March 24 - 30, 2013: Issue 103

Gwynneth Ross

With Anzac Day a little over a month away now we’d like to share some insights by one of the ladies who served during WWII. A gentle soul, with a refined mind that is still sharp, Gwynneth Ross provides us with a clear reminder of how people who ensured Australia was not invaded also paid, all of them, in the decades that followed this war in small and large ways that in their turn, impacted upon and shaped the rest of their lives. Many of the people who survived this conflict cannot speak of it without becoming distressed, still. We are grateful and thankful to them all and especially to Gwynneth this week for allowing us to share a few memories of her own experience.

You

were a sergeant in which service?

You

were a sergeant in which service?

The Australian Army.

Being a Sergeant; what did that mean?

Oh nothing really, it never went to my head at all.

Which year did you go into service?

I went in in 1942, which was a bad year for Australia. Darwin was bombed then, the Japanese were making their way closer to Australia. All I wanted to do was get a gun and go and do something. I was only 17, so I changed my date of birth to go in, and I got in alright but then of course they found out. And they said, well, you can go away and come back in a year’s time, and I thought, well that’s no good, we might be overrun by then, or, they said, we can put you in the Financial Area and you’ve got to go home to your mother every night. So I chose to do that.

Where was this?

This was at the Sydney Showgrounds, at the War Office.

Where was your family?

At Bondi.

So you were catching a tram to and from the showgrounds?

Yes, a tram.

When they admitted you were you trained?

Oh yes, we were at Ingleburn. This was the 22nd of December 1942. We were inducted, we were in huts and we did a lot of marching. We had a Marching Out Parade I remember, with bagpipes playing Waltzing Matilda. There was a Parade Ground up there that would be covered with houses now. I then went to Victoria Barracks for a very short time and then straight to the Finance Department.

What did your duties entail?

Everybody had an Aptitude Test, everybody, to see if you might have been good at cooking and then you were a cook, etc. Well I was good at figures, always was so I went into the Finance Department and there I stayed.

Prior to going into the service you studied piano?

I studied piano with my husband’s sister, that’s how I met his family. She and I started learning at around eight years of age. She and I were good pianists, no doubt about that. We only performed publicly in eisteddfods. I’ve always loved real music; Opera and Ballets. We used to see these at Newtown and saw the Sydney Symphony Orchestra at Town Hall prior to Opera House being built.

The years from 1942 to 1945; what stood out most…the rationing…?

There was rationing but I suppose that really only impacted upon my mother, I didn’t do any cooking. I was really only a girl with a wish to go and do something…you would have too. That's what I remember most...wanting to do something. Even to this day when I think of people who did nothing….

Why didn’t they join up?

That’s what I ask myself. They stayed in their good jobs getting big money while people like my husband were on threepence a day and in conflict zones, or maybe it was five bob a day. Not very much in comparison either way.

Can you remember the shells that fell on Bondi and the Japanese submarines coming into the Harbour?

Oh yes. That was just about when my birthday was, the 27th of May and I think they came in a few nights later. On the night of my birthday, my girlfriend and I, she was one of my bridesmaids later, we went on a ferry to Manly. they shelled Bondi from the ocean; some poor people copped it along the beach front. We were in Fletcher street, which is up on the heights looking down on Tamarama beach, and between Bronte and Bondi beaches. We weren’t affected; it was the ones down low on the beach that got hit.

.jpg?timestamp=1364003102828) Japanese submarines attacked many ships off the coasts of Australia from

1942 to 1943. A list of these can be seen at here On the night of 31

May-1 June 1942, three Ko-hyoteki class midget submarines of the Imperial

Japanese Navy entered Sydney Harbour to attack Allied warships. Only one of the

submarines, designated M-24, was able to fire her torpedoes, but both missed

their intended target: the heavy cruiser USS Chicago. The torpedoes, fired

around 00:30, continued on to Garden Island where one ran aground harmlessly.

The other hit the breakwater against which Kuttabul and the Dutch submarine

K-IX were moored. The explosion broke Kuttabul in two and sank her. The attack

killed 19 Royal Australian Navy and two Royal Navy sailors asleep aboard the

ferry, and wounded another 10. It took several days for the bodies of the dead

sailors to be recovered, with a burial ceremony held on 3 June. (1)

Japanese submarines attacked many ships off the coasts of Australia from

1942 to 1943. A list of these can be seen at here On the night of 31

May-1 June 1942, three Ko-hyoteki class midget submarines of the Imperial

Japanese Navy entered Sydney Harbour to attack Allied warships. Only one of the

submarines, designated M-24, was able to fire her torpedoes, but both missed

their intended target: the heavy cruiser USS Chicago. The torpedoes, fired

around 00:30, continued on to Garden Island where one ran aground harmlessly.

The other hit the breakwater against which Kuttabul and the Dutch submarine

K-IX were moored. The explosion broke Kuttabul in two and sank her. The attack

killed 19 Royal Australian Navy and two Royal Navy sailors asleep aboard the

ferry, and wounded another 10. It took several days for the bodies of the dead

sailors to be recovered, with a burial ceremony held on 3 June. (1)

Left: AWM Caption: SYDNEY HARBOUR, 1942-06. THE NAVAL DEPOT SHIP KUTTABUL WHICH WAS DAMAGED BY A JAPANESE TORPEDO DURING THE RAID ON SYDNEY HARBOUR BY JAPANESE MIDGET SUBMARINES ON 1942-05-31.

A week later, on the 8th of June 1942, just after midnight again, a Japanese submarine I-24 travelled at periscope depth about 9 miles south west of the Macquarie light near Sydney. The I-24 surfaced and pointed its deck gun towards Sydney. Commander Hanabusa gave target instructions to gunnery officer Yusaburo Morita to aim directly at the Sydney Harbour Bridge. As they travelled in a north west direction towards the coast, Morita fired his deck gun across the bow of I-24. He fired 10 shells within 4 minutes. The shells came down in the eastern suburbs of Rose Bay, Woollahra and Bellevue Hill. No 1 Simpson Street Bondi was also hit. Fortunately only one gentleman was injured in fracturing a foot as a result of this attack.

Japanese shelling of Bondi, courtesy State Library of Victoria. Image No 0- 2355037

Mid 1944… D Day…

1944, that was the year I had to have my appendix out. They sent me to the 113th AGH at Concord Hospital and I was confined to bed after the operation so I wasn’t one of the ones but I can picture still people gathered around the wireless because it was the 6th of June, when the D Day landings occurred.

What was it like hearing about that?

Well, none of us really realised what this meant and that forever after this would be marked as a day to remember. My husband and I have been there a few times, to the beaches of Normandy, and seen all the crosses…thousands of them…all Americans. Of course we, the Australians, had no troops on the ground. We had Australians on ships and in aircraft but we had no soldiers on the ground, so it was mostly Americans that were killed….and fields of Germans too of course…these crosses, they all belong to someone.

You went to Europe six times though?

Yes, we got the travelling bug; we didn’t start until about 1970 though. The boys were old enough and sensible enough. We both wanted to see the Normandy beaches so we went back there twice, the second time through the friendship of a person. We had someone showing us around and telling us all about it. It was very nerve wracking.

1945…you hear the war is over…what was that day like?

I don’t think it impacted terribly much because things just went on as usual for a long time. It took a long time to bring troops home from overseas…there were so many boys that were POW’s. I do remember going to Martin Place and being a part of all the people there. It was kind of unbelievable, surreal, but nothing seemed to be any different because everybody went back to work the next day.

So life after war was difficult too…rationing still, lack of materials to build a home…

Oh yes, you had to be happy with what was available. My husband came home on the Duntroon mid May 1946. I was still in uniform, I didn’t get out until early September 1946; there was a lot of things to process with the boys who were getting demobbed. We were married late September 1946. We bought, as did most people, a little two bedroom fibro house because that’s all there was. You couldn’t buy a lovely brick house; people didn’t have the money anyway.

Where did he serve?

Well, he was a Matilda Tank driver and he was in the New Guinea campaign at Milne Bay. He came home from New Guinea after the Coral Sea campaign, when things had been quite successful, which was the Americans mostly, with our ships as well. We became engaged then, I was nineteen.

Doug Ross, Milne Bay, 1942.

He went back, over to New Guinea but of course we (at home) didn’t know what was happening…then. What he was doing was training with American landing craft and they were training how to land tanks off the landing craft. This was training for the next campaign which was going to be Borneo. He was with the 7th Division there then, and part of the Balikpapan landing. They would learn how to land the tanks into surf and onto the beach. I think they lost three fellows, they drowned. They were country boys who weren’t used to water. Doug grew up at Clovelly, I grew up at Bronte; he was a good swimmer and the water wouldn’t have fazed him but these poor boys who had to do this in training hadn’t that experience. The book I gave him on his regiment lists them, that they died in training.

Where did you meet your husband?

I knew him because Betty and I were studying together (his sister- pianist) so I knew the Ross household; I knew Mr and Mrs Ross, her parents, and I knew there was a big brother somewhere who was three years older then her. I think we met up at a dance somewhere at Kingsford. I remember being outside and him showing me stars and constellations, pointing out what they were.

You knew he was the one at 19?

I suppose so. You got carried away with the idea of being a bride, and the times too I suppose. People in England went through a lot worse that what we did. They can thank the Americans too, for not being overrun by the Germans… you know we all sneered a bit at the Yanks but they saved everyone.

Why was that; because of the perception that they had better conditions or better food then the Australian boys?

Oh yes ! Their scraps were better food then what our boys had.

One gentleman I spoke to said they knew how to get the fresh fruit form the jungle and swap that for some of the American boys food…

Doug would never look at a pawpaw when he came home…couldn’t, he was sick of them.

What did you do once discharged?

I’m not sure how soon after I got an office job, to start earning and save of course. We each had our pay from serving, Doug would have had much more of course, deferred pay, being overseas for so long. He was there for five and a half years…it’s a long long time. When you think of a man living, the way that they were living, with men, men only, for five and a half years, to come home must have been a terrible shock to the system.

It must have been extremely difficult. A young person, as I was then, I was only 20, you didn’t realise that. In the middle of the night Doug used to so often fling the blankets off, take a few paces and then fall in a heap on the floor. It wouldn’t have been very easy for him. All sorts of dreadful things he went through as part of his regiment.

One he recalled was transporting tanks in the hold of a ship but they weren’t chained properly; they struck a storm and one broke its chains and then with that one cannoning about it hit another one and it broke its chains and they had about four tanks rolling around. They were either going to hull this ship and the ship would have gone down or they’d all go to one side with the ship rolling and that would have made the ship sink. Doug said the Captain had to break radio silence and put all the lights on, and they were throwing bales of rope down in between the tanks as they moved; that too is spoken about in his regiment’s book. So many things in that book he’s made marks beside because he was there.

How long did it take Doug to stop waking in the middle of the night?

Oh, that as going on right until the end, even when he was in the Nursing Home at Collaroy Services when the Parkinson’s became too bad. You know how they sometimes pull up the sides of the bed to stop people falling out?

Well, a couple of times he climbed out and fell on the floor. I said to the Sister, ‘did he say why he did that; was he trying to come home?’; that’s what I thought it would have been, and she said ‘No, he was saying something about, “You’ve got to get off the ship, you’ve got to get off the ship!! Jump off; you’ve got to get off the ship!!”

How old was he then?

He must have been over 80. He was still having the same nightmare.

That’s fifty, sixty years of the same nightmare…

Hmmm.

Did anyone ever speak to him about this?

No, not medically. I think there’s perhaps more medication these days…but not then. The boys that come back from Afghanistan, they must have dreadful things they’ve seen and experienced. Nerve wracking things.. and of course everywhere they walk they could put their foot on something and get blown to bits and die. That really is way over there and not much to do with us, but in our case, our country was threatened, the Japanese were coming ever closer.

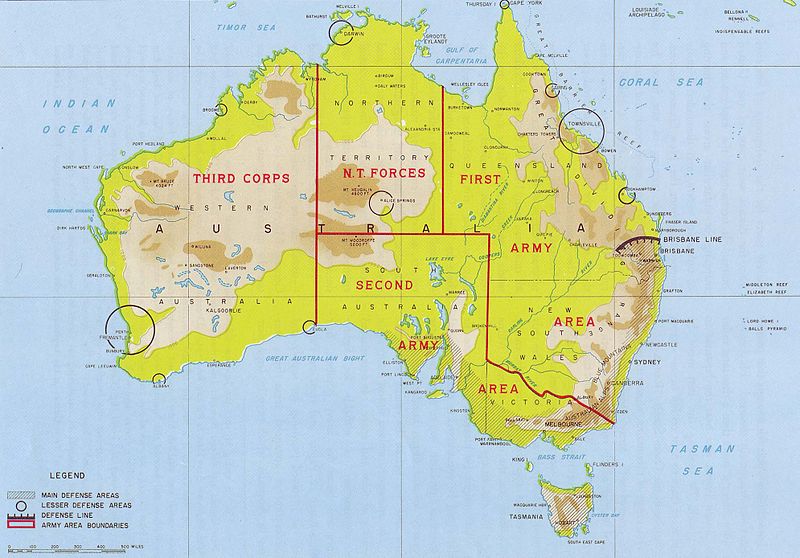

In fact, at the time, there was somebody in the Parliament that devised this idea of the Brisbane Line; have you ever heard of the Brisbane Line? It was to run across from Brisbane to the west; that was where we were going to take a stand, if you please, against the Japanese. Why wouldn’t you want to get a gun and go do something?!!

The 'Brisbane Line' was a controversial defence proposal allegedly formulated during World War II to concede the northern portion of the Australian continent in the event of an invasion by the Japanese. It was rejected by Labor Prime Minister John Curtin and the Australian War Cabinet. An incomplete understanding of this proposal and other planned responses to invasion led Labor minister Eddie Ward to publicly allege that the previous government (a United Australia Party-Country Party coalition under Robert Menzies and Arthur Fadden) had planned to abandon most of northern Australia to the Japanese. A memorandum had been submitted to the Australian War Cabinet in February 1942 (after Menzies, Fadden, and the United Australia Party-Country Party coalition had moved to Opposition), where the General Officer Commanding-in-Chief of the Home Forces, Lieutenant-General Iven Mackay, had advocated that in the event of an invasion, the majority of available Australian forces be concentrated in the area between Brisbane and Melbourne, where most of the nation's industrial capability was located. (Dennis et. al., The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History, p. 107)

Ward continued to promote the idea during late 1942 and early 1943, and the idea that it was an actual defence strategy gained support after General Douglas MacArthur referred to it during a press conference in March 1943, where he also coined the term 'Brisbane Line'. Ward initially offered no evidence to support his claims, but later claimed that the relevant records had been removed from the official files. A Royal Commission concluded that no such documents had existed, and the government under Menzies and Fadden had not approved plans of the type alleged by Ward. The controversy contributed to Labor's win in the 1943 federal election, although Ward was assigned to minor portfolios afterward. Brisbane Line. (2013, March 14). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Brisbane_Line&oldid=543994749

Map from Reports of General MacArthur: The Campaigns of MacArthur in the Pacific Caption: PLATE NO. 11 The Main Australian Defense Areas. Permission to reuse; PD-USGOV-MILITARY-ARMY-USACMH.

So in 1947, you bought your first home, where was this?

Sans Souci. We lived there for 31 years. It was lovely. We didn’t move there until 1949, we were staying with my mother. Then my first son was born, he was just a babe in arms when we moved there. Then two years later my second son arrived. So I had two little boys. They went to Sans Souci primary school.

When did you move out here?

We left Sans Souci about 1980. We built at Avalon, Coolawin road and moved there about 1983. Then later, when Doug was diagnosed with Parkinson’s and we wanted to come in a bit closer to doctors, we moved to Mona Vale.

What was Avalon like then?

There were more high trees, the gums were very high. It was very nice. Of course we were young still, to walk up and down that steep hill.

Doug and Gwynneth Ross

What did you two do on a weekend?

We used to have friends over, have nice food. That’s what you did then. I remember when I was young we would have the baked dinner, or baked lunch. I used to have to be home from the beach for this baked lunch. Then when we were married Doug would be shelling the peas for mum, nobody shells peas nowadays.

Anzac Day is coming up, if you could say something to the generations who have no recollection or experience of WWII or have never met and spoken with a Veteran, what would you say?

Quite frankly I think more people are becoming aware of what went on; certainly more people are attending Anzac Day services and parades or turning up and waving flags. Doug’s Unit is still marching, although most of his mates would be dead and gone now. I think the Unit is continuing they’re just in different tanks; bigger or smaller or improved in some way.

The women march too of course, those that still can. Our girls, at 21 I think, could apply to go to New Guinea, but I think they always picked the girls that were in their mid-twenties who would be more sensible, more level, or those who had some prior training not the young ones. Look at all the nurses that were sent into conflict. They had a terrible terrible time at the hands of the Japanese.

Do you remember the story of the nurses who were forced to walk into the surf at Banka Island and they were machine gunned? There was one survivor, Vivian Bullwinkel; she feigned death until they went away. It was dark, and she could get away. The Banka Island massacre…. terrible.

What is your favourite place in Pittwater and why?

That would have to be Avalon, because of the big trees, beautiful. And where we used to go down and swim in the baths, when we could no longer swim in the surf. Avalon baths are lovely.

What is your motto for life or a favourite phrase you try to live by?

The old one…Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.

References:

1. HMAS Kuttabul (ship). (2013, March 14). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=HMAS_Kuttabul_(ship)&oldid=544169413

2. The Shelling of Bondi by Waverly Council (PDF): www.waverley.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/8667/Shelling_of_Bondi.pdf

Copyright Gwynneth Ross, 2013. All Rights Reserved.