August 9 - 15, 2015: Issue 226

Sailing with Cook: Inside the Private Journal of James Burney RN

The two ships, Adventure and Resolution, of Cook's second voyage, drawn by Peter Fannin, the Adventure's talented master, nla.gov.au/nla.map-nk10592a-7 (p54-55)

Sailing with Cook: Inside the Private Journal of James Burney RN by Suzanne Rickard

A few weeks ago we received an extensive and beautifully illustrated book released this month by the National Library of Australia: Sailing with Cook: Inside the Private Journal of James Burney RN. Having recently spent time researching early Sydney Captains, and discovering Captain Thomas Watson had been befriended by Captain Cook's wife as a youngster and subsequently went on to ensure one of the earliest statues to this gentleman was raised, in his own front yard!, our curiousity soon turned to delight when reading through this wonderful hardback volume of a journal by one of those who sailed with James Cook.

This work has been carefully researched and with maps, portraits, contemporary documents and artefacts, including information text boxes on people and issues placing context on the journeys and voyages it charts - this is one for all sailors, historians young and old, and even for those who love great art and its place in our development before the advent of the photograph.

When we spoke to the author, the equally delightful Suzanne Rickard, she reminisced about time spent at Ingleside and relatives whom she still visits here before we began speaking about the great trove of journals being newly discovered by this generation of Australians, people who want to hear the thoughts and imagine the views of those who have stood here before we did. This focus is an aspect the National Library of Australia continues to excel in, making this journal available in a digital format as well as continuing to make available all the newspapers that once flourished Australia wide, and thereby, all in them, as well as being the storehouse for many paintings, illustrations, photographs and equally wonderful tomes.

Captain Watson and his Captain Cook statue in his front yard, and that placed in Hyde Park a few years later, runs here next week - which we hope will inspire others to gaze at these when next they are in their vicinity. This Issue Suzanne kindly answered a few questions about her new book:

From reading so much of James Burney in his voice - how would you describe his character?

Gathering descriptions of James given by his famous (and loving) younger sister, Fanny Burney (Madame D’Arblay), the novelist and diarist, as well as gleaned from comments from his distinguished and much older friend, the lexicographer, Dr Samuel Johnson, and another old family friend, the bibliophile, Samuel Crisp, we can confidently assume that James certainly had plenty of “character”, and this was probably obvious from an early age. Many of his land-bound friends and family quickly nick-named him “Jem the Tar”, indicating that he quickly became a naval man in his speaking and manner having become a captain’s servant from the age of ten. However, in later life, Dr Johnson, was surprised that having spent so many years with “sailors and savages”, Burney was “gentle in his manners”. I think that Burney was a boisterous and enthusiastic young boy and this element of his character and personality remained throughout his life. He was honest, perhaps occasionally, too honest; he was evidently witty, humorous and enjoyed company.

Gathering descriptions of James given by his famous (and loving) younger sister, Fanny Burney (Madame D’Arblay), the novelist and diarist, as well as gleaned from comments from his distinguished and much older friend, the lexicographer, Dr Samuel Johnson, and another old family friend, the bibliophile, Samuel Crisp, we can confidently assume that James certainly had plenty of “character”, and this was probably obvious from an early age. Many of his land-bound friends and family quickly nick-named him “Jem the Tar”, indicating that he quickly became a naval man in his speaking and manner having become a captain’s servant from the age of ten. However, in later life, Dr Johnson, was surprised that having spent so many years with “sailors and savages”, Burney was “gentle in his manners”. I think that Burney was a boisterous and enthusiastic young boy and this element of his character and personality remained throughout his life. He was honest, perhaps occasionally, too honest; he was evidently witty, humorous and enjoyed company.

One shipmate described him as ‘Excentric’ (sic) but didn’t explain what he meant by this. It might have referred to Burney’s interest in learning. He could be very disciplined and he diligently learned all the required practical seafaring skills as well as book-based mapping and calculation skills so that he could qualify for naval promotion. It took 6 years’ service before young men could take the naval examination for the rank of Lieutenant. Burney went to sea as a captain’s servant (arranged by his father) as he was too young to enrol in the Royal Naval College. He was clearly ambitious and encouraged by his father.

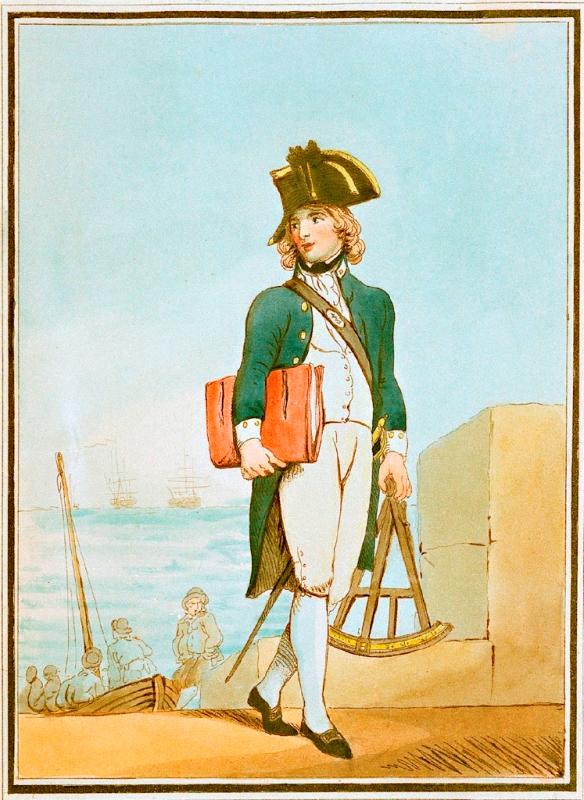

Right: Midshipman 1799 by Thomas Rowlandson - National Martime Museum, Greenwich, London Image PAF4970 - page 24

While Burney could be boisterous in company, when on duty he held his emotions in check. Similarly, he was factual when writing his private journal and, of course, when updating the Ship’s Log. He wrote concisely and practically. But this is not to say he was without emotion. (More of this in relation to Q. 3).

Throughout his life, Burney was driven to educate himself more widely and, given certain family tensions, I believe that he was also driven by a need to impress his father. As a young sailor, he often took a chest of books to read at sea to improve himself. Of course, as a Lieutenant, the required essential skills of charting, mapping, oceanography (winds, currents, weather) and sketching land profiles, navigation, etc., were well honed and practiced, and colleagues regarded him as a thoroughly reliable and trusted mariner.

Captain Cook wrote that Burney’s promotion to the rank of Lieutenant was “well deserved”, which indicated Cook’s assessment of a consistency in Burney’s performance and character. Burney was also brave, demonstrated not only in various sea battles across his years of service, but also when finding the remains of his shipmates in Grass Cove in December 1773 and avoiding further violent skirmishes with the Māori. His courage was on show again in February 1779 when he and Lt. James King went ashore to attempt to retrieve Cook’s body from the then enraged Hawaiian.

When Burney was effectively retired from active service from 1785 onwards (as he was not offered further commissions by the Admiralty for reasons I explain further in the book), according to one of his sisters, (Mrs Susan Phillips writing to her sister Fanny in 1787), he spent hours each day studying philosophy, economics, history, law, physics, science, Latin and French. He apparently set himself a goal of adding 100 pages a day of close reading until he had acquired the requisite knowledge. So, he was determined to broaden his knowledge through scholarship and attain status this way. He always had an enquiring mind and a lively intellect.

According to those who knew him (beyond naval circles), James was an amiable and humane person, a man who, although shaped by his naval and seafaring years in the company of men, could hold his own in polite and esteemed company (although his humour was sometimes a little risqué for his sisters). It was Burney who chaperoned and translated for Omai, the young Islander he met in Raiatea. When Omai was presented to King George III and Queen Charlotte at Court, Burney was by his side, and he introduced Omai to Sir Joseph Banks, as well as other distinguished 18th century personalities. He evidently had linguistic skills and musical training as he made musical notations in his private journal.

Other distinguished mariners and navigators trusted Burney’s skills and judgement, including William Bligh and Matthew Flinders. Captain Cook trusted him sufficiently to call him back to serve with him on the Discovery on the 3rd voyage of exploration, and Sir Joseph Banks also consulted Burney on the production of Cook’s journals prior to publication. These are all indications of people trusting Burney’s character.

James Burney did not appear to be very religious, although he would have participated in the Sunday prayer services on board HM’s ships.

James Burney came from a talented and literate family - how did this help his written works as A) a Journal keeper - and B) later publications?

James Burney was fortunate that many of his father’s friends had books and extensive libraries. They were generous in allowing young James access to their collections of books and maps when he was ashore. This access was given as a compliment to Dr Burney who was well-established as a keyboard musician (harpsichord mainly) and scholar of music and a visitor to many stately homes. Dr Burney established his own extensive library and writing was certainly commonplace in the Burney family circle. Thus Burney learned as much by example as through developing his own writing talents and style. While he was frequently separated from Fanny and the family through his sea voyages, the Burney correspondence exchanged was voluminous if necessarily infrequent. Fanny Burney’s own ‘journalising’ and letter-writing must have inspired Burney, as well as the example of his father’s writing. His private journal was, as he stressed, written for his family and friends, chiefly for their amusement!

When James was finally ensconced in London after 1785 after his final naval commission, he took to scholarship and writing with gusto. He also had open access to Joseph Banks’s library, a privilege extended to but a few. Burney first developed his editing skills, then segued into writing short polemical and radical pieces on current affairs, including economics and defence affairs. While he was never a lyrical or ‘Romantic’ writer, he was complimented by contemporaries for his thorough research, his orderly presentation of facts, i.e., his methodology, demonstrated most strongly in his series of published volumes of chronological histories of voyages of discovery (A Chronological History of the Discoveries in the South Sea or Pacific Ocean, 5 vols. London, 1803-17). He also wrote a number of scientific papers for the Royal Society, on topics such as water currents, astronomy, measuring a ship’s rate of sailing, ascertaining if there was a North-West passage, as well as a memoir of sailing the coast of China and the southern islands of Japan.

Burney witnessed Cook's death, a horrific frenzied attack as per his description in which he was unsuccessful in retrieving the body - what was his opinion of Cook if you read between the lines of his journal - one of esteem, fondness or ...?

It would not be overstating to assume that Burney, like all naval men and sailors, had great respect and esteem for Captain Cook. As a young man, he lobbied hard to get a berth on the Resolution on the 2nd voyage of exploration to the Antarctic and Pacific, so that he could sail with Cook whose reputation had soared after the first successful voyage of exploration. He was pleased and proud to have been requested by Captain Cook to return from naval duties on the American coast to serve as 1st Lieutenant on the 3rd voyage of exploration on the Discovery, the second vessel. He served directly under Cook’s command twice and there witnessed his seamanship, his leadership, and his intelligence. His official account of witnessing Cook’s death in Hawaii is calm yet poignant, one might even say ’manly’. No gushes of emotion as this was not fitting an officer.

The SLNSW transcription of Burney’s account of Cook’s death and the attempt to retrieve his body described ‘James Burney's recording of Cook’s death is one of the most concise and sober of the accounts. He describes the events as they occurred, injecting no emotion into the account, however much he may have been affected personally.’

Like all aboard the Resolution and Discovery, Burney was shocked and dismayed, but he also knew that as an officer he had to provide a strong example to the ship’s company. Emotions were private to the individual, and facts were essential to Burney. The

While speculating calls for caution, I have often wondered, had Cook lived to serve again, if he would have requested that Burney sailed with him on further voyages. I suspect that the answer would have been yes, and I think that Burney would have accepted.chain of command required that within weeks, Burney was transferred back as 1st Lieutenant to the Resolution. One may assume that he felt flattened but needed to carry on regardless. This is where his training came into display.

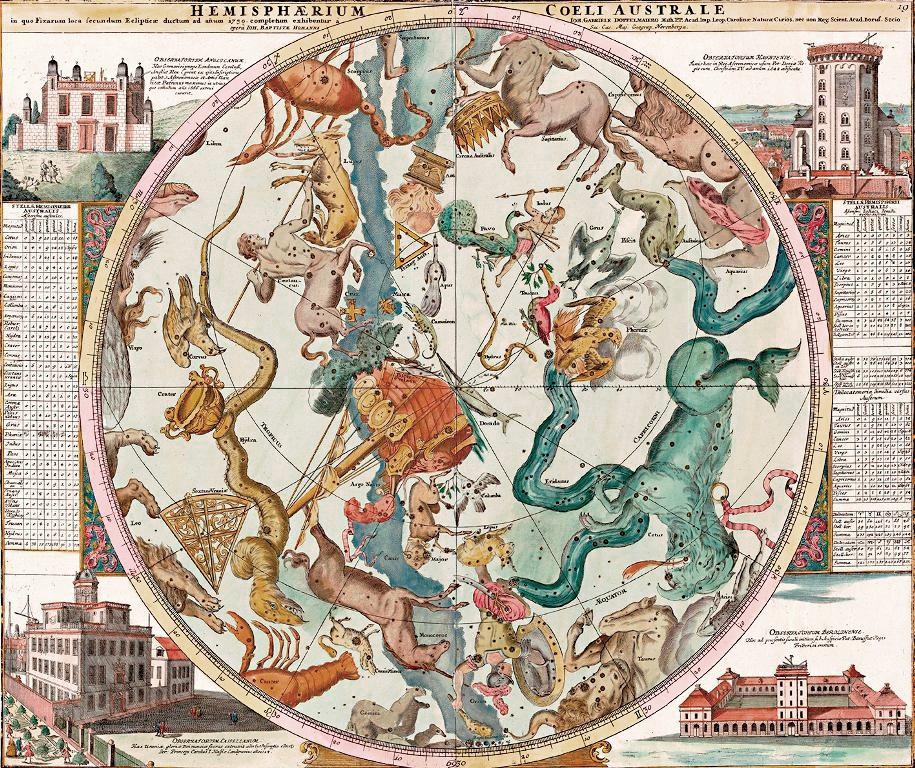

Navigation by Stars - Burney travels to places never seen before and witnesses peoples and cultures never seen - what stood out most for him, even after years had passed?

Burney did not wax lyrical in print about many of the places he’d visited (although he may have spoken more about it). Given that he’d sailed to Istanbul, the islands of Madeira, Bombay, Madras, Cape Town, as well as the east coast of North America and the northern coast of South America, as well as Macao, the southern coastal islands of Japan and into the northern waters near Alaska, he decided to leave descriptions to those who had done this before him, as he wrote, ‘I have not the least inclination to attempt a description of a place that so many have described before me.’

But, in his private journal, his descriptions of seeing icebergs and ice fields are striking, as are his descriptions of the Tasmanian coastline and Adventure Bay, as well as witnessing ceremonial events in the Pacific islands. He made particular note of the displays of dancing and singing, ritual greetings as well as ritual war dances, he wrote about native myths, about the demeanour of ceremonial priests and head-men, the variety of native dress, the women and children, weaponry, canoe-building and body tattoos. These impressed him deeply as he wrote about these in such detail on the second voyage.

Right: Table of star signs and dates, compass, spirit level, sundial, astrolabe and measuring instrument in a wooden box] [1750?] 1 set instruments : wood, bronze and glass ; box size 3.3 x 43.7 x 9.9 cm.nla.pic-an7905959 page 147

What also stood out strongly in his mind (and in his journal) was that although the British and other Europeans navigators had ‘discovered’ places remote from the Northern Hemisphere, he observed that the native peoples inhabiting all these places had their own social organisations, hierarchies, belief systems, status systems, land tenure and strict inheritance arrangements. In other words, he recognised their ownership of their lands and showed respect for their customs, even if he described some as ‘barbarous’.

Burney’s ability to quickly learn, absorb and speak in ‘Tahitian’ (recalling that Omai’s origins in the Society Islands: http://www.tahiti.com/islands/society-islands), impressed many people. When he researched and arranged his chronologies of earlier voyages of exploration, one must assume that his mind’s eye was busily at work recalling his visits to various islands and sailing along the ‘edges’ of continents.

Also, it’s worth remembering that Burney kept in close communication with former ship colleagues (including William Bligh and Matthew Flinders) so that conversations about places they had visited would have remained very alive in his imagination. His friendship with Omai was unique and again, one must assume that he referred to this to friends throughout his lifetime. He accompanied Omai back to his native islands on the 3rd voyage of exploration in 1775. I can well imagine that Burney may have occasionally been asked or used phrases from Omai’s language to amuse his family and friends.

Doppelmayr, Johann Gabriel, 1671-1750. Hemisphaerium coeli australe in quo fixarum loca secundum eclipticae ductum ad anum 1730 [cartographic material] 1742. MAP RM 3532.http://nla.gov.au/nla.map-rm3532 pages 146-147

Burney goes on to write and publish many works, including the five volumes of 'Chronological History of the Discoveries in the South Sea or pacific Ocean' - what, in your estimation after researching his works, was his major contribution?

Burney’s major contribution, acknowledged by contemporaries and still today, is the chronological and sequential histories he arranged illuminating the explorations of the world’s oceans and the discoveries made by all seafaring nations of Europe. The Quarterly Review of 1817 (then an influential journal), described the full set of chronologies as ‘a masterly digest … a rare union of nautical science and literary research’. Today, scholars regard Burney’s observations made in his private journal as providing valuable ethnographic information in an anthropological sense. His first-hand observations, untainted at the time by formal scholarship, provides an ‘eye witness’ account which now informs a number of detailed academic studies. On another level, his combative essays written in the late 1780s and early 1790s criticising government expenditures or suggesting alternative defence plans, illuminate the thinking of many of the radical persuasion of the day.

Landing of Captain Cook in New Zealand - E. F.Temple (1835-1920) painting dated 1769 1880 nla.gov.au/nla.pic-an6054544 - Pages 172-173

Sailing with Cook: Inside the Private Journal of James Burney RN

Author: Suzanne Rickard - Publisher: National Library of Australia - Edition: 1st Edition

ISBN: 9780642277770, Pages: 264, Publication Date: 01 August 2015, Price $49.99

Overview

Sailing with Cook: Inside the Private Journal of James Burney RN is about the young James Burney’s experience of shipboard life and the momentous events that took place during the second voyage of exploration when he sailed with Captain Cook on the Resolution and then on the Adventure between 1772 and 1773.

Sailing with Cook: Inside the Private Journal of James Burney RN is about the young James Burney’s experience of shipboard life and the momentous events that took place during the second voyage of exploration when he sailed with Captain Cook on the Resolution and then on the Adventure between 1772 and 1773.

At the age of 22, James Burney (1750-1821) was promoted to the rank of 2nd Lieutenant. Embarking on a great voyage he decided to keep a private journal written not for officialdom but for the delight and information of his family and friends. It was an aide-memoire, a record of his coming of age and the getting of wisdom. He claimed at the outset, ‘my chief aim is your amusement’.

Under the command of Captain James Cook and Captain Tobias Furneaux on the Adventure, Burney crossed the Antarctic Circle, he was one of the first Englishmen to walk on Tasmania’s southern beaches, he endured raging seas and icy weather, he sailed to New Zealand’s South Island and into its beautiful sounds, and then he sailed further north to explore the tropical waters of the islands and atolls of Polynesia.

Burney witnessed death at sea from misadventure and scurvy, and he experienced the shocking death of ten shipmates at the hands of Maori warriors. He enjoyed cordial advances from Pacific Islanders and the friendship of Omai, a young Ra'iatean man who became the second Pacific Islander to visit Europe. Burney listened carefully to island music making (to please his musician father), witnessed religious ceremonies and observed Pacific Islanders’ hierarchies. He noted the building of war canoes and absorbed ancient Pacific myths and lore of navigation. All these experiences expanded his world view. This was in addition to working with his captain on making charts, maintaining ship’s discipline and the ship’s log, and upholding naval traditions as expected of a young officer.

Burney’s early life and his extraordinary family and connections are contextualised to illuminate the story of the private journal. Burney’s extensive naval career took him to North America, the Mediterranean, the African continent, to India and the East Indies, to China, Alaska and Hawaii. He sailed again with Cook on the third voyage of discovery in 1776 and witnessed Cook’s death at Kealakekua Bay, Hawaii, in 1779.

Burney’s naval career was hindered by his independent frame of mind, if not his republican sentiments and alleged insubordination. Despite setbacks and disappointments, he was eventually promoted to the rank of Rear Admiral on the Retired List in a belated recognition of his service and seniority.

In enforced retirement, Burney commenced a second career as a writer on the topic of global marine exploration. He married late, had children and, for a time, he was embroiled in an unorthodox domestic arrangement. He criticised government expenditures, he wrote a series of scholarly papers for the Royal Society and was elected a Fellow, he was highly respected for his studies of exploration and navigation, and he maintained eclectic circles of friends drawn from musical, literary, dramatic, naval and political circles.

He was an amiable friend to many, including his famous sister, the novelist Fanny Burney who championed James throughout her life. Burney died in 1821 leaving a legacy of writing, including this first private journal that opened up a new world to his friends, and now to us.

This book features facsimile pages extracted from the private journal and is beautifully illustrated with maps, portraits, contemporary documents and artefacts, including information text boxes on people and issues. It follows the successful format of other books such as In Bligh’s Hand: Surviving the Mutiny on the Bounty.

___________________________

Suzanne Rickard is a historian and writer. She was a contributor to the National Library of Australia’s Centenary publication, Remarkable Occurrences, providing a chapter on the Maps Collection. She has also contributed a number of articles on the Library’s collections.

Suzanne Rickard is a historian and writer. She was a contributor to the National Library of Australia’s Centenary publication, Remarkable Occurrences, providing a chapter on the Maps Collection. She has also contributed a number of articles on the Library’s collections.

Suzanne is the editor of George Barrington’s Voyage to Botany Bay: A Convict’s Travel Narrative of the 1790s (2001). With James Broadbent and Margaret Steven, she co-authored India, China, Australia: Trade and Society, 1788–1850 (2003), produced for the Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales.

Suzanne has written a number of entries for the Dictionary of National Biography, the Australian Dictionary of Biography and An Oxford Companion to the Romantic Age: British Culture 1776–1832.

She has written literary reviews, scholarly articles, television reviews and official reports for the Commonwealth Parliament and she was Project Manager of the first volume of the Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate (2002).

Her ongoing research project, The Blaxland Women, will be the extraordinary history of three generations of women in the 1700s and 1800s: Matriarch Harriotte Blaxland, her daughters and granddaughter, linked by birth and marriage to one of Australia’s great dynastic families, with ties in New South Wales and colonial Calcutta.

Until her retirement in March 2013, Suzanne was State Director (NSW and ACT) of the Committee for the Economic Development of Australia. She now concentrates on writing and historical research.

NLA Publications:

Remarkable Occurrences -

Sailing with Cook: Inside the Private Journal of James Burney RN

Naval Architecture - Plate 1 in An Universal Dictionary of the Marine, or, A Copious Explanation of the Technical Terms and Phrases Employed in the Construction, Equipment, Furniture, Machiery, and Military Operations of a Ship - by William Falconer (London: Printed for T. Cadell, 1769) Australian Rare Books Collection nla.gov/na.aus-nk4232-slx - pages 36-37