September 19 - October 2, 2021: Issue 511

Data From 29,798 Clean-Ups Around The World Uncovers Some Of The Worst Litter Hotspots + Australia Signs Pacific Regional Declaration On The Prevention Of Marine Litter And Plastic Pollution And Its Impacts

Addressing the international Ministerial Conference on Marine Litter and Plastic Pollution last week Minister Ley endorsed its Ministerial Statement calling for an international global agreement and yesterday endorsed the Pacific Regional Declaration on the Prevention of Marine Litter and Plastic Pollution and its Impacts.

“The Ministerial Conference Statement calls for clear and common objectives and actions to address the negative impacts of plastics along its life cycle, and Australia is already playing a lead role through our ban on waste plastic exports and our National Plastics Plan,” Minister Ley said.

“The 30th Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP) Environment Ministers’ High-Level Talanoa has sent a strong unified message about the importance of this issue to the region as well its support for a new global agreement.

“Ensuring our shared oceans are clean and healthy is both a national and regional responsibility for Australia as we face an international tide of eleven million tonnes of plastic entering the world’s oceans each year.

“We need an urgent global response to stem the flow of plastics into our oceans.

“I look forward to continuing to work collaboratively with our Pacific neighbours and the international community as we approach the United Nations Environment Assembly meeting in February 2022.”

Pacific leaders and high-level representatives put forth a Pacific Regional Declaration on the Prevention of Marine Litter and Plastic Pollution and its Impacts for voluntary endorsement during the Environmental Ministers’ High-Level Talanoa which took place last week at the conclusion of the 30th Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme’s (SPREP) Meeting of Officials.

“We, representatives of the people of the Pacific region and stewards of the world’s largest ocean, meeting at the Environment Ministers’ High Level Talanoa on 10 September 2021, are deeply concerned about the impacts of plastics and microplastics pollution on our region and that the current patchwork of international legal instruments is not sufficient to prevent the acceleration of these impacts,” the Declaration says.

The Leaders expressed their grave concern about the environmental, social, cultural, economic, human health and food security impacts of plastic pollution at each stage of its life cycle on the enjoyment of certain human rights for current and future generations.

Their concerns also extend to migratory marine species such as seabirds, marine turtles and whales as they are especially vulnerable to the impacts of marine plastics through entanglement and ingestion of plastic and reaffirming these species as important cultural icons for Pacific peoples.

“Marine litter and plastic pollution impacts continues to be of grave concern to the Blue Pacific,” said the Honourable Ulu o Tokelau, Faipule Kelihiano Kalolo, Chair of the Environment Ministers’ High-Level Talanoa.

“Notwithstanding that Pacific island countries contribute as little as 1.3% of global plastic pollution, we are grossly and disproportionately affected by its impacts.”

“The Pacific island region continues its leadership on this issue at home and abroad and call for a new binding global agreement on the prevention and reduction of new plastics and management of plastic pollution already in our environment,” he added.

The leaders and high-level representatives declared that they strongly support and urge all United Nations Member States at the Fifth Session of the United Nations Environment Assembly to support the establishment of an intergovernmental Negotiating Committee to negotiate a new binding global agreement covering the whole life cycle of plastics.

They also called for a new binding global agreement on the prevention and reduction of new marine litter and plastic pollution, as well as for future discussions on this agreement to consider the need for financial and technical support mechanisms to adapt international science and best practice to the challenges specific to the Pacific region.

The international community was also called upon to take urgent and immediate action to help the Pacific protect its region and peoples from further marine litter and plastic pollution impacts that threaten their marine ecosystems, marine species, food security and health.

The need for accessible information, support to scientific research on plastics, and plastic pollution data collection was also emphasised, as well as the development of marine litter and plastic pollution prevention best practice to inform robust, evidence-based and coherent policy.

The Declaration stressed the importance of incorporating Indigenous and Traditional Knowledge Systems, Practices, and Innovations as appropriate, together with their free prior and informed consent that have evolved through generations into nature-based solutions for the sustainable conservation of ecosystems as an integral part of the solution to the plastic pollution crisis.

The Ministerial Statement is available at ministerialconferenceonmarinelitter.com/ENDORSEMENTS and the Pacific Regional Declaration is available at www.sprep.org

Socioeconomic Factors Influence Land And Seafloor Pollution

The announcement precedes a study published Thursday September 16 that used large-scale citizen science data sets to show that socioeconomic factors like wealth and infrastructure combine with geography to influence what, where, and how much pollution is found on land, along waterways and on the seafloor.

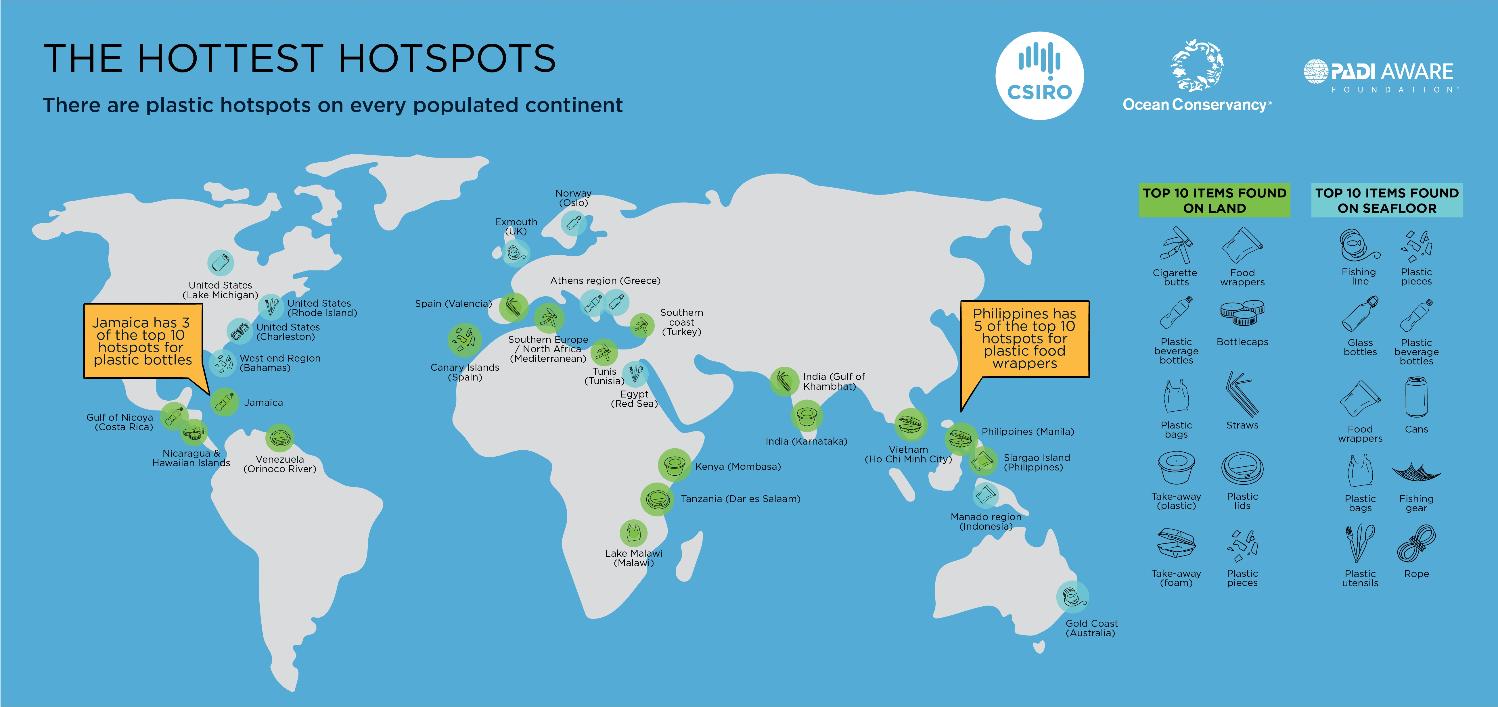

The research, ''Socioeconomics effects on global hotspots of common debris items on land and the seafloor'' was conducted by scientists at CSIRO, Australia’s national science agency; Ocean Conservancy, a U.S.-based advocacy non-profit; and the PADI AWARE Foundation, a non-profit public charity that drives global ocean conservation through local action.

In the first global analysis of its kind, the research team used comprehensive data obtained from 22,508 land-based cleanups as part of Ocean Conservancy’s International Coastal Cleanup across 118 countries (2011-2017) and 7,290 seafloor cleanups conducted through the PADI AWARE Foundation’s Dive Against Debris program in 116 countries (2011-2018).

CSIRO Senior Research Scientist and study leader Dr Denise Hardesty said the total amount of plastic pollution was higher where there was more built infrastructure, such as near cities. Less pollution was found in areas with higher national wealth.

“Pollution hotspots were found in every inhabited continent on Earth, not just in those places that have previously been identified as the biggest polluters,” Dr Hardesty said.

Hotspots of individual litter items, such as cigarette butts or food wrappers, were differentially driven by socioeconomic factors. For example, a positive correlation between cigarette butts and national wealth was found.

The study found that where local population increases, single use-packaging such as takeaway food and beverage containers also increase.

“Hotspots of plastic pollution also reflect the patterns of local deposition, waste management and accumulation. By identifying these locations using real data, local decision makers can assess opportunities on where and how to implement effective policies to reduce plastic in the environment,” Dr Hardesty said.

“Given the sheer volume of single-use packaging items recorded, changing the way we use and dispose of these items will likely substantially reduce the amount of litter found on land, in our waterways, and on the bottom of the ocean.”

Single-use plastics formed the majority of litter in this study. And in general, litter hotspots were associated with socioeconomic factors such as a concentration of built infrastructure, less national wealth, and a high level of lighting at night.

Our insights reveal the complex patterns driving coastal pollution, and suggest there is no “one size fits all” solution to cleaning up the world’s oceans. In fact, the best solution is to stop the waste problem long before it reaches the sea.''

However, not all litter items followed this pattern. For example, cigarette butts followed a regional pattern and were more common in Southern Europe and North Africa.

Fishing line was most abundant in wealthier countries where recreational fishing is a popular pastime. Hotspots included Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States.

Clusters of hotspots were often associated with partially enclosed bays, seas and lakes. These included areas such as the Mediterranean Sea, the Bay of Bengal, the South China and Philippine seas, the Gulf of Mexico, the Caribbean Sea, Lake Malawi and the Great Lakes of North America.

Plastic accumulation in these areas is likely due to factors such as high local littering combined with relatively contained bodies of water.

Plastic bottle hotspots were more common in tropical countries such as Costa Rica and Jamaica, among others. Plastic food wrappers were abundant in the island nations of Southeast Asia, particularly around Indonesia and the Philippines.

Surfrider Northern Beaches members doing a cleanup on Avalon Beach during the launch of Avalon Boomerang Bags, June 25th, 2016. AJG photo

Ultimately, the study reveals the diversity and complexity of the plastic pollution issue. The Authors hope it helps governments make waste policy decisions based on sound scientific evidence.

The findings suggest programs to tackle ocean litter should be rolled out at the grassroots level, or within one part of a country, as well as nationally.

In Australia, for example, Zoos Victoria’s Seal The Loop program aims to tackle localised fishing line waste at locations where the pastime is common. The program includes fishing line bins placed on piers and at boat ramps to encourage responsible waste disposal.

And in Malawi and 15 other countries in southern Africa, national bans on plastic bags target this locally problematic item.

The analysis shows much non-degradable waste found in the environment comes from pre-packaged food and beverages. So regulations specifically addressing this type of packaging can be useful.

In Australia, for example, Hobart is aiming to become the first Australian city to ban single-use plastic takeaway food packaging, as part of an ambitious goal of zero-waste to landfill by 2030.

Other strategies known to change litter behaviour include recycling incentives such as container deposit schemes, particularly in lower socioeconomic areas where littering is highest, as well as education campaigns. And levies on plastic items could also help stop litter entering the environment.

Chief Scientist at Ocean Conservancy, Dr George Leonard, said that the research demonstrated the global and heterogeneous nature of plastic pollution.

“Our research highlights the need for local policies and actions targeted to reduce plastic pollution, before it gets into the environment,” said Dr Leonard.

“Our study makes a strong case that beach and underwater cleanups provide critical, complementary data about the extent of plastic pollution in the environment,” said Dr Leonard.

Policy Lead for PADI AWARE Mr. Ian Campbell said the research demonstrated the critical need for empirical debris data from both land and seafloor surveys - and the importance of global datasets and large-scale citizen science projects.

“Litter that is found on land is not a reliable indicator for seafloor debris and vice versa, as different factors influence where and what types of debris are found on land and on the seafloor, although some items are common to both,” Mr. Campbell said.

“We found that some seafloor debris hotspots were associated with partially landlocked seas.”

Dr Hardesty said the research highlighted the valuable role that citizen science can have in providing scientifically robust data with real management and policy implications.

“This research could not have been done without the information collected by hundreds of thousands of citizen scientists conducting tens of thousands of cleanups world-wide,” Dr Hardesty said.

Plastic pollution findings:

- Contrary to some prevailing messaging about plastic pollution being a problem for the global south, plastic pollution hotspots are everywhere.

- The 10 most abundant items on land (in order ranked 1-10) included cigarette butts, food wrappers, plastic beverage bottles, plastic bottle caps, plastic bags, plastic straws, plastic take-away containers, plastic lids, and foam take-away containers and plastic pieces (fragments).

- The ten most common items found on the seafloor included (in order from 1-10) fishing line, plastic pieces, glass bottles, plastic beverage bottles, food wrappers, metal cans, plastic bags, fishing gear, plastic cutlery, and rope.

- Plastic beverage bottles were common in tropical countries, like Jamaica and Costa Rica.

- Plastic food wrappers were abundant in Southeast Asia, particularly around the Philippines and Indonesia

- Mass transit hubs, like train stations, are often hubs for single-use food and beverage packaging, but not items with recycling value.

- Cigarette butts were commonly found in South Europe and North Africa.

- Hotspots for fishing line occurred in Australia, UK and USA, where recreational fishing is a common pastime.

This research supports CSIRO's developing Ending Plastic Waste mission in development to achieve an 80 per cent reduction of plastic pollution entering the Australian environment by 2030.

The work follows on from years of research completed by CSIRO and years of plastic cleanups done locally by organisations such as Living Ocean, Boomerang Bags Avalon, The Green Team, The Northern Beaches Cleanup Crew and Surfrider Northern Beaches.

Ocean Conservationists Welcome Australia’s Support For Global Plastics Treaty

What Is The 'Global Plastics Treaty'?

- There is no clear global ambition or target

- No common obligation for nations to develop action plans

- No agreed standards for monitoring and reporting of plastics discharge into the sea

- No standardised review of the effectiveness of different pollution reduction measures

- No specialised scientific body with a mandate to assess the global problem and give guidance to decision makers

- Global targets with deadlines for reducing plastic and cleaning up our oceans, with all nations working together to eliminate unnecessary or dangerous plastics and ensure all plastic is reused, recycled or composted in practice. This could include things like an international ban on dumping plastic in rivers and waterways, and global bans on plastics like bags and straws that are a high risk for ocean wildlife.

- Monitoring and reporting on plastics in the natural environment, with nations required to report on their efforts to cut plastic. Advocates are also calling for a specialised international scientific body with a mandate to investigate and track the scale and sources of plastic pollution, providing world class scientific knowledge for effective policy making.

- Financial and technical support, with a dedicated global body providing financial support and technical expertise for countries with limited capacity. This would be critical for helping badly affected nations at the edges of the worst plastic hotspots like the Great Pacific Garbage patch, many of whom lack the infrastructure and resources to deal with the waves of plastic washing up on their shores.

- Pew Charitable Trusts and Systemiq. (2020). Breaking the Plastic Wave.