December 1 - 7, 2013: Issue 139

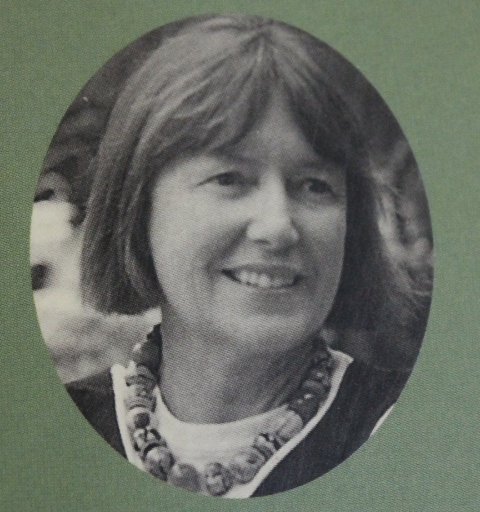

Jan Roberts

It’s no secret that we here are huge History fans and spend months, and in some cases, years tracking down all the threads we can to try and encapsulate a few of the right ‘notes’ in the right sequence to deliver up another page each week on all the many historical aspects of Pittwater. One lady whose footsteps we stumble in and whose works we have long admired and read with great pleasure is Jan Roberts, instigator of Ruskin Rowe Press. We are not alone in referring to her books – many an Australian writer lists her works as a Reference in their own works on Historical aspects of Australia and Australians.

It’s no secret that we here are huge History fans and spend months, and in some cases, years tracking down all the threads we can to try and encapsulate a few of the right ‘notes’ in the right sequence to deliver up another page each week on all the many historical aspects of Pittwater. One lady whose footsteps we stumble in and whose works we have long admired and read with great pleasure is Jan Roberts, instigator of Ruskin Rowe Press. We are not alone in referring to her books – many an Australian writer lists her works as a Reference in their own works on Historical aspects of Australia and Australians.

Not only is Jan meticulous and passionate about all she shares through her many publications, she is also an inspiration to women who pursue excellence in all areas of life; professional and family. This week it is our very great privilege to open a month of inspirational Pittwater ladies with one of the best: Dr. Jan Roberts.

Where were you born?

I was born in Waverly Hospital during the war (WWII) so I was a war baby, in 1941. shortly after I was born my father left to fight in the Air Force and so I grew up without a father until 1945.

Which unit was he in?

Because he was born in England and our family had actually been living in New Guinea and had been forced out of there due to the war, he joined up early and was sent over to fight with the RAF (Royal Air Force – England)230 Sqd.. He was a Rear-Gunner.

I was four years old when he came back. He was sent to Wangi where he had to decommission the Sunderland Flying Boat Squad. So my first memories of my father are at Lake Macquarie, at Wangi.

You lived with your maternal grandparents at Pennant Hills during the war- can you recall much of that time?

Yes – I can recall that when planes went over we were very frightened that it was a Japanese invasion because of what had happened in New Guinea. My mother was very nervous about the Japanese coming south and interestingly I was only reading yesterday through some of my New Guinea connections, one of the journals that I subscribe to, was giving the story of the Australian soldiers who went into the caves at the back of Rabaul just after the war ended and found the Japanese soldiers had left detailed maps of every large Australian city.

We’ve always been puzzled about whether the Japanese intending coming to Australia. Historians have long been divided on that questions, and now I’m thinking this is the missing evidence. We knew they were intending to go to the Pacific islands and now clearly they were using New Guinea as the jumping off base for invading Australia, and not just Northern Australia but for the whole of the continent. The article is convincing and well written. The writer now lives in England and has asked for correspondence.

What was the landscape of Pennant Hills like then?

Very rural. Small orchards, wonderful bush, no division by major roads – a quiet and gentle place for us to spend the war years. The only man was my grandfather who was by then quite disengaged from children, so it was really just my young aunts, my mother and my brother Peter and me.

We had a happy wartime there, except for my mother’s nightmares which I only found out about later, about having to put me and my brother in a pram and try to get to Central Australia somehow to get away from the Japanese bombs. So there was an underlying fear all the time.

You moved to Avalon post WWII – this would have been the first time you met your father and spent time in a coastal area?

I talk about this in Remembering Avalon. During the war my mother came down with a friend to visit her friend in Elouera Road and saw her first koala in a tree and decided that she would never ever leave Avalon…and she never did. She lived where my husband and I now live for fifty years, until she was 93 and unfortunately had to go to a nursing home. Just before she died she came back to Avalon for one last family lunch. Avalon was deeply embedded in her consciousness. She’d moved a lot, particularly during the Depression years, but once she came to Avalon that was it – she was never going to live anywhere else.

She had a sense of ‘home’ here?

Yes, immediately. It was the beauty of Avalon.

Did you get a similar sense?

Definitely. We lived in Avalon all these years, but there was a gap for me when I left to go to university. I thought I’d never come back to Avalon because it seemed too far away. We did move back though, my husband and I and Katherine, into Ruskin Rowe, in 1990.

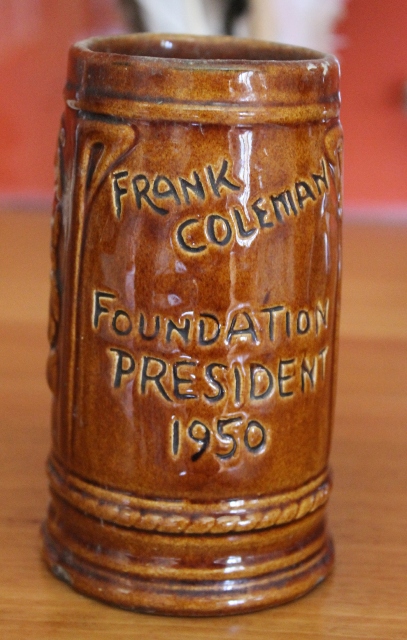

You bought 28 Ruskin Rowe – isn’t that the Frank Clune home?

Yes, it was the Frank Clune house. Frank Clune had a strong Avalon connection, with his wife Thelma and two sons – one of whom had the Clune Galleries in Potts Point, which was a well known gallery he and his mother ran. The Clune art connection was strong in Avalon and Ruskin Rowe in the 1950s and 1960s.

Did you ever meet him?

Did you ever meet him?

No but my parents knew him. We have a wonderful Frank Clune book ‘Ben Hall the Bushranger’ and Frank Clune has signed it to my father Frank, “From one old bushranger to another”.

They used to meet at the old Avalon RSL, which my father was the first President of. My brother and his friends, all the men and boys, helped build this little ‘man shed’ so that after the war the men could go somewhere and talk about their war (experiences) over a beer or two. Frank Clune was part of that.

Did you notice your father showing signs of having been affected by the war?

Yes, he was definitely affected but I think like many families, and many war babies, you don’t put it together until much later. One of my aunts said he was a different person when he came back. Most of his squadron didn’t make it back and being a Rear Gunner was probably one of the most dangerous jobs in the war because that was the one they tried to get rid of. He had many narrow escapes and was so traumatised that - and I didn’t find this out until quite recently when one of my uncles told me - when they did return to Australia, and landed in Western Australia, by plane – a very long air hop, we have a certificate on that - he refused to get on another plane. He thought he might be testing his luck too much and insisted on catching the train back. This meant that he was a little bit later then he as meant to be but at least he felt that he would make it back to Sydney!

Now…growing up in Avalon…What were the best things to do – could you give me a rundown of a typical weekend during winter and then summer?

We didn’t distinguish that much between summer and winter and seasons, but I guess it was there. A typical weekend would be one of total freedom. Maybe I had to go to ballet for a short while but once my parents saw me at the annual concert at the age of about eight and realised I was out of step and totally disinterested that was the end of ballet! Art and craft and Girl Guides were my occasional ‘activities’ but otherwise on a weekend, we would have almost total freedom. We’d ride our bikes all day, visit friends, climb trees, build cubbies in the bush, the gangs would fight; there were little boy and girl gangs would have fights as one cubby was destroyed ...things like that.

We loved to explore St Michael’s cave and the sandhills were good fun whether it was summer or winter. To us the only real difference was if the water temperature was be too cold we wouldn’t go in. But for at least eight months of the year we spent most of our time in the water.

If you look back at that time from now, do you get a sense of some atmosphere of Avalon that is different from now?

Well, of course, it’s much larger now but I like the coffee culture, I like a lot of the modernity. Once the cinema was built that provided us with tremendous entertainment and I do regret that that has changed as it was such a central focal point for everyone. It was also somewhere where artists could sell their work. We’d got to the pictures, have coffee and cakes and meet our friends- we all thought it was the centre.

What about the Barefoot Boulevard shopping centre when that was built?

Yes, that was part of our lives with the art classes and exhibitions and it was very successful. Everyone then, and I think this has continued, had a strong sense of conservation and preservation and keeping Avalon as untainted as we could from developments like hotels. There were two strong moves to have a hotel built, one in the Barefoot Boulevard. Another was an attempt to subdivide the golf course. Both of these were hugely fought by residents. So I think even though Avalon was small then it had a strong sense of self-preservation to keep the character and identity of the area. And it wasn’t only the Avalon shopping centre. We owe a debt to the bush lovers who gave us Angophora Reserve and Hudson Park, where you can walk amongst nature as it was, knowing that it has not been interfered with.

Where did you go to University?

There was only one university then in Sydney. You could go to New England and some of the locals did go there, but I went to Sydney University. After looking at the bright young people who had attempted to commute I decided I needed to stay further in so I took a Teacher’s College Scholarship which gave me an away from home allowance. We were a fortunate generation. I’ve been able to get all my university education for nothing. I’m grateful to the policy makers as my family didn’t have the wherewithal to allow me to take up even the Commonwealth Scholarship, as it was then. I would have had to live at home and that would have meant about six hours commuting a day in those days, on top of studying. I knew I would have had to work hard just to pass the exams. It was difficult then – if you didn’t pass three subjects each year that was it, you couldn’t continue.

Right: Jan's First formal, Manly Golf Club, 1955, courtesy Remembering Avalon(2011), edited by Jan Roberts, Ruskin Rowe Press.

What degree did you get and where did you go?

BA and Dip Ed for teaching. The Department of Education always sent young teachers west. I went to Penrith High for my first teaching job. I set up house in Strathfield with a group of friends from university – all young teachers. This was 1962. I was just a few years older than some of the students. I loved it. My next year I was at Rooty Hill. We helped set up the High School there. Lorraine Rawlings would remember that. She is an Avalon resident who was there as well.

Where did you meet Ken?

On Bilgola Beach. I was eighteen or nineteen. We met through mutual university friends. He, for a North Shore boy, was an extremely good surfer and I was impressed by that. I know that may seem shallow…

We’re talking surf bathing here?

Yes – we didn’t have surfboards then. They were too big for me. We’re talking body surfing. That was what we all loved to do then, and to be out-surfed by this smooth fellow. I was impressed but angry. (laughs).

How long were you ‘going out’ before you married?

Quite a long time. He went to Adelaide to work. It was several years before we were able to marry and then we went almost straight away to live in England. We married in 1963 – we’re having our 50th wedding anniversary next month. We went to live in England in 1964.

Where did you go in England?

Sheffield. He was a Trainee for Unilever and I taught English in a girls Grammar School.

What was that like?

Marvellous. I would walk through fields with badgers! We were living on the edge of the Derbyshire Moors and the edge of Sheffield. People have described Sheffield as ‘an ugly picture in a beautiful frame’ and that’s how it was, framed by magnificent Yorkshire and Derbyshire countryside. Sheffield was very industrial then, with many World War Two bombsites that hadn’t been repaired. The girls Grammar School was a great institution, wonderful teaching. The girls were from very diverse backgrounds, and being a Grammar School, we were all committed to learning.

How long were you in England?

We were there three years. We came back and went to Melbourne. Our first child was born in Sheffield, the second in Melbourne and we came back to live in Sydney in 1970 and had Katherine. We decided we’d never leave Sydney again.

You must be very proud of Katherine – curator at Manly Art Gallery – she works very hard, has ensured many successful exhibitions are shown there?

She works hard and juggles her many roles very well. Our eldest son Paul runs his own charity business called ‘Pareto’. Pareto (http://paretofundraising.com/)takes its name from an Italian economist who believed every human society whether feudal, communist or capitalist, has an 80/20 system where 20% of the population end up with 80% of the wealth. He’s a bit of a Robin Hood person who trained in Government, Economics and Law at Sydney University. He decided he might try and redress the balance a little and help through Pareto to prove this equation wrong. He and his friends started this business up and it has over 100 staff and helps people all over the world now. It runs on a different system from most charities.

Our second son Mike ( I wouldn’t say all this except you asked) works for Emirates as a captain of the A380 and lives with his family in Dubai.

Did he meet his grandfather?

No, none of them met their grandfathers but they all knew both their grandmothers well. Norma Roberts and my mother Gwen Coleman were very much part of our family and a strong part of the reason we decided to return to Australia and then Sydney. They were both widowed while we were in England.

The books you have published – many of these have a strong focus on women and their voices and ensuring there’s a record of these, particularly of Maybanke Anderson. Being aware of the kind of social atmosphere you grew up in, was it important to you for women to have a voice?

Definitely. I really don’t know where it comes from, whether it’s my subconscious or something else. My mother was never an activist. She was a great reader and a highly intelligent woman but women’s rights and women’s voices were never really significant to her. Maybe it was from the Methodism that runs through our family – my grandfather was a Methodist minister.

Methodism was and is strong on human rights, but for women’s rights, I’m not sure. When the second stage of the women’s movement came in the early 1970s it was like a revelation to me as it was to many women of my generation. Suddenly History became less boring. We knew there was another half of the human race but we had rarely heard their voices.

I became part of a movement really, to try to restore women’s voices into history and to give some equilibrium to the whole record of what the generations that follow us will have. For example, if history is only kings when three of the greatest English rulers were queens, then it is a false record, and history with only kings and men became boring at school and university. Australian History in the 1950s was all male. Perhaps that is why many women feel sad about recent events in our history, after we had such hope for Julia Gillard.

I can remember when young being told ‘little girls are seen and not heard’ – did you hear this too?

Yes. In my family I did fight for equality, mostly on the size of food portions, I’m embarrassed to relate! One of my cliché comments when I was young was “it’s not fair!”

Where it came from I have no idea, because my mother was a very gentle person.

If there was something you could communicate to our younger generation of women, those now learning and about to embark into the world with their own aspirations and not wanting to live under the supposed ‘glass ceiling’ – what would you say?

To pursue their dreams. And definitely NOT get trapped in the beauty game. This is the big problem, and I see it already with my granddaughter who is only twelve going to a birthday party where a beautician turned up to give the children facials and manicures!

For twelve year olds??!

Yes….This whole artificial world is such a trap. The beauty game and addictive technology are to me the biggest challenges, especially for young women. The other big challenge for women is to respect and love other women and girls. Be kind to each other. We’ve seen so many examples where girls and women can be so cruel to each other. Why this is is very hard to fathom.

The other focus of your works has been on buildings and architecture – one has been on the Astor and another is Avalon Landscape and Harmony – you are clearly attracted to structures and landscape and the history inherent in those. Where does that stem from?

I think it’s within all of us to be interested in buildings. Everyone can be an instant expert, like education - everyone thinks they know a lot about education and architecture.

With buildings, I think it’s the part of our aesthetics which needs developing. I cringe with what we’ve done to our beautiful coastline. That was the driving force in Avalon Landscape and Harmony , being ashamed of how we have destroyed most of our unique eastern coast of Australia. It is really quite wicked, the ugliness of most buildings.

That’s why I was attracted to Frank Lloyd Wright and the Griffins and their aesthetics of organic architecture; using natural materials and trying to live gently within the landscape and not dominate it. And to try and put in appropriate gardens – these huge European hedges and European trees really have very little part in how I see the Australian landscape should be lived in. So, yes, that book arose out of a very deep part of me and a deep love of buildings; old buildings, stone buildings, the use of timber and glass, and living in harmony with nature.

What then is your ideal Pittwater Summer house?

My ideal Summer House would be an Alexander Stewart Jolly house. We are fortunate to have three in very good condition still in the Avalon area so I would unhesitatingly say ‘Loggan Rock’, ‘Careel House’ and what used to be called ‘The Gem’, now ‘Hy Brasil’ in Chisholm Avenue.

Why history ? Why is it important to record our stories in our own voices?

There is a big difference between the human voice talking and reading text off a page. There’s an immediacy with the spoken voice. Some writers can achieve that. Catcher in the Rye is a famous example. Although the human voice makes errors, and you have to transcribe carefully, it can be powerful while being plain. You also remember things to, are prompted if you have a sympathetic person listening or who is doing the recording to remember things you haven’t thought about for years.

There is a big difference between the human voice talking and reading text off a page. There’s an immediacy with the spoken voice. Some writers can achieve that. Catcher in the Rye is a famous example. Although the human voice makes errors, and you have to transcribe carefully, it can be powerful while being plain. You also remember things to, are prompted if you have a sympathetic person listening or who is doing the recording to remember things you haven’t thought about for years.

Of course oral history has a role. We were lucky with the bicentenary in 1988 because that was a flourishing time for oral history. Many people who thought ‘my story is not important’ were encouraged which has led to a marvellous twenty odd years for Australian history because we have preserved stories from people who would otherwise be too humble or too meek and think that their lives were not important. Thank goodness that has changed. Hopefully history will never go back to being about just ‘top’ people’s stories but will remain as belonging to all of us.

Getting back to Maybanke Anderson. It was exciting researching and writing her remarkable story which will now hopefully be remembered. Then I did my Doctorate in History as a mature aged student, 55 years old at NSW University where an oral history based study of Australian women and children of Papua New Guinea became a book called ‘Voices from A Lost World’. That work came about because men like my father and Frank Clune talked endlessly about their lives in New Guinea, but women like my mother never mentioned theirs. It was only when my father had died, a very big man in every sense of the word, that I thought to ask my mother and my mother-in-law, who both had had children and lives in New Guinea, what it was like for them.

That led to my doctorate. Helped by Dawn Herman, from Avalon, who lives in a Jolly house, the work was published as ‘Voices from a Lost World – Women and Children in Papua New Guinea’ before the Japanese invasion. I don’t think it’s well known in the Pittwater area, although a lot of New Guinea people came to live here after the war because it reminded them somehow of New Guinea.

Your influences – you grew up in Avalon in the 1950’s when it was becoming a bit of an artists colony, you were I touch with a lot of very strong ideas and very creative articulate people – did that impact you on what you wanted to do?

Definitely. And it influenced me in the way that I learnt you could live well without a lot of money; that creative arts are probably the most important thing, and, as the Jewish people believe, what is inside your head is something no one can take away from you. I believe very much in that – our minds are more remarkable than any computer.

I was so fascinated by the characters who lived in Avalon, many of whom were escaping war memories. They were so determined to live because they’d nearly lost their lives. They were very vibrant people – the damage was there but it wasn’t obvious. They were wanting to live! Many of them had lost everything but they hadn’t lost their lives, their senses of humour, their ability to tell a good story. They were rich in themselves even though we lived in shacks more or less and had outside ‘dunnies’ and many had only a basic education. For us as children, there was no Avalon school so we had to go to Newport. We all crowded in, it was egalitarian. I know I shouldn’t romanticise it, but Newport Public School was a wonderful school for us all. Although, there was the cane – THAT was not wonderful. We all got it – boys and girls.

What was Arthur Murch like?

He was very quiet, not at all flamboyant. I was only a child when I met him of course, he was a much older man. We were fascinated by how his bike was held together with string – he never cared what he looked like. That was a good example for us; it didn’t really matter what we looked like. We were impressed by the fact that he painted these beautiful paintings and lived in a house that leaked, just like most of the rest of us.

If you could be another creature for a day – furred, finned, feathered or scaled – what would you be and do?

I’d definitely be a bird. Like many of us I like my flying dreams and to be, say, a King Parrot, coming back to Avalon every year to rear my babies and flying with my mate for life – I think a King Parrot is what I’d be.

What is your favourite place or places in Pittwater and why?

The Basin would have to be my very favourite place in Pittwater. I have many happy memories of birthday parties and teenage years there. The Basin and the area around it are so unspoiled.

What is your ‘motto for life’ or a favourite phrase you try to live by?

I don’t have one. It changes all the time. I suppose my motto would be to do your best by yourself and others and live as wisely and kindly as you can.

Ruskin Rowe Press Publications

Remembering Avalon

Avalon Landscape and Harmony

Arthur Murch: An Artist’s Life

Maybanke Anderson: Sex, suffrage and social reform

Maybanke Anderson’s Story of Pittwater

Story of Pittwater

The Astor

Voices from a Lost World - Australian Women and Children in Papua New Guinea Before the Japanese Invasion

The Basin. Picture by AJG, 2012.

Copyright Jan Roberts, 2013.