May 31 - June 6, 2015: Issue 216

Tim Hixson

Tim Hixson

www.timhixsonphotography.com.au

Spending a little time with photographer Tim Hixson is an amazing experience; like a wonderful tutorial on what real photography is. Humble, focused on the process and how much that determines the outcome, citing the paths trodden and made by those who went before him, finding he’s still learning himself and happy that he is, this is what makes a great teacher.

You also sense a bit of every road he has travelled, and envision a keen eye that is looking around him, out in the dawn, embraced by everything there, one ear listening to what is on this sphere, the other hearkening to every other, and still prepared to examine the vision afterwards, to know he was not just walking through Byron Bay fields filled with early frogsong while gold and pink tainted the horizons, but that there would have been dew in those lush fields too, that wet feet and wet path made have established some moment beyond words. And he is quietly smiling in this vision, bright eyed himself.

Mr. Hixson is a saltwater man as well, fleet through water to championship level and then immersed in the ocean outside pool rims, another track wends, allowing many to be in the sea even when far from it through images that are visions, the memories that stick from one moment.

The great grandson of Captain Francis Hixson, who was surveyor for the charts of these waters, and grandson of Edward Manwell, the Captain’s second son and a surveyor himself of railways when they were beginning in Australia, it should come as no surprise that his art and his own living has a touch of surveyor throughout his ways and that he has added to and given much to one of the world’s most loved art forms.

When and where were you born?

I was born in Adelaide in 1950.

Did you grow up there?

I was there for the first couple of years of my life and then we moved to Lane Cove and then Collaroy. Collaroy is the first place I really remember.

I remember the beach and running down Collaroy street. We lived in a four storey house which was my auntie’s house and this was where the squash courts were, then later became units. I’d run up to the top floor of this home and look out, you could see the ocean. I’d run downstairs, across Pittwater road, no cars then, and onto the beach.

It was a paradise for kids because there was never a big swell there and we had all of that wonderful area to play in; the pool and around the rocks to Long Reef, you could fish and explore while playing, it as just fantastic.

I had a number of years there and then we moved to West Pymble and I’d hitchhike down to the beach every weekend.

I was in Collaroy Surf Club, joining when I was 16. I was there for a couple of years. We had a very good competition group at that time, with my lifelong friend Brook Worthington. I competed for one season before I went to America and was fortunate enough to win a couple of golds and a bronze at the Australian Championships.

Prior to this time I injured my leg playing rugby at West Pymble and was incapacitated for a year and so took up bike riding and swimming, which led to my joining Collaroy Surf Club and the swimming got me a scholarship to university in America – Southern Illinois.

They had a very good photographic Department.

I hitchhiked to California from Illinois on Route 66 – the university was about mid-Illinois, about a third of the way across America. I trained for the Summer Phillips 66 Club, which was the top swim club then. For the trip over I had bought an Instamatic camera and taken some photos.

When I returned to university at the end of Summer I thought I’d take a course and figure out how to do this; there was more in the pictures than I thought I’d taken. You then get into the magic of the whole process – the dark room, the chemicals and light, and then you get hooked and in this way I not only found my Major, which was in Cinema and Photography but a major interest.

Southern Illinois was a terrific school for this, there were some very fine teachers and it had very strong Design Department. While I was there the Emeritus Professor of this Department was Buckminster Fuller.

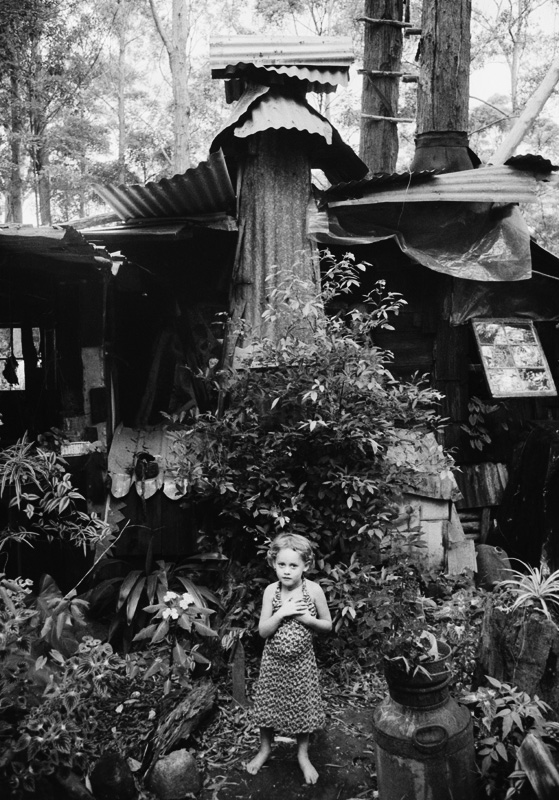

This paid dividends for me later on as well. Two years ago I had a commission from Lismore Gallery to photograph homes that would enable them to celebrate the 40th Anniversary of the Aquarius Festival – this entailed photographing five exemplary houses which were still lived in by their owner-builders.

So from Murwillumbah to Lismore, Nimbin and that area were these five homes and he five owners said yes, they’d like to be a part of this exhibition called Not Quite Square.

There was a dome amongst the choices at Tuntable Falls which was my ticket in as Geodesic Domes were an invention of Buckminster Fuller, and although people in this area don’t like a lot of media coverage due to the adverse affects from a sensationalist focus on criticising the drug aspects of some areas, this exhibition was not about that. This was about the quiet achievers that survived through the Aquarius Festival and built a life for themselves and their families and built these sculpturally beautiful homes, homes which withstand cyclones, trees falling, floods and the time itself.

These are beautiful homes, magnificent in fact. They are all hand made and as such are living sculptures.

I lived in Byron Bay during the mid 1970’s, returning to live there from the States after I’d finished my degree at university. I would go into Mullumbimby and other areas and take photographs for myself, to develop my personal photography, and for others.

What was it like studying in America?

It was a very interesting and in some ways a very difficult time. It was the time of the Kent State riots and the big protest against the war in Vietnam and our university closed down during a protest at the university. After it reopened it had all changed – there was quite a big difference between the counter culture and the existing culture. It was a massive time to be in America and I was lucky enough to be there then.

Was the university more conservative when it reopened?

No, quite the opposite. America is great in this way. America might seem like a place where you can experience the best and the worst, as it is everywhere, but in America even though it seems a conservative bastion, there is underlying liberalism. I was in a country town with a population of 30 thousand people and around 25 thousand students, and we lived out in the country, on grounds there were fought over between north and south during the civil war, so you would think this would be a very conservative area, and it is, but it’s also very accepting and it works – this new meeting old over and over.

It was a beautiful place, rural, I loved it. You could take off from there to anywhere else in America.

Where we were was at the end point of where the glaciers brought all the top soil down from Canada and spread it all across the Midwest – where this finished was all rubble. If you drive up to Chicago from southern Illinois you see the blackest soil you could imagine black soil to be and metres deep – so it grows everything, it’s the breadbasket of America, and where it finishes is southern Illinois and the university, which is positioned between the Mississippi and the Ohio rivers. It was a wild landscape but really beautiful – I’d keep finding these great places to explore and photograph and the university was like an oasis amongst this. I loved it – I was very lucky to have that opportunity.

What would you nominate as those events or experiences that stand out starkest from your time there or have informed or affected you afterwards?

The photography would be important, discovering that.

Photography doesn’t have quite the same relevance here. In America photography is a really valued art form and American photographers considered great artists in their country.

It falls away from this a bit here, we tend to follow the latest technology rather than study the Masters. But in America you could actually study the Masters in Photography so that set me up to appreciate where it came from, where photography itself came from. This is particularly relevant now because of the digital age where some people may think photography started with the first digital camera when actually it didn’t.

This is an art form that’s nearly two hundred years old now, but, it has never stopped changing. You have to accept that it will always change, for better or worse, it progresses.

At present it seems more concerned with the latest software and the technology side of it rather than paying homage to where to came from. It will, no doubt, go back to respect that but at the moment it hasn’t got time.

Being in America when that huge social change was occurring would be another – the thing that got me there is that people can make a difference. In other words, if the argument is strong enough, and popular enough, it will change the rest of the world.

The exhibition, called ‘Not Quite Square’ at Lismore, which also went to Sydney University too, is a great example of this. It shows that people living up the coast and elsewhere, who are the people who started or revived things like solar energy, subsistence living, orientating a house to make the most of the environment it is in, recycling waste products back into the earth, wholistic thinking, growing your own food, taking care of Nature and a whole gamut of attitudes are now incorporated into what we do – now you cannot build a new house without incorporating a water tank for example. These houses were built to orientate them to their environments, and this was 40 years ago and it has taken that long for it to come back.

Main arm 1 from NOT QUITE SQUARE

Monks from NOT QUITE SQUARE

You can see this reflected around Avalon with the care and respect for the trees, beaches, young people raising bees, riding bikes, people growing things and living a healthy lifestyle and enjoying Nature. This seems a more meaningful way to live and I try to incorporate some of this in my photography.

And Third?

Wynn Bullock an American Photographer who was a bit of a genius. He assisted Man Ray in Paris in the early 1920’s, had two photographic patents granted, was in the ‘Family of Man’ exhibition that toured Australia in the 50’s, explored unique photographic processes and made searching and intriguing images.

What happened between when you returned to Australia and now?

I lived in Byron – it was so idyllic, we lived in a farmhouse on a hundred acres, on a ridge overlooking the beach near Broken Head - we paid four dollars rent a week. I had a dark room, a room to shoot in. I received a Visual Arts grant and was doing my art. I married my first wife Joanne and we thought we were too young to retire so we came down to Sydney in 1977 and moved to Watkins road Avalon and I lived there for 30 +years. We had two wonderful children, Katie and Alex. I got a job in a dark room, printing, and was getting good at printing but then did it commercially and learnt how to really print.

I didn’t want to be a commercial photographer, I wanted to do my own thing, but I had to make a living, I had a house and children and all that and so started to shoot commercially. I did that for a long time.

For a while I was so committed to it that I’d print all day or do the commercial shoots and then at night I’d go home to my own dark room and print at night. You had to live and breathe it, it’s just what you did if you had that passion – you would have to disengage from the commercial stuff and get into the creative.

At the same, you’re learning from both, they inform each other.

After doing that for a while I progressed to sharing a studio with a couple of other photographers in McMahons Point and worked out of there for years. I was one of those guys that left home at quarter past seven in the morning to beat the traffic. Nowadays that has become a quarter to six.

So I’d get to work and do my thing, or give myself a treat and go for a surf first and then head in.

Around 1990 I separated from Joanne and lived with Katie and Alex at Watkins Road. This made for a huge change and I worked hard at providing for a 10 and 13 year old.

A few years later I met and married beautiful Bronwyn and she and her daughter Lauren moved in with us. So our blended family became a loving and close unit. Bronwyn’s strength and generosity allowed (and gently pushed) me to take up personal photography again and this led to a lot of ideas being executed.

These days I’m semi-retired but still shoot personal work and some commercial photography, mostly new cars.

I have discovered how good yoga is for my wellbeing and take classes with Bronnie Hixson at the Surf Club, called ‘Men on the Mat’. We have a 2 year old granddaughter, Emma, and love and enjoy the company of our friends and family.

What was your first exhibition?

I had a few in America while I was a student. Then when I got back to Australia I had a few where I sent the work over to there. Then, because I had family commitments and work to do, I let it slide for a while before coming back into it.

There as a group called the ACMP, a professional photographers association, and they had the ACMP Awards and produced these beautiful books sponsored by Fuji. I began to enter these competitions and that became an outlet for my personal wok.

Then Sandra Byron, who was a Curator and Gallery owner in Sydney asked me to join here and I was able to exhibit with her for quite a few years. That was 15-20 years ago.

Then it went on from there.

What is your latest exhibition?

As part of the Head On Photo Festival. The Head On Festival is the second biggest in the world and is based in Sydney during the month of May.

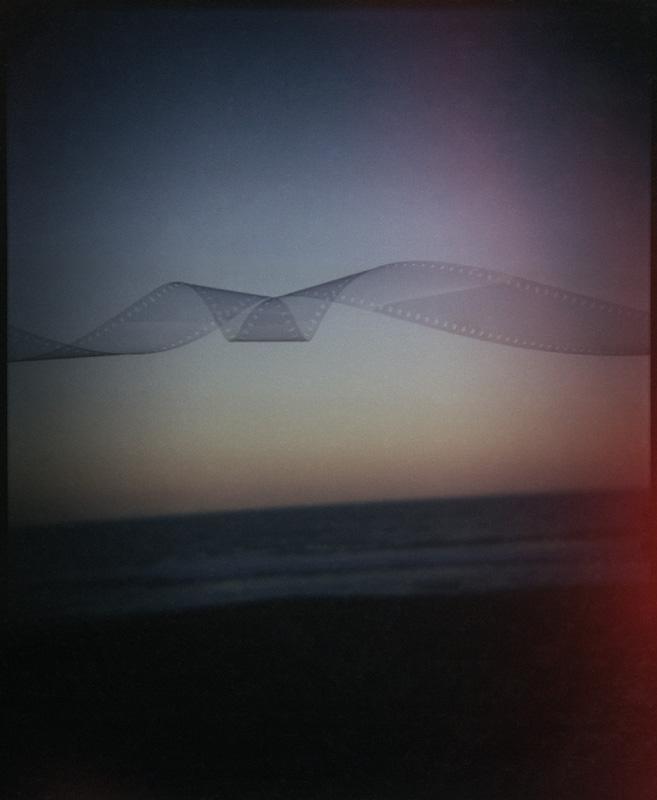

This is a group show by a group called the Ludlites: www.ludlites.com who all use these plastic cameras. I’ve been using these since I was a student in America. Those cameras see the world more as I do, they allow for imperfection, they make mistakes and allow for that interpretation to come through. The digital cameras don’t make mistakes, it takes that element of chance out of it to a certain extent and along with it that element of surprise and credit because it’s such a perfect tool. These plastic cameras allow the emotional aspect of this art form to remain. Photography is an emotional art form and these allow that to take place, it heightens that emotional experience and some of the results will show this, you think and feel ‘wow’.

This is our 11th exhibition together, so we’re quite strong group. Every year we have a different topic and it’s either Ludlites love something; ‘Ludlites Love Water’ or ‘Ludlites Love Light’ or “Ludlites Love Nature’, some theme. This year it’s ‘Ludlites Love Film’ and everyone responds to that.

Most of the group have taken movies that they’ve liked and used that as their premise and rephotographed elements of them, which may not be accurate but these cameras allow your memory to interpret – and they look like a memory. They have fuzzy edges, the graduation in vignettes shows an appropriation of that idea that is just fascinating.

I went another way, starting to experiment with the camera and put actual an emphasis on ‘Ludlites Love Film’ and took film itself to be the idea of setting it. Film is acetate or plastic with a gelatine coating to hold very fine granules of silver. I played with that notion. I had met Avalon local Garry Phillips, the cinematographer who shot that really good movie that came out last year, The Railway Man, a beautiful film. He gave me some film, some movie stock, which I cleared and then used that.

It’s probably easier to show you;

So that one is taking acetate and painting on it, putting it in the back of the camera, putting a roll of film over the back of it, closing the camera, and looking for a subject that worked with the acetate painting. So it’s a tactile approach – it’s I don’t exactly know what I’m getting so I’ve got to feel it. (pic Billow)

When you do this of course you have to put the film in upside down and back the front – so it multiplies the chance of error. But generally you get it right I do a little drawing which I place on the back of the camera as a guide. I have different cameras with different acetates in them; so I’m looking for the scene that works with that.

This one is called ‘Billow’ and this was one that was shown down at Sylkes Gallery last year at Avalon. That was the start of the ‘Ludlites Love Film’ Exhibition because I had to present this to head on to get a gallery, so this became the token image for that.

Billow - Ludlites Love Film - Head On Photo Festival 2015

Then I started to play with to see what you can do:

This one is called ‘Farewell’ because I wanted the idea that Movies rarely shoot film now so film is leaving, but it’s not gone, it’s just leaving, as things do. In this instance I used ten year old film so it had that aged look – you can see how it has the chemical fog is happening around the edges, the red is coming in. I didn’t exactly know that was going to be there – I knew ten year old film, from other rolls I’d shot from the same batch, would have this effect, so I wanted to have that built into the image; there’s grading to get it right but it’s a straight image.

FAREWELL - Ludlites Love Film - Head On Photo Festival 2015

Preserved - Ludlites Love Film - Head On Photo Festival 2015

There’s another that goes with that which is the one on the Invitation; I put the film in a jar because it’s almost saying it’s a historical reference and born of the notion that film is a physical thing.

This one is called ‘Undine’ which is the female spirit of the water world. I went to the Australian Museum and photographed some of their sea creatures and this a star fish of some sort. They let me set up lights on a tank and I photographed them there in black and white. I then put that black and white negative in the back of my camera, put film over it and went underwater to take a shot of the water. At the Museum the specimens came in large glass jars in a preserving liquid.

Undine - Ludlites Love Film - Head On Photo Festival 2015

So these are quite layered as well?

Yes, that’s the idea, that you have to go through the process for the personal journey and that is how you get involved in it. You have got to do the work before you get the results – you will get out of it what you put into it, even if that entails endlessly thinking about it.

This is where these cameras are beautiful as it’s mostly pre-conception – it’s not like taking the shot, whacking it on the computer, buying some software and doing the work post-conception. There’s nothing wrong with that, but for me, the process is important. It grows; you take the shot, take it to the lab, you have to wait to see it and are thinking about it, about what you’ve got – so you’re adding to that process in your mind and if it didn’t work out you go back and do it again.

It’s such a wonderful tool to aid creativity.

This one is similar, called ‘The New Man’ – that’s on a building in Crow’s Nest – it’s like a plinth.

I did this shot years ago; but have kept all my negatives. I was thinking about doing something simple, with a spiritual connection that would translate from the negative to a positive. So that’s the negative of the body, you put this negative in the back of the camera, it stays a negative, but I wanted a background for it that would allow me to add more meaning to this idea.

The New Man - Ludlites Love Film - Head On Photo Festival 2015

How important is to know your equipment and what it can do?

This may sound ten years too late but you’re going to learn more using a manual camera and using film, because when you make a mistake – it’s there. You can’t correct it, the camera doesn’t correct it for you – you have to figure out what you did wrong and how you can improve on it. That notion unfortunately is going out of it, so photography is going from the right-brain creative types to the more logical those who can write software types, it’s being drawn away from the illogical to the logical.

You can do anything on a digital camera that you can do on these plastic cameras, or manual ones, but you have to be a better re-toucher than a photographer, so it gets away from the premise and the chance for something great to happen.

Can you see a difference between your first exhibition and your latest?

Oh yes. The first ones, with the plastic camera, were sort of experiments to see what I could do that worked – an accident would happen with the camera and I’d try and figure out how I did that accident. I would then try and produce more work on that same concept. That then became a sort of style – so it was more based on what the camera told me.

I’m still doing that but now it’s less concerned with producing quantity and more concerned with producing something of quality, so I think about it a lot more.

The other point of this is I don’t want to photograph something I’ve photographed before, I want to do something new, which, when I’m thinking about the ocean, I’ve already photographed a lot.

So in finding new ones I have to be inventive, for me, and make images that surprise me and show the ocean or beach culture in a fresh way. So as a result it has become quite contemplative now.

Who are your favourite photographers out of all those who have photographed anything ever?

There’s an American photographer by the name of Harry Callahan and he was a guy who struck me as the photographer who had gracefulness to his work; he could photograph a weed and make it look good, he could photograph telegraph lines and invoke something in you; he could photograph his wife, and he did photograph his wife Eleanor for 40 years, and it was that commitment to his calling – he was just special.

He coined the term ‘it’s the subject matter that counts’. He taught at the Chicago Institute of Design, which is where László Moholy-Nagy taught, which is where Aaron Siskind taught, which is where a number of great designers, photographers and architects taught. They were influential and that is still being felt. That’s why I keep coming back to the idea that the history of photography is really important to the future of photography.

We can all make one stunning interesting new looking images, but can we do two, can we get a concept that allows us to take a new direction.

The person who illustrates that best for me is Trent Parke. He will take a simple idea and expand on it – there’s a lot of technique there which goes unnoticed, a lot of knowledge and a lot of respect for the continuation of photographers rather then the new medium of digital cameras. I like that in his work.

But Harry Callahan for me was the best – he inspired me to look and see.

Do you have any photographic images that are your favourites?

There are many but, no, I guess I don’t think like that,

Not even with your own works?

No - I don’t think that way, as soon as you do define yourself in that way you set limits on where you can go. It’s those experiences where something else occurs, where the camera captures something that you didn’t have a say in, you had a part say in taking it but you didn’t control it.

Those are the memorable ones, when other things happen, where you’re not saying ‘this is my photograph – I made it’ but where you’re part of it and it’s those experiences that are really important.

A project I did a little while ago, ‘Head East’ that was the idea behind that, to go back and see if my memories of a place were like I remembered and how my camera saw those scenes. I did the 91 roads that end up at the beach between Palm Beach and Manly. Certain things hadn’t changed, they were very similar to what they were when I was a kid. That was great – I hate this idea that a Town Planner comes along and says ‘I want to make all the beaches look the same’ – my idea was to say that all these beaches are unique and every one of them has their own different character and different people see some quality there growing up in this. So I did this idea of a shared history that was my interpretation of this through these roads that all ended at the beach.

So I was trying to rely on, not necessarily reason, or relevance, but what I remembered from when I was younger and in the process, discovered things I didn’t know existed, such as there’s a little cave down at Bilgola or one road that has no name, it’s just there and has these houses and no sign and this brings in that it’s just local knowledge that would help you find or see these places, these roads that all end at the beach.

Head East; It’s like being a passenger in a car and you’re looking out the window – once you become a photographer you’re looking for something – somehow something happens where you’re not just looking and saying ‘isn’t that pretty’ or ‘isn’t that amazing’ – you’re actually looking for something, there’s a language going on which is a visual language that you can see when you’re driving along – references that you’ve seen before in other people’s work, or ideas that you wanted to execute, but now I’m a driver all the time I have sort of lost that.

Head East shows this principle though – this turning left and seeing these glimpses of these shorter roads that all end at the beach – it took three years to shoot and the final print is 22 metres long – and that’s just one single print.

Fantastic!

Well, I don’t know; it’s just a project I wanted to do. This is the poster I made out of that for the Exhibition. So this is the shared history idea; that’s the lighthouse at Palm Beach and the last one, all through Narrabeen, Collaroy etc, is you end up at North Head looking across the Sydney Heads to Vaucluse and the Macquarie Lighthouse.

Now my great grandfather built those two lighthouses.

So this idea of how photography happens is, when you’re driving from here, from North Narrabeen all the way to Long Reef are about 25 roads, little roads that have been cut off by Pittwater Road, so when driving along you are eyes front and turning your head to see what the surf is doing – everyone does it – and it occurred to me that that movement is like taking a picture – and later on this made more sense and this was like taking a mental picture and you make up the difference in your head; what the wind is doing, what the swell is doing.

Head East

Beautiful – that’s brilliant. So was photography a revelation for you when you discovered in America or can you recall instances of being aware of what a vision is prior to that?

The revelation was, and continues to be, that a photograph can subtly change the way things are perceived to be. The challenge is to find that.

Captain Francis Hixson – is he your great grandfather or great great grandfather?

I think it’s great grandfather as he died in 1909 and I was born in 1950. I remember my father but I don’t remember my grandfather, I never got to meet him, but he was my grandfather’s father.

What are the family legends that may not have appeared in records?

There’s not many, it wasn’t really talked about that much – he was just this guy in a picture with the mutton-chop whiskers. Bronwyn reckons I look like him and sometimes I act like him in being the captain of the ship. (laughs)

You may be aware that two of his daughters married Fairfax sons. One of the first jobs he did when in charge of Ports was go to the Clarence River to investigate a claim where a chap was suing the government for 10 thousand pounds. He investigated it and got it reduced to one thousand pounds. But the chap who lost the nine thousand pounds then went on to be Governor of NSW and had a set against Captain Hixson but due to two of his daughters marrying Fairfax sons the persecutions this chap then levelled against him never appeared in any papers as these, then, were the history and records for that time. Some say he never received promotion due to this episode or incident. This is why his history isn’t clear cut, although he as clearly a fantastic man.

The other thing spoken of is that he was into looking after all sailors – he started the Sailors Home, which was down near The Rocks - so they could still look out and sea the water.

You know he was there the day the first Royal Visitor here was shot, Prince Albert, who had just handed over a cheque towards the Sailors to him – he was pretty amazing, all the things he started...

Yes, he began the Naval Brigade too, designed the NSW flag – and apparently he listened to people, wasn’t arrogant, possibly another reason he didn’t go onto a higher office.

He seems as though he really loved the sea foremost - didn’t want to shift away from being on the water..

That’s what his family did in Swanage - where he was born, he was very young when he started mucking about on boats. My father was quite old when he had me so it wasn’t really spoken about that much.

I remember my auntie, dad’s sister, had this house full of beautiful furniture. It was a little farmhouse with awnings and filaments on it – it would take hours to get out there.

So in respect of that this work (Head East) was that shared history and in respect of my family’s history within the area as well.

Surfing – you have given the championship swimming away now but you’re still getting in the water?

No, I don’t go in pools anymore but I do swim across the beach. I go body surfing almost every day, body-surfing allows you to keep going as you’re not wrecking your joints.

I surf at South Avalon with the muppets; they’re a great group of people; Ian White, Warwick Wilcoxson, Bruce Raymond, Jim O’Connor, John Little, Richard Helm, John and David Archer, Michael Fay, John Hollingshead, Don McCreedy, Phillip English and a bunch of others, it’s a lively and interesting group.

What are your favourite places in Pittwater and why?

When we lived up on Bangalley headland I did a lot of photographs of the headland and I really like that spot, it’s very private. When you get down onto the rockshelf it changes, you’re overwhelmed by the ocean on one side and that shelf of rocks on the other and you’re vulnerable. That experience, to me, is quite rewarding, especially if you have a camera and can record something. (pic. headland 1 and 9)

I like all of Avalon Beach, I don’t discriminate between north and south – it’s all good.

To me the whole of it is all good – this Head East taught me that every beach has some unique quality and you just have to find that – they’re all beautiful, they’re all worthy places to be. If we lived in the Western Suburbs our kids would be going to a mall to hang out, but here, we go to the beach to hang out; it’s all open, it’s all healthy, you’re always testing yourself against the elements and you can go along with it and be part of it, which is also part of what being in a surf club is all about.

When did you join Avalon Beach SLSC?

I did a book called ‘Beach’ in 1998/99 and part of that was like a year in the life of Avalon Beach, all shot with plastic cameras, in black and white, hand-printed for the Exhibition and it sold lots of copies of the book and the images were exhibited around the world.

Wow – love this one;

Beach: that’s Chelsea Jorgenson and my son jumping of north Av. rocks –

Jump rock - from Beach - Friendship

It was like recording these figures – this is a really interesting part of Avalon as it’s where adults don’t go, this is just for the kids, their place. There will be kids waiting there to take their turn, or watching, learning, they’re not quite ready to do it and then one day they’ll be old enough and brave enough to and one of the older kids will show them how to do it; how to jump, when the tide is right, all that stuff

Part of the beach is the surf club of course so I thought I’d better look at that. Roger Sayers saw me swimming around from Bangalley and then around the headland and said “you should join the surf club” and I thought it would be good to give something back and so I joined. It’s been a lovely experience.

So now I’m with the surf club I do Patrols, and have for quite a long time now, which is great; you’re mixing with people of all different ages and interests. I do the Sunday Swim, I’m the handicapper there which is really fun and good for people to come in and try a swim and test themselves, get handicapped and win a prize and enjoy the ocean. So seven months of every year we’re down there of a Sunday morning having a swim.

What an extraordinary body of work – how many photographs d you think you have taken?

I don’t know (pulls out one drawer from one filing cabinet); that’s plastic camera. Right now I’m shooting less and less but hopefully they’re better!

What is your ‘motto for life’ or a favourite phrase you try to live by?

You can come out of the surf younger than when you went in.

Notes and Extras:

Avalon BEACH SLSC - Swim Captain/Handicapper – Tim Hixson.

It's the Hixson Family week this Issue - Captain Francis Hixson opens June 2015's History pages as the second in the series of Pioneer watermen of Broken Bay and Pittwater

Beach – taken with a Holga camera: www.holgacamera.com

Exhibitions

Christmas Cards, Not Quite Square, Head East, Headland, Beach, Waterlogged, Dukes Hand, Sharkey, Sea Change, Non Series, Life, History of Leaves

More Tales from the Sea Press - 2006

‘Toy camera’ images capture contemporary Australian beach culture in Tim Hixson's photographic exhibition, Sandra Byron Gallery, opening 19 October 2006. More Tales from the Sea is the result of Hixson’s ongoing love affair with the ocean. A keen surfer and ‘waterman’, Hixson’s photographs convey his deep enchantment with the ocean through the ethereal quality of his images captured by a simple plastic camera. Showcasing three series of works, including ‘It looks a bit sharkey out there’, ‘Waterlogged’ and ‘The Dukes Hand’, the exhibition presents a range of exciting new images, until 30 November. Most recently announced as the winner of the Art Photographer Award by Capture Magazine Australia’s Top Photographers 2006, the Sydney based photographer’s signature is his exploration of plastic (Holga) cameras used for recording and interpreting Australian beach and water culture.

Plastic cameras were first made in Hong Kong in the early 1960’s. Using 120m size film, they have very few exposure controls. The lens is a single piece of curved clear plastic which flares direct light, softens the detail and darkens the edges to give the images their characteristic charm.

“You can’t hide from the image that’s taken on these cameras. The quality of the image is what the plastic lens doesn’t show; how it merges one object into another and how it simplifies a scene. It’s the realistic beauty of the shot taken at that one specific moment,” Tim Hixson said. Plastic cameras are the direct antithesis of complex digital photography processes. Hixson has been at the forefront of a growing trend for low-tech plastic cameras. Hixson describes the medium as “a tool to produce an abstract view of the ocean and my own coastal community… providing the potential for chance and surprise in capturing the image.”

In More Tales from the Sea, Hixson expresses the light of summer and shares his unique perspective on beach culture, the immense power of the ocean, intimate views of personal contact with the water, and what he refers to as the ‘darker side’ of surfing. Cont/d… 3 His work succeeds is blending the dichotomy of the every day with the ethereal, the extraordinary with the familiar, mythology with contemporary culture, and man with the sea. Tim Hixson: More Tales from the Sea 19 October – 30 November 2006 Sandra Byron Gallery 11/2 Danks St, Waterloo, Tuesday-Saturday 11-5pm, www.sandrabyrongallery.com.au, www.timhixsonphotography.com.au

BIOGRAPHY TIM HIXSON - PHOTGRAPHER

Using the unique style encapsulated by plastic (Holga) camera, Tim Hixson has recorded and interpreted Australian beach and water culture. More Tales from the Sea, is the manifestation of his plastic camera images since his last book of images “Beach”, and successful previous solo exhibitions, “Waterlogged”, “The Duke’s Hand” and “It looks a bit sharkey out there”. It also includes a group of new images including ‘women preparing to swim’ and ‘Sea Change’.

Born in Adelaide in 1950, Hixson has lived in Sydney since the age of three. His youth was spent leaving near the ocean and the local pool.

A champion swimmer and keen surfer Hixson continued swimming competitively whilst based in the U.S.A. where he gained a Bachelor of Science in Cinema and Photography. Since then, Hixson has exhibited his photographic work in Australia, Japan, Paris and the U.S.A. His unique approach evokes his love of photography, the ocean and Australian beach culture has won him acclaim amongst his industry peers and art critics alike. He was recently recognised as the winner of the Art Photographer award in the 2006 Australia’s Top Photographers by industry magazine, Capture.

The Sydney Morning Herald’s Robert McFarlane describes Hixson’s work as “An enchanting modified ‘reality’ … his camera creates images of the beach suffused with romantic impressionism and gentle optical aberrations.” Carmel Finegan from COFA artwrite magazine wrote, “Hixson’s exhibition infuses an otherworldly dimension into vistas and visages from other times … The artist succeeds in subtly facilitating the recognition of the extraordinary in the familiar.”

Hixson has been shooting with plastic cameras since 1969 and enjoys the strong element of chance in his medium.

“Unlike perfectly executed digital images … with plastic cameras, you can never quite predict the outcome. I work on the interplay between the foreground and background and am always being surprised with what the camera gives back”, Hixson says.

Australian Commercial and Media Photographers

Australian Commercial and Media Photographers (ACMP) established in 1991, acts as a united voice for Australian professional working photographers.

Australian Commercial and Media Photographers (ACMP), established in 1991, is an organisation based upon the idea that we are membership driven and that we are collectively the united voice for Australian professional working photographers within the commercial, advertising and media sectors.

ACMP is committed to the development and promotion of professional photography. Our bi-line "The ACMP is your partner in photographic excellence" was born from the idea that we want to be perceived as a platform to develop and educate the professional photographer in all areas of business and what is required to be successful in today's environment. See: acmp.com.au

Tim in his home studio. Photo: AJG