April 22 - 28, 2012: Issue 55

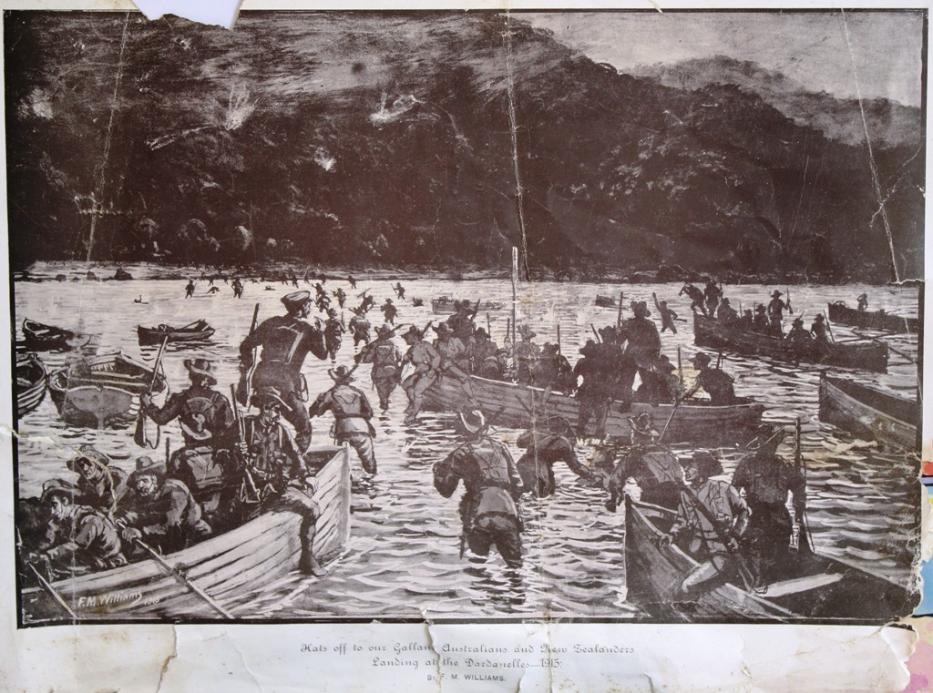

Above: Photograph of painting: Anzac, the landing 1915 by George Lambert (1873-1930), 1920–22 (oil-on-canvas, 190.5 cm by 350.5 cm). The painting depicts the Australian soldiers of the covering force (3rd Infantry Brigade) climbing the seaward slope of Plugge's Plateau which overlooks the northern end of ANZAC Cove. The view is to the north, towards the main range. The yellow pinnacle is "The Sphinx" and beyond is Walker's Ridge which leads to Russell's Top. The white bag that each soldier is carrying contains two days of rations which were issued specially for the landing. Date between 1920 and 1922 (original painting)

Above Col. Ewen George Sinclair Maclagan

Above Anzac Cove, Gallipoli Peninsula, Turkey Photo taken by Adam Carr, May 2002

Above: Cr. James at The Nek, Below: The Narrows. Below this: Femur bone, all photos by and courtesy of David James and family.

Above: 4th Btn. Landing, 8am 25th, April, 1915. Below: Area around The Sphinx and Gallipolli landscape

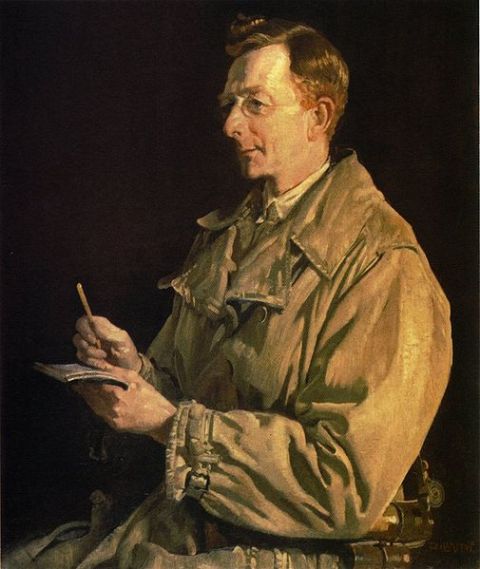

Above Portrait of Charles E.W. Bean, Australian official war correspondent during the First World War. Painted by George Lambert in 1924

Above: Ivo Joy courtesy of David James Cr.

Copyright David James, 2012. All Rights Reserved.

The Landing at Anzac Cove 25th April, 1915 - Fateful decisions and lost opportunity

By David James (CR.)

A recent study entitled “First to Fall” has concluded that 620 Australians (or 2.5 % of the landing force of 16 000 Anzac troops landed on 25 April 1915), died of wounds on that day. Amphibious landings against entrenched opposition are usually very expensive in terms of casualty rates. In this sense, at Anzac the relative lightness of the first day losses comes as something of a surprise that runs against the general impression gained from some historical references. Indeed, Lambert's famous painting of the attack on the North Face of Plugge’s Plateau, seems to be an example of overstatement which contributed to the creation of the Anzac Legend. To be fair, Lambert’s work was painted, after he accompanied the Historical Mission’s visit in 1919 and following consultation on site with Sgt Hedley Howe, an 11th Bn. veteran. There were it is true, casualties of enemy fire on the destroyers, in the boats on the way to the shore and in the initial and later phases of the landing, but these losses and the level of initial opposition were significantly different than the impression that lives in the popular imagination.

One reason for the light casualties at the beginning of the engagement lay in the low number of Turkish platoons then deployed in the area. They were stationed there, basically as sentries and to provide initial opposition to any attempt at a landing which was considered unlikely at that position. And the small size of the defending force reflected General Liman von Sanders belief in the impracticality of attacking uphill over that extremely rough terrain. The defenders did however have a small number of well sited machine guns and the defenders as elsewhere on Gallipoli were quite resolute in the face of vastly numerically superior assault forces.

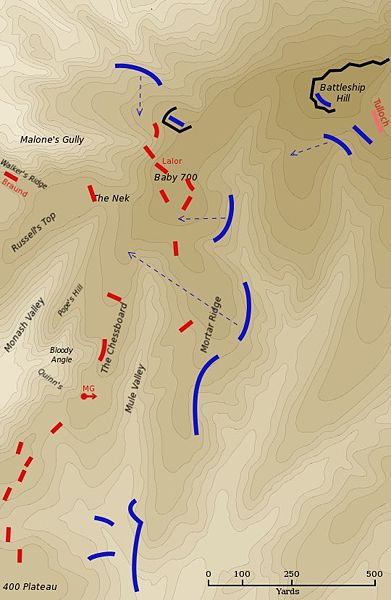

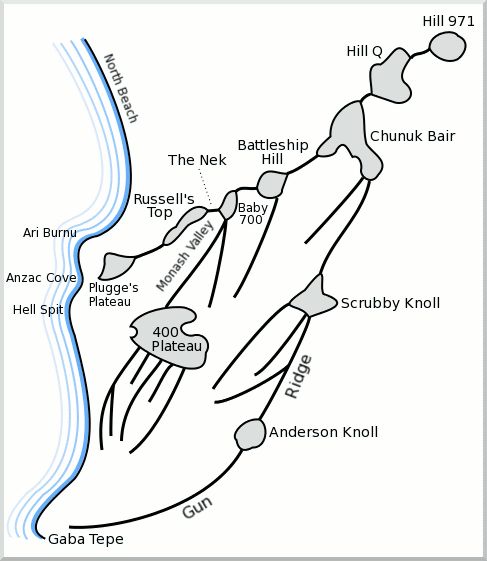

But by 6.00 am many of these defending troops had retreated into the safety of Legge Valley via Wire Gully, where a command post existed in an old farmhouse. Others fell back onto Russells Top and Baby 700 and for some time mounted an effective sniping resistance that held up the Australian advance. By 8.00 am most had streamed back towards Chunuk Bair until Kemal Ataturk intercepted them, assessed the situation and ordered them back into the fight.

One additional factor in the relatively light number of early Australian casualties may have owed itself to the sombre pre-battle assessment of the likely difficulties of the forthcoming battle held by the covering force commander, Colonel Sinclair-Maclagen. It seems these concerns had a large impact on his fateful decision to stop his force well short of its planned objective on Third Ridge. It is even possible that the Brigadier had this contingency in mind before he stepped ashore. Turkish opposition had been largely beaten back (for the time being, anyway) approximately one and a half hours after the first landing. At about this time, Maclagen sent Brigade Major C H Brand forward to 400 Plateau to assess the situation. While doing so, Brand encountered Lt Haig of 10 Battalion, on Second Ridge. The time was about 06.15 am. Brand gave instructions to Lt Haig that were probably the first unofficial amendment of the Battle Plan, “Don’t go too far forward… Don’t go up that hill” --(presumably Third Ridge). It seems unlikely that Brigade Major Brand would issue such a far-reaching order without some previous indication from Brigadier Maclagen.

In 1935, Brand recounted how he had returned to report to Maclagen that “it was hopeless to try to reach and hold the covering position originally assigned”. He said that, “The Brigadier came to the same conclusion”. “How to acquaint the small advanced parties on distant ridges (Mortar Ridge and Battleship Hill) was the problem. Some got back, others did not”.

The impact of the changed battle plan was stark for the advanced parties. Following orders to the letter, they moved inland as fast as possible, and in the case of Tulloch’s party, fully achieved their final rendezvous on the south east slope of Battleship Hill, where they started to dig in and wait for reinforcement by McCays four battalions. As Brand has noted, the difficulty lay in informing these parties of the change of plan. They were, in effect abandoned to their fate. Many were over-run by advancing Turks, some (notably Cowie’s party on Mortar Ridge which was wiped out) were shot, not only by the Turks but also by friendly fire from the rear, such was the confused nature of this stage of the conflict. Tulloch’s party of about 80 digging in on Battleship Hill, took heavy casualties from Turk fire, before deciding to withdraw to Baby 700.

In a commemorative article published in Reveille in 1935, Brand acknowledged that “the opposition was slight at first”. “Quarter of an hour after the advanced units landed the Brigadier and his staff set foot on shore. It was then he realised that the original plan had gone somewhat awry”.

Soon after, Maclagen restructured the Battle Plan, without, it seems, any prior consultation with General Bridges. This radical change of plan might be justified by on-the-ground assessment of the situation, but the evidence for this is slight. Official historian C E W Bean thought that stopping the advance on Second Ridge rather than the targeted Third Ridge saved much potential loss of life. In the final analysis the total casualty rate for the whole Anzac campaign may well have been much, much more. But it might equally be argued that had the covering force been stopped at the lower reaches of Second Ridge but otherwise fulfilled the main thrust of the original Battle Plan, that is, a concentrated and early attack in force by four battalions up the main range via Battleship Hill, then the Anzacs may have achieved much more than the ensuing wasteful stalemate that occurred.

Maclagen was “deeply impressed with the difficulties” on 14 April. He was now concerned about the disposition of Turks centred at Gaba Tepe. If this force moved north against the beachhead he felt, as he put it to McCay, “I assure you they will turn my right if you do not come in”. What evidence he had for this concern is unknown, but considered slight. Neverless his concern was expressed with sufficient force to overcome McCay’s reservations to swing the argument. As it happened, the Gaba Tepe Turks, now known to be 3000 strong, did not come from the right as he had feared, but from Third Ridge in the vicinity of Scrubby Knoll, which was directly to the front.

Well before the landing, General Bridges considered Maclagen a pessimist. Departing Lemnos on 24 April 1918, Maclagen told him, “If we find the Turks holding these ridges in strength, I honestly don’t think you’ll see the Third Brigade again”. In that at least he was very nearly right.

Maclagen’s actions in the highly confused battle situation confronting him have been criticised. He did not go forward to assess the situation for himself. With very little information to go on, Maclagen acted on his intuition and not much more. These shortcomings plus his unilateral decision to radically alter the Battle Plan have led to some charges of a failure of leadership on his part. General Bridges has also been criticised for failing to over rule Maclagen on this issue, in particular his endorsement, with little evidence to support it, of Maclagen’s unilateral diversion of the 2nd Brigade from the planned leftwards attack on the main range to a defensive position on the right.

Maclagen’s Brigade Major, C H Brand, writing in 1935, recalled Maclagen’s final briefing to 3rd Brigade. It is dire and full of foreboding. “Whatever footing we get on land, must be held at all costs. In an operation like this there is no going back. We shall be reinforced as quickly as the Navy can land troops”. His reference to “whatever footing we get on land” reveals underlying uncertainty of what he considered could be achieved.

The briefing consisting of two pages of typescript exhorted his men that even if they “felt that they were on a mad enterprise…. to carry it out wholeheartedly…..we are only small pieces in the game….some pieces have to be sacrificed to win the game”.

He was not the only pessimist. Private W Goodlet 11th Bn recalled General Sir Ian Hamilton addressing 11th Bn troops on his ship on the 24 April thus, “Men of the 3rd Brigade you have been chosen to undertake a feat of arms never heard in the annals of war… to land in an enemies fortified territory…You will land first and keep the enemy at bay whilst the rest land…If you do your work properly a small steam tug will be able to carry what is left of the 3rd Brigade back to Australia…You may fall but others will avenge you…it would be impossible to take you off again if we tried…you would be massacred on the beach”.

Private G H Blay’s diary for 23 March 1915 reads, “We have been addressed by our Colonel to the effect that the 3rd Brigade have been picked (sic) out of all the troops to do the job of landing, 9th 10th and 11th Battns a great honour and expect that only a few will come out of it”.

If correctly reported, it would thus seem that Maclagen was consistently doubtful about the prospects of success for over one month before the landing. Was he defeatist or was he merely more than usually honest in taking his troops into his confidence to reveal to them the truth as he understood it to be.

Any fair reappraisal of command failures on the 25 April 1915 at Anzac would have to also address what went right. Maclagen made two major decisions in the first few chaotic hours on shore. In hindsight (always much clearer) a thoughtful analyst would have to agree with Maclagen’s pre-landing view of the extreme danger of the overextended Battle Plan. Had our troops crossed Legge Valley in large numbers to the Third Ridge it may have resulted in isolated pockets of men, cut-off from resupply and cut down like the Queenslanders were on Pine Ridge. The plan was hopelessly optimistic for a force of 16,000 men and Maclagen was right in that respect. The Turks had a much easier re-supply and logistical burden because of the easier nature of the terrain on their side of the Sari Bair Range. They were advantaged in that they fought on their own well known ground and for their own country. And although outnumbered in the ratio of about three to one, the Turks were, as later events proved, tenacious and brave fighters. Sandy Mac, as he was known to the troops of his Brigade was right to stop his men on the lower parts of Second Ridge. By doing so, he limited his first day losses to less than 800 men, far lower than would have been the case had he blindly followed orders. He must have been a brave man.

But his second and more critical decision, to deflect the 4000 troops of McCays 2nd Brigade away from their allotted task of attacking over The Nek and Battleship Hill and up the main range had disastrous results. Ataturk instinctively knew early on the morning of the 25th that the key to the whole battle lay in possession of the high ground and so it proved to be. Had 2nd Brigade attacked as planned, at the appointed hour thus relieving Tulloch’s party on Battleship Hill, they would still have been confronted by Ataturks 3000 troops on the slopes around and below Chunuk Bair. No one could say how such a conflict would have resulted, but it would have been an almost numerically even battle, which if won by the Anzacs would have meant command over the lower slopes of Second and Third Ridge and more importantly down through Legge Valley and Monash Gully. As it was the Turks denied us this vital control and therefore, after terrible suffering on both sides of the lines, were the ultimate winners.

Loss of the chance to take control of the critical heights, may be seen as a direct outcome of the fateful decision by Maclagen, subsequently endorsed by General Bridges, to switch 2nd Brigade to the right.

Thus was the Anzac attack doomed to fizzle out into stalemate and ultimate defeat.

Sandy Mac’s transparent pessimism (or honesty) was openly displayed to his troops, but it may have been excessive. Sometimes a leader of doubtful enterprise has to conceal his full foreboding in order to give every chance for its success. And if the commander was so openly doubtful how may this have affected his chain of command? As it happened, there were failures of leadership, with one battalion major openly saying he thought the work of the covering force was completed with the capture of First Ridge. Uneven performance and lack of leadership on the part of one battalion commander was compounded by the loss of natural leaders like Clarke and Reid. Some like Leane, who proved to be a daring and resolute commander, were withheld from the early battle, possibly so as to protect Battalion headquarters. There were examples of “straggling”, whereby unwounded troops made their way unbidden to the rear as others were going forward. The number of stragglers has never been quantified, but Bean remarks on this strange phenomenon early in the battle, of two columns of men passing each other in silence, the one on the way to the battle, the other on the way back to the beach. In these first hours of seeing first hand the shocking reality of bullet on bone and muscle and guts and brain, most Australians went resolutely forward into danger and death. But it is undeniable that others streamed back in shock to the beach via Happy Valley, Malone’s Gully and Monash Valley. When belatedly, Bridges came to realise the supreme importance of taking the heights on the left it was too late. The decisive moment for Anzac success had passed by about 9.0 am, when Ataturk, disobeying orders, drove his three regiments at the Australians, finally throwing them back, off Baby 700 and off The Chessboard in the late afternoon.

To all intents and purposes that was it. The Anzacs never achieved meaningful results, in a battle sense, after that, despite all the promise and all the possibility of achieving far, far more than we did. The terrible losses of the August campaign at the Nek and Lone Pine and at Hill 60 and North Anzac, heroic as they were, were in the end an awful waste because they could not and did not change a thing, militarily. We had a brief few hours on the morning of 25 April 1915 when the heights that were the key to the campaign might well have been ours. But that moment passed as surely as the sun set over Imbros on that beautiful Sunday so long ago.

**************************************************************

One of the biggest questions hanging over events on landing day and one of the enduring mysteries of Gallipoli has to do with Maclagen’s unilateral decision to divert McCay’s 2nd Division to the right instead of pursuing the planned attack up on to the main range via the left through Battleship Hill. Did it remove the possibility of a brilliant campaign success on Chunuk Bair? Or did it bring about the salvation of the Anzacs and represent the only realistic chance, albeit a costly one, of holding on to the beachhead.

So here is how the story goes.

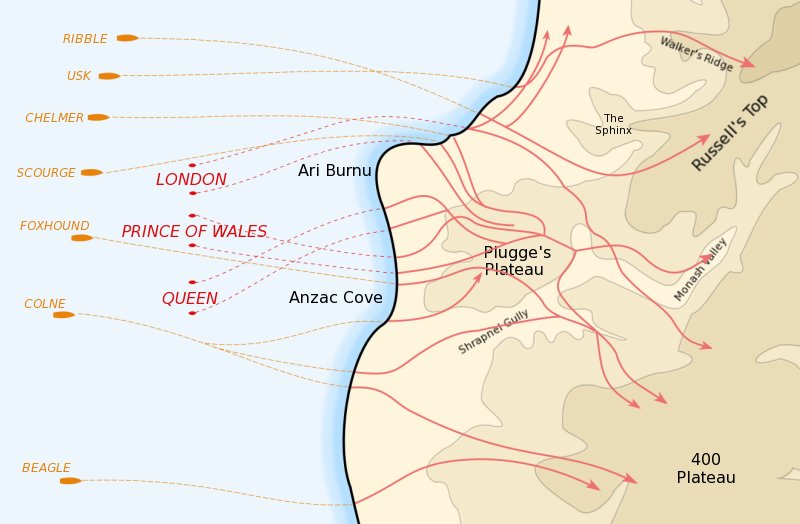

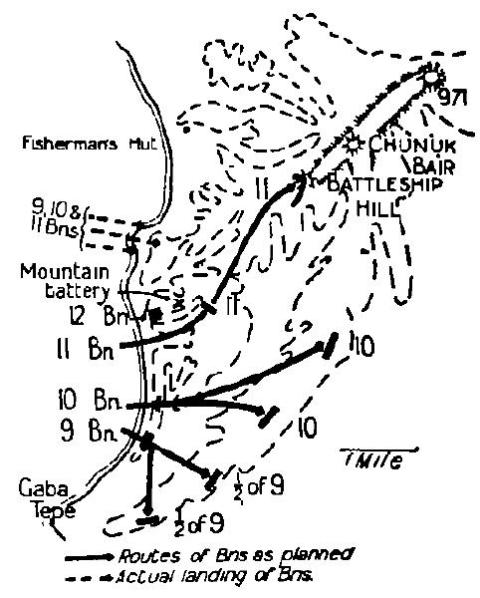

In the dark that followed moonset on Anzac morning, lines of picket boats each towing three boats loaded with men approached the shore. In the picket boat, second from the extreme left of the line, a young midshipman took a fateful, unilateral decision to shift course to the north because, he later says, he had seen in previous days, the formidable redoubt of Gaba Tepe and wire entanglements at the intended landing at Brighton Beach. Peering through the darkness he sees the looming bluff of Queensland Point and mistaking it for Gaba Tepe deliberately steers two points (22 degrees)to the North. This forces the entire line to the North.

This inspired action by a lowly mid-shipman drove the entire line of “battleship tows” to the north, with the consequence that most of the force landed in the slight but welcome shelter of Anzac Cove, thus averting many casualties in the wire and under the guns of Gaba Tepe.

Destroyers “Ribble”, “Usk”, “Chelmer” and “Scourge” carrying the remainder of the Third Brigade inched their way close inshore, coming under fire from Turkish machine guns as they did so. (One early 11th Bn casualty was fatally wounded on the deck of “Chelmer”). These Turkish machine guns were located on at least four sites; on Ari Burnu, in a trench halfway up the slope leading to Plugges Plateau, below Walkers Ridge and at Fishermans Hut. These men from the destroyers disgorge into ships lifeboats and row themselves the short distance to the shore under fire. More casualties occur in the boats and on the beach.

The northward displacement of the landing boats by about one and a half miles conferred great benefits upon the attackers. Because the terrain was so rough, the Turks had virtually excluded it from consideration as a viable landing place for a large force. And the three battalions of the covering force are all much closer to their assigned covering positions.

But there are losses, shocking for troops in their first battle, as they see and hear the effects of enemy bullets hitting home for the first time. Farther up on North Beach virtually the whole complement of a lifeboat is destroyed by the Fishermans Hut machine gun fire. In the wild charge up the nearest hills some Australians are shot by their own troops from below despite “strict orders not to load rifles” for this phase of the landing. One casualty, a sergeant and formerly a schoolteacher, says repeatedly as he lies dying, “ I told them, I told them no rounds in the breach”. Captain Annear is the first officer to die, shot on the seaward lip of Plugges Plateau, also possibly the result of friendly fire.

Shortly after 5.0 am, Turkish resistance is melting away.

Maclagen’s Brigade of four battalions was recruited in all the Australian States. All, including the Western Australian battalion (11th), started recruiting just two weeks after the declaration of war on 5 August 1914.

The recruiting experience in Katanning (a wheat farming and timber getting region of south-western Australia) was entirely typical. Sixty seven men applied to enlist, but only six were accepted and signed up on 18 August 1914. In that first heady flush of war, this scene was repeated in towns and cities all over Australia. The general mood and enthusiasm in the community in favour of the war had been spurred by visits by Lord Kitchener and General Sir Ian Hamilton several years earlier. Continuing news of mobilisation and war preparations by the Powers fed into this popular mood. Then Crown Prince Ferdinand and his bride were assassinated in Sarajevo in July 1914. Now the contending powers of Europe had all the justification they needed in order to let slip their previously mobilised armies. Thus began what arguably turned out to be the world’s worst and most destructive war.

Kitchener’s 1910 visit to Australia had been no idle tourist jaunt. Sensing the likely direction of world events, he was on a mission to assess the cannon fodder potential of the far flung arms of Empire and to condition the colonials towards full participation if the need arose. For our part we needed not much convincing. Love of the mother country and Empire was a very powerful force that raised few dissenting voices. Soon the Australian Government had all healthy young men marching and drilling in compulsory military training.

Ivo Brien Joy, fourth son of Frederick and Caroline Joy of Badgebup near Katanning was fairly typical of these young men rushing to enlist on the outbreak of war. Raised with his brothers and sisters on a 1200 h.a. sheep and wheat farm, he was fit and strong, good at cricket, football and horsemanship. He had recently started work as a bank teller in the Union Bank, Katanning. His few personal effects, a razor and a book of Lowell’s poems, were all there was of him returned to his grieving family. In the year prior to enlisting, he had fulfilled his military service obligation in the Twenty-Fifth Light Horse Regiment. Just after his nineteenth birthday, on 14 August 1914 he was amongst the six recruits selected from sixty seven applicants in Katanning in the formation of the 11th Battalion. Shortly after, he marched them out to the railway station on their way to Blackboy Hill camp near Perth. His record shows his clear leadership potential; Corporal two months after recruitment, Lance Sergeant one day later, 16th Section Commander on 1 Jan 1915.

Mordaunt Leslie Reid came from a different mould. He was a foreman of the Kalgoorlie Electric Company producing power for the boom gold mining town; thirty two years old at the time of his enlistment and naturally fitted to organising and leading men, he was to win a commission as Lieutenant Reid and ultimately to command 15th platoon D company at the landing. Mort Reid was very popular; an “inspiring leader,” according to historian Charles Bean. Big and barrel chested, he led by example and never asked his men to do a thing he would not do himself. His wife Pauline was a nurse by profession and the two would have had a comfortable combined income.

Mordaunt Leslie Reid came from a different mould. He was a foreman of the Kalgoorlie Electric Company producing power for the boom gold mining town; thirty two years old at the time of his enlistment and naturally fitted to organising and leading men, he was to win a commission as Lieutenant Reid and ultimately to command 15th platoon D company at the landing. Mort Reid was very popular; an “inspiring leader,” according to historian Charles Bean. Big and barrel chested, he led by example and never asked his men to do a thing he would not do himself. His wife Pauline was a nurse by profession and the two would have had a comfortable combined income.

The difference between enlisted men and non-commissioned officers in terms of pay scales and status was significant. There was an even greater distinction for the commissioned officers. Some of the enlisted soldiers privately hoped for promotion to non-commissioned officer and ultimately to officer rank. Some of the diaries of married men in particular held at the Australian War Museum reveal these hopes of advancement to secure a better future for their families, particularly sad when the writer did not return. The high casualty rates endured by the Battalion on the first day at Gallipoli removed many of those who led the attack. Some who performed well and managed to survive got early advancement opportunities. Two landing day sergeants of the 11th received Distinguished Conduct Medals for their work on the left of the Landing and in the first few weeks of battle, subsequently received their commissions.

The composition of the 11th Battalion is interesting. Although the average age at enlistment appears to have been in the low twenties, there were examples of older men in their thirties and even forties. These were usually successful professional men like Mort Reid destined in the main to form the initial officer complement. There were also a number of men who had fought in the Boer War and they were accorded a reverential status that was not always entirely justified by subsequent events. Professional British Army trained types were fewer in number (3rd Brigade Commander Maclagen was one such) but those of this description mostly held the highest ranking commissions in the unit. Recent research has revealed the surprising fact that 250 of the enlisted recruits or 25% of battalion strength, had been born in the United Kingdom. Many of these migrated as young men looking for work in years leading up to the war. Given the high selection criteria that operated in the first draft this meant that many high calibre native born applicants must have been passed over and so this neat fraction might indicate a deliberate policy of selecting 25 % British born men. Whether or no, the great performance of the 11th Bn on Gallipoli indicates that the British born acquitted themselves just as creditably as the native sons.

The convoy bearing the 1st Australian Division departed from Albany for the voyage to Egypt on 1 November 1914. It was soon established in training camp at Mena near Cairo. No decision on which theatre of war to deploy the colonial troops had yet been made, because Churchill was not able to finally persuade the War Cabinet in favour of the Dardanelles campaign until 28 January 1915. In the meantime the troops drilled endlessly in the desert sand. On 1 January 1915 the battalions were organised into the modern four company configuration, and most of the troops posed that day for the now famous photograph taken on the Great Pyramid (below).

That is where you can see Lt Mordaunt Reid and Sgt Ivo Joy in what was probably the last photograph ever taken of them. Reid is kneeling up on Lt Colonel Lyons Johnston’s right side in the middle front two rows comprising the offices. All the men are standing and sitting behind. In between the third and fourth row behind the double front rows of Officers and seven in from the left is a happy looking sergeant, mouth open and obviously making some remark addressed to the front.

Above: Great Pyramid Picture. Below: Rare lithograph by Narrabeen resident F M Williams, property and courstey of David James Cr.