November 21 - 27, 2021: Issue 519

Luke Whitington

Poet - Farmer - Businessman

Lovett Bay resident and Artist of the Month for November 2021 Luke Whitington is one of Australia's most beloved poets.

Luke is a business man and grazier with a keen interest in Art. After attending the Australian National University and working for two years in the Department of Foreign Affairs, where he began writing poetry, Luke and his best friend set sail on a cargo boat for Europe.

Luke is a business man and grazier with a keen interest in Art. After attending the Australian National University and working for two years in the Department of Foreign Affairs, where he began writing poetry, Luke and his best friend set sail on a cargo boat for Europe.

He has led a remarkable life spending nearly 20 years in Italy, including two years spent at University of Perugia learning Italian. He went into business with an Italian partner and restored over 100 ancient farm houses and monasteries, mainly in Umbria, with some in Tuscany.

While in Italy he started writing more poetry which led him to Dublin where he restored the 14th Century Norman Castle Portlick situated on the shores of Lough Ree Glasson in County Westmeath.

While there, his keen interest in Art led him to start an Arts Precinct, The Pleasants Factory, in Dublin.

After 10 years he returned to Australia in 2003.

Since 2004 he has been working to improve the family cattle property Currajugg in the Southern Tablelands breeding Angus Aberdeen cattle.

In the last two decades he has concentrated his talents in the Arts writing, reading and publishing his poetry in several locations and journals including Manning Clark House Institute ACT, Quadrant Overland, The Canberra Times, Contrappaso Magazine, the Australian love poem anthology and The Canberra poetry anthology, in Florence, Italy, published by the Sigh press, in the Dublin Irish centre for poetry studies and in the Irish independent media.

One of Luke's poems, Bunyah, was included in the tribute to the life of Les Murray.

His most recent work is “Only Fig & Proscuitto - New and Collected Poems“ published by Ginninderra Press with appraisals by Mark O’Connor and Dr Paolo Totaro AM.

A new collection of his poems, What Light Can Do, is scheduled for release in 2022.

This week a few insights into the works and workings of a 21st century Australian Poet.

Where and when were you born?

I was born in Claremont, Perth, Western Australia in 1947. My mother was from two pioneering farming families in Western Australia. My father Richard Whitington, who was called ‘Dick’, was a cricket writer and commentator and player – he actually played under Bradman. He opened up for South Australia as a 20-year-old with Miller, and Bradman was the captain. He too was from pioneering families, in South Australia.

Jenny Drake Brockman went off in a big way during the week. The "do" took place at the Douglas Gawlers, and Jenny became Mrs. Richard Whitington, all clad in full bridal regalia with sister Molly and Ray Paxton filling the parts of bridesmaid and best man. Firefly (1944, June 3). Mirror (Perth, WA : 1921 - 1956), p. 15. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article76012870

WHITINGTON--On January 2, at St. Anne's to Mr. and Mr. R. S. Whitington – a son. Family Notices (1947, January 4). The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 - 1954), p. 1 (SECOND EDITION.). Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article46253211

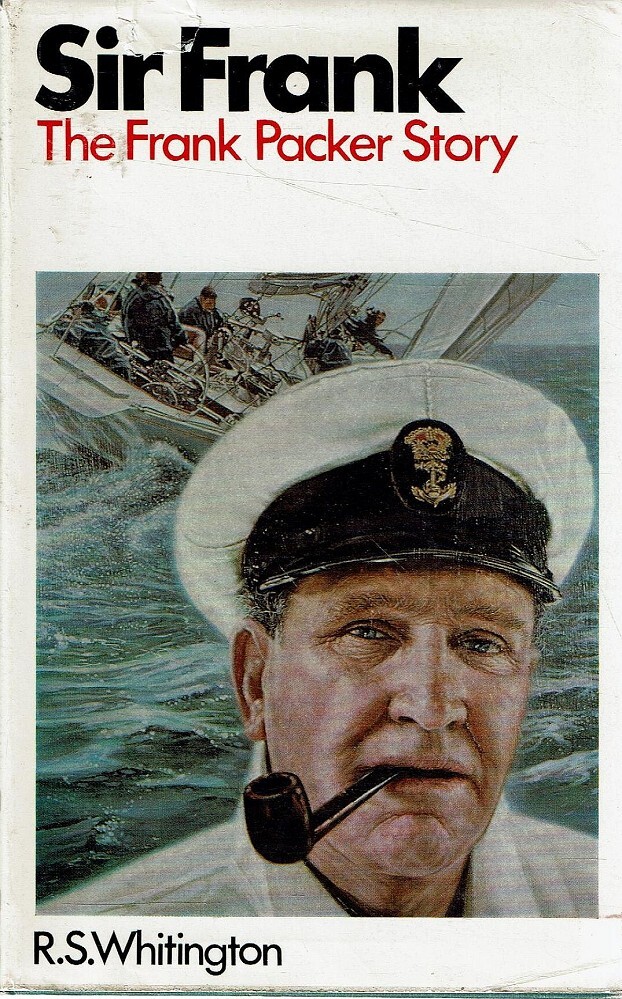

Both of my parents escaped their heritage. He got a job with Consolidated Press in Sydney as their Sports Editor. This was the Frank Packer media outfit then.

Where did you grow up?

My very early years as a baby were spent on Cottesloe Beach. My father was still playing cricket then for South Australia but also writing for the Western Australian newspapers, mainly as an Editor and focussed on sport.

My mother then said she didn’t marry dad to live in Western Australia, so he got a job working for the Packer organisation. He used to go overseas and commentate all the cricket Tests; in South Africa, in England, Ceylon, Sri Lanka – he did that for years. He also wrote the only official biography on Sir Frank Packer, called ‘Sir Frank’.

I grew up in Bellevue Hill Sydney primarily – Antonia (Hoddle) lived across the road and that’s where we met, as kids. She and her sisters and myself used to play hopscotch on the footpath opposite Scots College, on Victoria Road.

When my mother and father divorced I was sent to boarding school in Tudor House in Moss Vale, then on to Kings in Parramatta.

My mother eventually married Major-General Paul Cullen. He was a great Patron of charities such as the Royal Blind Society and Freedom from Hunger among others. They had a very busy life as he was involved in charitable work full time. He was also head of the Australian civilian Military Forces and on all the Boards for these.

He was quite a character; rode horses bareback, loved people, food, conversation and wine, and cooked like a pro.. He was a hero of the war against the Japanese fought on the Kokoda Trail, there have been numerous books written about him. He was awarded the DSO twice.

What did you do after finishing at Kings?

When I returned to Sydney I got in with a very Bohemian crowd in Sydney – a lot of the people you’d run into at one stage or another before they became suitably worthy and respectable. We were living a totally bohemian lifestyle in Edgecliff in a big terrace house.

My parents got terribly worried about me and thought I needed rescuing from Bohemia and so I was sent to Canberra to study – I was only getting 2 units out of 4 at the University of NSW – I was turning up to exams in a penguin suit I’d worn the night before to a party, and falling asleep at the back of the classroom. That’s what a boarding school does for you – you go mad when you get out.

So I agreed to go to Canberra where my parents were keen farmers – my mother has had a number of farms in her life and there is still a farm at Braidwood that belonged to the family – she was from the Drake Brockman family, so she had farming in her blood.

I was living on the farm in Canberra and going to ANU university in Canberra. I was studying American Literature, Political Science and Economics.

I then applied to join Foreign Affairs and had an interview with Sir James Plimsoll in the top of the building; he had an office the size of a department store floor. I walked in and couldn’t believe it – there was this man sitting at a huge desk, which seemed like a hundred metres away.

I went in, sat down, and he said ‘alright Luke, you want to become a diplomat do you?’

I said, ‘that was the general idea sir’. He asked me where I went to school, all these questions, I was still at ANU then, and explained what I was studying. He said it all sounded good and I wouldn’t have to be taught a lot of things and could be an Ambassador before I was 40. All I could say was ‘thank you sir’ – I was speechless. He explained that he was very busy, had a conference with the president of an Asian country to get to, but that everything was good and he looked forward to me joining Foreign Affairs and if I had any questions to ring his secretary up so I could ask him.

So I joined Foreign Affairs but unfortunately became very disillusioned. I was involved with Economic Development of South East Asia. I disagreed with some of their ideas, particularly having to spend so much money every year, where the premise was, whatever you did you had to spend so much money or you wouldn’t get that same amount the following year. This put pressure on us and I didn’t feel we were analysing projects enough. There were also projects that didn’t get analysed at all, cost a lot less, and I felt these were very valid – and they were being rejected. One of these was for Sumatra – I found out that women in Sumatra were delivering a very high rate of blind babies – and this was happening because of a Vitamin C deficiency in their diet. I recommended that we supply them with Vitamin C, and said, very proudly, that this would cost us hardly anything. And that was the end of that project.

So I resigned after that. I was very disillusioned.

I went down to the farm and worked on the farm at Braidwood for a while. After six months I got very sick of that – my mother was very strict and said, ‘'look, a real farmer is a 7 day a week farmer''. I was going into Canberra to see friends of a weekend and she thought that was just a waste of space and time and I should commit myself to 7 days a week.

Then a friend I went to school with owned a farm at Michelago, the Ryrie family, James Ryrie, rang me up and said, ‘do you want to come with me, I’m going to Europe’.

James explained he was going to stay away a couple of years. I said it sounded wonderful. He said we had a passage on a P&O container ship and all we’d have to do is pay for our food and do a few jobs.

We had four or five jobs to do each day; the worst one was chipping the rusted decks. This involved taking a cold chisel and a heavy sledgehammer or mallet and banging the cold chisel down onto the rusted surface of the deck to chip off the rust before it is repainted. Ship’s steel is possibly the hardest steel that’s made – it would take the pair of us working together, wearing huge hats as the sun was very intense, for a whole day and we might get two square feet done.

How long did the passage take?

30 days. This was in 1971, 1972. We got on the ship in Melbourne but it went right around Australia, from Brisbane to Sydney to Melbourne and then Perth.

How did you commence restoring heritage buildings?

It all started in Umbria. But to go back to the beginning, initially we got off in Germany because James had purchased a car duty free in Munich.

Then James and I got off at Bremerharven and caught the train down to Munich. We picked the car up and started driving - we really had no plan to go anywhere in particular, nor was there any timetable about returning home, or anything. So I was on the road with him, driving, principally around the Mediterranean for two years.

We worked as Life Savers in Spain, as somewhat useless bouncers in a disco in Perugia, and in a restaurant on the Ligurian coast, which was owned by a cousin of Lucio who owned Lucio’s Restaurant in Paddington. A lot of work by Australia’s most famous contemporary artists were hung on the walls of that restaurant.

Mario Guelfi owned a restaurant on the Ligurian coast, right on the Mediterranean and we got a job there, starting off doing manual stuff like cleaning and dishwashing. Then we were taught to cook; which is where I learnt to not only cook Italian food but also how to eat it; which is learning how to use a fork properly – which is dead simple but unless someone tells you how to it’s not necessarily something you will discover.

Mario Guelfi had married an Australian girl from Mudgee, Wendy Lonergan. Wendy was from those wheat farming families up at Mudgee, she loved having some Aussies around, and he enjoyed our company. He told us we had to learn Italian and that we wouldn’t learn it there; we’d learn pidgin Italian – ‘go and study Italian’ and ‘when you come back you will have a permanent position here’.

I didn’t ever go back but I did go to Perugia and spent two years there studying Italian at the university there. James got bored with Perugia and left for the ski resorts and got a job working in Tyrol.

While in Perugia I met an Italian girl and that’s what really set my feet on the ground in Italy. Her family adopted me - the Italians do adopt you, it’s really quite extraordinary. So I was included in everything; if I was missing they’d send out people to find me – lunch is the biggest thing in daily Italian life so if you’re not there then, they send out someone to find you.

So I was studying Italian there and also studying the Italian you don’t get in the textbooks, with Rita, the girl I had met.

I then had to invent a way of staying because I was running out of money. Italy was so cheap then, but you still needed some wherewithal. The thought of going back to Sydney and getting just any old job didn’t appeal to me so I had to come up with an idea.

I thought and thought. Rita and I went out walking every weekend around the Umbrian countryside and we had already discovered this monastery San Faustino; we used to camp there and sleep overnight.

I said to Rita; what are they doing with these beautiful ruins. She explained that the farmers regard them as a liability, for they had no use for them. After finding out this, I discovered their other greatest preoccupation was having to pay for their daughters’ wedding.

The Vatican sold San Faustino to me for the price of a small car. It took 4 years to restore with 4 men and myself, and it is now a hotel. My grandmother lent me the money to buy it, telling me she would never forgive me if I squandered it. I paid her back, with interest.

San Faustino

San Faustino

Luke; an Aussie abroad San Faustino report by Sydney Morning Herald

Following on from this I went to a local real estate office in an Umbrian town and introduced myself and said ‘I’ve got a good idea; do you want to talk about it?’ – which was getting options on buying these old ruins and restoring them - they were everywhere throughout the countryside.

There was an old guy in the office, very properly dressed in a tie and jacket, and he thought I was nuts – I looked like a long-haired hippie. Then in through the door walked this guy who looked like a young Omar Sheriff. He was introduced to me as Fabio – we went to an office in the bowels of this building and talked for 4 hours.

My idea was to put a roof on them and put them on the market with a built-in renovation price. In Italy, then, everyone’s nightmare around this was ‘when is it going to end and how much will the cost be?’ – So by introducing what we call here a Fixed Price Contract that eliminated that concern and the reticence it naturally causes. This also eliminated the opposition because nobody was doing that in Italy.

We set up this company and I went to London and met people at these property shows who were more than interested in collaborating with us. We soon had a huge amount of English clients ranging from stockbrokers to academics and artists.

We then started buying old ruins to restore. The cost of an Italian wedding at that time in Umbria, the maximum you’d spend for an absolute feast that would last two days for 100 guests would be one million lire, the equivalent of one thousand Australian dollars.

We’d go to the farmers and say ‘look, we’ll pay for the wedding but we want the building, the ruins’. They thought we were crazy – they were so happy to give us the building.

Although it didn’t look good after the first year, and I remember apologising to Fabio that it didn’t look like it was going to work out, he replied he’d never had so much fun in his life.

I spent 20 years there and we restored over 107 houses.

Which sticks out in your memory or remains a favourite?

The monastery, San Faustino remains a favourite – San Faustino is the patron saint of water. It was originally a hermitage for monks who made herbal elixirs and built in the late 1100’s.it was totally abandoned when I first saw it; holes in the walls and roof. We divided it into five very large apartments, about 300 square metres each.

You then went to Ireland?

I went to Ireland in 1989-1990, partly because the property market in Italy collapsed. I was living in Florence by that stage and had moved my business into Tuscany and was doing business in both Umbria and Tuscany and had offices in both provinces; they were sister provinces so I could drive across the border quite easily. This also fitted in with my plan to only look for ruins that were on either side of an autostrada so I could get everywhere very quickly – this worked well considering we had jobs all over the countryside.

I was then married to a fashion designer from Florence and the fashion world in Italy died too; there was an economic crisis. She was working with Pucci, was Pucci’s right hand girl, but his business collapsed. He had too many employees and couldn’t bear to sack anyone, which became his downfall. The other reason was to get back to speaking English again.

I first came to Ireland in 1989 to stay with a friend in Dublin, Nicolo D'ardia Carraciolo whose mother, a Fitzgerald, came from Waterford Castle. He was a very interesting man - from an ancient Neapolitan family on his father’s side and a much-liked person – a titled prince, literally, and a very good friend of mine. Nicolo's father, Don Frederico lived as a widower in Ballsbridge, and was the Papal representative in Ireland. His family were involved in a lot of things in Ireland, including horse breeding and other activities.

I was drafting poetry when Nicolo called, in a studio I shared with him in Florence. Nicolo travelled a lot between different landscapes, painting in Ireland, England and Italy.

Nicolo called and said ‘I have found something you should see. I was painting the landscape around Lough Ree and I stumbled across this Norman ruin, it's wonderful, you should restore it!’

Niccolo was the first person that I knew to sight the Portlick Castle.

He said ‘I’ve just started doing some drawings of this castle I found, it’s alongside Lough Ree’, which is the lake of the kings. He said I had to come and look at it.

He faxed me a plan of it and I flew over. It was huge – the bank was selling it – the person who owned it was an American who had gone broke, so they were happy to get rid of it. I got it for relatively little money and so commenced a six-year renovation.

I sold it a few months ago to another American who is going to set it up as a tourist destination.

It was a great project. It was built by a Norman Baron called Hugh De Lacey – he was sent out by King John, Richard the Lionheart’s brother, to settle the Lake District. Vikings were coming down via the Shannon River and going through that district terrorising the local folk and charging exorbitant amounts to those who were trading up and down that river.

He sent Hugh De Lacey to build six castles in this part of the world where my castle was. They were all ruined apart from Portlick Castle by that stage as Cromwell had destroyed five of them. The only reason Portlick survived is because Cromwell’s senior captain fell in love with the daughter of the Norman family of De Leons, which is the Dylans today, who owned it then. Cromwell spared them on the basis that they could set up a base there every time they needed it.

Cromwell then declared the east of Ireland ‘The Pale’ and the west of Ireland ‘Beyond the Pale’. All the Catholics were made to go over to the west side of the Shannon River.

When I lived there it was still predominantly Protestant in the east and Catholic in the west.

To cut a long story short I moved to Ireland and while waiting for development approval on Portlick, I set about restoring old properties in Portobello and Ranelagh in Dublin. I could not believe the abundance of beautiful Georgian structures up for sale at throw-away prices.

One of these was an old canvas jeans factory in Pleasant’s lane in Dublin, which I restored, installing light wells and fire-proof stairs.

My accountant said to me ‘you can’t sell it, you will lose most of the money in taxes. You will do better to keep it and do something with it.’

I met a lot of wonderful people in Ireland during the six years of the Portlick restoration. One of these, a couple, set up a gallery in the Pleasants’ lane factory I’d restored.

We met in a pub in the centre of Dublin and they introduced themselves as the owners of a gallery called ‘The Gutter Gallery’. I asked them where their gallery was to which the reply was ‘it’s outside, on the kerb’. They had all these paintings leaning up against the shops and were selling them on the streets. I said I had a building which they might like to take a look at and maybe we could talk about doing something together there.

We went and had a look at the factory and they said it was perfect ‘a dream for us’. I said they could run a gallery here but they had to set it up – I’d be involved but wouldn’t interfere with how they ran it.

We ran that gallery for 7 years as the ‘Pleasants Factory Gallery’, named after Sir Robert Pleasant. He had set up a home there originally for homeless women. We had poets reading there, performance art, and exhibitions of paintings, with a changeover every 2 weeks.

We had a lot of support from the Dublin press and I met a lot of good people in the arts or associated with the arts through doing this – it actually changed my life.

The Guinness family generously decided to sponsor us so the drink and the chat flowed freely. Up to 600 people at a time would attend the openings.

I was subsequently made a godfather to one of the Guinness heirs.

Irish Press clipping from then

Irish Press clipping from then

We exhibited well over 100 artists during that time. Some of these paintings I decided to collect and these works, formerly on loan to the Dublin Business Centre and then the Irish Museum of Modern Art, are now on loan to the Athlone Institute of Technology and the Arts, including works by Sean Fingleton and Patrick Conningham, and in the latter stages, the Westmeath artist Paul Proud.

In the meantime, I had located artisans and trades to work on Portlick Castle and after creating files and files of paperwork for the council, we were allowed to begin to restore.

I have barely touched on the ins and outs of this journey, but I made many friends in Dublin and in Athlone and Glasson, co. Westmeath, and this was a particularly joyous period of my life.

I have seen Ireland change dramatically over that period and after, when I was required to return to Australia to assume family responsibilities; the energy is positive and vital and art flourishes and this maintains an important doorway into the soul and a step away from the infernal noise of daily life. Without art and artifice there is little trace left of Civilization, I might say also without architectural heritage we have no past. These buildings survive and overcome political categorisation.

I will return regularly as I will be retaining a little corner of Westmeath.

I’d like to take this opportunity to thank all those who helped along the way and especially to Professor Harman Murtagh for his generosity, his astute care for the institute and teaching and his beloved undulating, emerald-green Westmeath.

He is, as you may know, an expert on the Norman incursions into the area and this knowledge was also generously made available to me in my research about Portlick. He has published several books on the subject, for those interested in further research of their own.

I might add I am happy the institute flourishes and wish all those involved with it, the very best.

Luke's daughter at Portlick Castle

Luke at Portlick Castle

Portlick Castle from the air

Portlick Castle in 2016

Let’s talk about your poetry – when did that start?

Well actually it began when I was working in Foreign Affairs. When I became disillusioned with what I was doing, I began to type my poetry up. I was caught by the Director who said ‘What’s that? That’s not a submission is it?’. I said ‘I’m trying something experimental sir’. That poem was published by The Canberra Times under the title ‘Room 3207’ – it was about my office space and not terribly kind. This could really be considered a resignation poem.

I continued writing poetry while on the ship going to Europe and the wireless operator would transmit them to The Canberra Times, who would then came back with an acceptance; the poem ‘Atlantic Crossing’ was published while I was sailing on the ship.

I continued in Italy. At this point I was living outside Perugia and Rita used to come out on the train, it was about an hours’ journey. I lived on my own in a small stone cottage in the hills near a town called Umbertidi, Città di Castello. In those days I paid $20.00 Australian or about 29 thousand lire a month rent. It was a 2-bedroom cottage on 2 floors, built by an Umbrian famer called Mezzaponte, which means ‘halfway over the bridge’. He was somewhat indecisive – he would spend a lot of time making a decision and then couldn’t make up his mind to act on it, so would turn around and go backwards.

Living there on my own I’d be reading copiously. I met American artists, and expatriate writers who lived close by, and they adopted me. One of the Americans, the wife of one of the painters, Anna McGarrell, was a poet. Anna gave me a lot of poetry to read and I just began writing poetry, initially as a way of filling in time.

Once I was doing the house renovations it became very much a spare time thing – and then Rita would come out on the weekends to distract me – she was still at school then, as they do a year more than we do here in Australia.

What were your subjects, what was the spark?

The spark I think was the Italian way of life; the food and family culture. I lived next door to farmers who very kind and adopted me as well. They said ‘you have got to come every Sunday for lunch. If you don’t turn up, we’ll come out and find you.’

So, I went there often for lunch and learnt to cook from Maria Ferrucci. Maria and her husband Pino - who was a tiny little man and she was a huge woman - he was a carpenter, they grew their own olives, made their own fresh pasta, had their own chickens and pigs, and I learnt to cook from her. They enjoyed me being in the kitchen because I’d be sitting there with the whole family; children, grandchildren, aunts and uncles, and they had these huge television sets in the kitchen in those days. Everyone would sit around watching the telly together. They would watch those nature programs David Attenborough would narrate and say to me ‘Luke, what is a giraffe and how big are they really?’ Then the eldest son, who was a bit of a know-all, and competing with me all the time, would get up and say ‘this is how big a giraffe is’ indicating by putting his fingers up against the television screen and then measuring out five or six centimetres high. I’d say ‘no, no, that’s not right – a giraffe wouldn’t be able to get into this room, its head would go through the ceiling’. So I became the authority in what size the animals on the nature television programs were.

This was how I paid for my Sunday tucker – and I was learning as much as I could from Maria, enjoying their company, and of course I also learnt to speak the dialect.

Can you remember the first poem you wrote, what it was about?

I’d have to go into my papers and look – it’s probably not a poem I’d be very happy about I suspect – oh, I remember, it was ‘Room 3207’ – and yes, it was published!

How long have you been writing poetry?

Seriously, since 1995, starting in Dublin, where I read my verse in pubs and cafes, and was published in Irish newspapers and journals, as well as the Irish Centre for Poetry Studies.

Have you seen any developments in what you are writing and how you are writing about any subject?

Of yes, there’s been a lot of development. Initially I wrote about Italy and the countryside there, as well as about the food culture and my life there. Then when I was in Ireland, I wrote about my life there in Dublin and about the castle I was restoring; there are quite a few poems about Dublin and Restoration. I then started to broaden out and write more generally. I’ve just written a poem about boats seemingly abandoned in bays around here (Pittwater). I’m going to call that one ‘Covid Bay’. No one appears to have been using their boats, most of them seem abandoned.

You have been widely published and had poems of yours sung by one of Florence’s leading Sopranos – when did that event happen?

That was a Reading with Florence Opera soprano Sarina Rausa in Florence in 2015. Sarina is Australian-Italian. Sarina was brought up near Melbourne on her parents’ potato farm and showed promise as a singer very early. Sarina won a scholarship to go to Europe and has ended up being the top soprano of the Florentine Opera Company.

I’ve written a poem about her singing, a short one, it has been published in Florence and in Australia.

Sarina Rausa is still living in Florence and singing and teaching singing now.

This Reading was held at the sculpture studio Romanelli; an immense room packed with sculpture by three generations of Romanelli’s - who worked for the Medici family and have sculptures on public display in Florence, Rome and other capital cities of Italy.

Raffaello Romanelli invited me to read to a selected audience of academics, artists, journalists and writers with Sarina Rausa of the Florence opera, who sang 8 poems of mine dedicated to the goddess Venus.

When I returned to Australia the Pacific Opera Company also sang some of my poems in the State Library of New South Wales. A very well-known Australian poet, Mark Treddenick, read my poems. I was gratefully in the audience – it was rather nice to be watching.

There have been numerous other instances, and places I read at annually, Manning Clark House in Canberra as one example.

Reading poetry is a one-to-one experience, quite intimate – if you had to nominate 3 of your poems from 10 to 15 years ago and current works that still resonate with you; what would these be and why do they still appeal to you?

It’s actually embarrassing how many poems I’ve written; I’ve been quite prolific and need to revise quite a lot still. There are several thousand now. With this second book, What Light Can Do, I will only have published 215 of them. In journals and magazines there have been 40 or more published and a dozen in Ireland.

There’s one that’s been published in magazines and books called ‘The Swallows of St. Peter’s Square’ that’s a favourite. Why?; it is quite beautiful in the Autumn to watch the swallows in Rome farewelling St. Peter’s square, and the poem deals with that.

Another poem would be ‘Bologna’, because this is about the food culture in Bologna and the people of Reggio Emilia, which is the province of Bologna. They are absolutely fun loving, food loving, life-living lovers. They are extraordinary people; the most extroverted people of all Italians, even more than the Roamns. Their food culture is extraordinary – these are the Italians who first started using sour cream in their sauces and are also those who invented the tortellini.

The tortellini in the poem Bologna refers to the legend of the inventor of this dish. The story goes that he was a chef in a pensione (a hotel) who was a bit of a voyeur who was fascinated by this incredibly beautiful woman, a courtesan, who was a guest and there to meet a nobleman. The chef went up and spied on them through the keyhole of the bedroom door, saw her naked, and was so smitten he raced back down to the kitchen to devise a pasta that would resemble her navel. The tortellini are what he invented, according to the legend.

Bologna.

Lord I am golden from drinking

Your famous Lambrusco

I’ve stared deep into all of your Saints’

Eyes; gorgeous Cecilia, modest Mary Magdalen

Trailing threads of gold through their dresses

The master Raphael painted, wondering blasphemously

If they were pink or golden on the other side.

Under slow golden light, under the arches

We ate tortellini, once fashioned after

The curls in a courtesans’ navel, spied through a tavern keyhole

And made by the chef, a mesmerised voyeur --

From butter, oil, eggs, flour and water ...

Now descending navels move about, creamily in my mouth

And my mind’s lascivious tongue slips over the curve of a belly

Down to a lower unbuttoning of life

I imagine I’m lying with her on the edge of the bed

Knowing the hungry eye watches, blinking lust through a keyhole.

Now some of the sweet and nutty Parma ham

Streaked with creamy ribbons of fat

Draped over split purple figs

Covering their luscious ruby insides ...

And cream spiced with truffles and Grana Padano

Slides in yellows over my tagliatelle --

I lift the strands, wrapped round my fork

As I anticipate, sniffing life’s pungent source.

My tongue swims on through voluptuous textures

As I juggle a last prayer to Mary and Altissima Cecilia

And also to our carissimo friend, Master Raphael;

Please forgive me Maestro, for my rather plain images

Of what you have already made magnificently famous...

Forgive me as well dear lord, my gastric promiscuity

Swallowing this platter of Emilian tortellini

Under your saintly alabaster gaze, under

Your patronage, under the drunken towers of our beloved Bologna.

Luke Whitington.

Coming back to Australia and your Australian themes – you had something included in the tribute to the life of Les Murray?

Yes, that was a poem titled ‘Bunya’, which was the town nearby where he lived, and this was a poem about his landscape.

Do you like writing landscape poems?

Yes I do; I’ve done a lot of those. Bunya is an Australian poem and there are others. I’d have to go back and check. My first book, ‘Only Fig and Prosciutto’, had four sections in it and they were about my farm in Australia and the Australian Bush, Italian landscapes, Ireland countryside and then Elsewhere. All of the first poems that I’m still attached to are in that book. So, this book involves my life in these different countries and a lot of the things I was doing, observing or learning.

You have been spending some time in Pittwater during this year’s lockdown?

Yes; I have been a guest in Antonia Hoddles’ studio at the top of her property in Lovett Bay. We occasionally cook up food together and I also try and help her with observations about her painting and she in turn gets to see early drafts of my work.

Do you like being in Pittwater?

I do and I don’t. That’s not necessarily due to Pittwater itself. There is, at the moment, a tremendous feeling of dislocation, which I think many people are feeling or experiencing. Even if they’re in their own homes, they’re still feeling dislocated as they’re isolated from things they’ve been used to doing for a long long time, and from other people they know of course. I feel that the media beat up, which was described to me by a poet as ‘Covid Fear Porn’, and the politicians’ daily lectures on Covid, have also had a negative effect in encouraging a hesitancy, and an anxiety in people’s attitudes and outlook.

I’m a bit of a nomad though; I’m used to moving. I live in Sydney, in Potts Point, I live in Canberra because I read poetry at Manning Clarke House, normally every year, and then I go to the farm down at Braidwood. I’m accustomed to always being on the move, so this lockdown has been a huge change for me. My parents used to do the same thing, so that’s where this need to move comes from. They were based in Sydney but had a farm in Dural, a farm near Canberra and subsequently at Braidwood. They would continuously get into the car and we would just drive off together, to wherever.

So, where feels like home to you?

I feel at home in all these places because I have friends in all these cities and towns.

But is there a place, a landscape, that your inner self responds to with an unexpressed sigh of relief when you go there because it gives you a connected sense of ‘home’?

The farm at Braidwood would be that place – I’ve written poems about the farm, they’re all in the first book.

That gave me a sense of coming home despite my mother having told me to sell it, before she died. I know she’d struggled there alone for years, so I can understand her telling me to ‘sell it, get rid of it!’.

I’m glad I held onto it for a number of reasons, also because it’s gone up in value. While I was overseas there were views I remembered from my teenage years, the smell of the gums in the Summer winds, the Mongarlowe river flowing all the way through there, kilometres of it winding on my western border, the forests I remembered of course on Mount Budawang, which we called ‘Mount Baldy’ because the loggers took all the trees from it when I was a kid. Now it’s completely reforested and no longer bald. Braidwood town I remember as a kid too; the kids I went swimming in the river with are all farmers about here. My neighbors, who have always been friends, have been farmers for 70 years; the Shoemark family, a lovely family, truly salt of the earth people.

Currajugg, Braidwood

What would you describe yourself as; a restorer of buildings, a poet, a farmer, a diplomat?

I would say, certainly not a diplomat. But I spent 27 years restoring Renaissance and Medieval buildings, I’m a published Poet and have been a Businessman, dealing in property mainly. I’ve also been a farmer. Which is a lot on your plate for a Poet to be – but I still manage to wear four hats.

What are your favourite places in Pittwater and why? – and you can’t say ‘Covid Bay’!

No; fine – we could call it ‘Paradise Lost Bay’. The natural beauty here is unquestionably stunning. I feel though, and I may not be too popular saying this - but I suspect there are too many moorings now and the concentration of boats, especially with all those masts without sails, is rather daunting. I find those bristling masts reminiscent of a razed landscape or leafless burnt trees after a firestorm. I think the MSB or possibly the council has overdone it with moorings because it’s difficult to see the foreshores anymore.

I have been told the council’s approach to the social connection factor for the people who live here makes it more difficult for their friends to visit, partly because there seems to be a focus on making it all pay instead of allowing people simply to live here and be visited by friends. It costs money for people to visit, both for transport and parking, which is not always available. Teenagers must have a terrible time because the ferry service stops at 7 o’clock. I clearly remembered trying to find a parking place right up the top of Church Point – there wasn’t a single ‘no parking’ sign so I felt secure, and there was no kerb, just grass running down to earth. I then came back to find a ticket for a fine of one hundred plus dollars - on the ticket it read ‘for parking on the kerb’.

I love the light on the water in Pittwater at several times of the day; different in the morning or in the middle of the day or in the evening, the light here is extraordinary. At the end of the day there’s a tide of crimson light that envelops all of the boats and that is really quite moving. I’ve taken several photographs of the sunsets here, just beautiful.

Sundown.

Yellow light sweeps the fenceline, scything low

Flooding toward the first trees – struck, bedazzled, frozen

Engulfing trunks and climbing branches equally

Bathed in this long, slow moment of the declining sun.

Everything is illuminated, the stretched branches exalt

And now reaching, become uplifted arms

Higher above against the sky their tendril-tips tremble delight

Slow motion in flowing leaves, leaves like golden sequins

Reflected, elongated, undulating above the blazing water

The trees bask their trunks and limbs benign

Aligned in curved attitudes of contentment.

Now let’s try to remove the leaves, the tips and slender bits

The arms, flesh-like; ease them

Gently away from the trunks

Leaving just the main artery of a tree

The stark, sketched upright, single arm of a tree.

Each tree is no longer a tree

It is a squiggle of a thing, flicked whimsically

A signal scrawled further back, now scribbling in the distance

And shifts quickly like some sticks twisting in a tumult of sunlight.

Shapes of foliage dishevelled, flung into something ephemeral

And as weightless as an unsettled autumn leaf.

Or like a runaway wheel’s spokes, spinning lines of light on the horizon

Or the last flailing ribbons of a distant shining hope.

We look at their far away exclamations, their proclaimed intensity

Is this a confession? – revelation of something we have perhaps forgotten --?

Or something else, somehow lost, a poignant loss --

Something somehow prophetic;

And now does the last light

Flowering behind the crests of hillsides

Like a soul’s golden heart

Lift us effortlessly, far away beyond these trees? --

Beyond this glowing image

These sketched figments of such fragile, elusive life? --

And with the dusk wind we rise, to swirl

And stream away -- at heart with those departing leaves

The light fleeing ahead, flowing beyond this flickering of time.

Luke Whitington.

Morning Bay Sunrise, Pittwater, November 17, 2021 - photo by Luke Whitington

What is your ‘motto for life’ or a favourite phrase you try to live by?

The family motto, on my mothers’, Drake Brockman side, is; ‘to be and not seem to be’.

That’ll do me.

I also like;

‘’While you are thinking about how much you have done or are doing for others, and possibly feeling a bit sorry for yourself— try and remember how much others have done and are still doing for you.’’

Wise words from my stepfather, Major-General Paul Cullen. RIP

Notes

Ireland's records show; 67 Pleasants Place, Dublin; 1993 Pleasant Factory, Creative Space, Dublin; exh: "For Your Pleasure." 1993 Pleasants Factory, Dublin; exh: "Una Sealy."

Richard Smallpeice "Dick" Whitington (30 June 1912 – 13 March 1984) was an Australian first-class cricketer who played for South Australia and after serving in World War II, represented the Australian Services cricket team, which played in the Victory Tests. He became a journalist, writing as R. S. Whitington.

Richard Smallpeice "Dick" Whitington (30 June 1912 – 13 March 1984) was an Australian first-class cricketer who played for South Australia and after serving in World War II, represented the Australian Services cricket team, which played in the Victory Tests. He became a journalist, writing as R. S. Whitington.

Whitington was born in the Adelaide suburb of Unley Park, the younger son of businessman Guy Whitington (c. 1880 – 5 February 1954) and a member of the distinguished Whitington family of South Australia. He attended Scotch College, Adelaide, before studying law at the University of Adelaide and becoming a lawyer.

He married Alison Margaret "Peggy" Dale on 19 December 1939; they divorced in 1942. He served in the Middle East as a captain with the 2/27th Battalion of the Second AIF.

Whitington began his state cricketing career for South Australia at the age of 20 in November 1932 under the captaincy of Victor Richardson as an opening batsman. He was a regular member of the South Australian side until World War II, playing 36 matches and scoring 1728 runs at an average of 30.85, with three centuries. His highest score for South Australia was 125, which he scored twice against Queensland: in 1936–37, batting at number three, he was the highest scorer in a match that South Australia won by 112 runs; in 1938–39, opening, he put on 197 for the first wicket with Ken Ridings in a ten-wicket victory.

CRICKETERS REACH ENGLAND

Hassett, Whitington

A cable message from England yesterday announced the arrival of Lindsay Hassett and R. S. Whiting-ton as members of the AIF. It was recently reported that a team of Australian cricketers was being built up, something on the lines of the AIF team of the last war. Hassett (member of the last Australian Eleven and one of the most brilliant batsmen of the day) and Whiting-ton (a talented South Australian) are likely to join those RAAF players who have been shaping so well against leading English players. Keith Miller (South Melbourne and Victoria), Eddie Williams (Fitzroy and Victoria), Cristofani (St Kilda and NSW), McDonald (HawthornEast Melbourne), and Gordon Carl-ton (Essendon) have been among the shining lights. CRICKETERS REACH ENGLAND (1944, September 1). The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 - 1957), p. 11. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article11359115

He resumed his first-class career after his war service, taking part in the Australian Services tour of England in 1945, the tour of Ceylon and India, and the short tour of Australia. He played 18 matches on the three tours, scoring 1054 runs at an average of 35.13. He scored one century, 155, in the second of the three matches against an Indian XI: opening, he put on 218 in 175 minutes for the second wicket with Jack Pettiford. In his final first-class match, the last match of the tour, he made 84, the Services XI's top score, in the draw against Queensland.

Whitington was a prominent journalist and writer, usually writing as "R. S. Whitington", and he balanced this work with his playing career until his retirement. He was known for his collaborations with Services XI teammate Keith Miller; the pair wrote many books together. Whitington wrote for the Sydney Sun. He was sports editor and roving Test reporter for Consolidated Press, owned and managed by the Packer family. For five years, from the late 1950s to the early 1960s, he worked in South Africa. He wrote numerous books on cricket, many of them prefaced by Sir Robert Menzies, and in later years, the official biography of Sir Frank Packer, and a history of Australian cricket.

Death Of Mr. Guy Whitington

Mr. Guy Whitington, who was well known in Adelaide business circles, died at his home at North Adelaide on Friday, aged 73. Mr. Whitington was a former partner and director of Lion Timber Mills. He was the fourth son of Mr. Peter Whitington, formerly Commissioner of Audit, and grandson of Mr. William Smallpiece Whitington, who came to SA in 1840 from Guildford, England, in his own ship, New Holland. In 1899, after education at Way College and Malvern College, Adelaide, Mr. Whitington joined Lion Timber Mills. He was taken into the partnership in 1923, and was made a director in 1929. At the time of his death he was employed by the National Mutual Life Association. Rose Lover Mr. Whitington was a great lover of roses and birds, and for many years was one of Adelaide's best known pigeon fanciers and show exhibitors. He was a brother of the late Mr. Ernest Whitington, who conducted a column in 'The Advertiser' under the pseudonym of 'Rufus.'

He is survived by a widow and two sons— Mr. Alexander Peter Whitington, of Adelaide, and Mr. Richard Smallpiece Whitington, of Sydney. The latter son is a former SA cricketer, and author of several books on cricket. The funeral at West Terrace Cemetery yesterday was private. Death Mr. Guy Whitington (1954, February 9). The Advertiser (Adelaide, SA : 1931 - 1954), p. 3. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article47565694

GALLERIA ROMANELLI

Borgo San Frediano 70, 50124 Firenze, Italy

An authentic Sculpture Studio where the same Family keeps making and trading sculptures after two centuries of activity, blending tradition with contemporary taste. The studio boasts a vast collection of models ranging from classical and Renaissance pieces, to neoclassical and contemporary masterpieces. Among these are Romanelli creations, which form part of an exclusive collection held by the Gallery. Traditional and modern techniques combine to create unique pieces of art: our bronzes are cast according to the ‘lost-wax’ method and accurately chiselled; our marble sculptures are hand carved out of the finest Carrara Marbles. The inhouse sculptor is Raffaello Romanelli, who represent the 5th generation of Romanelli sculptors down the male line. He works on personal pieces and supervise the creation of every product that comes out of the studio. Clients are welcome to discuss bespoke projects and have advice on finest solutions. The Gallery caters for art lovers, collectors, architects and designers searching for unique artworks. The Studio opens its doors to all visitors interested in learning the sculpting techniques. Short courses, bespoke projects and family workshops are offered for students and visitors alike.

In 1829 Bartolini bought and restored an ancient ecclesiastical structure in Borgo San Frediano; here it’ll be surrounded by stonemasons, rough-knives, models and helpers including its favorite pupil Pasquale Romanelli. The latter, after the death of the master, will take over the Studio in San Frediano, now home to the Romanelli’s Gallery. In 1830 he was commissioned the monument of the Russian Prince Nicolai Demidoff: for to many contrasts between the artist and the client and repeated delays in the completion of the work, this is remained incomplete in his death. It was the task of his pupil and continuator Pasquale Romanelli to conclude the work now placed in the homonymous Florentine square on Lungarno. From 1939 he became teacher at the Accademia of Belle Arti in Florence and fought to spread a style of sculpture more related to the naturalistic vitality rather than academic ideals. The peak of his fortune was reached with La fiducia in Dio (1835) for the Marchesa Rosina Trivulzio Poldi Pezzoli, commissioned by her following her husband’s disappearance. The work was immediately celebrated as one of the masterpieces of modern sculpture for the extraordinary ability of the artist to make in marble the tenderness of the adolescent forms of the young woman, gathered in confidant religious meditation. Bartolini died on 20 January 1850 in Florence and was buried in the chapel of San Luca in the Basilica of SS. Annunziata, in the same crypt where the remains of Pontormo and Benvenuto Cellini rest.

RAFFAELLO C. ROMANELLI (1980)

The human figure is the nucleus of Raffaello’s work and the natural proportions of the human body are a continual source of inspiration for him. Each piece owes its beautiful form to his pursuit of realistic representation. His forte is portraiture: he is meticulous about modelling from life which enables him to capture the facial form, a myriad of expressions and consequently the personality of his subject. This is the secret behind the expressive nature of his works. Raffaello has always had a special affinity with art, he nourished his eyes with the examples of his ancestors and breathed the air of a studio as a child, in contact with the sculptors whose ideas and knowledge he gathered. He went on to undertake

classical training from Charles H. Cecil in Florence, where he mastered the technique of drawing and sculpting from life. Today the ancient family studio at Borgo San Frediano is under his care, a place of work and inspiration. Here he gives life to his personal projects and receives his international clients. His works ranging from bronze limited editions to being carved by hand out of marble. Today he teaches courses of sculpture allowing a continuity of the technique and knowledge acquired in the family and in his experiences allowing the aspiring sculptors to learn the skills necessary for the creation of a work.