May 19 - 25, 2013: Issue 111

Christmas Day at Sea.

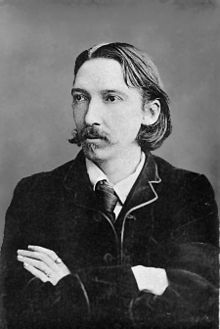

A POEM BY ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON;

In view of the quite recent report of the talented author's death, the following poem from the ballads of Robert Louis Stevenson has a special Interest :

The sheets were frozen hard, and they cut the naked hand;

The decks were like a slide, where a seaman scarce could stand;

The wind was a nor'-wester, blowing squally off the sea;

And cliffs and spouting breakers were the only things a-lee.

They heard the suff a-roaring before the break of day;

But 'twas only with the peep of light we saw how ill we lay.

We tumbled every hand on deck instanter, with a shout,

And we gave her the maintops'l, and stood by to go about.

All day we tacked and tacked between the South Head and the North;

All day we hauled the frozen sheets, and got no further forth;

All day as cold as charity, in bitter pain and dread,

For very life and nature we tacked from head to head.

We gave the South a wider berth, for there the tide-race roared;

But every tack we made we brought the North Head close aboard.

So's we saw the cliff and houses and the breakers running high,

And the coastguard in his garden, with his glass against his eye.

The frost was on the village roofs as white as ocean foam;

The good red fires were burning bright in every longshore home;

The windows sparkled clear, and the chimneys volleyed out;

And I vow we sniffed the victuals as the vessel went about.

The bells upon the church were rung with a mighty jovial cheer;

For it's just that I should tell you how (of all days in the year)

This day of our adversity was blessed Christmas morn,

And the house above the coastguard's was the house where I was born.

O well I saw the pleasant room, the pleasant faces there,

My mother's silver spectacles, my father's silver hair;

And well I saw the firelight, like a flight of homely elves,

Go dancing round the china plates that stand upon the shelves.

And well I knew the talk they had, the talk that was of me,

Of the shadow on the household and the son that went to sea;

And O the wicked fool I seemed, in every kind of way,

To be here and hauling frozen ropes on blessed Christmas Day.

They lit the high sea-light, and the dark began to fall.

"All hands to loose topgallant sails," I heard the captain call.

"By the Lord, she'll never stand it," our first mate, Jackson, cried.

. . . ."It's the one way or the other, Mr. Jackson," he replied.

She staggered to her bearings, but the sails were new and good,

And the ship smelt up to windward just as though she understood;

As the winter's day was ending, in the entry of the night,

We cleared the weary headland, and passed below the light.

And they heaved a mighty breath, every soul on board but me,

As they saw her nose again pointing handsome out to sea;

But all that I could think of, in the darkness and the cold,

Was just that I was leaving home and my folks were growing old.

Christmas Day at Sea. (1895, January 5). Oakleigh Leader(North Brighton, Vic. : 1888 - 1902), p. 7. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article66218576

Robert Louis Balfour Stevenson (13 November 1850 – 3 December 1894) was aScottish novelist, poet, essayist, and travel writer. His most famous works areTreasure Island, Kidnapped, and Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. A literary celebrity during his lifetime, Stevenson now ranks among the 26 most translated authors in the world.

Robert Louis Balfour Stevenson (13 November 1850 – 3 December 1894) was aScottish novelist, poet, essayist, and travel writer. His most famous works areTreasure Island, Kidnapped, and Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. A literary celebrity during his lifetime, Stevenson now ranks among the 26 most translated authors in the world.

Stevenson was born Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson at 8 Howard Place, Edinburgh, Scotland, on 13 November 1850 to Margaret Isabella Balfour (1829–1897) and Thomas Stevenson (1818–1887), a leadinglighthouse engineer. Lighthouse design was the family profession: Thomas's own father (Robert's grandfather) was the famous Robert Stevenson, and Thomas's maternal grandfather, Thomas Smith, and brothers Alan and David were also in the business. On Margaret's side, the family were gentry, tracing their name back to an Alexander Balfour, who held the lands of Inchrye in Fife in the fifteenth century. Her father, Lewis Balfour (1777–1860), was a minister of the Church of Scotland at nearby Colinton, and Stevenson spent the greater part of his boyhood holidays in his house. "Now I often wonder", wrote Stevenson, "what I inherited from this old minister. I must suppose, indeed, that he was fond of preaching sermons, and so am I, though I never heard it maintained that either of us loved to hear them."

Lewis Balfour and his daughter both had weak chests, and often needed to stay in warmer climates for their health. Stevenson inherited a tendency to coughs and fevers, exacerbated when the family moved to a damp, chilly house at 1 Inverleith Terrace in 1851. The family moved again to the sunnier 17 Heriot Row when Stevenson was six years old, but the tendency to extreme sickness in winter remained with him until he was eleven. Illness would be a recurrent feature of his adult life and left him extraordinarily thin.

He compulsively wrote stories throughout his childhood. His father was proud of this interest; he had also written stories in his spare time until his own father found them and told him to "give up such nonsense and mind your business." He paid for the printing of Robert's first publication at sixteen, an account of the covenanters' rebellion which was published on its two hundredth anniversary, The Pentland Rising: A Page of History, 1666 (1866).

In November 1867 Stevenson entered the University of Edinburgh to study engineering. He showed from the start no enthusiasm for his studies and devoted much energy to avoiding lectures. This time was more important for the friendships he made with other students in the Speculative Society (an exclusive debating club), particularly with Charles Baxter, who would become Stevenson's financial agent, and with a professor,Fleeming Jenkin, whose house staged amateur drama in which Stevenson took part, and whose biography he would later write. Perhaps most important at this point in his life was a cousin, Robert Alan Mowbray Stevenson (known as "Bob"), a lively and light-hearted young man who instead of the family profession had chosen to study art. Each year during vacations, Stevenson travelled to inspect the family's engineering works—to Anstruther and Wick in 1868, with his father on his official tour of Orkneyand Shetland islands lighthouses in 1869, and for three weeks to the island of Erraid in 1870. He enjoyed the travels more for the material they gave for his writing than for any engineering interest. The voyage with his father pleased him because a similar journey of Walter Scott with Robert Stevenson had provided the inspiration for Scott's 1822 novel The Pirate.

In April 1871 Stevenson notified his father of his decision to pursue a life of letters. Though the elder Stevenson was naturally disappointed, the surprise cannot have been great, and Stevenson's mother reported that he was "wonderfully resigned" to his son's choice. To provide some security, it was agreed that Stevenson should read Law (again at Edinburgh University) and be called to the Scottish bar. In his 1887 poetry collection Underwoods, Stevenson muses his turning from the family profession:

Say not of me that weakly I declined

The labours of my sires, and fled the sea,

The towers we founded and the lamps we lit,

But rather say: In the afternoon of time

A strenuous family dusted from its hands

The sand of granite, and beholding far

Along the sounding coast its pyramids

And tall memorials catch the dying sun,

Smiled well content, and to this childish task

Around the fire addressed its evening hours.

Underwoods (1887), Poem XXXVIII

Between 1880 and 1887, Stevenson searched in vain for a place of residence suitable to his state of health. He spent his summers at various places in Scotland and England, including Westbourne, Dorset, a residential area inBournemouth. It was during his time in Bournemouth that he wrote the story Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, naming one of the characters Mr.Poole after the town of Poole which is situated next to Bournemouth. In Westbourne he named his houseSkerryvore after the tallest lighthouse in Scotland, which his uncle Alan had built (1838-1844).

In the wintertime Stevenson traveled to France and lived at Davos-Platz and the Chalet de Solitude at Hyères, where, for a time, he enjoyed almost complete happiness. "I have so many things to make life sweet for me," he wrote, "it seems a pity I cannot have that other one thing—health. But though you will be angry to hear it, I believe, for myself at least, what is is best. I believed it all through my worst days, and I am not ashamed to profess it now." In spite of his ill health, he produced the bulk of his best-known work during these years: Treasure Island, his first widely popular book; Kidnapped; Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, the story which established his wider reputation; The Black Arrow; and two volumes of verse, A Child's Garden of Verses and Underwoods. At Skerryvore he gave a copy of Kidnapped to his friend and frequent visitor Henry James.

Journey to the Pacific

In June 1888 Stevenson chartered the yacht Casco and set sail with his family from San Francisco. The vessel "plowed her path of snow across the empty deep, far from all track of commerce, far from any hand of help." The sea air and thrill of adventure for a time restored his health, and for nearly three years he wandered the eastern and central Pacific, stopping for extended stays at the Hawaiian Islands, where he spent much time with and became a good friend of King Kalākaua. He befriended the king's niece, Princess Victoria Kaiulani, who also had a link to Scottish heritage. He spent time at the Gilbert Islands, Tahiti, New Zealand and the Samoan Islands.

During this period he completed The Master of Ballantrae, composed two ballads based on the legends of the islanders, and wrote The Bottle Imp. He witnessed the Samoan crisis. He preserved the experience of these years in his various letters and in his In the South Seas (which was published posthumously), an account of the 1888 cruise which Stevenson and Fanny undertook on the Casco from the Hawaiian Islands to the Marquesas andTuamotu islands. An 1889 voyage, this time with Lloyd, on the trading schooner Equator, visiting Butaritari, Mariki, Apaiang and Abemama in the Gilbert Islands, (also known as the Kingsmills) now Kiribati. During the 1889 voyage they spent several months on Abemama with the tyrant-chief Tem Binoka, of Abemama, Aranuka and Kuria. Stevenson extensively described Binoka in In the South Seas.

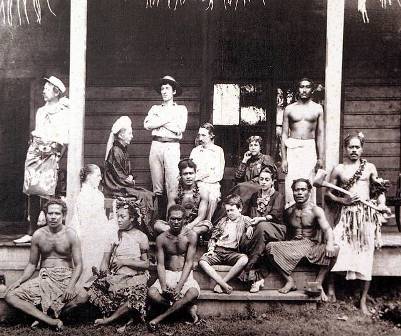

In 1890 Stevenson purchased a tract of about 400 acres (1.6 km²) in Upolu, an island in Samoa. Here, after two aborted attempts to visit Scotland, he established himself, after much work, upon his estate in the village of Vailima. He took the native name Tusitala (Samoan for "Teller of Tales", i.e. a storyteller). His influence spread to the Samoans, who consulted him for advice, and he soon became involved in local politics. He was convinced the European officials appointed to rule the Samoans were incompetent, and after many futile attempts to resolve the matter, he published A Footnote to History. This was such a stinging protest against existing conditions that it resulted in the recall of two officials, and Stevenson feared for a time it would result in his own deportation.

In 1890 Stevenson purchased a tract of about 400 acres (1.6 km²) in Upolu, an island in Samoa. Here, after two aborted attempts to visit Scotland, he established himself, after much work, upon his estate in the village of Vailima. He took the native name Tusitala (Samoan for "Teller of Tales", i.e. a storyteller). His influence spread to the Samoans, who consulted him for advice, and he soon became involved in local politics. He was convinced the European officials appointed to rule the Samoans were incompetent, and after many futile attempts to resolve the matter, he published A Footnote to History. This was such a stinging protest against existing conditions that it resulted in the recall of two officials, and Stevenson feared for a time it would result in his own deportation.

The author with his wife and their household in Vailima, Samoa, c. 1892

On 3 December 1894, Stevenson was talking to his wife and straining to open a bottle of wine when he suddenly exclaimed, "What's that!" asking his wife "Does my face look strange?" and collapsed. He died within a few hours, probably of a cerebral hemorrhage. He was forty-four years old. The Samoans insisted on surrounding his body with a watch-guard during the night and on bearing their Tusitala upon their shoulders to nearby Mount Vaea, where they buried him on a spot overlooking the sea. Stevenson had always wanted his 'Requiem' inscribed on his tomb:

Under the wide and starry sky,

Dig the grave and let me lie.

Glad did I live and gladly die,

And I laid me down with a will.

This be the verse you grave for me:

Here he lies where he longed to be;

Home is the sailor, home from sea,

And the hunter home from the hill.

Stevenson was loved by the Samoans, and his tombstone epigraph was translated to a Samoan song of grief which is well-known and still sung in Samoa.

Robert Louis Stevenson. (2013, May 15). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Robert_Louis_Stevenson&oldid=555256422