June 10 - 16, 2012: Issue 62

Obverse of the silver commemorative medal.

Reverse of the bronze commemorative medal.

Bicentenary limited edition Royal Doulton Bicentenary plate showing the ships of the First Fleet

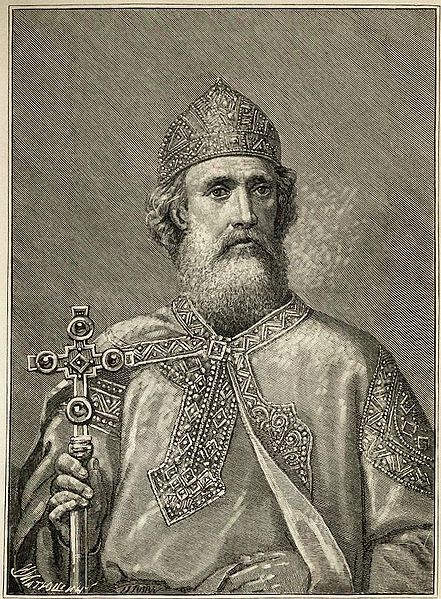

Vladimir I of Kiev, Engraving circa 1889

View of the Trinity-St.Sergius Lavra from outside

Images of medals, plate and View of the Trinity are by George Repin. Andrei Rublov's Holy Trinity Icon in the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow from and courtesy of the Tretyakov gallery website.

A MILLENIUM APART

By George Repin

In 1988, the year in which Australia celebrated the Bicentennial of European settlement, the Diocese of Australia and New Zealand of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad linked this event with another dating back 1,000 years. In 988, following the baptism of Vladimir, Prince of Kiev, Christianity was accepted as the state religion of Kievan Rus and subsequently of Russia. Despite the efforts of the Soviet state to suppress religious expression, at best by discouragement and at worst by persecution, today Russians have flocked back to religious expression and many, not just the old but also young people, are filling the churches.

To mark the Millennium the local Diocese of the Church struck a commemorative medal. The obverse carries an image of St Vladimir and the dates 988-1988. The reverse shows a sailing ship set on a map of Australia and the dates 1788-1988 to mark the Australian Bicentenary. On each face the legend is in both English and Russian. The medal was struck in limited editions of 300 in bronze and only 40 in silver.

The celebration of the Millennium and the resurgence of Christianity in Eastern Europe have been accompanied by a renewed interest in the art of iconography. Historically, religious icon painting, the Christian art of Asia, Eastern Europe and Russia, dates from the mid 3rd Century although it is said that icons existed before that time. An icon is an image, a picture or a likeness – but in the religious context the word denotes a portable religious picture.

Icons take a variety of forms and, over the centuries, different

schools of iconography have developed. Some outstanding icon painters (such as

Andrei Rublev 1360-1430) have been recognised for the extraordinary quality of

their work which can be seen both in churches and in gallery collections.

Rublev is considered by many to have been the greatest medieval Russian painter

of Orthodox icons and frescoes. In 1425-1427 he and Daniil Cherni painted the

Cathedral of St. Trinity in the Trinity-St.Sergius Lavra in the so-called

“Golden Ring” outside Moscow. The only work ?

![]()

Andrei Rublov's Holy Trinity Icon in the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow from and courtesy of the Tretyakov gallery website.

From March to October 1992 Australians had the rare opportunity to see beautiful icons included in the exhibition of Secret Treasures of Russia from the State History Museum of Moscow, arranged by Art Exhibitions Australia – an exhibition indemnified by the Australian Government.

There are icons in private collections in Australia brought by migrants, particularly by Russians who fled China after 1949 when Mao Zedong came to power. Many of these refugees sold their icons, which were for them “portable” valuables, on their arrival in Australia to release funds – in many cases for much less than their worth today.

One private collection, which residents of Sydney had the unique opportunity to see in the Chapter Hall Museum of St Mary’s Cathedral from April 30 to October, 30 1991, was that of the late Mr Jacques Cadry whose interest in icons started when he was a schoolboy in Paris and was rekindled in Teheran where, in the 1930s, he started to collect icons.

Note: The Millenium Monument in Novgorod (pictured) marks a

different millennium. It was erected in 1862 to celebrate Rur

Copyright George Repin, 2012. All Rights Reserved.