April 19 - 25, 2015: Issue 210

Julie Janson

Julie Janson

Since 1993, the International year of Indigenous People, when her play Gunjies was first performed, this award-winning Aboriginal playwright has been adding value to our culture by travelling the paths less trod. Successive plays including the acclaimed 'Black Mary' and one for children 'Kera Putih' (the White Monkey) - 1998 - celebrate stories and cultures and history - a great reflection of Julie's years as a teacher and her ability to introduce knowledge and fun into learning.

A lady of extraordinary inner and outer beauty, with a passion for communicating and sharing stories, and one of our dynamic resident writers, Julie has put aside being a playwright for a while and recently released her first novel, The Crocodile Hotel.

This week she shares a few insights on what it took and what it takes to produce works that share and develop our understanding of ourselves - where we're coming from, and where we may go to.

Where and when were you born?

I was born on the banks of the Lane Cove River in Boronia Park in 1950. Boronia Park is now part of Hunter’s Hill but it used to be a mostly Housing Commission place in the bush.

Did you grow up there?

Yes; we would spend a lot of time down on the mudflats. My dad, being a man of Aboriginal descent would take us kids out to place crab pots, we’d go fishing in a leaky old rowboat and collect oysters off the river. We spent a hell of a lot of time in the bush and yet we were right in the middle of Hunter’s Hill.

You would have seen changes and be unable to collect oysters there now?

I imagine we probably shouldn’t have collected them then either! The river might have been quite polluted but Dad didn’t seem to think so!

The Boronia Park, or the Boronia Park Reserve, is a waterfront parkland and nature reserve wholly within the suburb of Hunters Hill. The park dates back to pre-colonial New South Wales, with original and widely diverse flora and fauna. Photo: Fig Tree Bridge from Boronia Park - picture by by S Shakey

The park was named after the Boronia ledifolia which is all but locally extinct. Photo: Boronia ledifolia by AJG.

Where did you go to school?

At Hunter’s Hill High School, which was actually a bit rough in those days, hard to believe, but I did quite well. My mum was of an English background and she believed the only way to get out of the working class, which we were firmly in, was through education. She really encouraged us kids to study hard, she was great. My dad was more the outdoors type. He would take us camping up in Maitland Bay and Flint and Steel. We’d sleep in caves up at Flint and Steel! I thought we had a normal childhood until I compared it to other people’s; I’d say ‘didn’t you make beds out of bracken and pile them up and put Army coats over them and sleep by the fire in caves?’ and they’d all say ‘Nooo!, I didn’t’. We would visit our grandparents who had an old house in Chatswood, where twenty or so members of the family lived. There were old sheds out the back with uncles living in them amongst horses, dogs and chickens and my old Aboriginal great granny sitting in the sun. In Chatswood near the Lane Cove bush!

Dad was of Aboriginal descent but always kept this quiet as he was an officer in the Fire Brigade and in those days, in the 1950’s and 60’s, the law stated that no Aboriginal person could have a government job. So he kept it quiet from fear he would lose his job and not be able to support his family – he was a Returned Serviceman from the Second World War having been in Borneo – and a great mate of Uncle Bob Waterer’s, which was how I got to know Uncle Bob when we put those two things together.

Did you continue studying after High School?

Yes I did. Mum encouraged me to go to university and so I went to the University of New South Wales on a Teachers College Scholarship. Nobody ever told me that I couldn’t do what I wanted, so I studied hard and did well, gaining Honours at uni, but I very much wanted to go and live in Aboriginal communities. I was interested to find out all the things that I didn’t know as I’d grown up surrounded by a white working-class people and wanted to find out about Aboriginal people. When I was 22 I went to live out in Bourke for a year and helped set up the first Aboriginal Housing Association, although I don’t know how much help I was, I’d had a baby at that stage. As he refers to himself now :‘I’m my mother’s university love-child’. That’s Morgan. He actually appears in the novel in the character of Aaron, and allows me to express what being a single mother was like then, especially during the 1970’s when so many women were forced to give their babies away.

Was that very challenging for you?

Well, other people lied and said they were married or something along those lines but I was always taught by my family never to tell lies, so I never did, so I would just say I’m a single mother and had this terrible society looking down on you. My family were not like this, my family were very loving, but outside of that…

What sort of problems did you have?

People at university would say ‘well, you’ll have to leave now and get a job as a maid somewhere’. My response was ‘no, I’m doing Honours in Drama and I’m really good at it – I know how to write plays and act in plays, I’m going to go on doing all of that’.

Of course I did find that life was extremely difficult as a single mother in the 1970’s; it was prior to the Supporting Parent Benefit. You came under the category of ‘Food, Famine and Flood Relief’.

I’d line up with all the Aboriginal girls in Bourke and you’d have to go up to the police station at Bourke. The big police officer would look down at you with his big ledger and say ‘are you sleeping with anyone?’. I would nervously say, ‘no’, as all the Aboriginal girls around you would say, and I wasn’t as black as them so he wasn’t quite sure who I was, ‘no, of course I’m not sleeping with anyone’ – even if you felt like saying ‘and who are you sleeping with?’.

He would issue you with a bit of paper, a bit like the Basics Card, and you could go to the supermarket and buy food. You couldn’t buy things like Tampax though; if you had anything like that with you the girl at the counter would say in a loud voice ‘you can’t have that on this voucher, take it back!’; it was humiliating.

The year I was at Bourke was a tumultuous year in some ways for me. I met some amazing Aboriginal Murri people down at the reserve, good friends who I still have today, like Jenny Ebsworth. These are people who are now Aboriginal elders out there in Mt Druitt, some wonderful and extraordinary individuals who never stop working for their people.

I finally began to learn about my own Aboriginal background while there by experiencing what it was like to be with them. They lived in little sheds on the side of the river; they had no running water, no toilets and lived in what you may think is a chicken shed with just a dirt floor.

I’d help Jenny take the water out of the river and we’d boil it over a fire. She would boil the kids clothes – it was an extraordinary experience that opened my eyes as to what Aboriginal people have to live through if they’re traditional Aboriginal people.

There was a shocking amount of illness and a high mortality rate among the children. People were living in worse conditions than you’d see in India, and I went to India.

That shocked me into realising that by getting to know my Aboriginal side I was actually uncovering something I’d grown up removed from; growing up in Boronia Park and Hunter’s Hill was all a bit la de dah in comparison – growing up there you’d hang out with kids going to St. Jospeh’s – I remember dad was in the Communist Party, so we always knew we were working-class and he taught us ‘hold your head up high, you’re as good as anyone’ which has held me in good stead in my life, I can tell you that.

Where did you go to from Bourke?

Back to uni- I knew I had to finish my teaching studies so I did my Dip. Ed. and had a year of terrible poverty. I was living on just a mattress in a small room with a little baby and no money – we lived on Weet-Bix, it was terrible.

I came through that, got my Dip. Ed. and was able to go out as a teacher but there too it was very difficult as a single mother, there wasn’t a lot of support. After a little while I decided the only way I could really cut it was to go back to an Aboriginal community.

I applied for a job in the Northern Territory, was accepted, and found myself at an Aboriginal school on a remote cattle station near Katherine…well, not that near, a five hour drive ‘near’… Northern Territory style ‘near’.

That was amazing as all the people living there were traditional people and there had only been a school there for one year. There were 52 kids in the classroom aged from 4 to 18 and not one single one could read or write.

The people were all still doing the traditional ceremonies, which was an extraordinary experience. The landscape was quite rough – it’s Gulf country. When the rains come it completely floods and washes away the topsoil and you can’t go anywhere near a town for three or four months. It’s very isolated – you live on beef, flour, tea and sugar and a few tins of food. You can get malnourished on that diet and a lot of the kiddies were always hungry. I made sure as their teacher that we always had a beef stew for lunch and damper and we gave them powdered milk. The school always provided that and the kids never missed a day of school because they got a feed. At home, in their camp, often mum hasn’t been successful fishing or nobody has caught a kangaroo and there’s absolutely nothing to eat. So coming to school was important for the children as they got fed.

Did you immerse yourself in the culture while there?

Totally. This was a wonderful experience. I knew we were of Aboriginal descent, that we came from Hawkesbury River people, who were the very first people in Australia to be dispossessed by the British back in around 1810. My great great grandmother was born on the Black Town camp at Freeman’s Reach prior to 1900, so although our family had experienced dispossession, it was distant to me, I was born in 1950.

Once I learned about that, and knew what that was, to live with people who were living on a cattle station which they didn’t own in white man’s terms, it was surreal – 400 Aboriginal people living on a cattle station that belonged to a Hong Kong consortium.

What stands out about your personal experience of this culture?

I learnt to shut up, which is big for a writer or creator. What this means is, if you really want to learn about traditional Aboriginal people you have to learn to be quiet, and learn a kind of silence. It’s a bit like being with an Indian guru; you have to learn to sit and listen to the bush around you. If you sit quietly with an old Aboriginal lady for a while then she will start to sing, or tell you some amazing stories.

In my case a lot of them were speaking in their traditional language, and I of course didn’t have a deep knowledge of that so I would have to get them to speak in a Kriol – an Aboriginal-English, which you can get an ear for pretty quickly and understand people.

I found the old women were the only people besides the kids who would really spend time with me. I knew this from my earlier experience in Bourke, that I couldn’t hang out with any of the men; you just don’t do that unless you want hell to rain down on your head – you stick with the women, just like you do in any other society; the Australian Barbecue – the girls are all together and the boys over near the keg, or a commune in India, women with women, men with men.

By sitting with the old ladies I would be told an enormous amount of things which are all about basically teaching you how to be in the country. They did this because everywhere you went there was a sacred site. If you walked around as a complete ignorant person you were going to make some pretty embarrassing mistakes, and that included talking to men whom you were not supposed to speak to.

To understand this; When you went into a traditional community in those days you were immediately adopted into a family, which myself, husband and son were. This meant you had certain obligations to certain family members, such as certain women would be my mother or my sister or my father for instance – and you weren’t allowed to talk to anyone who was your son-in-law for an example. I’d make mistakes, say to a boy ‘come over here, I’ll help you’ and put your arm around him and someone would shout ‘No! He’s your son-in-law; you can’t put your arm around him’.

It was an amazing couple of years of learning a great deal about culture and wonderful ceremonies – incredible corroborees that would go all day and into the night, and no white people there, just me and my son and my young husband for a while, that was the only way the department would let me go to a remote community. My boyfriend of that time, I asked if he’d like to come with me and he said ‘yes’ and we went down to the registry office. He loved being in remote Aboriginal communities, he fitted right in. The marriage didn’t last but I did get a beautiful daughter out of it. She was born out there and has gone back to live up there now. She is a social worker and feels very at home in the Territory.

Where did you go to from there?

We went to a remote island in Arnhem Land to a much bigger community, a lot of different clans together and some inter-clan fighting, and there were more facilities such as a health centre there.

I was a teacher at the school and did a lot of art and drama as that’s what I’m good at and put on shows at the school. My husband was quite musical and would create bands with the kids. We had an extraordinary few years there – it was a beautiful place; lovely white sand, azure blue sea, no alcohol, it was a Dry community, just lovely.

Unfortunately the Aboriginal health up there was very very poor and my little daughter became very sick as well. There was no picking up the phone to call an ambulance, there were no phones, just a radio, and no Flying Doctor for Aboriginal people in those days, in all those remote communities there was no Flying Doctor who would fly out and pick you up as they did for white people.

A friend of mine put me and my daughter on a plane which went to the Gove Peninsula and we went to the hospital there. I weighed 8 stone and she was half her weight for her age. We went back down to Sydney to visit my mum and I took her to the Children’s Hospital and they said if I take her back there she will die. I decided not to go back, which in one way was a big mistake as I love it up there; if we’d decided to live in Darwin it would have been fine, but this was only a few years after Cyclone Tracy and it was a rough frontier town after that cyclone, so I decided to stay down here and went to live in Balmain and got a job at the University of Sydney Aboriginal Education Center there.

This took a while as I had children to look after and when you are a mum you often have to work part-time. I started writing plays with the Aboriginal students at Sydney Uni, the Aboriginal Education Assistants, and this is when I became a playwright.

What was the first play you wrote?

One called Gunjies, which in the Aboriginal English of NSW means ‘police’, the ‘gunjible’ or the ‘constable’. This was about the time of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody, around 1998 to 1990. When I started writing this play I thought we were writing about a debutante ball out in the country. It was the year of the Royal Commission into Black deaths in Custody, and the Aboriginal students couldn’t get away from it, this was so fixated in their minds and it came out in the play; we ended up writing a play that was about a debutante ball but also about a death in custody.

We received a grant from the Australia Council and put it on at the Belvoir Street Theatre. It was my first ever play and my we made some shocking mistakes; it didn’t go very well and we lost a lot of money. We had wonderful actors though, people like Lillian Crombie and Kevin Smith, wonderful people. We also workshopped at EORA College in Redfern with Justine Saunders, an extraordinary actor and friend. The play only ran for a four week season. It’s published by Aboriginal Studies Press.

After that I started writing my big play ‘Black Mary’ which was about the Aboriginal bushranger from the Stroud area and her role in the life of Captain Thunderbolt as his wife. She kept him hidden in the bush, which she knew how to do as she was Aboriginal.

I was always interested in that story as it was one my dad had told me. He’d say ‘oh Thunderbolt, he’d go out to Windsor and Wilberforce he’d stay with my great-grandparents’ – and I’d go ‘oh, alright’ – and of course, as it turned out, this was a story a lot of people in New South Wales used to tell. Many used to say ‘Thunderbolt used to stay with my great-grandparents’ or grandparents.

This play however was quite successful. We had two productions and one of these was quite a big production as part of the ‘Festival of the Dreaming’ in 1997 prior to the 2000 Sydney Olympics. There were live horses in the show, lightning, rain, a stage as big as a football field, epic. This was a big expensive Belvoir St Theatre production, costing $300,000, and on the 10th night of the production, at the Carriage Works in Redfern, the seating fell down.

Why?!

Because it hadn’t been put up properly. The council closed the show down. I was about to make some money finally. Instead I made very little. People were hurt.

It was very traumatic. I was there the night the seats fell down, it was terrible. A couple of people ended up in hospital with broken jaws, another lady broke her leg, all the lighting was smashed – it was really quite a dreadful experience for people.

I’m sure I had post-traumatic stress but often when you have something like that you don’t realise you have it. I became quite vague, found myself walking out in front of buses, it was very upsetting.

I kept writing though and ended up writing ten plays in all, one of which was put on in America, in Phoenix Arizona, by their Theatre Company. I wrote plays about Indonesia and some have had runs at the Sydney Opera House, The Studio and the Adelaide Festival Center, so I had a good career in that field.

Your new novel “The Crocodile Hotel” – what was the spark that began that?

I’d always thought I’d like to write something about those experiences I’d had when really young out in the Territory. It was such an amazing story. The young husband I had was a writer and I thought, well, he’ll write it – and he never did. As the years went by I thought ‘I’d better get on to this’ and so I wrote a play called ‘The Crocodile Hotel’. This was a big epic play which got shortlisted for the Patrick White Award. I thought ‘this will be a goer’ but unfortunately it’s very difficult to get a play with a big cast on in Australia, especially if it’s a new play, by an Australian woman. People feel safer with Shakespeare. So it didn’t get a production even though it had a full professional reading at the Bali Ubud Writers Festival a few years ago.

In the end we took the first act, which was about the Makassan Traders from Sulawesi coming across to Arnhem Land and my director friend Sally Sussman raised money to bring to Australia some members of an Indonesian theatre company: Teater Kita Makassar. I had workshopped the play with them in in Sulawesi. The wonderful actors and musicians arrived and we rehearsed and created an amazing production with Arnhem Land dancers and the Arnhem Land actor Djakapurra Munyarryun – Djakapurra starred with Lisa Flanagan, who is in the tv movie Redfern Now. We put the play (The Eyes of Marege) on at the Opera House, Studio and Adelaide Festival Centre – it went really well, we had rave reviews, but we only had about six nights of performances in Sydney.

Cast of play The Eyes of Marege

After that I decided I was ready to bow out of theatre, it was too much, and I was so disappointed that the whole of the epic play ‘The Crocodile Hotel’ hadn’t been put on that I decided I would take the parts that were all about the 1970’s in the Territory and I would write a novel. But writing a novel and writing a play is apples and oranges – it took me about four or five years to do it, and I thought I’d give up a few times.

The Australia Council have always been really good to me, I have had quite a few fellowships. They gave me the BR Whiting Rome studio. I said to my husband; I’ve been offered this, we can go to Rome for six months and I can finish writing this novel but I’m not going to go without you; the kids had left home, it will just be the two of us. He said, are you kidding?! I’m packing my bag now. He was able to work while he was over there and I was able to finish the novel, thanks to the Australia Council and the taxpayer really.

If you don’t get that kind of support many don’t actually finish the work, many writers don’t. I was working as a high school teacher during the last few years, which is a very stressful job, so being able to take six months off from teaching to just concentrate on the book, I was able to break the back of it and finish it.

I think I’ve been very privileged to meet some extraordinary people, and every person inspires you and becomes in some way an inspiration to write these great characters. Every person I have met in my life has in some way been drawn upon but are not per sae – for instance, in my protagonist Jane Reynolds, I have created a character who was single and people I know have remarked ‘goodness, I didn’t know you had such a racy time up there in NT’ – which I didn’t, I was married! I thought it would be more interesting to create a character who was single and that would allow her to create more relationships with people within the community.

I think this lightens the story – if I’d just written an account ‘My Life in the Northern Territory as a teacher’ no one would read it; it has to be stimulating. So I did take the most exciting and bizarre things that did happen to me and amplified them and created new fictional characters and even created a whole Aboriginal community and I may cop some flak for that, I don’t know – I do know other Aboriginal writers have done it.

If you could state what the soul of this book is in a few sentences – what would they be?

It’s about Australia recognising that there is a debt to be paid. This land was taken through complete bloodshed and I don’t want to put people off reading the book by them thinking ‘it’s going to make me feel guilty’ – it isn’t and won’t. It is actually to remind us that the land was taken and it was taken by force.

That is something which I don’t think Australians can ever actually get away from and nobody wants to face up to it. It’s a novel that I felt had to be written because when I was in this remote community I found out that right near where I was teaching was a massacre site – and it was in 1929.

Now, my mother was born in 1929, and it seems so recent from that perspective. I was mixing with people who were there on the day it happened. I spent time with people who ran away on that day and escaped. They were the grandmothers and mothers of the children who were at the school!

It was so in your face you couldn’t just go ‘oh, that’s lovely – and I think I’ll buy myself a new car when I go back to Sydney.’

Living here on the Northern Beaches we live in this kind of cloud cuckoo land of beauty where everyone gets on well, lovely place, lovely beaches, but at the heart of it, as I grow more and more into my Aboriginality and the Aboriginal stories of this country, and I am part of a vibrant local Northern Beaches Aboriginal community, at the heart of it is dispossession. So that underpins the novel, but the novel is also quite funny – I can be incredibly funny and sexy and I can be quite descriptive – I can make you cry as well.

It’s not a book about massacre – it’s about people surviving and with the good humour and the love that Aboriginal people have for each other and for other people and how embraced this young character was by them – a complete outsider and suddenly she’s taken in and put in a family – “you’re one of us”!.

Having met traditional Aboriginal peoples, what struck strongest was a palpable dignity. To what would you attribute this?

I think it stems from a tremendous sense of knowing we are living in our own country and that we have been here for 50 thousand years. The whole of this landscape is marked with Aboriginal sites – traditional Aboriginal people will look around you and tell you that everywhere you look, every rock and every tree has some kind of story and meaning. It’s like an enormous great big bible.

When you are in the bush are you aware of an Aboriginal presence?

Yes, especially when I’m in Kuring-Gai National Park. I’ll go to one of the remote parts of this and suddenly turn my head and be aware of an old Koori bloke sitting under a tree who is sharing something in the quietness of that place.

My husband, Michael is great at finding middens and artefacts or sketches in charcoal and it is like the people haven’t been moved. That is what is so wonderful about where we live and places like Kuring-Gai National Park. My youngest son, Byron is also very interested in sites and Aboriginal heritage.

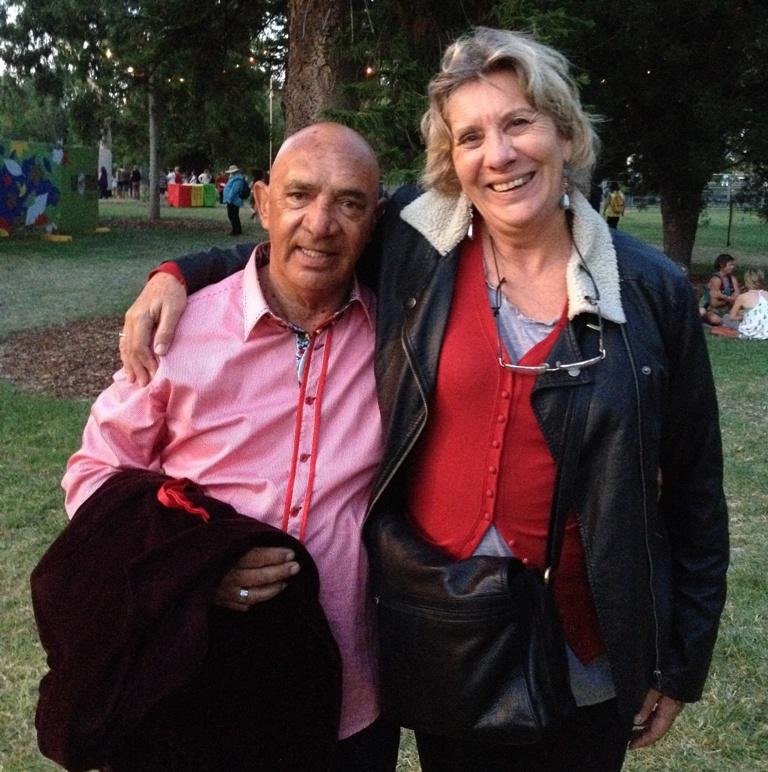

Musician Vic Simms and Julie Janson

What are your favourite places in Pittwater and why?

I love Palm Beach. I think it’s a very important place. I know it’s the place where Bowen Bungaree camped, right there on the beach, and whenever I go up there I can feel Bowen Bungaree and all his family there on the beach. That is a fairly recent history, the Guringai were here from 1817 onwards and the Garigal here for 20,000 years and I get that sense of being in an Aboriginal place. It is also a connection with European history, as you may know that Bowen Bungaree’s father circumnavigated Australia with Matthew Flinders – so you have thatshared history and I always think that’s really interesting about this country. If we could get that it’s not if you’re white or you’re black, but actually that we share the country in a very deep way – if we can appreciate that we have got the best of both worlds then you have a happy community.

I married my second husband 30 years ago atop Sunrise Hill in the reserve there at Palm Beach. I love where I live here in Avalon, especially the Angophora Reserve. That has an Aboriginal burial site that is three thousand years old. It is one of the most important Aboriginal sites on the Eastern sea board.

What is your motto for life or a favourite phrase you try to live by?

Never give up.

We have survived – Aboriginal people have survived – we have survived together with people of European descent. I am of proud European and Aboriginal descent.

And always believe in yourself! My father used to say ‘always support the underdog’ – he was really big on it; if you’re the only person in the room who thinks something about a certain topic, and it’s about supporting the underdog, he’d say ‘fight to the death for the right to support that person’. He was a very wise man in that way.

Website: www.juliejansonwriter.com

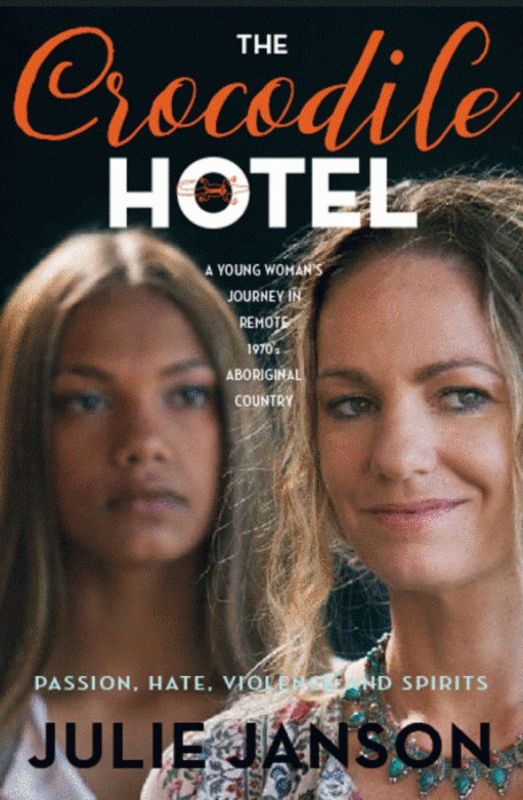

THE CROCODILE HOTEL

THE CROCODILE HOTEL

Author: Julie Janson

Published by Cyclops Press

ISBN 9780980561951

RRP $24.95 (with GST)

Release Date: 28 March, 2015

This story strikes deep into Australia’s heart. An epic novel about a young Aboriginal single mother’s awakening of identity and compassion in a remote Northern Territory community in 1976. This land holds a terrible secret of immense proportions, the earth is red with the memory.

Jane Reynolds is swept up in a year of wonders, as she negotiates her place between the black and white societies. She begins teaching in the caravan school on the remote cattle property, Harrison Station, south of Arnhem Land.

Jane arrives with her five-year-old son Aaron. She meets traditional Aboriginal elders who change her life forever. She finds love with two charismatic men and fights for Land Rights alongside the Lanniwah, while finding respect and redemption for herself.

The great grand-daughter of a Darug Hawkesbury river Aboriginal woman, Jane takes a journey to recognise her identity and is drawn into the world of race relations in the face of 1970s prejudice and discrimination.

There is grim humour, powerful understatement and memorable characters. Jane is sexual, courageous and passionate as she is swept up in a tempestuous story of the Northern Territory that reveals the bloody history of the country and the Lanniwah people’s spiritual magic realism. This recreation may challenge the way you think about Australia’s history.

ABOUT JULIE JANSON:

The Crocodile Hotel is the debut novel by critically acclaimed playwright, Julie Janson. Her plays Black Mary and Gunjie were published by Aboriginal Studies Press (1996). Black Mary was produced by the Belvoir St Theatre for the Olympic Festival of the Dreaming (1997) and by Phoenix Theatre, Arizona, USA.

The Eyes of Marege was performed at the Studio Sydney Opera House and the Ozasia Festival at the Adelaide Festival Centre (2007). Julie is a member of the Burruberongal clan, Darug nation of the Hawkesbury River.

“A story that needs to be told: a riveting account of a young Aboriginal woman from Western Sydney asserting her own identity in a remote Northern Territory community in the teeth of entrenched racism at the beginning of land rights." Linda Burney

Palm Beach from Barrenjoey Headland - A J Guesdon picture.

Copyright Julie Janson, 2015.