February 17 - 23, 2013: Issue 98

Francis Howard Greenway, Macquairies architetct, 1777-1837 GPO Image gpo1_21951, courtesy State Library of NSW.

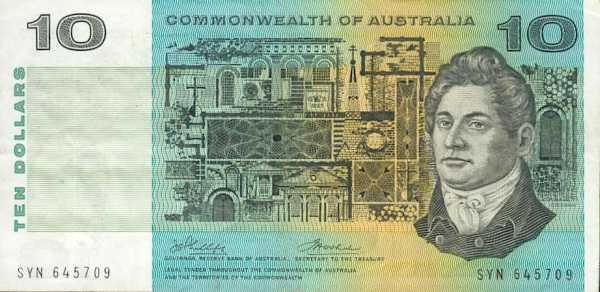

Paper $10 bank note 1972 featuring Francis Greenway

Hyde Park Barracks by and courtesy of J Bar

Copyright George Repin, 2013. All Rights Reserved.

THE HYDE PARK BARRACKS

By George Repin

The Hyde Park Barracks, one of the oldest buildings in Sydney and a splendid reminder of the convict era, were extensively renovated in the early 1980s. The renovations brought out the beauty of the building designed by Francis Greenway, Architect to Governor Lachlan Macquarie. Greenway, a convict from England, with buildings in Bath and Bristol to his credit brought to Sydney’s architecture the elegant style of Georgian England. The building was commenced in March, 1817, its foundation stone was laid on 6 April, 1817 and it was opened on 4 June, 1819.

The Colony was fortunate to have an architect with foresight and courage who designed buildings which would stand for many generations as distinguished and graceful landmarks. Commissioner Bigge, sent out from England to enquire into the state of the Colony commended Greenway’s building in his report, saying “The Style of architecture in which the body of this building has been designed, is simple and handsome, and the execution of the work is solid, and promises to be durable.” The proportions are excellent and the central building gives an impression of size beyond the actual dimensions. The orange colour of the soft sandstock bricks seems to glow.

Governor Macquarie recognised the outstanding merit of the building and rewarded Greenway with a full pardon.

Convicts at that time lived in a mixture of captivity and relative freedom, in practical terms tied to the settlement of Sydney by the hostile nature of the surrounding country which offered only a precarious and uncertain existence to those who escaped.

The Hyde Park Barracks fulfilled a useful purpose in the early days. As Commissioner Bigge wrote “Since the establishment of the convict barrack ........ a considerable number of convicts, varying, and gradually increasing from 600 to 1000 have been lodged there.” Convicts who were doing well preferred to live outside the Barracks, but others welcomed a secure roof over their heads. Those living in the Barracks were required to do “government work” all day but allowed to employ themselves after the hours of government work, and on Saturdays, for their own benefit.

Hammocks in the 'dormitory' by and courtesy of Gerard Charles Wilson, 2010

Those living outside were allowed to leave work at 3 o’clock to earn money to pay for their lodgings and washing.

Accommodation in the Barracks was crowded with four rooms on each floor. “In each room, rows of hammocks are slung to strong wooden rails, supported by upright stauncheons fixed to the floor and roofs. Twenty inches or two feet in breadth and seven feet in length, are allowed for each hammock; and the rows are separated from each other by a small passage of three feet. Seventy men sleep in each of the long rooms, and thirty-five in the small ones”.

By 1820 the number of convicts had increased to the extent that the Barracks could not accommodate them all, and the privilege of living outside was extended.

By the middle of the nineteenth century conditions changed and the Barracks provided lodgings for new arrivals to the Colony with the important difference that they no longer were transported convicts but assisted free migrants. Settlers from England, Scotland and Ireland were given food and shelter in the Barracks until they found work and lodgings for themselves.

Panoramic view of the Royal Mint and Hyde Park Barracks taken from the steeple of St. James's Church, ca. 1871. Creator American & Australasian Photographic Company. Image No. a089322, courtesy State Library of NSW