June 21 - 27, 2015: Issue 219

Adrian Boddy

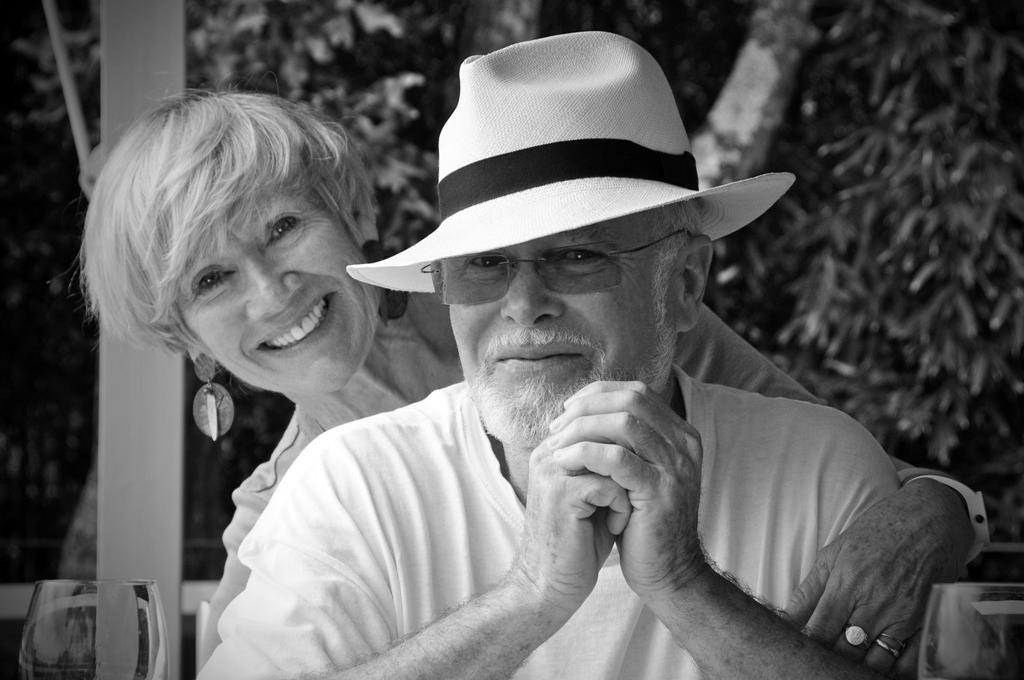

Adrian and Traudi, Palm Beach, 2012. Photo by Heidi Herbert

Adrian Boddy

For many years we have been fortunate to see and sometimes share some of the wonderful images taken by Adrian Boddy. Mr. Boddy is more than a photographer of wonderful environments and all in them though. Prior to 'retirement' he was a director at the Faculty of Design, Architecture and Building UTS, and an architectural photographer. His Master’s thesis was Max Dupain and the photography of Australian Architecture (QUT, 1996).

When and where were you born?

17th of November 1945, in Melbourne — in a thunder and lightening storm (ha ha).

Is this where you grew up?

Yes, in the south-eastern suburbs. We were the model post war, three-child nuclear family — happily housed in a new triple fronted ‘brick venerial’ with a vegie patch and chook house at the rear. I attended Chadstone Park Primary School with about sixty kids in each class; played footy and cricket at the local park; and the best thing — went for summer holidays at the beach — thanks to my grandfather who had a waterfront cottage on ‘the bay’.

Growing up — Summer holidays, Dromana, Port Phillip Bay, early 1950s (with sisters Helen and Anne)

Chadstone Park Primary School, fourth grade, front row, far right.

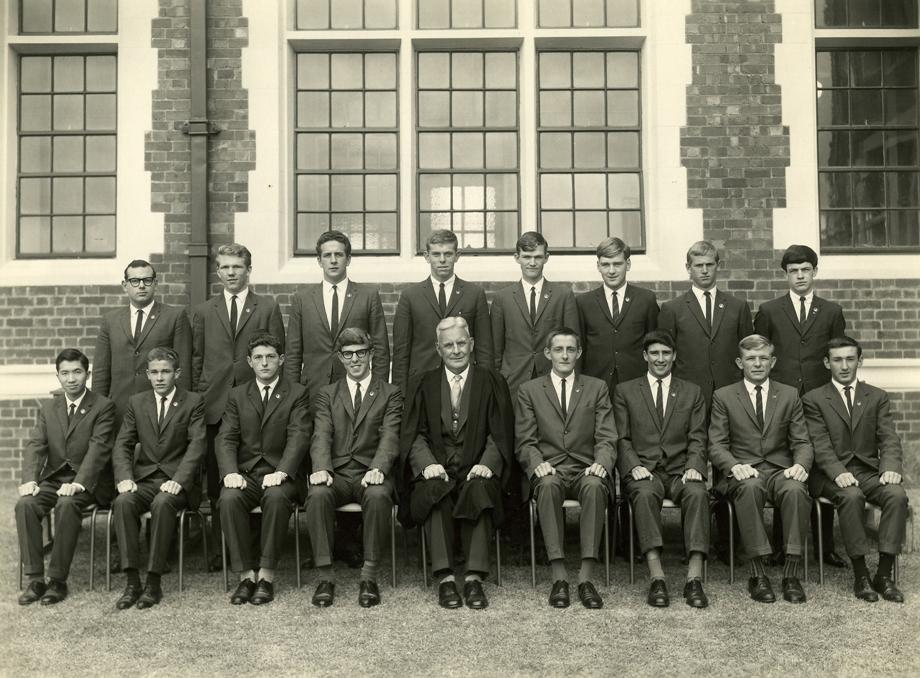

Life was very cosy, very Anglo-centric until I attended Melbourne High School — a secondary school that drew students from all over the south-eastern suburbs of Melbourne. For the first time I met Greeks and Italians and Jewish kids from Germany and Romania and the rest of war-torn Europe. That was a radical social change. School enrolments numbered one thousand across the four years preceding matriculation. The scale and depth of academic and sporting talent was initially quite intimidating. MHS was a selective high school, so students were ambitious: Ralph Dobell ran a fast 800m race around the oval — he went on to win Olympic gold; students aspired to be surgeons or chief engineers or scientists at age 15! The experience was both challenging and life changing. The school’s not-so-hidden agenda was to be better than the private schools in every way. Often it succeeded.

Matriculation prefect group, Melbourne High School — sitting, second from left.

Where did you go to university?

Melbourne University School of Architecture.

Why did you choose Architecture?

At MHS I had an Art Teacher called Jim Mollison, who later became the Director of the Australian National Gallery; he strongly suggested I study Art. But my parents, my father being a photographer, really wanted to steer me away from what they saw as a precarious existence. I had a certain aptitude for Maths in those days — used to Tutor Maths in High School — architecture just seemed a logical field of study to combine my interests – you need both those attributes when studying Architecture.

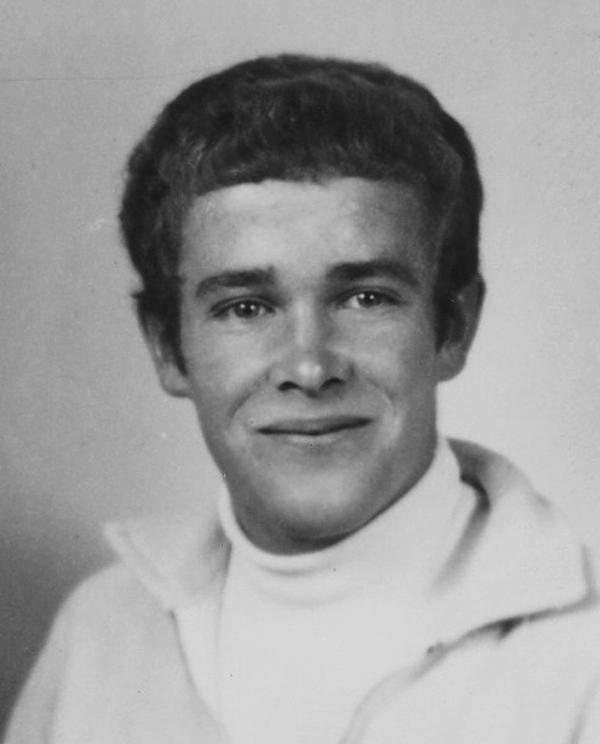

Clean-shaven and studying first year architecture. Passport photograph — Max Boddy Studio

Your father was a photographer?

Yes, my father Max Boddy was a photographer and so was my grandfather, Ernest Boddy.

What fields of photography were they working in?

They were both Studio Portrait Photographers. My grandfather was an entrepreneur; he would photograph anything! I understand that during World War II (when my dad was already serving in Darwin), my grandfather was taking photographs for Army Identification. Apparently he had a queue of young men that went around a city block. He was a skilled businessman.

My dad was a nice and intelligent bloke — denied education because of the great depression and then WW II. When I was about 11 or 12 he set up a little makeshift dark room in our laundry; and as you know, magic happens there. You never forget that moment in the glow of the yellow, orange or red safety-light, when you see an image emerge on a piece of white paper in the developer tray. That ‘magic’ never left me.

It’s not quite the same in Photoshop, but there are also some adjustments to be made in the computer that are almost magical… and so the thrill continues.

Was your mother an influence on your photography?

My mother Joan, was a petite, pretty woman and a nurse during WWII. Subsequently she became an Ikebana teacher in the Sogetsu School of flower arranging. Each week she would assemble ‘an arrangement’ made variously of fresh flowers, drift wood, rocks, sea weed… found objects. In doing so she introduced us to the importance of beauty — very often beauty in ‘ordinary’ things. ‘Composition’ is vital to Ikebana.

She also took me to the old Art Gallery of Victoria — I remember the heavy gilt frames surrounding Titian, Rubens and so on. Lots of naked ladies — a subject very interesting to small boys! I enjoyed experiencing formal art at an early age. Joan was also an avid gardener. Why am I interested in Bonsais today? The link is obvious. Clearly her influence on my photography was not specific— rather it was to do with the generic nature of beauty and that legacy is very deep and stays with you for life.

Who did you study Architecture under – who were your Professors or Teachers?

Five years is a long time to study any course at university. Lots of things happen — not all good! Here are a couple of memories…

I was at university at a liberal time — in the mid 1960s. This was the era of the Beetles, Bob Dylan, political demonstrations, surf culture… Architecture Professor Brian Lewis was famous within the sub-culture of the profession in Melbourne. If he invited you into his office you knew you were in trouble. I received a call just once! The experience was not to be repeated. Brian Lewis was also quite an entrepreneurial Professor. He had a brand new building constructed (largely through donation) just before my time. The Architecture School had moved from Nissen huts to a brand new permanent building. The building instilled confidence and pride within all of us. Recently that building was demolished and another stands in its place. Times change. There is a Brian Lewis atrium in the latest building — it’s fitting that his name lives on in the School. That is how traditions are built.

As for teachers, I had many inspiring mentors. My First Year Design Lecturer was a fellow called Hugh O’Neill. I was about three weeks into my First Year, with 150 other students, and I remember saying to him: “what do I have to do, to have a job like yours?”

He looked at me in complete dis-belief as he may have been thinking I’d said: “what do I have to do to have your job?” which is certainly not what was meant.

This is an interesting reflection because that’s exactly the direction of my career — teaching first year design. I ran first year design in New Guinea, and later, in New South Wales, for approximately twenty years.

It’s amazing how you have these moments in your life when all the planets seem to line up and you think ‘that’s what I have to do.’… more extraordinarily — you do!

Life was not always a bed of roses though.... Final Year was troublesome; we’d been required to design a high-rise housing project (twenty storeys plus) in Carlton, which meant demolishing rows and rows of terrace houses; for me this was just absurd. So I basically downed tools in Design for the first six months. A lot of parties were attended, much beer was drunk and not much thinking took place.

At this time I became aware that the Gurindji at Wave Hill Station had made hundreds of mud bricks, but they didn’t really know what to do with them. They’d acquired a mud brick-making apparatus and wanted to create their own houses. They got in touch with the N.T. Trades and Labour Council to inquire how they could utilise this new-found material. And so a bunch of students from Melbourne University flew up to Wave Hill and spent six weeks building two houses, of Gurindji Design. An escape hatch opened — it was my first excursion into self-help housing.

Returning from that experience I was on the brink of failing the year. Most of the staff showed little or no interest in our self-help housing project — other than a young Senior Lecturer, Neville Quarry, who was very interested in what we’d achieved. My final year results were mediocre to say the least. No way to graduate. Not happy parents!

That young Senior Lecturer became the first Professorship of architecture in Papua New Guinea. I heard about his promotion early in 1970 and was determined to join his staff. Things moved quickly and I soon found myself on a DC 3 winging toward the tropical town of Lae. Such was the allure of people and place, I stayed for the next five years.

When did this begin?

At the end of 1969 I left Melbourne University and within three months I was in New Guinea, Teaching Maths and Design.

Where in New Guinea were you?

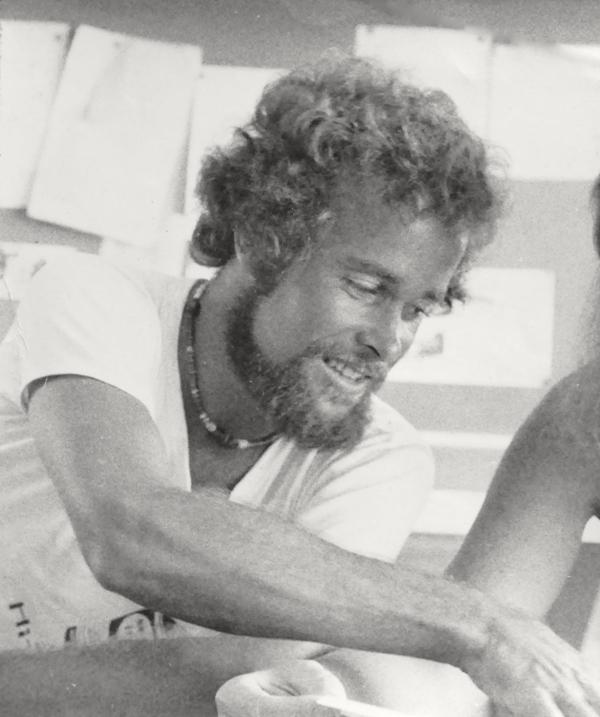

Not clean shaven; Staff meeting, PNGUT, mid 70s.

We were based in Lae (The city is known as the Garden City) at the commencement of The Papua New Guinea University of Technology. The institution was a foil, politically, to The University of Papua New Guinea (UPNG) already established in Port Moresby.

The latter incorporated Medicine, Law, Education… all the classical faculties. PNGUT’s remit was a technical emphasis: Engineering, Surveying, and Architecture.

Under Neville Quarry I had freedom to administer the First Year Program; he’d say ‘don’t bother me with the details, just go and do it’. This was real frontier stuff and it suited me as I was fundamentally suited to informal teaching, whether it was maths or architectural design.

I enjoyed five years of valuable academic experience— experience I’d never have gained in Australia.

Following my PNGUT contract I travelled around the world looking at architecture —without knowing what the next ‘chapter’ might be.

Then: Neville Quarry was in touch with me again — this time from NSWIT, where he held a new Professorship. Would I consider applying for a lectureship? I did, and secured a position that developed over the next twenty-five years or so. I owe Neville a huge debt of gratitude — for his friendship and support.

Were you still doing your wonderful photography while all this was going on?

I always enjoyed and utilised photography.

Neville Quarry was a particularly articulate fellow, and there were other academics who were also erudite. The edge that I had was working with imagery.

I could take photographs of Architecture and spin a story around that. I think, frankly, what I used to do was to conceive a lecture, and take a whole series of (slide) photographs to make the point(s). Architecture is a very visual art.

One of my well-received teaching techniques had photography at it’s very core.

Design studios and project submissions occurred on Monday nights. Of a weekend I would photograph around 30 students’ projects, whether they were drawings or models, or even written and illustrated assignments. On Monday evening, some sixty slides would be arranged in random order. Students would arrive early — in eager anticipation to review their own previous week’s work. They’d be sitting there very interested to see what everyone else had done — but also somewhat nervous that they might be the next person to speak.

I gave them only a minute or so to present; so if they spoke rubbish, everyone would know they’d spoken rubbish. I wasn’t trying to humiliate anyone, —rather the aim was to sharpen their verbal skills. It remains a positive teaching/learning experience many of the graduates still talk about.

The other aspect of photography students enjoyed followed my Study Leave, which was, frankly, an opportunity to take photographs in exotic locations.

For example, I might travel to to China, or Europe. We had quite a few Greek, Chinese and Italian students. For them to see the rich legacy of vernacular and classical Architecture projected and analysed gave them a sense of personal pride about their original homeland.

Did they incorporate these cultural influences into their work?

I think that’s a very hard matter to assert one way or the other because in the teaching of architecture in Australia, the site, the climate and the client’s requirements are paramount. In First Year students are learning about Plans and Sections, the fundamentals of Design and very often those fundamentals are abstract. They were also dealing with matters such as Architectural space, the relationship between interior and exterior. Later in the course students may have entered an international competition — set in foreign lands — and that would certainly introduce layers of cultural complexity.

What, in retrospect, are the most rewarding aspects you recall from teaching and learning?

In 1988 I was very proud to receive the university’s inaugural ‘excellence in teaching award’… it was presented at a graduation ceremony and I’d never have traded it for a promotion. In sporting terms it was a bit like winning the ‘best and fairest’.

In the mid 1990’s I received a phone call from a Prof Gordon Holden asking me to consider a secondment to Queensland University of Technology. I accepted that opportunity enthusiastically. A Senior Academic, Prof Tom Heath also agreed to supervise the Masters Thesis I wanted to write on Max Dupain, the famous Australian Architectural Photographer. Tom was a wonderful supervisor and the draft was complete by the time I returned to UTS in 1996 — it was successfully examined by Philip Cox.

So that was a real highlight.

After I retired from UTS in 2002 I received another call from Prof Holden, who was then at Victoria University in Wellington New Zealand: would I come over and mentor Design Tutors?

I said yes, I would — providing my role was teaching only — no administration, no politics.

He agreed that I could join his staff as a visiting academic to run an Elective on Architectural Photography and another on Traditional Japanese Architecture, (following student study trips to Japan). Their Design Studio wasn’t as important as I’d thought it might be. They were full-time students who enjoyed lots of studio time.

The Elective students were deeply interested and committed; it was a bit like working at a Post-Graduate level. If I have a regret it’s that I didn’t have the opportunity to engage with Post-Graduate students earlier. That’s life!

How much did the curriculum change over those 40 years?

Enormously!

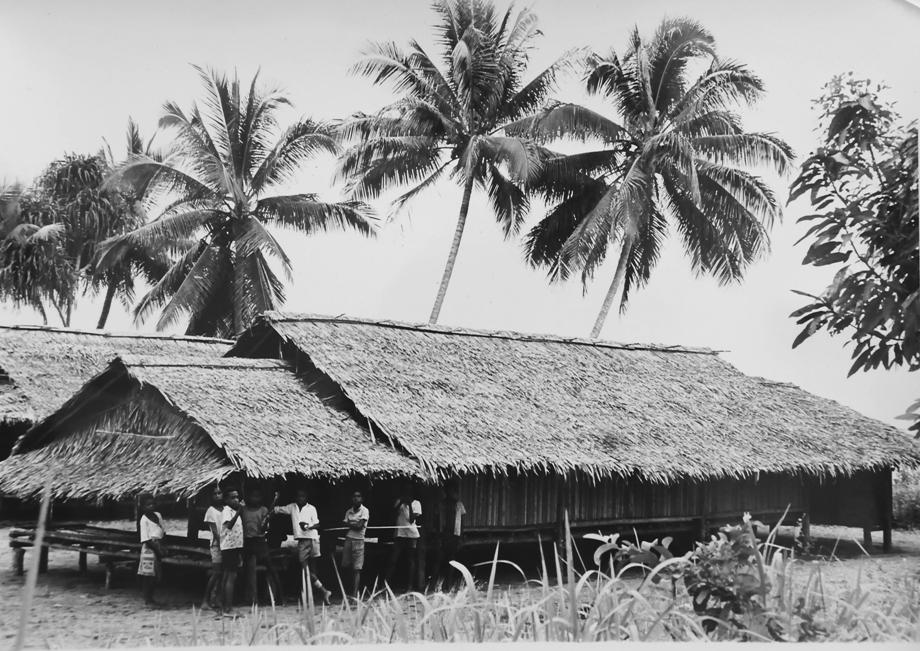

Our curriculum in New Guinea was designed specifically for Papua New Guinea Graduates – for example we didn’t dwell on the History of European Architecture, – where are the pyramids in Papua New Guinea?... They might legitimately ask. We incorporated projects such as Village Studies, where we took groups of students back to various villages and measured them up; and through interviews we established the ecology of that small place. In the fullness of time there are records of those villages – the physical layout and way of life that may no longer exist.

That curriculum received support from the Royal Australian Institute of Architects and AACA, who both had remits to assess the standards of Australasian Architecture courses.

Research photograph of Eware Village, Morobe District, 1974.

When I arrived at NSWIT (which became UTS), there was a very strong emphasis on the construction, detailing and procurement of buildings. Standards were embodied in ‘Ordinance 70’ – which was replaced by the ‘Building Code of Australia’ and I knew little or nothing about these documents — but one has to adapt to changing circumstances. These days there is an emphasis on computer-aided design. The nature of Academe is one of constant review and change. Keeps you on your toes!

How long were you in New Zealand?

There was only funding for a single semester. Traudi and I went and lived above a car park in a very questionable part of town and had a fantastic time. The students were among the very best I ever taught – as I said they were full-time. I don’t know what it is about New Zealand but they really make a great deal from very little; they’re brilliant at sustainability. Student assignments were generally of an extremely high quality, so much so I used to ask Traudi to attend their presentations. I’d sometimes give 100% — in fact I was even questioned about my assessments because they didn’t fit the standard bell curve. I said ‘bugger the bell curve; the students are outstanding – I start with 100% and work backwards; I don’t start from zero and work up.

Were there any really outstanding students or projects over the years?

Yes, we did have outstanding students, many of whom have become very successful in the profession. There are some whom I mentored towards an academic career but they were more likely to be practicing Architects or Planners.

Our design assignments generally had a technical aspect to them. I don’t believe detailing is something that happens after a concept (idea); detailing is something that happens in parallel to Design. If the detail doesn’t compliment the Design it looks like a bandaid on a beautiful face — not a pretty sight.

UTS students won lots of awards, prizes and competitions. Those results were essentially a combination of clever students having good projects to work with.

These days many of our graduates run their own businesses (I can think of one who has a staff of eighty!); many others have positions of responsibility in institutions and large companies. I know this because I continue to photograph some of their recently completed work — and this is always a particularly rewarding ‘catch up’.

Could you nominate what the unique attributes of Australian Architecture might be?

Well, it’s not so much style or fashion that interests me, it’s a combination of Modernism and Sustainability.

For example, if you have a project in Broken Hill, the climatic conditions will give rise to a very different built form should the client request the same building for Bega, or Darwin.

The Architect who made sustainability very well known to the Australian public was Glenn Murcutt, who talks passionately about the house/building as being of/in the landscape. He also speaks about the use, where possible of sustainable (often local) materials. Murcutt has an extraordinary number of international Awards to his credit. This achievement is great for him personally; it is also a recognition of high quality design and building in Australia. Young architects from countries as distant as Germany, USA and Japan travel here to see his work, and that of like-minded architects.

Murcutt’s influence goes beyond practice and publications— he has been actively teaching at all the NSW universities for decades now. There is therefore a cohort of architects who have sustainability in their DNA (so to speak) and we can be confident that the best of Australian architecture will retain a regional signature.

What are your all-time favourite buildings in the world – a classical and a contemporary example?

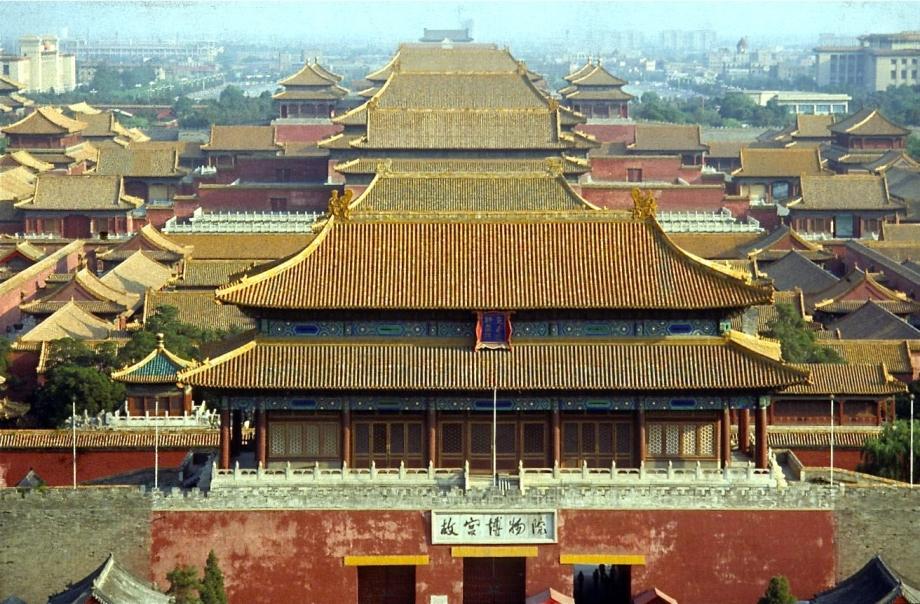

I visited China in 1973 when it was still in the throes of Cultural Revolution (1966 – 76). I was still young and very impressionable — having only lived in PNG outside of Australia. So the answer to your question has to be The Forbidden City in Beijing. You can say it is a classical assemblage of Architecture, not classical in a Greek or Roman sense, but classical in its ordering: its axis of symmetry, its orientation, its pavilion and space dialectic and in its finesse and repetition of detail, in its hierarchy – if you write down all the design principles of the Forbidden City they apply to great Architecture.

Neville Quarry, Forbidden City, Beijing, 1974 — portrait by author.

It was also constructed to conform with the underlying Chinese cultural influences —

Indeed, the philosophical principles of Confucianism and Taoism give rise to the strategic planning of the City.

That icy winter’s day with fog adding its touch of mystery to the Imperial past was certainly my most breath-taking ‘architectural moment’.

Forbidden City, Beijing, (from ‘coal hill’ or Jingshan Park) 1974.

In more recent times, undoubtedly Frank Lloyd Wright’s Kaufmann House (referred to as Fallingwater) was a ‘standout’. It is the most thrilling 20th century house I’ve ever been in. I was fortunate to visit with another of our graduate students who was studying in NYC at the time. We pressed the buzzer at around 9:00 pm just to see if anyone was there, and a fellow, who turned out to be a retired Australian actor answered.

How unusual to find an Australian at the end of a very long and rare road somewhere! He said: ‘Lads, the place is not open tomorrow – would you like to come and spend the day here?’ That was certainly a one off experience – we had hours to spend, alone, in this wonderful home — which had become a museum. We could read the Kaufmann’s books, use their FLW designed furniture, admire their sculpture and paintings and explore, on our own, the engineering and spatial complexities of one of modern architecture’s icons. Copious photographs were also taken for future teaching purposes.

Another great building, that unfortunately doesn’t photograph very well, (not all great architecture does), is the Kimbell Art Museum (1972) designed by Louis Kahn in Fort Worth, Texas. The complex is made up of a series of pavilions that have pre-stressed, vaulted, concrete roofs. The interiors glow in the most beautiful indirect light.

Kahn’s is a spare, minimal aesthetic, subsequently adopted by Japanese architects like Todao Ando — himself now world famous and whom I believe owes a lot to Louis Kahn.

Those would be three examples of outstanding architecture – a modern dwelling, a modern institutional building and an ancient Chinese city that is probably unsurpassed.

If pressed further for great moments in architecture, I’d include:

Pure Shinto: Fushimi Inari, Kyoto, Japan

Fushimi Inari, Kyoto, Japan 2009.

Perfection: Georgian town Housing: ‘The Circus’, Bath.

Sense of Place: Hydra’s harbour and surrounding houses, Home Islands, Greece.

Most hair-raising interior: The Pantheon, Rome. (2000 years old!)

Your photography – where or when did the photography of buildings begin?; the photographs you have shared with us have been wild life and landscape...

My original interest in architectural photography stems from student days. But there was a pivotal moment in 1981. The Royal Australian Institute of Architects was organising their National Conference in Singapore. They had invited a long list of International speakers. It seemed to me that there was a real chance Australian architecture could be overshadowed by their ‘foreign’ presence…. And it was ‘our show’! I suggested to the organising committee that we make an audio-visual highlighting the excellence of Australian Architecture and use this as the opening sequence? They agreed with the idea, and offered a substantial budget. Never having made an AV show presented some considerable challenges — my method was entirely intuitive. A ‘story of Australian architecture’ was sketched; lots of buildings were photographed; music was composed by NSW Conservatorium students; a primitive computer recorded pulses to dissolve images on four slide projectors. In Singapore a twenty foot long screen was constructed. The ‘show’ titled: Images of Australian Architecture’ lasted 11 minutes AND mercifully it worked – it was a bit of a cliff hanger for me as the pulses weren’t quite right and it could have resulted in a giant stuff-up. At the end of the presentation to five hundred architects, Harry Seidler said to me ‘son, you’ve made me proud to be an Australian’.

I thought, ‘I’ve done it’… as Harry was a well known tough task-master. From that single event I received commissions from Architects to photograph their work. Subsequently I photographed architecture in parallel to my academic life and this enabled me to bring examples of contemporary Australian Architecture into the Design Studio. For quite a while I was only photographing Architecture and student work.

How did that chicane into all those wonderful images of birds though – or those misty mornings among Palm Beach Trees?

A diversity of subject matter probably relates back to my family background. Photographers often specialise in a particular subject, but this doesn’t preclude other visual opportunities.

My recent exhibition on Japan was mostly a selection of Portraits, which is what my dad and my grandfather did. (They would probably be turning in their graves if they thought I’d become a Portrait Photographer).

What’s the difference between taking a photograph that’s a Portrait and one that is of a building?

Technically there’s a lot of difference.

With a building you’re concerned about the geometric precision of the subject. Verticals must be vertical etc. — you’re also concerned about a maximum depth of field. The most important task of the architectural photographer is to conveying something of the Design sensibility of the building — very precisely — there is nothing spontaneous about the discipline.

With Portraits a narrow depth of field is quite helpful because, as my grandfather said ‘for a Portrait, frankly Adrian, all that needs to be sharp are the eyes – that’s what people look at’… a somewhat over-simplified comment with a grain of truth. It has been said that taking good portraits is like swatting flies — you have to be fast and accurate — seize the moment so to speak.

Buildings might not move but they are subject to changing weather conditions. ‘Follow the Sun’ might be the photographer’s motto — certainly their method.

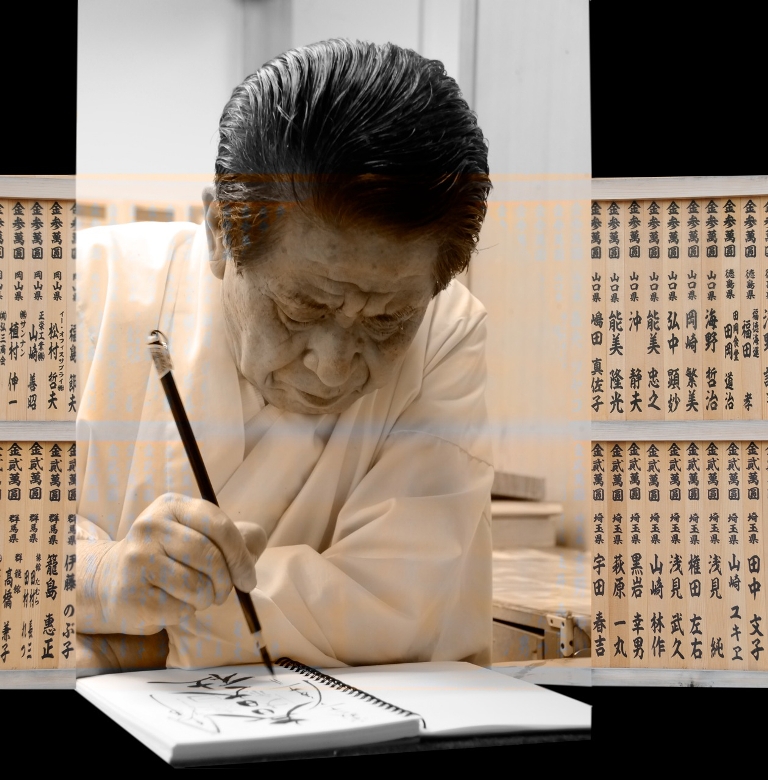

But this gentleman here (‘The Calligrapher’), my favourite from your recent Exhibition, he’s not looking at the camera, he’s immersed in his work and this conveys something else…he’s not posing…

‘The Calligrapher’ Nara, Japan, 2009

Yes, it’s an off-camera image. Often you will find that the posed photo has a kind of dumb simplicity about it; ‘stand over there and let me take your picture’. What’s amusing about this picture (Two Geiko, Kyoto), and what interests me, and interested almost everyone who visited the Exhibition, was the contrast between the look of calm understanding on one woman’s face compared with the other who has turned her lip down suggesting: ‘when are you going to finish?’ – that’s hilarious. She’s fed up and she wants to move on.

Two Geiko, Kyoto, Japan 2009

So for Portraits, a narrow depth of field and get close to your subject. Very often the most successful ones are off-camera.

What are your favourite photographs?

I couldn’t say – there are too many… the cheeky answer would be; the next one.

How many have you taken?

Maybe a couple of hundred thousand.

How many Exhibitions have you been a part of now?

Not so many.

Most recently I participated in the Head On Photo Festival at the Willoughby Incinerator Art Space – prior to that (2013) was a celebration of Walter Burleigh Griffin at the same gallery.

From: ‘Japan: Australian Perspectives’, Incinerator Art Space, Willoughby 2015

From: ‘A Celebration of Walter Burley Griffin’, Incinerator Art Space, Willoughby 2013.

In 2000 there was a competition/exhibition at UTS called ‘Techne’ which was to be ‘a fusion of Art and Technology’. For this I used a motherboard from an old computer as an abstract modern city. Then I ‘set fire’ to it; immersed it in bubbles — then sand, I photographed a whole range of iterations of urban decay and titled the series: ‘Silicon City Unplugged’ Luckily I won that competition.

What was the prize - a bottle of wine?

No, a couple of thousand dollars… so it was worth entering ha ha.

There was also a photography competition at Melbourne University when I was a student – and I won that too.

I find it difficult to judge photography, so participating in competitions seems a bit strange.

Most of my photography is either for personal satisfaction or for a client’s need.

One of the great thrills of doing what I do is that I get to catch up with Graduates – many of whom are now in their 60’s. I meet their families, take Portraits of their kids, have dinner with them – this is what life is about. Just recently we stayed at Thredbo in a building designed by a Graduate, owned by another, and while there, was emailing yet another graduate in Korea. My life is very much tied up with UTS graduates.

Riverside Apartments, Thredbo Village, NSW. Design: Robin Dyke, 1990s

Where did you meet Traudi?

At NSWIT. It took several years for us to be together. I remember saying to her at a faculty party, ‘when you’re tired of your current man, let me know and I’ll take care of you’.

We lived in Redfern to begin with — prior to buying the weekender at Palm Beach.

The Palm Beach weekender was Traudi’s initiative and was all about having access to fresh air, going swimming and relaxing. The house in Redfern was a seven-minute walk to work but gradually Palm Beach became our home. Suddenly commuting was two hours per day. Pittwater must have been worth it!

We loved our little cottage and the beautiful tropical garden we created. Never thought we’d leave, but thirty something steps to the front door can present problems. Avalon Parade is now home — and we haven’t missed a beat.

Who are your favourite photographers – clearly Max Dupain is among these?

Yes, Max Dupain is a standout in the field of Australian Photography and Australian Architectural photography.

You know his family had a place at Newport?

Yes – I know almost everything about Max Dupain, I ‘lived’ with him for many years ha ha.

Oh yes, the Thesis!

Dupain is one of my favourites because in his day, he was the outstanding Architectural photographer in the country — along with one other person – Wolfgang Sievers. Sievers was a Jewish émigré who settled in Melbourne during WWII. A simple commercial divide existed: Sievers ‘had’ the Melbourne clients; so he photographed the ICI Building and the work of cutting edge firms such as Grounds Romberg and Boyd. Dupain ‘had’ Sydney architects including and most notably Harry Seidler. These were simpler times, There wasn’t a hell of a lot of competition.

Now everyone thinks they’re a photographer and with the advances in technology one doesn’t have to carry around massive film cameras that you need a licence to operate.

Digital cameras are convenient— but they too have their limitations.

Who is your favourite Art Photographer?

I have a library full of books –but I’m thinking Sebastiao Salgado. Of course he’s technically brilliant but he always had a conscience about his work. He has worked in the mines in South America capturing images of thousands of workers teetering on bamboo ladders — hugely dangerous in a really toxic environment. His photographs brought the appalling conditions of these workers to the attention of the world. This is fundamentally very very important.

Then Salgado became interested in remote communities and photographed Africans and Indians ands these are just the most amazing images into both Nature and Humanity.

He is such a deeply humane person… who is concerned about the future of the planet.

In recent times I would say I was very fortunate, no, privileged, to meet a young Columbian photographer called Erica Diettes.

I had written a piece for the catalogue of the Ballarat International Foto Biennale 2013 and said to Traudi – why don’t we drive down and have a look?

Erica had some fifty portraits printed on silk — each was approximately a metre square, some even larger. The subjects were women with anguished faces. They were all Columbian women whose husbands, boyfriends, sons or brothers had been murdered by the drug dealers/cartels.

She had her work displayed at various heights, both vertically and horizontally, in the Mining Exchange Building, which is a vast cathedral-like space so you could see through the pictures – they were diaphanous and moved. The figures had a life about them, a tormented tortured life.

Sudarios, Ballarat Foto Biennale, Victoria, 2013

I said to Erica: ‘this is probably the most profound exhibition I’ve ever been to in my life’. She continues to work on this theme in various countries – and has been recognised in America, also in Australia — if not adequately.

I would like to see the Museum of Contemporary Art exhibit her work, as domestic violence is still a very big issue here. Although her subject isn’t exactly domestic violence, it is institutional violence conducted in the domestic domain. In some instances, the drug dealers would murder the husband, brother, son, boyfriend, in front of the woman. This is classic medieval criminal behaviour that terrifies the individual, the town, the village — the whole country into silence.

Erica is a beautiful woman sticking her neck out, endangering her own life for this important cause. I admire her so much: for her courage; for her artistry; for her humanity.

We saw her again in Sydney and retain a long-distance friendship.

So those are three photographers: Erica Diettes and Sabastiao Salgado continue to use the camera for very specific social/ethical and aesthetic ends. Ends that I regard as fundamentally important. Max Dupain, is included because he conveyed the art of Australian Architecture to our broader community.

In speaking of your favourite photographers there’s a theme about the human condition – what do you think being a photographer all of your life has given to you?

Quite a number of things. When I was running Photography Electives I used to say to the students ‘I really hope for one thing; that you will see the world differently as a result of this Elective – I don’t mind how you see it, as long as you see it differently’.

I said that to them because that’s what photography has done for me — with thanks in particular to my parents. Photography has also enabled me to have a very successful academic career; successful in terms of inspiring students. Thirdly, beauty is important to me — and photography is a discipline that distils beauty in two dimensions.

What a very fortunate life you have had so far.

Yes, I heard Dick Smith say recently, on being awarded an OAM, that he was very fortunate to have been born in Australia in the 1940’s. I couldn’t agree more. To be born in Melbourne in the 1940’s was so gentle, it was like riding a wave – no one was dropping in on you and there was clear water ahead. After WWII there were many educational programs including Commonwealth Government scholarships and cadetships. Without my Commonwealth scholarship I would not have been able to afford a tertiary education. Life would have been very different indeed. .

They had to rebuild a nation?

Yes, from the ground up. The federal government also instigated the Colombo Plan which was very, very clever. This program enabled high achieving students from India, Ceylon, Malaysia, Singapore and Hong Kong to come and study at Australian universities. We therefore had some of the highest calibre Asian students working and studying alongside us at Melbourne University.

So what Government had done through this program was make a commitment to rebuild the whole region then?

That’s correct – in some ways it was an ingenious political strategy but it also began establishing something else — it built fondness for Australia in Asia. I recently received an Alumni Magazine from Melbourne University in which they published a report about their new building. I mentioned this earlier, and there’s a list of Donors towards this project.

I haven’t counted the number of Asian donors but they must be at least 70% of those who have contributed. To me this indicates that they are incredibly grateful; have become successful — and now want to give something back.

What is you favourite place in Pittwater and why?

The McKay Reserve – particularly accessed from the corner of Ebor and Cynthia Roads. One walks through a cathedral of wonderful angophora and scribbly gum trees to a rocky outcrop that affords a panoramic view of Pittwater. In fog it becomes a mystical place – you just know aborigines must have gathered there and to eat their seafood.

We were also very fond of our own little cottage. It seemed to recognise the virtues of the old Palm Beach: the sandstone chimney, the wooden floorboards, weatherboards and the fact that it was so tiny, on a large block of land, hidden away form the street – most people didn’t even know it was there.

I suppose Barrenjoey Headland would be common answer? When you arrive at the top you realise it’s a truly unique place; the sandstone residential buildings are very beautiful, and the lighthouse is amazing for its craftsmanship of both metal, glass and stone – but keep walking; go right out to the very end where the headland becomes precipitous and a bit scary; that to me is fantastic.

View north from Barrenjoey Headland, July 2005

Lighthouse detail, Barrenjoey Headland, January 2010

Kuring-Gai Chase has many wonders too, including wild life, flowers, magical panoramic views and sacred aboriginal places — all within forty kilometres of Sydney’s CBD. Hard to beat that!

What is your motto for life, or a favourite phrase you try to live by?

I don’t have a motto, but when I retired, some funny students posted: “Adrian Boddy: Architect who Retires Without Plans” — I thought that was hilarious, as well as true. I like the possibility of making space for the unknown; allowing time for unplanned events to just unfold. ‘Don’t over-plan life’ might suffice as a motto.

McKay Reserve, August 2007

Pittwater and Kuring-Gai Chase from Palm Beach, March 2012

Copyright Adrian Boddy, 2015.