February 3 - 9, 2013: Issue 96

Jellyfish of Pittwater

Last Saturday while at the Royal Motor Yacht Club- Broken Bay, at Newport, what are termed ‘blooms’ of jellyfish were sighted. Smaller ones seemed to be gathering in a cloud among boats moored along the seawalls while another kind moved as gracefully as ballerinas through the water, seemingly curious about those looking down at them or attracted to the hulls of vessels. They were beautiful, colourful but we didn’t know what kinds they were.

A little research allows us to share these visions and their classifications in the marine world. They also remind that there are other seemingly ‘jellyfish’ like marine species that gather in our waters and wahs on our shores that aren’t actually jellyfish. We’ve been collecting a record of these to share too.

Firstly a little bit about jellyfish though: Jellyfish are plankton (from the Greek word planktos, meaning to wander or drift) and are not strong swimmers, which keeps them at the mercy of the ocean currents. Blooms often form where two currents meet and if there is an onshore breeze thousands of jellyfish can be beached. Anemones, corals, jellyfishes and hydroids are collectively known as cnidarians. Cnidaria comes from the Greek word cnidos, which means stinging nettle. Cnidarians are classified into four main groups: the almost wholly sessile Anthozoa (sea anemones, corals, sea pens); swimming Scyphozoa (jellyfish); Cubozoa (box jellies); and Hydrozoa, a group that includes all freshwater cnidarians as well as many marine forms, and has both sessile members such as Hydra and colonial swimmers such as the Portuguese Man o' War. Fossil cnidarians have been found in rocks formed about 580 million years ago, and other fossils show that corals may have been present shortly before 490 million years ago and diversified a few million years later. There are over 10, 000 known species.

Most jellyfish live less than one year, and some some of the smallest may live only a few days. Each species has a natural life cycle in which the jellyfish form is only part of the life cycle The most familiar stage is the medusa stage, where the jelly usually swims around and has tentacles hanging down. Male and female medusae reproduce and form thousands of very small larvae called planulae. The larvae then settle on the bottom of the ocean on rocks and oyster shells and form a small polyp that looks just like a tiny sea anemone. Each polyp will bud off many baby jellyfish called ephyrae that grow very quickly into adult medusae. Some scientists believe that jellyfish have increased because coastal development helps provide more underwater habitat for jellyfish polyps to grow.

Those photographed in Pittwater so far:

Moon Jelly

The Moon Jelly Aurelia aurita (also called the moon jellyfish, common jellyfish, or saucer jelly) is a common ocean animal and can be extremely abundant as seen here. Currents often sweep them into sheltered bays. They live in oceans, coastal waters and estuaries. All species in the genus are closely related, and it is difficult to identify Aurelia medusae without genetic sampling; most of what follows applies equally to all species of the genus: The medusa is translucent, usually about 25–40 cm in diameter, and can be recognized by its four horseshoe-shaped gonads, easily seen through the top of the bell. It feeds by collecting medusae, plankton and mollusks with its tentacles, and bringing them into its body for digestion. It is capable of only limited motion, and drifts with the current, even when swimming.

They feed on plankton that includes organisms such as mollusks, crustaceans, tunicate larva, rotifers, young polychaetes, protozoans, diatoms, eggs, fish eggs, and other small organisms. Both the adult medusae and larvae of Aurelia have nematocysts to capture prey and also to protect themselves from predators. The food is caught with its nematocyst-laden tentacles, tied with mucus, brought to the gastrovascular cavity, and passed into the cavity by ciliated action. There digestive enzymes from serous cell break down the food. There is little known about the requirements for particular vitamins and minerals, but due to the presence of some digestive enzymes, we can deduce in general that A. aurita can process carbohydrates, proteins and lipids. Aurelia does not have respiratory parts such as gills, lungs, or trachea. Since it is a small organism, it respires by diffusing oxygen from water through the thin membrane covering its body. Within the gastrovascular cavity, low oxygenated water can be expelled and high oxygenated water can come in by ciliated action, thus increasing the diffusion of oxygen through cell. The large surface area membrane to volume ratio helps Aurelia to diffuse more oxygen and nutrients into the cells. They are a favourite food of many species of turtle, particularly the Leathery Turtle which has been recorded in Cowan Creek. If you look at the appearance of these jellyfish you can understand why turtles will eat plastic bags of they are discarded into waterways as they often mistake them for one of the species on their menu. (1)

Bluebottles

The Portuguese Man O' War Physalia physalis, also known as the Portuguese Man-Of-War, Man-Of-War, or Bluebottle, is a jellyfish-like marine cnidarian of the familyPhysaliidae. Its venomous tentacles can deliver a powerful sting. The name "man o' war" comes from the man-of-war, a 16th-century armed sailing ship, and the cnidarian's supposed resemblance to the Portuguese version at full sail. This species and the smaller Indo-Pacific man o' war are responsible for around 10,000 human stings in Australia each summer, particularly on the east coast. The Portuguese man o' war is a carnivore which uses its venomous tentacles, a man o' war traps and paralyzes its prey. Typically, men o' war feed upon small aquatic organisms, such as fish and plankton. They form a part of the loggerhead turtles diet.

The best treatment for a Portuguese man o' war sting is:

To avoid any further contact with the Portuguese man o' war and to carefully remove any remnants of the organism from the skin (taking care not to touch them directly with fingers or any other part of the skin to avoid secondary stinging); then

To apply salt water to the affected area (not fresh water, which tends to make the affected area worse)

To follow up with the application of hot water (45 °C/113 °F) to the affected area from anywhere between 15-20 minutes which eases the pain of a sting by denaturing the toxins.

If eyes have been affected, to irrigate with copious amounts of room-temperature tap water for at least 15 minutes, and if vision blurs or the eyes continue to tear, hurt, swell, or show light sensitivity after irrigating, or there is any concern, to see a doctor as soon as possible.

Vinegar is not recommended for treating stings. Vinegar dousing increases toxin delivery and worsens symptoms of stings from the nematocysts of this species. Vinegar has also been confirmed to provoke haemorrhaging when used on the less severe stings of nematocysts of smaller species. (4.)

Jelly Blubber Blubber Jellyfish Catostylus mosaicus, also known as Jelly Blubber. Found in intertidal estuaries and coastal waters of eastern Australia they are the most commonly encountered jellyfish with large swarms appearing in estuaries. In Sydney waters, the Jelly Blubber's large bell is a creamy white or brown colour, but farther north it is usually blue. This is because the jellyfish has developed a symbiotic relationship with algal plant cells that are kept inside its body. These plants vary in colour from region to region. The algae photosynthesise, converting sunlight into energy that can be used by the jellyfish. The Jelly Blubber has no mouth but there are many tiny openings in its tentacles. The tentacles also have stinging cells that can capture tiny crustaceans and other plankton. (2.)

Blubber Jellyfish Catostylus mosaicus, also known as Jelly Blubber. Found in intertidal estuaries and coastal waters of eastern Australia they are the most commonly encountered jellyfish with large swarms appearing in estuaries. In Sydney waters, the Jelly Blubber's large bell is a creamy white or brown colour, but farther north it is usually blue. This is because the jellyfish has developed a symbiotic relationship with algal plant cells that are kept inside its body. These plants vary in colour from region to region. The algae photosynthesise, converting sunlight into energy that can be used by the jellyfish. The Jelly Blubber has no mouth but there are many tiny openings in its tentacles. The tentacles also have stinging cells that can capture tiny crustaceans and other plankton. (2.)

Marine species that look like but are not Jellyfish

These half arc crescent- jelly like objects are actually the egg sacs of Sand Snails. There are a few species of Sand Snails common in our area. The Conical Sand Snail (Polinices conicus) is a honey-coloured, pear-shaped shell with a brown or orange band along the top of each whorl. It grows to 42mm and is found on sand flats of sheltered beaches and estuaries. Polinices incei grows to about the same size but varies in colour and is rounder. The Sordid or Leaden Sand Snail (Polinices sordidus) prefers the more muddy conditions of estuaries. Its shell, which grows to about 36mm, varies from grey to brown with an orange outer lip. (3.) Sand snails lay their eggs in these kidney-shaped egg jellies, sometimes called ‘horseshoe jellies’. If you hold them up to the light you will see spots inside which are the tiny eggs. This one was photographed on the mudflats of Careel Bay in 2009.

These half arc crescent- jelly like objects are actually the egg sacs of Sand Snails. There are a few species of Sand Snails common in our area. The Conical Sand Snail (Polinices conicus) is a honey-coloured, pear-shaped shell with a brown or orange band along the top of each whorl. It grows to 42mm and is found on sand flats of sheltered beaches and estuaries. Polinices incei grows to about the same size but varies in colour and is rounder. The Sordid or Leaden Sand Snail (Polinices sordidus) prefers the more muddy conditions of estuaries. Its shell, which grows to about 36mm, varies from grey to brown with an orange outer lip. (3.) Sand snails lay their eggs in these kidney-shaped egg jellies, sometimes called ‘horseshoe jellies’. If you hold them up to the light you will see spots inside which are the tiny eggs. This one was photographed on the mudflats of Careel Bay in 2009.

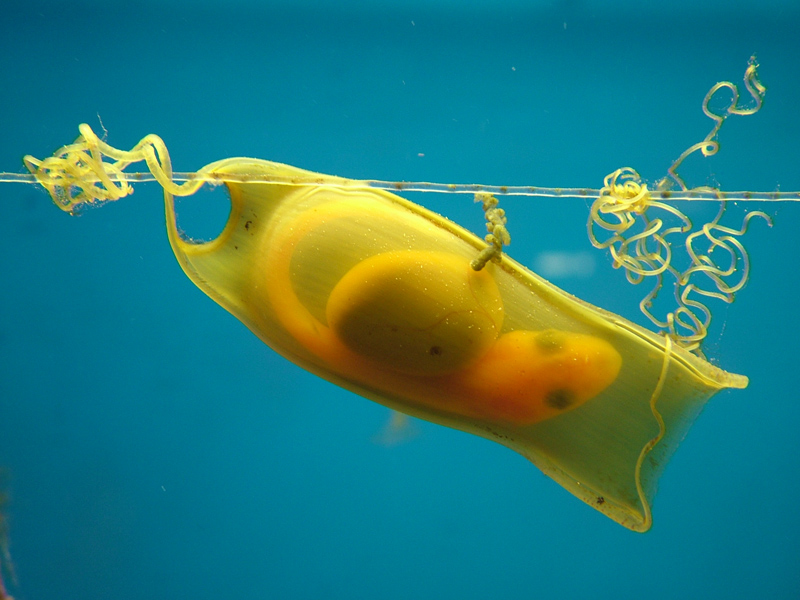

The other marine object you may find washed up on the estuary beaches or ocean shores are shark egg sacs. If seen in the water they are still semi-translucent. Some species are oviparous like most other fish, laying their eggs in the water. In most oviparous shark species, an egg case with the consistency of leather protects the developing embryo(s). These cases may be corkscrewed into crevices for protection, giving them their 'screw' appearance. Once empty, the egg case is known as a mermaid's purse, and can wash up on shore. Oviparous sharks include the horn shark, catshark, Port Jackson shark, and swellshark. (5)

The one shown here was found adjacent to Station Beach, Palm Beach on Thursday, perhaps discarded by someone who decided against taking the smell home.

Although these marine creatures and offcasts from new marine creatures are beautiful, advising our younger generation not to step on them with bare feet or handle them will ensure they don’t get stung. Bluebottles do still sting those who jog over them while still wet, even hours after being washed onto the sand, and most jellyfish, if they can sting their prey, can sting you too.

References:

1.Aurelia aurita. (2013, February 1). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Aurelia_aurita&oldid=536064831

2.Australian Museum.

3.Jenny Edwards. Murder Mysteries. Nature Coast Marine Group Inc. (NCMG) - 20 July 2004.

4.Portuguese man o' war. (2013, February 2). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Portuguese_man_o%27_war&oldid=536116587

5. Shark. (2013, February 1). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Shark&oldid=535997429

Photo of Shark egg with shark still in it: ‘New life’ by and courtesy of Boeddha, March, 2009.

How a Jellyfish swims - Chrysaora quinquecirrha ("sea nettle") swimming by Kuma 1024; taken at Ocean Park Hong Kong.

Report and Pictures by A J Guesdon, 2013.