June 19 - 25, 2011: Issue 11

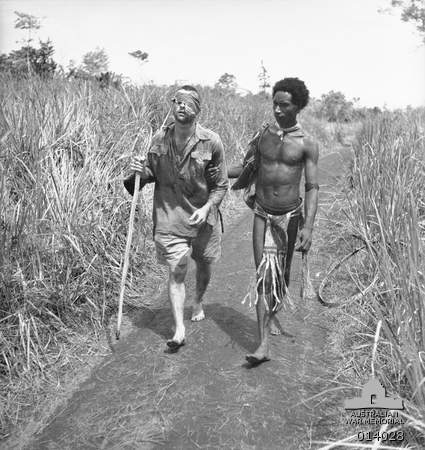

Above: BUNA, PAPUA, 25 DECEMBER 1942. QX23902 PRIVATE GEORGE C. "DICK" WHITTINGTON BEING HELPED ALONG A TRACK THROUGH THE KUNAI GRASS TOWARDS A FIELD HOSPITAL AT DOBODURA. THE PAPUAN NATIVE HELPING HIM IS RAPHAEL OIMBARI. WHITTINGTON WAS WITH THE 2/10TH BATTALION AT THE TIME AND HAD BEEN WOUNDED THE PREVIOUS DAY IN THE BATTLE FOR BUNA AIRSTRIP. HE RECOVERED FROM HIS WOUNDS BUT DIED OF SCRUB TYPHUS AT PORT MORESBY 12 FEBRUARY 1943.

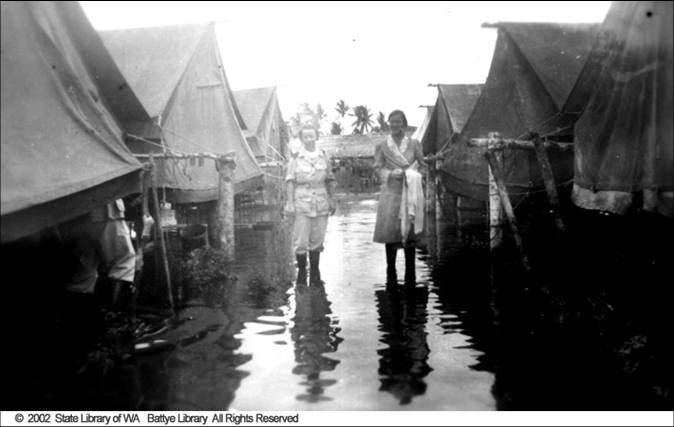

Above: 2/11th AGH at Buna. Below: Ward 13 2/11th at Aitapi, New Guinea.

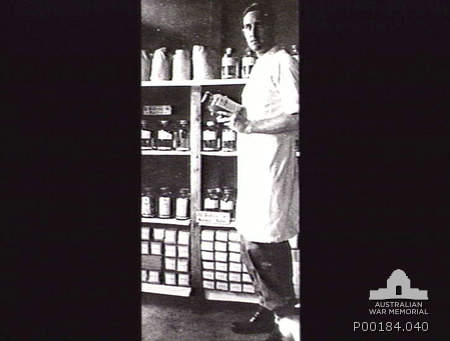

Above: Captain Lowe in Buna Blood Bank.

Above: 2/11th AGH Living quarters at Buna. Below: wounded being brought in through Kunia Grass.

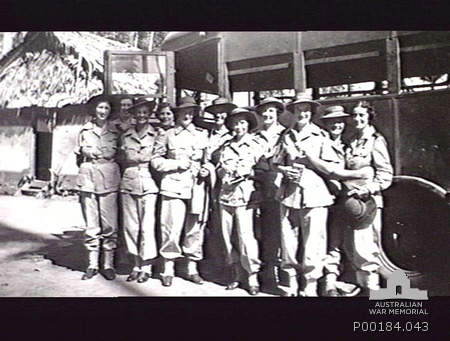

Above: BUNA. 1944. MEMBERS OF THE AUSTRALIAN ARMY NURSING SERVICE, 2/11 AUSTRALIAN GENERAL HOSPITAL. FROM LEFT TO RIGHT: SISTERS UMPHERSTON; CHANDLER; BOWMAN; APPLETON; CAMPBELL; FREEMAN; SULLIVAN; WELLS; JEFFREY; REID-GOLDY.

Below: At Sea, off Papua. 1942-12-14. Members of the AIF disembarking from HMAS Broome to go into action at Buna.

Permalink: http://cas.awm.gov.au/item/041248

Above: The Track at Buna. Below: Henry and Anne's fireplace.

Further Reading:

MACPHILLAMY CHARLES HENRY : Service Number - NX32182 : Date of birth - 12 Jan 1919 : Place of birth - SYDNEY NSW : Place of enlistment - PADDINGTON NSW : Next of Kin - MACPHILLAMY MABRAY

From: http://naa12.naa.gov.au/NameSearch/Interface/ItemDetail.aspx?Barcode=4859619

Atebrin - the anti-malarial drug: By June 1943, it was estimated 25000 Australians in Papua and New Guinea had contracted malaria.

Concord Military Hospital:

Cowra and on Queen Mary to Middle East: http://dadirridreaming.wordpress.com/2011/04/25/memories-of-wwii-a-kangaroo-and-aif-troops/

Glossary of Military Terms: http://www.awm.gov.au/glossary/result.asp

PX Supplies; In today's Army PX and Air Force BX they operate together under the AAFES; In this role he was responsible for the reception and onward movement (deployment / redeployment) of personnel, unit equipment and all sustainment supplies

Harris Scarfe: http://www.harrisscarfe.com.au/about-hs/about-hs.html

Joyce Ellen Cleary, Lieutenant Australian Army Nursing Service, interviewed by Angie Michaelis for the Keith Murdoch Sound Archives of Australia in the War of 1939-45

Discussing pre-war nursing; enlistment in Australian Army Nursing Service; nursing at Concord Hospital; posting to 2/11th Australian General Hospital at Toowoomba; embarkation for New Guinea; contact with American servicemen; availability of drugs; psychiatric cases; camp conditions at Buna, Lae, Madang, Aitape; recreation; uniforms. At: http://www.awm.gov.au/transcripts/kmsa/s00566_tran.htm

Finschhafen: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Finschhafen

New Guinea 1943-44 and

Facts: http://www.awm.gov.au/wartime/23/new-guinea-offensive/

http://www.absoluteastronomy.com/topics/New_Guinea

(Finschhafen is a town located 50 miles east of Lae on the Huon Peninsula. Commonly misspelt as Finschafen or Finschaven Australian forces recaptured the town during the Huon Peninsula campaign on 2 October 1943..)

Noad, Sir Kenneth Beeson

He was with 2nd/5th Australian General Hospital in Greece and later with 2nd/11th AGH in Alexandria where he was officer in charge of the medical division under the command of George Stening. He later served in New Guinea and, on his return to Australia, he commanded the medical division at Concord. He remained a consultant physician on the staff of the Repatriation General Hospital for many years. He gained his MD in 1953 for work he did on infectious disease in the Middle East.

JACK ALEXANDER ISAACS, MBE COUNTRY DENTIST 15-8- 1915 - 11-12- 2009

Soon after he graduated, World War II broke out. He enlisted and served in the Middle East, New Guinea and New Britain. It was for his work with the 2nd 11th Field Ambulance in New Guinea, in the most primitive of jungle conditions, often under enemy fire, that he was awarded the MBE.

Read more: http://www.theage.com.au/national/soldier-became-a-dedicated-rural-dentist-20100218-oivg.html#ixzz1PK99Fh36

The powerful British battleship Prince of Wales and the battlecruiser Repulse that had arrived in Singapore only days before Pearl Harbor, were sunk soon afterwards, when they steamed out to intercept a Japanese convoy landing the invasion force in Malaya.

The loss of these ships, and US naval losses at Pearl Harbor, meant that Australia could count on little immediate assistance if Japan directed its forces towards Australia. Australia had long regarded the British naval base at Singapore as a crucial defence, with SM Bruce arguing for its development at Imperial Conferences in 1923 and 1926. Curtin now appealed to Winston Churchill to send the forces promised in exchange for Australian contributions to the European war. But little more than token forces were forthcoming from Churchill, who was intent on concentrating the imperial forces in the Middle East.

With Churchill’s intentions now clear, and the Japanese army moving south towards Singapore, the threat to Australia was grave. Curtin wrote a New Year message alerting Australians to the danger. His assertion that Australia now ‘looks to America, free of any pangs as to our traditional links or kinship with the United Kingdom’ first appeared in the press on 27 December 1941. It provoked outrage from some Australians, and greatly angered Churchill because it undermined the then secret Anglo–American strategy of defeating Germany before turning against Japan. Curtin wanted the Allies to fight the Japanese with the same vigour as they were fighting the Germans and the Italians. After the Soviet–Nazi alliance was ruptured when Hitler’s army invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, Curtin also wanted the Russians to join the war against Japan.

Rousing Australians to greater effort for their own defence was difficult at times. There was industrial action on the waterfront and many Australians reacted against the increasing numbers of US troops in Australia, especially in Queensland, where most US camps were established. The ongoing controversy over Communism became more complicated after 1941 when the Soviet Union became an ally and not an enemy. Among leading figures in the Russia–Australia Friendly Society were Labor parliamentarians like Maurice Blackburn, and prominent Labor activists like Jessie Street. Curtin was required to manage recurring conflict between this group and former ‘Langites’ like Sol Rosevear. Even more troublesome was leftist Minister for Labour Eddie Ward.

During the Christmas of 1941 and the first weeks of 1942, Curtin called on Churchill to come to the defence of Australia, as promised. On 5 January 1942, he confided to Elsie Curtin, who had left Canberra for Perth the day after Pearl Harbor, the ‘war goes very badly and I have a cable fight with Churchill almost daily’. Aware of the severe stress, colleagues convinced Curtin to take a break with his family and, in late January, he went home to Perth for two weeks.

When Singapore fell (15th February 1942), Churchill pressured Curtin to divert the troopships to Burma, to shore up Rangoon’s crumbling defences. On the urging of his defence advisers Curtin resisted, insisting the troops return to Australia. He did, however, agree to Churchill’s request that two brigades go to Ceylon (Sri Lanka). They spent several months on the island, defending the British colony from an invasion that never came.

For the weeks it took the troop convoys to negotiate the Japanese-dominated waters of the Indian Ocean, Curtin was anxious and frequently called on Ray Tracey, his driver, for a late-night game of billiards or just ‘a yarn’. During sleepless nights, Curtin would pace the grounds of The Lodge for hours. After one Saturday parliamentary session Curtin disappeared – he spent hours walking at night at Mt Ainslie. Defence Department head Frederick Shedden meanwhile screened urgent messages at Canberra cinemas, trying to locate the Prime Minister to approve a despatch.

Curtin’s cabled disputes with Churchill resulted in little reinforcement for Australia, but added to Churchill’s resentment at the Prime Minister’s pressing of Australia’s interests. As far as Churchill was concerned, Australia would have to look elsewhere for its salvation.

From: http://primeministers.naa.gov.au/primeministers/curtin/in-office.aspx

will continue to be the rampart against mite bites.

Pages, F., Faulde, M., Orlandi-Pradines, E. and Parola, P. (2010), The past and present threat of vector-borne diseases in deployed troops. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 16: 209–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03132.x From: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03132.x/full

A little bit about your work with scrub typhus ...

Well these were the first patients we'd ever seen with this disease and it didn't follow a very direct pattern. They picked this up from the - mainly they gathered from the Kunai grass, where these rats lived and on the rats were these mites and if these mites got onto the boys they bit them and it formed an s scar that was the point of entry that ... we felt. And within a very short space of time, they could become unconscious or delirious or semi-conscious or sometimes it didn't affect them very much at all. And they died actually from heart failure in the end and this was sometimes after many days of a coma and it was a very serious disease and we had no known drug. So there were many many hours of total bedside care. Usually we tried to 'special' them and it was very disheartening after many days, sometimes when a patient died or sometimes they got better

Sandfly Fever: Sandfly-borne diseases.

Phlebotomine sandflies inhabit diverse biotopes, ranging from desert areas of the Middle East to tropical rainforests of South America.

Most adult sandflies are crepuscular and nocturnal in their biting activity. They can transmit several sandfly fever group phleboviruses, Leishmania spp., and Bartonella spp.

Sandfly fever. The different species responsible for transmission of sandfly fever viruses have a focal, but wide, geographical distribution [59]. Foci are reported from southern Europe, the Middle East and Central Asia, where these species are endemic. In case groups of non-immune soldiers who have been engaged in endemic areas, high infection rates may occur. Owing to the short incubation period and attack rates ranging from 10% to over 50%, the impact of this virus on the fighting ability of military forces can be highly significant [60]. Thus, sandfly fever has long been a disease of considerable medical importance to military forces (e.g. to the British troops in India, Pakistan, and Palestine, and to Austrian soldiers in Yugoslavia in the nineteenth century). During WWII, sandfly fever was a major problem for forces in the Mediterranean basin, and 19 000 cases were reported among Allied forces [61]. Since then, only limited outbreaks have been reported, among Soviet troops in Afghanistan, as well as in Swedish United Nations troops and Greek troops in Cyprus [62–64]. Sandfly fever was considered to be a major threat during the acclimatization process in endemic areas prior to movement into the Gulf War zones. Curiously, with a single small outbreak, sandfly fever has not yet been reported as a problem in Iraq or Afghanistan, even though leishmaniasis, another sandfly-borne disease, is frequent and of great concern [65,66]. Despite the low frequency of occurrence, a recent seroepidemiological study in the native Afghan population, performed in the Kondoz area, revealed a seroprevalence rate of 9.2% against Naples sandfly fever virus, thus indicating that sandfly fever poses a continuous threat (Dobler et al., IMED Congress, 2007, abstract 16.025).

Pages, F., Faulde, M., Orlandi-Pradines, E. and Parola, P. (2010), The past and present threat of vector-borne diseases in deployed troops. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 16: 209–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03132.x From: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03132 .x/full

Scrub Typhus: Mite-borne diseases

Scrub typhus. Scrub typhus, caused by Orientia tsutsugamushi, is transmitted to humans by the bite of numerous species of larval trombiculid mites (Leptotrombidium spp.), popularly known as ‘chiggers’. It is an acute febrile rural zoonosis that is endemic in the Asian Pacific region from Korea to Australia, and from Japan to India and Afghanistan [94]. During WWII, with the deployment of Allied and Japanese forces into endemic areas, scrub typhus attack rates were very high, sometimes causing more casualties than those related to battles (18 000 cases and 20 000 cases, respectively, occurred among Allied forces and Japanese forces). The lethality rates at that time ranged from 1% to 60% [126].

Outbreaks occurred when troops were in field conditions associated with bivouacs or the establishment of camps. At the end of the war, mite-control regimens consisting of impregnation of clothing with repellents (initially dimethyl phthalate, later benzyl benzoate) and the preparation of camp sites (oiling, cutting and burning of the vegetation over an area of 100 yards around buildings or tents) significantly reduced the incidence rates. During the Indochina War, 6536 cases of scrub typhus and 158 deaths were recorded in French forces but this incidence was probably underestimated [15].

After the implementation of the generalized use of chloramphenicol in 1951, no more deaths due to scrub typhus among French forces were recorded. Although scrub typhus caused no known deaths among American troops during the Vietnam conflict, studies on the aetiology of FUOs conducted throughout the war indicated that 20–30% of such FUOs were due to scrub typhus [35,36]. These results and the reports of outbreaks at the beginning of the conflict suggest that scrub typhus was seriously

Talkie talkies: (Battle Fatigue forms of):

http://www.pbs.org/perilousfight/psychology/the_mental_toll/

Henry MacPhillamy

IN the fields and theatres of WWII it wasn’t just wounds each part of the Services had to battle. In some arenas of conflict local parasites carrying disease afflicted more soldiers then wounds. Many of these viruses had not been encountered before and the Allied Forces struggled to identify and treat Sandfly fever, dengue fever, scrub typhus as well as dysentery. Men were dying from these diseases. Pathologists and Bacteriologists rose among those sent overseas. They were vital to saving lives but severely short staffed and thus recruiting those they met with some training to help. Apart from the wounds that could be seen were those caused by prolonged fatigue and extreme stress. Hospitals on the Fronts were not equipped, trained, or had the time in the midst of battles to treat these too and many of those afflicted were sent home for treatment and then ‘shot over the hill’, discharged. These ‘wounds’ seemed to distress those left behind the most, seeing people who had been standing beside them for months suddenly stagger.

Charles ‘Henry’ MacPhillamy ‘signed up on my 21st Birthday’ and was finally accepted 13/6/1940 and Discharged a week before Christmas in 1945. He had tried enlisting four times prior to then but was told he was close to finishing his University Degree (war began in September, 1939 in Australia) and should complete his studies first. There was also the fact that no one was allowed to sign up prior to their twenty-first birthday as they were considered minors and Henry’s parents (Clifford Ave., Manly) wouldn’t let him go in. Henry had already done AMF (Australian Military Forces) camps from 1937-38 (x3) and 3 months more of camps in 1939-1940 through the University of Sydney and was eager to do his bit. He enlisted at Marrickville on the 13th of June, 1940 and took the oath of Enrolment at Paddington on the 14th of June.

What did they get you to do in WWII Henry?

They never let me go where I wanted to go! I was first put in the 2/1st Field Artillery unit (17/6/1940). By the time we went to camp at Cowra they’d changed it to the 2/1st Artillery Survey. The Survey Unit had three companies; Flash Spotters, Sound Rangers, and the Surveyors. That lasted for a little while in the Middle East, surveying. We went to the Middle East on the Queen Mary (27.4.1941), on her second trip, because by the time we got on board it was her second trip. On her first trip she was still furnished and cooks were going and it was as it was when it was a tourist ship and the troops had a wonderful time, but by the time we got on board, everything had been changed. (Embarked from Sydney, disembarked in ME on 5.6.1941)

How long were you over there?

We were there for about 12 to 18 months. Well it was quite interesting really; when we came home we had to go to Tufi and empty all the petrol out of our vehicles; there were two piers and we were going along one and the American ships were on this one and they were bringing all the PX supplies. Well one of our drivers, he was no fool, he told the boys push one of those jeeps over there and he told them to put 30 cases in the back, which was mostly beer. Then we went back over the other side, to our own ship, and I don’t think anyone was sober on the ship going down the Red Sea.

We were there for about 12 to 18 months. Well it was quite interesting really; when we came home we had to go to Tufi and empty all the petrol out of our vehicles; there were two piers and we were going along one and the American ships were on this one and they were bringing all the PX supplies. Well one of our drivers, he was no fool, he told the boys push one of those jeeps over there and he told them to put 30 cases in the back, which was mostly beer. Then we went back over the other side, to our own ship, and I don’t think anyone was sober on the ship going down the Red Sea.

In Gaza Henry was transferred to 1st AGH (19.6.1941). He also, like many of the soldiers, was treated for Sandfly Fever and was treated four more times up until October 1941 for the same. Henry recalls also having dengue fever and still remembers how ill he felt.

What happened; while I was in the Middle East the pathologist who had started a laboratory came and saw me one day. I told him I did various things while at Uni, including Bacteriology, Chemistry and other things you do in Agri, (Agriculture)and he said ‘you’re just the man I want in my laboratory’ and I said ‘well, I want to go back to my Unit’, and he said ‘Well, I’m sorry you’re not going back, you’re joining my Unit’ .

His was the 2nd 1st AGH, they were in Gaza.

Anyhow, when it was time to go home I was given six other men and we were to establish a forward medical team in Burma. Fortunately that never happened as everyone who went to Burma was either killed or captured.

So we’d gone back to Ceylon. We stayed there probably a week, too long, then we got back on board our ship and I was still doing pathology. The skipper, who was an alcoholic, suspected that some of his crew might have infectious diseases such as gonorrhoea etc. We had a lot of gonorrhoea.

And of course I was called upon to identify them.

Our ship, The Esperence, was part of a convoy that went first to Ceylon. When we left Ceylon we were supposed to go to Burma, and along the way, I think we’d only been out of Ceylon Harbour for two days, those two big battleships were sunk in the Coral Sea, and at that stage the convoy turned around and went back to Ceylon. And we were there for about three days before our Prime Minister (Curtin) countermanded Churchill’s orders and told the leader of the convoy that we were to return to Australia. (During March 1942 the Japanese forces had advanced closer to Australia, already occupying the Solomon Islands and Bougainville, and were circling New Guinea)

He was a labour prime minister, the one who had a slight drink problem but he was a very good prime minister. Curtin was a good man. So we didn’t go to Burma thank goodness. They brought us back to Australia, we disembarked at Freemantle. Then we went around to Adelaide and we were billeted with various Adelaide families. I was billeted first of all with the Commissioner for Railways, and secondly with the Scarves; he was the managing director of Harris Scarf Ltd, big store then in Adelaide; they were a wonderful wonderful family. They were teetotallers. He took me aside one day and said ‘Look, you know we’re teetotallers. If you go into my refrigerator you’ll find a beer there. I’d much sooner you and your friends came here and drank your beer then went to the pub.’

They were also very hospitable, Mrs Strauss had her mother staying with her, and two children, and the other fellow staying with me was a dentist; his son had been born after he left Australia, but he’d never seen his son and Mrs Trause/strauss? Said’ ‘well bring them over, we’ve got room for them.’ So they came over, so what with them, and the two of us (billets), the house was rather full.

The people in Adelaide were utterly, amazingly friendly. They established what they called the Friendship Club and they allowed all their pretty young girls to be there, little knowing what the troops were like.

We were there for about three or four weeks.

So they decided we should stay in Australia. We had to put all our gear on a train and take it up to the border with Victoria and there we had to unload everything and load it onto another train as the tracks (train tracks) gauge for the Victorian railway was a lot wider, and then when we got to NSW border we had to do the same there again. We went up through the back lots of NSW to the border right out in the west and there we had to unload everything again because we were back on a narrow gauge in QLD.

So then we went to Warwick and we stayed at Warwick for about four or five months. We were training there. Finally we went down to, it was between seasons, camped outside of Brisbane (Southport). By that time I was 2/11th AGH (AUSTRALIAN General Hospital) At that stage my work in the Army had nothing to do with fighting at all. I was an assistant Pathologist.

Henry was transferred to 2nd/11th AGH on 25.1.1943

We got back to Freemantle in two to three days and were in Adelaide for about five or six weeks. And then this journey up to Warwick where we stayed for about four or five months. We went down to the coast and we camped there waiting to get a ship to go to New Guinea.

And this is where we had a big SAMFU. Do you know what a SAMFU is? (shake of head)

A self adjusting military *uck up

I’m not sure we can put that in; we’ll put in SAMFU, but not the translation. Those that were in the service will know what you mean.

Yes, they use that word a lot. I remember seeing an Englishman, a Tommy, his bike had blown up and we looked at it and said ‘Do you think you can do something with it?’ and he said ‘No, its an Army vehicle, so F something is F something up.’ (laughs, we all laugh)

So a New Guinea SAMFU?

That’s where we have the second SAMFU. It was rather cold, in spite of the season. I remember in my tent, which I shared with a couple of other officers. The bucket of water was inside and it would have ice on it. This would have been 1943, early Spring. It was cold, so cold. I sought out my CO and said ‘Look the troops are all absolutely frozen’; they’d taken all our winter clothing away and given us tropical stuff for New Guinea and it wasn’t much good for there because it was so cold. I said ‘we need more blankets and greatcoats’. So I was given a couple of men and a couple of trucks and we went up to Wallangarra, to the border point where our train let us off. So I went up to Wallangarra with these three men and two trucks and we filled them up with greatcoats and blankets, took it back to the Unit and three days later it was all distributed. Two days later we got word that we’re going to New Guinea and they said ‘You better return all those’. So that was the second SAMFU.

Brisbane was the point from which many Australian ships were sent to New Guinea. The trip to Port Moresby took around four days.

So then we got on the ship. We were all on the North Coast of New Guinea. Buna was where we spent most of the time in New Guinea. The first stop was on the south coast, then there was Buna, then we went to Finchhafen. We didn’t do much there, only a couple of days. We didn’t set up a hospital at Finschhafen but we did at Buna. It was a six hundred men hospital. We had all the gear to expand it to 1200 if necessary.

Were you a Captain then?

I started off in the Middle East as a Bombardier. When I joined the Medical Service I became a private. Then I progressed up to Corporal, Lance Corporal, Sergeant, Lieutenant, and by the time I got to New Guinea I was Captain. I didn’t get any further then Captain, that as far enough.(promoted to Capt 17.4.1944)

New Guinea was a terrible place. We were there for 19 and a half months. It was a shocker. Pustular dermatitis, sand flies. I never got malaria because I religiously took my Atebrin, which the Army insisted upon, but we did have a Polish skin specialist, a doctor, and identical twins came in with very bad dermatitis and he picked it as being Atebrin dermatitis, which was not uncommon, eventually, and against all orders, he took one of the twins off Atebrin and put him on a normal diet and within three weeks his dermatitis had virtually disappeared. It was never ever publicized. I think if you spoke to any of the service people here they wouldn’t know about it. But I knew about it because we saw the evidence.

Who was in charge of the Hospital at Buna?

We had a proper Military set-up; a full Colonel was the CO. Another one of them was from a big family of five doctors in Sydney. This was the 2nd/11th and they were Corps Troops, meaning that they were not attached to any particular Division, so they could be shifted from one Division to another. Always called 2nd/11th AGH and the last one (docotor of family of five doctors) out died just the other day.

So the men coming in, what were they mainly coming in to be treated for?

At Buna, mainly for wounds. (Also) Scrub typhus.

What is Scrub Typhus? Is it similar to Tick Typhus?

Yes.

What parasite was causing it?

A little bug that was in the Kunia Grass.

The chaps coming in with wounds, where were they fighting?

At that stage we were in the Ramu Valley. Must have been 1944.

How many men did you treat at Buna?

When you’re working in a laboratory you spend a lot of time over the microscope looking at malaria bugs. You also spent a lot of time with culturing feces to try and identify the particular strain of dysentery. There’s one story that goes with that; the Major in charge of the Laboratory, (I was the second one there). I had to go and see my CO and say ‘My senior in the laboratory is ga-ga. He’s not writing the names on the plates when he’s putting them in the incubator’. Anyway, so when we’d find something positive the next day we didn’t know who it belongs to, and he’d been doing this for some time. So they decided they needed to shoot him over the hill, so they shot him over the hill and he was discharged. Then they got another going David Hickson, and David settled in pretty well but after he’d been there a few months he got the ‘talkie talkies’, he could never finish a sentence.

What induced the ‘talkie talkies’?

I think it was just stress. I had a friend there who was a dentist, FH, and he came in as a patient with the talkie talkies, and I was a friend of his so I decided to go and talk to him and it was the most exhausting thing to try and talk to someone that never finished a sentence (paused; sad). They never finished a sentence. He was a good dentist. He set himself up and went out into the country as a dentist afterwards.

So where did you finish the war?

At the Concord Military Hospital. (Transferred to CMH 5.4.1945)

Why were you at the Concord Military Hospital?

Well, I guess they thought I’d had enough time in New Guinea and they brought me back to work in the laboratory.

I was on leave when I was married in Christmas of 1944. I know I had to go back to New Guinea.

You were in Sydney, at Concord, the day they announced ‘war is over’. Can you remember that day, what people were like? Were you one of those chaps dancing in the street and throwing your hat in the air?

Probably. I had a very stern Major who was in charge of the laboratory at Concord. He didn’t drink very much but on this occasion he got high. And he proceeded to, in the Officers Quarters at Concord, which were upstairs, and old B* went along to every room and took all the bedding out and threw it down into the courtyard.

Henry was discharged on 17.12.1945

If you could encapsulate or nominate one positive moment from that time, what would it be?

One of the things that was outstanding to me was the friendliness and generosity of the people of Adelaide. They were absolutely superb.

And what was the worst moment?

Probably the worst moment was when the second pathologist in charge of the laboratory went gaga and had to be sent home. I was left to look after the laboratory and I got dysentery. And I kept on working through, filling myself full of M&B tablets and all they had, and I managed to keep going for about a week before I collapsed and went to hospital, and I remember I slept for a week.

So what did you do after the war finished?

I was unemployed. I managed to get a job writing invoices for the export of wool from Australia to Europe, and I did that for about a year. At this stage I think we may have had one baby. We were living at Neutral Bay in my father in law’s house. After I was sick of writing all those Invoices for wool, I saw an advertisement for two people to learn how to do the valuations for country properties. They wanted a graduate from University and somebody else from Roseworthy Agricultural College, which was in Penrith. So Jack Gilling came in as one and I came in as the graduate. We had the senior officer from the Taxation Department join us. And I learnt the lot from him. He only stayed on for three or four years. I was gradually promoted to Chief Rural Valuer of the Commonwealth Bank. This involved going everywhere in Australia and valuing property and he also did this by valuing sheep; so you could have two sheep for an acre and it was different for cattle.

I worked in the NT and in WA, up in the Ord. when they were trying to establish a cotton industry and in Tasmania, when they had trouble with their apples, in SA when they had gluts of grapes, which used to occur then, but principally in NSW. In those days it wasn’t just a matter of going in and putting a vale on the property and you got the money. In those days you had to go through the annual expenses and the annual income and see if there was enough money left over to repay the loan.

At that stage they had established the old Mortgage Bank and it used to make 25 year loans where it was repayable as principal and capital every year; so they made one annual payment. So you had to establish that they had the income and control of the expenses so there was enough left to meet the repayments. Now these days they don’t bother; you go in and see the manager of the bank and if he likes you you get the loan and of he doesn’t, don’t bother.

Henry had to write how to do a valuation papers for the bank.

I ended up writing a dozen papers to guide those who came after on the format for valuing in every Shire in NSW, and areas within these Shires which showed the annual rainfall, the variation, from year to year, the value per sheep-head or per beast area, depending on whether it was cattle or sheep. But these have no relation to reality now. See, for example, out in the Walgett area you could have one sheep to one acre and that sheep area, was valued in those days as about five or six pounds. Today that same country is thirty or fourty dollars; everything’s changed. We used to say that there’s no room for land to go up any further, but they kept on going up. I’m not sure how they’re working it out nowadays.

I went to the Reserve Bank after that. The Reserve Bank didn’t exist as such, it was the Central Bank and it was within the Commonwealth Bank, but when it was going to be split and become independent I went to the Deputy-governor Phillips and told him I’d gone as far as I can go, I’m Chief Value, I can’t get any further there, is there any chance I can come to the Reserve Bank? He said, I can’t guarantee it but I’ll try.

Anyhow, I was transferred, but I was leant back to the Commonwealth Bank for a year while they got someone else trained to come in and take my place.

For the Reserve Bank I was Chief Valuer and Chief Liaison Officer and I had to go out and interview people in their buildings; how the unemployment was, how the uptake of work was (to keep a check on inflation). The part I enjoyed the most was I used to receive invitations to the Governor’s luncheons and I’d arrange the menu with the cooks.

You liked your food did you?

Love my food. Always.

What’s you favorite dish?

In those days we’d have a nice little roast duck. Had both sweets and cheese. The luncheons were very short occasions (no port and lingering).

So you worked there until retirement?

When I got to 62, and I had married Anne by that stage, the only way I could get to France for any length of time was to retire.

When my first wife died very suddenly of a heart attack I was a very popular man. I was invited to so many dinners with eligible widows in attendance on either side. I got sick of it, I ran way, went travelling to England etc. and at that stage Qantas had a little booklet called Port Eubate (open doors) and in this were a number of chateaus from ones that took up to 16 down to ones that only took one or two people. I picked out two with the idea of learning French; and one was booked out so I took two weeks at the other and that’s where I ended up.

Like most of these Chateaus in France they had a farm dependent on them, attached to them, and the one closest to the chateau decided he wanted to retire and none of his sons wanted to continue the lease, and I’d always admired the building because it didn’t have any cracks in the walls. It was in a state of disrepair, so I fixed it up; put bathrooms in “La Domaine”

Anne and Henry married in 1981. Anne’s father fought, rode and flew in WWI. He went first to the Calvary. After they that he went into the Infantry and was at the Somme. Surviving there he went into train to become a pilot and that was 1916. Anne related how they had about three months training and after that he became a fighter pilot and also a reconnaissance pilot. He fought many German pilots. He again was fighting in the Second World War and ended up a POW for a year before being sent him home. When he died he was 99 and his wife (Anne's mother) was 98.

From 1985 until 2007 Henry and Anne began spending six months in France and six months in Australia. Anne has three children, ten grandchildren. Henry has three children, eight grandchildren and three great grandchildren.

When did you move to Palm Beach?

45 years ago. I bought it before I retired from the bank. 1600 pounds. It was a weekender, and that’s what it was bought for.

Was the chimney here then?

Yeah, there’s a funny story about that; supposedly, this house, and the house next door on that side (right) were part of Madame *, she had stables at Roseville, and after the war she is alleged to have got a carpenter in and carved three feet out of the middle of the building and sent it all down here and put one up next door and this one here. But I don’t believe it because you wouldn’t have a chimney like that in a stable.

What is your motto for life?

I had very little help from my family when I was younger and I have the attitude, as far as my children are concerned, that I shouldn’t help them, that they should find their own feet. I stand behind them, I support them in their endeavours but have always encouraged them to be self-sufficient. And my brother thinks exactly the same way. So my motto would be

“Look after yourself because no one else will.”