Science Week 2021: Take a coastal Rock Platform Pool Tour to see what's in the sea - for youngsters

We've put some great stuff on offer for you to do this week, Science Week, in your page this Issue, some of which can be done in your own backyard. Your teachers will have great lessons and stories for you too - for sure.

Science Week reminded me that a few years ago we took a Coastal Platform Tour organised by the Learn2Swim program at Narrabeen Rockpool and how much enjoyment my brothers and I used to get exploring those rock pools beside the beaches or along the shores of the bays. Seeing crabs, sea anemones, starfish - all kinds of small and wondrous sea creatures was great fun and hearing about what they did and how they eat or are food for other sea creatures was very interesting.

As you and your mum and dad may like to do one of these as an outdoor exercise this week, we thought we'd put together some of the great creatures we found out about then, along with others some of the great people who help put the PON together have sent in - we all seemed to have had the same idea at the same time.

There's also some great pictures and explanations about these sea creatures here, so you can 'meet some of the other locals' on our shores and in our aquatic reserves. The only thing you need to be careful about is listening to mum and dad when in these places as, even though they'll probably choose to go at low tide there can still be waves or slippery parts, putting these creatures back into the water where you find them if you want to pick them up to have a closer look, and wetting your hands before you do as this makes it 'gentler' for those sea creatures themselves.

There's also some more 'sea stuff' at the base of this page for you to read and look at too.

Ok - here we go:

Sea Snails: same as garden snails almost; they are herbivores; eat algae and the beautiful patterns of their tracks we see in the sand that gathers on the rocks is their movement in search of this food. This is what they look like:

Above - Sea snail track Patterns

Sea Stars: camouflage themselves by becoming same colour as rocks they are on. Will also ‘grab a lift’ off the sea snails by attaching themselves as snails are faster then them. This is what they look like:

Sea anemone: these felt a bit slimy and soft in places. This what they look like:

Starfish; can flip over as has all these legs when we put them on their backs; eating a bit of octopus in this photo. A 'flip back over demonstration' by Sally and one that was bright red-orange:

Chiton: has an articulated shell. They are small to large marine molluscs, and are sometimes called 'sea cradles' or 'coat of mail shells. “Looks like a cockroach!” said one of the children. This is what they look like:

Clam: a burrowing bivalve of the mollusc family. This is what they look like:

Elephants snail (mollusc): named for the way they swing their tentacles from side to side; This is what they look like from on top and from underneath:

Sea Hare (Hairy Sea Slug): they have a soft body, a small internal shell and large 'wings' or parapodia, which can be used for swimming. They too are molluscs. This is what they look like out of and in the water:

While handling these molluscs without shells Sally said: “wet your hands first and then you won't hurt them. They live in the water and get sick if out of it too long"

Sea Squirts or Congee boys: prehistoric, very important to the rock platform as they are filter feeders and clean everything up. You can see them squirting like fountains in rows off the rock shelf where it meets the sea. Important not to squeeze them and make them spurt as they are storing water for low tides. They are chordates; like us! This is what they look like:

Sea scallops: are in the mollusc group called 'bivalves'. The name "scallop" is derived from the Old French escalope, which means "shell". This is what they look like:

Periwinkles: these are a small edible sea snail, a marine gastropod mollusc that has gills and an operculum and have dark or black coloured shells. This is what they look like:

Neptune’s Necklace (sea plants): like all plants, even sea ones, they need sunlight to photosynthesise and this is why you find no plants in the depths of the ocean and why these ones are so close to the saltwater’s surface.

Sea Kelp: grows off the rock shelf; the spikes are ‘shock absorbers’ to help it not bump too violently and damage itself. It has a mucus component which protects ot from the sun, like a built in sun block. Here Sally is holding one up for the children to feel its textures:

Conniwinks Shells and eggs. (Sally was down here two weeks ago and there were masses of them filling all the crevices on the rock shelf). The shell here has a few 'freeloaders' catching a faster ride;

Cowrie shell: some cultures use these for money, also attractive to sea shell collectors but must be put back when found in an Aquatic Reserve.

Skin of an octopus shed; until held this looked similar to a piece of plastic discarded by a litterbug.

Holdfast; (sea plants: which to the girl who brought it to Sally to be identified and named was “Like a lollipop”: they are the rootlike structure that some plants and algae use to attach themselves to sea rockshelfs.

Zebra Snails have a black-and-white striped pattern on the shell.

Limpet with barnacles on it: Limpets are a marine gastropod mollusc that has a low conical shell. Barnacles on top are are marine and estuarine crustaceans and related to crabs!

Walking anemone - photo by Selena Griffith:

Walking anemone closed - photo by Selena Griffith:

Waratah anemone - photo by Selena Griffith:

Urchin - photo by Selena Griffith:

Nudibranch - photo by Selena Griffith:

A nudibranch - this one is often called an Elephant Slug, with a Chiton passing underneath it (lower right of picture) - photo by Selena Griffith. Nudibranchs' are carnivorous, so they eat sponges, coral, anemones, hydroids, barnacles, fish eggs, sea slugs, and other nudibranchs:

Sea hare - photo by Selena Griffith:

Starfish - photo by Selena Griffith:

Sydney seastar - photo by Selena Griffith. More on these here (there's a few !): australian.museum/learn/animals/sea-stars/sydney-seastars

Sydney seastar- photo by Selena Griffith - Selena says; '9 legs on this guy - most of the others only had 4 !! He’s a hoarder!':

Brittle star babies - photo by Selena Griffith:

Baby fish - maybe a rockfish - photo by Selena Griffith (Selena put it back in the water):

Slate Pencil Urchin- photo by Selena Griffith - The Slate Pencil Urchin is a herbivore. It comes out to feed at night. The mouth is on the underside of the body and is equipped with five sharp teeth used to scrape algae from the rocks.:

Narrabeen's Octopus

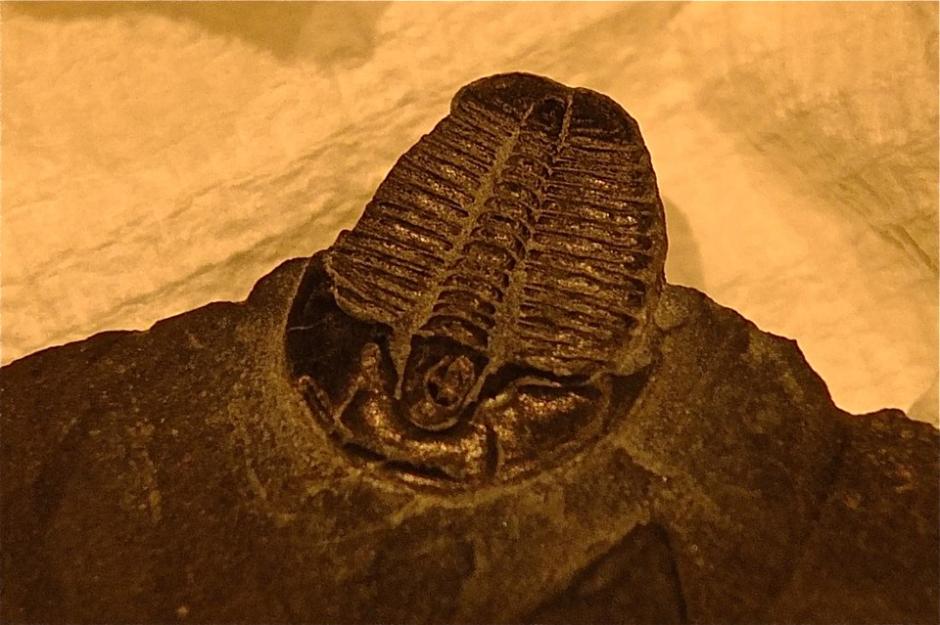

Fossil at Avalon Beach

Found by our intrepid three year old fossil-cker!

Curious Kids: why are some shells smooth and some shells corrugated?

This a piece from Curious Kids, a new series for children. The Conversation is asking kids to send in questions they’d like an expert to answer. All questions are welcome – serious, weird or wacky! Email your question to curiouskids@theconversation.edu.au

Why are some shells smooth and why do others have a corrugated shell? – Maëlle, 7, Cebu City, Philippines.

What an interesting question! There are a few possible answers.

Squishy, soft-bodied animals like pipis, oysters, mussels and scallops live inside shells.

A lot of animals (including many humans) think these shellfish are pretty tasty, so they need shells to protect them from hunters who want to eat them.

Some fish can pick up the shell in their mouths and smash it open against a rock. Other animals, like octopuses and snails, can drill a hole into the shell and inject poison that can kill and digest the animal that lives inside.

They then suck the digested animal out through the hole they drilled, much like you might suck up a drink through a straw. Having a strong shell may help protect the mollusc living in the shell from these kinds of attack.

It is possible that the corrugations may help strengthen these shells. Have you ever seen a corrugated iron roof on a house? Corrugating it strengthens the iron and makes the roof stronger. Scientists think perhaps that is also true for corrugated shells.

Scallops have a fan-shaped corrugated shell which is hard to break, even if you drop it or hit it. These corrugations are called ribs and provide scallops with strong and rather heavy shells.

The corrugations may also help with camouflage. Other animals and plants can grow on their shells, making the scallops masters of disguise! But when camouflage does not work, scallops can swim in a clumsy way by opening and closing their valves quickly.

Giant clams do not move or dig themselves into the sand. Their main strategy for protection is to grow super strong, thick and heavy shells and, as you can see, these also have corrugations. Giant clams are the largest clams in the world. They can reach up to 1.2 metres in length (around the height of a six-year-old kid!), weight more than 200 kilograms and can live for more than 100 years.

The animals that have smooth shells use a different approach to protect themselves from other animals. They can move away quickly and dig themselves into the sand really fast! It is like sliding in the playground; having a smooth shell would make it easier for these animals to move more quickly, just like a smooth slide would let you go faster than a bumpy slide.

Look how fast this pipi can dig down!

Clams with smooth shells (including pipis) can dig themselves into the sand in just a few seconds! They use their foot (which looks more like a tongue) for digging. And they use their long siphon to breathe when burrowed, much like you would use a snorkel to breathe when you are underwater.

This way, they are protected but are still able to feed and breathe.

Animals can use many different strategies to protect themselves. It is likely that many of these animals evolved to have different types of shells that are good – in different ways – at keeping the squishy animals inside safe and sound.

Hello, curious kids! Have you got a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to us. They can:

* Email your question to curiouskids@theconversation.edu.au

* Tell us on Twitter by tagging @ConversationEDU with the hashtag #curiouskids, or

* Tell us on Facebook

Please tell us your name, age and the city you live in. Send as many questions as you like! We won’t be able to answer every question but we will do our best.![]()

Jan Strugnell, Associate Professor Marine Biology and Aquaculture, James Cook University and Catarina Silva, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, James Cook University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Curious Kids: Is it true that male seahorses give birth?

This is an article from Curious Kids, a series for children. The Conversation is asking kids to send in questions they’d like an expert to answer. All questions are welcome – serious, weird or wacky!

Is it true that with seahorses, males give birth? - JJ, age 9, Brisbane.

Great question! It sounds crazy, but it is true.

Seahorses and their close relatives the pipefish and the seadragons are very unusual, because it is the males that get pregnant and give birth to the babies. Instead of growing the baby seahorses inside their belly in a uterus, like human mums do, the seahorse dads will carry the babies in a pouch, a bit like a kangaroo’s pouch.

To produce babies, seahorses have to mate first. Seahorse mating is really beautiful. Males and females dance around one another and flutter their fins, and they may dance together over several days before they actually mate.

When they’ve decided they like each other, the seahorse females swim towards the surface of the water, and the males follow. The females then put their bright orange eggs into the pouch of the males through the hole at the top of the pouch. Once the eggs are safely inside, the males will add their sperm and shut the opening. The eggs are fertilised by the sperm, and then start developing into baby seahorses.

With that, the job of the seahorse mum is done! She swims off, and leaves the father to take care of the growing babies. Inside the pouch, the babies grow eyes, tiny snouts, and little tails. It takes about 20 days for the babies to develop, safely tucked away from other animals that might want to eat them.

It’s tough being a baby seahorse

When male seahorses give birth, it is very dramatic. You can watch a cool video of seahorse birth here:

The male will open the hole in his brood pouch, and violently jerk around to squeeze all of the babies out. They shoot out very quickly, and it looks spectacular. In fact, some species of seahorse can give birth to more than 1,000 babies at once!

After he has given birth, the seahorse dad does nothing more for his babies. They must look after themselves and hide from predators, as they have no parents to protect them. The seahorse father does not eat until several hours after he has given birth. However, if the babies are still hanging around him after that, they may become a tasty meal. That’s right, males sometimes eat their own babies.

It’s tough being a baby seahorse. Of the hundreds of babies that the male gives birth to, only one or two will survive to become adults and have babies of their own.

Hello, curious kids! Have you got a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to us. They can:

* Email your question to curiouskids@theconversation.edu.au

* Tell us on Twitter by tagging @ConversationEDU with the hashtag #curiouskids, or

* Tell us on Facebook

Please tell us your name, age, and which city you live in. You can send an audio recording of your question too, if you want. Send as many questions as you like! We won’t be able to answer every question but we will do our best.![]()

Camilla Whittington, Research Fellow / Lecturer, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.