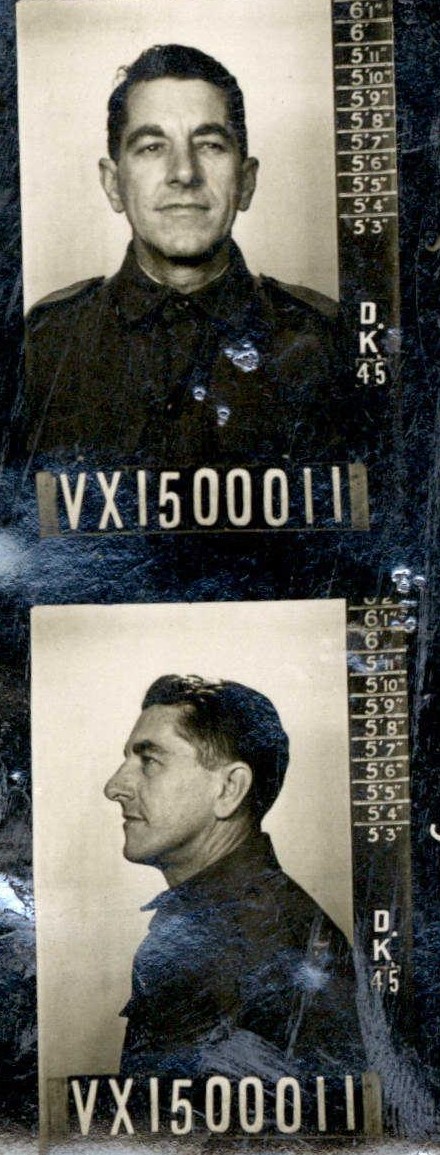

Gerald Joseph McPhee - a World War II 'M' special Unit member: Remembrance day 2022

Remembrance Day Commemorative Services will take place at local RSL's on Friday November 11th, deatils below.

In previous history page, Brock's The Oaks - La Corniche From 1911 to 1965: Rickards, A Coffee King, A Progressive School, A WWII Training Ground, it became apparent that a Mosman family bought the bulk of the land and cottages associated with the by then 'La Corniche' during its short time as 'Quest Haven' and during the period this land and its buildings were utilised as a training centre during World War Two.

Some of the peculiarities that showed up during widower Mr. Gerald McPhee Snr.'s dealings with the Army during that period are brought into starker relief when you consider his son, Gerald Joseph McPhee was serving in several very dangerous missions in New Guinea during that time as part of 'M' Special Unit. He had been transferred to 'M' Special Unit October 22nd, 1943. His previous Unit was the Independent Company - Reinforcements, which was the first commandos unit of the Australian Army.

He was in his early 20's at the time.

In 1943, M Special Unit was formed as a successor to the Coastwatchers, with the role of the unit focused on gathering intelligence on Japanese shipping and troop movements. To achieve this mission, small teams were landed behind enemy lines by sea, air or land insertion. This was in contrast to its counterpart, Z Special Unit, which became well known for its direct-action commando-style raids, although it is recorded in G J McPhee's records that M Special Unit members also undertook offensive actions.

'M' Special Unit was was a joint Allied special reconnaissance unit, part of the Services Reconnaissance Department (SRD), in the South West Pacific theatre of the Second World War. A joint Australian, New Zealand, Dutch and British military intelligence unit, it saw action in New Guinea and the Solomon Islands between 1943–1945, against the Empire of Japan.

Z Special Unit was a joint Allied special forces unit formed during the Second World War to operate behind Japanese lines in South East Asia. Predominantly Australian, Z Special Unit was a specialist reconnaissance and sabotage unit that included British, Dutch, New Zealand, Timorese and Indonesian members, predominantly operating on Borneo and the islands of the former Dutch East Indies. The unit carried out a total of 81 covert operations in the South West Pacific theatre, with parties inserted by parachute or submarine to provide intelligence and conduct guerrilla warfare. The best known of these missions were Operation Jaywick, which was launched from Refuge Bay, and Operation Rimau, both of which involved raids on Japanese shipping in Singapore Harbour; the latter of which resulted in the deaths of 23 commandos either in action or by execution after capture.

M Special Unit was disbanded at the end of the war on November 10th, 1945.

This year, 2022, a number of Commemorative Services have taken place to mark the 80th anniversary of the Battle of Guadalcanal and the 80th anniversary of the sinking of HMAS Canberra, as well as the 80th anniversary of the Kokoda Track campaign. Approximately 625 Australians were killed and more than 1,600 wounded in the four-month battle along the Kokoda Track in 1942.

On November 3rd, 2022 the NSW Government announced it has designated November 3, as NSW Kokoda Day to officially acknowledge the Kokoda campaign of the Second World War.

Premier Dominic Perrottet announced this would be an annual day of acknowledgement for the veterans of Kokoda, to recognise their bravery and efforts in New Guinea.

“Having walked the track myself, it is important we, and future generations, mark the bravery and sacrifices of those who served there” Mr Perrottet said.

“Our troops had to wade through mud, fighting off insects and infection, before encountering some of the most brutal battles of the Second World War.”

“Establishing 3 November as a NSW day to honour the service of our veterans from Kokoda will ensure their efforts and sacrifice will not be forgotten.”

Minister for Transport, Veterans and Western Sydney David Elliott made the announcement today at the Kokoda Track Memorial Walkway.

“On 2 November 1942, Australian troops reclaimed the Kokoda village after four months of brutal jungle warfare. The following day, the Australian flag was raised.” Mr Elliott said.

“On the 80th anniversary of this occasion, we remember the strength and resilience of all those who served along the Kokoda Track and it is wonderful to now have this day recognised in our NSW calendar.”

NSW Kokoda Day will last as a yearly acknowledgement of the contributions made by Australian men and women of the Kokoda Track and also acknowledge the sacrifices of their families.

The Kokoda Track Memorial Walkway in Concord is a living memorial that gives the people of NSW a greater sense of what Australian troops experienced in New Guinea. It is a place for commemoration and reflection for veterans and the community.

“With the number of Australians who served in the Second World War sadly dwindling, it is important that the residents of NSW have memorials that can continue to educate the younger generation on significant events in Australia’s history, like the Kokoda Track campaign.” Mr Elliott added.

You can get more information on the Kokoda Walkway website

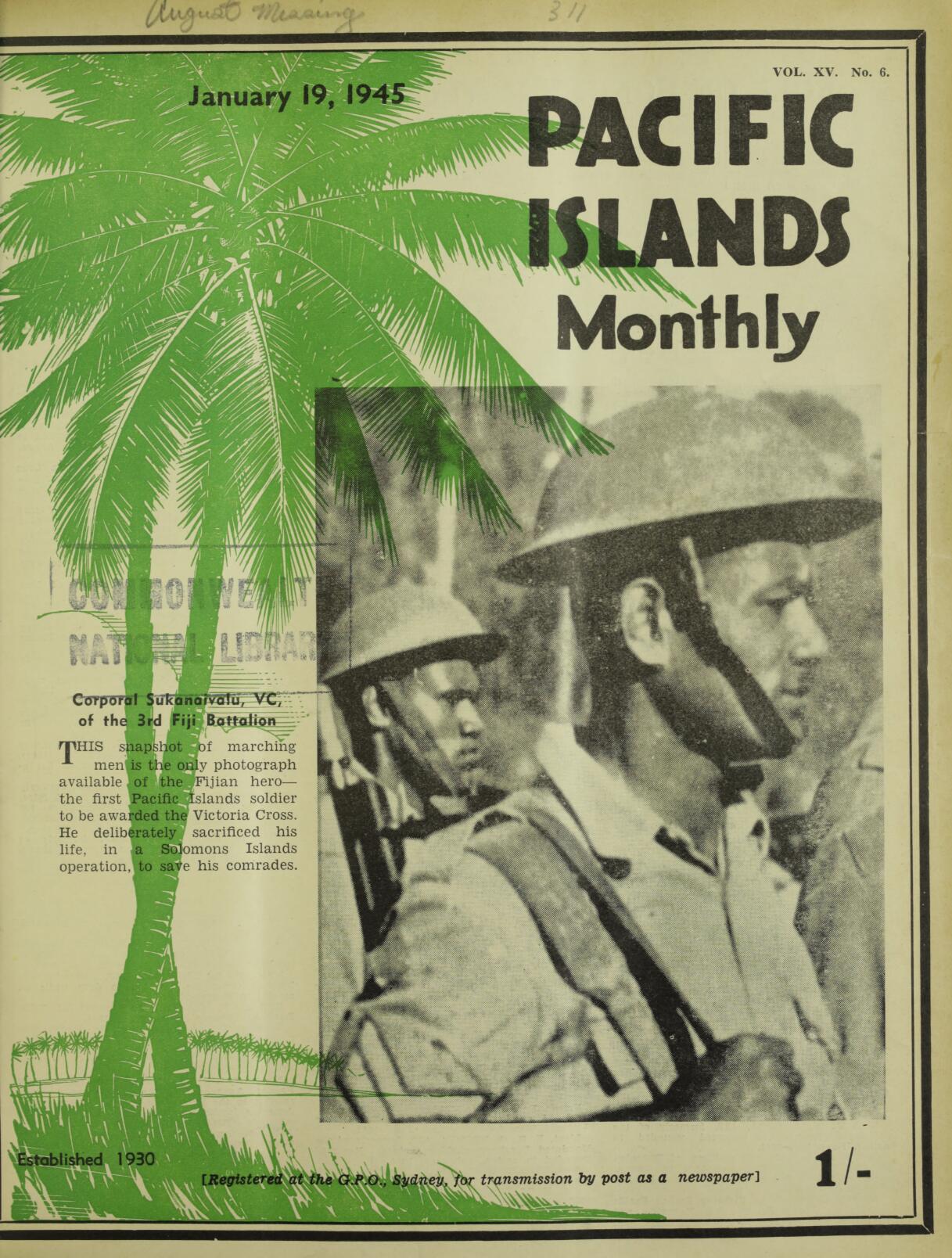

Commemorative Services this year have also included honouring Solomon Island Scouts and Coast Watchers. In August 2022 United States Ambassador to Australia, Caroline Kennedy, attended a Service at the Solomon Scouts and Coastwatchers Memorial. Ambassador Kennedy's attendance had a personal touch as she was also able to pay a tribute to those who had saved her father's life.

TRANSCRIPT: Ambassador Caroline Kennedy’s Remarks at the Solomon Scouts and Coastwatchers Memorial

August 7, 2022 – Honiara, Solomon Islands

AMBASSADOR KENNEDY: Good morning.

Mr. Veke, Ministers of the Crown, Ambassadors, distinguished guests, our hosts from the Solomon Islands, Sir Bruce Saunders, and those who work on this memorial.

Mr. Kenilorea, thank you for those moving remarks and for your own family’s distinguished public service.

Minister Conroy, Vice Admiral Hammond, Minister Oniki, General Yamazaki, Minister Henare, it’s great to be with you today on this memorable anniversary.

I’m especially honored to accompany Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman, Deputy Commander of INDOPACOM General Sklenka, Commander of Marine Corps Forces Pacific General Rudder, and diplomatic and defense colleagues from the United States, Australia, Japan, and New Zealand to mark this anniversary.

As we reflect on the battles that took place on these lands and in these waters 80 years ago, we honor the courage of the Solomon Scouts and Coastwatchers who made a critical contribution to turning the tide at Guadalcanal.

Solomon Islanders risked their lives to support the Allied effort.

Many joined in the fight, lending their superior knowledge of the local terrain and their expertise in jungle fighting.

They stayed behind Japanese lines at personal risk to their own safety and that of their families.

The information they gathered was invaluable to the Allied effort during the Guadalcanal campaign.

Because of the selfless service and sacrifice of the Solomon Scouts and Coastwatchers, the Allies were able to hold Guadalcanal.

And because of Guadalcanal, the Allies achieved victory in the Pacific.

While we all owe a debt of gratitude to the Solomon Islanders who risked their lives during the Pacific Campaign, my family and I owe a personal debt of gratitude to two Solomon Islander Scouts — Biaku Gasa and Eroni Kumana – who saved my father’s life.

Thanks to them, he and his crew survived the sinking of PT-109 and were able to return home and eventually run for President.

His experiences here made him the man and the leader that he was, just as the experiences of so many others shaped the men and women they would become.

It resolved him to seek a more peaceful and just world, and he gave his life for his country.

I’m deeply touched to be here today, knowing that I might not be here if it were not for Biaku Gasa and Eroni Kumana.

And I’m not alone in feeling this way. Countless Americans and Allied families have Solomon Islanders to thank for their survival.

We’re here today not only to express our gratitude to those who sacrificed during the war, but also to those who established peace and worked for the years and decades that followed to bring our nations closer.

I look forward to returning to Solomon Islands with my children and showing them this part of our family history – which is so closely intertwined with this country – and telling them about the partnership we’ve shared with Solomon Islanders in years since the war.

It’s our way to honour those who came before us and to work and do our best to leave a legacy for those who follow.

Thank you.

Ambassador Caroline Kennedy, the United States ambassador to Australia, meets with John Koloni and Nelma Ane, children of those who saved her father, at a ceremony marking the 80th anniversary of the battle of Guadalcanal. Photographs: US Embassy Australia

This had been preceded by a wreath laying ceremony at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra:

Ambassador Caroline Kennedy’s Meeting with Australian Coastwatchers at the Australian War Memorial

July 28, 2022

Ambassador Caroline Kennedy and General Mark Milley, Chairman of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, met with two Australian veteran Coastwatchers and their family members at the Australian War Memorial yesterday. The Ambassador reaffirmed the strength of the U.S.-Australia alliance and expressed her gratitude for the service and sacrifice of Australians during World War II, highlighting the Coastwatchers, who played a critical role in rescuing President John F. Kennedy after his patrol torpedo boat was destroyed.

Ambassador Kennedy met Ms. Eve Ash, daughter of Australian World War II veteran Mr. Ronald (Dixie) George Lee, and Mr. Tom Burrowes, son of veteran Mr. James Burrowes OAM, at the Australian War Memorial. Mr. Lee and Mr. Burrowes joined the meeting virtually from the U.S. Consulate General in Melbourne.

In their meeting, Ambassador Kennedy said “It was a great honor to meet two Australian Coastwatchers, who played an essential role in keeping the region secure during World War II. I owe personal gratitude to an Australian Coastwatcher and two Solomon Islander scouts who saved my father’s life. These men represent the best of their generation and are an amazing example of the bonds of the U.S.-Australia alliance.”

“I was deeply honored to participate in a wreath-laying ceremony with Ambassador Kennedy and meet a few Australian Coastwatchers. The U.S-Australia alliance remains just as strong as when we fought side-by-side more than 70 years ago. The World War II generation of Americans and Australians bequeathed us a set of freedoms, and we have an obligation today to uphold their sacrifices,” said General Mark Milley, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the highest ranking military officer in the United States.

“The event was a very special and personal acknowledgement by Ambassador Kennedy and the US government of the role we had as Aussie Coastwatchers eight decades ago. I am proud at 98 to meet Her Excellency and share Coastwatcher stories. The time I spent in the Solomons and other locations as a Coastwatcher is as vivid today as it was then. It has been an honor to participate in this memorial event,” Australian World War II veteran Mr. Ronald (Dixie) George Lee.

“’It was an amazing experience to meet with Ambassador Caroline Kennedy and extremely pleasing to speak with her during the commemorative wreath-laying. As a Coastwatcher, I have long been aware of the role played by the Australian and Solomon Islander Coastwatchers Reg Evans, Biuku Gasa and Eroni Kumana in rescuing then Lieutenant John F. Kennedy and his crew after their Patrol Torpedo Boat was cut in two by a Japanese destroyer. So I was honored to receive the Ambassador’s kind acknowledgement of our Coastwatching role in the war and recognition of our rescue of the future President,” Australian World War II veteran Mr. James Burrowes OAM.

Ambassador Kennedy presented Ms. Ash and Mr. Burrowes with replicas of the coconut that President Kennedy used to send a rescue message following the destruction of his patrol torpedo boat, PT-109.

Following their meeting, Ambassador Kennedy, Ms. Ash, and Mr. Burrowes, along with Chairman of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff General Mark Milley, toured the Memorial Commemorative Area.

“Our wonderful new U.S. Ambassador Caroline Kennedy has shone a very personal light on the special role of Australian Coastwatchers in World War II. I was privileged to meet her and General Milley and to lay a wreath on behalf of my father, one of the last surviving Coastwatchers. The tour of the Australian War Memorial was very moving. No doubt Ambassador Kennedy will strengthen and bring warmth to the close bond between our two countries,” Ms. Eve Ash, daughter of Australian World War II veteran Mr. Ronald George “Dixie” Lee.

“I am truly humbled to represent my Coastwatcher father Jim Burrowes on this specific commemoration to the Coastwatchers with our U.S. allies and with such a personal connection. The bravery and sacrifice of the Coastwatchers is inspiring to the next two generations of Australians who have enjoyed relatively peaceful enjoyment and prosperity. We express our deep gratitude and indeed, I dips me lid! And Lest We Forget,” Mr. Tom Burrowes, son of veteran Mr. James Burrowes OAM, at the Australian War Memorial.

Ambassador Kennedy, General Milley, Ms. Ash, and Mr. Burrowes then participated in the Last Post Ceremony and laid a wreath at the Pool of Reflection.

Ambassador Kennedy’s engagements at the Australian War Memorial reflect Australia’s status as a vital ally, partner, and friend of the United States.

“The U.S.-Australia alliance plays a vital part of promoting peace and stability in the Indo-Pacific region and around the world. I look forward to working to advance our alliance during my time as Ambassador.” – Ambassador Caroline Kennedy

The Coastwatchers, also known as the Coast Watch Organisation, Combined Field Intelligence Service or Section C, Allied Intelligence Bureau, were Allied military intelligence operatives stationed on remote Pacific islands during World War II to observe enemy movements and rescue stranded Allied personnel. They played a significant role in the Pacific Ocean theatre and South West Pacific theatre, particularly as an early warning network during the Guadalcanal campaign.

When the Japanese overran the Gilbert Islands in 1942, 17 New Zealand coastwatchers were captured. Imprisoned at Tarawa, they were executed by the Japanese in October 1942 following an American air raid.

In early November 1942, two coastwatchers named Jack Read and Paul Mason on Bougainville Island radioed early warnings to the United States Navy about Japanese warship and air movements (citing the numbers, type, and speed of enemy units) preparing to attack the US Forces in the Solomon Islands.

Born in Sydney on September 26th 1921 to Gerald Joseph and Mary McPhee, G J Jnr. came from a long standing tradition of farming families on both sides of his parentage. On December 3rd 1935, when Mary McPhee is recorded as the purchaser of the La Corniche 9 acres of lands and buildings, her husband's occupation is listed as 'retired Grazier'.

Gerald had been born in 1880, the second son of James John and Anne McPhee. Mary was the fourth daughter of Maurice and Hannah Mahoney. Her father was a farmer who passed away in 1887, leaving his wife to care for four daughters.

Gerald McPhee married Mary Kenny in 1917. Mary was already a widower and mother to a daughter, so there were no big announcements of their marriage in the local country newspapers, as had been the case with so many other community events. A simple record found is:

Personal Notes. — The engagement is announced of Mr. Gerald McPhee of Trangie, second son of Mr. J. McPhee "Copperhannie" Trunkey, and Mary, youngest daughter of Mrs. Mahoney "Aidar" Lambert St. and widow of the late A. Kenny. The marriage is to take place very early in the new year. The youthful bride-elect has already received many congratulations and expressions of good will for her future happiness. REMARKS (1917, November 7). National Advocate (Bathurst, NSW : 1889 - 1954), p. 1. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article158631918

The couple had two children, Anne, born in 1918, the birth registered at Bathurst, and Gerald Joseph. They were living at Mosman by then, Gerald the Grazier having decided to work in Real Estate, focussing at first on Mosman properties. Mary still visited her mother and other relatives in the country:

At the week-end Dr. and Mrs. Harris had a visit from Mrs. Gerald McPhee of Trangie, who, with her daughter, Betty, called here on the way to Sydney. Mrs. Harris and Mrs McPhee are sisters. Personal (1923, October 23). National Advocate (Bathurst, NSW : 1889 - 1954), p. 3. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article158677798

His father, who had moved to Sydney around the same time, passed away here after an accident in 1926:

MOTOR FATALITY

MR. J. J. McPHEE THE VICTIM.

The very regrettable news came to Cowra on Tuesday that Mr. James John McPhee, father of Mr. J. P. McPhee, of Cowra, had been knocked down by a motor lorry at Mosman that afternoon, and died shortly after being admitted to the Mater Misericordiae Hospital at North Sydney. The deceased gentleman, who had reached the ripe old age of 88 years, had resided for a considerable period at Copperhannia, Trunkey, and was well and favorably known in Cowra, having frequently visited here. For the past five years he had lived with his only daughter, Mrs. Deakin, wife of Dr. Deakin, at Mosman.

The late Mr. McPhee was a native of Ireland, but came to Australia when a mere child. At the point where the accident happened the street is being done up and only a narrow portion of it is open for traffic. Mr. McPhee had gone across for a paper and was re-turning when the lorry struck him. Rev. Father O'Donnell had also been for his paper and was quickly with Mr. McPhee, and had him conveyed to the Hospital, where he was admitted. The mortal remains of the deceased gentleman were buried at the Northern Suburbs cemetery, Rev. Fathers Murphy, O'Don-nell, and MacDermott officiating at the graveside. The late Mr. McPhee was a pastoralist, and for some years was a chairman of the Stock Board, and a member of the Land Board in the Carcoar district. He was also one of the first Shire Councillors at Rockley. He leaves four sons, Dr. V. J. Mc-Phee, of Macquarie Street and Rush-cutter's Bay; Messrs. J. P. McPhee, chemist, of Cowra; Gerald McPhee, pastoralist, lives at Mosman; and Jas. McPhee, pastoralist, of Orange. His only daughter is Mrs. Deakin, wife of Dr. Deakin. MOTOR FATALITY (1926, November 19). Cowra Free Press (NSW : 1911 - 1937), p. 9. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article262034292

McPHEE -November 16, 1926 at Mater private hospital, North Sydney, result of accident, James John beloved father of John, Gerald, May, James and Vincent aged 88 years, late of Copperhannia Trunkey. RIP. Family Notices (1926, November 17). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 14. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article16328760

Mr. James John McPhee.

One of the oldest and most respected residents of the Abercrombie district, in the person of Mr. J. J. McPhee, passed away recently at the age of 89. His early years were spent in Rockley, and after travelling a great part of N.S.W. he settled at Copperhania, in the Abercrombie Mountains, with wife (nee Miss Anne Mc-Laughlin, of Sodwalls), and engaged in pastoral pursuits until the last eight years of his life, which he spent with his daughter at Mosman. He was an active member of the Carcoar District Land Board for 20 years, and a member of the Carcoar Stock Board for over 30 years, part of the time being chairman. When shire councillors were appointed he was amongst the first to be elected to the Rockley Council. His wife predeceased him by 22 years, and he is survived by four sons — John (chemist, Cowra), Gerald (retired grazier, Mosman), James (stock agent, Orange), Dr. Vincent (Macquarie-street, Sydney), and one daughter, the wife of Dr. Deakin (Mosman). His only surviving sister Mrs. McLaughlin, lives in North Sydney. These with 22 grandchildren and a large circle of old friends, mourn their loss. He was a man charitable in thought, word and deed, and an exemplary Catholic— R.I.P. Mr. James John McPhee. (1927, February 3). The Catholic Press (Sydney, NSW : 1895 - 1942), p. 37. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article107973731

Their mother passed away soon after their parents bought La Corniche and its associated cottages, leaving their father in charge of meeting the payments for the mortgage they had had to take out. Records found in the National Archives of Australia indicate the small amounts of £ they received for renting the premises to the Quest Haven school just covered these. Mary was just 52 when she died.

McPHEE.-January 11, 1938, Mary, beloved wife of Gerald Joseph McPhee, and loving mother of Betty, Ann, and Gerald. Requiescat in pace. Family Notices (1938, January 12). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 16. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article17421949

McPHEE. — The Relatives and Friends of Mr. GERALD JOSEPH McPHEE and FAMILY, of No. 9 Prince Albert Street, Mosman, are kindly Invited to attend the Funeral of his dearly beloved wife and their mother, Mary, which will leave our Private Mortuary Chapel, 563 Miller Street. North Sydney. THIS WEDNESDAY, at 2.30 p.m., for the Northern Suburbs Cemetery. Family Notices (1938, January 12). The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW : 1931 - 1954), p. 13. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article247394232

Alberta Mary Kenny, Mary's daughter with first husband Albert Kenny who died the same year they were married, passed away in 1941, just 27 years of age.

KENNY.—May 7, Alberta Mary, daughter of Bert Kenny (deceased), and Mrs. G. McPhee (deceased). Family Notices (1941, May 17). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 12. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article17745341

Anne went on to become a nurse, while Gerald Joseph the son of G J McPhee went into advertising prior to enlisting to serve in World War II.

Doctors And Nurses

The medical profession has never used its influence to seek an Improvement in nurses' living and working 'conditions. In view of the undisputed loyalty and co-operation shown doctors by nurses, it is to be regretted that the medical profession as a whole is quite indifferent to the efforts of the closely allied nursing profession to obtain satisfactory working conditions living conditions and remuneration.— Anne McPhee, Mosman. Doctors And Nurses (1946, July 4). The Sun (Sydney, NSW : 1910 - 1954), p. 4 (LATE FINAL EXTRA). Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article231583948

Gerald McPhee first enlisted on the 29th of November 1939 at Paddington, aged 18 years and 4 months, listing his occupation as 'Printing Salesman'. He was put into the 1st Cavalry Division, Sigs.(N80453)

Following the demobilisation of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) that had been raised during World War I, Australia's part time military force, the Citizens Force, was reorganised in 1921 to perpetuate the AIF's numerical designations. At this time, the 1st Cavalry Division was raised alongside a second cavalry division and four infantry divisions. The 1st Cavalry Division consisted of the 1st, 2nd and 4th Cavalry Brigades. The 1st was based in Queensland, while the other two were formed in New South Wales. The division's headquarters was in New South Wales.

At the outbreak of the Second World War, the 1st Cavalry Division was allocated to the defence of coastal New South Wales. As part of defensive measures, the 1st and 2nd Infantry Divisions were tasked with defending Newcastle and Sydney, while the 1st Cavalry Division assumed the role of command reserve, based around Narellan.

Gerald then had to go through reenlisting again, as a 21 year old, on October 1st 1941, into the AIF. He was still in the 1st Cavalry Division - Signals, and was a member of this Unit when Darwin was bombed in February 1942.

On July 20th 1942 he was 'marched out to G.D.D. and to School of Guerrilla Warfare, Foster, Victoria.' Two days later he was having an x ray of his 4th right metacarpal(ring finger). A fracture of the fourth and/or fifth metacarpal bones transverse neck secondary due to axial loading is known as a boxer's fracture. Foster, Victoria, is a dairying and grazing town 174 kilometres south-east of Melbourne.

His designated Unit was now the 3rd Australian Armed Division

He was then enlisted in the AMF in November 14th, 1942, soon after turning 21, the then legal age for enlistment. He listed his religion as Church of England despite affirmed Catholic relatives on both sides of his parents families. This time he enlisted at Foster stating he had previously done military service as an Assistant Sergeant in the 1st Australian Motor Division - Signals (N80453).

He had become part of the Independent Company - Reinforcements.

The 1st Independent Company was one of twelve independent or commando companies raised by the Australian Army for service in World War II. Raised in 1941, the 1st Independent Company served in New Ireland, New Britain and New Guinea in the early stages of the war in the Pacific, taking part in a major commando raid on Salamaua in June 1942. Having lost a large number of men captured by the enemy as well as a number of battle casualties, the company was withdrawn from New Britain later in 1942. The company was subsequently disbanded, with its surviving members being transferred to other commando units, and it was never re-raised.

By January 1943 he was engaged in 'jungle warfare training'. By February 1943 he was off to Queensland prior to heading into New Guinea.

He then transferred into the AIF on March 8th 1943 [NX1515110] and then into the 1st Australian Commandos on August 25th, 1943 and was now part of the 'M' Special Unit on October 22nd, 1943.

Described as 5 feet 7 1/2 inches tall with grey eyes and dark hair, much of his official War Record is filled with blanks of course - long months where he was obviously engaged in operations behind the lines. These documents do record he was engaged in 'Special Duties', was evacuated to Berrima District Hospital on May 21st 1944 for an appendicitis operation but had re-joined his 'Unit' by June 22nd, 1944.

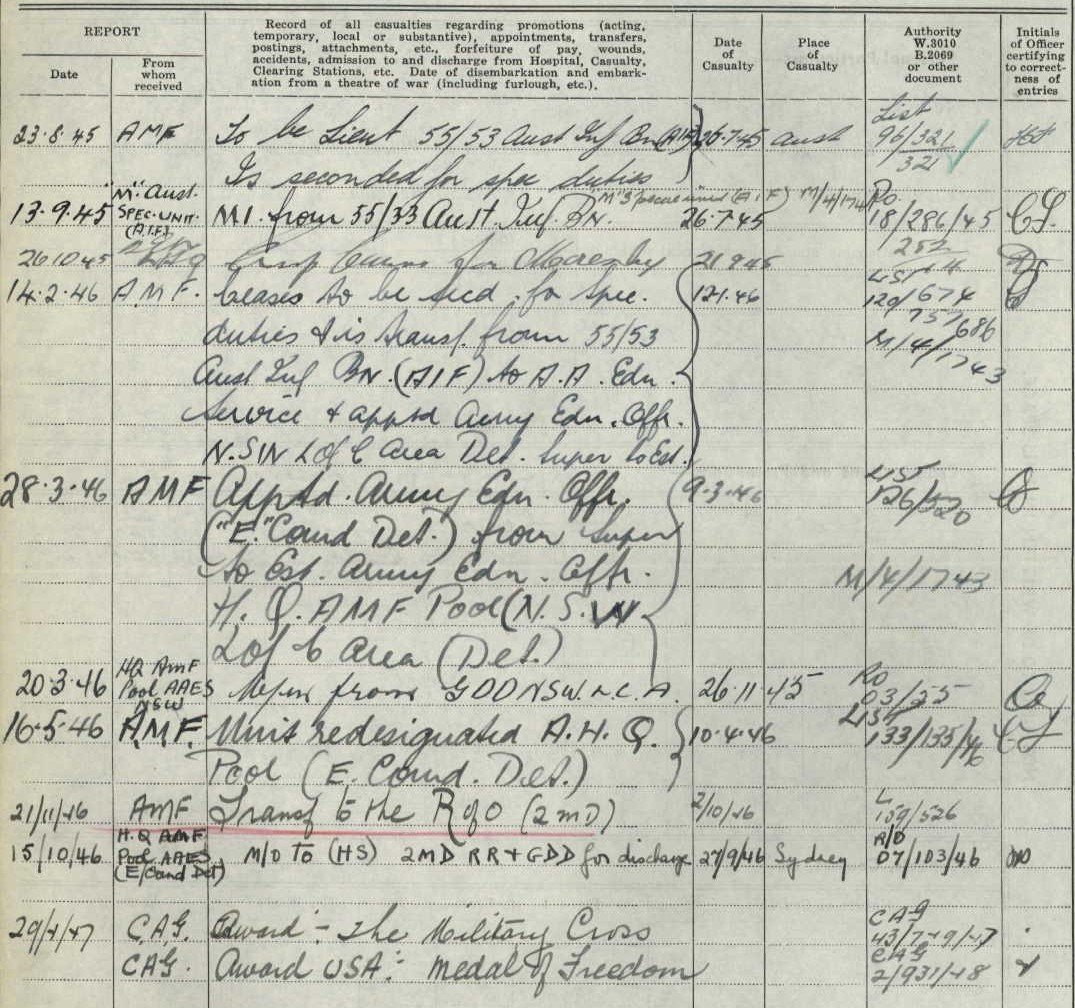

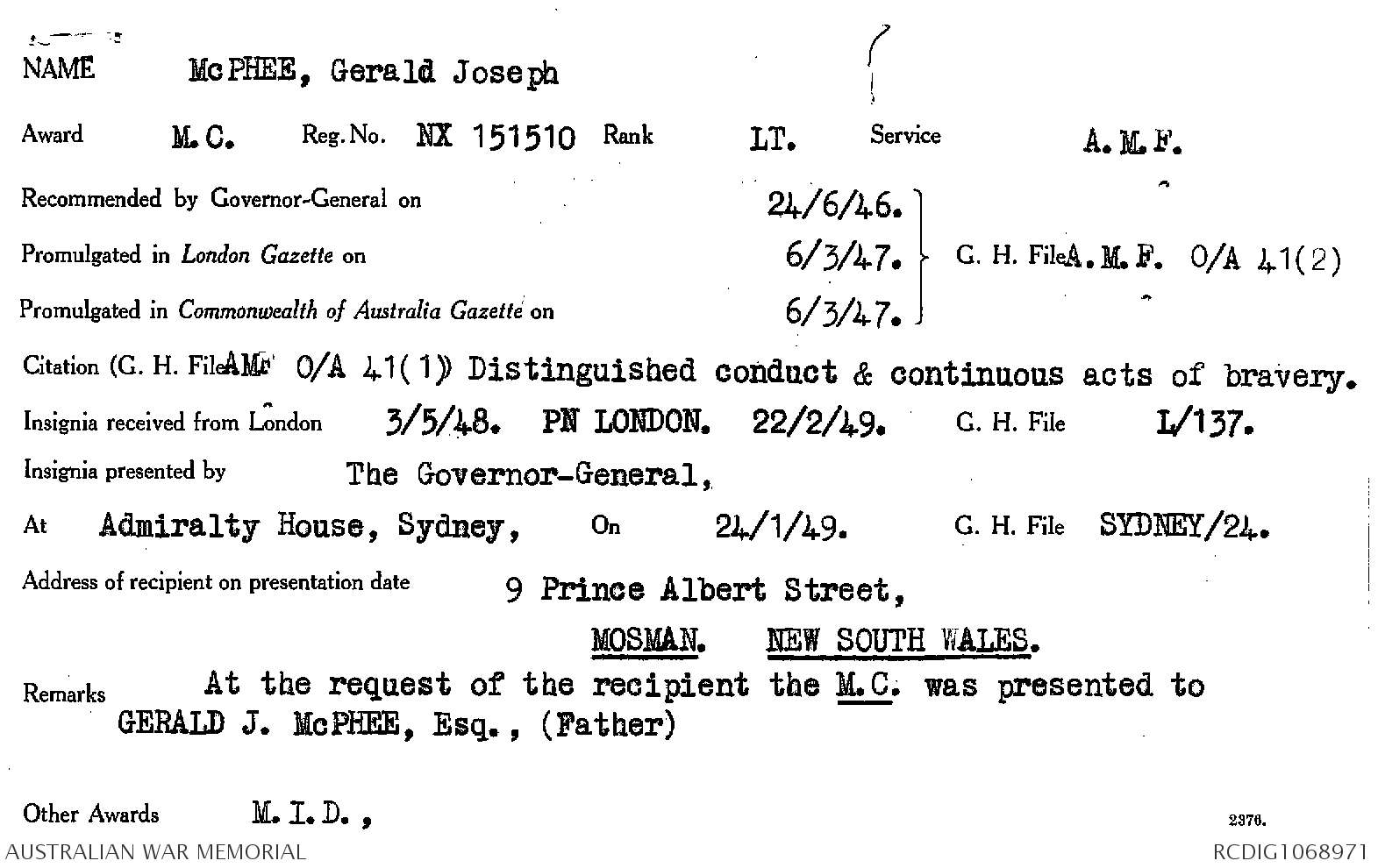

What can be determined from his records is he was awarded honours from both the Australian and United States armies, along with Mentions In Despatches. His official war record notes:

Lieutenant Gerald Joseph McPhee

Service number NX151510 – Military Cross

Ranks Held Lieutenant, Sergeant

Final Rank Lieutenant

Service Australian Army

Unit M Special Unit

Conflict/Operation Second World War, 1939-1945

Gazettes Published in Commonwealth Gazette in 1947-03-06

Published in London Gazette in 1945-07-19

Published in London Gazette in 1947-03-06

Published in Commonwealth Gazette in 1945-07-19

Published in Commonwealth Gazette in 1948-01-02

The Australian ones were:

MID - Military Cross Recommendation - September 12th, 1945

Citation: 'For distinguished conduct, continuous acts of bravery, and devotion to duty in the field, whilst engaged on protracted special intel’ defence operations of a dangerous nature in enemy occupied territory.'

Details:

From 29th March to July 1945, Lieut. (then Sergeant) McPHEE rendered excellent service with an A.I.B. party in Northern Bougainville. With commendable coolness, courage and reliability, he carried out advanced patrol work on his own, and provided, by W/T, continuous valuable intelligence of enemy movements and dispositions, during a period when determined enemy patrols were seeking to destroy the party.

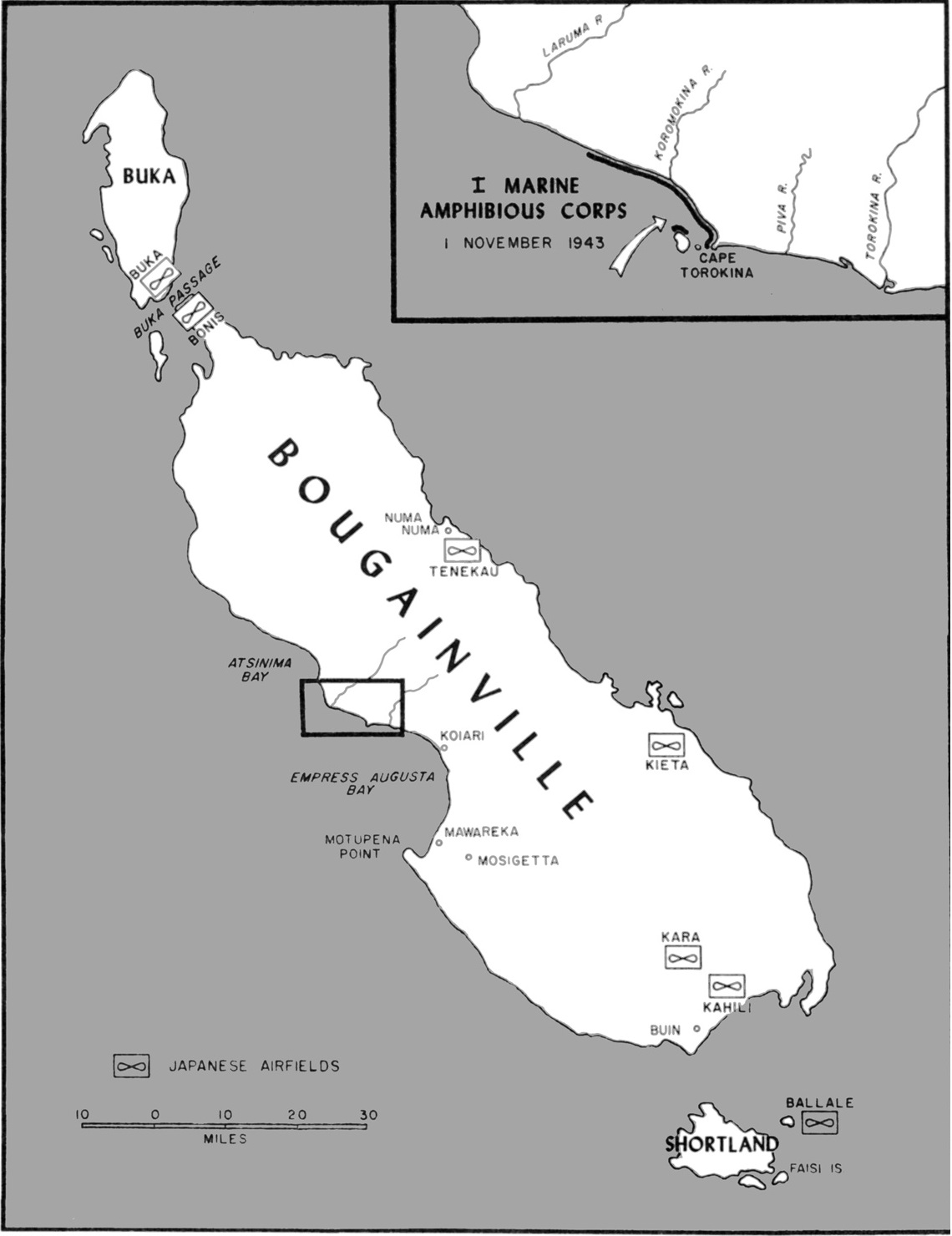

He was directly responsible for the safe evacuation of most of the Coast-Watching organisation from Bougainville in July 1943.

From October 1943 to March 1944, Lieut. (then Sergeant) McPHEE carried out further meritorious intelligence patrols in connection with an A.I.B. patrol led by Lieut. KEENAN RANVR (DSC-Legion of Merit).

Prior to the U.S. landing at Torokina, he assisted in patrols of this area and later operated as guide and scout with US and Fijian patrols. During the whole period he gave courageous service of high standard and efficiency as radio operator.

From November 1944, Lieut. McPHEE has been on active service in North Bougainville with Lieut. Bridge, RANVR (DSC-Legion of Merit) maintaining efficient radio communication. He displayed cheerfulness, courage, bushcraft, and devotion to duty in dangerous and trying conditions in contact with the enemy in front of Allied positions. Lieut. Mc Phee personally organised several successful patrols, killing and capturing a number of the enemy.

He was also awarded the US Freedom Medal:

Australian Military Forces-Medal of Freedom … Lieut. Gerald Joseph McPhee NX151510. … U.S. AWARDS ANNOUNCED (1947, December 19). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 5. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article18054288

AMERICAN WAR DECORATION

Medal Of Freedom For 15 Australians

CANBERRA, Dec. 18.- Fifteen Australians, including Lieut. Generals Sir Leslie Morshead and F. H. Berryman. are to receive the Medal of Freedom, an American war decoration conferred on non-Americans "in recognition of gallantry, heroism or meritorious achievement in connection with military operations which aided the United States in the prosecution of the war against Japan in the South-West Pacific Area."

The medal is the equivalent of the Legion of Merit bestowed on Americans. The Acting-Prime Minister (Dr. Evatt) in announcing the awards, said that they had been authorised by the Commander-in-Chief U.S. Far East Command (General MacArthur) as the first instalment of 102 U.S. awards for Australians accepted by the Commonwealth Government.

Arrangements for presentation of the awards by the American authorities would be decided later. Dr. Evatt said that the Government had conveyed its appreciation of the tribute to the United States Government.

The recipients are:

ARMY.

Medal of Freedom with silver palm: Lieut.-General Frank Horton Berryman, C.B., C.B.E., D.S.O. (now G.O.C. Eastern Command, N.S.W.; commanded the 2nd Australian Corps, served in the Middle East, Java and New Guinea); Lieut. General Sir Leslie Morshead, K.C.B., K.B.E.,- C.M.G., D.S.O., E.D. (G.O.C. 2nd Australian Army; G.O.C. A.LF., Middle East, commanded the 9th Division at the siege of Tobruk, and temporarily commanded New Guinea Force); Brig. Victor Clarence Secombe, C.B.E. (served in both World Wars, was C.O. Headquarters Engineers, A.LF. Division).

Medal of Freedom with bronze palm: Major John Cyril Davies Litchfield.

Medal of Freedom: Major Basil Fairfax Ross; Capt. Herbert Albinus Jackson Fryer, M.B.E.; Capt. Alistair Howell MacLean; Lieut. Gerald Joseph McPhee; Capt. Thomas Daniells Merton; Lieut. Murray Barnett Tindale.

NAVY.

Medal of Freedom with bronze palm: Commander Robert Bagster Atlee Hunt, O.B.E., R.A.N.; Lieut. Montague William Mathers, R.A.N.R. (S), now Lieut.-Commander, R.A.N.V.R.

Medal Medal of Freedom: Sub. Lieut. Albert Molkin Andresen, R.A.N.V.R.

R.A.A.F.

Medal of Freedom with bronze palm: Squadron-Leader Bertram Francis Norman Israel.

Medal of Freedom: Squadron-Leader Ronald Albert Robinson, M.B.E. The names of recipients of the remaining 87 awards will be announced when the United States authorities in Washington have approved the awards. AMERICAN WAR DECORATION (1947, December 19). The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 - 1954), p. 22. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article46825401

Gerald McPhee was involved in the Bougainville campaign. The Bougainville campaign was of the largest campaigns fought by Australians during WWII and also one of the final campaigns of the war in the Pacific. Waged largely by militia formations, it wrapped up a series of actions and campaigns waged against the Japanese by Australian, American, Fijian and New Zealand forces, beginning at the time of the Japanese invasion of Bougainville and the adjacent Buka Island in early 1942.

Bougainville and Buka are the two northern islands of the Solomon Islands group. Before World War II they were held by Australia under a League of Nations mandate. The island was named after the French navigator Louis Antoine de Bougainville in 1767.

Bougainville is the largest island of the Solomon Islands chain, about 130 miles (210 km) long and 30 miles (50 km) wide, with an area of about 3800 square miles (9800 km2). Located near the north-western end of the chain, 190 miles (300 km) east of Rabaul, it is a mountainous island, dominated by the Emperor and Crown Prince ranges, with two active volcanoes. The tallest of these (Mount Balbi) reaches to 10,171 feet (3100 meters) in height.

The lower slopes and coastal plains are covered in dense jungle. With an average annual rainfall of around 100 inches (250 cm) the island is wet year-round. It is extremely humid throughout the year, with a mean temperature of 27 °C (80 °F). Although seasons are not pronounced, June through August is the cooler period, and north-westerly winds from November until April bring more frequent rainfall, and occasional squalls or cyclones.. Malaria and other tropical diseases are prevalent. The island is home to some of the greatest biodiversity in the region both above and below the waters with spectacular reefs and lagoons.

Kokopau is the arrival point on the main island after crossing from Buka. For virtually all visitors, this is the starting point on Bougainville for a journey southwards through some very picturesque coastal village communities, which include Tinputz at the most north-easterly point of the island.

In late 1941, there was a good anchorage with a small landing for loading copra at Buin, near the southern end of the island, and a grass airstrip. A 1400' (430m) airstrip had been completed on Buka Island at Buka Passage, the narrow strip of water between Buka and Bougainville, which was also the British administrative centre. There were several native trails, mostly along the coast, but only the trail around the northwest coast of the island was usable by motor vehicles.

The population was about 54,000 islanders who spoke around 18 different languages, and only 100 Europeans and 100 Asians (mostly Chinese). Today there are several indigenous languages in Bougainville. These include both Melanesian and Papuan languages, none of which are spoken by more than 20% of the population. The larger languages such as Nasioi, Korokoro Motuna, Telei, and Halia are split into dialects that are not always mutually understandable. For most Bougainvilleans, Tok Pisin is the lingua franca, and at least in the coastal areas Pisin is often learned by children in a bilingual environment.

European women and children were ordered to evacuate on December 12th 1941, and the remaining Europeans were ordered to evacuate on December 18th. However, many of the European residents refused evacuation, including a sizable fraction of the missionaries on the island. Among those who remained were Jack Read and Paul Mason, who became part of the "Ferdinand" Coast Watcher organisation under Commander Eric Feldt, RAN. Feldt chose the name Ferdinand, from the popular children's classic, The Story of Ferdinand, penned by Munro Leaf and illustrated by Robert Lawson, and first published in 1936.

I chose Ferdinand … who did not fight but sat under a tree and just smelled the flowers. It was meant as a reminder to Coastwatchers that it was not their duty to fight and so draw attention to themselves, but to sit circumspectly and unobtrusively, gathering information. Of course, like their titular prototype, they could fight if they were stung. - [Eric Feldt, The Coastwatchers, Melbourne, 1946, p.95]

Read and Mason transmitted vital early warnings of Japanese air raids against Henderson Field during the Guadalcanal campaign.

On January 29th 1942, Japanese Imperial Headquarters had ordered Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto to plan for the occupation of Lae and Salamaua in New Guinea, with follow-up operations against Port Moresby and Tulagi in the Solomons. This meant the Japanese had plans to invade Bougainville and Buka in order to secure an anchorage to support operations further east in the Solomons. Five weeks after the order had been issued, naval forces set out from Rabaul to seize Lae and Salamaua to the south and Queen Carola Harbour on Buka Island to the east. Two cruisers and six destroyers sailed for Queen Carola Harbour in north Buka.

Lance-Corporal Jack Matthews was one of a party at Kessa, overlooking the harbour:

At 0900 hours on 9 March 1942, we noticed a number of ships on the horizon, which appeared to be approaching. This proved to be so, and later we could identify them as Japanese naval vessels ... Sig Sly immediately tried to contact [naval coastwatcher] WJ Read on the radio for half an hour but with no success. During this time the ships were getting very close, so I decided to dismantle and hide the radio in case they should land in our vicinity.

The Australians continued observing the warships. Eventually they got a message to Read, who was able to inform authorities at Port Moresby. Tragically, a press release back in Melbourne noted that Japanese ships had visited Kessa, so the Japanese knew to return in search of Coast Watchers. Consequently a planter, Percy Goode, was killed and a missionary was taken prisoner.

Some records state the natives on Bougainville were more cooperative with the Japanese than in other parts of the Solomons, citing a number of reasons for this. The evacuation of the European population was incredibly disturbing to the native population, who rioted at Kieta on January 23rd 1942 and were brought under control only by the efforts of one of the German residents who had refused evacuation. The influence of German missionaries and the fact that the Japanese had so easily driven out the Allies also had their effect on the attitude of the natives.

Those who served in this area state that without the islanders they could not have survived, let alone successfully carry out their missions, without the help of the residents.

By the end of April 1942, having consolidated their positions in New Guinea, the Japanese were ready to step up operations and launch 'Operation Mo', the occupation of Port Moresby and Tulagi. The intention was to establish air bases in southern New Guinea to facilitate air operations against northern Australia, take Nauru and Ocean Islands with their phosphate deposits, and capture the Solomons to cut across the most direct Australia – United States shipping routes.

Tulagi was occupied without opposition on May 3rd. The Battle of the Coral Sea stopped the Port Moresby invasion force, while the Battle of Midway, north-west of Hawaii, was a further setback to Japanese forces as they lost the aircraft carriers needed to support their operations in the Solomons. Three months later, the American 1st Marine Division landed at Tulagi and Guadalcanal Islands, starting the battle to reclaim the Solomons.

Buka and Bougainville had been overrun by the end of April. The Australian Coast Watchers and the troops of the 1st Independent Company remained to observe Japanese land, sea and air activities. They were able to give warning of enemy shipping movements and impending attacks on the American forces at Tulagi and Guadalcanal. The observation posts of Lieutenant John Read in northern Bougainville and Lieutenant Paul Mason in southern Bougainville were especially important to the Americans because they were very well placed to give warnings.

Lieut. Read was in the best position to warn of impending enemy air attacks on Guadalcanal and Tulagi, giving two hours advance notice. The importance of this was noted by an historian of the coastwatching operations:

This lengthy warning enabled the various Allied commands to prepare accordingly. Shipping could be dispersed from highly vulnerable concentrated areas to widely scattered positions of maximum safety. And fighter aircraft had time to be fuelled, armed, and dispatched to high altitudes—ready to pounce on the attacking force. In addition, naval warships were able to form a defensive antiaircraft perimeter around the beachhead. The element of surprise—the best weapon in any assault—was taken away from the Japanese. That meant that coast watching alone was responsible for the success of the air war.

Paul Edward Mason, overlooking Buin in south Bougainville, was in an excellent position to report ship movements. Extracts from Jane's Fighting Ships were air-dropped to him, enabling Mason to send very accurate identifications. Messages were kept short and simple. For example, on August 7th 1942, after spotting enemy aircraft heading for Guadalcanal, Mason signalled:

From STO. Twenty-four torpedo-bombers headed yours.

The code-name STO used the initials of Mason's married sister. With this warning, all but one of the Japanese aircraft were shot down and no American or Australian ships were damaged. On another occasion, Mason reported at least sixty-one Japanese ships heading for Guadalcanal. So vital was their contribution that Admiral William 'Bull' Halsey, United States Navy commander of the forces retaking the Solomons, declared: 'The Coastwatchers saved Guadalcanal and Guadalcanal saved the Pacific'.

By February 1943, the American forces were in control of Guadalcanal. Many of the 13000 Japanese troops withdrawn from the Guadalcanal area ended up on Bougainville and Buka Islands. This would rise to over 60,000.

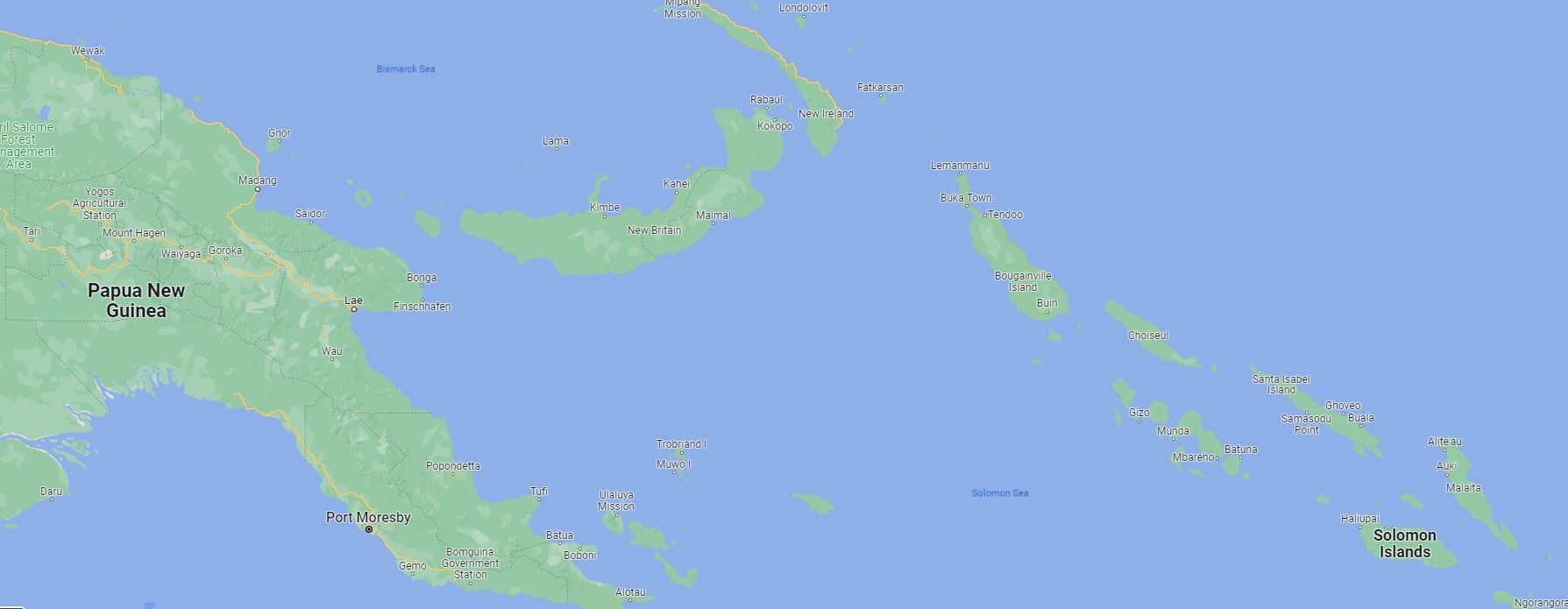

PNG, Bougainville, New Britain and the Solomons. Map: Google

In May 1943, a plan to cover the whole of Bougainville with Coast Watchers was implemented. This included:

Keenan - north of Porapora

Read and Robinson - Central east

Sgt. McPhee - West coast

Paul Edward Mason and Stevenson - South end

Mason and Stevenson's party included:-

- 8 soldiers

- Usaia

- William McNicol

- 10 native police

On Saturday 26 June 1943, Stevenson's party was attacked by a Japanese patrol. Stevenson was killed with the first shot. The rest of the party fought back killing five Japanese. They retreated with their weapons only. They came across one of the natives who had led the Japanese to their camp, and immediately executed him. They caught up with Mason's party the next day with the Japanese still on their trail. They were short on supplies and supply drops were again out of the question.

At this time a decision was made to evacuate all Coast Watchers off Bougainville, due to the recent relentless Japanese activity to locate them. Mason was ordered to join McPhee on the north west coast. They had to follow the west coast as the east coast was swarming with Japanese.

In June and July, the Americans had landed in the New Georgia island group and captured four airfields, all in Allied fighter range of Bougainville. [8.]

Some details of those incidents, actions and forays which Gerald McPhee was a part of can be glimpsed through the records made by others:

July 1943:

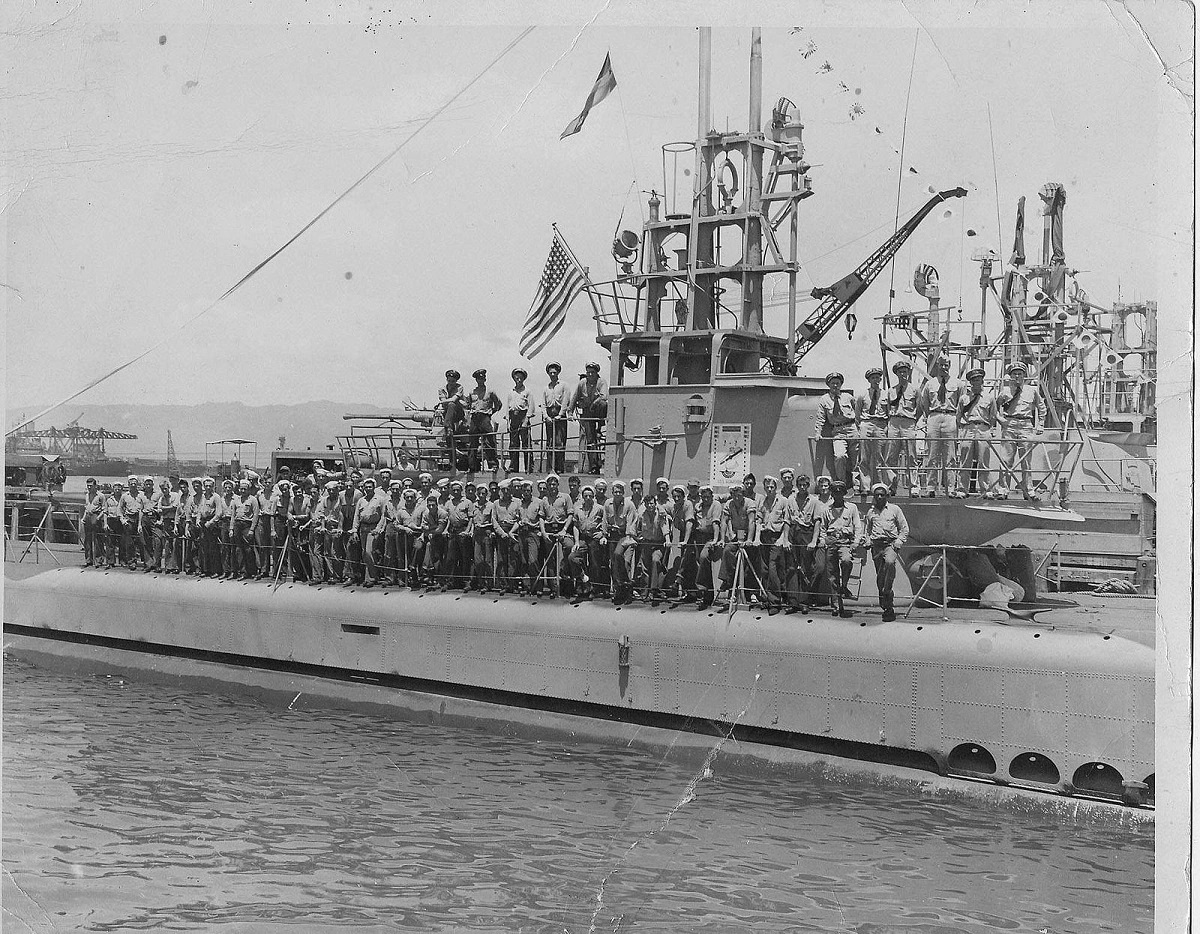

US Navy Submarine USS Guardfish (SS-217) operated out of the Brisbane Submarine Base during WW2. USS Guardfish left Pearl Harbor on January 2nd 1943 to patrol off the Truk area. She sank a Japanese patrol vessel, a 1,300 ton cargo ship and the Japanese destroyer Hakaze on January 23rd 1943. She moved south and attacked a large convoy near Simpson Harbor, Rabaul. The Japanese defences were so fierce that USS Guardfish was forced to leave the area. USS Guardfish arrived at Capricorn Wharf in Brisbane on February 15th 1943 ending her 3rd war patrol.

USS Guardfish left Brisbane on March 9th 1943 for her 4th War Patrol in the Bismarck Sea, Solomon Islands and New Guinea area. She returned to Brisbane on April 30th 1943, after a very quiet patrol with no recoded kills.

USS Guardfish's 5th War Patrol found her returning to the same area. She left Brisbane on May 2nd 1943. She sank the 201 ton Japanese freighter, Suzuya Maru and damaged another freighter. USS Guardfish together with US Navy Subchaser SC 761, was instrumental in rescuing a large number of Australian and New Zealand Coast Watchers from Bougainville in July 1943. She returned to Capricorn Wharf in Brisbane on August 2nd 1943 for a long needed refit. [3.]

Extract from the book, Save Our Souls: Rescues Made by U.S. Submarines During World War II By Douglas E. Campbell:

USS Guardfish went to Tulagi to prepare for and execute special tasks. She arrived at Tulagi on July 14th 1943 and underway a week later, with air cover, for her special mission.

Under cover of darkness, on 24 July, GUARDFISH surfaced at Atsinima Bay on Bougainville Island and evacuated a total of 62 personnel - 22 Australian commandos, two remaining survivors from a downed Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) PBY Catalina (SGT Frederick Gordon Thompson and Corporal Ronald Alexander Wettenhall), seven Chinese nationals who had been hiding in the hills, one Fijian, 9 native police officers with their 15 scouts and two native wives with a child each, and two coast watchers — John Robert Keenan and LT Paul Edward Allen Mason.

The 22 Australian commandos evacuated from Bougainville were:

Staff Sergeant Bertram Louis Cohen (VX117350, M Special Unit)

Sergeant John Methven Collier (SX1013, 2/48th Infantry Battalion)

Sergeant Harold Joseph Broadfoot (QX38133, M Special Unit)

Acting Sergeant Vivian Morris Day (VX74803, was stationed at the Australian Jungle Training Centre when discharged from the Army)

Acting Sergeant Gerald Joseph McPhee (NX151510, M Special Unit)

Acting Sergeant Walter Allan Percy Radimey (NX44839, 1 Independent Company)

Acting Sergeant Alan Stratford Hatherly (NX110237, 1 New Guinea Infantry Battalion)

Acting Sergeant Kenneth Harry Thorpe (QX28945, 1 New Guinea Infantry Battalion)

Acting Sergeant Frederick James Furner (NX394418, unknown station)

Acting Corporal Noel Lancelot McLeod (NX49729, Z Special Unit)

Acting Corporal Alan Russell Little (NX18815, HQ 1 Australian AA Bde Sigs)

Signaller Alan Maitland Falls (NX84318, stationed at District Accounts Office, New South Wales, Australia when discharged)

Signaller Ronald Joseph Cream (WX13199, Z Special Unit)

Signaller Gordon Rex Kotz (SX11395, 2/3 Field Regiment)

Signaller Ernest John Parker Rust (NX127852, Z Special Unit)

Signaller Albert Edward Eastlake (VX89256, M Special Unit)

Sapper Bernard Michael Bastick (NX86844, M Special Unit)

Sapper George Maxwell McKenzie (NX139989, was with the 1st Australian M T Workshops, Australian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers (AEME), upon discharge)

Sapper Stanley Gage (NX110501, was with the 14th Australian Wks & Pk Squadron, British Commonwealth Occupation Force (BCOF), upon discharge)

Sapper Denzil Kenneth Ayliffe (NX92192, M Special Unit)

Private Stanley Stonehouse (V X146945, was with the 24th Infantry Battalion upon discharge)

Private H. Woods

The others evacuated on this date were:

9 Native Police Officers:

Lance Corporal Tamuga

Lance Corporal Kugi

Constable Porom

Constable Hosem

Constable Uni

Constable Pompey

Constable Sobon

Constable Lunga

Constable Yalum

19 Other Natives:

Dai-yau (female) with child Taria

Yema (female) with child Napoli

Ponio, Sakio, Seilo, Unkam, Kasin, Noki, Gabriel, Wiski, Sikiovi, Pemigi, Oua, Wongusausa, Yeramini, Orara and Pipiranu

8 Asians:

Chin Yung, Hee You, Chan Cheung, Wong Tu, See To Chun, Fee Chow, Foe Kiang and Eroni Kotosuma. Chin Yung’s wife and their 6 children had been evacuated by GATO on March 29th 1943. Hee You’s wife and their 3 children had also been evacuated by GATO on March 29th as had Wong Tu’s wife and daughter.

With them safely aboard, she put out to sea to transfer the evacuees to an American sub-chaser, SC-761. SC 761 left USS Guardfish at 0540 hrs and headed for Guadalcanal. The 59 passengers were very hungry and tired. The Commander of SC 761, Lt. Ronald B. Balcom, USNR, asked "Frenchie" their cook, to feed their hungry guests. The ship was overstocked with Salmon which they were always required to draw from stores at their Naval supply facility. The crew of SC 761 were sick of Salmon, so "Frenchie" took this opportunity to reduce their stocks. John Keenan offered some of his Chinese to assist in the galley. Using hand signals "Frenchie" to communicate with the Chinese, they served up several cases of Salmon and large helpings of rice. After this hearty meal, the Chinese meticulously cleaned the galley, and all the plates and cooking and eating utensils. They even cleaned the aft crew quarters where many of them had eaten. "Frenchie" would loved to have kept a few of these Chinese in his galley for the rest of the war.

Lt. Comdr. John R. Keenan consumed a pot of hot tea while he relived some of his experiences on Bougainville. The Japanese would constantly track them while they were broadcasting with their teleradios, so they were constantly on the move to avoid capture. The Coast Watchers had their photograph taken on the forecastle of SC 761 after they had showered, shaved and eaten. Lt. Cmdr. Keenan advised that he had lost two men who were captured by the Japanese and thereupon beheaded. [3.]

The Coast Watchers on the forecastle of SC 761 after they had showered, shaved and eaten.

USS Guardfish. Official U.S. Navy Photograph

Four nights later, the submarine returned to the same location and evacuated another 23 - two more coast watchers (LT William John “Jack” Read, AIF, and Captain Eric D. “Wobbie” Robinson, AIF), a Fijian Methodist missionary (Usaia Sotutu) and 11 scouts (Anthony Jossten, Sergeant Yauwika, Corporal Sali, and Constables Sanei, Ena, Gwanda, Naia, Iamulu, Bero, Kiniwai and Numbundameri), and a mix of nine loyal natives and Chinese refugees (Tamti, Tomaira, Keri, Womaru, Wili, Mabianga, Sarawa, and Giwa with her child Ema).

In total, GUARDFISH evacuated 85 people for transport away from Japanese domination and possible incarceration or execution.

Caption: Australian Coast Watchers on Bougainville, November 29, 1943, after they had been picked up from New Ireland by PT boats. Several New Ireland native assistants are with them. The men carry British SMLE rifles and U.S. M-1 carbines. Photographed by Sarno. Note sign at top: "This Beach is reserved for PT Base Boats" . This again looks like Captain Rolf Charles Cambridge, AIF, 'M' Special Unit and 'Z' Special Unit, second from left and Gerald McPhee, last at right, front row. Item USMC 69275, Official U.S. Navy Photograph

December 1944:

Neither were supply drops without risk for the aircrews. In his report from central Bougainville, Flight Lieutenant N C Sandford, 2 DK patrol, described a supply drop that went badly wrong on December 19th 1944.

On 19 December, Lieut. Bridge was asked to prepare to receive a drop on the following day. A RNZAF (Royal New Zealand Air Force) Venture circled the area at 9.5am. The first run was made from the main range over the dropsite towards the sea but no cargo was released. The pilot then came in from the lower end of the valley and made his run towards the mountains. The aircraft made a good approach with wheels down and bomb bay doors open but cargo did not start to drop until the aircraft was over 400 yards (365 metres) past the dropsite. The cargo continued to fall in separate bundles for some time and no attempt seemed to be made to retract the wheels despite the fact that the aircraft was heading towards the main range at low altitude. The aircraft rose at the last moment and appeared to clear the range but suddenly the starboard wing rose sharply and the aircraft disappeared from sight. Shortly afterwards I heard the crash and almost immediately a dense black column of smoke appeared. I immediately took a bearing on the smoke then called to Lieutenant Bridge, who had remained in the camp area and so had not witnessed the crash that the aircraft had crashed some 3 or 4 miles (approximately 5-6 km) away on bearing 26oM. 2WA was advised and PB's were instructed to proceed with all speed possible to the scene of the crash. A second party under Sergeant McPhee was formed to take food and medicines to and bring out any survivors.

At 11.20 hours a note was received from the latter party advising that two of the airmen – Hobbs and Murphy – had been killed and that the others – Scarlett, Nuttal and Gardiner – were badly injured. 2WA was advised and a Doctor and drugs were requested. The rescue party arrived back at Aita at 18.00 hours with Nuttal, Gardiner and the body of Scarlett who had died as a result of extensive 3rd degree burns. Nuttal was the more seriously injured of the two survivors and, despite all we could do he died from shock consequent to extensive burns at 22.30 hours.

Gardiner, suffering from a fractured femur, burns and shock became delirious at 23.30 but responded to treatment and by morning I was able to pronounce him out of danger. On 21st December 1944 in response to a suggestion from DSIO Nor Sols Lieut. Bridge gave order that a small strip would be cleared and local natives were recruited to prepare the site selected. A burial party was sent to the scene of the crash to bury Hobbs and Murphy and salvage what confidential documents might be in the aircraft and ensure that the I.F.F. equipment was destroyed.

Scarlett and Nuttal were buried at Kushi village under a grove of breadfruit trees. On my return to the area in January 1945 I had two hardwood crosses suitably inscribed and erected over their graves. - [NAA Item 37A B3476, 'Report by Lieutenant N.C Sandford, 2 DK Patrol, Central Sector, Bougainville Island, 12.1.44 – 18.6.45]

Sandford's report continues that attempts to construct an airstrip and problems with aircraft led to Gardiner, now the only crash survivor, being evacuated on foot. On December 28th a stretcher party carried him overland from Aita to Kurnaio Mission where a barge transported the patient to Torokina. The party arrived there on January 1st 1945 and Sergeant Gardiner was flown to New Zealand the following day. From: - DVA (Department of Veterans' Affairs) (2019), Supply drops, DVA Anzac Portal, https://anzacportal.dva.gov.au/wars-and-missions/world-war-ii-1939-1945/resources/coastwatchers-1941-1945/supply-drops

Saratoga (CV-3) aircraft attack Japanese airfields on either side of the Buka passage, 1–2 November 1943. Buka Island is on the right, with bombs bursting on its airfield. Bonis is at left. View looks to the southwest (80-G-89080). USMC photo

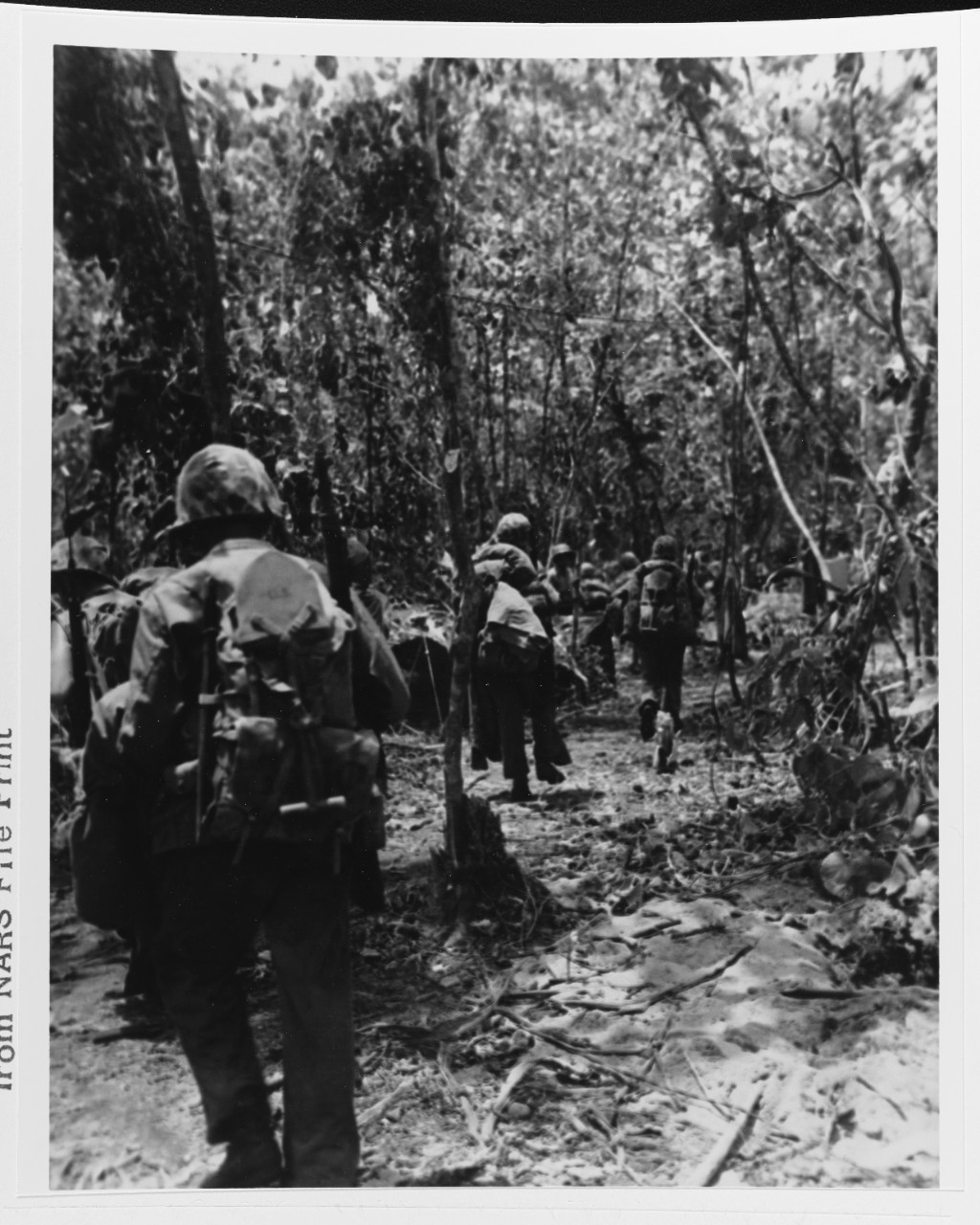

Marine raiders marching back from the point of Empress Augusta Bay, near Cape Torokina, Bougainville, after fighting for 27 straight hours, circa 1–9 November 1943 (80-G-56408). US Marine Corps photo

Marines kneel in prayer for their fallen buddies at Christmas Eve memorial services in a Bougainville cemetery, 24 December 1943. In the background, other Marines search the grave markers for the names of lost friends (80-G-211304). USMC photo

When the Australians joined in the battle for Bougainville in late 1944, relieving the American garrison at Torokina, on Bougainville’s west coast, Lieutenant General Stanley Savige’s II Australian Corps (the 3rd Division, and the 11th and 23rd Brigades) were sent into three areas radiating from Torokina: the Central, Northern and Southern Sectors. In the Central Sector, the Australians followed the Numa Numa trail across the island’s mountainous spine to the east coast. In the Northern Sector, the Australians followed the north-west coast towards Buka. The advance went well until a small force made a disastrous amphibious landing at Porton Plantation in June 1945. The main fight, however, was in the Southern Sector, where the 3rd Division (the 7th, 15th and 29th Brigades) advanced towards Buin, the major Japanese base on the island. [9.]

Patrolling was slow work due to the terrain and the danger; the maximum rate of advance was six minutes to cover 100 yards (about 90 metres). Patrolling was physically and mentally exhausting. Contacts with the enemy were frequently very close, only metres apart. Pre-existing tracks and clearings were considered “death traps” as the Japanese often prepared pillboxes with firing lanes for their machine-guns, and locations were pre-ranged for their artillery. They would set up ambushes to cover approaches to log crossings over creeks and other natural obstacles. The Australians advocated “scrub bashing” where possible, moving through the jungle rather than along tracks. “Leading and second scouts are suicide jobs,” a 24th Battalion report noted.

Occupying and developing new defensive positions was accompanied by a frenzy of digging, cutting, and carrying. On taking a new position, soldiers and Bougainvilleans immediately began to dig weapon pits and sleeping bays, and to lay wire entanglements along the perimeter. Offices for the battalion headquarters, the signals office and equipment, as well as for stores and ammunition, were also dug underground. Tents erected within the perimeter were kept low to blend with the scrub. Signallers laid signal lines into the battalion headquarters and to each company. Reconnaissance patrols were sent out to the front and flanks, and forward listening posts were established.

The conditions were physically exhausting. In the damp jungle environment the men were always wet from rain, river and creek crossings, muddy tracks and perspiration. Uniforms would rot and boots would disintegrate. Equipment and stores become mouldy. Much had been done to combat malaria and other tropical diseases, but skin irritations and infections still occurred.

Officers and non-commissioned officers (NCOs) had to be mindful of their soldiers’ health and welfare. As there were so few men, responsibility for leading and conducting patrols fell upon the same junior officers, NCOs and soldiers time and again. There was no relief from stress and strain. Earlier in the campaign, morale almost collapsed in two battalions from the 7th Brigade, with soldiers refusing to patrol and men having mental breakdowns. These incidents were partly attributed to physical and mental exhaustion. New administrative policies were introduced to provide some respite to the front line, such as establishing rest areas closer to the front. Other techniques included enforcing discipline and hygiene, and ensuring soldiers received mail, tobacco, a warm meal, and water for bathing and washing clothes. Religious services and sport also contributed to maintaining morale. Corporal Davis thought the campaign “nerve wrecking” but “being busy kept us from our fears.” He also found solace in his religious faith. Private Lyne recalled instances of a few soldiers shooting themselves in the foot or hand “to get out of it”. Specific figures for what would be described as “psychiatric casualties” suffered by Australian forces on Bougainville were not systematically recorded. The 24th Battalion’s adjutant noted frankly:

It is not possible to weed out neurotic personnel and those who are NOT suited for operations on account of either temperament or just plain fear. A very small sprinkling of these can quickly spread the disease and it should be watched very closely and stamped out immediately. [9.]

The Australian Corps controlled about two-thirds of Bougainville when the war came to an end. Fifteen Australian infantry battalions served on Bougainville along with elements of the Papuan and the 1st New Guinea Infantry Battalions.

From Bougainville’s pre-1942 population of 54,000 people, it is estimated that up to a quarter died during or because of the conflict. That's 13 thousand souls - a devastating number that impacted on every single family.

More than 30,000 Australians served on the island, 516 Australians died and 1,572 had been wounded. Between 1943 and 1945, more than 300 New Zealanders also lost their lives supporting the US and Australian campaigns.

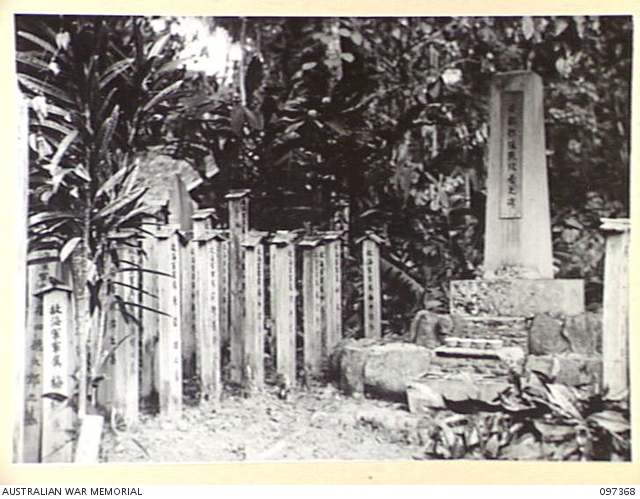

The Australian War Memorial states about 65,000 Japanese occupied the island when the Americans arrived in 1943; at surrender, there were just over 23,800. The Australians had killed 8,789 Japanese during the nine-month campaign, and the Americans estimated they had killed about 9,890. Thousands more Japanese soldiers died from sickness, disease and starvation.

A Japanese memorial to the dead located near the former Japanese naval headquarters at Buin on the island of Bougainville, September 28th, 1945. A memorial stone (right) is surrounded by wooden grave markers commemorating the names of individual soldiers and sailors. Four bowls on the shrine contain food and water. It is unlikely that any remains or ashes were actually buried here as the Japanese, who traditionally cremated their dead, usually sent the ashes of the fallen back to their families in Japan or stored them until such time as it was possible to do so. Image courtesy Australian War Memorial.

Those Australians who died in the fighting in Papua and Bougainville are buried in the Port Moresby (Bomana) War Cemetery, their graves brought in by the Australian Army Graves Service from burial grounds in the areas where the fighting had taken place.

The unidentified soldiers of the United Kingdom forces were all from the Royal Artillery, captured by the Japanese at the fall of Singapore; they died in captivity and were buried on the island of Bailale in the Solomons. These men were later re-buried in a temporary war cemetery at Torokina on Bougainville Island before being transferred to their permanent resting place at Port Moresby.

The cemetery contains 3,824 Commonwealth burials of the Second World War, 699 of them unidentified. Over 600 Indian soldiers who fought in the Second World War are buried at the cemetery. There is also 1 Non war and 1 Dutch Foreign National burials here.

The Port Moresby Memorial stands behind the cemetery and commemorates almost 750 men of the Australian Army (including Papua and New Guinea local forces), the Australian Merchant Navy and the Royal Australian Air Force who lost their lives in the operations in Papua and who have no known graves. Men of the Royal Australian Navy who died in the south-west Pacific region, and have no known grave but the sea, are commemorated on the Plymouth Naval Memorial in England, along with many of their comrades of the Royal Navy and of other Commonwealth Naval Forces. Bougainville casualties who have no known graves are commemorated on a memorial at Suva, Fiji.

At least 321 allied airmen and 280 US sailors were rescued by Coast Watchers behind enemy lines during the Solomon Islands Campaign (Feldt The Coastwatchers, p.153), and there were many others saved and evacuated from New Britain. Other statistics collated show Coast Watchers rescued 75 POW's, 190 Missionaries, 260 Chinese people and countless Papua New Guineans and Island peoples - they left no one behind; if there was room on the deck of a ship or submarine, they loaded them up and got them the hell out of there.

Perhaps the most famous of those rescued by the Coast Watchers was US Navy Lieutenant John F. Kennedy, who later became 35th President of the United States. After his patrol torpedo boat was sunk in the Solomons, and Kennedy and his crew reached Kolombangara Island, they were found by Coastwatcher Sub-Lieutenant Arthur 'Reg' Evans who arranged their rescue. Biuku Gasa (27 July 1923 – 23 November 2005) and Eroni Kumana (c. 1918 – 2 August 2014) were Solomon Islanders of Melanesian descent, who were sent out by Evans and found John F. Kennedy and his surviving PT-109 crew following the boat's collision with the Japanese destroyer Amagiri near Plum Pudding Island on August 1st 1943. They were from the Western Province of the Solomon Islands. President Kennedy later welcomed Evans as his guest at the White House.

Image: President John F. Kennedy visits with A.R. "Reg" Evans (left), an Australian Coast Watcher from New South Wales who, while stationed on the Solomon Islands during World War II, helped rescue the crew of PT 109 (including then-Lieutenant John F. Kennedy). Oval Office, White House, Washington, D.C. - May 1st, 1961. Photo: Abbie Rowe. White House Photographs. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston

A memorial lighthouse was erected to honour the Coast Watchers at Madang on the northern coast of Papua New Guinea in 1959.

On August 23rd 1945 G J McPhee is a Lieutenant in the 55/53 Australian Infantry Battalion. He was finally officially discharged on September 29th, 1946, having served for 48 months, or 60 months if you include his pre 1941, aged 21, enlistment in the AMF.

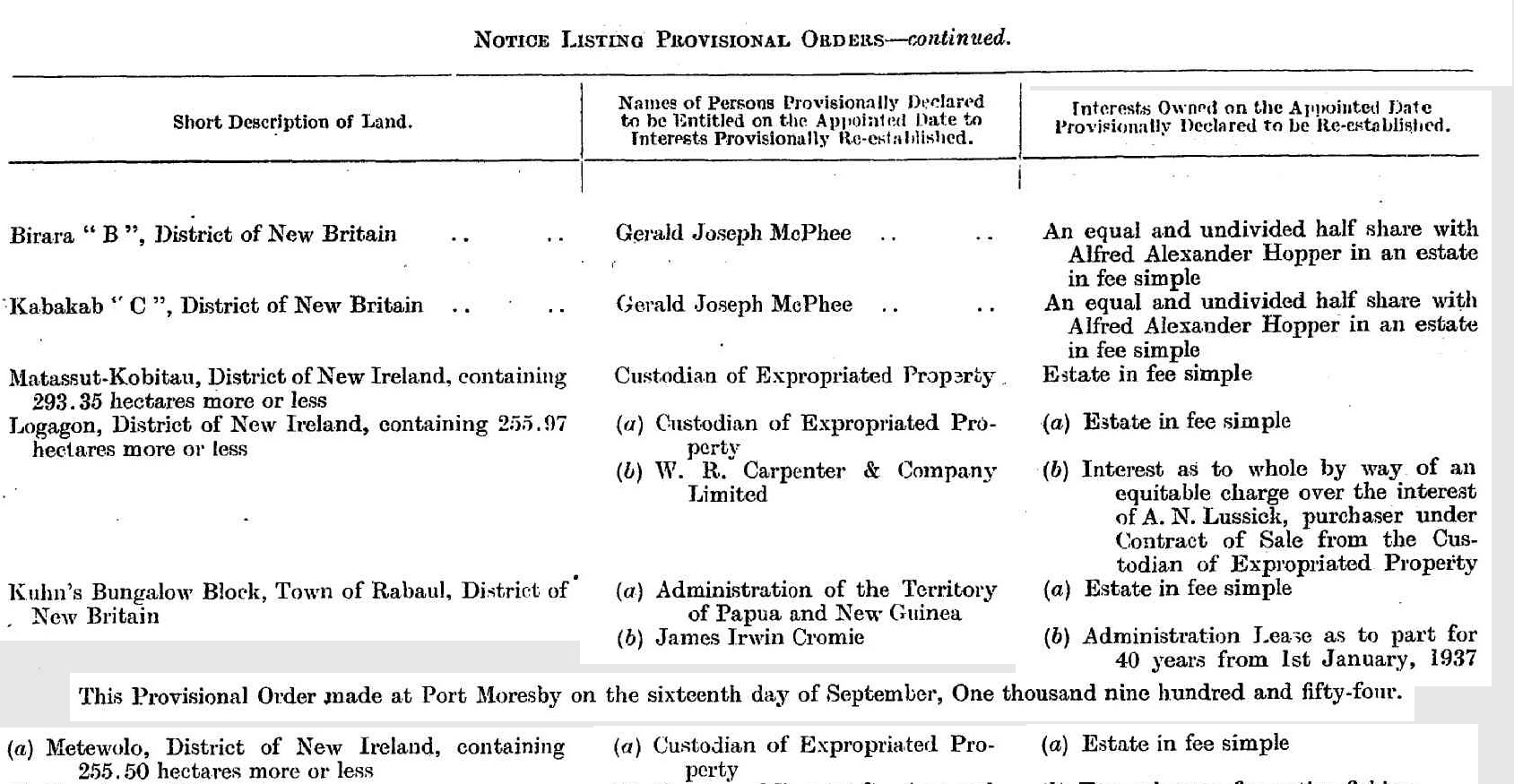

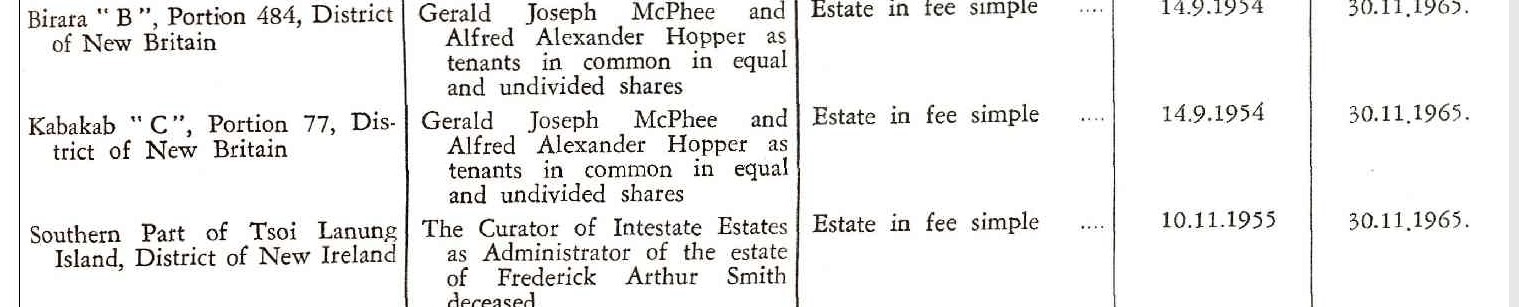

Gerald was busy heading back to New Guinea prior to that official demobilisation though. Rabaul had been destroyed by the offensive actions taken by the Japanese and then the Australians and Americans in retaking the place. It needed rebuilding and for its pre-war produce to once again flow and provide for those at PNG as well as where it was sent. Copra was one of the main exports.

The last page of his war record shows:

By Feb 6-8, 1946, he arrived back via Qantas airlines as Captain McPhee and was definitely there again by late October 1946: by Qantas as part of the ANGPCB [Australian New Guinea Production Control Board] - Staff - McPhee, Gerald J [0.5cm] Contents date range; 1946 - 1947

Qantas flight in: OCT. 23; Mr. R. H. Hawke, Mr. V. C. Dixon, Mr. D. E. Ronald, Mr. E. A. Avery, Mrs. I. P. Hanrahan (and child), Mr. P. M. Brown, Mr. J. A. Robinson, Mr. G. J. McPhee, Mr. H. E. Lovett-Cameron, Mr. W. Brown, Mr. R. A. Thrift, Mr. G. B. Clark, Mr. W. E. P. Luke, Mr. Hilderbrand, Mr. F. de Hesselle. Pacific islands monthly : PIM. Vol. XVII, No. 4 ( Nov. 18, 1946)

Once he left the Australian New Guinea Production Control Board he set himself up with a New Guinea plantation producing copra for the Australian market - although he would take on a partner later on before returning to being a solo producer. He returned to Bougainville and the New Ireland area.

Gerald was alike other Australians who went to New Guinea after WWII - some because they 'could not settle' after all they had experienced - Walter 'Wal' Williams stated this was what he did; went to New Guinea [7.]. Others, like Gerald, returned because what they fell in love with the place, its peoples, the freedoms and the opportunities available. He had, after all, spent some of his most dangerous times in his then short life with the real New Guinea and Bougainville peoples on their trails through their places, and had come from a farming family. This would persist throughout his life - this love of the outdoors and growing produce.

In June 1948 he was heading back to Sydney:

Late DLO at Manus, Mr. G. Corlass, with Mrs. Corlass, daughter Jill and small son, have now taken up residence here. Visitors have included Mrs. Butler from Angoram, and Gerry McPhee, en route from Angoram to Sydney, where he is to join the benedicts. – June 1948 Issue. FIRST POST-WAR WEDDING IN WEWAK, Pacific islands monthly : PIM Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-329950948

The definition of benedict in this sense is; 'a newly married man (especially one who has long been a bachelor)'.

Gerry McPhee, G J McPhee's son, still living at Mosman, confirmed his grandfather had to go an collect His M.C. as his son had already returned to New Guinea and to work:

He was back in Spring 1949, this time for his wedding:

Plantation home for Sydney bride

Mr. and Mrs. Gerald McPhee, whose marriage took place at St. Philip's Church, Church Hill, yesterday, will sail in Bulolo in October to make their home on Bjaul Island in the New Ireland group, where Mr. McPhee has a copra plantation. Mrs. McPhee was formerly Miss Margaret Murphy, second daughter of Mr. and Mrs. J. Murphy, of Dulwich Hill. Mr. McPhee is the son of Mr. G. J. McPhee and the late Mrs. McPhee, of Mosman. Miss Elaine Murphy attended her sister, and Mr. Stanley Neil was best man. A reception followed at Amory, Ashfield. Plantation home for Sydney bride (1949, September 10). The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW : 1931 - 1954), p. 10. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article248092707

Dyaul Island (also Djaul) is an island in New Ireland Province, Papua New Guinea. Its area is 100 km2. The inhabitants live mainly in seven villages, and frequently visit Kavieng, the capital of the province, for supplies or to sell produce and fish. There are two languages, not counting Tok Pisin, spoken on Dyaul; Tigak and Tiang. Tigak is widely spoken on the western end of the island in two villages. Tiang is spoken across the remainder of the island.

Gerald McPhee from Djaul Island, was married to Margaret Murphy, of Dulwich Hill, on September 9 and sails in Bulolo this month for his island off the New Ireland coast. MAGAZINE SECTION Territories Talk-Talk, Pacific islands monthly : PIM Retrieved October 1949 Issue from http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-372976049

Miss A. McPhee, a trained nurse, who has been working in East Africa and, lately, in Lebanon, reached Sydney early in May on her way to New Guinea. She left for New Britain by air on May 10 to stay with her brother, Mr. Gerald McPhee, planter, of Kokopo. Fiji Copra Producers [?]ut £97,000 [?] Govt. Loans, Pacific islands monthly : PIM Retrieved June 1952 Issue, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-332834090

Copra plantations in New Guinea: Early colonialists

Copra is the dried, white flesh of the coconut from which coconut oil is extracted. Traditionally, the coconuts are sun-dried, especially for export, before the oil, also known as copra oil, is pressed out. The oil extracted from copra is rich in lauric acid, making it an important commodity in the preparation of lauryl alcohol, soaps, fatty acids, cosmetics, etc. and thus a lucrative product for many coconut-producing countries. The palatable oil cake, known as copra cake, obtained as a residue in the production of copra oil is used in animal feeds. The ground cake is known as coconut or copra meal.

In 1884, German settlers arrived in eastern New Guinea (now Papua New Guinea), and planted Coconut palms (Cocos nucifera) for the production of copra, the dried flesh of the coconut. They established the colony of German New Guinea in the north eastern quarter of the island and numerous coconut plantations around coastal areas. They were afraid of venturing too far inland. To counter the growing German presence in the region, the Australian state of Queensland established the Territory of Papua as a de facto possession covering approximately the south east third of the island. Both the Queensland and German plantations thrived, providing opulent living conditions for the expatriates. Grand mansions were built on the plantations, complete with luxury furnishings. Much of the labour was performed by New Guinea natives. The towns of Port Moresby and Rabaul were founded as a result of the economic activity surrounding the plantations.

In 1914, Australia sent a small military force to capture the towns of Kokopo and Rabaul. Two Germans were killed in the process, while the remaining German plantation owners were initially sent back to work on their plantations. The 1919 Treaty of Versailles saw Germany lose all its overseas colonies, including German New Guinea. It became the Territory of New Guinea, a League of Nations Mandate Territory under Australian administration.

Kokopo is the capital of East New Britain in Papua New Guinea. The capital was moved from Rabaul in 1994 when the volcanoes Tavurvur and Vulcan erupted. Kokopo was known as Herbertshöhe during the German New Guinea administration which controlled the area between 1884 and 1914. From: https://en-academic.com/dic.nsf/enwiki/8290480

In the Issues of the Pacific Islands Monthly we garner glimpses of his life in New Guinea then and his being part of those communities:

UNHAPPY PLANTERS IN SOLOMONS

Resentful of British Administration and Policy

(CONDITIONS in the British Solomons provide a good example of what happens in an under-developed British tropical territory under a Socialist regime.

Before World War II, it was the policy of the British Colonial office to encourage private enterprise to go into such places and develop their resources. There was not much to develop in the Solomons then —copra was not greatly in demand—but a good type of planter was at least assisted to make his home there.

To-day, there appears to be nearly double the pre-war number of public servants in BSI; but the production of copra —in quantity—is probably no more than half the pre-war volume. The Administration’s pre-war policy of encouraging private enterprise has been replaced by a laissez-faire attitude that is taken to mean that, while officialdom is indifferent about the condition of non-official Europeans, it is intensely pre-occupied with native welfare.

The net result, of course, is seen in three things—discontented and resentful Europeans, spoiled natives and a heavy additional burden upon the British taxpayer. Only a handfull of the planters and traders who were driven out by the war have returned to the Solomons.

In some respects, conditions in BSI are almost a duplicate of conditions in Papua-New Guinea. In the latter country, the Socialist policy, directed from Canberra, discourages private enterprise, spoils the natives, makes non-official Europeans non-co-operative and resentful, and throws an enormously increased burden upon the Australian exchequer. Before the war, Papua-New Guinea was almost self-supporting, and BSI was only a little less so.

IN a comparison, however, the planters who have returned to the Solomons are worse off than the Australian non-officials in Papua-New Guinea.

The Australians got war damage compensation from a fund created for that purpose in war-time; BSI got nothing at all. The Australians escape taxation — although they are heavily taxed through import duties —but they lose from £10 to £I2A per ton on their copra. The latter is taken from them by Canberra as (a) export tax and (b) some mysterious deduction —which Canberra so far has refused to explain—called “stabilisation fund.” The BSI planters have to pay an export tax; and, also, they are savagely mulcted in income tax. It is only 1/3 in the £ on the first £1,500 of income; but, after that, the rise is so steep that, around £5,000, a big trader can lose a large part of his income.

The collection of income tax in BSI — something new since the war —is an evil imposition. Income tax should be imposed only when the citizen receives, from his government, substantial amenities and encouragement. BSI is such a primitive country that it gives its European residents practically nothing in the way of amenities —someone said lately that “The BSI, to-day, is at the same stage of development as England was in the time of the Romans.”

"WE are so sick of administrative pin-pricks, and official indifference to European welfare, that we should welcome any move for transfer to Australian government,” said a BSI planter recently. “We pay an import tax of 17per cent, an export tax of 15 per cent, on our copra, and now we are faced with heavy income tax.”

Other residents say that, although non-officials, who lost everything, get no war- damage compensation at all, all officials who were affected by the Jap invasion have been given, secretly, a sum of £5O each, as compensation for the loss of their personal effects.

It is anticipated that there soon will be a new Resident Commissioner in the Solomons (Mr. Noel, who has been away on long leave, is not expected to return, and Mr. A. Germond, MBE. has been acting RC); but no change in policy is expected while the Socialists rule Britain.

LAST TWO JAPS

Give Themselves Up At Saidor, NG

From Our Own Correspondent PORT MORESBY, Sept. 6.

TWO Japanese walked into the Government post at Saidor, northern New Guinea, a few days ago, after having lived among the natives of that area for five years without being discovered. The natives sheltered them, and never once mentioned their presence to Government officers, who patrol the area regularly.

When they gave themselves up the Japs were barefooted, and their clothing was falling to pieces; but, apart from slight malnutrition, their health was good.

Speaking in Pidgin English they told their story yesterday to District Officer J. K. McCarthy, at Madang, where they were taken from Saidor by trawler.

They said they deserted their unit during the Japanese retreat and joined tribes in the Saruwaget Range, inland from Saidor. After several months they threw away their weapons and went completely native, hunting native fashion and growing native foods. A native medical orderly supplied them with quinine and other drugs. They said their friends had told them the war was over but they were too frightened to emerge from hiding until a few days ago.

On Thursday, they will be flown to Manus to join the Japanese war criminals who are imprisoned there.

Seventeen Japs have now given themselves up in the Madang area since the war ended and, according to these last two, there are no more in hiding.

Pacific islands monthly : PIM. Call Number HSW 1363, Created/Published [Sydney : Pacific Publications, 1931-2000 Issue Vol. XX, No. 2 (Sept., 1949). UNHAPPY PLANTERS IN SOLOMONS Resentful of British Administration and Policy, Pacific islands monthly : PIM Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-372988235 and LAST TWO JAPS Give Themselves Up At Saidor, NG, Pacific islands monthly : PIM Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-372988262

MR. HENRY LOVETT CAMERON