August 7 - 13, 2011: Issue 18

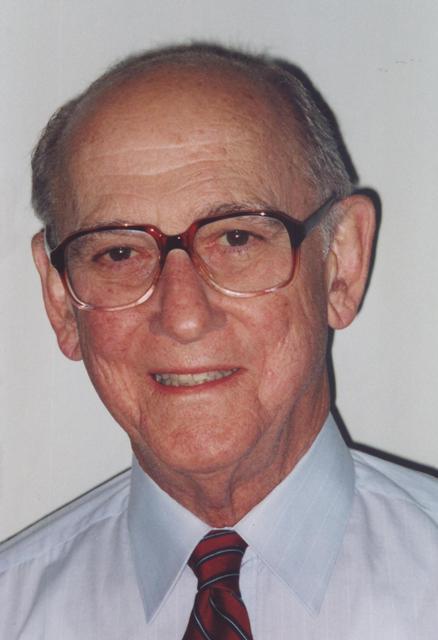

GEORGE REPIN

In 1994, coming from the Eastern Suburbs where he had lived all his life, George Repin moved to a house in Clareville, designed and built by his architect daughter. An old weekender that the family had owned since the early 1970s’ previously was on the site.

In 1994, coming from the Eastern Suburbs where he had lived all his life, George Repin moved to a house in Clareville, designed and built by his architect daughter. An old weekender that the family had owned since the early 1970s’ previously was on the site.

After long term membership of the Rotary Club of South Sydney, in 1998 he completed, at the Pittwater Club, fifty years of Rotary membership and then joined the Pittwater Mens Probus Club.

His career has been busy and varied. He is a medical graduate with postgraduate qualifications in Public Health and in Industrial Medicine, a Fellow of the Royal Australasian College of Medical Administrators, a Fellow of the Australian Institute of Management and an Honorary Fellow of the Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia. He was Secretary General of the Australian Medical Association for

14 years and for 9 years Honorary Director of the Centre for Continuing Medical Education at the University of New South Wales. For sixteen years he was Managing Director of the Repin group of companies, for eight years a Director of the Australasian Medical Publishing Company Ltd. (publishers of the Medical Journal of Australia )and for six years a Director of Medical and Educational Trustees Ltd.

Over the years he has been involved with many professional and industrial organisations, both in Australia and overseas, at Council or Committee level, including eleven years on the Council of the Employers’ Federation of NSW, and a term as president of the Medico-Legal Society of NSW.

He has undertaken consultancies for both the Federal and the NSW State Governments and was made a Member of the Order of Australia in 2006.

THE NINETEEN THIRTIES

Life in the nineteen thirties was hard. Conditions then, with limited social support, are probably unimaginable to many living today in what is to a large extent an affluent society

The call “Cloooothes Props” coming down the street is a lasting memory from the days of the great economic depression. Before Hills Hoists sprouted in backyards every where, and electric clothes dryers in the home were unimaginable, every house had a clothes line – a multi-stranded galvanised wire stretched across the yard - on which clothes were hung to dry. When loaded with wet clothes the lines, unless propped up, sagged and clothes dragged on the ground. The clothes prop was used to push the line up in the middle. Men in ragged clothes, anxious to earn a few pence on which to live, trudged the streets with bundles of dry straight tree saplings on their shoulders. The saplings were cut to leave forked branches at the thinner end which could be used to push up and support the middle of the clothesline.

The call “Cloooothes Props” coming down the street is a lasting memory from the days of the great economic depression. Before Hills Hoists sprouted in backyards every where, and electric clothes dryers in the home were unimaginable, every house had a clothes line – a multi-stranded galvanised wire stretched across the yard - on which clothes were hung to dry. When loaded with wet clothes the lines, unless propped up, sagged and clothes dragged on the ground. The clothes prop was used to push the line up in the middle. Men in ragged clothes, anxious to earn a few pence on which to live, trudged the streets with bundles of dry straight tree saplings on their shoulders. The saplings were cut to leave forked branches at the thinner end which could be used to push up and support the middle of the clothesline.

Other men wandered the streets selling braces (pairs) of skinned rabbits. Chicken was an expensive luxury item which few could afford – reserved for Christmas or for a really special occasion. A family could be fed a tasty but cheap meal of white meat from a pair of rabbits.

There were no supermarkets in those days. Food was bought in a variety of ways.

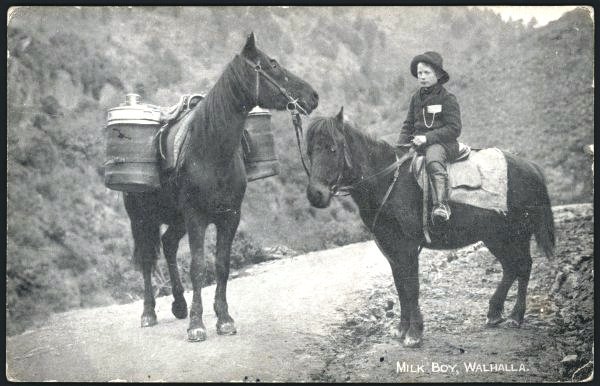

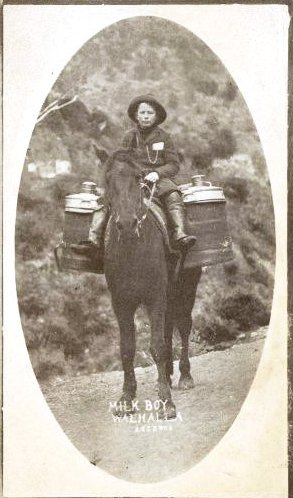

The milkman brought milk in a horse and cart. The decorated body of the cart was a tank holding the milk, with taps at the back. The householder left a billy-can or a covered jug, in most cases with the necessary money, near the front gate. The milkman used a measuring jug to draw milk from his tank and to fill the householder’s container. Delivery of milk in bottles came very much later.

The baker, also with a horse and cart, came to the door with a wicker basket over his arm. Turning back a covering piece of canvas he showed the housewife the breads in the basket to make a choice. This too almost invariably was a cash transaction. During the depression every tradesman had to worry about being paid – yet communities, though poor, generally were honest and any cash left out for a tradesman was safe.

Items such as sugar, flour, salt, grains, rice were bought from a small local grocery shop where the grocer weighed the requested quantity of an item from a bulk container into a brown paper bag. Virtually nothing was prepacked. Butter was cut and weighed from a large “butter box”.

In the absence of refrigerators people relied on ice boxes to keep food cold. These were small tin-lined wooden cabinets with shelves. At the top there was a large container into which the iceman delivered a pre-cut block of ice from his cart. As the ice melted it kept the contents of the icebox cold. Water from the melting ice was piped to a receptacle which had to be emptied periodically.

Some people grew a few vegetables in small plots in their gardens. They watched for the tradesmen’s horses and carts to go past and gathered up their manure as fertilizer.

The postman delivered mail twice each day. Men arriving at work in the city in the morning to be told that they would have to work back could post notes to their wives (or mothers) to let them know – the note arriving in the afternoon mail. Few people had telephones. Great reliance had to be placed on the nearest public telephone box in cases of emergency. Rarely, if ever, were the public telephones vandalised.

There was a sense of community – you knew your neighbours –and in the shared adversity people pulled together. They could rely on a helping hand.

In a material sense so many of us are better off now – but what have we lost on the way?

George Repin

Pictures Left: nlapic4765156, Milk boy on horseback, Walhalla, Victoria, ca. 1905, nla.pic-vn4765328,Boy on pony with horse loaded with two milk vessels, Walhalla, Victoria, ca. 1905, both are postcards.

Above: nla.pic-vn4728505, Booth, Abraham Valentine, 1867-1933, Washing hanging on line, Wagga Wagga Region, New South Wales, ca. 1920s. All Courtesy of the National Library of Australia.

Copyright George Repin 2011.

All Rights Reserved.