July 11 - 17, 2021: Issue 501

NAIDOC Week 2021: Heal Country - ‘Although We Didn’t Produce These Problems, We Suffer Them’: 3 Ways You Can Help In NAIDOC’s Call To Heal Country + Will Your Grandchildren Have The Chance To Visit Australia’s Sacred Trees? Only If Our Sick Indifference To Aboriginal Heritage Is Cured + Australia Post Celebrates NAIDOC Week With Traditional Place Names On New Satchels

‘Although we didn’t produce these problems, we suffer them’: 3 ways you can help in NAIDOC’s call to Heal Country

NAIDOC week has just begun and, after several tumultuous years of disasters in Australia, the theme this year is Heal Country.

In the last two years, Australia has suffered crippling drought that saw the Darling-Baaka run dry, catastrophic bushfires, and major flooding throughout coastal and inland areas of Australia’s east.

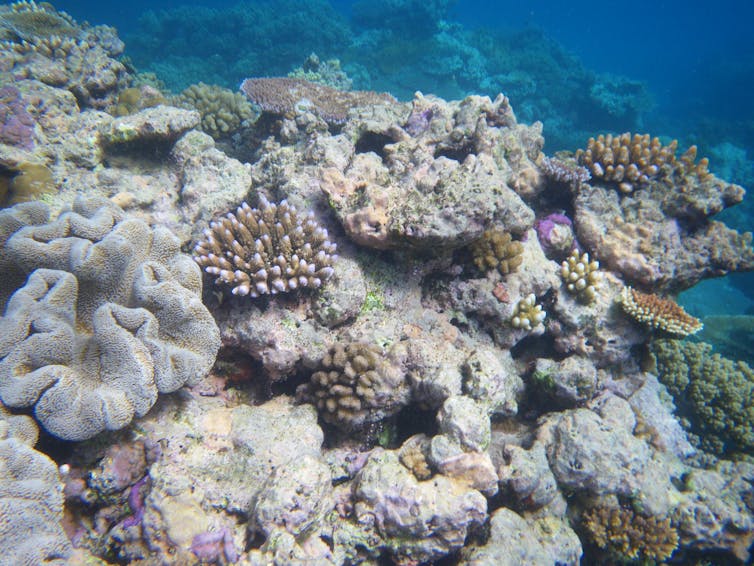

Just two weeks ago, UNESCO’s World Heritage Centre recommended one of our national treasures, the Great Barrier Reef, be listed as in danger.

If these events, and the thought of other inevitable climate change-driven disasters sadden or madden you, consider how it impacts Indigenous peoples.

So with this in mind, and the rest of NAIDOC week ahead of us, let’s take a moment (most likely from lockdown) to explore the theme of Heal Country in more detail.

More Than A Landscape

For Indigenous people, Country is more than a landscape. We tell, and retell, stories of how our Country was made, and we continue to rely upon its resources — food, water, plants and animals — to sustain our ways of life. Country also holds much of our heritage, including scarred trees, stone arrangements, petroglyphs, rock art, tools and much more.

Indigenous people talk of, and to, Country, as they would another person. As the late eminent ethnographer Deborah Bird Rose famously wrote:

Country is not a generalised or undifferentiated type of place, such as one might indicate with terms like ‘spending a day in the country’ or ‘going up the country’.

Rather, Country is a living entity with a yesterday, today and tomorrow, with a consciousness, and a will toward life.

As cultural and spiritual beings, and with deep and ongoing attachments to lands and waters, the impacts of climate change interrupt and make uncertain our unique ways of life. This increasing reality is shared with Indigenous peoples all over the world.

These sentiments were captured by Tishiko King, a Kulkalaig woman from the island of Masi in the Torres Strait. In her reflections on returning home in December 2020, she explained:

I had to pick up the bones of my Elders because erosion is damaging our burial sites. As First Nations people we know that these are our spirits of our old people, and it’s a sign of disrespect.

It’s desecrating who they are. It’s that heart-wrenching pain in your chest.

This is why the National NAIDOC Committee has sought to draw attention to our struggle.

Why Heal Country?

Through this year’s theme, the National NAIDOC Committee invites the whole nation to embrace “First Nations’ cultural knowledge and understanding of Country as part of Australia’s national heritage”.

This requires understanding the depths of Indigenous peoples’ connections to Country and treasuring our heritage values.

But “understanding” and “treasuring” will only go so far in the face of increased drought, more severe storms or changing seasons and animal behaviours as a result of climate change.

As Bianca McNeair, a Malgana woman from Western Australia and co-chair of the First People’s Gathering on Climate Change, shared with The Guardian:

[Traditional Owners] are talking about how the birds’ movements across country have changed, so that’s changing songlines that they’ve been singing for thousands and thousands of years, and how that’s impacting them as a community and culture.

All Australians have much at stake if radical steps to cut emissions aren’t taken. For Indigenous peoples, the consequences of climate change are much more profound.

Not All Disasters Are Natural

But talking only of climate change doesn’t capture the full reality threatening Indigenous peoples ways of life.

The destruction of Juukan Gorge by Rio Tinto in 2020 caused international outrage for the clear disregard for not only Indigenous culture, but human history.

Likewise, the notorious McArthur River mine in the Northern Territory has been damaging the environment and nearby township of Borroloola, from the leaking of potentially harmful contaminants to waste rock that smouldered for months.

These events, as well as others, continue to be examined through the Juukan Gorge Senate inquiry.

Heal Country forces us to see these events not in isolation, but in a chain of disasters that continue to impact and threaten Indigenous peoples. It invites people to see the land and water through our eyes and understand that although we didn’t produce these problems, we suffer from them.

Heal Country seeks reflection, for all Australians to ask themselves what they treasure about being from, and living on, this land.

If, like us, you find peace, pride and enjoyment from our natural values — our beaches, mountains, rivers, wetlands, forests, deserts and more — then perhaps it’s time to get off the bench and become an advocate for change.

Read more: Rio Tinto just blasted away an ancient Aboriginal site. Here’s why that was allowed

Three Ways You Can Help

Indigenous people continue to stand up for and protect their Country. But in a nation where their connections, culture and heritage are seen by governments as being of lesser value than minerals, it is often a lonely struggle.

I asked people to consider the impacts on Country, culture and heritage in my article for The Conversation during the 2019-2020 bushfires. Now, I ask that you consider it against the backdrop of an uncertain future.

Far from being powerless to protect Country, there is much an everyday Australian can do. Here are three examples:

1) Make a submission to the Juukan Gorge inquiry.

The Juukan Gorge inquiry is one of the most important in our recent history. The protection and management of Indigenous peoples’ culture and heritage is being thoroughly examined, with recommendations to better balance the protection of these things against future economic growth.

You can lend your voice — or that of your organisation — to express support and solidarity with Indigenous peoples through a submission.

2) Donate to charities that support Indigenous land and sea management programs.

These organisations are key to advocating on behalf of Indigenous people and offer guidance, advice and support to Indigenous communities seeking to establish their own programs. Two of note include Firesticks Alliance and Country Needs People.

3) Write an email to your local member.

Ask your local member how they’re supporting local Indigenous land and sea management programs, including ranger groups or cultural burning initiatives. If you live in the city, ask how their party supports Indigenous groups in their caring for Country aspirations.

Read more: Strength from perpetual grief: how Aboriginal people experience the bushfire crisis

Heal Country invites all Australians to walk with us, to stand beside us, to support us.

But perhaps most importantly, it invites Australians to love, treasure and fight for this land, as we have done, and will do, forever.

This story is part of a series The Conversation is running on the nexus between disaster, disadvantage and resilience. It is supported by a philanthropic grant from the Paul Ramsay foundation. You can read the rest of the stories here.![]()

Bhiamie Williamson, Research Associate & PhD Candidate, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Will your grandchildren have the chance to visit Australia’s sacred trees? Only if our sick indifference to Aboriginal heritage is cured

Trees have always been a point of conflict between colonisers and Indigenous people.

At the very beginning of European-Indigenous interactions, skirmishes broke out because colonisers were ignorant of protocols and the desecration of important Indigenous sites and habitats. In the 19th century, as frontiers pushed west into the Country of Wiradjuri, colonists were indifferent to the sanctity of marked trees.

As a news article from the Daily Advertiser in 1941 reported:

The only carved tree […] unfortunately fell victim to the advancing tide of civilisation and was cut up and converted into railway sleepers that now possibly lie somewhere along the line between Yanco and Hay, or Leeton and Griffith.

Most recently, the binary difference between Indigenous and non-Indigenous systems were in the spotlight as Djab Wurrung custodians and activists fought to prevent the desecration of Djab Wurrung sacred trees. Dozens camped to protect a 350-year-old Djab Wurrung Direction Tree, and a Grandmother Tree estimated to be 800 years old.

This conflict showed it is not necessary for a tree to be modified for it to be considered sacred. It also showed us this failure, centuries old, is one born from a conflict of ideas and beliefs between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people.

This year’s NAIDOC theme “Heal Country” asks all Australians to take stock of the ongoing threat and desecration of Indigenous heritage — including sacred, cultural trees. This heritage not only holds value for Indigenous Australians, but for all Australians as a cornerstone of our national identity.

Sentinels In Ceremony, Birthing And Burials

Aboriginal ontology captures the relationship between all worldly and spiritual phenomena, and relationship to Country.

Aboriginal people view the landscape and all things within it not as inanimate places or objects, but as sentient landscapes and entities with agency and metaphysical properties.

Sacred trees are pivotal points in a nexus of interpersonal relationships between person-animal-plant, in person-person kinship, in identity and connection to place. They hold our ancestor stories, they are a direct link to our old people.

Trees transcend simple economics and sit at the centre of the sacred — they are sentinels in ceremony, birthing and burials.

In Wiradjuri Country, carved trees marked ceremonial grounds and burials. Burial trees were decorated with distinct diamond and scroll motifs, unique and powerful, and faced those buried.

Economically, trees provided generations of Indigenous people with shelter, fibre, tools, food and material for canoe-making.

The common thread in Indigenous tree use is its sustainable practice. Rarely would a tree be felled purely for economic gain because its inherent value is realised for spiritual and broader ecosystem health.

Importantly, people-tree beliefs systems are very much alive in Aboriginal societies of southeast Australia.

Read more: An open letter from 1,200 Australian academics on the Djab Wurrung trees

Scarred trees are still commonly made by Wiradjuri people. Species of eucalypt, particularly red gum, yellow and grey box are carved and, when their bark is soft, removed to make coolamons (wood or bark carrying container) and canoes. Red gums are manipulated while young, their branches interwoven. Commonly called ring trees, they are said to mark boundaries and line the banks of the Marrambidya (Murrumbidgee River).

Wiradjuri women still perform the ancient birthing ceremony of returning a child’s gural (placenta) to Country. My daughter’s gural was returned to Country and buried at the base of river red gum sapling on the banks of the Marrambidya.

This is her place now, she is connected to this sapling. It will grow as she grows, and she will return to this spot for the rest of her life.

The Threat Of Public Indifference

Sacred trees also stand at the intersection of Aboriginal heritage and environmental protection, activism and politics. Economic- and wildfire-driven deforestation represent omnipresent threats to sacred trees and Indigenous heritage more broadly.

But even more insidious is the threat of public indifference. It’s a sickness that has spread through our nation’s institutions and political systems.

This sickness shows a lack of respect for Indigenous culture and our humanity. Its symptoms take the form of ongoing desecration of our heritage and incessant dispossession of Indigenous people.

Unless there’s mainstream appreciation of Aboriginal culture and heritage, episodes like the destruction of Juukan Gorge, Djab Wurung and Kuyang will continue, and the public conversation will remain divisive.

The Riverina’s Last Sacred Trees

In a small township called Narrandera situated along the Marrambidya (Murrumbidgee River), sacred Wiradjuri trees still survive. They represent a living continuum between the old ways and the new.

Most of this country along the Murrumbidgee has been consumed by Australia’s unquenchable appetite for land and water. Almost everywhere you look, there are expanses of land cleared to make way for intensive crop cycles. Miles of irrigation fed by the Marrambidya deliver water to thirsty crops and livestock.

The land clearing and deforestation in this part of Australia is staggering, and it doesn’t surprise me that our abysmal record qualified us as the only developed nation on the World Wildlife Fund’s global list of deforestation hotspots.

One exception where communities of old trees still stand is in the Murrumbidgee Valley Regional Park, which hugs the Marrambidya and provides a corridor sanctuary for flora and fauna.

It’s the most important ecological habitat in this part of Bidgee country, not only because of its remarkable biodiversity value (this is the Riverina’s only koala habitat) or heritage value, but more so because of its scarceness.

Read more: Friday essay: this grandmother tree connects me to Country. I cried when I saw her burned

Here, some of the region’s last sacred trees and important Aboriginal cultural sites survive.

The two photos below show a shield tree and a stone core. These were both found in the same stretch of the Murrumbidgee Valley Regional Park.

Sacred trees used to be common throughout the Riverina, but are now found only in a handful of state forests, national parks, or in vegetation reserves hugging the region’s highways. Extrapolating beyond the fence line into farmland, one could presume they were once common throughout this territory prior to colonisation.

A Future For Sacred Trees

We must ask ourselves some tough questions. What will the next two centuries of unrestrained economic and infrastructure growth mean for Aboriginal heritage? Will your grandchildren have the same opportunity to visit and sit with sacred trees on Country — to listen to them, to speak to them and to appreciate them?

The ongoing desecration of Aboriginal heritage and Country, particularly our waterways, directly traumatises Aboriginal people. When we are denied access to Country and our heritage is destroyed, it leads to poorer health, well-being and social outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

This is not just an Indigenous issue, or only about Indigenous struggle. Indigenous heritage is an asset all Australians can enjoy, celebrate, and advocate for greater protection and sustainable management. Once gone, it can never be replaced.

I acknowledge the Wiradjuri and all Indigenous people, their ancestors, elders, and youth, and advocate for their ongoing connection and right to access and protect Country.

I also acknowledge Lillardia Briggs-Houston, Wiradjuri, Gangulu and Yorta Yorta woman, for her advice and contributions to this piece.

Read more: Strength from perpetual grief: how Aboriginal people experience the bushfire crisis ![]()

Rob N. Williams, Archaeologist & PhD Candidate, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Australia Post Celebrates NAIDOC Week With Traditional Place Names On New Satchels

July 5, 2021

Australia Post is marking 2021 NAIDOC Week and its theme, “Heal Country!” by launching new packaging that includes a dedicated space for the inclusion of Traditional Place names for customers who wish to recognise traditional Country on their mail.

The organisation is also reflecting its ongoing commitment to celebrating First Nations culture by wrapping a number of its Street Posting Boxes in Indigenous artwork with a design created by Darwin’s Marcus Lee of the Karajarri People.

Australia Post’s National Indigenous Manager and Noongar man Chris Heelan said the move to provide room for Traditional Place names on satchels comes after being approached by First Nations Gomeroi woman Rachael McPhail, and has come about as a direct result of customer feedback.

Australia Post’s National Indigenous Manager and Noongar man Chris Heelan

“We not only listened to Rachael, but to the overwhelming feedback from thousands of Australians who supported this fantastic concept to recognise traditional Country on their mail”, Mr Heelan said.

“Including the Traditional Place name as part of the mailing address is a simple but meaningful way to promote and celebrate our Indigenous communities, which is something Australia Post has a long and proud history of doing.”

Ms McPhail said she was delighted to see Australia Post build upon her idea and encouraged Australians to expand their knowledge of Indigenous heritage and start including Traditional Place names when sending letters and parcels.

“This is about paying respect to First Nations people, and their continuing connection to Country. If everyone adopts this small change, it will make a big difference,” she said.

The newly designed Parcel Post and Express Post satchels, which also include an Acknowledgment of Country, have a nominated line below the recipient’s name to include a Traditional Place name above the street address and postcode. Traditional Place names can also be used on letters, provided they appear above the street address and postcode.

For tips on how to identify First Nations localities and sending guidelines visit auspost.com.au/traditionalplacenames