March 3 - 9, 2013: Issue 100

Quong Tart's Tea House

Julian Ashton and his art.

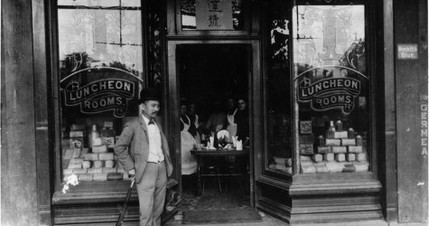

Quong Tart outside luncheon rooms, possibly at 777 George Street, 1886-1898, Photographer Unknown. Gelatin silver photograph, 20.5x29.2, Tart McEvoy papers, Society of Australian Genealogists 6/26 no.3

Copyright George Repin 2013. All Rights Reserved.

THE CHANGING FACES OF SYDNEY

By George Repin

As part of its programme of exhibits demonstrating aspects of the social history of New South Wales, in 1985 the Hyde Park Barracks presented an exhibition called The Changing Faces of Sydney. The starting point for the exhibition, which remained open for several years, was the 1850’s because up to that time the city’s character was dominated by its convict beginning. Change came with the discovery of gold in 1851. From that time successive waves of immigrants arrived, each bringing a different set of customs and traditions, leaving their mark on the city.

On the second floor of the beautifully restored Hyde Park Barracks building, visitors could discover, from the stories of selected individuals, and items displayed illuminating aspects of their lives, the impact that the immigrants had on the life of Sydney after the 1850’s.

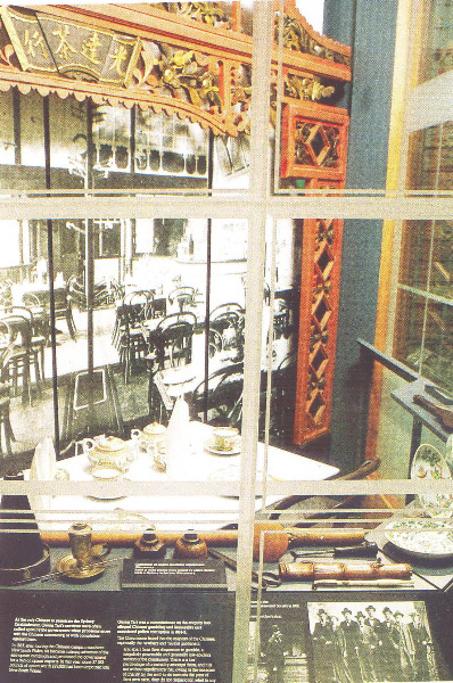

As an example, one section of the exhibition was devoted to the story of Quong Tart, a successful Chinese merchant who lived from 1850 to 1903. Quong Tart was what could be called a totally assimilated migrant in that he married an Englishwoman, Margaret Scarlett, and achieved a prominent position in the society of Sydney. On the other hand he also maintained close ties with the Chinese community, visited China on several occasions and had honours bestowed upon him by the Chinese Government. He was unique for his times.

An enlarged photograph of Quong Tart’s shop in the Royal Arcade, one of the Quong Tart Tea Houses which flourished in Sydney at the turn of the century, was a major feature of the display. Actual panels from one of the Tea Houses, cut from Australian red cedar in about 1890, pierce-carved with decorative Chinese symbols and painted to simulate Oriental lacquer, framed the photograph. The panels displayed the Quong Tart and Co shield with “Quong Tart Tea House” written below in Chinese characters.

Items of Chinese export ware porcelain (dishes, cups, tea pots) were displayed on a white linen tablecloth to show how tables were set. Some items which had been made to order for Quong Tart were monogrammed ‘QT’.

The overall display also included items which, while not related to Quong Tart, provided an insight to life in the Chinese community at the time – including brass and ivory hand-held scales for weighing small quantities of gold and other substances, and a collection of 19th Century opium smoking equipment (pipes, lamps, spatulae, scissors and a small chimney) seized by police during raids in Sydney.

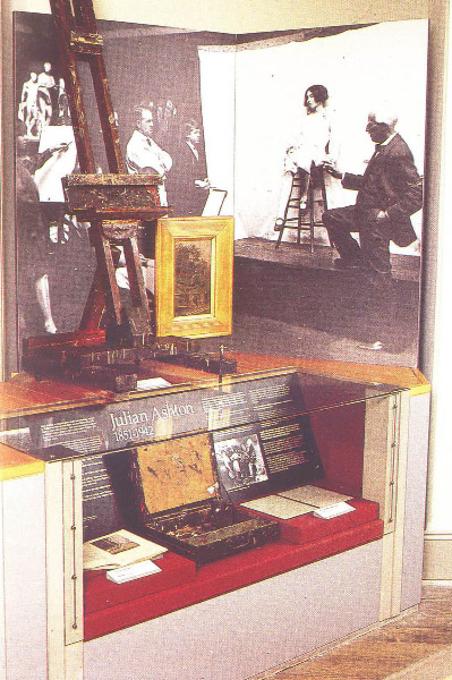

Another migrant featured was Julian Ashton, whose chronic asthma brought him to Australia in 1878. Ashton’s real impact on the Sydney art scene was as a teacher. He established an art school and many of his students became world famous artists among whom were George Lambert, Elioth Gruner and William Dobell.

In another area there was a “mock up” of seating from a Repin’s Coffee Inn. Ivan Repin, a mining engineer from Russia, like so many other migrants, could not start again in his old profession but succeeded spectacularly in a new endeavour. His chain of coffee shops filled a need in Sydney’s social life and stimulated a revolution in coffee-drinking habits.

Images are from ISBN 0 7305 14722 published by the Trustees of the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences 1985

Ivan Repin's Coffee Shop.