April 21 - 27, 2013: Issue 107

From Strahan to Melbourne for the Union Steam Ship Co

In the winter of 1965, I was 4th Engineer of the MV Kumalla, a Union Steam Ship of Australia vessel on a regular run between Melbourne and Strahan, west coast Tasmania. The company went by the name USS Co. We would laugh at this abbreviated version of the company name, the joke being that what the initials really stood for was, U Shall Slave or U Shall Starve.

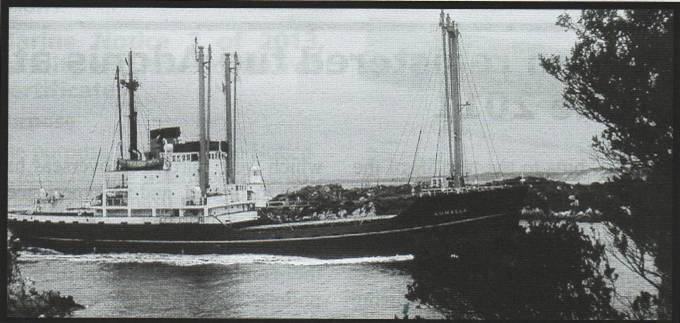

Right: Kumalla, after a Bass Strait crossing at Hell's Gate in 1965-Photograph courtesy of Captain Danny Gunn

Right: Kumalla, after a Bass Strait crossing at Hell's Gate in 1965-Photograph courtesy of Captain Danny Gunn

For all that, USS Co was a good company with a proud tradition forged over many years in Australian coastal shipping, principally on the interstate trade across Bass Strait. Although the fleet had once been much larger they still had 10 or so ships when I joined. The ships were notable for the dark green hull with a yellow driving band, and a white superstructure topped by an orange funnel with black rings and a blacktop. Another notable feature was the unusual top-up derricks (the mast-like cylindrical steel structures used to load and unload the cargo).

Bluff in the bow, with little streamlining, these freighters sat low in the water, fully loaded. They had a reputation as rather gutless in a blow or in a heavy sea of which there was plenty in the Bass Strait and on the wintertime West coast of Tasmania, where the Roaring Forties spend their fury at last upon the battered landform.

While on this run, Kumalla sailed every three weeks or so from our regular Melbourne berth located just under the rail viaduct near our watering hole, the Sir Charles Hotham hotel, (now Flinders Street Railway Station), loaded with general cargo outward bound for Strahan and Queenstown.

Having cleared the notorious Rip at the entrance to Port Phillip Bay, Kumalla would set course for the virtually uninhabited Three Hummocks or Governor Hunter Islands, located off the north-west tip of Tassie. In those days every ship carried a Radio Officer, universally addressed as Sparky. These then were dedicated to their work but strangely often a bit eccentric, which was usually attributed, to the supposed adverse effect on the brain enduring the high frequency dit dah dit of Morse Code for eight hours every day at sea.

If the weather report ahead was a bit uncertain the Old Man would usually have Sparky call up the lighthouse keeper at Maatsuyker for a report on the sea conditions at Hell's Gate, so called because of the narrowness of the entrance to the convict-dreaded, Macquarie Harbour through which we had to pass to arrive at Strahan.

Based on this advice a decision would be made whether to carry on to Strahan or anchor in the lee of the Three Hummocks until the weather down south improved. Although under-powered for the task the careful procedures adopted in the trade ensured that these ships were never overcome in the often stormy seas, always carrying us safely to our destination, albeit sometimes days overdue.

When the weather turned bad it was more than ordinarily important that everyone on board had done his work well and responsibly. Hatch covers needed to be securely Carped. The cleats must not fail in the water swirling on deck and over the covers. All engine room machinery and main engine/s had to have been well maintained and operated without error.

Navigation in these challenging waters was so important and done back then without the benefit of satellite and other modem aids. Kumalla did have radar at the time I was on her. However, it was located in an unusual place atop the starboard mast instead of atop the monkey island. This was presumably to avoid clutter from the high top up derricks that were employed by most Union Co ships.

I cannot remember ever being affrighted in those stormy seas, so confident I was that every other man on board had done and would do each allotted job just as reliably and well as I believed I was doing.

One memorable night in Bass Strait. All day we crested the very large waves. Regal wandering albatross wheeled close over head. Tiny storm petrels (known to seafarers as Mother Carey's Chickens) wings aflutter, feet paddling, fed on plankton borne in the spindrift on the cresting waves. Our ship had made very little forward way all through that long day under the howling onslaught, with the overspeed governor on the British Polar main engine often cutting in, slowing the engine just when we most needed the revolutions. As the bow fell into each trough the nearly exposed propeller raced, partly in air. Large waves struck the hull, causing timber panelling in alleyways

and cabins to creak and groan in time, as the vibration from the shuddering stem coursed the ship's length.

MV Port Huon in a Southern Ocean gate note the spindrift scudding along the face of the seas; also the tarpaulin and cleated canvas hatch cover. Kumatla weathered the

same conditions, too. Photo courtesy of Capt. Danny Gunn.

That night I got up to go to my engine room watch at midnight; something scurried at my feet past my cabin door that I thought was a rat. On closer inspection though, it proved to be a tiny storm petrel, attracted by the light perhaps and somehow blown inside the ship out of the howling winds. I left it sheltering in my cabin and made my way below to tend the noisily rattling main engine. When I came up after my watch I looked for it but the bird was never seen again. How it had got inboard our storm battened ship and what subsequently became of it was a mystery. Some sea stories have it that these tiny, black and white storm petrels are seafarer kin supposed to bring good luck, believable perhaps due to their incredible ability to survive and even relish the stormy seas.

By the mid 1970's Union Steam Ship Company was sadly no more.

Journey’s End. Kumalla arrives at Strahan Wharf 1965. Note the Union Co office next door to the all-important hotel. The point of land astern of the ship is Regatta Point, where the copper pyrites, transported by road from Queenstown, were loaded into the ship by conveyor belt. Photo courtesy of Capt. Danny Gunn.

Kumalla, fine little Scottish-built ship she was, was sold to Hetherington Kingsbury and I again sailed on her for two sugar seasons in 1975 and 76, carrying the raw sugar product from the Broadwater and Harwood Island sugar mills located on the Richmond and Clarence Rivers, Northern NSW to Colonial Sugar Refinery at Pyrmont, Sydney Harbour.

Chief Engineer David James -January 6, 2013.

First published in On Watch, P.6-7., February 2013.

Copyright David James, 2013. All Rights Reserved.