August 8 - 14, 2021: Issue 505

Bert Brownlie

Our community has recently lost this very popular WWI Veteran, known for his kind nature, brilliant smile, respect for those who have served our country and for his own efforts on our behalf.

Bert passed away on July 30th, 2021. He was the beloved husband of wife Dawn, father to daughter Kim and much loved uncle of extended family members.

Next Sunday, August 15th 2021, is Victory in the Pacific Day. Victory in the Pacific Day marks Japan's unconditional surrender to the Allies after more than 3 years of war on August 15th 1945. It's a time for us to reflect on the important role that Australians played to end the war in the Pacific region.

Almost 40,000 Australian gave their lives during this war. Over 17,000 of them lost their lives while fighting in the war against Japan, some 8000 of whom died in Japanese captivity.

Every family and every generation has a relative and story connected to the defence of our homeland during these years.

Although local Commemorative services to honour those who defended Australia during this conflict will be unable to be held this year, in 2020 Pittwater Online News was privileged to speak with Pittwater RSL Sub-Branch member Bert about his service as a Flight Mechanic with the R.A.A.F. for the B24 Liberators and life in the Warriewood valley afterwards.

His is a distinctly Australian and Pacific story.

Herbert 'Bert' Victor Collins Brownlie was 95 years young on November 11th 2020, and although born in Scotland, came here when still a toddler and considers himself a real Aussie. His father George served in WWI and became a member of the Willoughby Park stabled Light Horse Division, 18th Australian Infantry Regiment, "D" Company (part), after moving to Sydney.

Bert himself served in WWII as a Flight Mechanic with the R.A.A.F. and will lay a wreath on behalf of the Pittwater RSL Sub-Branch this Remembrance Day, Wednesday November 11th 2020.

Mr. Brownlie had undertaken this solemn tribute as a member of the Pittwater RSL Sub-Branch in previous years as well.

Photo by Michael Mannington, Community Photography

The same day as Bert's birthday, Remembrance Day Commemorative Services were held in our area, smaller than in previous years but still proceeding to honour those who have served and those who serve still, and as a means for those of us who still miss people now gone to remember them, as we do on every other day, but also to be able to honour their service alongside those who lost their lives in conflicts.

This week Bert shares a little of his own story from WWII.

Where and when were you born?

In Glasgow, Scotland on the Clyde bank, on 11th of November 1925. We moved to Australia when I was about one and a half. I’m a real Aussie really.

Where did you grow up?

Willoughby – I went to Willoughby Public School and then I went to Crows Nest Technical College. There I was studying the ordinary stuff as well as Woodwork, Metalwork, anything to do with working with your hands.

When did you join the RAAF?

On the 7th of December, 1943, just after I’d turned 18. Mum and dad gave me permission to.

I was a Motor Mechanic, an apprentice, at Joe Leach’s at Crows Nest, and volunteered for the RAAF because I wanted to be a pilot, but, education wise, it couldn’t be done, so they trained me as a Flight Mechanic.

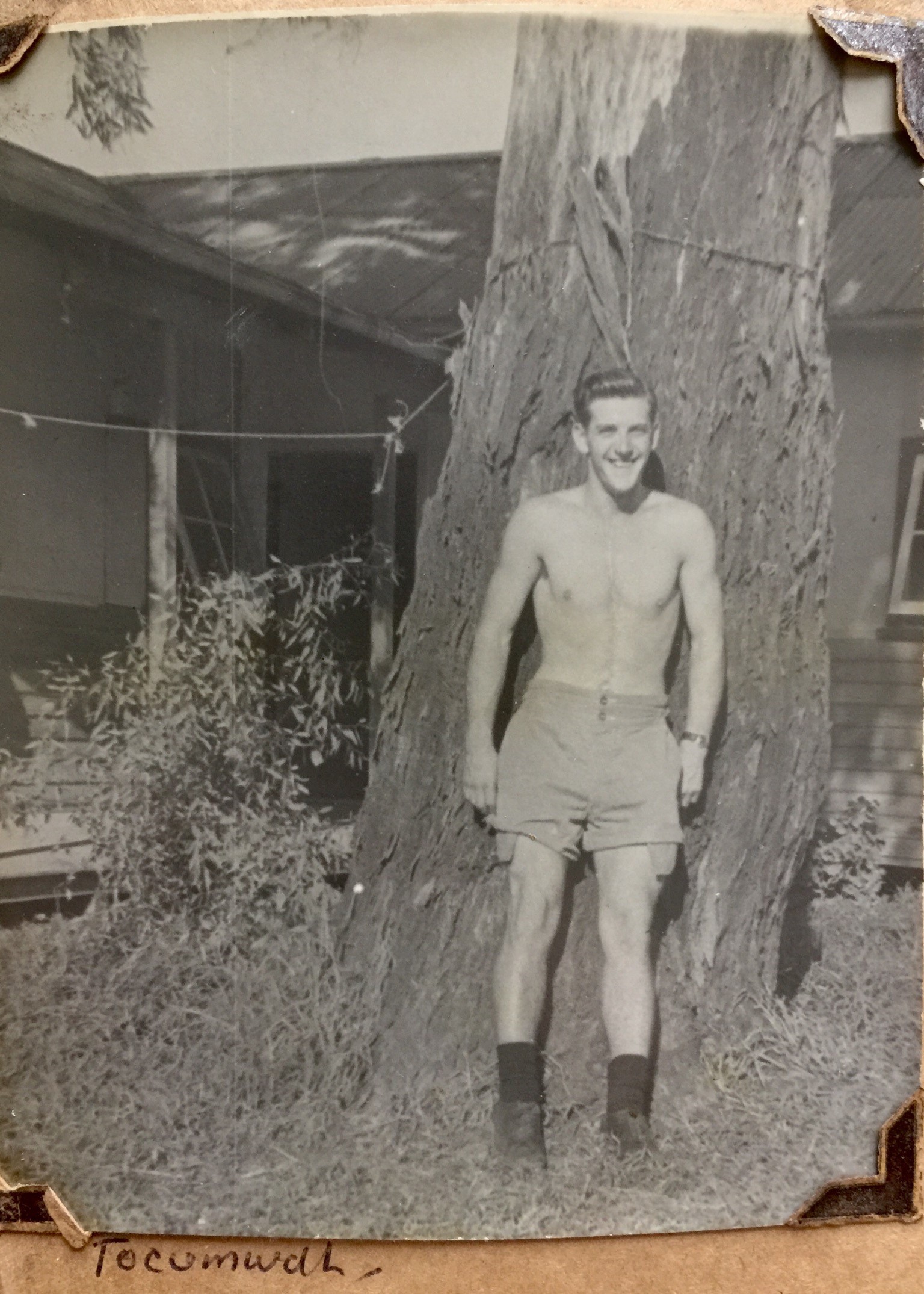

I was based at two fields, at Deniliquin, at 7 S.F.T.S. (Service Flying Training School), where we learned to work on all sorts of aircraft there, and then I was posted to Tocumwal NSW. My air mechanic training occurred in Adelaide and Melbourne and covered Aircraft systems, engines, air screws and parachutes. At Tocumwal I was part of the 7 O.T.U. (Operational Training Unit), where we worked on the Liberation bombers, the B-24’s.

Bert in uniform

Bert at Tocumwal

What did the servicing include?

You had to service the planes every 40 hours or also at 80 hours, they had different services and make sure the pilots were happy with it. This involved mainly working on the engines.

Which was the most difficult?

Well for me, being short, it was reaching things, but otherwise it was mechanical work which I found I could do. The Staff Sergeant mainly had me inspecting the work that other mechanics had done.

What was it like working on the B-24s?

These were quite big of course and one of the rules was that if you worked on a plane one of us had to go up in a test flight in it. You had Readers and they did all the map work and you had Armorers and they did all the gunnery work.

We went up in a test flight in a B-24 and when we were coming in to land the starboard wheels would not come down. So, there we were flying around, frightened as hell, and then the pilot said ‘try the manual pump, see if you can get it down that way’ – and see if we could get some fluid through and force the leg down. So we’re pumping, pumping, pumping and still wouldn’t work so he took the plane up to 5,000 feet and we thought, here we go, we’ll have to jump, and then there was this almighty BANG and then it finally let go from the wing and at first we thought it was tearing the plane apart but then we were all cheering because the darn thing finally came down.

Liberator B-24 bombers on the tarmac at Tocumwal

These things could happen on occasion.

The Gunnery, they used to clean the guns out and make sure they would fire alright and that the barrels were clean. They had the job of putting the oil around the cartridge and then flying up and making sure it was right around the cartridge – so that was part of what servicing was about too.

I was out on the tarmac servicing a plane and they said ‘how you going Shorty?’ and I said ‘alright’, and ‘geez I like these turrets’ – so they let me sit it in and asked ‘what do you think of that?’ – to which I replied ‘oh great’. Then they said, ‘well, pull the trigger’ which I did, and holy hell did that thing fire, they’d just cleaned it and it was so fast and so loud – frightened the hell out of me.

All the Armory in those planes was great – they had a front turret, they had a ball turret, which was on the bottom of the plane, and although I sat ion one I would not like to fly in one in a battle; you’re pretty exposed in that one, and they had a rear turret, and they had gunneries either side of the plane as well – so they had a good crew for these, for each plane.

Bert standing near air screw of Liberator at Tocumwal

Did you meet many Americans as a result of working on the B-24s?

Well, these were a Yankee plane and there were a few Yankee pilots there flying them but it was mainly a depot for training, so there were a lot of Aussies there, more Aussies than Yanks at that time.

I serviced Gypsy Moths, Wirraways, B-24s and P-40 Kittyhawks.

While at 7 OTU, General Macarthur inspected the base and decreed that we were to become a B-24 heavy Bomber base as the last line of defence after Townsville.

Some notable memories I have; we had a special base visit by Gracie Fields and I was dobbed in to sing for her, regrettably or thankfully, I only knew one song, “Annie Laurie”. Our first three B-24s to see action were set on fire by sabotage in their hangars. I helped service General Blamey’s B-24 which was fitted with arm chairs.

Did you see any of the Australian-built Spitfires?

Yes, I came across some of those at Ascotville in Melbourne when I was doing my training – I was there about 3 months. They were a beautiful plane.

Where were they flying to? The B-24’s were the long-range ones – do you know where they went?

They would fly up to Darwin and Townsville. From there they did all the air raids over Singapore and New Guinea. They were a tremendous plane for the Aussies and a boon for our defence then and many Aussies cam to know a lot about them of course.

When the war in Europe ended a B-24 Liberator Squadron flew over the Melbourne parade and I was lucky to be one of the airborne crew-members; what an amazing formation.

When were you discharged?

I was discharged at Bradfield Park on 12th of March 1946.

Why did they hang onto you for so long?

When we were finished we had the option of staying in there or getting discharged pretty much straight away. When the war was finished though we had a lot of work to do on the planes left here – they had to ‘mothballed’ in one way – we had to do various things, such as take the wheels off so no one could pinch them, that kind of thing. So all that kind of gear had to be taken off them and then what happened to them then I don’t know – the wreckers probably bought them for the steel or something.

Were you in Sydney when the Japanese midget submarines came into the Harbour?

Yes I was. My brother was on radar at North Head that night, he was in the plotting room, and he knew something had come in behind one of the ferries. He was on leave, and I was at home, and he said ‘ there’s something going on, I don’t know what it is but I spotted something’. At any rate, the police arrived at our house in Willoughby and said ‘you’ve got to come George, we need you.’

They took him back to North Head and he had to get to work and track these submarines down.

They knew something had come in in the wake of a ferry but they weren’t sure what it was.

Although we couldn’t hear the explosions you knew all about it with all the sirens going and the spotlights everywhere.

I hadn’t actually joined up when the subs came into the harbour – the people next door to me had two sons that were sailors and were on a boat that was sunk in the Coral Sea battle and they had just arrived home, so we were thinking ‘geez, that was close’ for them and it brought home that Australia was a target.

If they hadn’t have built the airstrip at Tocumwal, Townsville was looking pretty grim. When they had that Coral Sea battle it was this that actually saved Australia – if that didn’t go the way it did, Australia would have been in serious trouble. After that the position of Townsville became steady again, and, as General Macarthur said; ‘You blokes are doing a good job down there – and this is why I built that aerodrome at Tocumwal, in case Townsville fell.’

Were you frightened?

It was pretty frightening, yes. Darwin was horrific, the Coral Sea battle was terrible.

I remember I volunteered for a unit – up in New Guinea the Dutch had the Dutch Air Force and they were running out of ground staff. They asked the Australian government for mechanics. I volunteered to deploy and assist them, put my name down, did the medical, and thought ‘this is my trip overseas’. I was game as Ned Kelly then. This requirement was quashed by the Australian government, as was my chance to be posted overseas.

What did you do after it was all over Bert?

I didn’t know what to do. When I came back out I looked around and went back to my old job at Joe Leachs’ at Crows Nest, but he didn’t want to put me on permanently. I ended up moving around to a few jobs and ended up at the Daimler crowd at Hercules Motors and was servicing Daimler cars for them for around 15 years. when I left there I started working at local garages to be closer to home.

Home by then was Lane Cove – I’d met a nice girl there, in a cake shop. Her name was Dawn and we got married in 1951 and we’ve been married now for 69 years.

Unfortunately Dawn is in a care home at present and I’m here with my daughter Kim – a wonderful girl who has worked hard all her life too – and also looks after me. We now live at Warriewood – where I’ve been for 60+ years – we moved here about 61 or 62 years ago.

Bert and Dawn wedding photo

You must have seen Warriewood change from a place of glasshouses and rural paddocks to the residential area it is now?

I certainly have. It was a lovely place when we first came here but now they have old age homes everywhere and all these townhouses all over the place like you wouldn’t believe. The swampland used to have lots of ducks and other wild birds there – there was cattle and horses over the road from us. There was a riding school right near the main road, little kids used to stay there for the weekend and learn to ride. Then they sold all the property over there and made it into a big estate through one of these developers.

My little house doesn’t look as bright as it used to as a result.

Where did you go for a day out around here during those times?

A day out would be going to Narrabeen Lakes; we’d go prawning and fishing there. Our annual trip was to The Entrance – we’d go there for a couple of weeks, three families of us together; my sisters’ family and my mother in law and all the kids, Kimmy my daughter and all the nephews and nieces – it was beaut.

Did you ever catch eels or yabbies in the creeks at Warriewood?

Yes. We used to go down to Coal and Candle too – on the way there we’d pull into a creek there and get yabbies, big ones.

You would also have seen the changes in Pittwater RSL?

Yes – I joined the RSL when it was up at Coles street here – on the main road near the public school. They had a tin shed then, so a bit different from today.

Why was it so important, to you, to serve – to look after your community and look after your country, where did that come from?

It came from my father, George Brownlie, who was in the 1914-1918 war. He was a sergeant-major, and used to frighten the hell out of us with his voice.

When we were still small and living at Willoughby he was part of a unit there that was attached to the Light Horse. They were based up the top of Willoughby Park and had all the horses and stables up there.

They used to come down of a weekend and would go down High Street and along Mowbray Road, past our house, in all their livery and leather boots, my father among them. This used to make me feel like I want to be part of them, seeing that. Also knowing what he did during that war, that was a terrible war.

So I thought ‘I’d like to do something like that, to help.’ You didn’t do it just to big note yourself, and some of the people you met you just couldn’t get on with, it wasn’t all some make it out to be – it was challenging for every single person in individual ways – but there was this idea of ‘for King and country’ which we were brought up with at Willoughby school – you’d commence the day with saluting the flag and singing the National Anthem and this made you feel proud to be part of this country.

Bert in 2020 at Pittwater RSL Commemorative Service - Photo by Michael Mannington, Community Photography

What are your favourite places in Pittwater and why?

At the moment I’d say Pittwater RSL Club. Because, I don’t look for much, but I like to have a play on a poker machine and I like a couple of beers, and I like the company there.

What is your ‘motto for life’ or a favourite phrase you try to live by?

Don’t worry love.

I’d say this to Dawn all the time. You see, things happen, they always do, they always will – so don’t worry too much you will just make yourself and life miserable that way.

Bert in 2020 - Photo by Michael Mannington, Community Photography

Notes

BERT BROWNLIE - born 11 November 1925

Service No. 138575

Royal Australian Air Force - Leading Air Craftsman

7 S.F.T.S. (Service Flying Training School).

7 O.T.U. (Operational Training Unit)

1939-1945 War Medal

Australian Service Medal 1939-1945

GRACIE FIELDS: RAAF Plane Journey From Tocumwal

Gracie Fields arrived at Essendon airport shortly after 5pm yesterday in a RAAF plane from Tocumwal.

Very few of the general public knew when she was arriving, but this did not prevent the news getting round, and a fair number of the regular visitors to the airport on a Sunday afternoon sensed that something was doing, and waited to greet her warmly as her car left the drome for the city.

Miss Fields left Sydney yesterday morning for Tocumwal RAAF station, where she gave a concert to several thousand airmen. The concert went wonderfully well, Miss Fields singing about 15 songs from her extensive repertoire.

With Miss Fields on the plane were her husband, Monty Banks, Mr E. J. Tait. Miss Dorothy Stewart, a native of Heidelberg, who is visiting home for the first time for 10 years; Miss Beatrice Tange, solo pianist; Miss Peggy Shea, who sang at the Tocumwal concert; Mr Eric Fox, accompanist, who joined Miss Fields' party at Brisbane; and Flight-Sgt Victor Moore, baritone.

Miss Fields was met by Messrs Frank and John Tait and Mr Claude Kingston, general manager for J. and N. Tait. She stood for Press photographers, and then, as she was walking toward her car, she saw men of the RAAF stationed at Essendon and a few other servicemen grouped together ready to cheer her. She made straight for them, and beat them to the cheers by shaking hands with them and showing some boomerangs and other souvenirs which had been presented to her since her arrival in Australia.

VISITING HOME CITY

Miss Dorothy Stewart, who was born in Heidelberg, is visiting her home city as personal manager for Miss Fields and her Australian tour. She has made quite a name for herself on Broadway, and is American representative for J. and N. Tait. She was well known in Melbourne before she left for America for her songs at the piano. She is the com-poser of both words and music of "God Bless Australia," sung throughout Australia and the United States, from which half the money goes to the Red Cross. Her latest composi-tion is a rhumba, "Blue Velvet." She accompanied Miss Fields on her flight across the Pacific, which, she said, was a wonderful experience.

Miss D. Stewart. GRACIE FIELDS ARRIVES (1945, July 2). The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 - 1957), p. 3. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article973150

Australian Troops Save Life-And Wealth-In Battle Areas (1945, July 2). The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 - 1957), p. 9. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article973139

RAAF Station Tocumwal (35°48′S 145°34′E) was a major Royal Australian Air Force base during World War II. Located near the town of Tocumwal, New South Wales the base was established in early 1942 to provide a secure base for United States Army Air Forces heavy bomber units. While the USAAF does not appear to have used the base, it was heavily used by the RAAF and, from 1944, was home to the RAAF's heavy bomber support and operational conversion units including No. 7 Operational Training Unit.

While RAAF Station Tocumwal was closed following World War II the airfield remains in use and is a renowned gliding site.

200 houses from the base were relocated to Canberra in the 1940s to address a housing shortage. The vast majority were relocated to a small precinct in the suburb of O'Connor, and in 2004 were added to the ACT Heritage Register.

No. 7 Operational Training Unit RAAF (7OTU) was a Royal Australian Air Force heavy bomber training unit of World War II. 7OTU was formed on 12 February 1944 at RAAF Station Tocumwal in southern New South Wales to train RAAF B-24 Liberator crews. 7OTU was initially equipped with ex-USAAF B-24Ds but later received new B-24J/L/Ms. At full strength the unit was equipped with 54 B-24s and was responsible for training 28 crews per month. 7OTU was disbanded following the end of the war.

In 1944 one of the few verified instances of sabotage occurred at Tocumwal, when major sections of the wiring looms in 12 B-24s were cut and removed. This put the aircraft out of service for several months until the damage could be assessed, replacement looms fabricated in the USA, then installed by Consolidated technicians flown to Australia to do the work. The sabotage was believed to have been carried out by a Japanese cell that had been under cover in Australia since prior to the war, however no one was ever captured nor convicted of the act.

TOCUMWAL AIRFIELD DURING WW2- Previously known as "McIntyre Field" by the USAAF see: https://www.ozatwar.com/tocumwal.htm

The Tocumwal Historic Aerodrome Museum documents the history of and the importance of Mcintyre Airfield in Tocumwal, and also post war operations when over 700 aircraft were scrapped for aluminium. Later the airfield became a famed gliding destination.

Tocumwal is famous for many things - stunning beaches, the redgum forests on the outskirts, a fantastic golf course, the giant cod, glider and B24 replicas on poles, but Tocumwal is also famous for its role during WW2. The town was used as a major base by the US during the war effort, but then after the war ended, the area around the airfield became a massive aircraft graveyard and many hundreds of planes were chopped up, stripped and melted down.

You will find a wealth of information in the museum - stories, maps, photos, news articles and scale models.

Presentation can be arranged on request. Visit: https://www.visitnsw.com/destinations/country-nsw/the-murray/tocumwal/attractions/tocumwal-historic-aerodrome-museum

Our Biggest Airfield

The Story Of Tocumwal

By KEITH NEWMAN

NOT long after the Japanese entered the war and while they were still sweeping south in what seemed an irresistible advance, a group of airmen stood on a small rise near the Murray River, looked across a bare plain, and agreed, "This is it".

They were newly-arrived Americans, seeking a site for a base for heavy bombers. If the Japanese entered Australia and continued their drive south the base was to be an important factor in this country's last-ditch defence.

THAT was the genesis of what has become Australia's biggest airfield; a spreading pattern of runways, taxiways, roads, hangars, workshops and other buildings covering 25 square miles. It is at Tocumwal on the New South Wales side of the Murray, roughly midway between Corowa and Echuca. It has not been possible to tell Tocumwal's story in any detail before for security reasons.

The airfield was built by Australians to American specifications but the American fliers have long gone from Tocumwal. The battles of the Coral Sea and Midway and the tenacious work of Australian infantrymen in New Guinea changed the Pacific position so completely that the day arrived when according to the picturesque story that airmen tell, the chief or General MacArthur's air arm Brigadier-General Kenney came down to Tocumwal, looked around and drawled "Mighty fine base. Shift it 2,000 miles closer to the enemy".

How a new base was built 2,000 miles closer to the enemy is a dramatic engineering story that yet to be told. Tocumwal reverted to the RAAF which has built it into the continents leading training establishment. Where hundreds of airmen are being trained to fly the mighty four-motored Liberators, whose enormous range and great hitting power put these squadrons among the toughest things the Japanese have to face.

TOCUMWAL'S story must be told in two phases. How it was built and what is being done there now.

An Allied works Council Report describes Tocumwal as the most spectacular item in the whole programme.

When one realises that this mammoth undertaking was built from nothing to a useable air base within 14 weeks the claim does not appear exaggerated.

In the preliminary stage there was not even an Allied Works Council and the bulk of the engineering and constructional work was in fact carried out by four departments of the New South Wales Government ---Public Works Water Conservation and irrigation Commission, Main Roads and Railways.

The Allied Works Council came into being in February 1942 the month in which work began at Tocumwal and it eventually absorbed the functions of the other instrumentalities.

Organisation was enormous in such a rush job carried out on such a scale that it absorbed three months output of tar from the Broken Hill Pty Ltd.; for surfacing runways and roads.

Runways and taxiways for heavy bombers weighing tons have to be of great strength. More than 500,000 square yards of such surface was built as well as over 70 miles of roads and 250,000 cubic yards of open drains to keep the field serviceable in wet weather and more than 600 buildings.

At peak 2,700 workmen were engaged in 24-hour shifts. At night the plain was lurid with the glare and smoke from hundreds of flares.

Machinery drawn from a variety of sources was concentrated at Tocumwal.

Two huge dragline dredges each weighing 120 tons crawled 70 miles from Deniliquin under their own power. Because of their weight they avoided roads and bridges and as they came to a creek or irrigation channel they filled it with great bites of earth each of five tons, crossed over, dug out the crossing they had made and moved on to the next obstacle at one third of a mile an hour

It was a phase of engineering endeavour in which men and machines raced against time. The cost was around £3,000,000.

The second phase is also one of men and machines. But the machines now are engines of destruction with which the Japanese Empire is being broken down into it's original pieces. Tocumwal's important function is to teach Australian airmen how to use the £ 90,000 machines known as Liberators tor this purpose although the airfield is also a vast depot for the reception repair and maintenance of the big bombers.

Details of the strength or disposition of Liberator units actively engaged against the enemy are naturally secret but a glimpse of the increase in the RAAF'S striking power in recent years may be gained from the fact that Tocumwal has over 50 of these giant planes for training alone and that it turns out a batch of new crews every two months.

Liberators have played a big part in the war. Their range with full load of some 3,000 miles enabling them to patrol vast areas of ocean and to attack remote targets. They are peculiarly fitted to Pacific conditions.

Their crew may be as many as 12 according to range and nature of the mission of the moment.

Even more interesting than the machines at Tocumwal are the men, for there are few rookies there. Their two months course is conversion and operational and although youths in years, most of the trainees are veteran airman. The chief flying instructor is one of Australia's foremost combat airmen of this war. Wing-Commander A. L G Hubbard DSO DFC, who commanded famous "460" ---the first Australian squadron equipped with Lancasters which from its English base, has flown out to leave many grievous scars on Germany's face. He also served in North Africa.

MANY of his pupils have followed in his vapour trails and are equally decorated. Others wear ribbons earned on Coastal Command patrols during the Battle of the Atlantic or in other fields where they have helped to hammer contemporary history into the present satisfactory pattern.

The commanding officer of the training unit (No 7 OTU) is Group Captain A. A. Barlow who led some of the earliest bombing attacks against the Japanese from New Guinea. Station commander is Group Captain R. S. Brown A.F.C., a member of the Australian Flying Corps in the last war who commanded at Point Cook before going to Tocumwal. His son is a fighter pilot in Belgium.

Training routine at Tocumwal is built around 10-hour flights across country or far out to sea, during which practice bombings are carried out and mock battles -fought against packs of Kittyhawk fighters.

The mock battles are not devoid of excitement "You had better wear your chute" said the captain of a Liberator in which I flew on a recent training sortie. "These fighter pilots are pretty intrepid types and they come close at times" The advice seemed sound a little later when about 30 "intrepid types" beat up our formation of 20 Liberators.

JAPANESE pilots should not copy their tactics however. Liberators are heavily armed with 5 machine guns, which are effective up to 1,000 yards and any fighter weaving around or into a bomber formation could be cut to ribbons by a murderous cross-fire it the gunners were playing for keeps.

Several millions of pounds worth of aircraft was engaged in the mock battle. As its purpose was to teach some hundreds of our airmen to play for keeps & win it seems a worthwhile investment.

A batch of new crews is turned out every two months. Tocumwal has over 50 giant Liberators for training alone.

Our Biggest Airfield (1945, February 3). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 8. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article17944219

The Consolidated B-24 Liberator is an American heavy bomber, designed by Consolidated Aircraft of San Diego, California. It was known within the company as the Model 32, and some initial production aircraft were laid down as export models designated as various LB-30s, in the Land Bomber design category.

At its inception, the B-24 was a modern design featuring a highly efficient shoulder-mounted, high aspect ratio Davis wing. The wing gave the Liberator a high cruise speed, long range and the ability to carry a heavy bomb load. Early RAF Liberators were the first aircraft to cross the Atlantic Ocean as a matter of routine. In comparison with its contemporaries, the B-24 was relatively difficult to fly and had poor low-speed performance; it also had a lower ceiling and was less robust than the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress. While aircrews tended to prefer the B-17, General Staff favoured the B-24 and procured it in huge numbers for a wide variety of roles. At approximately 18,500 units – including 8,685 manufactured by Ford Motor Company – it holds records as the world's most produced bomber, heavy bomber, multi-engine aircraft, and American military aircraft in history.

The B-24 was used extensively in World War II. It served in every branch of the American armed forces as well as several Allied air forces and navies. It saw use in every theater of operations. Along with the B-17, the B-24 was the mainstay of the US strategic bombing campaign in the Western European theatre. Due to its range, it proved useful in bombing operations in the Pacific, including the bombing of Japan. Long-range anti-submarine Liberators played an instrumental role in closing the Mid-Atlantic gap in the Battle of the Atlantic.

Australian aircrew seconded to the Royal Air Force flew Liberators in all theatres of the war, including with RAF Coastal Command, in the Middle East, and with South East Asia Command, while some flew in South African Air Force squadrons. Liberators were introduced into service in the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) in 1944, after the American commander of the Far East Air Forces (FEAF), General George C. Kenney, suggested that seven heavy bomber squadrons be raised to supplement the efforts of American Liberator squadrons. The USAAF transferred some aircraft to the RAAF, while the remainder would be delivered from the USA under Lend-Lease. Some RAAF aircrew were given operational experience in Liberators while attached to USAAF squadrons. Seven flying squadrons, an operational training unit, and two special duties flights were equipped with the aircraft by the end of World War II in August 1945.

The RAAF Liberators saw service in the South West Pacific theatre of World War II. Flying mainly from bases in the Northern Territory, Queensland and Western Australia, aircraft conducted bombing raids against Japanese positions, ships and strategic targets in New Guinea, Borneo and the Netherlands East Indies. In addition, the small number of Liberators operated by No. 200 Flight played an important role in supporting covert operations conducted by the Allied Intelligence Bureau; and other Liberators were converted to VIP transports. A total of 287 B-24D, B-24J, B-24L and B-24M aircraft were supplied to the RAAF, of which 33 were lost in action or accidents, with more than 200 Australians killed. Following the Japanese surrender the RAAF's Liberators participated in flying former prisoners of war and other personnel back to Australia. Liberators remained in service until 1948, when they were replaced by Avro Lincolns.

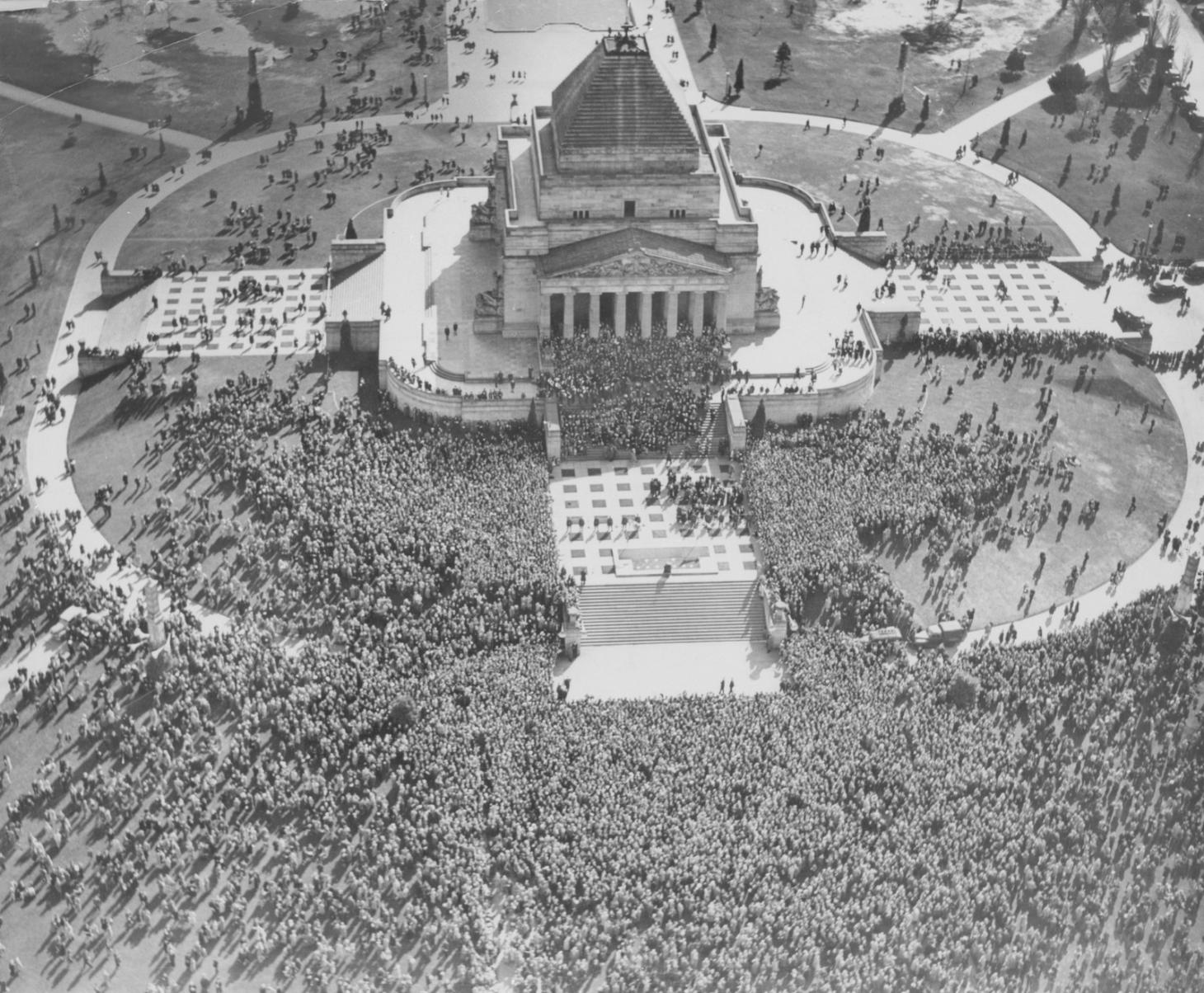

GAY STREET SCENES IN MELBOURNE

Crowds Cheerful but Very Orderly

The V-E holiday was received soberly, almost devoutly in Melbourne, after a warm sun had dawned upon a grateful City of Empire.

Slowly the streets began to fill as people passed through the city, bound either to the Shrine service, churches or the public parks, reaching , a climax at 5 p.m., when six policemen were on duty at Collins-Swanston streets intersection. Chinatown had its own proud display of appreciation of victory in Europe — the national flag of China, which flew from many homes In Little Bourke-street— the flag which has flown these long years since 1937 in the- face of the Japanese. In the suburbs, too, there was much color and gaiety in home decorations. City strollers found much of interest' in the windows of beflagged shops and stores-windows crammed with appreciations to the Allied leaders, one in particular taking the eye, of the simple Dove of Peace. Khaki and -green, navy, blue and drabs. This was the maelstrom which' flowed past the background of the flags and bunting, a solemn reminder to celebrating families of another peace, yet to be achieved. There were not as many people in the city as on Anzac day but nevertheless the innate desire for giving vent to pent-up feelings of freedom and joy and love came from many. Crocodiles were formed and marched through the streets. Groups walked round The Block singing. And the songs they sang were not the songs of warriors— they were the songs of the human heart, home again where it belonged, In a land of peace.

At 3 p.m. the planes came— 15 fighters flying in Victory V formation. Thousands of happy faces turned skyward in mute salute — not just of the planes above in the Melbourne sky, but of the planes which had flown through other skies, by day and by night, and there were memories written on the upturned faces, and some were sad.

Kerbstone sellers of pennants and horns were in continuous business throughout the day. But they, were the only sign of commercial life. Few cafes were available to the city crowds, who, when first finding this situation, turned to more rejoicing on the celebration — which is the greatest food of all — Freedom.

Police had a quiet day. Early in the morning - three people had been put in the City Watch House on a charge of unlawful possession. They were caught with 8-feet long Australian, flags— openly removed from some decorated building.. "It's V-E day," they said by way of explanation.

Railway traffic both to the suburbs and hills was heavy. On some stations, however, there were deeper feelings than celebration. From Spencer-street' station a group of young Australian sailors was farewelled by mothers and fathers.

Young People's Night .. .

Melbourne belonged to the young people on V-E night, as singing youth paraded the streets in small parties, or congregated in groups as corners. The most popular song was Lili Marlene, with 'Keep the Home Fires Burning', 'Tipperary' and a wistful perhaps even hopeful 'Roll Out the Barrel,' reminding them that even with European struggles concluded some peace-time restrictions would still remain. The fire brigades reported numerous alarms, due to suburban bonfires lighting up the sky, as well, as many false alarms, one being to a large city building at the corner of Flinders-lane and Swanston-street. . With all city amusement places closed, it proved a diversion to the aimless crowd which gathered to cheer the firemen as they tried to break into the doorway, then stayed to sing in the largest and most sustained group In the city. Police were tolerant, and interfered only when necessary. Two wireless patrols were called to Bourke-street, where youths were Interfering' with flag, decorations. Repressed feelings against controls may have been aired when traffic signs, "No parking." "Taxi only" and many others were lowered to the ground. Waste bins were removed; mostly a few yards from their stands, but altogether few acts of vandalism were noticed.

Opportunities for night displays in lighted windows were missed by most stores. Those with pictures of Allied leaders attracted great crowds. And there in a Bourke-street department store, dwarfing, pictures of generals, politicians and leaders, a bronze British lion gazed majestically.... GAY STREET SCENES IN MELBOURNE (1945, May 10). The Age (Melbourne, Vic. : 1854 - 1954), p. 5. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article204022718