October 16 - 22, 2022: Issue 558

Depoliticising Taxpayer-Funded Advertising - New Grattan Institute Report Recommends Political Parties Should Repay Taxpayer-Funded Politicised Advertising

Report released October 9, 2022

by Danielle Wood, Kate Griffiths, Anika Stobart - Grattan Institute

Abuse of taxpayer-funded advertising is rife in Australia, with governments routinely spending public money to spruik their own achievements, especially in the lead up to elections.

Download the report Download the chart data

Of the nearly $200 million spent each year by the federal government on advertising, nearly $50 million is spent on politicised campaigns.

Over the past 13 years about $630 million, or a quarter of all federal campaign advertising, was spent on campaigns that spruiked government achievements – and spending spiked on the eve of each federal election.

This is a problem on both sides of politics, and at federal and state level. Of the 10 most expensive politicised federal campaigns in the past 13 years, half were approved by Labor governments and half by Coalition governments. Auditors-general often criticise state government advertising campaigns too.

In the lead up to the 2019 federal election, the government spent about $85 million of taxpayers’ money on politicised advertising campaigns – on par with the combined spend by political parties on TV, print, and radio advertising.

Weaponising taxpayer-funded advertising for political advantage wastes public money, undermines trust in politicians and democracy, and creates an uneven playing field in elections.

Australia needs tougher rules and tighter processes at federal and state level to prevent governments from exploiting taxpayer-funded advertising.

Government advertising campaigns should be allowed only where they are necessary to encourage specific actions or drive behaviour change. Campaigns that promote government policies or programs, without a strong call-to-action, should be prohibited.

An independent expert panel should assess all government advertising campaigns before they are launched. If the panel deems a campaign to be politicised, or otherwise not value for money, it should not run.

These rules and processes should carry real penalties. If an Auditor-General finds that an advertising campaign was approved by the minister without certification from the independent panel, or that the government changed the campaign after certification, the governing party should be liable to pay back the entire cost of the campaign.

Sadly, Australians cannot rely on the goodwill of ministers to prevent misuse of public money on politicised advertising.

It’s time to ensure that taxpayer-funded advertising is solely for the benefit of the public, not politicians.

This is the third and final report in Grattan’s New politics series on misuse of public office for political gain. The first, published in July, tackled politicisation of public appointments, and the second, published in August, focused on pork-barrelling of government grants.

Every day, federal and state governments make decisions that affect the lives of Australians. Australia’s prosperity depends on these decisions being made in the public interest, rather than the decision-maker’s self-interest or party-political interests.

Elections and anti-corruption laws provide important checks on the conduct of governments. But there are thousands of decisions made by ministers and public officials where these defences provide only limited constraint. Historically, Australia has relied on a combination of targeted rules and norms, particularly ministerial accountability, to ensure that smaller and less-visible decisions are made in the public interest.

Grattan Institute’s New politics series of reports shows that in many cases federal and state governments have subverted these checks and made decisions with an eye to party-political interest.

This report shines a light on misuse of taxpayer-funded advertising. Politicisation of taxpayer-funded advertising wastes money, creates an uneven playing field, and over time can erode trust in politicians and democracy. It is against the public interest.

Taxpayer-funded advertising is for the government of the day to communicate important information to the public, such as encouraging behaviour change, and promoting compliance with laws. These campaigns should have a clear public purpose and should offer value-for-money in achieving their purpose.

Justified taxpayer-funded advertising might include, for example, public campaigns to remind people to get their COVID-19 booster shots, or information on how victim-survivors of family violence can get help.

Taxpayer-funded advertising is different to political advertising, which is funded by political parties themselves, not the taxpayer (see Box 1).

But sometimes governments use taxpayer-funded advertising to communicate political messages (see Chapter 2).

Box 1: Political advertising is different

Political advertising seeks to promote a political party, candidate, or political agenda. These ads are usually funded by political parties themselves, but can also be funded and distributed by others who want to influence voters and can afford to do so.

Political ads appear with authorisation of the political party (or the third party) that funded it, whereas taxpayer-funded ads appear with authorisation of the government.

When it comes to the content of political ads, there is almost no oversight. In contrast, taxpayer-funded ads are supposed to be apolitical and objective. This report is focused on taxpayer-funded advertising, not political advertising.

Governments spend big on advertising

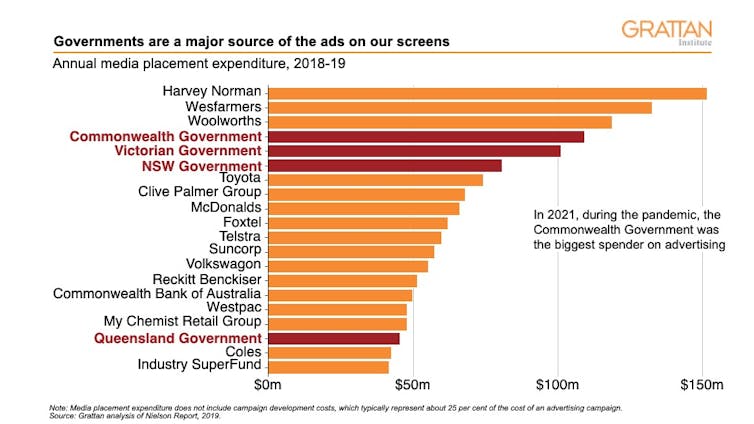

Over the past 10 years, Australian governments have spent nearly $450 million a year, on average, on advertising campaigns. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, the federal, NSW, and Victorian governments each spent more than most big private companies, including Toyota, McDonald’s, and Foxtel (see Figure 1.1).

Over the past 25 years, the federal government has spent on average about $200 million a year on advertising (in today’s dollars). Spending fluctuates with events and elections, but has remained relatively stable over this period.

Australia’s federal government advertising spend is much higher, per person, than similar countries such as the UK and Canada.

The biggest topics for federal government advertising spending are defence force recruiting and health (see Figure 1.2). Typical state government advertising campaigns include, for example, workplace health and safety, road safety and emergency management, and health and family services.

Much of the spending is on important public messages, but not all of it. Some campaigns are politicised (see Chapter 2).

Politicisation of taxpayer-funded advertising is against the public interest

Australians place trust in our elected officials to make decisions on our behalf, including on how public funds are spent. This trust is reinforced by a raft of rules and guidelines to help public officials make decisions that ‘advance the common good of the people of Australia’.

Codes of conduct for ministers at both federal and state levels outline the ethical standards required in the job, given their position of privilege and wide discretionary powers. These codes require ministers to wield their powers solely in the public interest.

Despite these rules and norms, federal and state governments on both sides of politics have sometimes spent public money to meet partisan goals rather than purely in the public interest. Politicisation of taxpayer funded advertising is another example of this.

As Professor Joo-Cheong Tham argues: ‘Government advertising to reinforce positive impressions of the incumbent party is a form of institutional corruption – it is the use of public funds for the illegitimate purpose of electioneering’.

Politicised advertising is a waste of taxpayer money

Politicising public money is wasteful because it means there is less money to spend on higher-value projects or purposes.

Between 2008-09 and 2020-21, we estimate that $630 million – a quarter of all taxpayer-money spent on campaign advertising – was spent on politicised campaigns. This equates to nearly $50 million a year on average. That money could instead have been spent on more valuable campaigns, or on higher-value spending to improve the lives of Australians.

The mere perception that an advertising campaign is politicised is enough to undermine its effectiveness. As noted by the Queensland Audit Office:

Messages that are seen to be intended to affect public opinion about the political party in government (rather than about the government services being delivered) have the potential to diminish: the value of the messages being conveyed; the effectiveness of the expenditure; [and] public perception of the legitimacy of the advertising campaign.

Governments already get a lot of free publicity through traditional media and have large reach through social media. If they want to convey a political message outside of these channels they should advertise using party funds, rather than drawing on the public purse.

Politicised advertising creates an uneven playing field

Politicised advertising can create an uneven playing field, especially close to elections. Governments exploit their incumbency to spend big on advertising to boost their image. This creates an unfair disadvantage for opposition parties and candidates.

In the nine months leading up to the 2019 federal election, political parties spent a combined $82 million on party-funded TV, print, and radio advertising. Over the same period, the federal Coalition government spent about $85 million on taxpayer-funded politicised advertising campaigns. Opposition parties and independent candidates have no such opportunity to use taxpayer money to achieve saturation coverage.

Politicised advertising undermines public trust

Misuse of government advertising for political purposes also contributes to an erosion of public trust. Using taxpayers’ money to promote a government’s reputation makes it obvious to citizens that governments are willing to put their own political interests ahead of the public interest.

This conduct contributes to cynicism about politicians’ behaviour and motives more broadly.

Such cynicism is on the rise. Three-quarters of Australians suspect governments make decisions for political gain over the public interest, up from 58 per cent 15 years ago. Over this period there has also been a rise in the proportion of people not satisfied with democracy (Figure 1.3). At the 2022 federal election there was a record vote for minor parties and independents.

Trust matters to the legitimacy of government and its ability to get things done.

Politicising taxpayer-funded advertising can undermine trust in government messaging more generally. It could diminish the government’s ability to effectively communicate important messages, such as encouraging people to get a vaccination.

Existing rules and norms are not enough. Politicisation of taxpayer funded advertising, by federal and state governments, still appears common despite many scathing audit reports.

Some politicians even defend this behaviour. For example, former prime minister Scott Morrison defended spending on taxpayer-funded advertising in the lead up to the 2019 federal election as ‘entirely appropriate for Australians to understand what their government is doing’. And after the Victorian Auditor-General found that the state government’s Our Fair Share campaign was politicised, Premier Daniel Andrews said: ‘The Auditor-General’s entitled to their view, [but the] government believes we complied with all relevant matters and we wouldn’t hesitate to run that campaign again’.

Given the limitations set out above, there is a case to codify expectations and to introduce more checks and balances on the use of public money.

There are three main characteristics of politicisation

Taxpayer-funded advertising is never as overtly political as party-funded advertising, but still often contains elements aimed at securing an electoral advantage. We have categorised campaigns as politicised if they promote a party, spruik the government’s policies, or spending is heavily concentrated in the period immediately before an election (see Box 2). Some campaigns meet two or more of these characteristics (see Table 2.1).

For example, the stated purpose of the $29 million Powering Forward campaign (2017 to 2019) was to raise awareness of the federal government’s efforts to reduce power costs, and to provide information about how people could lower their energy bills. But this campaign had many questionable elements: the media release launching the campaign contained overtly political statements, spending on the campaign spiked in the lead-up to the 2019 election, and government achievements dominated the messaging, with little useful information for people on how to reduce their own power bills.

When a campaign is politicised, it doesn’t necessarily mean it was conceived solely for a political purpose. But the problem is there shouldn’t be any confusion – government messages should not morph into political ones.

Promoting a political party

Naming political parties and including party logos in taxpayer-funded advertising are clear cases of politicisation. These ads should be funded by the party, not the taxpayer.

Usually it is more subtle, such as the use of party colour schemes, slogans, or political tone. And sometimes politicians deliberately blur the lines on social media (see Box 3 on page 19).

Government guidelines prohibit advertising that promotes party-political interests (see Appendix). But it can still slip through: our estimates indicate about $80 million was spent over the past 13 years on campaigns that promoted political parties (see Figure 2.3).

In early 2022, the then federal government published ads in major newspapers that used a blue colour scheme – similar to the Liberal Party blue – alongside a vague statement promoting the government’s economic policy: ‘Australia’s Economic Plan: Employment is up, so we’re taking the next step’ (see Box 4 on page 20).

Party slogans in government ads also blur the lines between government messaging and party messaging. In 2015-16, the federal government was accused of using variations of its party slogan ‘There’s never been a more exciting time to be Australian’ in its National Innovation and Science Agenda campaign, which aired while the government was pushing its innovation package through parliament.

A political tone in advertising also points to politicisation. In 2022, the Victorian Auditor-General found that most of the ads in the Labor state government’s Our Fair Share campaign were political. The campaign advocated for more Commonwealth funding for Victoria and the ads used emotive, politicised language criticising the then federal government, such as ‘don’t let Canberra short-change our kids’

Close to elections

Taxpayer-funded advertising campaigns that are timed to roll out just before elections would appear to confer a political advantage. There is no reason Australians should see more public-interest campaigns in an election period, compared to a non-election period.

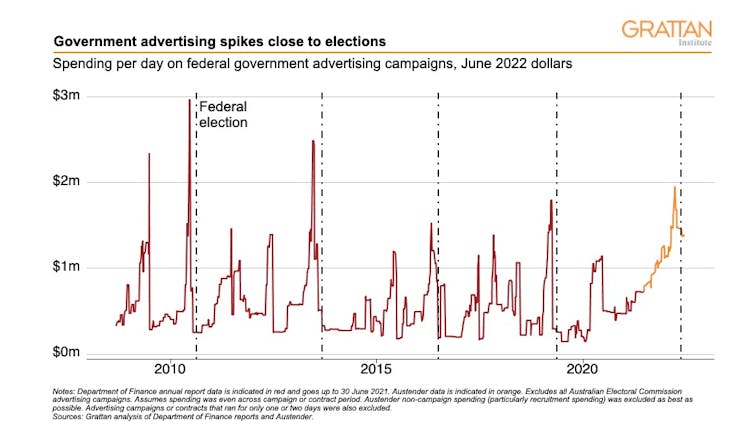

Yet in the lead up to each federal election, federal government spending on advertising spikes (see Figure 2.4). Between 2008-09 and 2020-21, nearly $300 million was spent on taxpayer-funded campaigns timed for an election (see the middle column on Figure 2.3).

Election-timed campaigns often run exclusively during the pre-election period, and not at any other time during that government’s term in office.Some campaigns also appear timed to run before by-elections, such as the five ‘Super Saturday’ by-elections in 2018.

An otherwise-legitimate campaign might be strategically run pre-election to encourage a positive impression of the government. But usually pre-election advertising also contains messages that look politically-motivated – promoting the government’s policy platform on key election issues. For example:

- In the months before the 2013 federal election, the Anti-people Smuggling communications campaign was run at a time when ‘stopping the boats’ was a live debate.

- Before the 2019 federal election, the Tax and the Economy campaign promoted the government’s tax cuts in line with the government’s ‘lower taxes’ election platform (see Figure 2.5).

- Before the 2020 Queensland election, the state government ran a campaign spruiking the government’s COVID-19 economic recovery plan.

- Before the 2022 South Australian election, the state government ran a campaign spruiking its investments in the health system. Performance of the health system was a key state election issue.

Spruiking the government

Spruiking the government of the day is the most common way to politicise taxpayer-funded advertising.

Many taxpayer-funded advertising campaigns use messaging that creates a positive image of the government’s performance. Between 2008-09 and 2020-21, about $580 million – or 20 per cent of all expenditure on government advertising campaigns – was on these sorts of campaigns that deliver positive messages about the actions and policies of the government of the day without a strong call-to-action (see the first column in Figure 2.3).

No call-to-action

Notably, many of the campaigns that spruik government policies lack a call-to-action which might justify them on public-interest grounds.

The $39 million Building Our Future campaign aimed to promote the federal government’s investments in transport infrastructure (see Table 2.1 on page 16). But there was nothing specific that the government needed people to do. Instead, the campaign generated feel-good messages about the infrastructure pipeline. The Australian National Audit Office found that the campaign’s messages exaggerated the federal government’s involvement in transport infrastructure.

Nor were there any calls-to-action in the Anti People-Smuggling communications campaign, used by both major parties when in office, which included ads in Australian newspapers about the government’s tough stance on boat arrivals (see Box 4 ).

State governments do it too. For example, the WA Bigger Picture campaign, which ran from 2012 to 2016, promoted the government’s investments in infrastructure projects, such as upgrading a regional boarding school. And the Queensland government spent more than $8 million on two campaigns in 2020-21 to ‘inform Queenslanders of the state’s recovery plan’.

Garnering support for unimplemented policies

Governments also appear to use taxpayer-funded advertising to garner support for unimplemented policies. For example, the $24 million Clean Energy Future campaign (2011) ran before the carbon tax reforms were passed. The $23 million National Plan for School Improvement campaign (2013) ran before the reforms were passed by parliament, and in states that had not signed on. And the $10 million Higher Education Reforms campaign (2014-15) ran before the reforms failed to pass the Senate and were ultimately dropped.

This occurs at state level too. The $4.5 million NSW ‘Stronger Councils, Stronger Communities’ campaign (2015-16) sought to build support for council mergers. The advertising was expected to ‘increase confidence of Members of the Legislative Assembly and Members of the Legislative Council to support the reform legislation’.

These sorts of campaigns demonstrate the uneven playing field for governments and oppositions. And, as the ANAO has said, campaigns on unimplemented policies risk providing inaccurate information to the public.

A better approach to taxpayer-funded advertising

Australia needs better rules and processes to prevent politicisation of taxpayer-funded advertising. The current rules and processes are weak and largely unenforceable. The new federal government has made checks and balances even weaker.

Australia’s federal and state governments should legislate tighter rules that limit the scope of taxpayer-funded advertising campaigns. Campaigns should run only if they encourage specific actions or seek to drive behaviour change in the public interest. Campaign material should not promote a party or the government. And campaigns should be timed to run when they will be most effective, not to cluster immediately before elections.

But better rules alone will not be enough. An independent panel should assess whether final campaign materials comply with the rules. And if the government subverts the process, the governing party should be penalised: the governing party, not taxpayers, should be liable to pay the costs of politicised advertising.

Better rules

The current rules for taxpayer-funded advertising in Australia are largely ineffective in preventing politicisation (see Chapter 2). They look good on paper, but they are mostly voluntary ‘guidelines’, and largely unenforceable (see Appendix).

The rules should be strengthened across all jurisdictions. They should be made mandatory through legislation, and passed by parliament. They should seek to minimise the three characteristics of politicisation identified in Chapter 2, and they should be able to be objectively applied.

Campaigns should have a legitimate purpose

Taxpayer-funded advertising should be specifically reserved for situations where an advertising strategy is necessary to encourage specific actions or drive behaviour change.

Legitimate purposes could include:

- Encouraging people to use public sector products and services, such as public transport options, employment incentives, or services for victim-survivors of family violence.

- Promoting public safety or personal security, such as bushfire or workplace safety.

- Encouraging healthier living, such as anti-smoking or anti-drug campaigns.

- Communicating community obligations, such as how to enrol in elections, or how to fill out the Census survey.

- Promoting a shift in community attitudes, such as positive sentiments about the value of teachers.

- Attracting tourists, such as international or state-based tourism campaigns.

- Recruiting staff to government roles, such as recruiting for the defence force.

Illegitimate purposes could include:

- Informing the public of government policies that don’t require any action or behaviour change, such as automatic tax cuts.

- Informing the public of government policies, where the call-to-action is only a small part of the ad or not effectively communicated (such as visiting a government website).

- Building awareness of government achievements, such as its economic record or its investments in infrastructure.

- Promoting unlegislated policies to influence public sentiment.

- Promoting government positions or policies to counter dominant public narratives or opposition policies.

- An otherwise-legitimate campaign, specifically timed to run to provide political advantage (such as immediately before an election, see Section 3.1.2).

Of course, Australians have a right to information about what the government is doing, and how it affects them. But governments already have a huge platform to communicate with the public about their policies and programs through the parliament and the media. They don’t need a multi-million dollar advertising strategy paid for by the public.

Campaign materials should not promote a party or the government

Existing rules at federal and state level require that campaign materials be objective, factual, and free of political argument. Advertising campaigns should not influence support for a political party, and should not name politicians or parties, or use party logos or slogans.

Yet in practice, campaigns that spruik the government – or even use party colours – do not fall foul of these prohibitions, despite clearly conferring a political advantage (see Chapter 2).

A broader prohibition is needed, as adopted in Victoria, the ACT, and the UK.

For example, a campaign that spruiks the government’s investment in infrastructure projects, and informs the public in general terms of consequent road disruptions, should not pass this test. Broad promotion of government investment in infrastructure is political because the government is seeking to enhance its reputation in the public eye. On the other hand, a more targeted campaign focused on messaging about specific road disruptions and alternative routes during construction would be unlikely to raise concerns.

Better processes

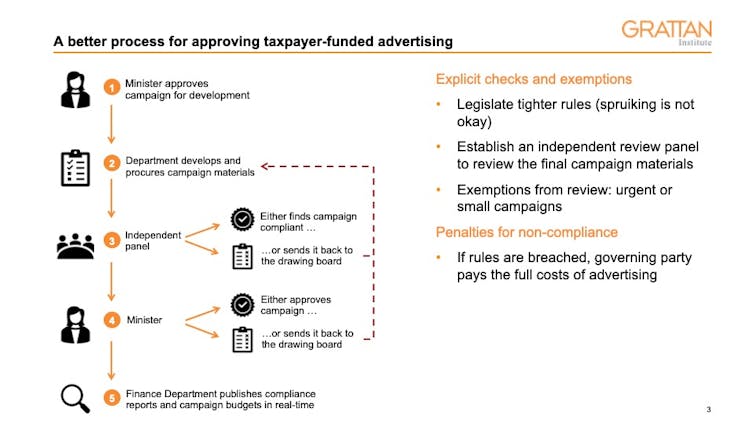

The current approval processes for taxpayer-funded advertising are not working (see Box 6 for an outline of the federal government’s weak processes). Many campaigns that have political elements are still being approved at federal and state levels (see Chapter 2). A better process is needed across nearly all jurisdictions to ensure campaigns are run only if they comply with the rules (see Figure 3.1).

An alternative approach to reduce politicised advertising is to impose a cap on the amount that can be spent on taxpayer-funded advertising each year. This is a crude option because it could constrain legitimate as well as politicised advertising. However, if our recommended process isn’t adopted, an expenditure cap is a second-best alternative to reduce the harms from politicised advertising.

An independent panel should check compliance

An independent panel should assess compliance of final campaign materials against the rules (see Section 3.1), and its compliance reports should be made public.

If the independent panel certifies that the campaign is compliant, the relevant minister could then either approve the final campaign, or send it back to the drawing board (see Figure 3.1). The minister should not be able to change the campaign materials after the panel has signed off on them, but they could still decide not to run the campaign.

Without the scrutiny of an independent panel, campaigns are at risk of politicisation. Independent scrutiny also helps ensure that campaigns are value for money, and will be effective at achieving their goal.

Merely having an in-house departmental committee, as NSW, Victoria, Queensland, and WA have, does not fully guard against political intervention.

The new panel must be truly independent – not hand-picked by a minister. The members should be appointed in a merit-based, transparent process, as recommended in Grattan Institute’s report New politics: A better process for public appointments.

The independent panel should be made up of experts. Members should have a mix of relevant skills, including media and communications experience.

While some argue this review role should be handed to Auditors General, we do not think this appropriate. This was the case at the federal level between 2008 and 2010, but an independent review found that it ‘[drew] into question the independence of the Auditor-General and potentially create[d] conflicts of interest’.

Campaign costs and compliance should be reported in real-time

Federal and state finance departments should report on campaigns in real-time. This should include approved and final campaign budgets, run-time, and independent panel compliance reports.

The current annual reporting in some jurisdictions (see Appendix) does not provide timely transparency. Annual reports are often published six months after the end of the financial year, so up to 18 months after a campaign has run.

Better enforcement and real penalties

Auditors-General should conduct regular audits of government advertising. Funding for federal and state audit offices should be increased to resource regular reporting.

If an Auditor-General finds that a campaign was approved by the minister without certification from the independent panel, or the minister changed the campaign after certification, the governing party should be liable to pay the entire cost of the campaign. If the governing party wanted to challenge the Auditor-General’s findings, it would have to mount an appeal to the relevant court.

Better rules alone are not enough. Our proposed penalty would provide a powerful disincentive for any government tempted to break the rules.

The new rules, processes, and penalty should be legislated to ensure current and future governments are held accountable.

Australians cannot rely solely on weak rules and the goodwill of ministers to prevent misuse of government advertising. It is time for stronger safeguards to protect the public interest.

Wood, D., Stobart, A., and Griffiths, K. (2022). New politics: Depoliticising taxpayer-funded advertising. Grattan Institute. ISBN: 978-0-6454496-8-6

All material published or otherwise created by Grattan Institute is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License

All governments are guilty of running political ads on the public purse. Here’s how to stop it

Kate Griffiths, Grattan Institute; Anika Stobart, Grattan Institute, and Danielle Wood, Grattan InstituteIf you watch TV or read the paper, you’ve probably seen ads spruiking the achievements of the federal or state government – from the next big transport project to how they’re reducing the cost of living. While some government ads are needed, many are little more than thinly-disguised political ads on the public dime.

A new Grattan Institute report shows both Coalition and Labor governments, at federal and state levels, use taxpayer-funded advertising for political purposes. But there is a way to stop this blatant misuse of public money.

Why Do Taxpayers Fund Advertising?

Federal and state governments combined spend nearly $450 million each year on advertising. And the federal, NSW, and Victorian governments individually spend more than many large private companies such as McDonald’s, Coles, and the big banks (Figure 1).

Governments run advertising campaigns to communicate important public messages and to ask us to take action. For example, in recent years we’ve seen a lot of federal and state government advertising about COVID-19 restrictions and how to get vaccinated.

These health messages are in our individual and collective interests, so it is appropriate that governments communicate those sorts of messages and that we – the community – fund them. But this is not true of all taxpayer-funded advertising.

Governments Take Advantage Of This Pot Of Money

Our analysis of every federal government advertising campaign over the past 13 years reveals that many were politicised. On average, nearly $50 million each year was spent on campaigns that conferred a political advantage on the government of the day – about a quarter of total annual spending.

Taxpayer-funded advertising is never as overtly political as party-funded advertising, but it still often contains elements aimed at securing an electoral advantage. The three main signs of politicisation we identified in federal and state government advertising were:

campaign materials that included political statements, party slogans, or party colour schemes. For example, before the last federal election, the federal government published ads in major newspapers that used the Liberal Party blue, alongside a vague statement: “Australia’s economic plan. We’re taking the next step”

campaigns that were timed to run in the lead-up to an election, without any obvious policy reason for the timing. Spending on government advertising consistently spikes in the lead up to federal elections (see Figure 2)

campaigns that spruiked the government’s policies or performance and lacked a meaningful call-to-action. For example, the Queensland government spent more than $8 million on two campaigns in an election year to “inform Queenslanders of the state’s recovery plan”.

Many federal and state campaigns contained multiple elements of politicisation – using party colours, spruiking government achievements, and running on election eve.

How To Depoliticise Government Advertising

Taxpayers should not be footing the bill for political messages. It’s a waste of public money, it undermines trust in important government messaging, and it can create an uneven playing field in elections.

In the lead up to the 2019 election, the federal government spent about $85 million of taxpayers’ money on politicised campaigns – on par with the combined spend by political parties on TV, print, and radio advertising. Oppositions, minor parties, and independents have no such opportunity to exploit public money for saturation coverage.

There are plenty of other ways governments can spruik their policies without drawing on the public purse. Ministers can use Parliament, doorstop interviews, traditional media, and their own large social media reach to promote their policies. And if governments want to convey a political message outside of those channels, they can advertise using party funds.

We recommend stronger rules to limit the scope of taxpayer-funded advertising. Campaigns should run only if they encourage specific actions or seek to drive behaviour change in the public interest. This would allow recruitment ads, tourism campaigns, bushfire or workplace safety campaigns, and anti-smoking ads – to give a few examples. But it would not allow ads that simply promote government policies.

Campaign materials should obviously not promote a party, or the government. And campaigns should run when they will be most effective, not when they will provide a political advantage (such as immediately before an election).

These rules should be enforced by an independent panel, which would check the final campaign materials. The panel should have the power to knock back campaigns that are not compliant – whether they are politicised, or more generally don’t offer value for money (see Figure 3).

Finally, we recommend a simple but strong penalty for breaking the rules: the governing party, not taxpayers, should be liable to pay the costs of any advertising that has not been ticked off by the independent panel. This would discourage governments from subverting good process, and provide a stronger safeguard against misuse of public money.![]()

Kate Griffiths, Deputy Program Director, Grattan Institute; Anika Stobart, Senior Associate, Grattan Institute, and Danielle Wood, Chief executive officer, Grattan Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Australians are tired of lies in political advertising. Here’s how it can be fixed

Our voting choices are only authentic if our decisions are informed by truthful information. That condition is now increasingly elusive.

In Australia, over two-thirds of adult news consumers report having seen media items they considered to be deceptive. This includes misleading commentary, doctored photographs and serious factual errors.

Political disinformation damages democracies. First, it manipulates voter preferences and distorts election results. This could be seen, for example, in the 2016 US presidential election and the Brexit referendum that same year.

It also polarises the electorate, damages trust in government and democratic institutions, and triggers civic withdrawal.

A further harm is that it raises the costs of voting. Electoral legitimacy requires that the costs of participation are not too high; false claims cause information costs to escalate because much more work is required to sift the facts from the false information.

A new and corrosive form of disinformation is political conspiracies of the “stolen elections” variety. This type delegitimises election processes, generates doubt about the authenticity of the declared result and undermines the authority of the electoral victor, who may subsequently experience problems in governing.

It can even lead to serious social conflict such as the storming of the US Capitol in January 2021.

A Global Problem

Election conspiracies also happen in Australia. During the 2022 federal election, the Australian Electoral Commission sought to counter a “dangerous” disinformation campaign waged by minor party candidates baselessly predicting a high degree of electoral fraud and interference with the results.

Examples of such baseless claims included:

the AEC is “aligned to the Liberal Party”

Australians who are not vaccinated will not be able to vote

blank ballots and “donkey votes” are counted for the incumbent.

The media landscape and its political economy have eroded both the media’s willingness to supply “truth” in political discourse, and the consumer’s demand for it.

Social media have decreased barriers to entry into the information marketplace. Meanwhile, many consumers seek out information that confirms their existing prejudices. In some countries there is now a lucrative market in the production of “fake news” solely to meet consumer demand.

To make matters worse, the ability of consumers to distinguish between authentic and fake news is much lower than they realise.

So, there are perverse – and arguably ineradicable – incentives within the information market to produce disinformation. The market is not just failing; it is the source of the problem.

This means disinformation has become what is known as a “collective action problem”. This happens when the actions of market actors create social costs that require state action to clean up or prevent.

Notably, 84% of Australians agree on this need and would like to see truth in political advertising laws in place.

But this is easier said than done. What if, for example, votes and entire elections really are being stolen? We must ensure solutions do not do more harm than good, inadvertently obstructing the free flow of reliable information that is the lifeblood of any democracy.

In our recent book, Max Douglass, Ravi Baltutis and I explore how this might be achieved federally. We propose a cautious approach that draws lessons from laws that have operated successfully in South Australia since 1985.

7 Ideas For Reform

To avoid chilling political speech – and thereby violating the implied freedom of political communication under the Australian Constitution – truth in political advertising laws will only target identifiable political actors who are authors or authorisers of the material in question. Publishers are therefore exempt, for now at least.

Only false statements of fact (rather than opinion) will be subject to the law, as per the provisions under section 113 in SA.

To deter vexatious and trivial complaints, the legislation should be limited to false statements that could affect an election outcome to a “material extent”.

Laws should cover the entire period between elections, to take in preference allocations.

Penalties – which apply only to those who refuse to take down offending material – should be high enough to deter wrongdoing. However, because some political actors will cynically treat the penalty as a routine expense to gain a political advantage, we propose an additional penalty that bars the candidate from standing for one election cycle, as is the case under UK law. This is hardly controversial since section 386 of Australia’s Electoral Act 1918 already disqualifies those who have committed electoral offences such as bribery, undue influence, and interference with political liberty.

Regulators should be properly resourced.

Electoral candidates could be asked to sign a declaration that they have read and understood what the legislation requires of them.

All of this is feasible, as the South Australian example has shown.![]()

Lisa Hill, Professor of Politics, University of Adelaide

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.