Safeguard Mechanism legislation: Dr. Scamps' Amendments

The Safeguard Mechanisms (Crediting) Amendment Bill 2022 seeks to amend the National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting Act 2007 and Australian National Registry of Emissions Units Act 2011 to enable the trading of Safeguard Mechanism Credits (SMCs).

Independent MP Dr Sophie Scamps moved amendments to the Safeguard Mechanism legislation that aim to impose stringent limits on new fossil fuel projects and guarantee real emissions cuts.

The amendments will seek to ensure all new, expanded, or extended fossil fuel facilities to have net zero carbon emissions at commencement, and for the life of the facility.

Another amendment to be moved by Dr Scamps will aim to guarantee the integrity of climate and carbon market related bodies such as the Climate Change Authority by ensuring appointments to those bodies are independent from government.

Dr Scamps, MP for Mackellar has stated,

''The safeguard mechanism must be a success for Australia to reach our 43% emissions reduction target by 2030. The collaborative nature in which the Minister has engaged with me and my crossbench colleagues on potential reforms has been welcome.

However, I have some serious concerns about the safeguard mechanism as currently proposed as it does more to safeguard the future of the fossil fuel industry than it does to safeguard the future of our climate.

Under the proposed model, facilities can meet their emissions reduction targets entirely with the purchase of offsets. There is no real abatement requirement. The only other jurisdiction that allows unlimited use of offsets is Kazakhstan.

The scheme also only deals with scope 1 emissions, that is, only those emissions that result from the production of the commodity. It does not deal with scope 3 emissions, such as when coal is burnt, which are the biggest threat to our climate. Additionally, fossil fuel facilities – existing and proposed – are treated no differently to other participants in the scheme, even though we know they are the worst of the worst offenders on climate change. It is also still unclear how new entrants to the scheme will be treated: what will their obligations be? What does the government mean it refers to ‘international best practice’?

There is serious doubt over whether the proposed changes will lead to real emissions cuts.

To that end, I will be moving amendments to the Bill which are designed to impose stringent limits on new fossil fuel entrants.

My amendments will require all new, expanded, or extended fossil fuel facilities to have net zero carbon emissions at commencement, and for the life of the facility. In this scenario:

- a new gas project would be required to enter the safeguard mechanism at net zero, and stay there for its operational life

- a coal mine seeking to expand the area of its mining operations would need to ensure the expanded area operates carbon neutrally and remain that way for its operational life

- a company seeking to extend the life of a coal seam gas project would need to ensure the project is net zero from the day of the project’s extension and stay there for its operational life.

In addition, I am also moving amendments that seek to guarantee the integrity of climate and carbon market related bodies such as the Climate Change Authority and the Clean Energy Regulator, by guaranteeing the independence of appointments to those bodies.

These amendments are modelled on the best practice process outlined in my ‘Ending Jobs for Mates’ Bill – which the government should back, to ensure we can trust all decisions made by important institutions such as the Climate Change Authority.

Australians voted for real and urgent climate action at the last election, and the people of Mackellar have told me that climate change is the number one issue they want me to address as their MP. The changes I am requesting today will go some way to ensuring the safeguard mechanism does exactly what it should – reduce emissions from some of Australia’s biggest polluters.''

The Climate Change Authority is an independent statutory body established under the Climate Change Authority Act 2011 to provide expert advice to the Australian Government on climate change policy.

The Authority plays an important role in the governance of Australia's climate change mitigation policies including by providing independent advice on the preparation of the Annual Climate Change Statement to Parliament; and greenhouse gas emissions reduction targets to be included in new or adjusted nationally determined contributions (NDC).

The Authority also undertakes reviews and makes recommendations on the Carbon Farming Initiative (Emissions Reduction Fund), the National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting System, including the Safeguard Mechanism and other matters as requested by the Minister responsible for climate change or the Australian Parliament.

The Authority conducts and commissions its own independent research and analysis. All reviews include public consultation and all reports will be published on the Authority's web site after they have been given to the Minister.

The Authority is made up of a Chair, the Chief Scientist and up to seven other members.

On March 8, 2023 the Climate Change Authority made a submission in response to The Treasury’s climate-related financial disclosure consultation paper. The consultation paper seeks views on key considerations for the design and implementation of standardised, internationally‑aligned requirements for disclosure of climate‑related financial risks and opportunities in Australia.

The Authority’s submission aligns with its views on the need for companies to identify and manage climate-related risks and that the adoption of net zero emissions reduction targets in the corporate sector should be backed by detailed, practical plans outlining how net zero targets will be achieved.

Specifically, investors and the broader community should be informed of the investment decisions companies are intending to make in new, low and zero emitting production processes, when these technologies will be implemented in production systems, and the volume and type of offsets, if any, being included in plans to deliver on emissions reduction commitments.

You can view the Authority’s submissions here.

To Question 2: Should Australia adopt a phased approach to climate disclosure, with the first report for initially covered entities being financial year 2024-25? and 2.1 What considerations should apply to determining the cohorts covered in subsequent phases of mandatory disclosure, and the timing of future phases? - the Authority stated:

A phased approach to implementing compulsory climate disclosure, covering larger entities first, is a sensible approach. A plan for the first reporting year of the Australian climate-disclosure framework to be 2024-25 is a practical step, however, it is noteworthy that these reports are not likely to be published until late 2025, only 5 years before the end of the 2030 target period.

The approach used to select entities to be included in subsequent cohorts should ensure that all listed companies who own or have a financial interest in a facility covered by the Safeguard Mechanism, including companies who own or have a controlling financial interest in fossil fuelbased electricity power stations, report under the climate disclosure framework.

In subsequent years this could be widened so that all listed companies which own or have a controlling financial interest in a facility which exceeds the emissions reporting threshold under the National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting (NGER) scheme also report under these arrangements.

The Government should also consider how entities that are not listed companies, but which trigger the Safeguard threshold and subsequently NGERs emissions threshold for reporting, can also be required to make climate disclosures. We welcome the Government’s commitment that comparable Commonwealth entities will also disclose their exposure to climate-related risk.

Bringing all these entities into the climate reporting system will build on the information that is available on the emissions of these entities to inform investors and the community of the practical and specific emissions reduction plans of these entities.

The climate disclosure framework may result in multiple companies reporting emissions from the same facilities. This would not be a deficiency of the scheme. The purpose of the climate-risk disclosure framework is to inform investors and the community of the climate-risk exposure of Australian companies rather than to provide the basis for an inventory of Australia’s industrial sector greenhouse gas emissions. The NGER scheme already fulfils this role.

Question 11: What considerations should apply to ensure covered entities provide transparent information about how they are managing climate related risks, including what transition plans they have in place and any use of greenhouse gas emissions offsets to meet their published targets?

Climate Authority's Answer:

This is a key concern for the Authority. Australia’s transition to net zero emissions will require actions by the owners and managers of large emitting facilities in Australia to reduce their emissions.

The Authority welcomes announcements of emissions reduction and net zero targets by Australian entities. These announcements are an encouraging start and indicate that early thinking is being put into how to make the transition to net zero emissions. However, the Authority is of the view that these goals need to be backed up by detailed practical plans which show how these organisations propose to reach these goals. Specifically, investors should be informed of the investment decisions companies are making in new low- and zero-emitting production processes, when these new technologies will be implemented in production systems, and the quantity and type of offsets, if any, they are planning on using as part of their plans to address their emissions.

The reporting of climate related risks for entities should be based on the publication and annual update of a climate change plan or roadmap. In this document entities should publish their long term and short-term emissions reductions goals and their plans to achieve these goals.

The Climate Council has recommended the draft Safeguard Mechanism settings released by the Australian Government be updated to clarify that:

- Safeguard Mechanism-regulated facilities must demonstrate practical steps and/or investments in train to genuinely reduce emissions before being able to purchase SMCs or ACCUs to meet their determined baselines;

- Facilities must use some SMCs to account for any remaining emissions before purchasing ACCUs, given their more direct equivalence to the type of emissions produced within the scheme;

- Unlimited use of ACCUs will not be a permanent feature of the scheme. Climate Council recommends that over time, use of ACCUs be progressively phased down to a set percentage of a facility’s total baseline. Differential percentages would be expected to apply based on the sector a facility operates within and therefore the available technology options for achieving genuine emissions reduction;

- Any new coal, oil and gas facilities entering the Safeguard Mechanism after 1 July 2023 will be required to meet their baselines without the use of ACCUs – i.e. using only a combination of best-practice technologies and SMCs.

Andrew Stock, Climate Councillor and energy expert, said the next five years will be a critical window to get ahead of AEMO’s forecast future gas supply shortages, but emphasised opening new gas is not a sensible or workable solution.

Instead, he said it is time to accelerate renewables, storage, energy efficiency and to switch away from gas.

“Opening new gas is not the answer. We have to cut ties with gas by developing greater renewable capacity and more storage in the system, and electrifying our homes and businesses. That will cut greenhouse emissions and save Australians money on their bills, too.”

Mr Stock added the outlook in this year’s report has improved from Winter 2022.

“Essentially, this report indicates our energy situation is in a better place than it was last year. Provided LNG exporters meet their domestic obligations, I doubt there will be gas shortages this winter.

“There is no shortage of hydro power, most gas storages are near full so it would take significant coal plant failures to create a gas shortage. Last year we had a cold, long winter in Victoria and South Australia, and floods disrupted energy supplies in NSW and Queensland. This is not on the cards for the winter ahead.”

Dr Carl Tidemann, Senior Researcher at the Climate Council added: “Australia does not have a gas shortage problem. Australia produces five times more gas each year than we use at home. In fact, 80 percent of Australia’s gas is exported or used by the gas industry itself.

“It’s preposterous to consider expanding gas when the bulk of it is being sent abroad. More gas will not only have disastrous climate consequences, but will continue to expose Australian households to the volatile energy prices we’ve experienced over the last two years.

“As one of the sunniest and windiest countries on earth, the future of our energy is from renewables backed up by various energy storage technologies, including batteries and pumped hydro.”

The Climate Council recommends that from 2025, governments should end all new gas connections to homes and require all-electric replacement appliances. It is also calling for the immediate roll out of interest free loans to electrify households, so that Australian families can save up to $1900 a year on power bills.

The second reading of the Safeguard Mechanisms (Crediting) Amendment Bill 2022 took place on Monday March 20.

The Bill Amends the National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting Act 2007 to create safeguard mechanism credit units (SMCs) and provide for related registration, transfer and compliance arrangements consistent with the treatment of Australian Carbon Credit Units (ACCUs); Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 to provide that SMCs receive the same tax treatment as other specified units; Australian National Registry of Emissions Units Act 2011 to: provide ownership and transfer arrangements for SMCs; require the publication of information about holdings and cancellations of SMCs; and provide for the making of legislative rules to increase transparency of information on unit holdings or allow for the voluntary surrender of units; Clean Energy (Consequential Amendments) Act 2011, Clean Energy Regulator Act 2011 and National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting Act 2007 to: provide that protected information includes all information held by the Clean Energy Regulator regardless of when it was obtained; and make consequential amendments; and Carbon Credits (Carbon Farming Initiative) Act 2011 to: enable legislative rules to prevent the regulator from entering into carbon abatement contracts that reduce covered emissions of facilities covered by the safeguard mechanism; require the regulator to consider the safeguard mechanism when assessing the regulatory additionality of proposed offsets projects; and make a consequential amendment.

House of representatives Crossbench MP's who have drafted amendments include Dr. Sophie Scamps, Kylea Tink, Allegra Spender and Zali Stegall.

As part of that second reading and debate, Ms Steggall, MP for Warringah, stated;

''Since 2019 it has absolutely been my focus to champion stronger action on climate change and put forward sensible solutions that should be able to be bipartisan. I put forward a climate change bill, which in fact would have made this mechanism unnecessary because it would have ensured that we had clear guidance on pathways to decarbonisation from an independent climate change commission. That is a proven method in other countries, like the UK. Unfortunately, that wasn't progressed by the government, so here we are tinkering around the edges of a policy that my predecessor in Warringah implemented when he dismantled the Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme, and we know it is a far-from-perfect method. In fact, it has failed to deliver any significant emissions reduction in the heavy-industry sector. But, that said, if done right, the safeguard mechanism has the potential to significantly contribute to the achievement of emissions reduction targets. It does cover, in Australia, facilities that emit over 100,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalents. These are the biggest emitters in the country, excluding the power companies. There is some argument that, in fact, this should be extended to more facilities that are high emitters and that they should be captured. We know there are about 215 facilities included at present and they represent about 20 per cent of our national emissions.

It's difficult to comment with finality on the bill because we don't know ultimately where we it will end up, and there are still conversations I'm having with the minister and other members of the crossbench and the Greens in this House and the other place. But it is important to point out that the safeguard mechanism bill is an important pillar of the government's climate policy. We know we had to push the government to acknowledge that the 43 per cent emissions reduction by 2030 is really a floor not a ceiling and that we have to be more ambitious than that, which means the levers we put in place in this bill, the very pillar to deliver the government policy, has to be capable of greater ambition. That's why so many of the amendments are important.

What this bill does, to cut through all the explanations, is it sets up safeguard mechanism credits as a new form of incentives to help large emitters accelerate decarbonisation. If they overachieve their emissions reduction beyond the 4.9 per cent per annum baseline set by the government then they are given a credit that can be traded to other safeguard facilities at market price. This is a good initiative and one that rewards actual abatement. From there, things get a little bit more complicated. The regulations, the rules around this, are still being developed, and, while there has been good progress in discussions with government, it is still not sufficient. I welcome the consultation process that has occurred so far, but we need to point out that there is room for more ambitious targets if we are genuine in committing to the Paris Agreement and the target temperature of close to 1.5 degrees. In all this discussion, apart from the political grandstanding that goes on in this place, we have to remember what the ultimate goal is, which is keeping warming to a livable status to make sure that we have stable environments in our communities so that our way of life can continue. That has to ultimately be the goal.

The 30 per cent reduction in emissions from safeguard facilities by 2030 is good, but it really should have been 30 per cent from 2005 levels, like all other emissions, not from today's level. The devil's always in the detail of just what you're requiring the industry players to do. Adjustments to baselines for emissions for safeguard facilities and that new facilities will have baselines set in accordance with global best practice are good things. The initiative to set five-year budgets for safeguard facilities post-2030, in fact, is in line with the carbon budgeting approach proposed in my own climate change bill. However, the mechanism does have some gaps. It must address gross emissions. We must prioritise real abatement over purchase of offsets, especially for coal and gas facilities. The mechanism should set a higher decline rate for coal and gas facilities. I totally accept that for about 50 per cent of facilities—heavy industries, steel, ammonia, cement, concrete—it will be incredibly difficult. But for coal and gas it is not difficult, and they should be able to have higher decline rates, which should be in this bill. We should not be allowing unfettered use of carbon offsets to achieve reductions—again, in particular for coal and gas facilities. A new fossil fuel entrant should enter the scheme net neutral. They should be displacing high-emitting alternatives.

The number of 1,233 million tonnes of net emissions is far too great. It has allowed room for growth in emissions and new entrants. The minister himself has said there is a buffer zone built into this to allow for new projects. It allows for at least three large new gas projects to come online—Pluto, Browse and Barossa, Western Australian projects—despite the fact the International Energy Agency tells us 'no new coal and gas' to have a chance of staying close to 1.5 degrees. Modelling from RepuTex shows that the potential for new entrants, especially fossil fuel producers, risks blowing out that budget and, with it, our 2030 target. The modelling shows that financially committed new projects will be substantial, totalling some 56.6 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent, leading to the budget being exceeded by 30 million to 35 million tonnes. The minister and the government dispute that, but we should be requiring new fossil fuel entrants to come online net neutral. We need to ensure that they are not adding to emissions and that they don't force other facilities covered by the mechanism to work harder to keep within the overall budget. It pits new entrants against potential growth industries in critical minerals and manufacturing. We've got cement and steel smelters and fertilisers. These are industries that will remain in the future. We need to invest in new energy sources to support their transition, not make their life harder by continuing to approve fossil fuel projects that will increase our emissions but have limited life span.

The new mechanism allows for unfettered use of offsets to achieve reductions. This is concerning and creates a disincentive to invest in onsite abatement and real decarbonisation. It might, in fact, encourage some facilities to wait when we know there is urgency. In other countries such as the US, they are moving on and investing in important new industries such as green hydrogen. The unlimited use of offsets in Australia provides companies the opportunities to wait on decarbonisation and invest in offsets rather than in the inevitable technology and actually abate emissions. We should be working with industry to bring down the cost of green hydrogen as an input and creating incentives for business to decarbonise now, accelerating the transition, and not have any incentive for facilities to wait.

Capping the offsets at $75 per tonne allows industry to pay their way out of cutting emissions more cheaply than the market may otherwise determine. That's concerning. There could be a shortage of credible offsets in the market. Just a few days ago, in fact, the New South Wales Treasury recommended including carbon emission pricing in line with the EU emissions trading scheme that is currently at $123 per tonne and rising in real terms. The escalating cost of offsets is more reflective of current market demand for offsets, and I think it will incentivise the creation of offsets as well as industry to actually invest. We must implement the recommendations of the Chubb review, as a matter of urgency, to boost the integrity of the scheme to ensure that facilities are investing in quality offsets. If not, all this is an accounting trick. It won't add up to anything, and we will have an escalating disaster when it comes to our emissions.

The bill itself establishes a new form of offset, the safeguard mechanism credit, which is a good thing. This is granted when a facility achieves reductions in emissions greater than the 4.9 per cent decline rate. It is a good thing. We want to incentivise accelerated emissions reduction. The legislation needs to establish a hierarchy of emissions reduction for: firstly, onsite real abatement; secondly, offset projects; and, lastly, as a last resort, purchase of offsets. SMCs—safeguard mechanism credits—represent real growth reductions in emissions. That is what we should be aiming for and prioritising.

Lastly, it's very important that we address methane. The key gap in this proposed legislation so far is greater transparency and accountability for methane emissions by the designated facilities. Last year, Australia signed up to the Global Methane Pledge: to cut 30 per cent of methane emissions by 2030. Most people think methane just comes from agriculture, and we have this ridiculous discussion about barbecues and farting cows. What we really need to talk about is the fact that fossil fuel mining creates 40 per cent of our methane emissions, and we absolutely can do something about this. This legislation is the mechanism by which we can absolutely do that.''

There are currently more than 100 new coal and gas projects in the development pipeline in Australia. Those likely to proceed this decade could generate enough emissions in 2030 for the coal and gas sector to exceed the Safeguard Mechanism’s entire emissions budget.

''When it comes to climate change, coal and gas cannot be treated like everything else. These fossil fuels are the primary drivers of climate change, and no amount of offsetting can replace limiting new developments.'' states the Climate Council

The Business Council of Australia, which has among its membership Woodside, whose profits have trebled, Origin, Brookfield, AGL, the Bank of China, and gas giants Jemena which own and operate over $11 billion worth of electricity and gas assets across eastern and northern Australia, made a submission to to Senate Standing Committee on Environment and Communications Inquiry into the Safeguard Mechanism (Crediting) Amendment Bill 2022, via BCA President Tim Reed and Chief Executive Jennifer Westacott AO, and were urging the Bill to be passed without any amendments;

''The Business Council has a longstanding position supporting sensible climate policy that cuts emissions while guaranteeing affordable, secure and reliable energy. We believe market-based mechanisms are the best way to drive investment into low emissions technology.''

''We are now at a pivotal moment where we have the opportunity to build on the momentum that Australian businesses have achieved over the last five years and head towards a more ambitious 2030 agenda.

But without policy certainty and policy realism, we run the risk of another five to 10 years of delay and inaction. Meanwhile our competitor countries will overtake us in the development of new products and the development of new technologies such as hydrogen.''

''The BCA’s landmark Achieving a net zero economy report outlined a 7-point climate policy architecture to reach net zero by 2050. At the centre of this plan was an enhanced safeguard mechanism supported by a credible offset market.

This plan was the culmination of two years of detailed work with extensive and widespread input and engagement from BCA members. Our membership covers the entire spectrum of the economy, including energy users, producers, retailers, generators and financiers. They all said our policy architecture and supporting principles were the best means of achieving a more ambitious, mid-term target and net zero by 2050.

''Our message – business needs certainty to invest; Our message to this committee is simple – business needs certainty to invest and without attracting significant investment, Australia will be severely limited in its ability to meet its binding commitment to reduce emissions by 43 per cent by 2030 towards net zero by 2050.

The reformed Safeguard Mechanism provides that certainty while pushing the country closer than it has been for a decade to achieving a credible and practical pathway to net zero.''

And ''We support the reform Safeguard Mechanism’s objectives to achieve a net zero emissions economy which delivers new industries, new exports, new jobs, new opportunities and better living standards. If the economy is knocked off course, we risk our global competitiveness as our other major trading partners continue to decarbonise.

Business does not underestimate the difficulty of the emissions reduction task, but policy certainty is crucial. No one can afford a repeat of the mistakes of the past. The perfect cannot be the enemy of the good; too much is at stake.

Our approach must be gradual, technology neutral, maintain reliability of the energy system and supply feedstock for industry. If we attempt to push the system too hard and too fast, we risk falling short.''

The BCA has put forward it's own recommended design for a reformed Safeguard Mechanism, which was first contained in our Achieving a net zero economy report.

It recommends:

- Emissions need to reduce predictably and gradually over time to contribute to Australia’s emissions budgets and in a way that supports international competitiveness.

- Explicit support is required for Australian businesses in internationally exposed, hard to abate sectors where and while technology gaps remain.

- Measures to support these businesses should not come at the expense of other sectors in the economy and should be guided by proper assessment of the threat of carbon leakage.

- The creation and trading of safeguard credits within the scheme is essential to minimising the cost of the scheme to businesses and consumers. The first priority is to deepen and improve the Australian domestic market.

- The future use of international credits needs to be considered. Australian Carbon Credit Units (ACCUs) and international offsets are a critical part of global efforts to reduce emissions by allowing Australian companies to participate in credible and accredited carbon offset schemes.

The BCA states 'ACCUs are not a ‘free ride’

''Most companies are investing in decarbonisation because they know their access to capital, carbon-intensive exports and products are at risk. They are not doing it to tick a box. Companies know they need to decarbonise as soon as possible but technology gaps currently exist. This is why there is a role for credible offsets.

ACCUs for safeguard facilities are not a ‘free ride’. The cost of these offsets is not low. Take a large steel works facility with total emissions of 6 megatons per year.

That facility only has access to technology that can reduce emissions 1 per cent until 2030 when new technology comes online. This is because new technology takes time and capital to develop and deploy at scale.

Under the safeguard mechanism that facility’s emissions baseline will decline by 4.9 per cent per year, to stay under it they will need to purchase offsets (ACCUs or SMCs) to be in compliance with the scheme.

If we assume an average cost of $50 per offset until 2030, which less that the current $75 cap on ACCUs, the cost to that facility of meeting it’s safeguard obligations will be $375 million, plus the cost of the 1 per cent emissions reductions per year.

This compliance is being borne at the same time that the facility owner is also investing substantial capital in the development and deployment of its decarbonisation technology at scale.''

Of course, this does not take into account the billions of profits that keep getting announced each quarter by the BCA's members or the hundreds of projects 'in the works' already that analysts state will mean Australia could never reach any 'climate targets'.

Australia has 116 new coal, oil and gas projects in the pipeline. If they all proceed as planned, an extra 1.4 billion tonnes of greenhouse gases would be released into the atmosphere annually by 2030. - in full below

In late February 2023 Greens Leader Adam Bandt stated a new report showing coal and gas emissions will overwhelm the government’s Safeguard Mechanism underlines the need for the government to stop opening new coal and gas mines.

The report released by Climate Analytics found the government has substantially underestimated projected emissions from Australia’s existing and committed coal and LNG production, and that in 2030 these projects alone would exceed the total permitted emission limits of the government’s proposed Safeguard Mechanism. The report shows emissions from gas could in fact increase by 36% and from coal by up to 116% by 2030.

“This report shows new coal and gas will break the Safeguard Mechanism. The numbers are here in black and white. Labor needs to get real. You can’t tackle the climate crisis while opening up new coal and gas mines.” Greens Leader Adam Bandt MP stated

The Climate Analytics Report is available HERE

On Tuesday March 21, 2023, and on the back of the latest IPCC report, the NSW Greens reiterated their policy platform of no new coal and gas by 2030, a meaningful just transitions’ package for affected workers, as well as a plan to get one million homes off gas and ensure energy efficient rental homes for the two million rental properties in NSW.

New South Wales is a leading contributor to the climate crisis. As the 4th largest exporter of coal globally, NSW has a key role to play in tackling the climate crisis by phasing out fossil fuels and reducing global emissions.

“The latest IPCC report couldn’t be clearer. We must end coal and gas by 2030 if we are to have any hope of tackling runaway, dangerous climate change,” Greens MP Cate Faehrmann said.

“Mining and burning coal and gas is the leading cause of the climate crisis. Coal and gas are causing more extreme floods, fires, heatwaves and droughts in NSW.

“The growing climate crisis threatens our safety and health, our food and water and even the air we breathe. We’ll also feel increasing economic stress, such as paying more for food, petrol, insurance, health services and energy bills.

“Since the Paris Climate Agreement, this Government has approved 26 new coal and gas projects which will be responsible for 4.4 billion tonnes of CO2, while another 8 coal projects are in the NSW planning system.

“Just these 8 projects alone, if approved, will produce a further 1.5 billion tonnes in carbon emissions globally.

“Neither Labor nor the Liberal-National parties will stand in the way of these climate-wrecking projects or recognise the immediate and urgent need for climate action now - the science could not be clearer.''

The Climate Council has made recommendations, as summarised below; further discussion and supporting data on each is outlined through their submission.

Recommendation 1

Climate Council recommends the final Safeguard Mechanism settings require covered facilities to collectively achieve a 43 percent reduction in emissions by 2030 – in line with Australia’s national emissions reduction target. This will ensure that our biggest industrial emitters genuinely pull their weight in the shared national effort to rapidly cut emissions this decade. The proposed carbon budget of 1,233 million tonnes CO2e emissions between 2021 and 2030 should be set as an absolute cap on scheme emissions, fixed in legislation or regulation.

Recommendation 2

Climate Council recommends the final Safeguard Mechanism settings explicitly establish a carbon mitigation hierarchy, whereby facilities must demonstrate genuine efforts to avoid and reduce emissions before relying on credits or offsets. Within this hierarchy, we further recommend that Safeguard Mechanism facilities be required to use any available Safeguard Mechanism Credits (created within the scheme) to account for their emissions above baseline, before using Australian Carbon Credit Units (created through other methods) outside the scheme.

Corporations relying on offsets and credits to meet their Safeguard Mechanism baselines should be required to transparently report on the type and volume of each used, for each compliance year. This will provide valuable data for ongoing assessment of the role of offsets and credits in the scheme, and ensure that companies are accountable to their shareholders and the Australian community for the genuineness of their emissions reduction efforts.

Recommendation 3

Climate Council recommends use of offsets be progressively phased down following an initial period to enable business planning and investment. The Australian Government should outline a clear pathway for progressively declining offset use as part of the final scheme settings commencing on 1 July.

Recommendation 4

Climate Council recommends public funding provided to Safeguard Mechanism facilities through the Powering the Regions Fund should only be used to support genuine business transformation to decarbonise operations. The funding rules should explicitly state that the purchase of ACCUs is not eligible expenditure. Companies receiving public funds should be required to make a legally-binding commitment that these will not be used for this purpose as part of the grant terms.

Recommendation 5

Climate Council recommends the Australian Government remove ‘adapted for the Australian context’ from the final scheme settings for new entrants, and provide clear, specific guidance on what constitutes international best practice for each of the sectors represented within the Safeguard Mechanism as part of the final scheme settings.

Recommendation 6

Climate Council recommends any new or expanded project which would meet the threshold for entry to the Safeguard Mechanism be required to be assessed under a strengthened Environment Protection, Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. A pause should be placed on any new or significantly expanded projects of this scale entering the Safeguard Mechanism until the government’s in-train reforms to the EPBC Act are in place.

Recommendation 7

Climate Council does not support new fossil fuel facilities entering the Safeguard Mechanism. International expert advice and the science is clear that new fossil fuel projects are inconsistent with holding global warming as close as possible to 1.5 degrees.

However, if any new or significantly expanded fossil fuel facilities do proceed, Climate Council recommends these be made ineligible for any forms of government support available to existing Safeguard Mechanism facilities. This includes making such facilities ineligible for funding under the Safeguard Transformation Scheme within the Powering the Regions Fund, and ensuring they are not able to access the proposed trade exposed baseline adjustment mechanism.

These steps will ensure that all public support available through the Safeguard Mechanism is directed to key national industries with a long-term future in a decarbonising world.

Recommendation 8

Climate Council recommends that access to the proposed trade exposed baseline adjustment arrangements should be tightly restricted. Access to these arrangements should not be expanded to a wider segment of facilities or industries within the Safeguard Mechanism as part of the final scheme settings. In particular, existing fossil fuel facilities within the mechanism should never be eligible for reduced baseline decline rates under these arrangements.

Climate Council recommends exploration of carbon border adjustment measures for Australia be pursued as a priority in parallel with reform of the Safeguard Mechanism.

Recommendation 9

Climate Council recommends the Australian Government deliver a major package of initiatives and investment explicitly aimed at developing Australian green export industries to replace exported fossil fuels over time, in parallel with reform of the Safeguard Mechanism. The size and scope of this package should reflect the once-in-a-century opportunity currently in front of Australia to become the world’s supplier of choice for clean energy and green manufactured goods.

Australia’s 116 new coal, oil and gas projects equate to 215 new coal power stations

Richard Denniss, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National UniversityAustralia has 116 new coal, oil and gas projects in the pipeline. If they all proceed as planned, an extra 1.4 billion tonnes of greenhouse gases would be released into the atmosphere annually by 2030.

To put that in perspective, Australia’s total domestic greenhouse gas emissions in 2021–22 were 490 million tonnes. So annual emissions from these new projects would be the almost three times larger than the nation’s 2021-22 emissions. That’s the equivalent of starting up 215 new coal power stations, based on the average emissions of Australia’s current existing coal power stations.

The reason we can get away with this is the current global framework for emissions accounting only considers emissions generated onshore. And almost all coal, oil and gas from these new projects would be exported. But as we share the atmosphere with the rest of the people on the planet, the consequences will come back to bite us.

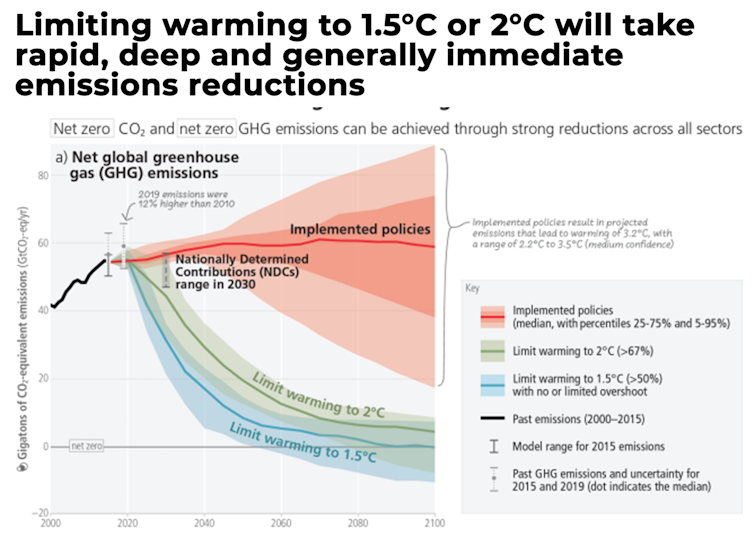

This week the Synthesis Report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) described how fossil fuels are wreaking havoc on the planet. The science is clear: the IPCC says fossil fuel use is overwhelmingly driving global warming.

“The sooner emissions are reduced this decade, the greater our chance of limiting warming to 1.5℃ or 2℃. Projected CO₂ emissions from existing fossil fuel infrastructure (power plants, mines, pipelines) without additional abatement exceed the remaining carbon budget for 1.5℃,” the IPCC says, let alone new coal, oil and gas projects.

In the words of UN Secretary General António Guterres:

Every country must be part of the solution. Demanding others move first only ensures humanity comes last.

Guterres added that “the Acceleration Agenda calls for a number of other actions”, specifically:

No new coal and the phasing out of coal by 2030 in OECD countries and 2040 in all other countries

Ending all international public and private funding of coal

Ensuring net zero electricity generation by 2035 for all developed countries and 2040 for the rest of the world

Ceasing all licensing or funding of new oil and gas – consistent with the findings of the International Energy Agency

Stopping any expansion of existing oil and gas reserves

Shifting subsidies from fossil fuels to a just energy transition

Establishing a global phase down of existing oil and gas production compatible with the 2050 global net zero target.

Hidden in plain sight

Our new research, released today by the Australia Institute, reveals the pollution from Australia’s 116 new fossil fuel projects. These are listed among the federal government’s major projects.

Government analysts estimate each project’s start date and annual production figures. If they are correct, by 2030 the projects would produce a total of 1,466 million tonnes of coal and 15,400 petajoules of gas and oil.

Then it’s fairly straightforward to calculate emissions. We simply multiplied these enormous new fossil fuel volumes by their “emissions factors”. When one tonne of coal is burned it releases approximately 2.65 tonnes of carbon dioxide or its equivalent (CO₂-e) into the atmosphere, and burning one terajoule (0.001 petejoules) of natural gas results in 51.5 tonnes CO₂-e.

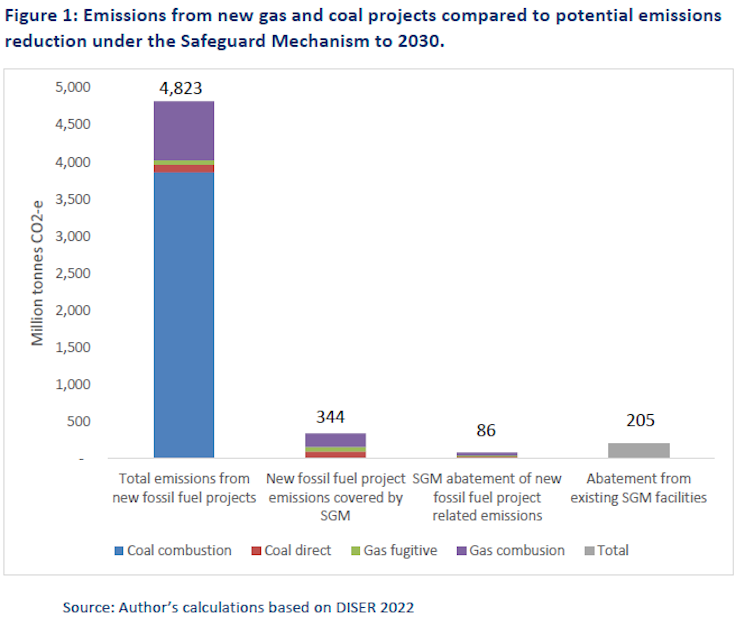

Combined with the 164 million tonnes of emissions that the mining of these fuels would cause, the result is a planet-warming, but spine-chilling, total of 4.8 billion tonnes by 2030.

This amount is 24 times greater than the ambition of the federal government’s key emissions reduction policy, the so-called Safeguard Mechanism. That aims to reduce emissions by 205 million tonnes over the same period.

Rather than embrace the task of decarbonising the Australian economy, the Albanese government has continued down the path laid out by the former Coalition government. It’s a path that relies more heavily on the use of carbon offsets than curtailing coal and gas.

Even though the rest of the world is committed to burning less fossil fuels, there are more gas and coal mine project proposals in Australia today than there were in 2021.

Note also that this list does not include several large, advanced projects actively supported by Australian governments, including Santos’s Barossa gas field, Shell’s Bowen Gas Project, Chevron’s Cleo Acme, and several vast new unconventional gas basins including the Beetaloo, Canning and Lake Eyre basins.

3 reasons to change our ways

Climate Change Minister Chris Bowen argues that Australians are not responsible for the emissions from our fossil fuel exports. That’s because the international accounting rules distinguish between the emissions that occur within our borders (known as scope 1 and 2 emissions) and those that occur when other countries burn the coal and gas we sell them (known as scope 3 emissions).

But if Bowen really wants to tackle climate change, there are three reasons both he and Australians should bear this responsibility:

First, there’s the moral argument. Australia didn’t ban whaling and asbestos mining because we wanted to stop Australians from eating whales or building hazardous homes. We stopped these activities because they were dangerous. Countries can and do shape the world they live in.

Second, even just the emissions in Australia from these 116 new fossil fuel projects (their methane leaks, fuel use and other relevant emissions in Australia) will pour 344 million tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere by 2030. That dwarfs the 205 million tonnes of emissions the entire Safeguard Mechanism is supposed to save over that same period.

And finally, leaving aside the risks of catastrophic climate change, which is admittedly a big ask, it is hard to overstate the risks to the Australian economy of continuing to focus our investment on the expansion of export industries that the rest of the world is committed to transitioning away from. If we aimed the $11 billion per year we spend on fossil fuel subsidies at decarbonising our economy, we would slash emissions in no time.

No new coal, oil and gas

The Australian government continues to support unlimited growth in fossil fuel production and export, despite clear statements from the United Nations, International Energy Agency (IEA) and IPCC that new fossil fuel projects are incompatible with global temperature goals.

No matter where in the world Australian fossil fuels are burned, they will turn up the heat. We can’t escape the simple truth that humanity must stop burning fossil fuels. It’s the only path to a liveable future.![]()

Richard Denniss, Adjunct Professor, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.