November 10 - 16, 2013: Issue 136

Kenneth Lindsay Wright

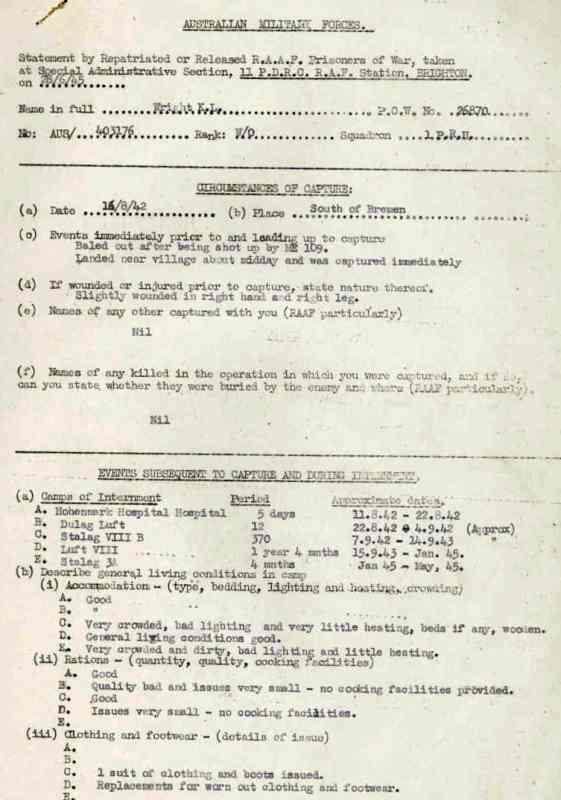

RAAF No. 403176

Flight Sergeant

PRU at Benson UK (Photographic Reconnaissance Unit - RAF), before squadrons were formed.

Kenneth Lindsay Wright (nicknamed "Lofty" for being 6'5" during his POW days) was born on the 30th November 1920 at Ballina NSW. Ken was working as a Bank Teller in Tamworth when the recruitment train came along. He entered RAAF service on the 9th December 1940 just days after his 20th birthday.

He was assigned to No. 9 course with No.6 EFTS Tamworth, then on to No.3 S.F.T.S Amberley on the 11th April 1941 flying Avro Anson's and qualifying as a service pilot on the 25th July 1941. He was destined for bomber command in the U.K. when bad health probably saved his life and he was reassigned to Spitfire reconnaissance. After a couple of minor crashes, and a close call with 5 x FW190's he was shot down and captured on his 20th mission.

More luck came his way when he was incorrectly reassigned as an officer in Stalag 8b and later Luft 3 and his chances of survival increased with the extra privileges of being an officer. He survived 3 years of captivity.

Aircraft flown — Tiger Moth, Avro Anson, Miles Master III, Airspeed Oxford, Blackburn Botha, Supermarine Spitfire Marks I and IV.

Air force assignments -

• No. 9 course - 6 EFTS Tamworth from 6th Feb 1941 to 4th April 1941

• No. 3 SETS Amberiey from 6th April to 20th July 1941

• No. 3 S of GR Squires Gate Lancashire England from 24 Nov 1941 to 24 Jan 1942

• P.R.U. (Photo Reconnaissance Unit) Squires Gate from 16th Feb 1942 to 21St March 1943 • B.A.S. Blind Approach School Watchfield, Wiltshire from 24 Mar 1942 to 1st April 1942

• "K" Fit P.R.U. Detling, Kent from 4th April 1942 to 17th April 1942

• "D" Flt P.R.U. Benson then Mount Farm from 4th Apr 1942 to 30th June 1942

• "F" Fit P.R.U. Mount Farm from 15t July 1942 until being shot down over Bremen 17th August 1942 - remainder of the war was described to him by a German interrogator as "For you the war is over"

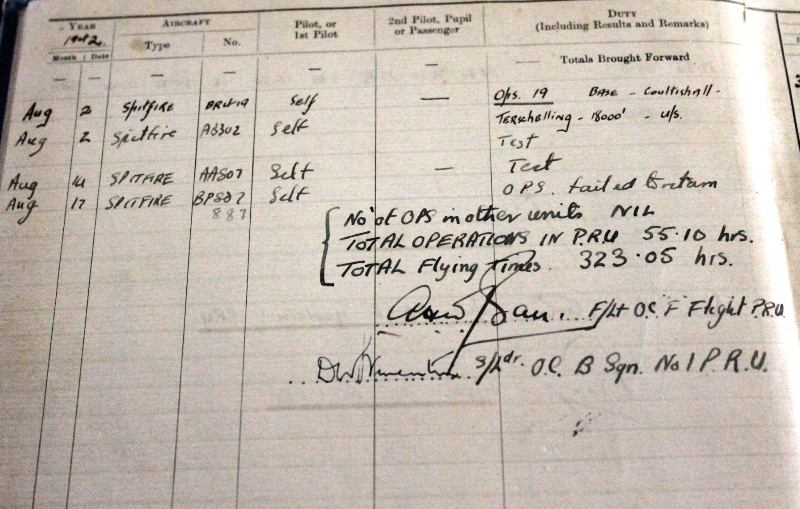

• Total Flying times 323 hours and 20 operations in unarmed spitfires over enemy territory

Some names from No.9 Course Amberley 11th April until 24th July 1941 - Besley, Dowling, Vickers, Hosband, Greenwell, O'Reilly, Goodwin, Moody, Hassall, Roberts, McRae, Williams, Watson, McGoldrick, Olive

Tiger Moth rego's — A17-66; A17-109; A17 - 112, A17 - 74, A17- 68, A17- 71.

Spitfire — X4490; R7131; R7030; X 4435; R7029; R 7211; AR 244; AB426; AR244; AB 120; AB462; BP 936; AB309; P9518; AB309;P9518;BP 926; BP 924; R7032; BP891; AB923; BP886; BR419; BP591; BP887; BR419;AB302;

93 year old Ken can tell his story better than anyone else as follows: -

93 year old Ken can tell his story better than anyone else as follows: -

Once accepted by the Air Force I attended night school at the local high school run by teachers on a voluntary basis. I studied subjects that were supposed to help us when we started our Air Force training. I thought I was lucky to be posted to Tamworth to learn to fly a Tiger Moth. My flying Instructor was the commanding officer Sqn. Leader Thomson. He had a reputation; all of his previous pupils had been scrubbed as pilots and became observers or air gunners and it seemed as if I was destined for the same treatment. This did not occur and I was the first trainee to be passed even though he only classed my flying ability as "average". His recommendation was that I would be trained as a fighter pilot but the air force did the opposite. I was posted to Amberley and had no trouble learning to fly the Avro Anson and after two months was graded as "above average" and after four months graded as "Average plus".

When I obtained my service pilot qualification I was aged 20 and still did not have a licence to drive a motor vehicle. I had some embarkation leave and then left on 8th August 1941 on the S.S. Awatea with the mates I had trained with and a number of other "rookies" who were on their way to do their flying training in Canada. We were all looking forward to a day ashore in Auckland; however on the day of arrival it was obvious I had a dose of the Mumps. My mates decided that this should be hidden or their shore leave would be cancelled. I wrapped a scarf around my throat and went ashore but by curfew time and numerous glasses of beer I was feeling pretty seedy and prior to the ship leaving reported sick and ended up in hospital in Auckland.

I lost contact with my mates and when recuperated was taken to a New Zealand air force station near Wellington and eventually set sail for the U.K. with a group of N.Z. Air Force personnel on the S.S. Rimutaka. We sailed through the Panama Canal and up to Halifax Nova Scotia where we joined a convoy to cross the Atlantic disembarking on 19th October 1941. We were billeted at Bournemouth awaiting transfer to operational units and I stayed with the New Zealanders as all my mates had gone to OTU's.

This probably saved my life as most of the guys I trained with at Amberley were killed on ops flying bombers by early 1942. With several New Zealand guys I obtained a posting to No.3 school of general reconnaissance at Squires Gate. Then off to RAF station near Blackpool to do a 6 week course as a navigator. This was expected to lead to a posting flying in a coastal command squadron. The course commenced on my 21st birthday and finished a few months later and was mainly concerned with navigating over the sea searching for moving vessels, ships, submarines etc. We flew in Blackburn Botha aircraft with pilots of all nationalities who hated the job they were doing and we were treated to much nonsense on the flights as they relieved their boredom by low flying etc. However I gained some navigation skills which eventually helped me in the job.

Near the end of this course a representative of No.1 PRU came and spoke to us and gave us a rundown on the unit operation and said they were seeking twin engine pilots to join their unit. They operated with spitfires but expected to eventually obtain a flight of twin engine mosquito aircraft. If we volunteered one could do a conversion to spitfires and later transfer back to a mosquito when they became available. I really wanted to fly a mosquito.

I volunteered and my N.Z. mate Andy Anderson didn't, he did however survive the war flying with coastal command.

It so happened that PRU never obtained mosquitoes and went through the war flying mainly spitfires. I commenced my retraining on single engine aircraft in Feb 1942 in a Miles Master and I had not flown as a pilot for about 7 months. After about 6 hours dual and 6 hours solo in the Miles they sent me off solo in a spitfire, as there were no dual seat spitfires in those days.

Spitfires

I can still remember the thrill of that first takeoff, the terrific increase in power after the Avro Anson and because of the narrow undercarriage take off and landing was a bit difficult but once in the air the plane handled beautifully. I was still at Squires Gate near Blackpool and there were several different units using the aerodrome. There was also a factory building Wellington bombers, so there were always numerous planes in the circuit. I finished at Squires Gate with 18 hours flying in Spitfires on 21st March 1942. Then I went for a week's Blind flying school to learn to fly in cloud, then on to Detling where I did 20 hours high altitude flying and practicing with the camera.

These cameras were electrically heated for the high altitudes and usually fixed behind the pilot and protruded slightly below the fuselage. They were electrically operated by the pilot and carried magazines of 350/500 prints. The photograph covered up to 7 miles on the ground depending on the height which was usually between 20000 and 30000 feet. The pilot positioned the plane directly above the target and flew steadily ahead with the camera turned on. The film operated so that each print had a 70 % overlap so that there were 2 prints of any object on the ground. I was well trained in navigation and finding targets with the camera, but no idea of ways of escape if chased by an enemy fighter. I feel that I was sent on operations at a disadvantage to fighter trained pilots. One had to hope that we saw the enemy in plenty of time to leave the area.

I joined "D" flight PRU at Benson and was authorised to take off and familiarise myself with the surrounds. Benson was a grass aerodrome with a sloping surface and I was given no direction as to parts of the drome that were a bit rough. On landing I hit a bump and wiped off the undercarriage and propeller. The flight commander commented "that was the worst bloody landing I have ever seen". Yet the next day they dragged out a brand new spitfire and from then on I was ok. I found sections of the drome that I avoided. No big deal in those days, it was just accepted.

We then moved to Mount Farm aerodrome while Benson was upgraded. It had paved strips. The ground staff had accommodation but not the pilots who travelled daily from Benson. This was a nuisance as one usually had an early take off so you usually had a cup of tea and then breakfast when returning at 10 am. I was the only non commissioned officer and the only Australian at Benson so I lived with the English ground staff, this would have been sorted after a few months as I had applied for a commission, but I did not last that long. I got on very well with all the other pilots' and mixed with them away from the aerodrome. My new commander at "F" flight suggested I apply for an officer rank.

Most of the flights were to marshalling yards on France and Belgium, Bruges, Oostende, Abbeville, St Malo, Calais, Boulogne, Charleroi, Bonn and Brussels. It was obvious this was in preparation for the raid on Dunkirk which turned out to be a failure and resulted in the loss of a whole Canadian division. When I later went to Stalag 8b there were dozens of Canadian prisoners who had been marched from France to Poland. I also did a few longer flights to Manheim, Bremerhaven, Cologne, and on June 3rd my longest flight of 5:15 to photograph a German battleship hiding in the Kiel Canal. We considered 5 hours to be the limit of the spitfire endurance.

"For you the war is over" I had completed 19 operational flights and had only seen enemy planes once before when on the way back from Cologne over Belgium I saw 5 x FW 190 fighters at about the same height and at some distance south from me, I immediately headed out over the north sea and they must not have seen me, so I was not followed. I had only one other incident where the flaps and brakes failed due to an Erk's mistake and it resulted in a high speed ground loop and some damage to my spitfire. No big deal, drag another one out the next day.

I had completed 19 operational flights and had only seen enemy planes once before when on the way back from Cologne over Belgium I saw 5 x FW 190 fighters at about the same height and at some distance south from me, I immediately headed out over the north sea and they must not have seen me, so I was not followed. I had only one other incident where the flaps and brakes failed due to an Erk's mistake and it resulted in a high speed ground loop and some damage to my spitfire. No big deal, drag another one out the next day.

On the 17th August I was sent to photograph the Bremen to Bremerhaven canal which ran for about 20 miles and was the base for the submarine fleet. I had been there previously on an unsuccessful mission due fog and on this occasion decided to commence form the Bremen end as I would be heading for the north sea on an escape route. It was about midday with no loud, and I was at 28000 feet and I was fired at from the ground but the flak bursts were not close and as I turned on my camera and started the run, in my rear vision mirror appeared a Me109.

I had no guns and no training in fighter tactics I guessed "one is up the creek without a paddle". I made an evasive move so his burst did not hit the cockpit but he hit one wing leaving one aileron flapping in the slipstream. I was still able to hold the plane level. Eventually he fired again and the burst strafed the cockpit and caused me a lot of shrapnel injury, the destruction of my instruments and I could smell petrol. I left the U.K. with 80 gallons in the main tanks and 65 gallons approx in each of the two tanks built in to the wings, the fact that it did not catch fire was amazing.

I then decided I had to bail out before being shot or burnt to death in an explosion. I remembered my escape drill although I had never jumped before - undo the harness straps, turn the aeroplane upside down as there were no ejection seats, and fall out, as well as a final kick forward to the stick to help my exit.

As I floated down my adversary circled me, and I can remember wondering if he would shoot. He apparently decided I would be caught very easily. I landed in a potato field and noticed on my way down that army trucks were speeding towards me with armed soldiers on hand very quickly. I remember feeling that I had failed and was very downhearted as I loved flying. I now have a book written about PRU which claims that in 1942 the survival rate for pilots in PRU was considered to be 30%.

I was taken to an airfield where I was well treated and shook hands with the pilot who shot me down. I was taken to the point where the plane hit the ground. It was in very small pieces and the engine was buried deep in a hole in the ground and that was the end of Spitfire BP887. My Army captors seemed to think that I had bailed out with my observer still in the plane, but of course the Luftwaffe knew that we flew reconnaissance alone. I have little recollection of my time there except that the pilot who shot me down told me he had been flying on the Russian front and that the Nazi's at that time were winning.

Mr Wright's Log Book - 'failed to return' written.

I was taken to a camp in Frankfurt called Dulag Luft. My memories of this place are vague except that I can remember being asked questions by interrogators who claimed they had lived in Australia, Canada and the U.K. Because I was flying a sky blue spitfire they knew I came from PRU and they knew the names of my commanding officers. My eventual internment in Stalag 8B with 83 other Australian airmen is well documented in a book "The RAAF POWS of Lamsdorf" but I was eventually moved from Lamsdorf to the officer's only camp - Luft III centre at Sagan and enjoyed better facilities than described in the aforementioned book. I was the only NCO at the camp due to an administration mix up.

I was moved again to Luft III Bellaria and on to Stalag VIII-B Luckenwalde. I knew the US forces were in Elbe so I joined up with them on VE day.

Paraphrasing the book "Allied photo Reconnaissance of WW2" by Chris Staerck — Not all of the many hundreds of PR missions met with success. By November 1942 the chances of a pilot surviving an operational tour with a PR squadron in NW Europe were estimated at no more than 31%. It took a particular type of bravery to fly alone, unarmed, untrained in evasive tactics and over enemy territory to bring back photographic evidence.

I believe Ken is too self effacing and humble to make any claim like this, and yet Lofty Wright completely reflects and deserves the honour bestowed in this statement!

Written by Lofty and compiled by Brad Fisher 70 years to the day after Ken took to the skies on the 6th of February 1941

The Spitfire Association

Mr Wright's Prisoner of War number was 26870 - an indication of how many men were captured and imprisoned. Luft III, where he was forst placed, is the POW Camp from which a few 'Great Escapes' occurred - see below.

Mr Wright's Prisoner of War number was 26870 - an indication of how many men were captured and imprisoned. Luft III, where he was forst placed, is the POW Camp from which a few 'Great Escapes' occurred - see below.

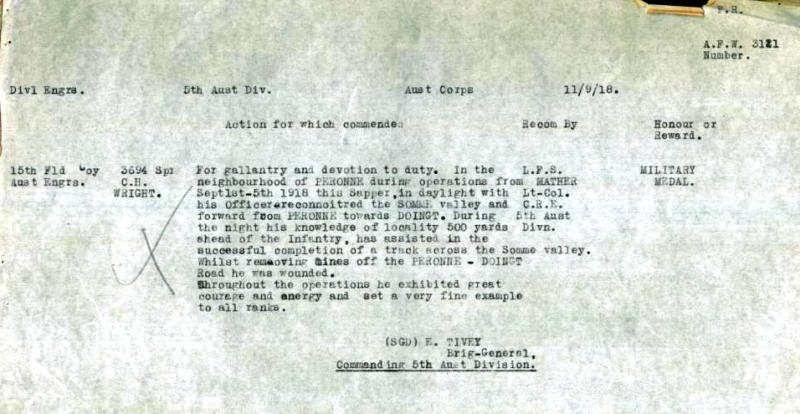

When Ken returned he went home to Lismore and returned to working at the Bank of NSW. There he met wife Lola in 1949. They married in 1950 and have two children, Barbara and Peter, two grandchildren and a great grandchild due any day now. Ken, whose father Charles served in WWI, was awarded the Military Medal

Kenneth Lindsay Wright has been awarded 1939-45 Star, Aircrew Europe Star, War Medal 1939- 45, Australia Service Medal 1939-45. Returned from Active Service Badge. Mr Wright is also a member of the Caterpillar Club – save your life parachute.

As a Manager for the Bank of NSW he was frequently moved throughout his career and recalled walking down the street in Mildura one day when the then Member for Mildura (who had been in the same P.O.W. Camp as Ken) tapped him on the shoulder. This was the beginning of deciding to have annual reunions with the 84 Australians they had been imprisoned with, at many places all over Australia during the intervening decades. Jim Henry, who only passed away three months ago, and lived at Coogee, was the closest to Ken and they would talk regularly about their experiences.

In 1972 he and Lola moved to Avalon and bought a house whee he was Manager for six years prior to retiring. Lola remained active as well, working as a Secretary for Red Cross or other such community organisations at each move and as a Medical receptionist while in Avalon – they are both still sharp minded and upright, in body and mind.

Coloued photo in Text taken at VP Day Commemorative Service, 2013 by M Mannington.

SP 888 - found by a Qantas pilot and given to Ken a few years ago - the serial number just after his Spitfire.

Kenneth Wright, 2013. AJG PIcture.

Extras:

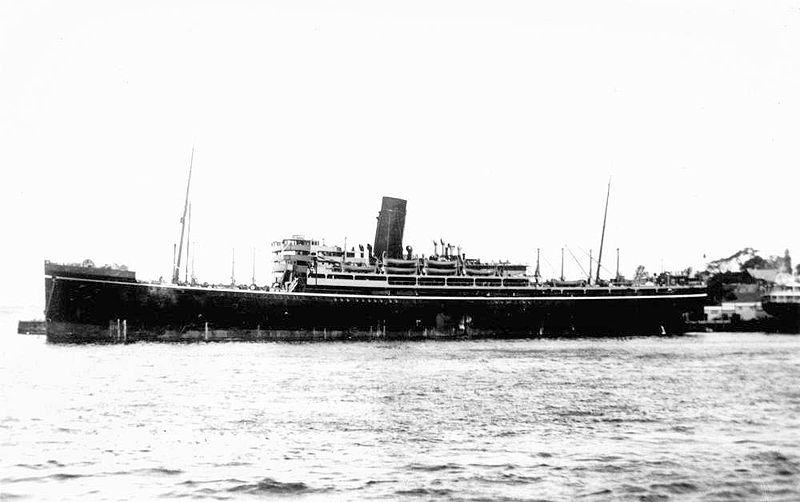

SS Awatea

In August 1936 the Union Steam Ship Co. took delivery of its new trans-Tasman liner, Awatea, which in September began a new express service. She was built to the company's design by Vickers-Armstrong at Barrow-in-Furness and was a handsome vessel with a high standard of accommodation. With a length of 527 ft, a beam of 74 ft, and a gross tonnage of 13,482, she carried 540 passengers and 342 crew and could better 23 knots. Her speed, comfort, and ability to keep going with the minimum of time in port, together with the publicity sense of her master, Captain A. H. Davey, made her a popular and well-known ship. In the summer of 1937 she made 11 Tasman crossings in 41 days and in the same year she brought the times for the Auckland-Sydney and Sydney-Wellington passages to less than 56 hours. Her best day's run was 576 miles, an average speed of 23.35 knots.

At the outbreak of war she was undergoing her annual survey and was fitted with a 4 in. gun aft. She continued to cross the Tasman until July 1940 after which she made several trips to Vancouver and, in addition, was used for transporting troops and refugees. In September 1941 she was requisitioned by the British Government for use as a troop transport and did three voyages. Then she was fitted out to take part in Operation Torch, the Allied landings in North Africa. She carried the 6th Commando group to off Algiers where she dropped them early on 8 November 1942. Eventually the Awatea anchored off Bougie, but as she was leaving German bombers attacked her and despite good anti-aircraft fire she was hit several times and sank during the night. The master, Captain G. B. Morgan, was awarded the D.S.O. and several of the crew were decorated for the ship's part in the operation.

During her six years of life the Awatea steamed 576,132 miles, slightly more than half in peacetime, including 225 Tasman crossings. In its day the Awatea provided the acme of maritime speed and comfort.

by James Oakley Wilson, D.S.C., M.COM., A.L.A., Chief Librarian, General Assembly Library, Wellington.

.jpg?timestamp=1383855535203)

Troopship Awatea goes down fighting

The Union Steam Ship Company’s sleek 13,482-ton trans-Tasman liner Awatea, launched in 1936, was one of the finest and fastest ships of its size in the world at the outbreak of the Second World War. Like many merchant vessels, the liner – and its civilian Merchant Navy crew – was pressed into wartime service.

Painted grey and fitted with defensive guns and anti-mine paravanes, the Awatea delivered New Zealand and Australian air trainees to Canada, shipped 2000 Canadian troops to Hong Kong, evacuated civilians from the Philippines and Singapore, and carried several thousand Free Polish troops from India to South Africa. During these missions the ship narrowly escaped a German U-boat attack in the North Atlantic and was involved in three collisions with other vessels. It also suffered a smallpox outbreak that killed two crew members.

On 8 November 1942 the Awatea took part in Operation Torch, the successful Allied invasion of Vichy-French North Africa. After landing 3000 commandos near Algiers, it ferried other troops further to the east. On the night of 11 November, off Bougie (Bejaia), the Awatea was attacked by swarms of German and Italian bombers. Although its gunners shot down several planes, the Awatea was set on fire and holed by torpedoes. Remarkably, everyone on board got off safely (except for the ship’s cat, which was apparently killed by a bomb blast). It was a sad end for a ship often described as the finest ever to fly the New Zealand flag.

SS Rimutaka

The SS Mongolia was a steam turbine-driven twin-screw passenger-and-cargo ocean liner launched in 1922 for the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company (P&O) for service from the United Kingdom to Australia. Later in P&O service it sailed for New Zealand, and in 1938 it was chartered to a P&O subsidiary, the New Zealand Shipping Company, who renamed her SS Rimutaka, the third ship of that name, registered at Plymouth. She was reconfigured at this time to carry 840 tourist class passengers; before entering service, she was in collision with SS Corfleet off the Nore. After repairs, she departed for New Zealand for the first time on 12 December 1938. The Rimutaka worked a route from London, through Panama, to Auckland, New Zealand and terminating at Wellington, New Zealand.

She suffered a fire in her No. 3 hold on 9 March 1939. In September of that year, she was requisitioned for conversion to an armed merchant cruiser due to the outbreak of World War II, but was released from that service before any conversion occurred. Instead, the Rimutaka was requisitioned for the Liner Division between 12 May 1940 and 14 June 1946, but remained in UK—New Zealand service for most of the war.

After hostilities ceased, she continued in NZSC service on the same route; her last voyage with the company was in 1950, departing Wellington for London in January, 1950. She was returned to parent P&O for sale. In 1950 it was sold to become the SS Europa, carrying immigrants to the United States from Europe; later, it became a Bahamas cruise ship, the SS Nassau. Its final incarnation was under a Mexican flag as a Los Angeles to Acapulco cruise liner, the SS Acapulco, making it the only ocean liner to ever fly the Mexican flag. The ship was scrapped in 1963

SS Mongolia (1922). (2013, June 5). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=SS_Mongolia_(1922)&oldid=558389987

WRIGHT, Kenneth Lindsay - (Warrant Officer); Service Number - 403176; File type - Casualty - Repatriation; Aircraft - Spitfire BP887; Place - Italy; Date - 10 August 1942

Charles Herbert Wright a carpenter prior to enlisting in the A.I.F., was attached to the 15th Field Company Engineers, part of the 15th Brigade. He sustained a chest wound on 7/9/1918 and ended up in Bristol General Hospital where he stayed until release on 20/1/1919. He returned home in March 1919.

The 15th Brigade was originally raised during World War I under the command of Brigadier General Harold Elliott as part of the expansion of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) that was undertaken in 1916 following the conclusion of the Gallipoli campaign. Drawing a cadre of experienced personnel who had fought during the Gallipoli campaign from the 2nd Brigade, the brigade was assigned to the 5th Division upon formation and was made up of four infantry battalions—the 57th,58th, 59th and 60th Battalions. Meanwhile, after July 1916 it also consisted of the following supporting elements: 15th Field Company Engineers, 15th Machine Gun Company, 15th Light Trench Mortar Battery and the 15th Field Ambulance. Following the 5th Division's arrival in Europe, the brigade's first major action came at Fromelles in July 1916 when they were committed to attacking the German positions along the Laies River which were held by the 16th Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment along with the British 184th Infantry Brigade. During the battle, two of the brigade's battalions—the 59th and 60th—were committed to the assault while the other two were held back in reserve. Of the two assault battalions, the 60th suffered the heaviest casualties, losing 16 officers and 741 men, while the 59th suffered 695 casualties.

For the next two and a half years the brigade saw service in the trenches along the Western Front in France and Flanders, taking part in actions at Bullecourt, Polygon Wood, Villers–Bretonneux and along the St Quentin Canal. Their final engagement came around Beaurevoir in late September and into early October 1918 when the Australians undertook operations to penetrate the German defences along the Hindenburg Line. During these attacks, the brigade lost 32 officers and 489 men killed or wounded.

Severely depleted and suffering from manpower shortages that was the result of the combined effect of a decrease in the number of volunteers arriving from Australia and the decision to grant home leave to men who had served for over four years, the Australian Corps was subsequently withdrawn from the line for rest on 5 October, upon a request from the Australian prime minister, Billy Hughes. When the Armistice came into effect on 11 November 1918, the Australians had not returned to the front and were still in the rear reorganising and training. With the end of hostilities, the demobilisation process began and men were slowly repatriated back to Australia. Eventually a number of the brigade's subordinate units were amalgamated, before ultimately being disbanded. On 26 March 1919, the final entry was made in the brigade's War Diary and the 15th Brigade was disbanded.

15th Brigade (Australia). (2013, March 20). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=15th_Brigade_(Australia)&oldid=545766215

The Royal Air Force has been active in Canada throughout the history of military aviation, though mainly in a supportive or advisory capacity initially. The Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Naval Air Service, forerunners of the Royal Air Force, made administrative and instructional personnel available at training establishments in Canada. Many young Canadians served in these units during WORLD WAR I and before the establishment of the Royal Canadian Air Force in 1924.

As a result of this experience in organization and co-operation, it was logical to consider Canada as the training ground for the BRITISH COMMONWEALTH AIR TRAINING PLAN(BCATP) when it was established in 1939. This agreement was signed by Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and New Zealand, on December 17, 1939, and the first schools were opened April 29, 1940. Growth thereafter was rapid, and by the end of 1943 there were 97 schools and 187 ancillary units operating at 231 sites. This number includes 27 RAF schools, seven of which were located in Saskatchewan. The choice of sites for these facilities was often controversial and more often than not politically motivated. However, it was obviously of considerable interest to a local community to be included in the list of successful candidates. The immediate economic benefits breathed new life into sections of the country still suffering from a long period of drought and depression, and in many cases this boost to the local economy resulted in the growth of new industries and services which lasted far beyond the period of wartime activity.

The students trained at these schools were predominantly RAF; but as the following numbers indicate, some were from other partners in the plan (see Table RAF-1). Students from EFTS continued their training at SFTS so that these figures do not indicate the total number of pilots produced by the BCATP; nor do they indicate the total involvement of RAF personnel trained at RCAF schools, including Bombing and Gunnery as well as Air Observer schools. Such schools—at Regina, Saskatoon, Mossbank, Dafoe, PRINCE ALBERT, Yorkton, and Davidson—trained a total of 24,775 students, of which approximately 4,500 were RAF, 1,500 RNZAF, and 2,500 RAAF. In addition to the obvious importance and success of this program, the impact on society in general should not be overlooked. Cultural influences were noticeable, and the warmth and hospitality of the host communities resulted in lasting friendships and in many cases marriages, which in turn led to resettlement for one or the other of the partners.

The British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP; "The Plan"), known in some countries as the Empire Air Training Scheme (EATS), was a massive, joint military aircrew training program created by the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, during the Second World War. BCATP/EATS remains as one of the single largest aviation training programs in history and was responsible for training nearly half the pilots, navigators, bomb aimers, air gunners, wireless operators and flight engineers who served with the Royal Air Force(RAF), Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) and Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF) during the war.

Australia

Prior to the inception of the Empire Air Training Scheme (as it was commonly known in Australia), the RAAF trained only about 50 pilots per year. Under the Air Training Agreement, Australia undertook to provide 28,000 aircrew over three years, representing 36% of the total number trained by the BCATP. By 1945, more than 37,500 Australian aircrew had been trained in Australia; a majority of these, over 27,300, had also graduated from schools in Australia.

During 1940, Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) schools were established across Australia to support EATS in Initial Training, Elementary Flying Training, Service Flying Training, Air Navigation, Air Observer, Bombing and Gunnery and Wireless Air Gunnery. The first flying course started on 29 April 1940. Keith Chisholm (who later became an ace and served with No. 452 Squadron RAAF over Europe and the Pacific) was the first Australian to be trained under EATS.

For a period, most RAAF aircrews received advanced training in Canada. During mid-1940, however, some RAAF trainees began to receive advanced training at RAF facilities in Southern Rhodesia.

On 14 November 1940, the first contingent to graduate from advanced training in Canada embarked for the UK. In January 1942, Clive Caldwell – the highest-scoring Australian ace of the war – became the first BCATP/EATS graduate to command a RAF squadron (112 Sqn).

Following the outbreak of the Pacific War, a majority of RAAF aircrews completed their training in Australia and served with RAAF units in the South West Pacific Theatre. In addition, an increasing number of Australian personnel were transferred from Europe and the Mediterranean to RAF squadrons in the South East Asian Theatre. Some Article XV squadrons were also transferred to RAAF or RAF formations involved in the Pacific War. Nevertheless, a significant proportion of RAAF personnel remained in Europe and RAAF Article XV squadrons continued to be formed there.

By early 1944, the flow of RAAF replacement personnel to Europe had begun to outstrip demand and – following a request by the UK government – was wound back significantly. Australian involvement was effectively terminated in October 1944, although it was not formally suspended until 31 March 1945.

British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. (2013, September 26). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=British_Commonwealth_Air_Training_Plan&oldid=574639747