The number opens with an anonymous article on political parties in Victoria. The writer, who is said to be a gentleman of great political experience, whose views are entitled to careful consideration, and who is understood to bo Judge Bocaut, ex Premier of South Australia, tells us that he belongs to one of the most conservative of classes.

…

A further article in this line by Mr. C. W. Caddy begins the discussion of the morals of politics, but readers will probably feel that they will have to wait for a further instalment of the subject before they are able to see exactly what Mr. C. W. Caddy is driving at. The MELBOURNE REVIEW for JANUARY. (

1879, January 24).

The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 7. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13428193

“The morals of politics” is the title of an article by C.Wesley Caddy, which puts in lively way some very well-known but unpleasant facts. The moral, so far, is that the people get what they want, and as there is a demand for time-servers they are supplied. MELBOURNE REVIEW. (

1879, January 16).

The Ballarat Star (Vic. : 1865 - 1924), p. 4. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article199347222

Mr. C. W. Caddy, who contributed a paper on the Morals of Politics to the last number of the Melbourne Review, feels somewhat aggrieved at the remarks made in our critical notice of that periodical, to the effect that his paper consists of " an ambitions but futile attempt to imitate Mr. Mallock's New Republic." , In a letter we have received from him he says, "I have: never read or heard of Mr. Mallock, except in a hack number of the Nineteenth Century, where he discusses the question, 'Is Life Worth Living ?' And as I only got hold of that two days ago, and have not yet read ;it through, 1 am unable to say to what , extent my article, written six weeks ago, may be influenced by Mr. Mullock's speculations or style. But I don't think the traces of Mr, Mallock's invention can be very strong. From an abstract of Mr, Mallock's work, given to me by a friend who has read it, I can find no trace of similarity between the Review article and it ; and I have come to the conclusion that the gentleman who wrote the notice for you has either not- read my article," or has not read Mr. Mallock's. If he has read both, perhaps it would not be too much trouble to point out in a line or two at foot in what respects the plans of the two resemble each other so closely as to have led him to say positively that I ape Mr. Mallock." Mr. Caddy is too sensitive. He has not been charged with plagiarism, and there is nothing intentionally offensive in supposing that he had attempted to imitate a writer of eminence. It was something in his style, we presume, or something in his subject which suggested the idea of resemblance between his paper and Mr. Mallock's New Republic. But what of that? Mr. Caddy should deem it no small praise, for Mr. Mallock's New Republic is an uncommonly clever book. AMONGST THE BOOKS. (

1879, February 1).

Leader (Melbourne, Vic. : 1862 - 1918), p. 1 (THE LEADER SUPPLEMENT). Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article198010175

EASTER OMLETTE.

Such is the title of an unpretentious little work, just published by Mr. George Robertson in Victoria, New South Wales, South Australia, and Queensland. If one were inclined to judge a book by its cover he would speak only in favorable terms of this "shilling's worth." The articles are eleven in number three being supplied by Mr. A. P. Martin, who is himself the editor of the "brochure," as also of " Melbourne Review.'' Among the othercontributors are Garnet Walch, Richmond Thatcher, F. R. C. Hopking, Dr. Moloney, and C. W. Caddy. The sketch " My dealings with the Bank of New Holland," is the story of a little history that I am afraid repeats itself daily in these times. Mr. Thatcher's tale betrays that skilful blending of the serious and humorous that he is so well known for. The poetry is far "above the average," and I hope to see Mr. Martin collect another dish of eggs for public approval next year. AN EASTER OMELETTE. (

1879, May 20).

Riverine Herald (Echuca, Vic. : Moama, NSW : 1869 - 1954), p. 3. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article115122796

NEW INSOLVENT.

Charles Wesley Caddy, of North Carlton, teacher. Causes of insolvency--Sickness of self and family, and pressure of creditors. Liabilities, £310 6s. 5d. ; assets, 10s. ; deficiency, £309 16s. 5d. Mr. Halfey, assignee. NEW INSOLVENT. (

1881, February 19).

The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 - 1957), p. 7. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article5972088

HOPE.

Thus Winter spoke, and dug- himself a grave,

Which open stood till Spring with tear-dewed

flowers

Filled in and, tripping through a grove where save

The bird or butterfly anear its bowers

Comes naught, her sister Summer met ;

Who merry, laughing cried, ' Ah, sister, dear,

Upon Death's roses are thy last tears wet,

Come smile on life. See three lives to one bier.

For our loved Autumn comes.' The beauteous three

Enclasping kissed. Oh, Hope, that kiss made thee I

C. Wesley Caddy.

The Broken Hearts. *

Translated from the Italian, of"Giuseppe Venosta"

(1615-1671),

C. Wesley Caddy.

Band.-There is some talk of a band being organized here. Mr. Caddy, bandmaster at Queanbeyan, has been communicated with, and is willing to teach the members at a very moderate charge. The only thing requisite to start the musicians is a few pounds, which could easily be raised by canvassing the town, the whole inhabitants of which would only be too glad to subscribe towards so desirable an object. BUNGENDORE. (

1881, September 1).

Goulburn Herald (NSW : 1881 - 1907), p. 3. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article117442275

BUNGENDORE BAND Mr Caddy, who for the last month used to visit Bungedore two days a week for the purpose of instructing the members, has resigned his position as bandmaster on account of entering a more lucrative business in Queanbeyan..: During his time here the members have, been under his charge they, got on exceedingly well, and its a great pity he could not have been induced to remain for a few months longer. BUNGENDORE. (

1881, October 18).

Goulburn Evening Penny Post (NSW : 1881 - 1940), p. 4. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article102820621

FATAL TRAMWAY ACCIDENT.

A journalist named Charles Wesley Caddy, 40 years of age, residing at 107 Dight-street, Collingwood, was accidentally killed by being run over by a tram yesterday. He was attempting to jump on a tram in motion in Gertrude-street, but slipped, and, falling, was run over by another tram coming in the opposite direction. He was taken to the Melbourne Hospital, but died a few minutes after his admission. The deceased was formerly a state school teacher, but has for some years been connected with newspaper work in this and the other colonies. FATAL TRAMWAY ACCIDENT. (

1888, August 25).

The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 - 1957), p. 12. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article6899276

KILLED BY A TRAM.

Dr. Youl held an inquest on Saturday on the body of Charles Wesley Caddy, who was killed on the tram line in Gertrude-street, Fitzroy, on the previous day. The evidence showed that the deceased was under the influence of liquor and had attempted to get on a car whilst it was going at full speed. He lunged against the body of the car, and was knocked down. He was admitted to the hospital in a state of collapse, and died soon after his admission from fracture of the skull. A verdict of accidentally killed was returned. KILLED BY A TRAM. (

1888, August 27).

The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 - 1957), p. 9. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article6899357

CHARLES WESLEY CADDY.-The good-natured editor of the CUMBERLAND TIMES, thus speaks of poor Caddy, who at one time edited Mr. John Nobbs' CUMBERLAND INDEPENDENT, [an honour (? ) which we also enjoyed some years ago] as the locum tenens of the editor, Mr. Courtney, during that gentleman's absence on a holiday tour : "Poor little Caddy ! Never was a gentler soul enshrined in so fragile a body as thine ; and never did man face grinding penury with a more cheerful heart than thou didst. Smallest and quaintest of wielders of the pen. Peace to thine ashes ! Few were the joys vouchsafed thee in the flesh ; may rest eternal sooth thy wearied spirit." " Amen" we say to such a prayer. LOCAL AND GENERAL (1888, September 8). Windsor and Richmond Gazette (NSW : 1888 - 1954), p. 4. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article72557790

The Bulletin Case.— On Wednesday evening a public meeting was held in the Temperance Hall, Pitt-street, for the purpose of expressing sympathy with Messrs. Haynes and Archibald on their incarceration in Darlinghurst gaol for non-payment of costs in the late Clontarf libel action case. The hall was crowded, and the Mayor of Sydney (Mr. John Harris) presided.

On the platform were several members of Parliament and other gentlemen. Resolutions were agreed to unanimously expressing sympathy with Messrs. Haynes and Archibald, and deciding to take stops for their release; expressing the opinion that the law of libel as it affects the press of the colony should be amended ; and forming a committee for giving effect to the resolutions. The proceedings throughout were marked by a good deal of enthusiasm, andat the close of the meeting about £100 was collected in the room. No title (

1882, March 25).

Freeman's Journal (Sydney, NSW : 1850 - 1932), p. 10. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article111318206

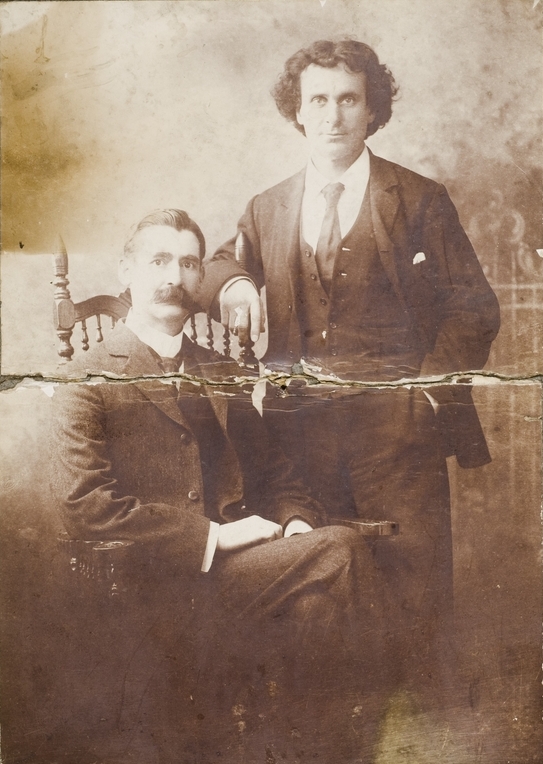

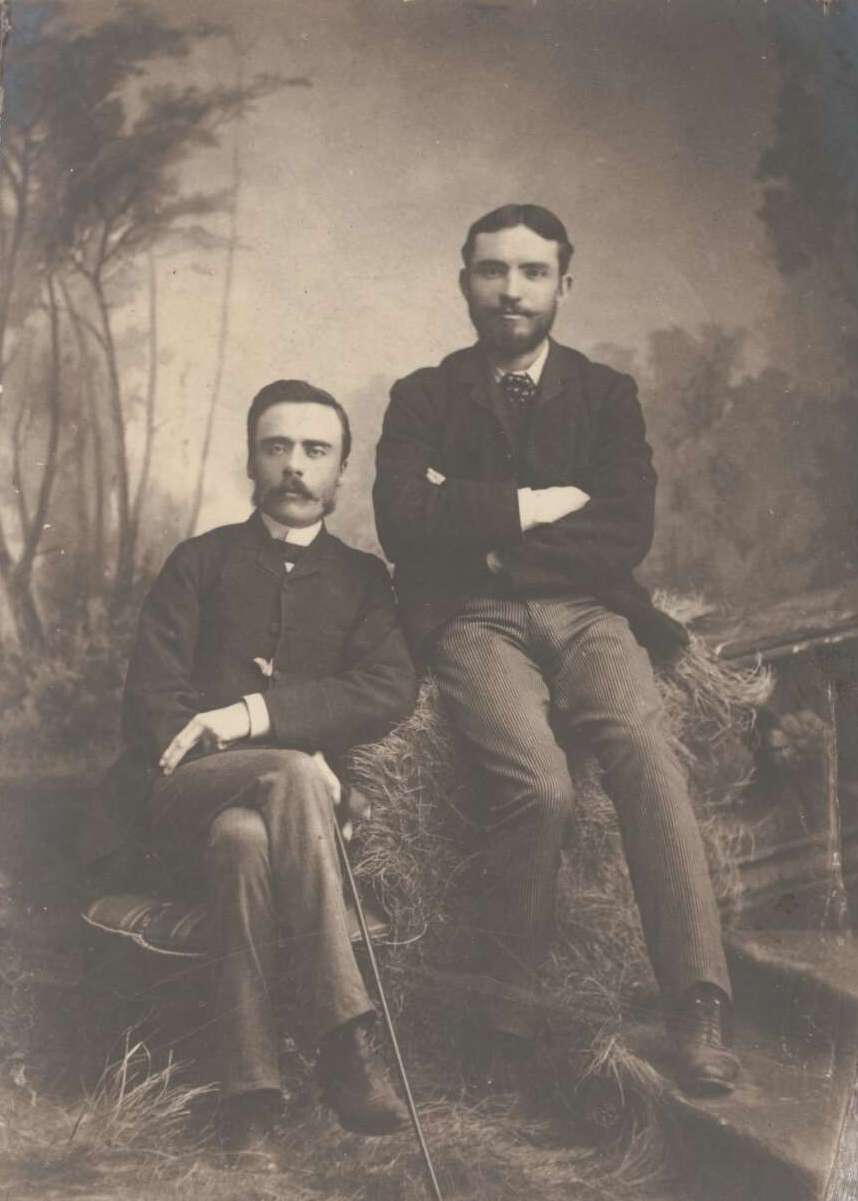

John Feltham Archibald and John Haynes, journalists of The Bulletin, in Darlinghurst Gaol, March 1882 / unknown photographer. Image No.: a4157058, courtesy State Library of New South Wales

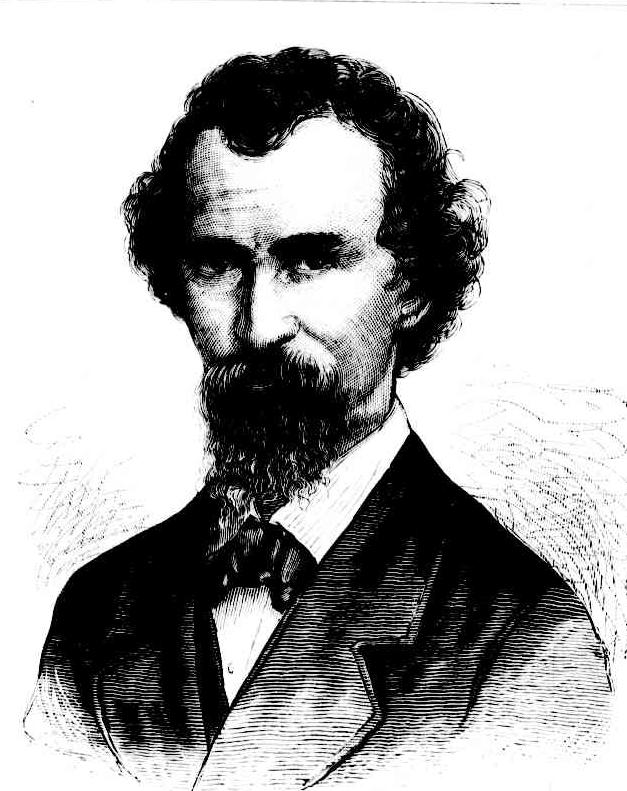

Funeral of the late Henry Kendall

The funeral of the late Mr. Henry Clarence Kendall, took place yesterday, the scene of the interment being the Waverley Cemetery. The ceremony was witnessed by some few of the personal friends of the deceased, but the attendance was by no means so large as might have been expected upon such an occasion. The funeral procession started from the residence of Mr. William Fagan, 137, Bourke-street, and prior to doing so the friends of the deceased availed themselves of the opportunity of looking for the last time upon the dead face before the body was closed to the gaze of man for ever. The features were calm and peaceful, and reposed amid a bed of deep rich moss, feathery ferns, and wax-like flowers — typical of those beauties of nature which, in his life, deceased had loved so well. The poet's grave is situated on a sheltered nook of that portion of the cemetery which commands a view of the vast Pacific, and is upon a spot on which the deceased had often communed with nature, and given flight to the poesy of his soul. The burial service was read by the Rev. Mr. Mitchell, of Waverley. At the close of this portion of the ceremony, and the words, "earth to earth," were being intoned, an unknown lady who seemed to be a chance visitor to the spot stepped forward and showered into the grave and upon the coffin a profusion of the lovely flowers with which the place abounds. So ended the funeral ceremony of Australia's most gifted poet.

Mr. Alfred Allen writes : — According to his own dying request the prince of Australian poets was buried in the Waverley Cemetery yesterday. The last act connected with a remarkable life was performed in the presence of a small assemblage composed of relatives and admirers of the wonderful genius who has so lately left the ' bivouac of life ' for the poetry of the unknown world. Such an occasion should have called forth the sorrow and sympathy of the nation, for the loss is a national one. In day's to come it will be a matter for regret that on August 3, 1882, when the last remains of Henry Kendall were being committed to the tomb, only 20 citizens could be found to stand by the open grave, while dust was cast upon the coffin that contained the mortal part of the most gifted poet who ever graced the pages of southern literature.

Those 20 mourners deserve mention, and I trust you will let these names go forth. Sheridan Moore. D. O'Connor, Harry Wood, H. Croft, E. Ward, P. O'Connor, H. Evans, T. H. Rutter, S. L. Rutter, J. Henry, W. Kendall, B. Kendall, J. Kendall, E. Fagan, J. D. Fitzgerald, J. Bruce, P. J. Holdsworth, D. Fagan, J. Butler, and the writer. Poor Kendall, with all thy faults, in ages to come the sweet strains of thy measured lines shall become the songs of a great nation. Thou hast left behind a fadeless name, imperishable glory will hover about thy memory. Thy grave by the shore where all that is left of thee now rests shall speak to the children of the fair Australias in a language the immortal great alone can utter. Funeral of the Late Henry Kendall. (

1882, August 4).

Evening News (Sydney, NSW : 1869 - 1931), p. 3. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article108209275

This just after the death and funeral of Henry Kendall:

In addition to the gentlemen whose names were mentioned by Mr. Alfred Allen in Friday's Evening News as being in attendance at the funeral of the late Henry Kendall, the following also followed the cortege :— Edwin Caddy, B. Thatcher, O. Wesley Caddy, Victor J. Daley, and Mr. P. Hogan. BREVITIES. (

1882, August 7).

Evening News (Sydney, NSW : 1869 - 1931), p. 3. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article108208557

Death of Henry Kendall

All lovers of literature, more especially in the realms of poetry, will regret to hear of the death of the well known Australian poet, Mr Henry Clarence Kendall, who expired last evening at the residence of his brother-in-law. Mr. Fagan, Bourke-street, Surry Hills — the cause of death being consumption. Mr. Kendall had long been ailing, and it was seen by his friends for some time past that he was gradually sinking, and must soon seek final rest in that undiscovered bourne from whence no traveller returns. For years past his name has been associated with the foremost men of letters in Australia, standing at the very head of those whose particular inclination led them to the cultivation of the art of poetry. Mr. Kendall was undoubtedly the poet laureate of Australia, and his early decease at the age of 40, leaves a void which will be very hard indeed to fill. Like many other men of genius (among whom may be mentioned the great Deniehy, with whom he can be fairly associated in the field of poetry and literature, being at the head of one as Deniehy was of the other), he was a man of singular impressions and temperament, and like him found the world was not always too kind to him. This led him into a vein of gloom which was unfortunately accompanied with, that reckless disregard for his health which no doubt had in the long run much to do with the undermining of his constitution.

A twin brother (the other having died some years ago), he was born at Ulladulla, New South Wales, in 1842, and received a private education during the earlier years of his life. When only 18 years of age, he commenced his career as a writer for the Press, contributing to the columns of the 'Empire' and the "Herald" for about 10 years. In 1862, he published his first complete work "Poems and Songs" but he evidently thought little of it, as he suppressed it three years later, considering it was altogether too crude to make him any reputation. During the time mentioned, he also supplied the Town and Country Journal with many contributions, both in poetry and prose, as well as writing for the "Freeman's Journal" and the "Sydney Punch." In 1863, he obtained an appointment in the Lands Department, and was afterwards transferred to the Colonial Secretary’s office, where he remained until 1869. But the trammels of the desk were too irksome to him,, and he threw up the appointment, and proceeded to Melbourne, where he became a contributor to the "Australasian" and other leading journals, including the "Argus," the 'Telegraph," "Punch," the "Colonial Monthly," and "Humbug and Touchstone." Among other good work done in Melbourne was a prize poem on an Australian subject. He entered eagerly into the competition and won the prize, his poem being considered by the judges appointed far and away the best. Later on, in conjunction with Charles Edward Horsley, he composed the cantata for the opening of the Melbourne Town Hall. From adverse circumstances, against which he had to contend alone, this period of his life, in which his one weakness came to the front, to the injury of his health and strength, he quitted Melbourne and returned to this colony, and went almost immediately to Brisbane Water, where he was employed until last year, when he was appointed inspector of forests, a situation which it was generally thought he would be able to fill with efficiency, his well-known love of the woods, forests, and silent places, in which he had for years been wont to commune with nature, and in which he had gained much practical experience, having thoroughly qualified him for the proper carrying out of the duties attached to the office. His health, however, was undermined and a few weeks ago it broke down completely. He lingered on until last evening, when he died as above. That Mr. Kendall was a true poet no one can deny. His verses had the golden ring and the bright imagery so essential to the completeness of this class of literature. A lover of his native land, with perhaps one exception (Adam Lindsay Gordon), there is no writer whose works have treated so much of life relating to this land. Living often apart in the depths of the forests in his lone Australian home, he was conver-sant, it need scarcely be said, with the works of all the English bards, and from them he accepted nothing. His style was purely his own. There was a glow, a colour, and a richness about his works that have never been surpassed by any poet in any country, or at any time ; and Kendall's early death is a loss to the world of Australia which all must deeply deplore. His bright genius thus early nipped in the bud shows another example of misdirected character. His power increased with every work he published, and but for the destroying influence by which he was enveloped he would have doubtless risen to fame as one of the greatest of living poets. His "Songs from the Mountains" was a noble work, and it would doubtless have been surpassed but for the reasons mentioned. His second work "Leaves from Australian Forests" was a great improvement on his first, and each succeeding book contained beauties still more rare. Not only has his poetry received the highest commendation in his country, but English literary journals of the highest class have noticed it with great favour. The "London Athenaeum"' spoke of his poems at length and in the most glowing terms. Two of his poems — "The Song of the Cattle Hunters,'' and "The Ghost Glen" — were published in extenso and the critic said : — If Mr. Kendall continues to exert his faculty as successfully as he has done in these two pieces, England as well as Australia will gladly recognise his place as a singer. He has both disadvantages and advantages in his distant sphere, but the latter preponderate. He occupies virgin soil, stands in the midst of a society whose characteristics have never yet been mirrored in song; while English writers are throwing up their pens yearly because they can assimilate nothing new. Let him seek in the great life around him those human forms of humour, pathos, and beauty which, touched by the gifted hand, cannot fail to win the heart of the public; and let him use his local colouring, a precious treasure to illustrate truths which are universal. It is impossible, of course, to say how he will succeed in the profounder labour of dramatic insight, such faculty as he shows in the poem before us being distinctively a lyrical faculty ; but that he has gifts there can be no question ; and his communication to us is so modest and so sensible that we are assured he will put these gifts to the best use, leave his imitative efforts behind, and strike out in the path which he is most suited to explore. Mr. W. B. Dalley, in writing of Mr. Kendall's last work, fully endorses this opinion, and speaks most highly of the creation of that brain which, now lies still in death. The work of his later years shows traces of the sorrows of his life and is tinged with the gloom which was in part the nature of the man ; while a part was doubtless brought about by his own weakness of character. It was only in the dedication to his last collection of poems that he wrote the following words, which are the closing cries of a life that seemed ready to give up its struggle with the world and its own inherent gloom:

"These are the broken words

Of blind occasions when the world has come

Between me and my dream. No song is here

Of mighty compass; for my singing robes

I've worn in stolen moments.

All my days Have been the days of a laborious life ;

And ever on my struggling soul has burned

Daley was profoundly affected by Kendall, as were all those he had as boon companions then. In a later article he puzzles or laments over why so few followed Kendall to his final resting place while so many follow those of means or political renown that may not have given what poets gave or inspired. He wrote this tribute days afterwards:

LOVE-LAUREL.

In Memory of Henry Kendall.

Ah! that God once would touch my lips with

song

To pierce, as prayer does heav'n, earth’s breast of

iron,

So that with sweet mouth I might sing to thee

O sweet dead singer buried by the sea

A song, to woo thee as a wooing siren

Out of that silent sleep which, seals too long

Thy mouth of melody.

For, if live lips might speak awhile to dead,

Or any speech could reach the dead world under

This world of ours, song surely: should awake

Thee who] didst dwell in. shadow for song's

sake.

Alas ! thou canst not bear the voice of thunder,

Nor low dirge over thy low-lying head

The winds of morning make.

Down through the clay there comes no sound

of these,

Down in the grave there is no sign of Summer

Nor any knowledge of the soft-eyed Spring ;

But Death sits there, with outspread ebon wing,

Closing with dust the mouth of each new-comer

' To that mute land where never sound of [seas

Is heard, and no .birds sing.

Now thou hast found the end of all thy days

Hast thou found any heart a vigil keeping

For thee among the dead — some heart that

heard

Thy singing when thou wert a brown sweet bird

Gray eons gone, in some old forest sleeping

Beneath the seas long since ? In Death's dim

ways

Has thy heart any word ?

For surely those in whom tho' deathless spark

Of song- is Kindled, sang from the beginning

If life were always ? But the old desires —

Do they exist when sad-eyed Hope expires ?

How live the dead ? what crowns have they for

winning?

Hare they to- warm them in the dreamless dark

For sun earth's central fires ?

Are the dead dead indeed whom we call dead ?

Has God no- life but this of ours for giving ? —

When that they took thee by each- well-known

place,

Stark in thy coffin with a bold white face,

What thought, O brother, hadst thou of the

living?

What of the sun that round thee glory shed?

What of the fair day's grace ?

Is thy new life made up of memories

Or dreams that lull the dead, bright visions

bringing

Of spring above ? Are thy days short or long ?

? Thou who wert master of our singing throng

Mayhap in death thou hast not lost thy singing

But chauntest unheard, by the moaning seas,

A solitary song.

The chance spade burns sip skulls. God help

the dead,

And thee whose singing days are all past over — ,

Thee whom the gold-haired Spring shall seek

in vain,

When at the glad year's doors she stands again

Remembering the song-garlands thou hast wove

her

In years gone by. But all these years have

fled

. With all their joy and pain.'

And thou hast followed them by hollow ways,

To Death's dark land where hushed is Life's long

quarrel ;

A land unlit by sun, or moon, or star, e

Shining from the fair heaven faint and far

On sombre cypress trees, and lordly laurel.

There thou hast found sweet end for bitter

days

Down where the dead men are.

My soul laughed out to hear my heart speak so

And sprang forth skyward, as an eagle, hoping

To look upon thy soul with living eyes,

Until it came to where all known life dies,

And dead suns darkly for a grave are groping,

Through cycles of immeasurable woe,

Stone-blind in the blind skies.

The stars walk shudd'ring on that awful verge

From which my soul shot, as a daring swimmer

Through dim green depths, and sought for

God and thee ;

But God dwells where nor stars nor suns there

be, .

Deep in the heart of space, whence unto Him are

A thousand systems as a fringe of surge

On His great starless sea.

And thou wert not. So that with weary plumes

My soul through the great void its way came

winging

To earth again. ' What hope for him who sings

‘Is there,' it sighed, ' Death ends all sweetest

things.'

When lo ! there came a swell of mighty singing

Flooding all space, and swift athwart the

glooms

A flask of sudden wings.

Let be, lie still, thy songs and dreams are done.

Down where thou sleepest in earth's secret bosom

There is no sorrow and no joy for thee,

Who canst not see what stars at eve there be,

Nor evermore at morn the green dawn blossom

Into the golden king-flower of the sun

Across the golden sea

But haply there shall come in days to be

One who shall hear his own heart beating faster,

Plucking a rose sprung from thy heart beneath,

And from his soul as a sword from its sheath

Song shall leap forth where now, O silent master,

On thy lone grave beside the sounding sea,

. I lay this laurel-wreath .

VICTOR J. DALEY.

The Late Henry C. Kendall.

In another page will be found a literary memoir of the late Mr. Kendall, from the well-known pen of ' W. B. D.' The following were the principal facts of his life : — Mr. Kendall, who was 40 years old at the time of his death, was born at Ulladulla. New South

Wales. When only 18 years of age he commenced his career as a contributor to the Sydney press, and two years later published his first book, ' Poems and Songs.' His later publications were ' Leaves from an Australian Forest,' in 1869, and ' Songs from the Mountains,' in 1881. In . 1863 he held an office in the Lands Department, and subsequently was transferred to the Colonial Secretary's Office, where he remained until 1868, when he resigned and went to Victoria, where he resided for some time and became a frequent contributor to the Melbourne press. He subsequently returned to this colony, and accepted a situation at Brisbane Water, where he resided till 1881, when he was appointed Inspector of Forests. He was the composer of the cantata for the opening of the Melbourne Town Hall, and the cantata for the opening of the Sydney International Exhibition, and the prize poem in commemoration of the last mentioned event. Latterly his health broke down completely, and after a few weeks' severe illness he died of phthisis on August 1, at Bourke-street, Surry Hills. The following' verses appeared in the Echo on the 2nd instant : — Only a poor frail singer dead, A sad, strange spirit gone, shall sigh be sighed, or tear be shed, That he is God-ward drawn ? His was no bird song carolled out, No love song dear and high ; He never raised one joyous shout Beneath a summers sky. He sang of sorrow and regret, Of passion and despair ; As one who never could forget, A dawn that promised fair ; As one on whom a hand was laid, To whom a harp was given, And in whose ear an angel said, Sing out the songs of heaven ! As one on. whom a shadow fell Before the promised day, And from whose hand a fiend of hell, Snatched harp and song away ; As one who through a weary life Toiled on in bitter pain, And spent himself in ceaseless strife To grasp his song again. Strange visions filled him with affright, And oft with shuddering dread, He felt the awful robes of light Go trailing overhead. He struggled, as a brave man should, The cankering curse to kill ; But strong, cruel, foes against him stood. He failed, as weak men will. At times a high power touched his tongue, And while not all forlorn, He sang as no man else has sung Since Austral song was born. We knew his strength and weakness both, And now that both have past, May pray, God rest him ! nothing lotL, That he has peace at last. Francis Myers.

T

THE LATE HENRY CLARENCE KENDALL. From a Photograph by Newman, of Oxford-Street.

A meeting of the members of the Athenaeum Club was held at the rooms, Castlereagh-street, on Monday afternoon, for the members for the purpose of expressing their regret for the loss the Australian literary world has sustained by the death of the poet Henry Kendall. There was a large attendance, ana Mr. S. Cook was voted into the chair. Some discussion took place as to what action the meeting should take in the matter, and various suggestions were thrown out. An opinion was expressed that the general public ought to undertake the duty of providing for Kendall's widow and family, and that the club should do something towards perpetuating his memory, either by a memorial stone or by establishing a medal or a scholarship at the Sydney University in his name as a prize for the best English verse. As the meeting was purely a preliminary one, it was eventually decided to a general meeting of the members, to be held at 5 o'clock on Wednesday afternoon, and in the meantime a sub-committee was appointed to collect such information as may assist the general meeting _ in deciding upon some definite scheme. A preliminary meeting of gentlemen interested in preserving the memory of the late Henry Kendall and the welfare of his family, was held at the Bulletin Hotel on Monday afternoon, when the following resolution was passed, ' I viz. : — ' That a committee, consisting of Messrs. Thatcher , Holdsworth, Caddy, Dowling, Donahue, P. O'Connor, Godbolt, V. J. Daley, T.J. Cowper, H.S. Chauncey be formed to co-operate with any committee which may be appointed by the members of the Athenaeum Club, to take into consideration what is best to be done to aid the family of the late Henry Kendall, and perpetuate his memory.' Mr. V. J. Daley accepted the position of honorary secretary. The Late Henry C. Kendall. (

1882, August 12).

The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1871 - 1912), p. 249. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article161923484

"Patience" is a howling success, and the siring of wool kings and dry goods princes' carriages extends down Castlereagh-street, long past Dick Thatcher's Bulletin Hotel door every night. The " fashion " of Sydney went to see how their congeners of England comport themselves, and we shall probably have a colonial aesthetic school, who will feed on the odour of faint lilies, writhe in amaranthine asphodels, and indulge in the other ridiculous phantasies that come out of burlesquing art adoration, Ono lady has occupied a box each night, and feasted upon the certainly unaesthetic limbs of the burly baritone, and even gone so fur as to express marked disapprobation of a female member of the company wooing him in pursuance of the action of the piece. Under the circumstances the abolition of cucking stools seems a mistake. The success of the opera is deserved, for we have never seen such mounting, or been treated so munificently in the matter of dresses, music and appointments. Some of the ‘supes’stand up in twenty pounds worth of togs apiece….LETTERS TO THE OLD MAN. (

1881, December 15).

Wagga Wagga Advertiser (NSW : 1875 - 1910), p. 2. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article101815433

Moore was permitted to transfer his license for Wangenheim's Hotel to Richmond Thatcher. The latter was granted a billiard license, and also permitted to change his sign to the Bulletin Hotel. WATER POLICE COURT (

1881, October 22).

The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 7. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article28382790

And, in the city, the men of lusty intellect For example, Gus Wangenheim, of Sydney, famous for his beer, his lordly frame, his humours, his deep and unctuous voice, his skill in portraits and caricature", and the Bulletin Hotel's Dick Thatcher, who had played half the stages of Australia, who managed Mrs Siddons, who collected sea-shells and knew every beach from Tahiti to Geraldton, who founded newspapers and edited the "Newcastle Morning Herald", and the… " BOOKS OF THE WEEK (1953, January 10). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 8. Retrieved, fromhttp://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article18353139 THE NEW BOHEMIA.

By Victor J. Daley.