January 1 - 7, 2012: Issue 39

BUSHRANGERS HILL

Glorious View from the Summit.

by DOROTHEA DOWLING

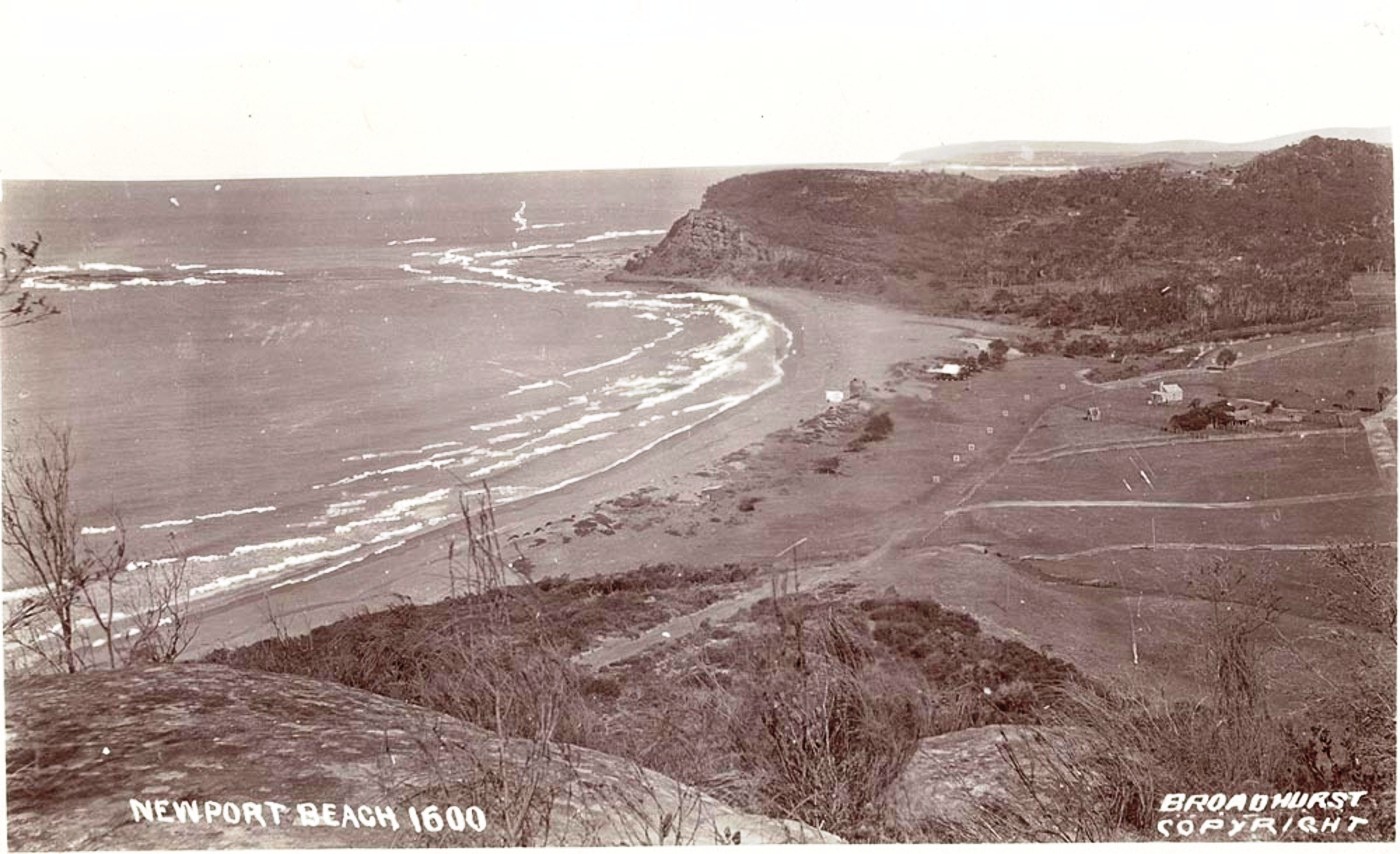

It rises in sugar-loaf formation overlooking Newport Beach-a distinct landmark all silhouetted against a backcloth of deepest blue.

Its ascent is by no means difficult, and once the slope is conquered and its rocky summit scaled the sightseer is liberally rewarded with a delightful panoramic view for hiss scant pains. Here he can take his choice between the peaceful beauty of the sleeping river, fringed with mangrove trees and studded here and there with yachts and small crafts, while on his right the vast ocean rises to meet the sky in varying shades of blue and the restless surf pounds on sandy beaches which appeal when viewed from the height, so symmetrically divided from each other by their high green headlands. There is an air of freedom in the fresh salt breezes, and the weary traveller is aware of mingled feelings of peace and exhilaration as the green of the hills and the blue of sea and sky merge and swim before his fascinated vision.

BUSHRANGERS' HILL. (1935, November 9). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 13. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article17227564

Colourful Images Copyright Pittwater Online News, 2012.

ON BUSHRANGER'S HILL

by THE SPECTRE

Rest, and be thankful. On the verge

Of the tall cliff, rugged and grey,

At whose granite base the breakers surge,

And shiver their frothy spray,

Outstretched, I gaze on the eddying wreath

That gathers and flits away,

With the surf beneath, and between my teeth

The stem of the "ancient clay."

" Here you are," said our guide, " here's where the bushrangers used to come and hide in the old days."

The bushrangers showed good taste, truly, in their selection of a retreat, though it is hardly likely that artistic considerations influenced them in their choice. The knowing old hands - the men who had run the old gamut of villainy and were now being hounded down again by the law - only chose the resort because of the commanding view of the country all about. Lying perdu here they could keep their eye on the whole coast from Port Jackson to Broken Bay ; the track to Newport ran almost under their nose, and, given a proper watch, a surprise was impossible. So the bush- rangers' hill became famous in the convict days, and from all parts of the country the men who had taken to the bush drew toward the lonely eyrie. Then, when the place began to get unwholesomely crowded, the troopers would make a rush; but long ere they could reach the hill its occupants would be gone, and nothing but a smouldering camp fire left to mark the spot. Some old hand, doubtless, standing where the trigonometrical cairn now makes a black mark against the sky, had seen the heliograph-like flash of the troopers' swords hours before; had watched the little band as it forded the Narrabeen Lagoon, and long before it could even reach the track which leads up to the foot of the hill, had given the alarm signal which had once more scattered his mates all over the bush.

The process must have been repeated many times, and so, years after, when a scanty fringe of settlement began to creep up and around Pittwater, and to dot its indented shores with little flower-covered homesteads, the place kept its name. And then in later days a man, armed with a theodolite and a compass, and various other mathematical instruments, struggled up the top of the mass of rock. He also found the commanding position of the hill of value, though he acted from motives far different from those which guided the old bushrangers. Ho simply wanted a prominent point to form the apex of one of his primary triangles, a point which could be looked up to and its angle measured for miles around. So, to make sure of the point, and to prevent any blundering surveyor measuring the angle subtended by the wrong piece of rock, he planted a stout pole, having a pyramidical cairn of stones by way of foundation. Then he put a couple of discs, like railway following signals, on top of the pole, and went away quite contented with his work.

No one goes to the place much now ; a few city visitors sometimes find their way up the hill, and after saying "how pretty, " remark that it must be time for lunch, and so find their way down again. Even the little black-and-tan hotel dog has got tired of the hill. He wagged his tail joyfully when he saw that we were going for a walk, and even condescended, in his patronising way, to accompany us along tho dusty road. But when we commenced tho ascent of the hill he protested. "Can't see what you stupid people want to climb the hill for on a hot day like this. There's nothing at the top except some ugly rocks, not even a 'possum or a wallaby to chase. Besides I've been there before." So he wagged his little tail and set out on his own account. When we came back to the hotel a few hours later he was quietly resting in the shade of the doorway. "I told you so," he said as he gave us greeting. " Hope you'll take my advice next time."

The absence of the dog, however, did not prevent us toiling steadily up through the tangled masses of fern and flannel flower, till we reached the cairn at the top. It is a pleasant place to sit and think whilst the dull boom of the breakers makes muffled music right under your feet, and the kingfishers flash brightly to and fro in the branches all round. There is a grandeur about the shore line as seen from this bird's-eye point of view. From Barranjoey to the Heads the coast stretches, not straight, but in a series of noble curves fringed with a shining line of yellow sand, and a glistening white circle of breakers. Here and there the reefs jut (with long finger-like points) provokingly out into the blue waters, and the sea lashes at them impotently, sending up clouds of white mist over and around those immovable rocks. It is an old story, as old as the world. For ages the sea, lazily sending in its breakers one after the other, has been striving against those rocks, and for ages the rocks, secure in their position, have declined to move out of the way. The sea is in a quiet mood today. The long blue Pacific rollers are gentle, almost languid in their movements, and they break on the rocks with a deprecating could'nt-help-it kind of an air. They are no longer angry with the rocks, a truce has been patched up, a truce which may last for a day or two at the most, until Mr. Russell sends along another storm, and all is again commotion. The water inside the narrow sand line which forms the lagoon has undoubtedly the best time of it. Nothing makes much difference in this sheltered quarter. Whether it be storm or calm outside, the lagoon remains smooth and peaceful. At intervals, indeed, the sea forces a passage through the sandy barrier, but beyond agitating the water inside a little, no great harm is done. It is curious, indeed, the habit which this Narrabeen Lagoon has of opening and closing its own entrance, sometimes shutting itself off entirely from the sea, as if it aspired to become an inland lake, and at other times admit- ting the great waters freely until it becomes little else but an arm of the sea. Further on still, one can just see the great white college at Manly clearly outlined against the black background of the North Head, and beyond this again the houses of Vaucluse shine out on the southern side of Sydney Harbour. All is clear and bright and distinct as it ought to be on such a day, when the southerly gale of the last week has consented to leave off blowing for a while, and all nature is taking a well-earned rest.

But to leave the ocean and turn round. There is water on this side as well. Not the rough blue heave of the ocean, but the quiet calm of an inland lake. It is Pittwater, that highly-favoured arm of the sea, sheltered in such a way as to be a lake in all but the name. The narrow peninsula slopes sharply down to the water's edge, and the little blue lake extends before us for miles, until at last it seems to turn the corner and disappear, going far away north to meet the ocean again in the stormy Broken Bay. There are tiny ships on this lake -small coasting schooners, which come round here at intervals and load firewood for Sydney. You can see piles of this wood stacked along the bank, waiting until it can be taken off in a primitive fashion to the vessels which are anchored a short way from the shore. The houses are few and far between, and for the most part have a comfortable old settled look, hidden away as they are beneath the masses of almost tropical vegetation. And behind, the orchards slope chequer-board fashion up the green hillsides. At the far end of the bay, where one sees two or three cottages grouped rather closely together, an attempt is being made at settlement on a new plan. The owner, by subdividing his property and selling it in allotments, is trying to gather round him a little artistic colony. Here he hopes the men who wield the brush and the pen will make for themselves homes and create a new art centre. The idea is a happy one, and nature, as if in accord with it, has done her best to make the place of settlement beautiful. She has provided picturesque gullies, full of ferns and palms, and has even laid on a waterfall a couple of hundred feet high. All that is wanted now are a few red-roofed chalets, peeping out from among the foliage, and these, I suppose, will come in time. One artist, indeed, has already built himself an ingeniously designed dwelling - something between a Norwegian hut and a Swiss chalet. Others will doubtless follow, when the public learns the value of local art and extends it a full measure of patronage. For this sort of elegant rusticity, though very pretty and pleasant to look upon, requires a good deal of money, the very thing which artists, as a rule, are lacking in. So the settlement - for the present at any rate - progresses but slowly, and artists, when they want a spell in the country, have to be content with the old- fashioned log hut, leaving tiled roofs and gable ends to the capitalist who can afford to indulge in such luxuries.

There are plenty of other things to be seen from the top of the hill, and though the view at present lacks animation, one can easily pardon this fault for the sake of the peace and quietude all around. Some day, perhaps - one can only look forward with dread to the time - Pittwater, now such a happy smiling inlet, will be the centre of a rushing, bustling, commercial activity. The banks will be covered with wharfs, and the smoke of factories will pollute the pure air of the bush. At present one little steamer weekly suffices to take away all the produce grown in the neighbourhood, and to bring up all the supplies needed by the few fruit-growers who have settled around the shore. But as time goes on this must alter. There is abundance of rich land available, there are miles of deep- water frontage, and there is a harbour practically unlimited in size, and unrivalled for safety. So that, as far as one can see, there is nothing to prevent Pittwater from going ahead, and the hill which the bushrangers loved to frequent may one day overlook a busy city.

ON BUSHRANGERS' HILL. (1891, November 28). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 5. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13868244

Image No.: a924065h, New South Wales, 1879 - ca. 1892. N.S.W. Government Printer, Bushrangers Hill, Newport, NSW. Courtesy State Library of NSW.

Image No.: a106114, [Scenes of Newport, N.S.W.]ca. 1900-1927, Sydney & Ashfield : Broadhurst Post Card Publishers, Courtesy State LIbrary of NSW.